Abstract

Research coursework can be challenging for occupational therapy students, thus potentially compromising their engagement in learning. A student engagement framework was used to design and implement an innovative assignment called Researchers’ Theater with a cohort of 38 first-semester occupational therapy students. At the beginning of each class, a small group of students led a creative activity to review topics from the preceding week. Student feedback survey results and instructors’ observations suggest this framework contributed to students’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement. Findings also highlight the potential value of student-led, game-based learning for reinforcing course content.

Background

Entry-level occupational therapy students in the United States need to acquire basic knowledge about research (Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education, Citation2023). Students have reported that they regard research as an important aspect of occupational therapy education, are motivated to learn about it, and feel positively about the integration of research into their coursework (Helgøy et al., Citation2020; Sargent et al., Citation2020; Valdes et al., Citation2020). However, some students have experienced difficulty with research concepts, such as interpretating statistics (DeCleene Huber et al., Citation2015). Occupational therapy educators have even observed student annoyance or dislike toward research evidence due to its complexity (Hallé et al., Citation2021).

At Samuel Merritt University in the Western United States, multiple cohorts of entry-level occupational therapy students had anecdotally reported their introductory research course to be challenging. This course introduces first-semester Master’s and Doctoral students to research methods, evidence-based practice, and scientific writing. I was the lead instructor for this course, and a co-instructor participated during four weeks of the semester. Given students’ reported feelings of anxiety and intimidation associated with this course, there seemed to be a need for students to engage with the course content in a more fun and relaxed manner. Researchers’ Theater was created to meet this student need.

Innovation

Researchers’ Theater was conceptualized as creative, student-led activities that would reinforce course content while promoting student engagement. Student engagement has become an important indicator of institutional success in higher education (Groccia, Citation2018) and specifically within health professions education (Kassab et al., Citation2023). Kassab et al. (Citation2023) defined student engagement as a student’s investment of time and energy in learning-related activities. Engagement is a complex construct that comprises three dimensions: affective, behavioral, and cognitive (Wong et al., Citation2024). Affective engagement (how students are feeling) includes levels of interest, motivation, confidence, and self-efficacy. Behavioral engagement (what students are doing) encompasses the learner’s observable actions such as attendance, assignment completion, and classroom participation. Cognitive engagement (how students are thinking) pertains to students’ mental investment in the learning process and the degree to which they are thinking deeply and reflecting on their learning (Luo, Citation2022). All three dimensions correlate with academic achievement, student well-being, and student retention (Kassab et al., Citation2023; Wong et al., Citation2024). The three-dimension engagement theory (Luo, Citation2022) served as a guiding framework for the assignment design and outcome assessment of Researchers’ Theater.

This project was deemed as exempt by Samuel Merritt University’s Institutional Review Board. Researchers’ Theater was piloted with a class of 38 students; 28 were doctoral students and 10 were master’s students with assignment requirements being the same for both levels of students. The purpose of the Researchers’ Theater assignment was communicated to students as: to provide a fun, creative way for students to review and reinforce course content. At the start of the semester, students were randomly assigned to work together in “theater groups” of three to four people and were provided a schedule of their respective presentation dates. Each group chose its specific topic(s) from course content covered during the week preceding its theater performance. The deliverable was communicated to students as: a 5- to 10-minute activity for the class such as a skit, a musical/dance performance, a viewing/explanation of artwork, or a game involving audience members. All group members must participate in delivering the activity. The theater season opened during the second week of class, with one group presenting at the beginning of each class. Each group presented once. At least one day prior to the scheduled theater presentations, each group submitted a written Researchers’ Theater Summary (provided in the Resources section of this paper), designed as a project planning and faculty oversight tool. Researchers’ Theater was created as a low-stakes assignment, worth 1.5% of the total course grade. summarizes Researchers’ Theater’s key design elements, their correspondence to student engagement, and supporting evidence from the literature.

