Abstract

Student engagement is a prerequisite for successful learning. Due to the tremendous change in the use of information and communication technologies, the nature of this engagement has had to adapt to fit a hybrid approach of teaching and learning. In this qualitative study, three focus group discussions were conducted that aimed to investigate adult learners’ perspectives on their engagement in a hybrid learning postgraduate programme. Deductive content analysis was done of the transcribed data using Pittaway’s Engagement Framework. Main findings were that adult learners’ computer literacy skills impacted on their own self-efficacy towards their ability to study and use technology. Lecturers’ social engagement, especially their support to students, was also highlighted. Other factors, such as Internet access and power failures, hampered adult learners’ access to online activities. An adapted engagement framework for adult learners is proposed and should be taken into account when developing new online programmes for adult learners.

Introduction and Background to the Study

The past 20 years show a tremendous development of information and communication technologies globally (Meydanlioglu & Arikan, Citation2014). As a result, institutions of higher learning have been challenged to invest in the use of computer and Web technologies as an alternative way to enhance student engagement and facilitate effective learning (Tomas, Lasen, Field, & Skamp, Citation2015; Waha & Davis, Citation2014). This changed the worldwide way of teaching in higher education from a traditional face-to-face model to a hybrid approach. In a hybrid approach, online components are integrated with face-to-face learning to suit the changing needs of the students who assume or prefer the presence of online learning as part of their engagement with their studies (Jefferies & Hyde, Citation2010). Since student engagement is documented as a prerequisite for effective learning (Baker & Pittaway, Citation2012; Krause, Citation2005), this change is not to be taken lightly. It is against the background of this changed environment that this study was conducted—to gain a better understanding of a particular group of adult learners’ engagement experiences with the long-term aim of improved curriculum design and development.

The University of Pretoria offers part-time courses to adult students (above 21 years upon entering higher education) who are employed full-time. These students have scheduled face-to-face sessions augmented by online-based learning. The online educational environment affords learners the chance to continue with their learning activities when they return home and to their working environments. However, this online environment with its affordances poses additional challenges where the use of technology is regarded as a basic part of learning for current school leavers (Jefferies & Hyde, Citation2010). Adult learners who are more mature may not have prior exposure to technology for online learning, where the younger students might (Tomas et al., Citation2015). Research also found that adult learners were often employed and may have family responsibilities (Tomas et al., Citation2015) in addition to their studies, adding further stress to their lives. The result is less time to attend to their studies and the additional challenges of figuring out how the technology works.

A hybrid model for curriculum design and delivery was accepted by the council of the University of Pretoria (UP) in South Africa in 2014. One of the hybrid learning postgraduate programmes offered by UP does not require students to be on campus. Before the hybrid approach was implemented in 2014, students received one week of face-to-face on-site teaching and were required to engage in the learning material independently. The fact that students are dispersed all over South Africa and outside the country’s borders, as well as the fact that they are employed full-time, makes more face-to-face teaching opportunities challenging due to the extra financial costs students have to incur to travel and stay in Pretoria for the duration of the on-site week.

Since 2014, a revised curriculum was implemented for the specific postgraduate programme, which expected active student participation in clickUP (the brand name of UP’s online course management system). The introduction of a course presence in clickUP, as well as continuous formative assessment (through students completing several online quizzes) and regular feedback assisted to scaffold student learning. Frequent engagement with online activities encourages students to stay current with each module. This new approach to online engagement motivated students to read and engage extensively with the learning material, resulting in students being better prepared for their assignments, also submitted via the course management system (clickUP).

Students enrolled in the specific postgraduate programme are from various provinces in the country with some residing in remote rural areas. Online learning therefore seems ideal for them. However, for those students who have not necessarily been exposed to technology previously, the online learning environment does pose several challenges that should be considered. This article therefore focuses on the question of how a particular group of adult learners perceive their engagement within a hybrid learning model in a postgraduate programme in South Africa.

For clarity, terms used in this article, such as course management systems, adult learner, and engagement framework, are explained.

