Abstract

The movement of people from and to countries and regions with different Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) prevalence and practices and the implications for the elimination of FGM are under researched. In this article, we intend to examine the factors that support or deter Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) in the context of internal, regional and international migration in and from countries in the Arab League Region. We selected the Arab League Region as the focus of this article as it contains countries with some of the highest FGM adult prevalence rates in the world, as well as countries where FGM is not traditionally performed. It is also a region with high levels of population mobility including internal, regional and international flows of migration. The region thus provides a case study, which can help elucidate other geographical migration-FGM contexts.

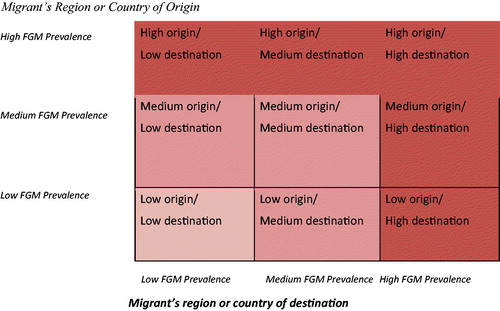

The authors undertook a rigorous literature review, which informed the development of a new theoretical framework for analyzing the effect of the migrant journey on the attitudes toward and the practice of FGM. The “FGM- Migration Matrix” illustrates the complexity of the situation and provides a framework for analyzing the intricate implications of the migrant journey on FGM decisions. Exploring the migrant journey using the matrix as a framework will enable practitioners who are working to lessen the prevalence of FGM to appreciate the social norms and pressures that migrants have been exposed to, to either stop, continue or adopt the practice of FGM. This will allow them to implement more nuanced and effective interventions that take account of not only the migrant journey, but also issues associated with integration and identity.

The authors focus on three “FGM-Migration” scenarios: migration from high prevalence regions of origin to high prevalence regions of destination;migration of non-FGM practicing groups to destinations with high FGM prevalence; and migration of FGM practicing groups to destinations with low FGM prevalence. The authors illustrate the multifaceted nature of the relationship between FGM and population mobility and demonstrate that issues such as the migrant journey, integration with host communities and importance of FGM as an identity marker require further research. In particular, studies need to be undertaken on all groups of migrants within and from the Arab League Region, such as those from Egypt, Oman, Djibouti as well as in refugee settlements in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, to ensure we understand the drivers of FGM in migration contexts.

Background

In December 2012 the United Nations General Assembly adopted a Resolution to ban Female Genital Mutilation (FGM) worldwide (A/RES/67/146). Its adoption by the international community reflected a universal agreement that FGM constitutes a violation of human rights which all countries should address through “all necessary measures, including enacting and enforcing legislation to prohibit FGM and to protect women and girls.” Since the Resolution was adopted, eliminating FGM has become a target as part of UN Sustainable Development Goal 5, which aims to achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls (United Nations, Citation2016). FGM affects over 200 million girls and women globally with an estimated 30–70 million girls under the age of 15 at risk of FGM over the next decade (Shell-Duncan et al., Citation2016; UNICEF, Citation2016). The practice is highly concentrated in thirty countries in Africa, the Middle East and South East Asia (UNICEF, Citation2016). Half of all women who have undergone FGM live in just three countries: Egypt, Ethiopia; and Indonesia (UNICEF, Citation2016). Over the last thirty years there has been a decline in FGM prevalence in many countries, but the pace of decline has been uneven (UNICEF, Citation2016). In 2016 UNICEF issued this warning to the world:

Current progress is insufficient to keep up with increasing population growth. If trends continue, the number of girls and women undergoing FGM/C will rise significantly over the next 15 years. (UNICEF, Citation2016, p. 4).

At the same time that the international community has vowed to tackle FGM the world is witnessing one of the highest displacements of people on record, an unprecedented 65.3 million forcibly displaced people worldwide, 21.3 million of whom are refugees (UNHCR, Citation2015). In 2015 the IOM (Citation2016) estimated that nearly 24 million people from the Middle East and North Africa (MENA) Region, including refugees, were living outside their country of birth. At the same time the MENA

Region hosts 39% of global displaced people followed by sub-Saharan Africa which hosted 29% (UNHCR, Citation2015). Many countries are therefore experiencing high levels of both emigration and immigration as well as internal displacement. These countries are often high FGM prevalence countries, yet the impact of population displacement both within and between countries on the practice and prevalence of FGM is little understood (IOM, Citation2009).

The aim of the authors is to examine the factors that support or deter FGM in the context of internal, regional and international migration, displacement and other humanitarian settings in and from countries in the Arab League Region. For the purposes of this article this includes all 21 members of the Arab League States (ALS) plus Syria and Iran for geographical completeness (see for full list). This region was selected for study as it contains countries and regions with diverse FGM status, as well as highly mobile populations. It thus offers insights for other regions affected by the same issues.

Table 1. FGM as a social norm in the Arab League Region (Arab League States plus Iran and Syria*).

The authors undertook a rigorous literature review and an “FGM – Migration Matrix” was devised to facilitate the analysis of the complex situations presented in the research literature for emigrants and immigrants in and from the Arab League Region. The authors provide an analysis of the linkages between culture, social norms and practices of FGM and its manifestation among groups of people who are forcibly moved (refugees and internally displaced) and those who chose to move for economic or other reasons, and their interaction with host communities, who may and may not be practicing FGM.

The Arab League Region

FGM Situation

The Arab League Region was selected as the focus of this article, as the region contains countries with some of the highest FGM adult prevalence rates in the world. It contains six countries with prevalence rates of FGM in females aged 15–49 of over 60%, which are classed by UNFPA as High Prevalence Countries (see ). These are Somalia (98%), Djibouti (93%), Egypt (87%), Sudan (87%), Eritrea (83%) and Ethiopia (74%) (UNICEF, Citation2016). By contrast, two countries in the region are classed as Low Prevalence Countries (with prevalence of less than 20% in females aged 15–49): Yemen (19%) and Iraq (8%) (UNICEF, Citation2016). However whilst the national prevalence in these countries might be low, the practice is concentrated in certain ethnic groups and geographical regions. For example in Iraq the national FGM prevalence rate is only 8% but the practice is concentrated in Kurdish northern regions consisting of three governorates (Arbil (Erbil); Suleymaniya; Garmyan; and New Kirkuk) which have a population of 5.5 million people (Burki, Citation2010). Most women in these governorates have undergone FGM with a study by researchers at WADI (Citation2010) calculating an FGM prevalence rate of 73% in these regions. Other countries in the region either have few or no cases of FGM as well as countries and regions where FGM is very rare.

In addition to a range of FGM prevalence rates across the Arab League Region, there is variation in the types of FGM performed. shows the types of FGM performed on girls and women aged 15–49 in the Arab League Region countries for which there is data. This shows that FGM Type III dominates in Djibouti and Somalia. In Djibouti, researchers at the Research Directorate, Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada (IRB, Citation2016) on FGM in the country, including among minority groups, revealed that the prevalence of FGM was the same for all the ethnic groups in Djibouti, but the type practiced varies depending on the ethnic group. Among the three communities that make up the Djiboutian population, the Arabs perform Type II and the other two communities, the Afar and the Somalis, practice Type III. The researchers demonstrate how nationality alone is not a good indicator of the type of FGM and that ethnicity must be considered (IRB, Citation2016).

Table 2. Percentage of girls and women aged 15–49 who have undergone FGM by Type and prevalence in Arab League Region countries for which data is available.