Table 1. Assignment design elements and their correspondence to student engagement.

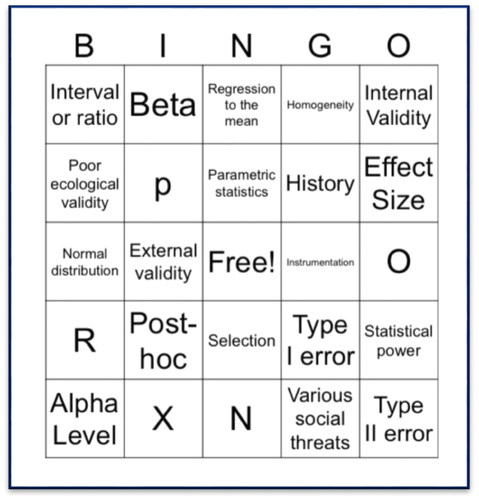

Eleven total Researchers’ Theater sessions were implemented, and all theater groups chose activities requiring audience members to answer quiz questions. Two sessions involved individual completion of a worksheet, while nine of the sessions incorporated a competitive game. The media used for the competitive individual or group games included digital apps such as Kahoot, Jeopardy, or Quizlet; a game board drawn on the classroom white board and magnets for game pieces; and student-created paper Bingo cards. A sample Bingo card is provided in . Three theater groups incorporated physical activities and movement; these involved throwing a wad of paper into a basket, competing in a rock paper scissors tournament, and running up to hit a pretend buzzer (a stapler) faster than the other team. All students in the course received full credit for the Researchers’ Theater assignment.

Figure 1. A Bingo game card created by a Researchers’ Theater group.

Note. During a Researchers’ Theater, each audience member was provided a Bingo game card, similar to the one in this figure. A presenter would verbalize a description of a research concept, audience members would attempt to answer, and then all audience members who knew the correct answer (by honor system) would mark the corresponding square on their game cards. This image is used with the creators’ permission.

Outcomes

Student Feedback Survey

The primary method for assessing the impact of Researchers’ Theater was an anonymous online student feedback survey administered at the end of the semester. Survey content was based on the three-dimension engagement theory (Luo, Citation2022). To assess affective engagement, students were asked whether Researchers’ Theater was fun and whether the activities felt like the right level of challenge. Behavioral engagement was examined by asking whether Researchers’ Theater elicited the learners’ active participation. Cognitive engagement was addressed by asking about their learning process and understanding of concepts. Additionally, the survey asked whether Researchers’ Theater should be continued in the future. Lastly, the survey included three text-entry questions: 1) What worked well with Researchers’ Theater, 2) How could Researchers’ Theater be improved, and 3) Any additional comments.

The response rate was 89%, with 34 responses received from a class of 38 students. As depicted in , an overwhelming majority of respondents indicated agreement with all seven Likert scale items. All respondents (100%) recommended continuing with Researchers’ Theater for future cohorts.

Table 2. Student Feedback Survey results for likert scale items.

Analysis of the 69 narrative responses yielded an overarching perspective of: intersection of fun and learning. Multiple respondents reported that Researchers’ Theater was a fun way to learn, or that they were having fun while learning. One respondent explained that Researchers’ Theater “created space for appropriate fun/goofiness while learning.” Students expressed positive feedback about this new structure, which seemed to support their learning process.

Positive feedback

Many respondents reported Researchers’ Theater to be enjoyable and engaging. One respondent stated, “Researchers’ Theater is one of my favorite elements of this class.”

Another respondent explained that Researchers’ Theater had “engaging activities that made me want to participate.” The opportunities for active participation, peer interactions, and games seemed to contribute to participants’ positive emotional responses. One respondent reported, “I really enjoyed participating in fun activities with my classmates!” Another respondent highlighted that Researcher’s Theater “got people moving.”

