Abstract

A comprehensive description of the factors associated with job satisfaction among occupational therapy practitioners is needed to promote their work well-being. This systematic review aimed to describe occupational therapy practitioners’ job satisfaction and the related intra-, inter-, and extra-personal factors. Original peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2019 were retrieved from four databases with the review including fourteen studies. The review was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute guideline. The data were analyzed by narrative synthesis. Occupational therapy practitioners experienced high job satisfaction. Job satisfaction was found to be associated with significantly lower rates of turnover intention and higher rates of rewards. The relationships between job satisfaction, professional identity, exhaustion, and social environment showed conflicting results.

Introduction

Job satisfaction affects professional commitment, increasing organizational stability (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011; Lu et al., Citation2019). The retention and turnover of staff is relevant for health care as an increasing number of health care professionals will be needed in the coming years to meet the global demand for health services (WHO, Citation2016). Several reviews of health care professionals such as midwives (Bloxsome et al., Citation2019) and nurses (Caers et al., Citation2008; Friganović et al., Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2019), have found that job satisfaction decreases staff turnover. In addition, studies have shown that job satisfaction among health care workers significantly affects certain dimensions of burnout (Dilig-Ruiz et al., Citation2018; Friganović et al., Citation2019; Tarcan et al., Citation2017). For instance, nurses with higher levels of job satisfaction showed only moderate exhaustion (Friganović et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, it has been shown that emotional exhaustion negatively affects the job satisfaction of not only nurses but also that of doctors and medical technicians (Tarcan et al., Citation2017). Recent studies have found that the risk of developing burnout varies widely among occupational therapists (Bruschini et al., Citation2018; Derakhshanrad et al., Citation2019; Escudero-Escudero et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020; Reis et al., Citation2018).

Recent international research into occupational therapists’ work well-being has mainly focused on negative aspects, for instance, burnout (e.g. Escudero-Escudero et al., Citation2020; Kim et al., Citation2020) and workplace fatigue (Brown et al., Citation2017). However, research in this field should also take into account positive aspects (e.g., job satisfaction) in order to provide a comprehensive description of work well-being (Turner et al., Citation2002).

Job satisfaction is generally defined as an individual’s global sense of work, along with their attitudes toward work-related facets such as colleagues, communication, and operating conditions (Spector, Citation1997). Applying a global perspective will involve scrutinizing an individual’s attitude map when defining the effects of job satisfaction or dissatisfaction (Spector, Citation1997). This approach can provide a broader picture of job satisfaction than a questionnaire that covers different facets of satisfaction (Highhouse & Becker, Citation1993). Khan and colleagues (2010) have identified from several front-line content and process theories of employees’ job satisfaction (e.g., Two-Factor Theory (Herzberg et al., Citation2010) Goal-Setting Theory (Locke & Latham, Citation2002)) a set of four themes: human requirements, effort/performance, rewards, and satisfaction. Since human needs comprise physical, cognitive, and social aspects, effort refers to the actions that humans use to meet these requirements which is affected by personal, work, environmental, and organizational characteristics. Regarding rewards, individuals gain internal and external satisfaction for good behavior. An employee will be satisfied with their job when they positively perceive all of these factors (Khan et al., Citation2010). Traditional theories of employee job satisfaction include the four aforementioned aspects, yet also emphasize two additional attributes, namely, happiness with working conditions and job value or equity. Individual, emotional, and environmental factors, along with job characteristics, affect these identified attributes (Liu et al., Citation2016).

Based on the Effort-Reward Imbalance (ERI) model (Siegrist, Citation1996), any imbalance between rewards (e.g., monetary rewards, esteem, career opportunities, status control), external efforts (e.g., demands, obligations) and internal efforts (e.g., employee’s need for control) will reduce job satisfaction (Devonish, Citation2018). In contrast, the Job Demand-Control (JDC) model states that job dissatisfaction is reinforced when the demands of a job increase as an employee’s control over the job decreases (Karasek, Citation1979). In this model, job demands include time pressure, excessive workload, and role conflicts, whereas job control comprises opportunities for influence related to the content of one’s own work, working conditions, and competence development (Karasek & Theorell, Citation1990).

Recent models of job satisfaction have focused on describing job satisfaction through attitudes (Carter et al., Citation2020) and examining the significance of certain values (Kaya & Boz, 2019). Carter et al. (Citation2020) described employees’ job satisfaction through The Causal Attitude Network (CAN) model (Dalege et al., Citation2016), in which job satisfaction is described as an attitude. The distinction between instrumental and symbolic features of work-related attitudes is evident in job satisfaction networks. Instrumental job features (or attitude objects related to work), such as pay and promotion, are stable and highly connected to each other. Instead, the connections between symbolic attitude objects, for instance, coworkers, supervisors, or one’s job in general, become stronger with job tenure (Carter et al., Citation2020). The Professional Values Model in Nursing, developed by Kaya and Boz (Citation2019), introduces relationships between job satisfaction, patient satisfaction, and professional and individual values. Based on this model, professional values significantly contribute to job satisfaction (Kaya & Boz, 2019).

Both employee characteristics (i.e. intra-personal factors), and interaction with other people (i.e. inter-personal factors), contribute to job satisfaction (Hayes et al., Citation2010). Humanism in the work of occupational therapists has been shown to be related to job satisfaction (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011). Job satisfaction of occupational therapists is affected by patient-related factors, such as the fulfillment of therapy goals, and interaction (Seah et al., Citation2011) and in general working with clients (Davey et al., Citation2014). Moreover, sense of self—which is influenced by meeting expectations and receiving feedback (Seah et al., Citation2011)—and substance knowledge and skills (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011) have also been reported to enhance job satisfaction among occupational therapists.