The FGM situation in the Arab League Region is clearly complex as shows. It is a mixture of high and low FGM prevalence countries with various intensity of social norms supporting the practice, ranging from countries and regions where the social norm supporting FGM is generalized, for example, Djibouti and Somalia, to those where the social norm is concentrated amongst ethnic groups or in geographical regions, such as in Northern Iraq. Then there are other countries and regions where FGM is not practiced and the social norm is not to perform FGM, as is the case in Kuwait and Qatar. In other countries such as Saudi Arabia and Jordan, FGM has been reported amongst migrant communities (DFID, Citation2013; Rouzi et al., Citation2017). This suggests that when population movements are added to the mix, the FGM situation in the Arab League Region is complex, diverse and dynamic.

A region of population movements

The Arab League Region has a history of “people on the move” with Iraq, Sudan and South Sudan being amongst the top ten countries with the largest displaced populations every year since 2003 (IDMC, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). The Syrian crisis has resulted in 4.9 million Syrian refugees, with Iraq hosting nearly 25,000 of them (UNHCR, Citation2015). Kurdistan/Iraq is a region where FGM is widely practiced, potentially putting the Syrian refugees (who do not traditionally practice FGM) at risk, due to the links between ethnicity (Kurd), law school (Shafi’i) and FGM (Geraci & Mulders, Citation2016). The movement of people from and to countries and regions with different prevalence and practices of FGM and the implications for the elimination of FGM are little known. The authors will explore the relationship between FGM and population movements in and from the Arab League Region, through existing research using the “FGM – Migration Matrix” as a framework.

Methods: rigorous evidence-based literature review

The authors undertook a rigorous evidence-based literature review based on the methodology described by Hagen-Zanker & Mallett (Citation2013). It has been designed to ensure rigor, transparency and replicability, “whilst allowing for a flexible and user friendly handling of retrieval and analysis methods” (Hagen-Zanker & Mallett, Citation2013, p. 1). Rigorous reviews allow for greater flexibility and reflexivity than systematic reviews (DFID, Citation2014; Hagen-Zanker & Mallett, Citation2013). A rigorous review includes three tracks in terms of literature retrieval: an academic literature search using standard databases in order to identify potentially relevant material; snowballing, namely actively seeking advice on relevant publications from key experts; and grey literature capture, including traditional and social media.

We carried out internet-based searches for published literature in international social and public health databases such as: Pubmed, Medline, Popline, SOSIG, Scopus, Science Direct and Google Scholar. Journal sites, such as Forced Migration Review were also examined, as well as exploring key authors and organizations of relevance, such as the UNHCR, WHO and IOM. Searches were restricted to English sources with a publication date of 2005 to present. Seminal works that predated 2005 were also included as well as relevant grey literature that met the selection criteria.

Searches were made using the following terms: Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)/Female Genital Cutting (FGC)/Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C)/Female Circumcision/Sunna and displacement/migration/refugees. This was combined with Diaspora/African diaspora/moving populations/social inclusion or exclusion/integration of refugees/displaced people/migrants/refugee camps/protection of girls in refugee camps/ethnic, cultural and religious identity.

We retrieved documents that related to at least one of the above terms/themes and one or more of the following countries: Djibouti; Egypt; Kurdistan Region of Iraq; Somalia; Sudan; Syria; and Yemen. Sources included population movements within these countries, between these countries, and from these countries to other regions e.g. to Africa, Europe and North America. Documents that did not include any authorship, year or bibliography were excluded.

The literature search revealed that the majority of research and studies focused on the prevalence of FGM amongst migrant communities and the health complications and treatment of survivors of FGM in refugee camps in Africa and those who had been resettled in the West. Most of these investigations focused on migrant populations from the Horn of Africa, in particular Somali and Sudanese communities. We found few sources where the researchers had focused on the impact of migration on the practice of FGM in the Arab League Region.

Most of the studies used in this report were qualitative in nature. As such they provide in-depth information on a very sensitive topic. However most studies used small samples and there was a lack of comparability in the methods employed. This means that caution must be used when generalizing from such studies.

Following the completion of the rigorous literature review the authors devised the FGM-Migration Matrix () to act as a framework for the analysis. The FGM – Migration Matrix illustrates the complexity of the situation concerning FGM and migration, including internal and international movements. We propose nine scenarios when referring to FGM and migration. This includes a range of situations ranging from migrants from low prevalence regions or countries settling in low prevalence destinations, through to migrants from high prevalence regions or countries settling in high prevalence destinations. The challenges occur when people migrate to regions or countries where the prevalence and culture concerning FGM is very different from their home country. At the extremes are situations where people from regions or countries where FGM prevalence is high, resettle in regions or countries where FGM prevalence is low, or vice-a-versa. In these situations the issues of integration with the destination society, identity and acculturation become serious concerns.

Figure 1. The FGM-migration matrix.

Note: Based on UNFPA Classification: Low FGM prevalence is <20% amongst 15–49 year old females: Medium FGM prevalence is 20–60% amongst 15–49 year old females: High FGM prevalence is >60% amongst 15–49 year old females. Source: Barrett.

The situation is complicated even further by the fact that migrants often settle in more than one region or country before reaching their current destination country, and these may all have different cultural and legal environments concerning FGM. What is of interest is the impact on FGM practices of migrants settling (or traveling through) regions or countries with discordant FGM situations. The Matrix can be used to track migration journeys, highlighting the effects that traveling through different scenarios could have on FGM decisions at destination.

In addition to this, whilst in exile migrants may well visit relatives in the region or country of origin, and in all probability keep in touch by phone or social media, so are exposed to the social norms relating to FGM of their region or country of origin (Barrett et al., Citation2015; IOM, Citation2009). Some migrants report being pressurized by relatives still living in the home region or country (Barrett et al., Citation2015; Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012; Gele, Johansen, et al., Citation2012). Then there is the under researched topic of the influence of the diaspora on attitudes and practices concerning FGM in home countries (IOM, Citation2009) and return migration and the impact this can have.

Results

Due to the lack of published research on each of the nine scenarios shown in the FGM-Migration Matrix in , we focus on the following three scenarios where research evidence was retrieved:

Migration from high prevalence regions of origin to high prevalence regions or countries of destination. In the context of the Arab League Region this tends to comprise internal and regional population movements, which due to political instability in parts of the region, inevitably means migrants living in refugee or IDP settlements.

Migration of non-FGM practicing groups to destination regions and countries with high FGM prevalence. In the Arab League Region this type of population movement is commonly internal migration, or regional movements. This scenario could also include return migration to areas of high FGM prevalence from low prevalence regions and countries of destination, usually in the West.

Migration of FGM practicing groups to destination regions and countries with low FGM prevalence. In terms of the Arab League Region these migration flows are usually associated with migration to Western countries in Australasia, Europe and North America.

Migration of FGM practicing groups to regions/countries with high FGM prevalence

Very few outputs retrieved for this article investigated the impact of regional population movements on the practice of FGM in the Arab League Region. Of the few studies found, most researchers had focused on refugees living in refugee settlements outside their home country, in particular in the Horn of Africa. However, there are large populations of internally displaced people in the Arab League Region, who receive less attention concerning the impact of their displacement on attitudes toward FGM. Of course this is all complicated by past and current efforts to tackle FGM in the Arab League Region which makes it difficult to determine the contribution of migration to any changes to attitudes and practice concerning FGM amongst migrants.