Respondents liked that Researchers’ Theater was student-led and valued the creativity of the activities. Furthermore, several respondents reportedly appreciated the low-stakes aspect of Researchers’ Theater. One respondent noted, “Having the assignment be low stakes helped me take a more creative approach to this.” Another reported, “Doing a low-stakes review was a good opportunity to review without having anxiety about getting a bad grade if I make mistakes.”

Learning process

The most frequently cited learning benefit was reviewing the previous week’s content at the start of class before moving on to new content. Respondents explained that they valued the demand put on them during Researchers’ Theater to recall information, which reinforced their comprehension of concepts. Moreover, they reported that the Researchers’ Theater activities provided feedback on their current understanding and their knowledge gaps. One respondent explained, “Researchers’ Theater allowed me to understand what I know and what I need to work on for this class.” Experiencing a variety of learning activities during Researchers’ Theater seemed to also help students with learning course content. One respondent reflected that there were “various learning styles and ways to access the material.” Additionally, respondents suggested that a compilation of content from Researchers’ Theater sessions would be a helpful study tool.

Instructors’ observations and reflections

As the lead course instructor, I observed the implementation of all 11 Researchers’ Theater sessions. Additionally, a co-instructor observed four sessions. Over the semester, I maintained notes about my observations and the co-instructor’s spontaneous comments during the weekly implementation. In review of the observational notes, a high degree of enthusiasm and a concerted effort were noted.

Enthusiasm

Both instructors observed a high level of enthusiasm among students during Researchers’ Theater. Students laughed and joked with each other. They animatedly expressed their excitement, both verbally and physically, about the outcomes of the various games. Students enthusiastically encouraged and congratulated their classmates. Researchers’ Theater activities, particularly those involving physical movement throughout the classroom, appeared to elevate the students’ energy level and alertness.

Concerted effort

During Researchers’ Theater, students carefully considered the questions posed to them. During team-based games, they engaged in thoughtful discussions by asking critical questions of each other and contemplating different viewpoints. Some students referred to class notes and course materials to search for the answers. After answers were provided, students sometimes sought additional clarification.

The level of effort put forth by the presenters exceeded the instructors’ expectations. The originality of the activities was notable, as it may have been easier to repeat an activity. Only one activity, Kahoot, was used by two different groups. Besides preparing the game questions and platforms, several groups provided prizes. One group even planned background music to help “set the mood” for their theater presentation.

Implications for occupational therapy education

The outcomes suggest that Researchers’ Theater supported students’ affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement. The findings from this pilot project suggest several implications for occupational therapy education as summarized below.

Adopt a student engagement framework. Student engagement is an important consideration for curriculum design and outcome assessment, particularly for topics that students may perceive as challenging. The three-dimension (affective, behavioral, and cognitive) conceptualization of student engagement (Luo, Citation2022; Wong et al., Citation2024) may be a useful framework for occupational therapy educators when designing and evaluating curriculum.

Leverage low-stakes assignments. As demonstrated in this project, low-stakes assignments have been shown to increase student engagement, satisfaction, confidence, and performance as well as reduce anxiety (Beam, Citation2021; Meer & Chapman, Citation2014; Schrank, Citation2016; Stewart-Mailhiot, Citation2014). Low-stakes assignments may be most effective when offered early and frequently during the academic semester (Meer & Chapman, Citation2014; Schrank, Citation2016) as was the case with Researchers’ Theater.

Student-led learning activities may bolster accessibility of the learning experience. Student feedback suggests that student-led activities of Researchers’ Theater provided multiple ways for learners to interact with course content. This phenomenon may exemplify Universal Design for Learning framework, which acknowledges the diversity of learner attributes and focuses on creating flexible and accessible experiences for all (Bray et al., Citation2023). The diverse activities and varied modes of presentation during Researchers’ Theater align with the three Universal Design for Learning principles: multiple means of engagement, multiple means of representation, and multiple means of action and expression (Bray et al., Citation2023).