Coworkers and team members are meaningful roles that contribute to occupational therapists’ job satisfaction (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011) while job satisfaction is limited by decreasing possibilities for supervision by colleagues. Instead, the balance between autonomy and authority, capability, and coupling constraints influenced job satisfaction (Bendixen & Ellegård, Citation2014). Similarly Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al. (Citation2011) have previously showed that freedom and flexibility at work were related to job satisfaction. On the other hand, job dissatisfaction was affected by other health care professionals’ lack of awareness about occupational therapy and lack of advocacy (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011).

External factors, occasionally referred to as extra-personal factors, can also affect an employee’s job satisfaction (Hayes et al., Citation2010). Job dissatisfaction among occupational therapists has previously been attributed to organizational factors, such as time limitations, excessive administrative paperwork (Davey et al., Citation2014), limited availability of treatment and assessment tools, overlooked areas of practice (such as home-based occupational therapy), and poor work benefits (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011). Additionally, enough therapy space for implementation of occupational therapy affected job satisfaction (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011).

A database search did not identify any previous systematic review that had investigated job satisfaction from the perspective of occupational therapy practitioners, so compiling and summarizing information on job satisfaction among occupational therapy practitioners—as well as assessing the quality of prior empirical research—is justified. This systematic review, which describes job satisfaction among occupational therapy practitioners, was guided by the following research questions:

What is the level of job satisfaction among occupational therapy practitioners?

Which intra-, inter-, and extra-personal factors are related to occupational therapy practitioners’ job satisfaction?

Material and methods

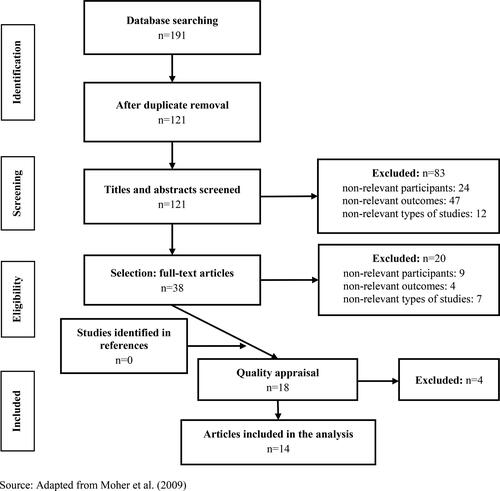

A systematic review of original quantitative studies was conducted according to the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guideline (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). The study was reported using Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA 2009 Checklist) (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Search strategy

The database search was performed in three steps (see ). First, with the help of an information specialist, keywords and index terms were identified from the PubMed and CINAHL databases in December 2019. Index terms and keywords were divided into two groups: participants and outcome. The second step included a search performed in four databases—CINAHL (EBSCO), MEDLINE (via PubMed), Scopus, and the Finnish database Medic—in which the search terms were first separated, and later combined, in January 2020 (). Gray literature was not included in this review to ensure the quality of the selected studies. Third, the references of articles selected based on full-text screening were manually searched to identify any relevant studies which may have not been identified during the second step.

Figure 1. PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process.

Source: Adapted from Moher et al. (2009).

Table 1. Search terms and results, presented according to database.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion and exclusion criteria were defined according to the PICO principles (population, intervention, comparator, outcome) and type of studies () (Tufanaru et al., Citation2020). Participants included both occupational therapists and occupational therapy assistants/technicians. Occupational therapy assistants, working under the direction of occupational therapists, were included in the review because they work closely with occupational therapists to provide occupational therapy (Bureau of Labor, U.S. Department of Labor, Citation2020). Only quantitative findings from the original studies were incorporated because the present review aimed to measure job satisfaction levels and identify the associated factors. Articles published in English or Finnish and published in peer-reviewed scientific journals in 2010–2019 would be considered. Research published during this time period was likely to be influenced by theories that consider the complex holistic nature of an occupation and place emphasis on social participation (Cole & Tufano, 2020). Humanism in the implementation of occupational therapy was perceived as important (Cole & Tufano, Citation2020; WFOT, Citation2010) and has been found to affect job satisfaction (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011).

Table 2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria, formulated according to PICO elements.

Screening process and quality assessment

After the removal of duplicates, two independent researchers (SMM, SKL) screened the studies based on inclusion and exclusion criteria. The researchers first worked separately and then reached a consensus at each step of the screening process. The process included the review of titles and abstracts, as well as full-text articles. No intervention studies (randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies) were identified, so one PICO principle, intervention, was not considered in the selection of studies. The screening process is shown in . Refworks and Microsoft Word were used to manage records and data.

The quality appraisal of the identified studies was performed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI) (Moola et al., Citation2020) ( and 4). This task was performed by two researchers (SMM, SKL), first separately and then through discussion to reach a consensus. Two additional researchers were consulted whenever consensus was not attained. A study had to receive more than 50% of the maximum score to be included in the review.

Table 3. Quality assessment of selected full-text studies using the Joanna Briggs Institute Meta-Analysis of Statistics Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-MAStARI).

Data extraction and analysis

Relevant data (i.e., results related to the research questions) were extracted from the 14 studies (Munn et al., Citation2014). The extracted data included author(s), year, country of origin, purpose, participants, methodology (study design, data collection, and data analysis), main results (Munn et al., Citation2014) and quality assessment score () (Tufanaru et al., Citation2020).

Table 4. Data extracted from the selected original studies along with the respective quality assessment scores.