Course Management Systems

Due to the urge to use technology at higher institutional levels, universities increasingly began to implement course management systems (e.g., Blackboard, Learning Space, Vula, and Desire2Learn), which are software systems specifically designed and marketed to be used by lecturers and students in teaching and learning (Malikowski, Thompson, & Theis, Citation2007; Morgan, Citation2003; Unwin et al., Citation2010). Lecturers use such systems to ensure quality in the process of designing and delivering online learning and to give more attention to aspects such as curriculum and content organisation, communication, teaching, support strategies, assessment, and resources that stimulate student engagement and learning (Brinthaupt, Fisher, Gardner, Raffo, & Woodard, Citation2011), as well as to achieve teaching goals, such as increased transparency and feedback, supplementing lecture materials, and increased contact with and between students (Morgan, Citation2003).

Adult Learners

The context of adult learners—not only their working context but also the personal environment—influences the way they engage in their studies (Merriam, Citation2004; Citation2008), For example, in a study conducted in the United Kingdom (Jefferies & Hyde, Citation2010), adult learners, who had to cope with employment and family responsibilities in addition to their studies, indicated that they enjoyed the “freedom” of the online teaching environment by engaging in their studies during times that suited them best. Some diligently worked during the evenings while others preferred to work on weekends (Jefferies & Hyde, Citation2010).

It is therefore important to gain insight into the particular social, cultural, personal, and economic forces that shape adult learners’ learning environments to understand the needs and requirements for their engagement regarded as a key entry point into higher education (Stone, Citation2012). The Engagement Framework as proposed by Pittaway (Citation2012) provides a comprehensive understanding of adult learners’ engagement.

The Engagement Framework

Barkley (Citation2010, p. 8) defines student engagement as “the process and … product that is experienced on a continuum and results from the synergistic interaction between motivation and active learning.” Although student engagement is documented as a prerequisite for effective learning (Baker & Pittaway, Citation2012; Krause, Citation2005), the challenge is to support and effectively engage with such students to enable them to succeed (Stone, Citation2012).

All teaching happens within a context or environment (Pittaway, Citation2012). It is the responsibility of lecturing staff to construct the (online or on-campus) environment in such a way that students are motivated and engaged in purposeful learning activities. Lecturers impact on this environment when they make specific decisions when creating an environment that is conducive to learning. As not all lecturers teach in the same way or have the same expectations of themselves and their students, environments differ between lecturers. One important prerequisite for student engagement is that all lecturers should aim for a respectful, safe, and supportive environment in which teaching and learning can take place (Pittaway Citation2012). By itself, the environment plays a significant role in influencing each element of the Engagement Framework (Pittaway, Citation2012) and the elements cannot be separated from these environmental factors.

Key Principles

The following are the four key principles that underpin the Engagement Framework (Pittaway, Citation2012):

Staff should be engaged to enable learners to be engaged.

Respectful and supportive relationships should be developed that are vital for teaching and learning.

Learners should be provided opportunities or responsibilities for their own learning.

High standards should be set and expectations clearly communicated to enable students to develop knowledge, understanding, skills, and capacities while their learning is scaffolded.

Elements

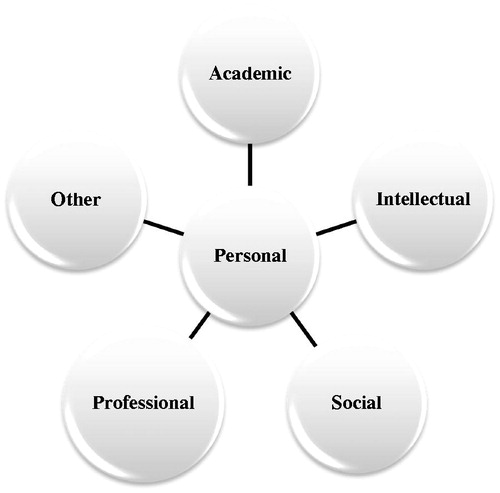

The framework consists of five elements that are fundamental to how students engage and that influence their success at university. These elements are personal, academic, intellectual, social, and professional engagement – with elements equally important and often intersecting one another (Pittaway, Citation2012; Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014). A short description of each element follows as a brief background for the focus of the current research.