Create opportunities for retrieval practice. Survey results highlight that the demand put on students during Researchers’ Theater to recall information reinforced their comprehension. Researchers’ Theater’s trivia question activities likely benefited the students’ cognitive engagement and learning through retrieval practice. Retrieval practice is any activity that requires a learner to recall previously learned information and has been shown to be more effective for long-term retention than simply re-reading or re-exposure to the content (Latimier et al., Citation2021).

Explore game-based learning. Although students were offered a broad range of options for their Researchers’ Theater activity, the overwhelming majority chose a game-based activity. Within occupational therapy education, game-based learning has been described as the use of digital or traditional games to support learning (Booker & Mitchell, Citation2021; Myers, Citation2020; Sáiz-Manzanares et al., Citation2021). Students’ positive responses to playing interactive games during Researcher’s Theater seem to support the potential value of game-based learning in occupational therapy education as documented in the literature (Booker & Mitchell, Citation2021; Martín-Hernández et al., Citation2021).

Additional resources

Prompts for the Researchers’ Theater summary assignment

List the names of your group members.

Which topic will you be addressing?

State in 1-2 sentences the specific concept(s) or information you will review through your planned theater.

If you plan to use quiz question, provide a copy of the questions.

Grading rubric for the Researchers’ Theater assignment

Recommended reading about the construct of student engagement and its application in higher education

Groccia, J. E. (2018). What is student engagement? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 154, 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20287

Recommended reading about outcome measures for student engagement in health professions education

Kassab, S. E., Al-Eraky, M., El-Sayed, W., Hamdy, H., & Schmidt, H. (2023). Measurement of student engagement in health professions education: A review of literature. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04344-8

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Robyn Wu

Robyn Wu is an Associate Professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy at Samuel Merritt University in Oakland, CA, USA.

References

- Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (2023). 2023 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) standards and interpretive guide. https://acoteonline.org/accreditation-explained/standards/

- Beam, E. A. (2021). Leveraging outside readings and low-stakes writing assignments to promote student engagement in an economic development course. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(4), 274–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2021.1963369

- Booker, K. L., & Mitchell, A. W. (2021). From boring to board game: The Effect of a serious game on key learning outcomes. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 5(4), 7. https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2021.050407

- Bray, A., Devitt, A., Banks, J., Sanchez Fuentes, S., Sandoval, M., Riviou, K., Darren, B., Flood, M., Reale, J., & Terrenzio, S. (2023). What next for universal design for learning? A systematic literature review of technology in UDL implementations at second level. British Journal of Educational Technology, 55(1), 113–138. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13328

- Ciarocco, N. J., Lewandowski, G. W., Jr., & Van Volkom, M. (2013). The impact of a multifaceted approach to teaching research methods on students’ attitudes. Teaching of Psychology, 40(1), 20–25. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628312465859

- DeCleene Huber, K. E., Nichols, A., Bowman, K., Hershberger, J., Marquis, J., Murphy, T., Pierce, C., & Sanders, C. (2015). The correlation between confidence and knowledge of evidence-based practice among occupational therapy students. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 3(1), Article 5. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1142

- Dennis, D., Furness, A., Brosky, J., Owens, J., & Mackintosh, S. (2020). Can student-peers teach using simulated-based learning as well as faculty: A non-equivalent posttest-only study. Nurse Education Today, 91, 104470. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2020.104470

- Donham, C., Pohan, C., Menke, E., & Kranzfelder, P. (2022). Increasing student engagement through course attributes, community, and classroom technology: Lessons from the pandemic. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 23(1), e00268-21. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.00268-21

- Ghani, S., & Taylor, M. (2021). Blended learning as a vehicle for increasing student engagement. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2021(167), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20458

- Groccia, J. E. (2018). What is student engagement? New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2018(154), 11–20. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.20287