There are few inquiries undertaken of the prevalence and practice of FGM in refugee settlements. In February 2004 researchers undertook a cross-sectional study in three Somali refugee settlements in Somali Regional State in Eastern Ethiopia involving 492 refugee men and women as well as 26 traditional excisors. The aim of the researchers was to determine the prevalence and factors associated with the continuation or abandonment of FGM amongst Somali refugees living in these refugee settlements (Mitike & Deressa, Citation2009). The researchers found that in the three refugee settlements, FGM was undertaken on girls aged 6–8 years. Only 36% of the FGM performed was Type III indicating that infibulation was becoming less common compared to the FGM Type III prevalence rate in Somalia. This was perhaps due to an active campaign for the abandonment of FGM in the settlements and neighboring region. However the researchers found that 91% of women still intended to perform FGM on their daughters, compared to 75% of men. FGM was widespread among the Somali refugee community in Eastern Ethiopia and there was considerable support for the continuation of the practice particularly among women, although support for FGM Type III was declining.

It would appear that the influence of excisors within refugee communities is influential as demonstrated by Mitike & Deressa’s (Citation2009) research. The excisors included in the study were aged between 30 and 70 years and most were illiterate (73%). Of the participating 26 excisors, 77% reported that they relied on the income derived from performing FGM to support themselves and their families. The majority did not have other sources of income other than the food rations supplied by UNHCR. But interestingly, 96% of the excisors stated that they preferred to perform milder forms of FGM (i.e. not FGM Type III). The researchers revealed that a shift from FGM Type III to milder forms of FGM had taken place. This might be attributable to anti-FGM campaigns that were active in the region at the time of the study. The role of excisors in changing attitudes and behavior concerning FGM in refugee contexts requires further investigation as they could be highly influential in tackling FGM in these situations.

The fear of SGBV in humanitarian contexts can mean that parents opt to have FGM Type III performed on their daughters on the assumption that it will prevent them becoming victims of SGBV, in particular rape. However, FGM is not necessarily a protection against SGBV. For instance, in refugee camps in Sudan, researchers asserted that young girls aged as young as ten were found to be pregnant as a result of rape and experienced several serious complications, some of which were fatal, due to their FGM status (Ryan et al., Citation2014). DFID (Citation2013) suggest that providing safe environments for girls and women should be a priority in refugee settlements, to reduce the incidents of SGBV.

Research suggests that the practice of FGM amongst FGM practicing refugees might be being sustained by knowledge that FGM is illegal in the countries where refugees hope to resettle, such as in Australasia, Europe and North America. For instance Mohamed and Teshome (Citation2015) found that some Somali refugees living in Finland had performed FGM on their daughters in refugee settlements before leaving for Europe, as they were aware that FGM was illegal in Finland. Researchers found a similar trend among Somali refugees living in Norway who had continued the practice of FGM whilst in refugee settlements with the help of local excisors before being granted asylum in Norway (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012). After settling in Norway many Somali refugees stated that they regretted subjecting their daughters to the practice before resettlement and wished to discontinue the practice as its social value had diminished in Norway. For example, interviews undertaken by the researchers with younger generations of Somali refugees living in Oslo, Norway indicated low stigma experienced by uncut girls, from both female peers and young males, who are potential husbands. This was probably due to the fact that most of the Somali girls in the social network were uncut, and hence the reference groups are changing social norms to align with the new cultural environment they now are part of (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012). What these examples illustrate is the importance of educating refugees and asylum seekers from high FGM prevalence regions or countries of, not only the legal situation in countries of asylum (IOM, Citation2009), such as Finland and Norway, but also that refugees already resident in these countries have changed their attitudes and behaviour toward the practice and that being uncut is acceptable amongst diaspora communities in these countries.

Migration of non-FGM practicing groups to regions/countries with high FGM prevalence

The impact of migration on people who do not practice FGM, to regions or countries where FGM is practiced, has received very limited attention in the literature. However the trend appears to be that FGM non-practicing migrants moving to high prevalence regions have taken up FGM in order to integrate into their new social environment. For instance in Sudan, there are ethnic and religious variations of FGM practices across the country. FGM was traditionally practiced in the northern parts of the country but has spread to other non-FGM practicing ethnic groups, in other parts of the country, as displaced people from the west and south of the country moved to safety in the northern regions (before the separation of South Sudan from Sudan in 2010) (IOM, Citation2009). This “cultural influence”, and acculturation, has led to the adoption of FGM by ethnic groups in the western, and southern parts of Sudan as well as South Sudan. Traditionally non-practicing migrants now practice FGM on their girls, so they can become well integrated in their new host communities (LANDINFO, Citation2008). A similar trend has occurred in Mali where FGM was virtually non-existent in the sparsely inhabited north of the country (home to the Songhai and Tamasheq ethnic groups that do not traditionally practice FGM) (Andro & Lesclingand, Citation2016). However internal displacement from the northern regions of Mali where prevalence of FGM is low, to southern parts of the country (where FGM is common) resulted in migrants feeling ostracized for not being circumcised. Families from the north felt pressured to perform FGM on their daughters to enhance their social inclusion into the new host communities (IOM, Citation2009; DFID, Citation2013).

Very little research has been undertaken on the role of returning migrants to challenging the social norm that supports the practice of FGM. However research undertaken on the impact of return international migrants to Mali has come up with some interesting findings (Diabate & Mesple-Somps, Citation2014) which suggests that returning migrants do have a role to play in ending FGM in their home communities.

Although not in the Arab League Region, Mali does provide an interesting case study. Mali is a country with high FGM prevalence of 89% that is proving hard to reduce, it is also a country which historically produces high levels of international migration to other African countries as well as Europe. Migrants from Mali regularly migrate to countries where FGM is uncommon or prohibited, such as Ivory Coast and France. Diabate & Mesple-Somps (Citation2014) used an original household level database coupled with census data to calculate the extent to which girls under the age of 15 years, living in villages with high rates of migrant return were at risk of FGM. They found that girls living in villages with returned migrants were less likely to be subjected to FGM than girls living in villages with no or few returning migrants. This result was surprisingly driven by migrants returning from Ivory Coast, rather than from Europe. This indicates that the attitudes of migrants who had lived in an African country where FGM is not customary, has more impact on FGM risk in country of origin than returned migrants from non-African countries where FGM is uncommon. Mesple-Somps (Citation2016) explains

Malian migrants in Cote d’Ivoire are able to observe that there are customs in an African society that do not pressurize women to be cut and that uncircumcised girls do not suffer from social exclusion problems… (Mesple-Somps, Citation2016, p. 8).

Mesple-Somps suggests that returning migrants can be a force for change in ending FGM in their home countries as they have enhanced economic and social status on their return. In addition, as returnees they tend to be older and therefore hold a higher rank in the Malian social hierarchy, which makes social norm transformation more effective (Mesple-Somps, Citation2016). The evidence from this research suggests that return migration can be a vehicle for the transfer of new social norms, labeled “social remittances”. It also demonstrated that return migration flows are more efficient in social norm transformation than diaspora communications from current migrants (Mesple-Somps, Citation2016).

