Abstract

Rapid advancements in technology have led to Digital Technologies (DT) playing an increasingly prominent role in the digital transformation of education, prompting national and international educational policies to prioritize the embedding of DT in teaching and learning. However, this technological progress has simultaneously exposed a digital divide, resulting in certain parents and families, who are already socially excluded, being susceptible to digital exclusion. This article focuses on the influence of this subsequent digital exclusion on Parental Involvement (PI) in home-based digital learning, a crucial factor in supporting children navigate the digital transformation of education. Through a nonsystematic narrative literature review, this article addresses two research questions: first, how digital exclusion shapes PI in children’s home-based digital learning; and second, what approaches can schools employ to promote the digital inclusion of parents through shaping their self-efficacy for engaging with DT in support of PI. Emergent themes from the literature review include: the exclusionary impact of growing DT integration in education, the central role of PI in home-based digital learning, and the intertwined roles of self-efficacy and motivation in shaping PI. This article concludes with a discussion of considerations for school-based interventions, conceptualizes the link between PI and home-based digital learning, and proposes a call for future research.

Introduction

Digital Technologies (DT) are now ‘ubiquitous’ in citizens daily lives worldwide (UNESCO, Citation2023) rendering the possession of basic digital skills as a ‘pre-condition’ for actively participating in today’s society (EC, Citation2022). In response to this ‘socio-technical revolution’ (Tuomi et al., Citation2023) and reflective of “an ongoing worldwide digitalization of schools” (Grigic Magnusson et al., Citation2023, p. 318), twenty first century educational policies cognizant of the digital transformation of education place a heightened emphasis on the integration and embedding of DT into classroom practices (Gabriel et al., Citation2022; OECD, Citation2022), However, this advancement and spread of technology in education has exposed digital inequalities stemming from preexisting social inequalities (OECD, Citation2022; Scheerder et al., Citation2017; Van Dijk, Citation2020a). These inequalities have resulted in digital exclusion, a concept encapsulating “the range of external and internal factors that explain why people disengage from the internet” (Helsper & Reisdorf, Citation2017, p. 1253). The concept of digital inclusion is viewed as a response to this phenomenon by facilitating “an individual’s effective and sustainable engagement with Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) in ways that allow full participation in society in terms of economic, social, cultural, civic and personal well-being” (Helsper, Citation2014, p.1).

Addressing the risks of digital exclusion is vital to enable individual’s capacity to capitalize on the opportunities presented by the use of DT in teaching and learning (Fack et al., Citation2022). Parental Involvement (PI), defined as “the capacity of parents to act (in a beneficial manner) in relation to their children’s learning” (Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014, p. 401) and “a parents’ investment of various resources in their child education”(Ice & Hoover-Dempsey, Citation2011, p. 345), emerges as a potential mitigating factor in reducing digital exclusion for students. PI holds considerable importance in children’s education, primarily for supporting children’s learning (Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2020; Shute et al., Citation2011; Wilder, Citation2014), and PI also has a direct influence on student outcomes (Bower & Griffin, Citation2011; Bray et al., Citation2020; Davis-Kean, Citation2005; McCoy et al., Citation2014; McNamara et al., Citation2021; Smyth, Citation2018). The contemporary educational landscape now demands parents to support their children’s learning at home using DT, hereby referred to as ‘home-based digital learning’. To actively engage in support for this modern educational context, parents are required to possess basic digital skills (Livingstone et al., Citation2017). As we navigate the path of digital transformation of education, stakeholders in education should acknowledge the pivotal role of PI and its potential to be part of a digitally inclusive future for our students.

Various terms are used to conceptualize parents’ roles in education and their support for their children’s learning throughout the literature, including PI (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005; Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1995, Citation1997), Parental Engagement (PE) (Goodall, Citation2018; Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014), and Family, School, and Community Partnerships (Epstein, Citation1995, Citation2009; Epstein & Sheldon, Citation2022). Some distinctions are posited where PE is associated with children’s learning and PI with school activities (Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014; Goodall, Citation2018). Goodall and Montgomery (Citation2014) see involvement as taking part in an activity, whereas engagement is more agentic and provides a feeling of ownership. Despite these nuances, PI and PE are often used interchangeably in literature and policy documents resulting in a lack of consistency (O’Toole et al., Citation2021; Stefanski et al., Citation2016). Some studies use involvement when referring to parents supporting their children with homework when engagement may be seen to more in line with recent theory (Fitzmaurice et al., Citation2020) and other policy documents use PI and PE interchangeably (Munoz-Najar et al., Citation2021). Yet, Stefanski et al. (Citation2016) posit that neither focusing on the distinction between engagement and involvement fully captures the role of parents leading to a recent shift toward educational partnerships incorporating various actors including parents, family, school, teachers, and community (Hannon & O’Donnell, Citation2022; Stefanski et al., Citation2016). For clarity, this article utilizes the concept of PI throughout, with a specific focus on how this is operationalized in the home domain.

This article explores the intersection of the extant literature associated with digital exclusion and PI in the context of home-based digital learning. This exploration contributes to a deeper understanding of how digital exclusion influences PI and advocates for digitally inclusive school-based initiatives aimed at shaping parents’ self-efficacy in using DT to support their children’s home-based digital learning. Additionally, this article offers considerations for school leaders when planning to support PI through DT based initiatives. Schools striving to harness PI in digital learning are recommended to approach such initiatives with a constructive mindset toward digital inclusion, employing an approach of partnership with parents by seeking to increase their self-efficacy related to the use of DT in education. PI thus becomes a ‘tangible outcome’ (Helsper, Citation2012) that a digital inclusion intervention can address. Furthermore, this article seeks to add to the existing body of knowledge by presenting new insights into the relationship between digital exclusion and PI, proposing a framework for observing PI in home based digital learning, as well as suggesting potential directions for future research in this field. Exploring the intricate relationship between digital exclusion and PI is an underexplored area in current literature. This article aims to bridge this lacuna by addressing the following research questions:

How does digital exclusion shape parents’ capacity to support their children with home based digital learning?

What approaches can be employed by schools to promote the digital inclusion of parents in supporting children’s home-based digital learning?

Context

The digital transformation of education

The integration of DT into education accelerated globally during Covid-19 school closures and patently exposed digital inequalities (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020; Kuhfeld et al., Citation2020) and a ‘digital disconnect’ (Helsper, Citation2021). This period of ‘emergency remote teaching’ (Hodges et al., Citation2020) saw schools resorting to online instruction to counteract learning loss during closures, leading to the digital exclusion of students without access to devices and the internet and therefore no capacity to engage in schoolwork (Kuhfeld et al., Citation2020). The repercussions of this digital exclusion manifest in disparities in academic achievement (Kuhfeld et al., Citation2020) and divergent levels of student engagement from schools attended by students of low Socio-Economic Status (SES) and those of students of high SES (Flynn et al., Citation2021), resulting in an ‘ed tech tragedy’ for some (West, Citation2023). Factors associated with this lower level of engagement and achievement were interconnected with social inequality such as lack of access to devices and the internet (Kuhfeld et al., Citation2020; Mohan et al., Citation2021; UNICEF, Citation2022). A lack of parent involvement was also identified as a factor contributing to lower levels of student engagement during this period (Flynn et al., Citation2021; Winter et al., Citation2021).