Meta-analysis was not performed due to the heterogeneity of the studies (Munn et al., Citation2014). Studies were analyzed using a narrative synthesis to describe the job satisfaction among occupational therapists. A narrative synthesis analyzes the findings from multiple studies to summarize and explain the findings (Popay et al., Citation2006). The analysis included textual descriptions of the studies as well as the transformation of the reported levels of job satisfaction into a comparable format (CRD, Citation2009; Popay et al., Citation2006). The data were also categorized according to the research questions. The Percent of Maximum Possible (POMP) scoring method (Cohen et al., Citation1999), along with total POMP scores of the participants in the selected studies, weighted by sample size, were used to transform reported job satisfaction into a comparable format. The POMP score was calculated as follows: (mean-minimum score) divided by (maximum score-minimum score) multiplied by 100% (Cohen et al., Citation1999). The results were reported narratively and supplemented by tables (Munn et al., Citation2014).

Results

Search outcomes and quality appraisal

The search outcomes are outlined in using a PRISMA flow-diagram (Moher et al., 2009). Database search found 191 citations. In the screening process, the most common reason for excluding studies was non-relevant outcomes. Moreover, in several removed studies, the results of occupational therapy practitioners were not reported separately when the study also included other occupational groups. After the screening process the quality of 18 studies was assessed. Four studies were rejected based on the assessment (Abendstern et al., Citation2017; Abu Tariah, Abu-Dahab, et al., Citation2011; Parkinson et al., Citation2015; Shi & Howe, Citation2016) because of an insufficient description of the study setting, a lack of strategies to deal with the effects of confounding factors, or invalid and/or unreliable measurements. A total of 14 studies passed the quality assessment and were included in the review. The effects of confounding factors were not explicitly stated in most of the selected studies (Chen et al., Citation2012; Hammill et al., Citation2017; Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017; O’Connell & McKay, 2010; Öhman et al., Citation2017; Quick et al., Citation2010; Scanlan et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013; Souza et al., Citation2018).

Description of studies

Most studies were conducted in Australia. Participants in the studies worked in mental health (O’Connell & McKay, 2010; Scanlan et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) or several areas of health care (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018; Hammill et al., Citation2017; McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017; Souza et al., Citation2018). Some of studies did not report the nature of the health service (Chen et al., Citation2012; Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; Öhman et al., Citation2017; Quick et al., Citation2010). Participants mainly worked in the public sector (Hammill et al., Citation2017; O’Connell & McKay, 2010; Quick et al., Citation2010; Scanlan et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013; Souza et al., Citation2018), while one of the identified studies described occupational therapists working only in the private sector (Chen et al., Citation2012). However, some studies did not report the sector in which the participants worked (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018; Devery et al., Citation2018; Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017; Öhman et al., Citation2017).

Job satisfaction was measured by the Job Satisfaction Survey (Chen et al., Citation2012), single-item measures (Devery et al., Citation2018; Scanlan et al., Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013), and the Norwegian Self-Assessment of Modes Questionnaire (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018). Seven studies did not name instruments that was used to measure job satisfaction. However, the instruments were clearly described (Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017; O’Connell & McKay, 2010; Öhman et al., Citation2017; Quick et al., Citation2010; Scanlan et al., Citation2010; Souza et al., Citation2018).

Level of job satisfaction

The mean value of the rescaled job satisfaction scores for occupational therapists was 75.7 points, with scores ranging from 65.0 to 87.5 points (). Hence, the occupational therapists participating in the reviewed studies are relatively satisfied with their jobs. Authors of the studies specified that occupational therapists (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018; Devery et al., Citation2018; Scanlan et al., Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) or most occupational therapists (McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017), show high levels of job satisfaction. On the other hand, some occupational therapists were moderately satisfied (Chen et al., Citation2012; McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017; Scanlan et al., Citation2010). When only mental health services are considered, job satisfaction was also high, with a mean total weighted POMP score of 71.4 points (Scanlan et al., Citation2013; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). Most of the occupational therapists in psychiatric care were moderately satisfied or very satisfied with their current position at work (Scanlan et al., Citation2010).

Table 5. Reported mean values (along with the associated standard deviations (SD)) and weighted Percent of Maximum Possible (POMP) scores of job satisfaction.

Occupational therapists (Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; Souza et al., Citation2018) and occupational therapy assistants (Maxim & Rice, Citation2017) were satisfied with professional choice. Occupational therapists were satisfied with the nature of their work (Chen et al., Citation2012), professional role (Quick et al., Citation2010), work opportunities for their profession (O’Connell & McKay, 2010), and the material and working conditions and infrastructure (Souza et al., Citation2018). Satisfaction with pay and promotion (Chen et al., Citation2012) and professional development opportunities (Scanlan et al., Citation2010) was moderate, while satisfaction with coworkers, communication (Chen et al., Citation2012), and supervision (Chen et al., Citation2012; O’Connell & McKay, 2010; Scanlan et al., Citation2010) ranged from moderate to high. Occupational therapists were moderately satisfied with fringe benefits and dissatisfied with operating conditions (Chen et al., Citation2012).

Factors related to job satisfaction

The identified studies evaluated the associations between job satisfaction and intra-, inter-, or extra-personal factors.

Intra-personal factors

The identified studies reported contrasting results when job satisfaction among occupational therapists and other health care professionals was compared (Chen et al., Citation2012; Öhman et al., Citation2017). One study reported significant differences in job satisfaction between occupational therapists, nurses, physiotherapists, optometrists, medical imaging practitioners, medical laboratory technologists, environmental health officers, nutritionists, and dieticians (Chen et al., Citation2012), whereas other research did not detect significant differences in job satisfaction between occupational therapists, nurses and physiotherapists (Öhman et al., Citation2017). Gender was not found to be related to job satisfaction among occupational therapists (Maxim & Rice, Citation2017; Öhman et al., Citation2017) and occupational therapy assistants (Maxim & Rice, Citation2017).