Migration of FGM practicing groups to regions/countries with low FGM prevalence

Migrants from FGM practicing countries or regions have to reconcile two contradictory pressures following settlement in a non-FGM practicing country, namely that in countries of destination FGM is prohibited and regarded as a violation of human rights, whereas in regions or countries of origin the practice of FGM is widespread and a social norm (Andro & Lesclingand, Citation2016). This can create confusion at best, and identity crisis and psychological problems at worse (Vloeberghs et al., Citation2011, Citation2012). Yet the impact of acculturation and the Western cultural context on migrants’ attitudes toward the practice of FGM has received little attention by researchers. The few studies that have been undertaken have tended to be undertaken in Western Europe (Germany, Netherlands, Norway, Sweden and UK) and amongst migrants from FGM practicing countries in the Horn of Africa, in particular, Somalia, Eritrea and Ethiopia.

Lien and Schultz (Citation2013) describe and analyze the way in which persons socialized in a cultural context where FGM is highly valued, received and processed information that contradicts and devalues the meaningful traditions and norms they internalized as children. They undertook multi-method anthropological research with 26 anti-FGM activists living in Norway that originated from The Gambia and Somalia, to find out what had triggered such strong commitment to abandon FGM. They used Spiro’s Internalization Theory to analyze their information. Spiro (1997, cited by Lien & Schultz, Citation2013) views individuals as active participants in cultural paradigmatic change, from a social norm where FGM is accepted and expected, to one where FGM is unacceptable and abandoned. Lien and Schultz (Citation2013) explored what was needed to get migrants to these levels so they would denounce FGM. They concluded that attitudinal change would not automatically happen merely as a consequence of resettling in a low FGM environment. They propose that targeted relevant information is required. However they concluded that if the information is to have impact, it must be delivered by a credible and trustworthy “cultural insider.”

Many western countries have laws and procedures in place that outlaw FGM. These were developed in response to migration from countries where FGM exists. France was the first country to criminalize FGM (1979) with Sweden (1982) and the UK (1985) following. The USA, Canada, Australia and Norway passed legislation in the 1990s and other European countries in the twenty-first century (Andro & Lesclingand, Citation2016). Some countries have specific laws prohibiting FGM (e.g. UK) whilst others have included the criminalization of FGM in their legislation on child abuse and mutilation (e.g. France) (EIGE, Citation2013; Johnsdotter & Mestre i Mestre, Citation2015, Citation2017). Almost all laws include an extra territoriality clause, enabling the protection of girls from FGM who may be taken abroad for the procedure, such as to their parents’ country of origin. The IOM (Citation2009) argues that combating FGM in Western countries is particularly challenging, as awareness-raising activities can easily be perceived by migrant groups as judgmental or morally offensive. This could result in negative reactions in migrant communities toward the law.

Despite the legislation passed by all EU countries criminalizing FGM, less than 50 court cases concerning FGM have been brought, with the majority of these taking place in France in the 1980s and 1990s (Johnsdotter & Mestre I Mestre, Citation2017). These were analyzed in a 2015 EU Report (Johnsdotter & Mestre I Mestre, Citation2015, Citation2017). The Report’s authors suggest this number is “surprisingly small” considering the hundreds of thousands of migrants from FGM practicing regions and countries living in Europe (page 42).The authors conclude from this that:

It is reasonable to believe that an important explanation for the scarcity of confirmed cases reflects substantial cultural change after migration in many immigrant communities… (page 42).

In an article published by Johnsdotter & Essen (Citation2016) a year after the report, pose the following questions:

The key question is whether illegal female circumcision takes place on a large scale, but goes unnoticed and thus unreported to authorities: Are there bountiful unrecorded cases among migrants who uphold their traditions in secretive manners?….Another possibility is that the scarcity of confirmed cases reflects substantial cultural change after migration. (Johnsdotter & Essen, Citation2016, p. 18).

Despite a number of studies being published on the impact of migration to the West and Europe in particular, the answers to these questions are not clear.

The earliest study on the impact of migration to the West by people from a high FGM prevalence country was published in 2004 (Morison et al., Citation2004). This presented the results of the experiences and attitudes concerning FGM of young Somalis living in London, UK. This study found that 82% of women and 52% of men were in favour of the discontinuation of FGM following migration to the UK. Unsurprisingly the results showed that members of the older generation, new arrivals and those not well integrated into the host society were more likely to uphold traditional norms and values, with women less likely than men to agree with the assumptions about sexuality and religious beliefs that underpinned the practice amongst the Somali community.

Research undertaken in Sweden, Germany and Netherlands confirm the trend amongst migrants to reject FGM. In a study of 33 Ethiopian and Eritrean migrants, including Christians and Muslims, living in Sweden, Johnsdotter et al. (Citation2009) found a “firm rejection of all forms of FGC” with no clear indication of the reason for this (Johnsdotter et al., Citation2009, p. 114). A mixed method study in Hamburg, Germany, which included 1767 participants from 26 FGM practicing countries, including Ghana,

Ethiopia and Cameroon, as well as 91 key informants, revealed widespread opposition to performing FGM on girls. Of the migrants interviewed 80% supported the discontinuation of FGM. The remaining 20% either supported the continuation of the practice, or reported uncertainty (Behrendt, Citation2011). Men were more likely than women to be in favour of FGM or to be unsure about the future status of the practice. In the Netherlands it is reported that migration to the Netherlands had led to a shift in how women perceive FGM, making them more aware of the negative consequences of FGM. Migration was described by women as a form of liberation, particularly from the social pressure to comply with a harmful tradition (Vloeberghs et al., Citation2012, p. 689) particularly since after migration they were living in nuclear families rather than in extended families as in their home country (Vloeberghs et al., Citation2011). Few participants had subjected their daughters to FGM with most demonstrating “active resistance against this ritual” (Vloeberghs et al., Citation2011, p. 101). The researchers explained this as being “The realization that FGM is not a religious requirement has influenced their change in attitude, as had the ban on FGM in the Netherlands” (Vloeberghs et al., Citation2011, p. 101).

Research undertaken in Switzerland (Vogt et al., Citation2017) compared the attitudes concerning FGM amongst Sudanese migrants living in Switzerland (84 participants) with Sudanese living in the home country (a randomly selected sample of 2260 adults living in the State of Gezira, Sudan). The analysis showed that Sudanese migrants living in Switzerland had significantly more positive attitudes toward uncut girls than Sudanese people living in Sudan. In fact Sudanese migrants were relatively positive about uncut girls. The researchers suggest that the Sudanese that migrated to Switzerland may constitute a special sub-set of the population of origin, being in general better educated than their compatriots back in Sudan. In addition those who migrate might already have changed their attitude to FGM and the move to Switzerland enabled them to change their behaviour concerning FGM in line with their changed attitudes.

In a review of current knowledge on cultural change concerning FGM after migration to the West, Johnsdotter and Essen (Citation2016) conclude there are “trends of radical change in this practice, especially the most extensive form of its kind [FGM Type III].” (page 21). They suggest the questioning of the Muslim belief that Islam requires FGM, especially when Muslim migrants interact with other Muslims that do not circumcise their daughters, is an important factor. It is argued that migrants reassess the religious imperative for FGM whilst in exile and then reevaluate and re-interpret FGM as a violation of fundamental Islamic teachings (Johnsdotter, Citation2003, p. 361). Recent research in Norway investigating Somali migrants’ attitudes to FGM confirm and offer more information. In one of the few quantitative studies, which used respondent-driven sampling, Gele, Johansen, et al. (Citation2012) examined whether or not Somali migrants’ exposure to Norwegian culture had altered their attitudes and behaviours toward the tradition of FGM. The sample consisted of 212 participants equally divided between women and men. The results indicated that 70% of the sample supported the discontinuation of all forms of FGM, with 81% declaring they had no intention to submit their daughters to FGM. In a parallel qualitative study of 38 Somali women (55%) and men (45%) migrants living in Oslo in 2011 (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012) provides some explanation for this trend. Thirty-six of the participants rejected all types of FGM for a variety of reasons. As Gele, Kumar, et al. (Citation2012, p. 14) explain

The result [of the study] shows that FC [female circumcision], which was formerly considered a form of cleanliness and an essential religious requirement, is now considered by Somali immigrants in Oslo as harmful, barbaric, and un-Islamic.