The rationale for the post-pandemic increased use of DT in education is to equip students with twenty first century skills including digital literacy, critical thinking and collaboration (Scully et al., Citation2021). DT are seen as a key resource internationally in advancing quality and equity in education and training (OECD, Citation2023), influencing a number of digital education strategies across the globe (see van der Flies (Citation2020) for a comprehensive list). This vision is exemplified at the European Union (EU) policy level with the Digital Education Action Plan (DEAP) 2021—2027 (EC, Citation2020). The DEAP sets out a vision for a high-quality, inclusive and accessible digital education in Europe. It has two strategic priorities: 1. Fostering a high-performing digital education ecosystem supporting teachers and educators, and enhancing digital skills and competences; 2. Enhancing digital skills and competences for the digital transformation supporting the development of AI and data literacy, and promoting STEM education. This policy has exerted influence at the national level in European countries, as seen in Ireland’s Digital Strategy for Schools to 2027 (Department of Education, Ireland, Citation2022). Aligned with DEAP priorities, this strategy aims to deliver 1. A high performing digital ecosystem; and 2. Enhance digital competences for digital transformation. Importantly, this strategy lays out a vision of “embedding of digital technologies into teaching, learning and assessment” (Department of Education, Ireland, Citation2022, p. 16). This policy focus on developing digital skills has tangible consequences for those at risk of digital exclusion. Parents play a pivotal role in mitigating this exclusion for their children, with their level of PI shaped by their motivational beliefs, self-efficacy, agency and available resources (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005; Walker et al., Citation2005; Whitaker & Hoover-Dempsey, Citation2013).

Shifting discourse from digital exclusion to digital inclusion

The concept of digital exclusion has its origins in digital divide theory. The digital divide is recognized as being ‘super-complex (Kuhn et al., Citation2023) and even the term ‘digital divide’ itself is seen as problematic in the literature (Atherton et al., Citation2022). The original conceptualization of the digital divide was seen as binary based on levels of access to DT; one group was excluded, and the other was included (Katz & Aspden, Citation1997). The proliferation of technology and availability of the internet in society revealed that digital equality could not be achieved by access alone, ultimately users have to have the skills to reap the benefits for using DT in a purposeful manner (Hargittai, Citation2003). Selwyn (Citation2004) recognized the need to move beyond this dichotomous perspective toward a more realistic understanding of the reality of the digital divide which is multi-faceted and complex. Van Dijk (Citation2005) introduced a framework for this phenomenon, which involves a sequential process where the appropriation of technology occurs at three levels: 1. Access, 2. Usage, and 3. Outcomes. The first and second level divide are underpinned by four phases of access namely; motivation, physical access, skills, and usage. This third level divide focuses on the outcomes of the four phases of access, specifically “the benefits of having and using digital technology, or not having and using it” (Van Dijk, Citation2018, p. 204). The outcomes are where one sees the impact of the digital divide, resulting in a ‘digital outcomes’ divide (Scheerder et al., Citation2017).

Van Dijk (Citation2020b) states that there are several digital divides which are constantly evolving. These divides are “rooted in social and economic divides based around difference in power and resources” (p. 5) and refer to gaps between individuals and household of different SES in relation to their opportunities to access DT and to the outcomes of this use. Consequently, Atherton et al. (Citation2022) posit that conceptualizing the digital divide as multiple is more reflective of this reality, suggesting that the term ‘digital divides’ may be more appropriate. Indeed, divides is more prevalent in recent literature (Heeks, Citation2022; UNESCO, Citation2023; Vassilakopoulou & Hustad, Citation2023).

Contemporary discourse stemming from the digital divide now encompasses digital exclusion to graduations of digital inclusion (Helsper, Eynon, et al., Citation2015; Van Dijk, Citation2020a). Increased levels of access to DT and greater proliferation of internet use are seen as the factors contributing to this shift in the research agenda from the digital divide to digital inclusion (Van Deursen & Van Dijk, Citation2019). The shift led to an understanding of digital inclusion as “ensuring equity, inclusion, and gender equality in the use and access of digital devices and connectivity” (UNESCO, Citation2023, p. 28). This definition is symbiotically linked with the first (access) and second level (usage) of the digital divide (Van Dijk, Citation2005) and contends that digital inclusion is a response to bridge these levels. Furthermore, digital inclusion “is less determined by whether someone uses technologies and more by whether the nature of their use enhances their lives” (Helsper, Citation2012, p. 410), thus linking digital inclusion as a counter to the outcomes divide.

Methodology

This nonsystematic narrative literature review synthesizes the findings and demonstrates the importance of key theories and research studies (Green et al., Citation2006) by exploring the interplay between digital exclusion, digital inclusion, PI, and parental self-efficacy. A comprehensive search strategy was conducted using various scholarly databases, including Google Scholar, JSTOR and ERIC. This strategy involved using a range of targeted search terms, both individually and in various combinations, to gather the extant literature. These terms included: digital exclusion, digital inclusion, parental involvement, parental self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, and digital parenting self-efficacy. To further enhance the search, AI-based citation mapping tools, specifically Research Rabbit and Litmaps, were used. These advanced tools employ algorithms to identify and visualize citation links among articles, facilitating the tracking of ideas and connections within the research field. Consequently, they aided in the discovery of additional articles related to the search criteria that had been cited frequently in conjunction with seminal articles. Furthermore, the publications sections of supranational policy makers (European Commission (EC)) and international intergovernmental organizations (OECD, UNESCO, UNICEF, World Bank) were also explored to locate gray literature to DT and PI in education.

In line with a narrative review design, the selection criteria employed were not strict (Ferrari, Citation2015). The primary selection criteria (see ) were the relevance of the literature to the research questions (West & Martin, Citation2023). Additional broad inclusion criteria for the selected literature included peer-reviewed journal articles, books, book sections, conference papers, and papers published in the last twenty years. Similarly, broad exclusion criteria were applied to exclude literature that did not directly address the interrelationship between digital inclusion, PI, and home-based digital learning in a primary or secondary school context. Studies older than twenty years were excluded unless they were considered seminal or foundational to the research question.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria for the selection of resources on the effects of digital exclusion on PI in home-based digital learning.

Theoretical framework

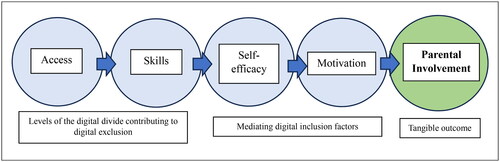

For the purposes of this article, a reimagined version of Helsper, Deursen, et al. (Citation2015) ‘Thematic development of the focus of digital inclusion debates’ framework was employed as an organizing frame to select the literature (see ). This frame visually represents the multi-faceted factors associated with digital inclusion namely, access to DT infrastructure, digital skills and digital literacy, motivation and awareness to use DT, and ability to engage with digital content culminating in tangible offline outcomes. This revised framework also incorporates the critical concepts of self-efficacy and motivation as integral factors contributing to PI in children’s home-based digital learning. Self-efficacy is included as it plays a pivotal role in understanding how individuals perceive their capability to effectively use DT. Furthermore, PI is regarded as a tangible outcome within this framework, representing the active involvement of parents in their children’s home-based digital learning. This revised framework not only guided the selection of relevant literature but also serves as a valuable tool for comprehending the interplay between these factors and their collective impact on digital inclusion and PI in the digital education landscape.

Figure 1. Thematic conceptualization of factors related to Digital Technologies (DT) contributing to Parental Involvement (PI) in children’s digital learning (Adapted from Helsper, Deursen, et al., Citation2015).

The analysis of the selected literature involved identifying patterns, trends, and emerging narrative themes related to the interrelationship between the factors in . The gaps in the existing literature were identified, and future research directions were proposed. In addition, the implications of the findings for schools were examined, with a specific emphasis on approaches for shaping PI in home-based digital learning.