Personal Engagement (Student and Lecturer)

Students have specific experiences, expectations, assumptions, skills, and knowledge and personalities that they could apply to succeed in their studies. Personal engagement includes not only students’ believing in their own abilities to succeed in their studies, but also other attributes, such as goal-setting, self-efficacy, awareness of intention, resilience, and persistence (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014). On the other hand, lecturers must similarly be personally engaged in their work with their students. Lecturers should be conscious of how their level of personal engagement affects their teaching and support of student learning and development.

Academic Engagement

Academic engagement entails the identification and management of both student and staff expectations in the formal face-to-face (classroom) environment and outside of it (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014). Students must take control of their studies through planning, monitoring, and evaluating their learning. In this process of evaluating and monitoring their progress, students will develop qualities such as computer literacy skills, academic writing skills, and referencing and note-taking skills (Baker & Pittaway, Citation2012).

Intellectual Engagement

Critical thinking and reading widely in their field enable students to intellectually engage in terms of ideas and concepts in their discipline, as well as political, ethical, and social issues within this context (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014). Intellectual engagement also highlights students’ awareness of their own values, beliefs, and attitudes regarding the disciplines to which they are exposed. Personal and academic skills are thus needed to engage intellectually.

Social Engagement (Student and Lecturer)

Social engagement allows students to extend their own beliefs and perspectives to interpret the world in different ways (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014) and a degree of maturity is needed to develop relationships. Students should be open to building relationships both face-to-face, as well as in online learning communities (Stanford-Bowers, Citation2008). Effective online teaching promotes social interaction between students, and between students and teaching staff (Edwards, Perry, & Janzen, Citation2011). Students’ level of satisfaction of their perceived learning in online courses significantly correlated to the level of students’ interaction with their lecturer and peers (Frederickson, Shea, & Pickett, Citation2000). The online environment in this study provides students who are geographically separated with the opportunity to socially engage with their peers and lecturers.

Professional Engagement

Professional engagement is specifically important for professional courses that prepare students for specific professions such as nursing or teaching (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014). This connects practice and theory and applies theoretical constructs in professional contexts, such as work-integrated learning programmes.

Student engagement is an integral part of hybrid learning environments. This, study therefore, aims at exploring a group of adult learners’ experiences on their engagement in a postgraduate hybrid learning programme, using the Engagement Framework (Pittaway, Citation2012).

Method

Research Design

This qualitative study aims to elicit participants’ accounts of meaning, experience, or perception (De Vos, Strydom, Fouché, & Delport, Citation2011). To explore students’ experiences of their participation in a hybrid learning programme, as well as how they engage in online activities, two focus group interviews were conducted in November 2015 and March 2016, respectively, with students enrolled in a specific postgraduate programme. The question posed during the focus group was “What do you perceive to be positive or negative aspects about the postgraduate programme in which you are enrolled with respect to module content, module delivery, and assessment?”

Four individual telephonic interviews were also conducted in November 2015 with students from rural parts of South Africa who could not attend a focus group at the university. For this article, the data of the individual interviews will be regarded as another focus group.

Participants

In the three focus groups, 21 of the 39 (54%) students consented to participate. The ages of the participants ranged from 24 years to 49 years (M = 35), of whom 14% were male and 86% female. Four of the 11 official South African languages, namely Afrikaans (46%), English (12%), isiZulu (24%), and isiNdebele (6%), were the first languages of the participants. One (6%) other participant was Greek and one, an international participant (6%), spoke Ikalanga (one of the languages spoken in Botswana) as her first language. The majority of participants (94%) were full-time-employed educators and 6% were speech-language pathologists. Coming from various parts of the country, 47% of the participants resided in urban (city) areas, 41% in rural (small town) areas, and 6% in undeveloped rural areas. One participant (6%) did not specify area of residence. Undeveloped rural areas refer to areas in South Africa that typically have underdeveloped infrastructure (limited electricity services and weak or no cell phone and Internet receptance) and high levels of poverty and unemployment (In-On-Africa, Citation2013).