Factors that contributed to job satisfaction included good clinical skills, continuing education (McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017), perceived rewards in terms of personal satisfaction, and effort (skills and energy) (Scanlan et al., Citation2013). The identified studies reported contrasting results concerning the relationship between job satisfaction and job identity. One study reported a significant positive association between these aspects (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019) while other study did not find any clear relationship between them (Devery et al., Citation2018). No significant relationship between job challenges and job satisfaction was found, which included occupational therapists’ perceptions of the effectiveness of occupational therapy and their own challenges (Devery et al., Citation2018).

Job satisfaction among occupational therapists working in mental health was related to two dimensions of burnout (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). A somewhat stronger association was detected between lower disengagement and higher job satisfaction than between lower exhaustion and higher job satisfaction in the two cited studies (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) for both relationships. On the other hand, the associations between job satisfaction, exhaustion, and disengagement did not reach statistical significance for occupational therapists working in eating disorder services (Devery et al., Citation2018).

Turnover intention is significantly negatively associated with job satisfaction in the two cited studies (Scanlan et al., Citation2013; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). Moreover, job satisfaction significantly decreased turnover intention (Scanlan et al., Citation2013) and was found to be the most common reason for why occupational therapists continue working with clients with terminal illnesses (Hammill et al., Citation2017).

Inter-personal factors

Job satisfaction was found to exert a significantly positive effect on professional relationships (McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017). However, no association between job satisfaction and job challenges related to respect from other colleagues was reported (Devery et al., Citation2018). Having a strong mentor at the beginning of one’s career was shown to positively impact job satisfaction (McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017), and there were significant relationships between higher job satisfaction, social support, and feedback (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). On the other hand, no statistically significant association between supervisor support and job satisfaction was observed (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). Occupational therapists working in elderly care differed from employees representing other settings in terms of satisfaction with supervision (Öhman et al., Citation2017), while no differences between either new graduates and experienced therapists or entry level and senior positions (Scanlan et al., Citation2010) were noted. A study from Australia revealed that satisfaction in supervision differs significantly based on an occupational therapist’s location (Scanlan et al., Citation2010). There were no statistically significant associations between the recipient contact (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) or job challenges related to co-operation and interaction with clients (Devery et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, client-relatedness (working with clients) was not associated with occupational therapists’ job satisfaction (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019).

Previous research has found that the value of therapeutic activity (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019) and the instructional approach in therapeutic relationships with clients (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018) contribute to job satisfaction among occupational therapists. Additionally, two factors concerning the meaningfulness of work, more specifically, the value of activity to clients and family and the value of activity to colleagues (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019), along with a lower degree of collaboration (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018), were found to be associated with higher job satisfaction. Instead, four therapeutic modes (i.e., advocating, empathizing, encouraging, problem-solving modes) did not significantly influence job satisfaction (Carstensen & Bonsaksen, Citation2018).

Several studies of occupational therapists in the mental health setting reported conflicting findings, namely, work-life balance was found to be positively related to job satisfaction in one study (Scanlan et al., Citation2013), whereas another report found that work-home interference does not significantly influence job satisfaction (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013).

Extra-personal factors

An employee’s level of responsibility (McCombie & Antanavage, Citation2017) and cognitive demands (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) contributed to job satisfaction. The physical environment, job hindrances (including physical workload, shift work, emotional demands), job resources (including job control, participation, job security) (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013), and job challenges (time pressure, workload (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013) were not associated to occupational therapists’ job satisfaction. High rates of client relapse, lower priority treatment, pressure to use interventions that were not specific to occupational therapy were not shown to be associated to job satisfaction (Devery et al., Citation2018).

Interestingly, McCombie and Antanavage (Citation2017) found that clearly defined roles and responsibilities were not associated with job satisfaction. There were no related factors as occupational therapists roles (therapy-specific and generic positions) (Scanlan et al., Citation2010; Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019) or healthcare settings (inpatient, community, other) (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019) or occupational therapists positions (new graduates or experienced occupational therapists, and occupational therapists in entry level or senior positions) or occupational therapists at different locations (urban or rural) (Scanlan et al., Citation2010) for job satisfaction.

Rewards, including recognition and prestige (Scanlan et al., Citation2013), as well as remuneration and recognition (Scanlan & Still, Citation2013), influence an occupational therapist’s job satisfaction. There was a statistically significant relationship between better income and benefits and higher job satisfaction (Scanlan et al., Citation2013).

Discussion

This systematic review produced novel information on job satisfaction among occupational therapy practitioners and the related factors. The identified original studies focused on different kinds of work-related aspects and these findings have been considered in the results, although the strength of the associations could not be demonstrated between job satisfaction and intra-, inter-, and extra-personal factors. However, these associations were indeed presented in the findings related to job satisfaction and different factors.

It can be stated that occupational therapy practitioners are mainly satisfied with their work in general, as well as most of aspects their work. According to previous qualitative studies reported that occupational therapists are satisfied with their work (Stickley & Hall, Citation2017), especially with regard to patient-related factors (Davey et al., Citation2014), but not satisfied with organizational factors (Davey et al., Citation2014) (e.g., salaries, limited resources) (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011). In the other studies of health care workers, it was found varying levels of job satisfaction among health care workers, ranging from dissatisfied (Nantsupawat et al., Citation2017) to relatively satisfied (Ylitörmänen et al., Citation2018) or satisfied (Arkwright et al., Citation2018; Brattig et al., Citation2014).

The opposite results were found between some professionally noteworthy intra-personal factors and job satisfaction. First, the current review revealed contrasting findings related to the association between burnout and job satisfaction. It is important to note that the one study (Devery et al., Citation2018) that did not provide evidence of such a relationship had a smaller sample size than the studies which demonstrated a significant relationship between burnout and job satisfaction (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019; Scanlan & Still, Citation2013). According to the previous reviews, burnout was significantly negatively associated with job satisfaction (Dilig-Ruiz et al., Citation2018; Friganović et al., Citation2019). Job satisfaction was especially affected by experiences of emotional exhaustion, which is one aspect of burnout (Tarcan et al., Citation2017), while the absence of burnout syndrome increased job satisfaction among health care workers (Oliveira et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, the provision of structural and social resources—both of which decrease burnout—has been shown to positively impact job satisfaction (Tims et al., Citation2012).