Emergent themes from literature review

As global education systems navigate the digital transformation of education and seek to integrate and embed DT into teaching and learning activities, challenges emerge related to digital exclusion. This section, conducted within a framework encompassing factors related to digital exclusion and digital inclusion, reveals three emergent themes which act as a collective response to this paper first research question, specifically, how does digital exclusion shape parent’s capacity to support their children with home based digital learning? The subsequent sections discuss the interconnected effect of factors related to digital exclusion on PI, the central role of PI in supporting children with home-based digital learning, and the interrelated influence of parent’s self-efficacy and motivation on levels of PI. Each theme provides a nuanced understanding of the dynamic interplay between factors related to digital exclusion and PI.

Theme 1: the effect of digital exclusion factors on PI in the context of the digital transformation in education

Digital exclusion is a global, complex and multi-faceted issue with geo-educational disparities. This exclusion is characterized by a lack of digital access in the global south (Mammen et al., Citation2023), and despite significant recent investment in digitalization in this region, existing inequalities have been further exacerbated (Heeks, Citation2022). In more developed regions, such as the EU, where there is a policy emphasis on the use of DT in education, disparities still persist, particularly in terms of the beneficial outcomes arising from DT use (EC, Citation2020; Gabriel et al., Citation2022). A considerable amount of literature has been published in an effort to outline the causes of these disparities with almost uniform recognition that the digital divide and subsequent digital exclusion is rooted in preexisting social inequalities (Hargittai, Citation2010; Hargittai & Hinnant, Citation2008; Ragnedda, Citation2018; Scheerder et al., Citation2017; van Deursen et al., Citation2021; Van Dijk, Citation2005, Citation2020b). This assertion is supported by an abundance of literature positing that the side of the digital divide you reside is determined by socio-cultural and socio-economic factors (Beaunoyer et al, Citation2020, Gabriel et al, Citation2022; Helsper, Citation2012, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2016; Selwyn, Citation2004; Van Deursen & Helsper, Citation2018; Van Dijk, Citation2005, Citation2020a). Indeed, the OECD (Citation2020) suggests that individuals could be placed on a digital continuum with the primary influence being socio-economic factors, thus linking social factors with digital outcomes, a point echoed by Heeks (Citation2022). Factors related to digital exclusion manifest in different levels of digital engagement (Hornby & Lafaele, Citation2011; Livingstone & Helsper, Citation2007). Helsper (Citation2012) identifies four online and offline fields of exclusion which shape this engagement; economic, cultural, social, and personal. The author posits that the resources available in each of the four offline fields has a causal effect on the benefits one can derive from engaging in the four correlated digital fields. This concept is reinforced in literature where a lack of offline resources inhibits advances in the digital fields (OECD, Citation2016; Ragnedda, Citation2018; Van Deursen & Van Dijk, Citation2019). Accordingly, those families who are excluded offline will be presented with more barriers to overcome in keeping pace online with the digital transformation of education.

Digital transformation of education has brought to light the reality of digital exclusion which extends beyond mere access to DT; it is more about the meaningful use of these technologies to enhance individuals’ lives (Helsper, Citation2014). A study by Cheshmehzangi et al. (Citation2023) involving parents from 30 schools to assess correlations between the digital divide and education inequality identified barriers to digital inclusion in education as; access, digital literacy, age, gender, finance, privacy concerns, and support networks. Furthermore, a cross-national qualitative study by Austin et al. (Citation2023) investigated how parents adapted their involvement in digital education during this the Covid 19 pandemic and also examined the impact of SES on PI. The findings revealed that SES was not the sole predictor of the level of PI; rather, it was one of several complex factors, including parental expertise in ICT. This is echoed by research from O’Connor Bones et al. (Citation2022) which concluded that during the pandemic, as parents were compelled to support their child’s learning through ‘remote home-schooling,’ several factors including SES, family circumstances, and societal expectations influenced levels of PI.

Theme 2: the central role of PI in supporting children with home-based digital learning

PI is inherently influential in fostering children’s learning and plays a crucial role in determining educational outcomes. Understanding the central role of PI in a child’s education involves considering numerous influential variables identified in the literature including; parental education and family income (Davis-Kean, Citation2005), SES (EC, Citation2020; OECD, Citation2012), motivation (Deslandes & Bertrand, Citation2005; Green et al., Citation2007; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005), self-efficacy (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1995, Citation1997; Walker et al., Citation2005; Wittkowski et al., Citation2017), and race and family income (Desimone, Citation1999). Complementing these variables are a number of influential frameworks exist to conceptualize the central role of PI in children’s including; Epstein’s 6 Types of Parental Involvement (Epstein, Citation1995); The Parental Involvement Process Model (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005); School, Family, and Community Partnerships (Epstein, Citation2009); Parental Involvement to Engagement Continuum (Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014); and the Dual Navigation Approach (Jeynes, Citation2018). The multi-faceted operationalization of PI is outlined by Goodall and Montgomery (Citation2014) who categorize PI on a three-point continuum, ranging from PI with the school (e.g., attending a school information meeting), PI with schooling (e.g., attending a parent-teacher meeting), to PE with children’s learning (e.g., helping with homework). These forms of PI in children’s education are manifest in two categories, home based and school based (Boonk et al., Citation2018; Deslandes & Bertrand, Citation2005; Shute et al., Citation2011). Critically, “involvement at home is conceptually and empirically distinct from involvement at school” (Boonk et al., Citation2018, p.12), thus broadening our understanding of PI as it “refers to parent’s roles in educating their children at home and in school” (Deslandes & Bertrand, Citation2005, p.164).

Bradley & Corwyn’s HOME framework (2005) and Gregoriadis & Evangelou’s HLEC framework (2022) identify stimulation, parental instructions, parent-child interactions, and parental motivation as home-based factors contributing toward children’s engagement and experience in home-based learning. Bonanati and Buhl (Citation2022) refine these frameworks for the digital field by proposing the concept of the Digital Home Learning Environment (DHLE). This framework employs a DHLE consisting of stimulation, instructions, interactions, and modeling results in a better learning experience and outcomes for students. Research conducted in South Korea exploring PI in home-based digital learning by So et al. (Citation2022) characterize PI in home-based digital learning as a “complex and dynamic process” (p.1306). The research identified several factors, including parent’s beliefs, knowledge, skills, and access to the internet and DT play a role in influencing levels of PI. The findings highlight the significant effect of self-efficacy, knowledge, and skills in shaping how PI is manifested in supporting home-based digital learning.

Theme 3: the interrelated influence of parents’ self-efficacy and motivation on levels of PI

A symbiotic relationship exists between the self-efficacy of parents, their level of PI, and a child’s development (Ardelt & Eccles, Citation2001; Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014). Self-efficacy refers to “beliefs in one’s ability to organize and execute the course of action requires to produce given attainments” (Bandura, Citation1997, p. 3). Crucially, self-efficacy is not an indicator of an individual’s skills, instead it refers to what individuals perceive they can achieve with the skills they possess (Eastin & LaRose, Citation2006). One’s perceived level of self-efficacy also affects how much effort individuals will expend in the choice of activity and is also indicative of one’s motivation to participate in the activity (Bandura, Citation1997). From this broader theory of self-efficacy has emerged a number of sub-constructs including Parental Self-Efficacy(PSE) (Wittkowski et al., Citation2017) and a number related to digital technology including Computer Self-Efficacy (CSE) (Compeau & Higgins, Citation1995), Internet Self-Efficacy (ISE) (Eastin & LaRose, Citation2006), ICT and Digital Self-Efficacy (DSE) (Ulfert-Blank & Schmidt, Citation2022), and Digital Media Self-Efficacy (DMSE) (Hammer et al., Citation2021).