All the participants owned mobile phones, of which 59% had smartphones. More than half of the participants (59%) owned their own computer and 100% of them had Internet access from home (although some stated that access was not necessarily reliable). Participants spend on average 7.9 hours (1–25 hours) per week online for study purposes. With regards to their own computer literacy skills, 43% of the participants (N = 21) regarded themselves as intermediate computer users (i.e., comfortable using computers and Internet); while 38% were advanced computer users (i.e., they felt they had expertise using the computer and enjoyed using it and the Internet, and exploring new programmes). Some 19% of participants did not answer the question (missing data).

Procedure

Approval was obtained from the head of department, the Registar of the University of Pretoria and the Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Humanities of the University of Pretoria before the study commenced.

All students (N = 39) received written information about the study. Only 21 (54%) provided informed written consent to participate in the study.

A focus group interview guide (Johnson, Nilsson, & Adolfsson, Citation2015) was constructed to assist the researchers to establish predetermined questions that would engage the participants to share their perceptions and experiences. The interview guide was tested as a pilot by the first author, who conducted an individual interview with one of the students to determine if the questions were understood correctly to elicit the desired answers and to request input on the question format. As part of the pilot study, three experts in the field of hybrid teaching methods also commented on the questionnaire. Minor amendments were made to the interview guide after the pilot study (e.g., prompting questions were added to the main questions). The participant from the pilot also suggested that the questions be provided in print to the participants during the focus group to make it easier to refer to them during the discussions.

The focus group interviews varied from 89 minutes to 127 minutes. The first author of the article (with experience in conducting focus groups) acted as the focus group facilitator, while the fourth author typed all the participants’ comments verbatim on a laptop. All comments were projected on the wall. The main question was divided into two main questions, and three supporting sub-questions were used. The first question was “What do you perceive to be positive aspects about the specific postgraduate programme in which you are enrolled with respect to (a) module content; (b) module delivery; and (c) module assessment?” The second question was: “What do you perceive to be problems associated with the specific postgraduate programme in which you are enrolled with respect to (a) module content; (b) module delivery, and (c) module assessment?” First, the participants received different-coloured Post-it notes to write their possible answers to the different sub-questions. The use of Post-it notes ensured that all the participants had a chance to share their opinions.

The telephonic interviews were conducted by a research assistant who has experience in conducting interviews. The lengths of the individual interviews varied from 27 minutes to 43 minutes. The same interview script used for the focus groups was used, with minor amendments to wording to suit the individual setting. The first author was present during all the telephonic interviews to ensure the interviewer followed the interview schedule, thus ensuring procedural reliability.

All statements were reviewed and revised where necessary by all participants in the focus groups. As part of member checking, participants confirmed whether the statements correctly represented their experiences (Johnson et al., Citation2015). Where necessary, more information was provided.

Data Analysis

The voice recordings of the individual interviews were transcribed verbatim by the research assistant. To improve the trustworthiness of the data, the reliability of the transcriptions was checked by the second author, who listened to all the individual interviews and recorded any disagreements of the transcriptions done by the research assistant. The 90% agreement reached between the two persons’ transcriptions was regarded as an acceptable level of reliability (Heilmann et al., Citation2008). The statements were then transferred into an Excel spreadsheet and divided into meaning units grouped according to the perspectives of the three questions: module content, module delivery, and module assessment.

Through mutual agreement, the first three authors worked together and did deductive content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005) of the data using existing theory, namely the Engagement Framework (Pittaway, Citation2012; Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014), to identify key variables as initial coding categories. The five elements were personal, academic, intellectual, social, and professional engagement. Next, each category’s operational definitions were determined using the theory (Hsieh & Shannon, Citation2005). Thereafter, the meaning units were coded using the predetermined codes. Any text that could not be classified in the initial coding scheme was allocated to “other” (e.g., external factors such as Internet, electricity, and financial challenges not directly related to engagement but which could influence student engagement).