In other words the research reveals that the social norm supporting the continuation of FGM amongst the Somali diaspora community living in Oslo is weakening and arguably a tipping point has been reached. As the authors state: “being uncut was seen by both female and male participants as giving a person a higher status” (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012, p. 14). However they did conclude that “there could be a minority group within the community who are sympathetic to the girls’ circumcision but who cannot perform it because they are afraid of being prosecuted” (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012, p. 12). The research indicated that many of the participants feared the pressures from grandparents back home, leading Gele et al to warn

Thus the pressures posed by grandparents regarding the circumcision of girls can be a real threat to the elimination of the practice among Somalis in exile. As a result, awareness campaigns and efforts against FC [female circumcision] should be extended to FC-practicing countries which serve as a source of pressure on immigrants in the West. (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012, p. 15)

The pressure from relatives in the home country was also identified as an issue in perpetuating FGM in a qualitative study undertaken by Isman et al. (Citation2013) with eight Somali female migrants in Sweden. The participants recognized the negative health effects of FGM, but still acknowledged the positive cultural values of the practice. The main positive reason for performing FGM was stated as ensuring virginity in order to protect the honour of the family, as well as avoiding shame and ensuring purity and cleanliness. Some also mentioned FGM as a symbol of their country of origin, an identity marker. All participants stated that they had knowledge about families who had subjected their daughters to FGM after settling in Sweden. In another study on FGM among immigrants from North Africa, who were residing in Scandinavia (Berg & Denison, Citation2013), 73 out of 220 women interviewed, reported being genitally cut during a return visit to their home country and 15 of them explained that they had their daughter cut while living in Scandinavia. Similar data confirming the performance of FGM in Western countries has been reported by others, indicating the need to strengthen protection systems in these countries.

Research undertaken by Wahlberg et al. (Citation2017) gives more detailed information and present the primary outcomes from baseline data on attitudes toward FGM by Somali migrants living in Sweden. The purposive sample consisted of 372 Somali Muslim women and men, of which 206 had lived in Sweden for less than 4 years. Ninety-eight percent of the women in the sample had been subjected to FGM, 83% having experienced Type III. The research took place in Gothenburg and Malmo in Sweden in 2015. Whilst 83% of all participants said they did not think any form of FGM was acceptable, the remaining 17% stated that pricking (FGM Type IV) was okay. Amongst established Somali migrants, 75% reported they wanted their daughters to remain intact, but 23% wanted their daughter to be pricked. Amongst newly arrived participants, 53% did not want their daughters to be subjected to FGM, but 39% reported that they would perform pricking (FGM Type IV) on their daughters. The research demonstrated that the proportion of migrants opposing FGM increased over time of living in Sweden. The approval of FGM amongst migrants who had lived in Sweden for less than two years was found to be 11 times higher than Somali migrants who had lived in Sweden for 15 years or longer. The researchers concluded that with migration the social context changes and the pressures to perform FGM and other traditional practices maybe reduced, allowing families to renegotiate the practice of FGM (Wahlberg et al., Citation2017). However, the majority of those who upheld the practice of FGM supported pricking (FGM Type IV) a practice that has become popular amongst the Somali diaspora. There is debate in Sweden as to the legal status of pricking, as some argue it does not cause any anatomical changes to the female genitalia so should be allowed, whilst others regard pricking as a violation of female human rights and bodily integrity and argue it should be outlawed (Wahlberg et al., Citation2017, p. 9).

There is very limited research on understanding the attitudes and practices concerning FGM of refugees from high FGM prevalence countries after migration to the USA. What research that has been done tends to focus on migrants from Somalia. Due to political insecurity in Somalia, it is estimated that a quarter of the country’s population have migrated (Gele, Kumar, et al., Citation2012). Since 1983 over 50,000 Somali refugees have resettled in the USA (McNeely & Christie-de Jong, Citation2016). Somalia has the highest FGM prevalence in the world at 98% with FGM Type III being the most common type. In the USA FGM is illegal. This raises interesting issues of acculturation of migrants to the host country and the impact on migrant population’s beliefs, attitudes and practices concerning FGM. In 2013 McNeely and Christie-de Jong (Citation2016) undertook a qualitative study with 12 female refugees from Somalia living in Denver, USA to determine if attitudes and practices concerning FGM had changed since migration by these women (McNeely & Christie-de Jong, Citation2016). All had been subjected to FGM before settling in the USA, with 11 reporting having had FGM Type III and one having FGM Type I (which she called sunna) (McNeely & Christie-de Jong, Citation2016). All participants were Muslim and had lived in USA for between 4 months and 12 years. All were aware that FGM was illegal in the USA.

What was interesting about this sample was that all of the women had spent time as refugees in Africa before being resettled in the USA. Ten of the women had spent extended periods of time as refugees in Ethiopia with one in Kenya and one in Egypt. Those who had been refugees in Ethiopia reported that there had been very active NGO led campaigns in the area, in particular addressing the complications associated with infibulation (Type III), explaining the benefits of sexual intercourse without infibulation, with the overall message being the abandonment of FGM. These participants reported that these anti-FGM interventions in Ethiopia changed their view of FGM and signified the moment they began to question the continuation of FGM and decided to stop performing FGM Type III. These campaigns also coincided with religious leaders in Ethiopia condemning infibulation and supporting sunna FGM. The awareness raising in refugee settlements in Ethiopia was reinforced when women settled in the USA, where they realized that “not all women in the world have FGM/C and described American women as “free” or “healthy”” (McNeely & Christie-de Jong, Citation2016, p. 162). Whilst most of the participants had rejected infibulation, they admitted that many Somali migrants may want to continue the practice, in particular opting for sunna (Type I) rather than the traditional infibulation (Type III). As McNeely & Christie-de Jong (Citation2016, p. 164) summarize:

Participants seemed relieved to abandon infibulation. However, all female participants believed Sunna (type I) to be the preferred practice. Although Sunna is illegal in the USA, all women spoke highly of its practice if they were not living in the USA.

It is unclear what the impact of migration from high FGM prevalence settings to low FGM prevalence countries has on attitudes toward FGM by migrant communities, particularly when migrants have passed through one or more countries. McNeely & Christie-de Jong’s research suggests that migrant experiences in Ethiopia have been instrumental in changing their attitudes to FGM which resulted in behaviour change once they settled in the USA where FGM is illegal. It would therefore appear that the interventions to end FGM in refugee settlements can bear fruit in refugee final country destinations, such as the USA.

Few research articles have been published on the impact of migration of people from high FGM prevalence countries to low FGM prevalence countries in Africa. What research has been undertaken is mainly focused on Somali refugees. However the impact on FGM does appear to be similar to that which happens when FGM affected families migrate to low prevalence Western countries, but there are also differences.

Jinnah and Lowe (Citation2015) report on their research on the beliefs and practices of FGM amongst Somali migrants in Kenya and South Africa. They argue that the context of migration provides women with opportunities to renegotiate and reinvent what FGM means to them. In 1991 Somalis began arriving in South Africa following political upheaval in their home country. Their overland journeys were long and difficult and involved several months of traveling across numerous countries. It is estimated that 25–45,000 Somali refugees now live in South Africa with half of them living in Johannesburg, particularly in the suburb of Mayfair. Here the streets are an extension of everyday life and this greatly shapes the (re)production of social norms, including FGM. Jinnah conducted qualitative research in this neighbourhood, including community mapping, to identify key nodes of social, economic and political power, resources, opportunities and threats (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015).

Nairobi in Kenya is home to many refugees, most originating from Somalia but also including migrants from Ethiopia, Eritrea and Djibouti. Many of these migrants had traveled from the large refugee settlements located in North and East Kenya, which are estimated to be home to over half a million refugees (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015). The lack of livelihood opportunities and difficult living conditions in the camps have led many to leave and migrate to urban centres, such as Nairobi, many settling in the suburb of Eastleigh. The population of Eastleigh is estimated at between 40-100,000 people and is highly transitory, with a constant flow of new migrants from Somalia. The space in this suburb has been appropriated for both public and private life with many people living with people from the same community and clan as in Somalia, thus replicating a sense of normality and continuity of social norms (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015).

Both groups of research participants whilst expressing irritation at “being lectured by advocacy officers working for NGOs on their intimate body parts” (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015, p. 380) had begun to question the practice of FGM following migration. The participants in Johannesburg indicated that this questioning of FGM was initiated by the “humiliation they felt when a medical professional in South Africa first noticed that they were circumcised”(Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015, p. 380). However, it would appear that FGM Type III was more common in Eastleigh, Nairobi than in Mayfair, Johannesburg amongst Somali migrants. There was agreement however, that FGM Types I, II and IV were becoming more common in both communities. Jinnah and Lowe (Citation2015) argue that living in close knit communities where private and public space is blurred, such as in Eastleigh and Mayfair, results in pressure to adhere to social norms. Also that living in intergenerational households increased the social pressure to perform FGM.

Jinnah and Lowe (Citation2015) found that in Johannesburg, Somali women expressed a feeling of being “free” from social pressure to perform FGM on their daughters. It is to be noted that intergenerational households were fewer there than in Nairobi, where parents expressed concerns that if their girls were not circumcised “they may become overly sexualized or the victims of preying young men, particularly non-Somali and non-Muslim men” (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015, p. 384). The researchers suggest that the re-thinking about FGM in Johannesburg and Nairobi was not straightforward as they conclude:

The parents we interviewed expressed concern at doing what was most beneficial for their daughters, and this lies at the crux of decisions made concerning circumcision. There was undoubtedly a move away from the extremity of pharaonic circumcision [FGM Type III], largely centered on changing understandings of health, gender, fertility, sexuality, and religious requirements, and so reshaping cultural practices in new settings. (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015, p. 384).

Discussion

Changes in the type of FGM performed following migration

Whilst the topic of the relationship between FGM and migration in the Arab League Region is under researched, all the research reviewed indicated that migrants from FGM practicing communities, in line with global trends, are generally choosing not to perform FGM Type III on their daughters. This appears to be mainly due to the effective communication of the health risks associated with this physically invasive form of FGM. When FGM Type III is performed research suggests it tends to be in situations where girls and women are vulnerable to SGBV, such as in refugee settlements (DFID, Citation2013); where integration with the host society is weak; and the social norm to continue with Type III is strong; again widespread in refugee settlements (Mitike & Deressa, Citation2009).

Some researchers claim that after migration, especially to Scandinavia and Switzerland, migrants abandon the practice of FGM. However, the evidence is not conclusive and other researchers suggest that many migrants do stop performing FGM Type III but continue to perform FGM Types I, II and IV. It would appear that there is an increasing trend for migrants living in the West to perform Type IV on babies or young girls in the belief that this will be undetectable by medical and legal authorities in countries where FGM is illegal. Or that FGM Type IV is not covered by the law (as is evidenced in Europe where the legal profession are debating whether FGM Type IV is mutilation and if it is covered by the law).

The migrant journey

Most of the research reviewed focused in migrants’ attitudes and practices concerning FGM in their destination country and often compared this with practices in their region or country of origin. However, what is clear is that many migrants have complex journeys which take them through many different countries with varying social norms concerning FGM. Many refugees now living in the West, for example, have spent large periods of time (over 10 years in some cases) surviving as internally displaced people, refugees living in refugee camps, leaving the camps and moving to urban centers to find work and then being resettled in the West. Little research has been undertaken on this “migrant journey” and how this affects attitudes and practices concerning FGM. Yet it is obvious that migrant attitudes and practices concerning FGM will be affected by the social norms and anti-FGM interventions that they experience on their journey. In some cases migrants have changed their attitudes toward FGM as a result of campaigns to abandon FGM conducted in refugee settlements, others have had negative experiences of healthcare services in refugee camps and choose to consult excisors and traditional medical practitioners about their health needs and so are not exposed to anti FGM messages.

We also know very little about how the migrant journey affects migrants who do not traditionally practice FGM. There is some concern that these migrants might adopt FGM in order to integrate in to host communities that do practice FGM in order to safeguard their social and economic security and to ensure their daughters’ marriage prospects.

The refugee camp/settlement

There are few studies of FGM in refugee camps. In those that have been published researchers indicate that FGM Type III is less favoured, being replaced with Types I, II and IV. This change appears to be the result of effective campaigns in regions of origin, in the refugee camp and/or in the host region. Other reasons given by researchers include public declarations by religious leaders that FGM is not a religious requirement, that excisors are not willing to perform FGM Type III and medicalization is not available (Furuta & Mori, Citation2008). In other situations where migrants have not been exposed to anti FGM interventions and the social norm is strong, researchers report that FGM continues, often with public celebrations (Simojoki, Citation2014). It is a very mixed picture.

FGM in refugee camps is also associated with parents trying to prevent their daughters from being the victims of sexual violence, including rape. Ensuring the safety and security of women and girls in refugee settlements is paramount if FGM is to be tackled. In addition appropriate healthcare facilities need to be available to treat and care for those that have suffered SGBV (DFID, Citation2013).

Researchers also highlight the need for effective communication from diaspora living in resettlement countries. There are reports that families are subjecting their daughters to FGM in refugee camps prior to resettlement in countries where FGM is illegal, without understanding that their compatriots in those countries are abandoning the practice. Thus, just telling parents that FGM is illegal in the resettled country is not enough to protect their daughters. Researchers conclude that if the message comes from a trusted cultural insider, such as a member of the diaspora, could be a successful initiative.

We believe that much more needs to be done to tackle FGM in refugee situations. This needs to be based on in-depth understanding of the drivers of the practice in these insecure and often violent situations.

Integration into host society

The level of integration of migrants into host communities and its effect on the practice of FGM have received little attention from researchers. What is evident is that whilst migrants from FGM practicing communities from the Arab League Region face the same issues of integration as other migrants, they do have an additional challenge and that is the healthcare needs of survivors of FGM. Most of the research reviewed focused on FGM affected migrants and their experiences of healthcare services in refugee camps and in the West (Cappon et al., Citation2015; Johnson-Agbakwu et al., Citation2014; Upvall et al., Citation2009; Varol et al., Citation2017). In most instances it was reported that there appeared to be a lack of understanding of the needs of survivors of FGM by healthcare professionals who had often not received training in FGM and were not confident in treating FGM survivors, especially during pregnancy and delivery. This was compounded by communication problems and the cultural sensitivities of the patients.

Research suggests that migrants who integrate well into the host society are more likely to abandon FGM than those who do not (or vice versa with migrants who do not practice FGM resettling in societies where FGM is the norm). However in situations where migrants live in geographical proximity to each other (i.e. ghettos, migrant suburbs, housing estates), where the use of private and public space is blurred and in situations where households comprise a number of generations and extended family members, research suggests that integration is likely to be difficult and the social norm perpetuating FGM strong (Jinnah & Lowe, Citation2015).

FGM as an identity marker

A number of researchers suggest that one reason why FGM continues following migration is because it is a mark of identity. This is especially the case in situations of poor integration, discrimination and marginalization of migrants (Alhassan et al., Citation2016). There is little understanding of FGM as part of individual and community identity and what happens to that identity following migration, particularly to a context where FGM is unacceptable and illegal. The psychological aspects of loss of identity and seeking a new identity are little understood in the context of migration and may account for resistance to ending FGM in migrant communities.

The role of men

No research reviewed exclusively examined migrant men’s perspectives of FGM but most did incorporate men’s views into the research. What the research revealed was that migrant men were in some cases in favour of ending FGM, in others not so, valuing the traditional and the family honour aspects of the practice. One area that requires urgent attention is the role of male sexuality and virility in the continuation of FGM, in particular FGM Type III and re-infibulation (Johansen, Citation2017). There is much research on FGM and female sexuality and sexual functioning, but very little on the male equivalent (Alsibiana & Rouzi, Citation2010; Berg et al., Citation2010; Berg & Denison, Citation2012; Rouzi et al., Citation2017). Many women reported undergoing re-infibulation to satisfy their husbands sexually (Johansen, Citation2017). Male sexuality and virility is clearly a driver of FGM that requires more attention.

Conclusions

The authors have highlighted the highly complex and dynamic situation concerning attitudes and practices associated with FGM in regions and countries of the Arab League Region. This is a region where people are on the move, regionally, internally and internationally. The effect of migration on the practice of FGM in both regions and countries of origin as well as destination are under-researched. What little research has been undertaken has been conducted primarily with Somali and Sudanese migrants in African urban settlements and refugee camps, and in the countries of North America and Europe where they have settled as refugees. In particular studies need to be undertaken on all migrants within and from the Arab League Region, such as those from Egypt, Oman, Djibouti as well as in refugee settlements in Egypt, Jordan, Lebanon and Turkey, to ensure we understand the drivers of FGM in a variety of migration contexts.

By performing a rigorous literature review we provide an analysis of the linkages between culture, social norms and practices of FGM and its manifestation among groups of migrants originating from the Arab League Region and their interaction with host communities, who may or may not be practicing FGM. The authors devised and used a FGM- Migration Matrix to explore the complexity of the situation focusing on three scenarios: migration from high prevalence regions of origin to high prevalence regions or countries of destination; migration of non-FGM practicing groups to destination regions and countries with high FGM prevalence; and migration of FGM practicing groups to destination regions and countries with low FGM prevalence. By using case studies from the research literature the importance of the “migrant journey” through regions and countries with different FGM prevalence and social norms, as well as levels of migrant integration with host communities, becomes apparent as does the importance of FGM as an identity marker.

The authors call for more research to be undertaken on the FGM-Matrix scenarios and the migrant journey through these different scenarios and the effect this has on migrant and host attitudes and practices concerning FGM. Developing an internationally agreed suite of quantitative and qualitative methodologies and methods to research the impact of migration on FGM would allow for more reliable regional and international comparisons to be made, good practice identified and the development and implementation of effective policies and interventions to end FGM and ensure the Sustainable Development Target to end FGM is achieved.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

References

- 28toomany. (n.d). FGM: The Middle East: 5 focus countries. https://www.28toomany.org/continent/middle-east/. 28toomany, London.

- Alhassan, Y. N., Barrett, H., Brown, K., & Kwah, K. (2016). Belief systems enforcing female genital mutilation in Europe. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 9(1), 29–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-05-2015-0015

- Alsibiana, S. A., & Rouzi, A. A. (2010). Sexual function in women with female genital mutilation. Fertility & Sterility 93(3), 722–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.10.035

- Andro, A., & Lesclingand, M. (2016). Female genital mutilation. Overview and current knowledge. Population, 71(2017), 217–296. https://www.cairn.info/article-E_POPU_1602_0224-female-genital-mutilation-overview-and.htm

- Barrett, H., Brown, K., A. Y., & Beecham, D. (2015). The REPLACE approach: Supporting communities to end FGM in the EU. A toolkit. Coventry University.

- Behrendt, A. (2011). Listening to African voices: FGM/C among immigrants in Hamburg: Knowledge, attitudes and practice. Plan International.

- Berg, R. C., Denison, E., & Fretheim, A. (2010). Psychological, social and sexual consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): A systematic review of quantitative studies. Report from Kunnskapssenteret nr 13. Norwegian Knowledge Centre for the Health Services.

- Berg, R. C., & Denison, E. (2012). Does female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) affect women’s sexual functioning? A systematic review of the sexual consequences of FGM/C. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 9(1), 41–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13178-011-0048-z

- Berg, R. C., & Denison, E. (2013). A tradition in transition: Factors perpetuating and hindering the continuance of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) summarized in a systematic review. Health Care for Women International, 34(10), 837–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2012.721417

- Burki, T. (2010). Reports focus on female genital mutilation in Iraqi Kurdistan. The Lancet, 375(9717), 794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60330-3

- Cappon, S., L'Ecluse, C., Clays, E., Tency, I., & Leye, E. E. (2015). Female genital mutilation: knowledge, attitude and practices of Flemish midwives. Midwifery, 31(3), e29–e35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2014.11.012

- DFID. (2013). Violence against women and girls in humanitarian emergencies CHASE Briefing Paper. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/271932/VAWG-humanitarian-emergencies.pdf

- DFID. (2014). Assessing the strength of evidence. DFID.

- Diabate, I., & Mesple-Somps, S. (2014). Female Genital Mutilation and migration in Mali. Do migrants transfer social norms? Dauphine Universite Paris, Document de Travail: UMR DIAL DT/2014-16. www.dial.prd fr.

- EIGE. (2013). Female genital mutilation in the European Union and Croatia. EIGE.

- Furuta, M., & Mori, R. (2008). Factors affecting women's health-related behaviors and safe motherhood: A qualitative study from a refugee camp in eastern Sudan. Health Care for Women International, 29(8), 884–905. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330802269600

- Gele, A. A., Kumar, B., Hjelde, K. H., & Sundby, J. (2012). Attitudes toward female circumcision among Somali immigrants in Oslo: A qualitative study. International Journal of Women’s Health, 4, 7–17.

- Gele, A. A., Johansen, E. B., & Sundby, J. (2012). When female circumcision comes to the West: Attitudes toward the practice among Somali immigrants in Oslo. BMC Public Health, 12, 697. http://biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/12/697

- Geraci, D., Mulders, J. (2016). Female genital mutilation in Syria? An inquiry into the existence of FGM in Syria. http://www.pharos.nl/documents/doc/female%20genital%20mutilation%20in%20syria%20-%20an%20inquiry%20into%20the%20existence%20of%20fgm%20in%20syria.pdf

- Hagen-Zanker, J., & Mallett, R. (2013). How to do a rigorous, evidence-focused literature review in international development: A guidance note. ODI Working Paper, London, UK. September. Odiorg.