PSE is a key construct in the study of parenting and child development, defined as “the parent’s beliefs in his or her ability to influence the child and his or her environment to foster the child’s development and success (Ardelt & Eccles, Citation2001, p. 945). PSE also refers to parents’ beliefs in their ability to perform the parenting role successfully (Wittkowski et al., Citation2017). PSE and parental social networks are positively co-related with PI in home-based learning, with one study finding a direct link between PSE and proximal achievement outcomes (Ice & Hoover-Dempsey, Citation2011). These proximal outcomes are defined in this study as the contributory factors including student self-regulation, academic self-efficacy, and motivation which lead to concrete student success in academic terms. This intricate relationship is illuminated by the work of Oppermann et al. (Citation2021), who investigated how PSE and social supports act as protective factors for parents in managing challenges related to Home Learning Activities (HLA). Oppermann et al. (Citation2021) study yielded valuable insights into the dynamic interaction effects of PSE with stress related to HLA. High levels of PSE were found to mitigate the stress levels associated with changes in home learning.

Self-efficacy has also been identified as a crucial determinant of competent use of DT (Ulfert-Blank & Schmidt, Citation2022). Influential sub-constructs of self-efficacy determining DT use include CSE and ICT self-efficacy. CSE is described as ‘a multi-dimensional construct’ consisting of a number of factors which impact computer use (Chibisa et al., Citation2021), and also refers to “individuals’ beliefs about their ability to successfully use computers to solve tasks and manage situations” (Chen, Citation2017, p. 363). Bonanati & Buhl (Citation2022) define ICT self-efficacy as peoples “beliefs about their ability to successfully assess, evaluate, and manage information in the context of ICT”. Their study investigated the link between the Home Learning Environment (HLE) and children’s ICT self-efficacy. The authors operationalize PI in home based digital learning as parental support, consisting of strategies and activities to support children during DT use. Positive contributors to the development of children’s ICT self-efficacy identified in the study included families’ cultural capital, parents’ attitudes toward the Internet, and shared Internet activities at home. These sub-constructs of self-efficacy, particularly CSE and ICT self-efficacy, play a vital role in understanding the dynamics of PI in home-based digital learning, shedding light on the factors that influence children’s ICT self-efficacy and their digital inclusion.

A study by Huang et al. (Citation2018) combines the concepts of PSE, CSE, ICT self-efficacy and PI into a unified concept described as Digital Parenting Self-Efficacy (DPSE). This is defined as “parents’ perceived confidence in monitoring, guiding, and regulating their children’s internet activities” (p. 1189). This study focuses on parents in disadvantaged communities, aiming to address a gap in existing research concerning the dynamics of parent-child interactions related to digital access and use. The research revealed a positive correlation between PI in children’s school activities and DPSE. Active school engagement, such as attending parent courses, not only yields positive academic achievements but also boosts PSE. Additionally, possessing basic digital skills was found to have a significant impact on DPSE. Conversely, socio-demographic factors, SES, mobile internet access, parental expectations, and PI in homework were identified as noncontributory factors to an increase in DPSE. Furthermore,

Motivation serves as a dynamic driving force within the theory of PI and is considered one of its foundational factors (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1995, Citation1997; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005; Walker et al., Citation2005). PSE plays a crucial role in shaping parents’ motivation and, consequently, their forms of PI whether in the home or school domain (Walker et al., Citation2005). Motivation also acts as a constant driving factor across all levels of the digital divide, playing a central role in influencing digital inclusion (Van Dijk, Citation2018, p. 202). Therefore, it functions both as an enabler and a barrier within the digital realm (OECD, Citation2022). Understanding motivation’s multifaceted role is essential when examining its impact on PI and, consequently, its implications for children’s digital learning experiences. This underscores the critical interplay between motivation and various self-efficacy sub-constructs, collectively shaping the landscape of PI in the digital education sphere.

Discussion

The digital transformation of education has revealed the phenomenon of digital exclusion which inhibits an individual’s capacity to benefit from the use of DT (Helsper, Citation2014). While DT can serve as an educational lifeline for some, it simultaneously creates additional barriers to equal educational opportunities for others. These barriers often arise from socio-economic disparities and is further influenced by cultural norms (Helsper, Deursen, et al., Citation2015; Ragnedda, Citation2018), resulting in the emergence of new forms of digital exclusion including digital marginalization of parents with limited digital skills, motivation, and self-efficacy (UNESCO, Citation2023). This, in turn, has significant implications for PI in home-based digital learning.

This discussion section builds on the narrative themes emerging from the literature review which highlighted the effect of digital exclusion on PI and the importance of PSE in PI, to provide a response to the articles second research question, namely what approaches can be employed by schools to promote digital inclusion of parents in supporting children’s home-based digital learning? In the following sections a framework to conceptualize the association between self-efficacy, digital skills, and PI in home-based digital learning is proposed, and guidelines for schools seeking to introduce initiatives to promote the digital inclusion of parents are proffered.

Conceptualizing the association between self-efficacy, digital skills, and PI in home-based digital learning

This article underscores the intrinsic link between key constructs of PI, specifically self-efficacy and motivation, and their subsequent role in fostering digital inclusion for parents at risk of digital exclusion. Bandura’s Social Learning Theory (Bandura, Citation1986, Citation1997) emphasizes an individual’s self-efficacy, representing their confidence in their ability to undertake tasks. Incorporating this theory, Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler’s Parental Involvement Process model (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler Citation1995; Hoover-Dempsey & SandlerCitation1997; Walker et al., Citation2005) identifies PSE as a contributing factor to parent’s motivational beliefs, which in turn manifests in various forms of PI operationalized within home-based and school-based domains (Boonk et al., Citation2018). In addition, this article outlines how digital exclusion is intertwined with social exclusion and socio-economic disadvantage, leading to the emergence of a cohort of society characterized as a ‘digital underclass’ (Helsper & Reisdorf, Citation2017). These inequalities are outcomes of deep seated social inequality and are collectively labeled as digital exclusion (Beaunoyer et al., Citation2020; Helsper, Citation2012; Van Dijk, Citation2018), a term which accounts for the combination of complexities, internal and external factors that explain differences in engagement with ICT and the internet (Helsper & Reisdorf, Citation2017).

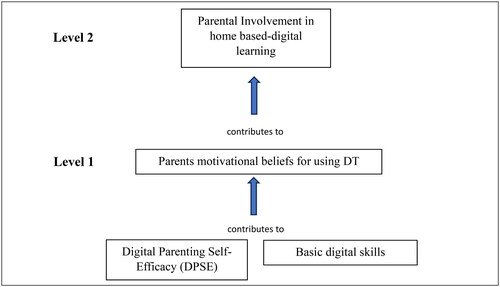

To adapt these theoretical underpinnings for PI in home-based digital learning, Huang et al.’s (Citation2018) concept of Digital Parenting Self-Efficacy (DPSE) synthesizing both PSE (Ardelt & Eccles, Citation2001) and CSE (Compeau & Higgins, Citation1995) is employed. Building on the work of So et al. (Citation2022), this reconceptualization, adapted from Level 1 and 2 of the Parental Involvement Process model (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation2005), DPSE is seen as contributing to DT motivational beliefs and, subsequently contributing to PI within home-based digital learning contexts (see ). Additionally, recognizing the importance of basic digital skills, we incorporate this element into the model as it is essential for meaningful digital participation. Livingstone et al. (Citation2017) echo this assertion by positing how parents’ digital skills and self-efficacy can be leveraged in support of children’s online opportunities and to enable them to fully benefit from digital resources. This interconnected relationship between DPSE and DT skills is a fundamental aspect of understanding individuals’ digital motivational beliefs, which, in turn, has implications for digital inclusion efforts.