Results

The results are presented according to the three questions posed during the focus group interviews (based on module content, module delivery, and module assessment). These sub-divisions are presented using the Engagement Framework and discussed in terms of the five elements within this framework.

shows that a total of 191 statements were recorded, of which 103 were positive and 88 negative. The data revealed statements pertaining to academic engagement (36%); other (20%); student personal engagement (15%); lecturer personal engagement (10%); and lecturer social engagement (7%). Only 5% of statements referred to professional engagement; 4% to social engagement with peers; and 3% to intellectual engagement. The results are presented on participants’ perceptions of programme content, programme delivery, and programme assessment as coded according to the different engagement categories.

Table 1. Summary of Statements per Question.

Module Content

Participants provided 16 positive and 39 negative statements when reflecting on the content of the module. Of the positive statements, seven reflected matters of professional engagement (comments related to practical implementation of the content in the workplace); four academic engagement (students’ academic search skills and computer literacy skills); two student personal engagement (students’ expectations); one lecturer personal engagement (lecturer’s skills); and two intellectual engagement (critical thinking). No statements reflected social engagement with peers or lecturers. The negative statements were 16 on personal (student’s ability and skills, knowledge, self-efficacy) and 14 on academic engagement (student’s academic searching skills; note-taking; time and planning; computer literacy skills and knowledge). Data further highlighted other factors (eight), such as Internet access, power failures due to load shedding, and financial and personal challenges. Refer to for examples of statements by participants. One negative statement was related to social engagement in that the lecturer did not support the student as expected.

Table 2. Coding Categories and Sub-Categories of Participants’ Perceptions on the Aspects of the Programme Module Content.

Module Delivery

shows that a total of 37 positive and 19 negative statements were made in relation to module delivery. Some 17 of the positive statements reflected lecturers’ personal engagement (with specific reference to their teaching skills, knowledge, and personality). Social engagement with peers was mentioned six times, whereas one statement was made on social engagement with lecturers. Five statements reflected students’ personal engagement (expectations and self-efficacy) and three each on academic (student computer literacy and planning skills) and professional engagement (implementation of content in the workplace). Two statements were on other factors such as various teaching strategies (referring to hybrid learning opportunities). No statements (either positive or negative) reflected students’ intellectual engagement. Regarding the negative statements, 10 reflected students’ academic engagement (computer literacy, planning skills, and knowledge); three student personal engagement (self-efficacy and knowledge); two lecturer social engagement; two other (Internet access); and one each on lecturer personal engagement (knowledge) and peer social engagement. provides examples of the statements made under each category.

Table 3. Coding Categories and Sub-Categories of Participants’ Perceptions on the Aspects of the Programme Module Delivery.

Module Assessment

A total of 64 statements were made on module assessment, of which 34 were positive and 30 negative (see ). The positive statements mostly reflect students’ academic engagement (computer literacy, academic searching, academic writing, planning skills, and knowledge). Next, lecturer social engagement (with specific reference to support) was mentioned nine times, followed by three intellectual engagement statements (critical thinking) and two other (electricity). Students’ academic engagement (with specific reference to computer literacy, academic writing, planning skills, and knowledge) were mentioned 18 times, while other factors (such as financial, Internet, and technical issues) were mentioned nine times. Participants did not refer to professional, social engagement with peers, and personal engagement of students and lecturers when they discussed programme assessment. Technical issues referred to challenges experienced by participants due to external problems experienced when submitting assignments through Turnitin (on the course management system). Two comments were made about student personal engagement and one about social engagement (lecturer support). Refer to for more detailed examples.

Table 4. Coding Categories and Sub-Categories of Participants’ Perceptions on the Aspects of the Programme Module Assessment.

Discussion

The discussion is presented using the components of the Engagement Framework (Pittaway Citation2012), with an additional other category. Academic engagement was highlighted by participants in the discussion of all three questions, and computer literacy skills formed an important component of participants’ discussion of this element. Most participants (62%; N = 21) regarded their computer literacy skills as either intermediate or did not comment on their computer literacy skills and therefore questioned their own abilities and skills when engaging in hybrid learning activities. They found these activities “overwhelming” and “too much” and thus suggested more training in the use of the online course management system (clickUP). Others provided possible solutions that could limit their online engagement (e.g., to receive the module content [that they should retrieve online] on a CD or in print during their face-to-face sessions). This request could also indicate some students’ lack of academic search skills as they possibly did not know how to retrieve the required reading articles online.