- Hallé, M.-C., Bussières, A., Asseraf-Pasin, L., Storr, C., Mak, S., Root, K., & Thomas, A. (2021). Building evidence-practice competencies among rehabilitation students: A qualitative exploration of faculty and preceptors’ perspectives. Advances in Health Sciences Education: Theory and Practice, 26(4), 1311–1338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10051-0

- Helgøy, K. V., Smeby, J.-C., Bonsaksen, T., & Rydland Olsen, N. (2020). Research-based occupational therapy education: An exploration of students’ and faculty members’ experiences and perceptions. PloS One, 15(12), e0243544. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0243544

- Hernández Coliñir, J., Molina Gallardo, L., González Morales, D., Ibáñez Sanhueza, C., & Jerez Yañez, O. (2022). Characteristics and impacts of peer assisted learning in university studies in health science: A systematic review. Revista Clinica Espanola, 222(1), 44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rceng.2021.02.006

- Kassab, S. E., Al-Eraky, M., El-Sayed, W., Hamdy, H., & Schmidt, H. (2023). Measurement of student engagement in health professions education: A review of literature. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 354. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04344-8

- Larkin, H., & Hitch, D. (2019). Peer Assisted Study Sessions (PASS) preparing occupational therapy undergraduates for practice education: A novel application of a proven educational intervention. Australian Occupational Therapy Journal, 66(1), 100–109.https://doi.org/10.1111/1440-1630.12537

- Latimier, A., Peyre, H., & Ramus, F. (2021). A meta-analytic review of the benefit of spacing out retrieval practice episodes on retention. Educational Psychology Review, 33(3), 959–987. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-020-09572-8

- Luo, Z. (2022). Gamification for educational purposes: What are the factors contributing to varied effectiveness? Education and Information Technologies, 27(1), 891–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-021-10642-9

- Martín-Hernández, P., Gil-Lacruz, M., Gil-Lacruz, A. I., Azkue-Beteta, J. L., Lira, E. M., & Cantarero, L. (2021). Fostering university students’ engagement in teamwork and innovation behaviors through game-based learning. Sustainability, 13(24), 13573. https://doi.org/10.3390/su132413573

- Meer, N. M., & Chapman, A. (2014). Assessment for confidence: Exploring the impact that low-stakes assessment design has on student retention. The International Journal of Management Education, 12(2), 186–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2014.01.003

- Myers, E. (2020). Effect of a gamification model on a graduate level occupational therapy course. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 4(3), 6. https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2020.040306

- Sáiz-Manzanares, M. C., Martin, C. F., Alonso-Martínez, L., & Almeida, L. S. (2021). Usefulness of digital game-based learning in nursing and occupational therapy degrees: A comparative study at the University of Burgos. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(22), 11757. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182211757

- Sargent, J., Wermers, A., Russo, L., & Valdes, K. (2020). Master’s and doctoral occupational therapy students’ perceptions of research integration in their programs. The Open Journal of Occupational Therapy, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.15453/2168-6408.1614

- Schrank, Z. (2016). An assessment of student perceptions and responses to frequent low-stakes testing in introductory sociology classes. Teaching Sociology, 44(2), 118–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X15624745

- Squire, N. (2023). Undergraduate game-based student response systems: A systematic review. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 28(4), 1903–1936. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10758-023-09655-9

- Stewart-Mailhiot, A. (2014). Developing research skills with low stakes assignments. Communications in Information Literacy, 8(1), 32–42. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1089130

- Valdes, K. A., Dalton, S., Modeste, D., Moskalczyk, J. J., Olmo, T., & Smith, J. M. (2020). Student perceptions of research in an occupational therapy doctoral program: A cross-sectional survey. Journal of Occupational Therapy Education, 4(1), Article 12. https://doi.org/10.26681/jote.2020.040112

- Wong, Z. Y., Liem, G. A. D., Chan, M., & Datu, J. A. D. (2024). Student engagement and its association with academic achievement and subjective well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 116(1), 48–75. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000833