Figure 2. Reconceptualized framework of level 1 and 2 of the Parental Involvement Process Model for PI in home-based digital learning (Adapted from Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation2005).

This reconceptualization highlights the significance of DPSE as a distinct construct from general self-efficacy in supporting children in the digital age. Adapting a framework posited by So et al. (Citation2022), it also acknowledges the contemporary relevance of digital skills in parenting. Furthermore, this reconceptualization offers a practical framework for schools to employ when seeking to promote PI in the digital domain. In doing so, the framework responds to the call made by Van Deursen and Helsper (Citation2018) to incorporate motivation and access as critical indicators in the conceptualization of digital divides.

Considerations for school-based interventions to promote PI in home-based digital learning

The growing integration of DT in education disproportionately affects families of low SES resulting in a ‘digital outcomes divide’ (Scheerder et al., Citation2017) and digital exclusion (Helsper, Citation2012). The EC (Citation2022) outlines the importance of promoting PI in children’s education while acknowledging that not all parents have these opportunities due to preexisting social inequalities. Although “it is not the task of school to solve societal problems” (Reid, Citation2019, p.780), schools may endeavor to proactively support those at risk of digital exclusion through targeted interventions. Ultimately, this article proposes that school-based programs designed to enhance parents’ digital skills and shape their DPSE have the potential to effect meaningful change for both parents and children.

Using the aforementioned model (see ) as a framework for designing school based interventions corresponds with Helsper’s (Citation2014) assertion that “successful digital inclusion initiatives start and end with the tangible (offline) outcomes and use access, skills, motivations and engagement with ICT to alleviate challenges encountered in the ‘real’ lives of disadvantaged groups” (p.2). Initiatives that foster family support contribute significantly to engaging parents in home-based learning activities (Ice & Hoover-Dempsey, Citation2011; Oppermann et al., Citation2021). Furthermore, Huang et al. (Citation2018) emphasize the positive outcomes of active school engagement, not only enhancing academic achievement but also PSE. Promising results have also been observed with low-tech PI behavioral interventions, as they contribute to enhancing PI levels (Goodall, Citation2018). This approach is echoed by Livingstone et al. (Citation2017), who suggest that “parents would welcome support for easy ways to increase their own digital skills and knowledge, and since parental digital competence and confidence results in more enabling efforts in relation to their children, the benefit of parental skills is felt among the whole family” (p. 22).

The first step in supporting parents to become involved in their children’s digital learning is to establish a relationship between the school and parents and to engage parents as partners in the teaching and learning process (Goodall, Citation2018; Munoz-Najar et al., Citation2021). By actively engaging parents in a school-based program, the parental agency will be increased (Boonk et al., Citation2018; Goodall & Montgomery, Citation2014). Next, building upon the recommendations proposed by Helsper (Citation2014), school leaders should consider the following steps:

Identify digital excluded parents in the school community (these parents are often marginalized in terms of social inclusion and equality);

Identify to what extent parents’ digital exclusion in terms of access, skills, motivation and engagement inhibits their level of PI;

Identify the best school personnel or external organizations to reach and help those most in need;

Implement an interactive contextualized digital skills course for parents aimed at shaping their self-efficacy and motivation in using the technology or digital learning applications their children use in school;

Evaluate the implementation and success of these initiatives by noting whether the parents have expressed improvement in their self-efficacy to successfully engage in home-based digital learning.

These proposed measures offer an inclusive approach for schools to mitigate digital exclusion by fostering and promoting PI in their students’ home-based digital learning. By identifying marginalized parents, assessing the extent of their digital exclusion, collaborating effectively, implementing targeted digital skills programs, and measuring the effectiveness of these initiatives, schools can play a pivotal role in bridging the digital divide and promoting PI. However, it is crucial to acknowledge that the success of these recommendations is contingent upon the availability of school personnel who can actively lead and facilitate these initiatives. While these steps hold promise in promoting digital inclusion and shaping PI, the practicality and effectiveness of these measures may vary depending on the resources and support available within each educational institution.

While interventions to bridge digital exclusion are common, a considered approach to their design and implementation is key to avoid exacerbating digital exclusion (Vassilakopoulou & Hustad, Citation2023). Interventions targeting CSE are seen as a determinant variable in developing computer or digital skills (Chibisa et al., Citation2021; Piccoli et al., Citation2001; Simmering et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, programs focused on basic digital skills can generate positive outcomes (Helsper, Citation2014), and schools can play a pivotal role in enhancing DPSE through more participatory involvement (Huang et al., Citation2018). An iterative design approach, as advocated by Vegas and Winthrop (Citation2020), has the potential to enhance education interventions and insights from Ní Chorcora et al. (Citation2023) suggest that multi-dimensional workshops, encompassing diverse components and involving parents and communities, exhibit promising potential as educational initiatives. Finally, as posited by Goodall (Citation2021), for parenting interventions to achieve consistent outcomes, they must be contextualized and acknowledge the cultural nuances of the participants; otherwise, outcomes are likely to vary.

Future research

As a prospect for future research, themes emerging from the literature review suggest designing interventions for parents at risk of digital exclusion through an iterative and participatory approach holds promise. This approach would encompass collaborative design, evaluation, and redesign, ensuring interventions are responsive to evolving needs and challenges. Embracing such a multifaceted approach holds the potential to significantly enhance the effectiveness of interventions, ultimately promoting PI and contributing to the broader goal of digital inclusion. Central to this approach is the acknowledgment of the barriers that contribute to digital exclusion, which can hinder parents from effectively engaging with DT.

Limitations

In this article every effort was made to address the complex and evolving topics of digital exclusion, digital inclusion, self-efficacy, and PI through a comprehensive review. However, in keeping with the style of narrative literature reviews, this article did not follow a systematic approach and therefore has its limitations (Hammersley, Citation2020; Oakley, Citation2007). By using broad search criteria, it is conceivable that some literature which fitted the criteria did not emerge and was therefore inadvertently excluded. During the initial stages of the search process, articles were selected based on their association with prominent scholars in the fields of digital exclusion and inclusion, as evidenced by a significant number of citations. Nevertheless, selecting literature that specifically linked digital exclusion with PI in home-based digital learning proved challenging. Consequently, the literature used in this article for PI and self-efficacy relies on establishing connections based on assertions made in the selected literature. This approach may have resulted in some articles or book chapters being unintentionally overlooked in this area.

Conclusion

This article was prompted by the rapid proliferation of DT in education and the concurrent emergence of a digital disconnect for those students at risk of digital exclusion which disproportionately affects individuals already socially marginalized (Helsper, Citation2021). Digital exclusion manifests at the first level as a lack of access to devices and the internet, and second, as disparities in the benefits derived from technological use. For parents facing digital disconnection, this results in a form of digital exclusion characterized by lower levels of digital skills and DPSE leading to lower levels of PI in home-based digital learning. In light of these developments, the primary aim of this article was to conduct a thorough and comprehensive examination of the existing literature pertaining specifically to PI in home-based digital learning.