On the other hand, some participants experienced the hybrid learning experience as positive. They indicated that even if they lacked confidence in engaging in hybrid activities at the beginning of their studies, their confidence and competence in the use of technologies increased as they became more settled in their studies and the hybrid model of delivery. For example, one person said, “First year challenging… you get used to the system.” One participant also stated, “The use of technology is encouraging and forced us to use technology. [It was] also convenient to use technology, for example, our cell phones.”

It is the responsibility of lecturing staff to present the hybrid learning environment to motivate students to be engaged in purposeful learning activities and ensure immediate feedback (Brinthaupt et al., Citation2011). Participants acknowledged that the completion of online quizzes was a good way to assess them; to equip them to prepare better for their written assignments, and to help them study. As participants’ knowledge increased by reading more to complete the quizzes, they would have preferred to have had the option of returning to previous questions to correct mistakes. The various assessment opportunities, such as quizzes, tests during on-site weeks, and assignments, were appreciated by the participants as they realised that it helped them to obtain a better year mark: “The more assessment opportunities helped us to obtain a better year mark as with only one [opportunity].” The immediate feedback of the online assessment activities was a positive experience for the participants, who also commented on their lecturers’ comprehensive feedback on their assignments. Some participants, however, complained that they received feedback long after their assessment tasks were submitted online through the course management system.

Participants also referred to their academic planning skills when they commented on the time it took them to study, which was sometimes longer than expected; implying that they may have underestimated the level and amount of work as well as the time needed to attend to their studies. As the programme was structured and module assessment was done in a consecutive way (new modules’ online quizzes were made available once the previous module’s assignment was submitted), some students preferred all the quizzes and content to be made available at the start of the programme. In this way they can work on their studies in their own time and prepare in advance for their assignments and the exam period.

The next category that received the most statements was the other category (39%). Participants mostly complained about Internet, electricity, and financial challenges. At least 47% (N = 21) of the participants live in rural areas where cell phone and Internet reception proved to be a challenge (In-On-Africa, Citation2013). Furthermore, in South Africa, the national service provider, Eskom, was faced with the challenge that the electricity demand exceeded the available supply (Schutte, Kleingeld, & Pelzer, Citation2007). During 2014 and 2015, “load shedding” was therefore implemented according to a specific schedule for specific areas to limit electricity usage during peak hours. The load shedding also influenced these participants’ engagement with their studies, as the times when load shedding took place were typically during the evenings when they could have studied. Internet issues were also experienced due to no electricity. Financial challenges were indicated as a major problem for participants, especially those who did not reside in Gauteng province, where the University of Pretoria is located. These participants had additional financial expenditures such as having to pay extra for the opportunity to write exams near their place of residence.

Next, personal engagement of the students and lecturers was noted by the participants. With respect to the lecturers, participants commented on lecturers’ knowledge and skills to teach and support students. Personal engagement of students was highlighted the most by participants’ perception of their own self-efficacy. Perceived self-efficacy is defined as personal judgments of one’s competencies to perform and organise courses of action to achieve designated goals, and the person’s desire to assess its level, generality, and strength across activities and contexts (Bandura, Citation1977). Participants found the content demanding and difficult to grasp, and the time too short for each module, as they needed more time to comprehend the content. Zimmerman (Citation2000) has found that students’ self-efficacy beliefs about their academic capabilities impacts on their motivation to succeed academically and how they interact with their self-regulated learning processes. Developers of hybrid learning courses for adult learners should take note of the impact of students’ self-efficacy beliefs and implement support to students in this regard.

Social engagement with lecturers and peers was highlighted by participants’ comments on the comprehensive feedback and academic support they received from their lecturers. Lecturers could mostly be contacted telephonically or via e-mail. These findings may indicate that the lecturers promoted social interaction between students and teaching staff (Edwards et al., Citation2011) due to effective online teaching support. However, more specific detail on teaching by the lecturers was not mentioned by the participants.