Second, the identified studies provided contradictory results on how employees’ perceptions of their work as an occupational therapist influence job satisfaction. However, it should be noted that the study which did not report a significant relationship between job identity and job satisfaction involved far less participants (Devery et al., Citation2018) than the study which provided evidence for a significant association between these two factors (Scanlan & Hazelton, Citation2019). Moreover, a recent meta-analysis recognized that interventions based on the development of professional identity can significantly impact job satisfaction among nurses (Niskala et al., Citation2020), while employee-specific factors, including satisfaction with work, affect professional identity (Rasmussen et al., Citation2018). This is relevant because strong professional identity increases staff retention (Rasmussen et al., Citation2018).

A significant result of the review is that higher job satisfaction was associated with, and contributed to, lower turnover intentions included in intra-personal factors. Other studies among health care professionals have shown that higher job satisfaction decreases the intention to change jobs (Bloxsome et al., Citation2019; Caers et al., Citation2008; Friganović et al., Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2019). Especially in long-term client relationships, such as in pediatric and psychiatric services, it would be important that the occupational therapist does not change frequently. The high turnover of staff can complicate the development of trust in the client-therapist relationship.

The present review revealed conflicting findings about the effects of one professionally significant inter-personal factor, client interactions, on job satisfaction. This is surprising, as numerous studies have found this factor to be highly relevant to job satisfaction among various health care professionals (e.g. Bloxsome et al., Citation2019; Lu et al., Citation2019) A client-centered approach in the implementation of occupational therapy is essential (Hammell, Citation2013; WFOT, Citation2010), though it is not always implemented in the best possible way (WFOT, 2010) due to insufficient time, organizational support, or professional autonomy (Phoenix & Vanderkaay, Citation2015). Moreover, occupational therapists have reported working with clients to be the most rewarding part of their job (Davey et al., Citation2014) and this aspect was identified as one of the main sources of job satisfaction (Abu Tariah, Hamed, et al., Citation2011; Davey et al., Citation2014).

Many of the extra-personal factors were not related to job satisfaction. However, the present review showed that various rewards were positively associated with, and influenced by, the job satisfaction of occupational therapists. This is consistent with the existing literature in that remuneration (Halcomb et al., Citation2018) and income (Scheurer et al., Citation2009; Van Ham et al., Citation2006; Zhang et al., Citation2016) influence job satisfaction among many health care professionals. As expected, based on the results of this review, recognition is also related to job satisfaction among other health care workers (Halcomb et al., Citation2018; Van Ham et al., Citation2006). When organizations take into account the specific competence of occupational therapy, occupational therapists acknowledge, value, and utilize their competencies more, which improves their job satisfaction and the delivery of therapy (Goh et al., Citation2019).

Strengths and limitations

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) guideline for systematic reviews (Aromataris & Munn, Citation2020). The fact that an information specialist supported the researchers in searching for material increased the validity of the research. The search was performed in databases that were deemed the most relevant for the research questions. Search terms were chosen based on test searches with the information specialist. Language bias may have occurred because only articles in English were identified and analyzed (Lasserson et al., Citation2019). However, English-language restriction was only used when full-text articles were assessed, with three articles rejected because of this. The risk of subjective interpretation was reduced by the involvement of two researchers in the selection and quality assessment phases (Aromataris & Pearson, Citation2014). The quality of selected studies was not taken into account during data synthesis because the review included only high-quality studies (with the lowest scoring 5/8 or 7/11 total points in the quality assessment). One weakness is that meta-analysis was not possible because the selected studies were heterogeneous with respect to each other. One limitation was that half of the selected studies did not indicate what measure had been used for job satisfaction. Also, half of the selected studies had not reported mean values of job satisfaction, so only seven studies could be considered for comparison of job satisfaction averages using weighted Percent of Maximum Possible (POMP) scores.

Implication and future research

The present review revealed how many aspects of occupational therapists’ daily work are related to job satisfaction. Future research should focus on providing statistical evidence for how various factors affect job satisfaction so that occupational therapy practitioners can maintain an adequate level of job satisfaction to promote their work well-being. More research is still required to ascertain which factors predict high job satisfaction. Future studies should also comprehensively investigate occupational therapy practitioners’ interactions with other health professionals because occupational therapy practitioners often work in multi-professional teams. Most of the studies focused on occupational therapy practitioners working in public health care. Consequently, there was only limited information about how satisfied occupational therapy practitioners working in the private sector are with their job. It would be interesting to explore in the future whether job satisfaction differs between healthcare organizations.

Most of the included studies were characterized by small or relatively small sample sizes; in this way, subsequent studies should include larger samples of health care professionals. In addition, it would be important to investigate how confounding factors affect job satisfaction. Almost all of the studies were cross-sectional, so longitudinal research and interventional studies could shed light on whether job satisfaction changes over time and clarify the effectiveness of interventions that promote job satisfaction, respectively.

The results of this review are not only relevant for the development of interventions to improve job satisfaction but also to management, as health care managers should aim to increase the job satisfaction and work well-being of their employees. Additionally, the findings could be applied to occupational therapy education (i.e., educators now have certain tools which can help guide students to reflect on internship experiences in terms of job satisfaction). It is important for employees and recent graduates to be able to identify the factors that affect job satisfaction so they can also influence these factors themselves.