Emergent themes from the literature review underline the central role of PI in a child’s digital learning journey and highlight the effect of digital exclusion on PI. To counteract such exclusion, PI is proposed as a complementary factor that can be harnessed through interventions which foster the digital inclusion of parents. School-based interventions have the potential to empower parents, mitigate some of the risks of digital exclusion, and position PI as a driving force for positive educational outcomes. This article suggests that interventions targeting PI in home-based digital learning should be thoughtfully designed with a focus on nurturing parents’ DT motivational beliefs through shaping DPSE and supporting the development of basic digital skills. Motivation emerges as a dynamic driver of PI in the literature, influencing the level of support for their children’s home-based digital learning. Self-efficacy, particularly DPSE, serves as the bridge between motivation and PI, translating intent into a tangible outcome. School-based interventions should aim to ignite and sustain this self-efficacy and motivation, emphasizing the transformative potential of enhanced DPSE. As we continue to navigate the evolving digital educational landscape, education stakeholders should recognize the significance of PI and its capacity to shape a digitally inclusive future for our students. Ultimately, the transformative potential of DT in education can only be realized by a commitment to digital inclusion, reflected in both policies and school-based initiatives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ardelt, M., & Eccles, J. S. (2001). Effects of mothers’ parental efficacy beliefs and promotive parenting strategies on inner-city youth. Journal of Family Issues, 22(8), 944–972. doi:10.1177/019251301022008001

- Atherton, G., Crosling, G., Hoong, A. L. S., Elson-Rogers, S. (2022). How do digital competence frameworks address the digital divide? https://unevoc.unesco.org/up/How_do_digital_competence_frameworks_address_the_digital_divide.pdf

- Austin, R., Angeli-Valanides, C., Brown, M., & Taggart, S. (2023). From gatekeeper to proto-online tutor: The role of parents in digital education. Studies in Technology Enhanced Learning, 3(3). doi:10.21428/8c225f6e.8b56c2b9

- Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory (pp. 13, 617). Prentice-Hall, Inc.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W.H. Freeman.

- Beaunoyer, E., Dupéré, S., & Guitton, M. J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital inequalities: Reciprocal impacts and mitigation strategies. Computers in Human Behavior, 111, 106424. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106424

- Bonanati, S., & Buhl, H. M. (2022). The digital home learning environment and its relation to children’s ICT self-efficacy. Learning Environments Research, 25(2), 485–505. doi:10.1007/s10984-021-09377-8

- Boonk, L., Gijselaers, H. J. M., Ritzen, H., & Brand-Gruwel, S. (2018). A review of the relationship between parental involvement indicators and academic achievement. Educational Research Review, 24, 10–30. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2018.02.001

- Bower, H. A., & Griffin, D. (2011). Can the Epstein model of parental involvement work in a high-minority, high-poverty elementary school? A case study. Professional School Counseling, 15(2), 2156759X1101500. doi:10.1177/2156759X1101500201

- Bradley, R., & Corwyn, R. (2005). Caring for children around the world: A view from HOME. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 29(6), 468–478. doi:10.1177/01650250500146925

- Bray, A., Ní Chorcora, E., Maguire Donohue, E., Banks, J., & Devitt, A. (2020). Post-primary student perspectives on teaching and learning during Covid-19 School Closures: Lessons learned from Irish Students from School in a Widening Participation Programme. Trinity College Dublin.

- Chen, I.-S. (2017). Computer self-efficacy, learning performance, and the mediating role of learning engagement. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 362–370. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.059

- Cheshmehzangi, A., Zou, T., Su, Z., & Tang, T. (2023). The growing digital divide in education among primary and secondary children during the COVID-19 pandemic: An overview of social exclusion and education equality issues. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 33(3), 434–449. doi:10.1080/10911359.2022.2062515

- Chibisa, A., Tshabalala, M., & Maphalala, M. (2021). Pre-service teachers’ computer self-efficacy and the use of computers. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 20(11), 325–345. doi:10.26803/ijlter.20.11.18

- Compeau, D. R., & Higgins, C. A. (1995). Computer self-efficacy: Development of a measure and initial test. MIS Quarterly, 19(2), 189–211. doi:10.2307/249688

- Davis-Kean, P. E. (2005). The influence of parent education and family income on child achievement: The indirect role of parental expectations and the home environment. Journal of Family Psychology, 19(2), 294–304. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.19.2.294

- Department of Education, Ireland. (2022). Digital strategy for schools to 2027. Stationery Office. www.gov.ie

- Desimone, L. (1999). Linking parent involvement with student achievement: Do race and income matter?. The Journal of Educational Research, 93(1), 11–30. doi:10.1080/00220679909597625

- Deslandes, R., & Bertrand, R. (2005). Motivation of parent involvement in secondary-level schooling. The Journal of Educational Research, 98(3), 164–175. doi:10.3200/JOER.98.3.164-175

- Eastin, M. S., & LaRose, R. (2006). Internet self-efficacy and the psychology of the digital divide. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 6(1), 1–18. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2000.tb00110.x

- Epstein, J. L. (1995). School/family/community partnerships: Caring for the children we share. The Phi Delta Kappan, 76(9), 701–712. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20405436

- Epstein, J. L. (2009). School, family, and community partnerships; your handbook for action (3rd ed.). Corwin Press Inc. https://www.proquest.com/docview/199688727/citation/E904F2DF82BF42D9PQ/1

- Epstein, J. L., & Sheldon, S. B. (2022). School, family, and community partnerships: Preparing educators and improving schools (3rd ed.). Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780429400780

- European Commission (EC). (2020). Digital education action plan 2021 – 2027. Resetting education and training for the digital age. Publications Office of the European Union. https://ec.europa.eu/education/sites/default/files/document-library-docs/deap-communication-sept2020_en.pdf

- European Commission (EC). (2022). Interim report of the commission expert group on quality investment in education and training. Publications Office of the European Union. doi:10.2766/37858

- Fack, G., Agasisti, T., Bonal, X., De Witte, K., Dohmen, D., Haase, S., Hylen, J., McCoy, S., Neycheva, M., Carmen Pantea, M., Pastore, F., Pausits, A., Poder, K., Puukka, J., Velissaratou, J. (2022). Interim report of the Commission expert group on quality investment in education and training. https://www.esri.ie/publications/interim-report-of-the-commission-expert-group-on-quality-investment-in-education-and

- Ferrari, R. (2015). Writing narrative style literature reviews. Medical Writing, 24(4), 230–235. doi:10.1179/2047480615Z.000000000329

- Fitzmaurice, H., Flynn, M., & Hanafin, J. (2020). Parental involvement in homework: A qualitative Bourdieusian study of class, privilege, and social reproduction. International Studies in Sociology of Education, 30(4), 440–461. doi:10.1080/09620214.2020.1789490

- Flynn, N., Keane, E., Davitt, E., McCauley, V., Heinz, M., & Mac Ruairc, G. (2021). Schooling at home’ in Ireland during COVID-19’: Parents’ and students’ perspectives on overall impact, continuity of interest, and impact on learning. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 217–226. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916558

- Gabriel, F., Marrone, R., Van Sebille, Y., Kovanovic, V., & de Laat, M. (2022). Digital education strategies around the world: Practices and policies. Irish Educational Studies, 41(1), 85–106. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.2022513

- Goodall, J. (2018). Learning-centred parental engagement: Freire reimagined. Educational Review, 70(5), 603–621. doi:10.1080/00131911.2017.1358697

- Goodall, J. (2021). Parental engagement and deficit discourses: Absolving the system and solving parents. Educational Review, 73(1), 98–110. doi:10.1080/00131911.2018.1559801

- Goodall, J., & Montgomery, C. (2014). Parental involvement to parental engagement: A continuum. Educational Review, 66(4), 399–410. doi:10.1080/00131911.2013.781576

- Green, B. N., Johnson, C. D., & Adams, A. (2006). Writing narrative literature reviews for peer-reviewed journals: Secrets of the trade. Journal of Chiropractic Medicine, 5(3), 101–117. doi:10.1016/S0899-3467(07)60142-6

- Green, C. L., Walker, J. M. T., Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (2007). Parents’ motivations for involvement in children’s education: An empirical test of a theoretical model of parental involvement. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(3), 532–544. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.99.3.532