As most participants were educators (94%), they indicated that they could successfully apply module content in their work setting (professional engagement). The knowledge that they gained was thus of practical value for them, where they could implement theory with practice (Pittaway & Moss. Citation2014).

Finally, participants commented on intellectual engagement with comments such as (the module content) “opened my mind and thinking, challenged me to think” and “it capacitated us.” This emphasises the importance of considering maximum intellectual engagement opportunities when designing hybrid learning programmes—opportunities to demonstrate critical thinking (Pittaway & Moss, Citation2014) and reflection on our own beliefs, values, and attitudes.

Conclusion

The findings of this study could have implications on both a theoretical and practical level. Theoretically, these findings are noteworthy because they provide further evidence on how adult learners perceive their engagement in a hybrid learning programme, based on the Engagement Framework (Pittaway, Citation2012). The findings also highlighted how adult learners engage in hybrid learning programmes—and what factors should be taken into consideration when planning other hybrid learning programmes for adult learners who may have intermediate to low computer literacy skills. The importance of lecturer engagement (either personally or socially), especially with adult learners during the hybrid learning activities, has been emphasised by this study. The results of this study also show how adult learners with intermediate computer literacy skills led to poor self-efficacy, which was improved once the students became more competent in their use of technology.

One element that seems to hugely influence adult learners’ online engagement experiences in a hybrid learning environment is that of the other context. This element is not part of the Pittaway (Citation2012) Engagement Framework. These were matters of finance, access, and the availability of electricity. An adapted engagement framework for adult learners is therefore proposed, with an additional element other added to Pittaway’s Engagement Framework (2012). This would emphasise adult learners’ unique needs when enrolling for online and hybrid courses and underscores the latest context-based theories on adult learning. reflects the proposed adapted engagement framework for adult learners. Developers of future hybrid learning programmes for adult learners should take these findings into account and base their programmes on the adapted engagement framework for adult learners as proposed in this study.

Limitations and Future Research

Some limitations to this study should be noted. The perceptions of only adult learners and not that of their lecturers were investigated. Due to the focus group format of data collection, it was not possible to link the data obtained from the biographical questionnaires to those of the statements made during the focus groups. If semi-structured individual interviews were done, it could have been that a clearer link to specific issues raised could have been drawn. For future research, it is suggested to include lecturers’ perceptions on how they perceive adult learners’ engagement in hybrid learning programmes. Adult learners who were part-time students from only one department and in one university in South Africa participated in this study. It may be that the demands of hybrid learning programmes at other universities in South Africa and elsewhere in the world differ from the one investigated. Therefore, it is suggested for future research to do a comparative study of two or more universities in South Africa that offer similar hybrid learning programmes to determine generalisability of outcomes of the current study. Although the participants’ level of computer literacy was intermediate to low, the statements of participants could not be linked to specific persons as the focus group methodology did not allow for it.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank the Registrar of the University of Pretoria, the Head of Department where the participants were enrolled for their approval of this study. We also thank the participants for participating in the focus groups.

Funding

The financial support of the Department of Higher Education and Training Teaching Grant for Scholarship of Teaching and Learning is hereby acknowledged.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Ensa Johnson

Ensa Johnson is a Lecturer,

Refilwe Morwane

Refilwe Morwane is a Lecturer, and

Shakila Dada

Shakila Dada is a Professor at the Centre for Augmentative and Alternative Communication, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

Gaby Pretorius

Gaby Pretorius is an Instructional Designer and

Marena Lotriet

Marena Lotriet is an Education Consultant in the Department for Education Innovation, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa.

References

- Baker, W., & Pittaway, S. (2012, July). The application of a student engagement framework to the teaching of music education in an e-learning context in one Australian university. Proceedings of the 4th Paris International Conference on Education, Economy and Society, Paris, France (pp. 27–38).

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191.

- Barkley, E. F. (2010). Student engagement techniques. A handbook for college faculty. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Brinthaupt, T. M., Fisher, L. S., Gardner, J. G., Raffo, D. M., & Woodard, J. B. (2011). What the best online teachers should do. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 7(4), 515–524.