Conclusion

This systematic review describes occupational therapy practitioners’ job satisfaction and the related intra-, inter-, and extra-personal factors. Findings indicate that relatively few studies have specifically focused on the job satisfaction of occupational therapy practitioners and the published research on the topic is rather heterogeneous. Furthermore, the findings of this review show that job satisfaction is a complex phenomenon, as several factors related to job satisfaction produced contradictory results. However, it is noteworthy that occupational therapy practitioners generally experience high job satisfaction.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge Margit Heikkala (information specialist, University of Oulu) for her co-operation in identifying key words and index terms, and selecting databases, as well as Hannu Vähänikkilä (statistician at University of Oulu) in transforming the data into a comparable format. This systematic review did not receive any grants from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sanna-Maria Mertala

Sanna-Maria Ruokangas is OT and MHSc. She is working as an occupational therapists in private sector in Rovaniemi in Finland. One of her interests is to study how different social work environments affect OTs’ well-being at work, such as job demands, burnout, work engagement, and job satisfaction.

Outi Kanste

Outi Kanste is RN and PhD. She is an Adjunct Professor of Health Management Science and Nursing Science in the Research Unit of Nursing Science and Health Management, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, Finland. One of her main research interests is staff wellbeing in healthcare and she has expertise in conducting systematic reviews.

Sirpa Keskitalo-Leskinen

Sirpa Keskitalo-Leskinen is RN and MHSc. She is working as an pediatric nurse in the Neonatal Intensive Care Unit in the Oulu University Hospital, Finland.

Jonna Juntunen

Jonna Juntunen is RN, MHSc and doctoral candidate. She is working as an university teacher in the Research Unit of Nursing Science and Health Management, Faculty of Medicine, University of Oulu, Finland. She is certificated in comprehensive systematic review by Joanna Briggs Institute.

Pirjo Kaakinen

Pirjo Kaakinen is RN, PhD, working as Assosiate Professor in research unit of Nursing Science and health management, University of Oulu. One of methodology focus is conduct systematic review based on JBI approach.

*All articles included in the review are marked with an asterisk in the reference list.

References

- Abendstern, M., Tucker, S., Wilberforce, M., Jasper, R., & Challis, D. (2017). Occupational therapists in community mental health teams for older people in England: Findings from a five-year research programme. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 80(1), 20–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0308022616657840

- Abu Tariah, H. S., Abu-Dahab, S. M., Hamed, R. T., AlHeresh, R. A., & Yousef, H. A. (2011). Working conditions of occupational therapists in Jordan. Occupational Therapy International, 18(4), 187–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.319

- Abu Tariah, H. S., Hamed, R. T., AlHeresh, R. A., Abu-Dahab, S. M., & Al-Oraibi, S. (2011). Factors influencing job satisfaction among Jordanian occupational therapists: A qualitative study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(6), 405–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2011.00982.x

- Arkwright, L., Edgar, S., & Debenham, J. (2018). Exploring the job satisfaction and career progression of musculoskeletal physiotherapists working in private practice in Western Australia. Musculoskeletal Science & Practice, 35(35), 67–72. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.msksp.2018.03.004

- Aromataris, E., & Munn, Z. (Eds.). (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Aromataris, E., & Pearson, A. (2014). The systematic review: An overview. The American Journal of Nursing, 114(3), 47–55. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000444496.24228.2c

- Bendixen, H. J., & Ellegård, K. (2014). Occupational therapists’ job satisfaction in a changing hospital organisation – A time-geography-based study. Work (Reading, Mass.), 47(2), 159–171. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-121572

- Bloxsome, D., Ireson, D., Doleman, G., & Bayes, S. (2019). Factors associated with midwives’ job satisfaction and intention to stay in the profession: An integrative review. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 28(3–4), 386–399. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14651

- Brattig, B., Schablon, A., Nienhaus, A., & Peters, C. (2014). Occupational accident and disease claims, work-related stress and job satisfaction of physiotherapists. Journal of Occupational Medicine and Toxicology (London, England), 9(1), 36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12995-014-0036-3

- Brown, C. A., Schell, J., & Pashniak, L. M. (2017). Occupational therapists’ experience of workplace fatigue: Issues and action. Work (Reading, Mass.), 57(3), 517–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172576

- Bruschini, M., Carli, A., & Burla, F. (2018). Burnout and work-related stress in Italian rehabilitation professionals: A comparison of physiotherapists, speech therapists and occupational therapists. Work (Reading, Mass.), 59(1), 121–129. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3233/WOR-172657

- Bureau of Labor, U.S. Department of Labor. (2020, October 25). Occupational outlook handbook, occupational therapy assistants and aides. Bureau of Labor Statistics. https://www.bls.gov/ooh/healthcare/occupational-therapy-assistants-and-aides.htm

- Caers, R., Du Bois, C., Jegers, M., De Gieter, S., De Cooman, R., & Pepermans, R. (2008). Measuring community nurses’ job satisfaction: Literature review. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(5), 521–529. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04620.x

- *Carstensen, T., & Bonsaksen, T. (2018). Factors associated with therapeutic approaches among Norwegian occupational therapists: An exploratory study. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 34(1), 75–85. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1383220

- Carter, N. T., Lowery, M. R., Williamson Smith, R., Conley, K. M., Harris, A. M., Listyg, B., Maupin, C. K., King, R. T., & Carter, D. R. (2020). Understanding job satisfaction in the causal attitude network (CAN) model. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 105(9), 959–993. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000469

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). (2009). Systematic reviews: CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in health care. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York.

- *Chen, A.-H., Jaafar, S. N., & Noor, A. R. (2012). Comparison of job satisfaction among eight health care professions in private (non-government) settings. The Malaysian Journal of Medical Sciences: MJMS, 19(2), 19–26.