- Gregoriadis, A., & Evangelou, M. (2022). Revisiting the home learning environment: Introducing the home learning ecosystem. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 47(3), 206–218. doi:10.1177/18369391221099370

- Grigic Magnusson, A., Ott, T., Hård af Segerstad, Y., & Sofkova Hashemi, S. (2023). Complexities of managing a mobile phone ban in the digitalized schools’ classroom. Computers in the Schools, 40(3), 303–323. doi:10.1080/07380569.2023.2211062

- Hammer, M., Scheiter, K., & Stürmer, K. (2021). New technology, new role of parents: How parents’ beliefs and behavior affect students’ digital media self-efficacy. Computers in Human Behavior, 116, 106642. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106642

- Hammersley, M. (2020). Reflections on the methodological approach of systematic reviews. In O. Zawacki-Richter, M. Kerres, S. Bedenlier, M. Bond, & K. Buntins (Eds.), Systematic reviews in educational research: Methodology, perspectives and application (pp. 23–39). Springer Fachmedien. doi:10.1007/978-3-658-27602-7_2

- Hannon, L., & O’Donnell, G. (2022). Teachers, parents, and family-school partnerships: Emotions, experiences, and advocacy. Journal of Education for Teaching, 48(2), 241–255. doi:10.1080/02607476.2021.1989981

- Hargittai, E. (2003). The digital divide and what to do about it. In D. C. Jones (Ed.), New economy handbook (pp. 822–841). Academic Press.

- Hargittai, E. (2010). Digital Na(t)ives? Variation in internet skills and uses among members of the “net generation”. Sociological Inquiry, 80(1), 92–113. doi:10.1111/j.1475-682X.2009.00317.x

- Hargittai, E., & Hinnant, A. (2008). Digital inequality: Differences in young adults’ use of the internet. Communication Research, 35(5), 602–621. doi:10.1177/0093650208321782

- Heeks, R. (2022). Digital inequality beyond the digital divide: Conceptualizing adverse digital incorporation in the global South. Information Technology for Development, 28(4), 688–704. doi:10.1080/02681102.2022.2068492

- Helsper, E. J. (2012). A corresponding fields model for the links between social and digital exclusion. Communication Theory, 22(4), 403–426. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2012.01416.x

- Helsper, E. J. (2014). Harnessing ICT for social action—A digital volunteering programme—Publications Office of the EU. https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/fca07689-151e-49e2-b8e1-e8ffe25f786c/language-en/format-PDF

- Helsper, E. J. (2021). The digital disconnect: The social causes and consequences of digital inequalities. SAGE.

- Helsper, E. J., & Reisdorf, B. (2017). The emergence of a “digital underclass” in Great Britain and Sweden: Changing reasons for digital exclusion. New Media & Society, 19(8), 1253–1270. doi:10.1177/14614448166346

- Helsper, E. J., Eynon, R., van Deursen, A. J. A. M. (2015). From digital skills to tangible outcomes project report. www.oii.ox.ac.uk/research/projects/?id=112

- Helsper, E., Deursen, A. J. A. M., & Eynon, R. (2015). Tangible outcomes of internet use. doi:10.13140/RG.2.1.1117.6722

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., Bond, M. (2020). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference-between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1995). Parental involvement in children’s education: Why does it make a difference? Teachers College Record, 97(2), 310–331. doi:10.1177/016146819509700202

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3–42. doi:10.2307/1170618

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Sandler, H. M. (2005). Final performance report for OERI Grant # R305T010673: The social context of parental involvement: A path to enhanced achievement. https://ir.vanderbilt.edu/handle/1803/7595

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130. doi:10.1086/499194

- Hornby, G., & Lafaele, R. (2011). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An explanatory model. Educational Review, 63(1), 37–52. doi:10.1080/00131911.2010.488049

- Huang, G., Li, X., Chen, W., & Straubhaar, J. D. (2018). Fall-behind parents? The influential factors on digital parenting self-efficacy in disadvantaged communities. American Behavioral Scientist, 62(9), 1186–1206. doi:10.1177/0002764218773820

- Ice, C. L., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. V. (2011). Linking parental motivations for involvement and student proximal achievement outcomes in homeschooling and public schooling settings. Education and Urban Society, 43(3), 339–369. doi:10.1177/0013124510380418

- Jeynes, W. H. (2018). A practical model for school leaders to encourage parental involvement and parental engagement. School Leadership & Management, 38(2), 147–163. doi:10.1080/13632434.2018.1434767

- Katz, J., & Aspden, P. (1997). Motivations for and barriers to Internet usage: Results of a national public opinion survey. Internet Research, 7(3), 170–188. doi:10.1108/10662249710171814

- Kuhfeld, M., Soland, J., Tarasawa, B., Johnson, A., Ruzek, E., & Liu, J. (2020). Projecting the potential impact of COVID-19 school closures on academic achievement. Educational Researcher, 49(8), 549–565. doi:10.3102/0013189X20965918

- Kuhn, C., Khoo, S.-M., Czerniewicz, L., Lilley, W., Bute, S., Crean, A., Abegglen, S., Burns, T., Sinfield, S., Jandrić, P., Knox, J., & MacKenzie, A. (2023). Understanding digital inequality: A theoretical kaleidoscope. Postdigital Science and Education, 5(3), 894–932. doi:10.1007/s42438-023-00395-8

- Livingstone, S., & Helsper, E. (2007). Gradations in digital inclusion: Children, young people and the digital divide. New Media & Society, 9(4), 671–696. doi:10.1177/1461444807080335

- Livingstone, S., Ólafsson, K., Helsper, E. J., Lupiáñez-Villanueva, F., Veltri, G. A., & Folkvord, F. (2017). Maximizing opportunities and minimizing risks for children online: The role of digital skills in emerging strategies of parental mediation. Journal of Communication, 67(1), 82–105. doi:10.1111/jcom.12277

- Mammen, J. T., Rugmini Devi, M., & Girish Kumar, R. (2023). North–South digital divide: A comparative study of personal and positional inequalities in USA and India. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 15(4), 482–495. doi:10.1080/20421338.2022.2129343

- McCoy, S., Smyth, E., & Watson, D. (2014). Leaving school in Ireland: A longitudinal study of post school transitions. ESRI. Research Series Number 36. https://www.esri.ie/system/files/publications/RS36.pdf

- McNamara, E., O’Mahoney, D., McClintock, R., Murray, A., Smyth, E., Watson, D. (2021). The lives of 20-year-olds: Making the transition to adulthood. ESRI. https://www.esri.ie/publications/growing-up-in-ireland-the-lives-of-20-year-olds-making-the-transition-to-adulthood

- Mohan, G., Carroll, E., McCoy, S., Mac Domhnaill, C., & Mihut, G. (2021). Magnifying inequality? Home learning environments and social reproduction during school closures in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 265–274. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1915841

- Munoz-Najar, A., Gilberto, A., Hasan, A., Cobo, C., Azevedo, J. P., & Akmal, M. (2021). Remote learning during COVID-19: Lessons from today, principles for tomorrow. World Bank. doi:10.1596/36665

- Ní Chorcora, E., Bray, A., & Banks, J. (2023). A systematic review of widening participation: Exploring the effectiveness of outreach programmes for students in second‐level schools. Review of Education, 11(2), e3406. doi:10.1002/rev3.3406

- O’Connor Bones, U., Bates, J., Finlay, J., & Campbell, A. (2022). Parental involvement during COVID-19: Experiences from the special school. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 37(6), 936–949. doi:10.1080/08856257.2021.1967297

- O’Toole, L., Kiely, J., McGillacuddy, D., O’Brien, E. Z., O’Keeffe, C. (2021). Parental involvement, engagement and partnership in their children’s education during the primary school years. National Parents Council Primary. https://www.npc.ie/news-events/parental-involvement-engagement-and-partnership-in-their-childrens-educatio

- Oakley, A. (2007). Evidence-informed policy and practice: Challenges for social science In M. Hammersley (Ed.), Educational research and evidence-based practice (pp. 91–105). Open University Press.

- OECD. (2012). Equity and quality in education: Supporting disadvantaged students and schools. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.ilibrary.org/education/equity-and-quality-in-education_9789264130852-en

- OECD. (2016). Are there differences in how advantaged and disadvantaged students use the Internet? (PISA in Focus 64; PISA in Focus, Vol. 64). doi:10.1787/5jlv8zq6hw43-en

- OECD. (2020). Education in the digital age: Healthy and happy children. OECD. doi:10.1787/1209166a-en

- OECD. (2022). Trends shaping education 2022. OECD. doi:10.1787/6ae8771a-en

- OECD. (2023). Shaping digital education: Enabling factors for quality, equity and efficiency. OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/content/publication/bac4dc9f-en

- Oppermann, E., Cohen, F., Wolf, K., Burghardt, L., & Anders, Y. (2021). Changes in parents’ home learning activities with their children during the COVID-19 lockdown – The role of parental stress, parents’ self-efficacy and social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 682540. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.682540

- Piccoli, G., Ahmad, R., & Ives, B. (2001). Web-based virtual learning environments: A research framework and a preliminary assessment of effectiveness in basic IT skills training. MIS Quarterly, 25(4), 401–426. doi:10.2307/3250989

- Ragnedda, M. (2018). Conceptualizing digital capital. Telematics and Informatics, 35(8), 2366–2375. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2018.10.006

- Reid, A. (2019). Climate change education and research: Possibilities and potentials versus problems and perils? Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 767–790. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1664075

- Scheerder, A., Van Deursen, A., & Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2017). Determinants of Internet skills, uses and outcomes. A systematic review of the second-and third-level digital divide. Telematics and Informatics, 34(8), 1607–1624. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2017.07.007

- Scully, D., Lehane, P., & Scully, C. (2021). It is no longer scary: Digital learning before and during the Covid-19 pandemic in Irish secondary schools. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 30(1), 159–181. doi:10.1080/1475939X.2020.1854844

- Selwyn, N. (2004). Reconsidering political and popular understandings of the digital divide. New Media & Society, 6(3), 341–362. doi:10.1177/1461444804042519

- Shute, V., Hansen, E., Underwood, J., & Razzouk, R. (2011). A review of the relationship between parental involvement and secondary school students’ academic achievement. Education Research International, 2011, 1–10. doi:10.1155/2011/915326

- Simmering, M. J., Posey, C., & Piccoli, G. (2009). Computer self-efficacy and motivation to learn in a self-directed online course. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 7(1), 99–121. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4609.2008.00207.x

- Smyth, E. (2018). Shaping educational expectations: The perspectives of 13-year-olds and their parents. Educational Review, 72(2), 173–195. doi:10.1080/00131911.2018.1492518

- So, H.-J., Shin, S., Xiong, Y., & Kim, H. (2022). Parental involvement in digital home-based learning during COVID-19: An exploratory study with Korean parents. Educational Psychology, 42(10), 1301–1321. doi:10.1080/01443410.2022.2078479

- Stefanski, A., Valli, L., & Jacobson, R. (2016). Beyond involvement and engagement: The role of the family in school–community partnerships. School Community Journal, 26(2), 135–160.

- Tuomi, I., Cachia, R., & Villar, O. D. (2023). On the futures of technology in education: Emerging trends and policy implications. JRC Publications Repository. doi:10.2760/079734

- Ulfert-Blank, A.-S., & Schmidt, I. (2022). Assessing digital self-efficacy: Review and scale development. Computers & Education, 191, 104626. doi:10.1016/j.compedu.2022.104626

- UNESCO. (2023). Global education monitoring report 2023: Technology in education—A tool on whose terms? UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000385723

- UNICEF. (2022). Are children really learning? Exploring foundational skills in the midst of a learning crisis. UNICEF. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED619064

- van der Flies, R. (2020). Digital strategies in education across OECD countries: Exploring education policies on digital technologies. OECD Education Working Papers, 226. doi:10.1787/33dd4c26-en

- Van Deursen, A. J., & Helsper, E. J. (2018). Collateral benefits of Internet use: Explaining the diverse outcomes of engaging with the Internet. New Media & Society, 20(7), 2333–2351. doi:10.1177/1461444817715282

- van Deursen, A. J., & van Dijk, J. A. (2019). The first-level digital divide shifts from inequalities in physical access to inequalities in material access. New Media & Society, 21(2), 354–375. doi:10.1177/1461444818797082

- van Deursen, A. J. A. M., van der Zeeuw, A., de Boer, P., Jansen, G., & van Rompay, T. (2021). Digital inequalities in the internet of things: Differences in attitudes, material access, skills, and usage. Information, Communication & Society, 24(2), 258–276. doi:10.1080/1369118X.2019.1646777

- van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2005). The deepening divide: Inequality in the information society. SAGE. doi:10.4135/9781452229812

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2018). Afterword: The state of digital divide theory. In M. Ragnedda & G. Muschert (Eds.), Theorizing digital divides (pp. 199–206). Routledge. https://www-taylorfrancis-com.ucd.idm.oclc.org/chapters/edit/10.4324/9781315455334-16/afterword-jan-van-dijk

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2020a). The digital divide. John Wiley & Sons.

- Van Dijk, J. A. G. M. (2020b). Closing the digital divide: The role of digital technologies on social development, well-being of all and the approach of the Covid-19 pandemic. https://www.un.org/development/desa/dspd/wp-content/uploads/sites/22/2020/07/Closing-the-Digital-Divide-by-Jan-A.G.M-van-Dijk-.pdf

- Vassilakopoulou, P., & Hustad, E. (2023). Bridging digital divides: A literature review and research agenda for information systems research. Information Systems Frontiers, 25(3), 955–969. doi:10.1007/s10796-020-10096-3

- Vegas, E., Winthrop, R. (2020). Beyond reopening schools: How education can emerge stronger than before COVID-19. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/beyond-reopening-schools-how-education-can-emerge-stronger-than-before-covid-19/

- Walker, J., Wilkins, A., Dallaire, J., Sandler, H., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. (2005). Parental involvement: Model revision through scale development. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 85–104. doi:10.1086/499193

- West, M. (2023). An ed-tech tragedy? Educational technologies and school closures in the time of COVID-19. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000386701

- West, R. E., & Martin, F. (2023). What type of paper are you writing? A taxonomy of review and theory scholarship distinguished by their summary and advocacy arguments. Educational Technology Research and Development, 1–34. doi:10.1007/s11423-023-10233-0

- Whitaker, M., & Hoover-Dempsey, K. (2013). School influences on parents’ role beliefs. The Elementary School Journal, 114(1), 73–99. doi:10.1086/671061

- Wilder, S. (2014). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. Educational Review, 66(3), 377–397. doi:10.1080/00131911.2013.780009

- Winter, E., Costello, A., O’Brien, M., & Hickey, G. (2021). Teachers’ use of technology and the impact of Covid-19. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 235–246. doi:10.1080/03323315.2021.1916559

- Wittkowski, A., Garrett, C., Calam, R., & Weisberg, D. (2017). Self-report measures of parental self-efficacy: A systematic review of the current literature. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(11), 2960–2978. doi:10.1007/s10826-017-0830-5