- De Vos, A. S., Strydom, H., Fouché, C. B., & Delport, C. S. L. (2011). Research at grass roots: For the social sciences and human service professions. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

- Edwards, M., Perry, B., & Janzen, K. (2011). The making of an exemplary online educator. Distance Education, 32(1), 101–118.

- Frederickson, E., Shea, P., & Pickett, A. (2000). Factors influencing student and faculty satisfaction in the SUNY learning network. New York: State University of New York.

- Heilmann, J., Miller, J. F., Iglesias, A., Fabiano-Smith, L., Nockerts, A., & Andriacchi, K. D. (2008). Narrative transcription accuracy and reliability in two languages. Topics in Language Disorders, 28(2), 178–188.

- Hsieh, H., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288.

- In-On-Africa. (2013). Rural areas in the Eastern Cape Province, South Africa: The right to access safe drinking water and sanitation denied? Retrieved from http://www.polity.org.za/article/rural-areas-in-the-eastern-cape-province-south-africa-the-right-to-access-safe-drinking-water-and-sanitation-denied-2013-01-24

- Jefferies, A., & Hyde, R. (2010). Building the future student’s blended learning experience from current research findings. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 8(2), 133–140.

- Johnson, E., Nilsson, S., & Adolfsson, M. (2015). Eina! Ouch! Eish! Professionals’ perceptions of how children with Cerebral Palsy communicate about pain in South African school settings: Implications for the use of AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(4), 325–335.

- Krause, K. (2005). Understanding and promoting student engagement in university learning communities. University of Melbourne: Centre for the Study of Higher Education. Retrieved from http://www.liberty.edu/media/3425/teaching_resources/Stud_eng.pdf

- Malikowski, S. R., Thompson, M. E., & Theis, J. G. (2007). A model for research into course management systems: Bridging technology and learning theory. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 36(2), 149–173.

- Merriam, S. B. (2004). The changing landscape of adult learning theory. In J. Comings, B. Garner, & C. Smith (Eds.), Review of adult learning and literacy: Connecting research, policy, and practice (pp. 199–220). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Merriam, S. B. (2008). Adult learning theory for the twenty‐first century. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 2008(119), 93–98.

- Meydanlioglu, A., & Arikan, F. (2014). Effect of hybrid learning in higher education. World Academy of Science, Engineering and Technology, International Journal of Social, Behavioral, Educational, Economic, Business and Industrial Engineering, 8(5), 1283–1286.

- Morgan, G. (2003). Faculty use of course management systems (Vol. 2, pp. 1–97). Boulder, CO: EDUCAUSE Center for Applied Research (ECAR). Retrieved from http://www.educause.edu/ir/library/pdf/ers0302/rs/ers0302w.pdf

- Pittaway, S. M. (2012). Student and staff engagement: Developing an engagement framework in a Faculty of Education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 37(4), 3.

- Pittaway, S. M., & Moss, T. (2014). “Initially, we were just names on a computer screen”: Designing engagement in online teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(7), 8.

- Schutte, A. J., Kleingeld, M., & Pelzer, R. (2007). Demand-side energy management of a cascade mine surface refrigeration system. MEng dissertation. Potchefstroom, Northwest Province, South Africa: Department of Mechanical Engineering, Northwest University.

- Stanford-Bowers, D. E. (2008). Persistence in online classes: A study of perceptions among community college stakeholders. Journal of Online Learning and Teaching, 4(1), 37–50.

- Stone, C. (2012). Engaging students across distance and place. Journal of the Australia and New Zealand Student Services Association, 39, 49–55.

- Tomas, L., Lasen, M., Field, E., & Skamp, K. (2015). Promoting online students’ engagement and learning in science and sustainability preservice teacher education. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(11), 5.

- Unwin, T., Kleessen, B., Hollow, D., Williams, J. B., Oloo, L. M., Alwala, J., …Muianga, X. (2010). Digital learning management systems in Africa: Myths and realities. Open Learning, 25(1), 5–23.

- Waha, B., & Davis, K. (2014). University students’ perspective on blended learning. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(2), 172–182.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2000). Self-efficacy: An essential motive to learn. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 82–91.