- Cohen, P., Cohen, J., Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1999). The problem of units and the circumstance for POMP. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 343(3), 315–346. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327906MBR3403_2

- Cole, M. B., & Tufano, R. (2020). Applied theories in occupational therapy – A practical approach (2nd ed.). SLACK Incorporated.

- Dalege, J., Borsboom, D., van Harreveld, F., van den Berg, H., Conner, M., & van der Maas, H. L. (2016). Toward a formalized account of attitudes: The Causal Attitude Network (CAN) model. Psychological Review, 123(1), 2–22. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039802

- Davey, A., Arcelus, J., & Munir, F. (2014). Work demands, social support, and job satisfaction in eating disorder inpatient settings: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 60–68. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12014

- Derakhshanrad, S. A., Piven, E., & Zeynalzadeh Ghoochani, B. (2019). The relationships between problem-solving, creativity, and job burnout in Iranian occupational therapists. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 33(4), 365–380. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2019.1639098

- *Devery, H., Scanlan, J. N., & Ross, J. (2018). Factors associated with professional identity, job satisfaction and burnout for occupational therapists working in eating disorders: A mixed methods study. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 65(6), 523–532. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12503

- Devonish, D. (2018). Effort-reward imbalance at work: The role of job satisfaction. Personnel Review, 47(2), 319–333. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-08-2016-0218

- Dilig-Ruiz, A., MacDonald, I., Demery Varin, M., Vandyk, A., Graham, I. D., & Squires, J. E. (2018). Job satisfaction among critical care nurses: A systematic review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 88, 123–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.08.014

- Escudero-Escudero, A. C., Segura-Fragoso, A., & Cantero-Garlito, P. A. (2020). Burnout syndrome in occupational therapists in Spain: Prevalence and risk factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3164. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093164

- Friganović, A., Selič, P., Ilić, B., & Sedić, B. (2019). Stress and burnout syndrome and their associations with coping and job satisfaction in critical care nurses: A literature review. Psychiatria Danubina, 31(Suppl. 1), 21–31.

- Goh, N. C., Hancock, N., Honey, A., & Scanlan, J. N. (2019). Thriving in an expanding service landscape: Experiences of occupational therapists working in generic mental health roles within non-government organisations in Australia. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(6), 753–762. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12616

- Halcomb, E., Smyth, E., & McInnes, S. (2018). Job satisfaction and career intentions of registered nurses in primary health care: An integrative review. BMC Family Practice, 19(1), 136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0819-1

- Hammell, K. R. (2013). Client-centred practice in occupational therapy: Critical reflections. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 20(3), 174–181. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2012.752032

- *Hammill, K., Bye, R., & Cook, C. (2017). Workforce profile of Australian occupational therapists working with people who are terminally ill. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 64(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12325

- Hayes, B., Bonner, A., & Pryor, J. (2010). Factors contributing to nurse job satisfaction in the acute hospital setting: A review of recent literature. Journal of Nursing Management, 18(7), 804–814. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2834.2010.01131.x

- Herzberg, F., Mausner, B., & Snyderman, B. B. (2010). The motivation to work (12th ed.). Transaction Publishers.

- Highhouse, S., & Becker, A. S. (1993). Facet measures and global job satisfaction. Journal of Business and Psychology, 8(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02230397

- Karasek, R. (1979). Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: Implications for job redesign. Administrative Science Quarterly, 24(2), 285–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392498

- Karasek, R., & Theorell, T. (1990). Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books.

- Kaya, A., & Boz, İ. (2019). The development of the professional values model in nursing. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 914–923. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017730685

- Khan, A. S., Khan, S., Nawaz, A., & Qureshi, Q. A. (2010). Theories of job satisfaction: Global applications & limitations. Gomal University Journal of Research, 26(2), 45–62.

- Kim, J.-H., Kim, A.-R., Kim, M.-G., Kim, C.-H., Lee, K.-H., Park, D., & Hwang, J.-M. (2020). Burnout syndrome and work-related stress in physical and occupational therapists working in different types of hospitals: Which group is the most vulnerable?International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(14), 5001. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17145001

- Lasserson, T., Thomas, J., & Higgins, J. (2019). Starting a review. In J. Higgins & J. Thomas (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current

- Liu, Y., Aungsuroch, Y., & Yunibhand, J. (2016). Job satisfaction in nursing: A concept analysis study. International Nursing Review, 63(1), 84–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12215

- Locke, E. A., & Latham, G. P. (2002). Building a practically useful theory of goal setting and task motivation: A 35-year odyssey. American Psychologist, 57(9), 705–717.

- Lu, H., Zhao, Y., & While, A. (2019). Job satisfaction among hospital nurses: A literature review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 94, 21–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.01.011

- *Maxim, A. J., & Rice, M. S. (2017). Men in occupational therapy: Issues, factors, and perceptions. American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 72(1), 7201205050p1–7201205050p7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2018.025593

- *McCombie, R. P., & Antanavage, M. E. (2017). Transitioning from occupational therapy student to practicing occupational therapist: First year of employment. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 31(2), 126–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2017.1307480

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetc, R., Currie, M., Lisy, K., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., & Mu, P.-F. (2020). Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., & Aromataris, E. (2014). Data extraction and synthesis. AJN, American Journal of Nursing, 114(7), 49–54. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000451683.66447.89

- Nantsupawat, A., Kunaviktikul, W., Nantsupawat, R., Wichaikhum, O.-A., Thienthong, H., & Poghosyan, L. (2017). Effects of nurse work environment on job dissatisfaction, burnout, intention to leave. International Nursing Review, 64(1), 91–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12342

- Niskala, J., Kanste, O., Tomietto, M., Miettunen, J., Tuomikoski, A.-M., Kyngäs, H., & Mikkonen, K. (2020). Interventions to improve nurses’ job satisfaction: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1498–1508. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14342