- IDMC. (2017a). Global report on internal displacement, 2017. IDMC.

- IDMC. (2017b). Mini global report on internal displacement, 2017. IDMC.

- IRB. (2016). Djibouti: The practice of female genital mutilation (FGM), including the legislation prohibiting the practice, state intervention and the prevalence among the general population, the Midgan [Gaboye] and other ethnic groups or clans. https://www.ecoi.net/local_link/326371/452967_en.html

- IOM. (2009). Supporting the abandonment of female genital mutilation in the context of migration. http://www.iom.int/jahia/webdav/shared/shared/mainsite/projects/documents/fgm_infosheet.pdf

- IOM. (2016). Migration to, from and in the Middle East and North Africa: Data snapshot. https://www.iom.int/sites/default/files/country/mena/Migration-in-the-Middle-East-and-North-Africa_Data%20Sheet_August2016.pdf

- Isman, E., Ekeus, C., & Berggren, V. (2013). Perceptions and experiences of female genital mutilation after immigration to Sweden: An explorative study. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare: Official Journal of the Swedish Association of Midwives, 4(3), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.srhc.2013.04.004

- Jinnah, Z., & Lowe, L. (2015). Circumcising circumcision: Renegotiating beliefs and practices among Somali Women in Johannesburg and Nairobi. Medical Anthropology, 34(4), 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/01459740.2015.1045140

- Johansen, R. E. B. (2017). Virility, pleasure and female genital mutilation/cutting. A qualitative study of perceptions and experiences of medicalized defibulation among Somali and Sudanese migrants in Norway. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0287-4.

- Johnsdotter, S. (2003). Somali women in western exile: Reassessing female circumcision in the light of Islamic teachings. Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, 23(2), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360200032000139983

- Johnsdotter, S., & Essen, B. (2016). Cultural change after migration: Circumcision of girls in Western migrant communities. Best Practice & Research. Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 32, 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2015.10.012

- Johnsdotter, S., & Mestre I Mestre, R. M. (2015). Female genital mutilation in Europe: An analysis of court cases. European Commission – Directorate-General for Justice and Consumers. Publication Office of the European Union.

- Johnsdotter, S., & Mestre I Mestre, R. M. (2017). Female genital mutilation’ in Europe: Public discourse versus empirical evidence. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 51, 14–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2017.04.005

- Johnsdotter, S., Moussa, K., Carlbom, A., Aregai, R., & Essén, B. (2009). "Never my daughters": A qualitative study regarding attitude change toward female genital cutting among Ethiopian and Eritrean families in Sweden.” Health Care for Women International, 30(1-2), 114–133. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330802523741

- Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E., Helm, T., Killawi, A., & Padela, A. I. (2014). Perceptions of obstetrical interventions and female genital cutting: Insights of men in a Somali refugee community. Ethnicity & Health, 19(4), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2013.828829

- LANDINFO. (2008). Report on Female genital mutilation in Sudan and Somalia. http://www.landinfo.no/asset/764/1/764_1.pdf

- Lien, I. L., & Schultz, J. H. (2013). Internalizing knowledge and changing attitudes to female genital cutting/mutilation. Obstetrics & Gynecology International. 2013, 467028. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/467028

- McNeely, S., & Christie-de Jong, F. (2016). Somali refugees’ perspectives regarding FGM/C in the US. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 12(3), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-09-2015-0033

- Mesple-Somps, S. (2016). Migration and female genital mutilation: Can migrants help change the social norm? IZA World of Labor, 282. https://doi.org/10.15185/izawol.282

- Mitike, G., & Deressa, W. (2009). Prevalence and associated factors of female genital mutilation among Somali refugees in eastern Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health, 9(1), 264. http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/9/264

- Mohamed, S., & Teshome, S. (2015). Changing attitudes in Finland towards FGM. Forced Migration Review, 49, 87.

- Morison, L. A., Dirir, A., Elmi, S., Warsame, J., & Dirir, S. (2004). How experiences and attitudes relating to female circumcision vary according to age on arrival in Britain: A study among young Somalis in London. Ethnicity & Health, 9(1), 75–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/1355785042000202763

- Rouzi, A. A., Berg, R. C., Sahly, N., Alkafy, S., Alzaban, F., & Abduljabbar, H. (2017). Effects of female genital mutilation/cutting on the sexual function os Sudanese women: A cross-sectional study. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Gynecology, 217(1), 62.e1-6–62.e6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2017.02.044.

- Ryan, M., Glennie, A., Robertson, L., and Wilson, A. (2014). The impact of emergency situations on female genital mutilation. http://28toomany.org/media/uploads/the_impact_of_emergency_situations_on_fgm.pdf

- Shell-Duncan, B., Naik, R., & Feldman-Jacobs, C. (2016). A state-of-art-synthesis of female genital mutilation/cutting: What do we know now? October 2016. Evidence to End FGM/C: research to help women thrive. Population Council. http://www.popcouncil.org/EvidencetoEndFGM-C

- Simojoki, M. V. (2014). Female genital mutilation: Practices amongst the refugee population in Upper Nile State, South Sudan. Danish Refugee Council. https://drc.ngo/media/1191290/report-on-female-genital-cutting-in-upper-nile-state-april-2014.pdf

- UNHCR. (2015). Figures at a glance. http://www.unhcr.org/figures-at-a-glance.html

- UNICEF. (2013). FGM/C: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change. UNICEF.

- UNICEF. (2016). Female genital mutilation/cutting: A global concern. UNICEF.

- United Nations. (2016). Sustainable Development Goal 5, Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls. Sustainable Development Knowledge Platform. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/sdg5

- Upvall, M. J., Mohammed, K., & Dodge, P. D. (2009). Perspectives of Somali Bantu refugee women living with circumcision in the United States: A focus group approach. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(3), 360–368. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.04.009

- Varol, N., Hall, J. J., Black, K., Turkmani, S., & Dawson, A. (2017). Evidence-based policy responses to strengthen health, community and legislative systems that care for women in Australia with female genital mutilation / cutting. Reproductive Health, 14(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12978-017-0324-3

- Vloeberghs, E., Knipscheer, J., van der Kwaak, A., Naleie, Z., & van den Muijsenbergh, M. (2011). Veiled Pain: A study in the Netherlands on the psycho-logical, social and relational consequences of female genital mutilation.

- Vloeberghs, E., van der Kwaak, A., Knipscheer, J., & van den Muijsenbergh, M. (2012). Coping and chronic psychosocial consequences of female genital mutilation in The Netherlands. Ethnicity & Health, 17(6), 677–695. https://doi.org/10.1080/13557858.2013.771148

- Vogt, S., Efferson, C., & Fehr, E. (2017). The risk of female genital cutting in Europe: Comparing immigrant attitudes toward uncut girls with attitudes in a practicing country. SSM - Population Health, 3, 283–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2017.02.002

- WADI. (2010). Female genital mutilation in Iraqi-Kurdistan: An empirical study by WADI. WADI, Frankfurt.

- Wahlberg, A., Johnsdotter, S., Selling, K. E., Källestål, C., & Essén, B. (2017). Baseline data from a planned RCT on attitudes to female genital cutting after migration: When are interventions justified?. BMJ Open, 7(8), e017506. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017506