- *O’Connell, J. E., & McKay, E. A. (2010). Profile, practice and perspectives of occupational therapists in community mental health teams in Ireland. British Journal of Occupational Therapy, 73(5), 219–228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4276/030802210X12734991664228

- *Öhman, A., Keisu, B.-I., & Enberg, B. (2017). Team social cohesion, professionalism, and patient-centeredness: Gendered care work, with special reference to elderly care - A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2326-9

- Oliveira, A. M., Silva, M. T., Galvão, T. F., & Lopes, L. C. (2018). The relationship between job satisfaction, burnout syndrome and depressive symptoms: An analysis of professionals in a teaching hospital in Brazil. Medicine, 97(49), e13364. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/MD.0000000000013364

- Parkinson, S., di Bona, L., Fletcher, N., Vecsey, T., & Wheeler, K. (2015). Profession-specific working in mental health: Impacts for occupational therapists and service users. New Zealand Journal of Occupational Therapy, 62(2), 55–66.

- Phoenix, M., & Vanderkaay, S. (2015). Client-centred occupational therapy with children: A critical perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 22(4), 318–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/11038128.2015.1011690

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews: A product of the ESRC methods programme (version I). University of Lancaster.

- *Quick, L., Harman, S., Morgan, S., & Stagnitti, K. (2010). Scope of practice of occupational therapists working in Victorian community health settings. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57(2), 95–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00827.x

- Rasmussen, P., Henderson, A., Andrew, N., & Conroy, T. (2018). Factors influencing registered nurses’ perceptions of their professional identity: An integrative literature review. Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 49(5), 225–232. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3928/00220124-20180417-08

- Reis, H. I., Vale, C., Camacho, C., Estrela, C., & Dixe, M. D. (2018). Burnout among occupational therapists in Portugal: A study of specific factors. Occupational Therapy in Health Care, 32(3), 275–289. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07380577.2018.1497244

- *Scanlan, J. N., & Hazelton, T. (2019). Relationships between job satisfaction, burnout, professional identity and meaningfulness of work activities for occupational therapists working in mental health. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(5), 581–590. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12596

- *Scanlan, J. N., Meredith, P., & Poulsen, A. A. (2013). Enhancing retention of occupational therapists working in mental health: Relationships between wellbeing at work and turnover intention. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(6), 395–403. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12074

- *Scanlan, J. N., & Still, M. (2013). Job satisfaction, burnout and turnover intention in occupational therapists working in mental health. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 60(5), 310–318. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12067

- *Scanlan, J. N., Still, M., Stewart, K., & Croaker, J. (2010). Recruitment and retention issues for occupational therapists in mental health: Balancing the pull and the push. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 57(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2009.00814.x

- Scheurer, D., McKean, S., Miller, J., & Wetterneck, T. (2009). U.S. physician satisfaction: A systematic review. Journal of Hospital Medicine, 4(9), 560–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.496

- Seah, C. H., Mackenzie, L., & Gamble, J. (2011). Transition of graduates of the Master of Occupational Therapy to practice. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 58(2), 103–110. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1630.2010.00899.x

- Shi, Y., & Howe, T.-H. (2016). A survey of occupational therapy practice in Beijing, China. Occupational Therapy International, 23(2), 186–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/oti.1423

- Siegrist, J. (1996). Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1(1), 27–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//1076-8998.1.1.27

- Spector, P. E. (1997). Job satisfaction: Application, assessment, causes, and consequences. SAGE Publications, Inc.

- *Souza, A. M., da Silva Santos, R., Genezini, R. S., & do Amaral, M. F. (2018). Characterization of occupational therapy’s labor market in Sergipe State. Brazilian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 26(4), 739–746. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.4322/2526-8910.ctoAO1256

- Stickley, A. J., & Hall, K. J. (2017). Social enterprise: A model of recovery and social inclusion for occupational therapy practice in the UK. Mental Health and Social Inclusion, 21(2), 91–101. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/MHSI-01-2017-0002

- Tarcan, M., Hikmet, N., Schooley, B., Top, M., & Tarcan, G. Y. (2017). An analysis of the relationship between burnout, socio-demographic and workplace factors and job satisfaction among emergency department health professionals. Applied Nursing Research: ANR, 34, 40–47. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2017.02.011

- Tims, M., Bakker, A. B., & Derks, D. (2012). The development and validation of the Job Crafting Scale. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 80(1), 173–186. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.009

- Tufanaru, C., Munn, Z., Aromataris, E., Campbell, J., & Hopp, L. (2020). Chapter 3: Systematic reviews of effectiveness. In E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI manual for evidence synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute. https://synthesismanual.jbi.global

- Turner, N., Barling, J., & Zacharatos, A. (2002). Positive psychology at work. In C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez, Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 715–728). Oxford University Press.

- Van Ham, I., Verhoeven, A. A., Groenier, K. H., Groothoff, J. W., & De Haan, J. (2006). Job satisfaction among general practitioners: A systematic literature review. European Journal of General Practice, 12(4), 174–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13814780600994376

- World Federation of Occupational Therapists (WFOT). (2010). Position statement - Client-centredness in occupational therapy.World Federation of Occupational Therapists.

- World Health Organization (WHO). (2016). Global strategy on human resources for health: Workforce 2030. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/250368/9789241511131-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- Ylitörmänen, T., Turunen, H., & Kvist, T. (2018). Effects of nurse work environment on job dissatisfaction, burnout, intention to leave. Journal of Nursing Management, 26(7), 888–897. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12620

- Zhang, M., Yang, R., Wang, W., Gillespie, J., Clarke, S., & Yan, F. (2016). Job satisfaction of urban community health workers after the 2009 healthcare reform in China: A systematic review. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 28(1), 14–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzv111