Abstract

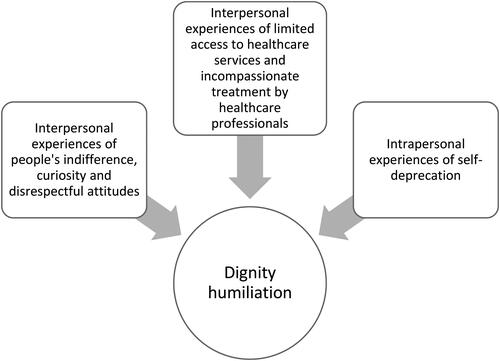

In this study, we explored key sources that led wives who care for their husbands with dementia at home to experience dignity humiliation – an issue that affects the well-being of women around the world. Through hermeneutic interpretation of in-depth interviews, three key sources of this were identified: interpersonal experiences of people’s indifference, curiosity and disrespectful attitudes; interpersonal experiences of limited access to healthcare services and incompassionate treatment by healthcare professionals, and; intrapersonal experiences of self-deprecation. Knowledge of key sources leading to dignity humiliation can be used to improve interdisciplinary healthcare practices and policy development, specifically relating to this group of caregivers.

Over the last decade, a great deal of attention has been paid to researching how experiences of dignity affect the well-being of people living with dementia (e.g. Sagbakken et al., Citation2017; Tranvåg et al., Citation2015, Citation2016; van Gennip et al., Citation2016). However, far less attention has been given to efforts to increase knowledge of the key sources that affect how their family caregivers experience dignity – an issue that concerns the well-being of women around the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO, Citation2021) women provide the majority of informal care for persons living with dementia – accounting for 70% of carer hours. Around 2/3 of family caregivers are women, and most of them spouses (Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2015; WHO and Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2012). By listening to and giving voice to the generally unexplored experiences of older women caring for a husband with dementia at home, this study sets out to remedy this research gap, namely through the exploration of key sources that lead to dignity humiliation in the everyday lives of these caregiving wives.

Background

Dementia is a syndrome caused by a variety of brain conditions that affect the person’s thinking, memory, behavior and ability to perform activities in their daily lives, and today more than 55 million people live with dementia worldwide. With nearly 10 million more people being affected by the disease every year, a number expected to rise to 78 million by 2030 and 139 million by 2050 (WHO, Citation2021). In developed countries, estimates show that around 2/3 of people with dementia live at home (Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2015). This means that, as their illness progresses from mild to moderate and then on to more advanced levels, they require an increased need for care and support. Family caregiving is the cornerstone of dementia care. Consequently, dementia also influences the lives of the family members who act as caregivers – in particular those who take on the primary role of providing everyday care (Alzheimer’s Society, Citation2014; World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2012).

Being a family caregiver for a person with dementia can negatively affect the caregiver’s physical and mental health, social relationships and well-being. Increased awareness of the disproportionate effect the strain of being a caregiver has on women is an important topic to address. Knowledge of how their emotional stress can be reduced, and how their coping, self-efficacy and physical health can be improved is critical when it comes to ensuring that they have the skills needed to continue in their caregiving role (WHO, Citation2017).

Caring for a home-dwelling spouse with dementia involves dealing with multiple tasks as the illness progresses, from the initial, supporting activities of daily living such as household upkeep, social activities and financial assistance, to the more personal support and care required – over time, this extends to providing continual supervision and assistance (World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2012). Comparing caregiving female and male spouses, as well as female and male adult children, female spouses are found to be the most vulnerable group – they experience more burdens and are more likely to experience depression, and lower levels of physical health than others (Friedemann & Buckwalter, Citation2014). Older female spouses living in the same household as the person in need of care have reported higher caregiver-related burdens than other family caregivers (Kim et al., Citation2012). During early phases of the illness, lack of knowledge about dementia and what causes their husband’s changing behavior may lead some to experience incomprehensibility and loss of control (Potgieter & Heyns, Citation2006). Potential factors that make female spouses in particular especially vulnerable to the caregiver burden and strain includes the type of emotional reaction pattern they may have to such situations, and the fact they spend more time on caregiving activities (Friedemann & Buckwalter, Citation2014). Caregiving wives may experience changes to their identity, in that their husbands influence the way they perceive their marriage and perception of the self, this includes feeling a marked change in the nature and closeness of the marital relationship (Boylstein & Hayes, Citation2012). However, love, commitment and the desire to return the care and support the person with dementia have provided for them over the years are found to make up the core foundation for the reasons behind the everyday caregiving choices made by women caring for a family member with dementia (Dunham & Cannon, Citation2008).

Older wives caring for a husband with dementia in the home also strive to uphold their experience of dignity as a positive source for both the spouse and themselves. As found by Tranvåg et al. (Citation2019) this sense of dignity reported among the wives relates to their being able to; preserve their own personal integrity, feel a sense of achievement and control in their everyday lives, and acknowledge the worthiness and uniqueness of each human being. Crucial sources that may help preserve their sense of dignity include their being able to; experience personal growth, maintain a certain level of continuity in their daily lives, be a good wife and caregiver, preserve their husband’s dignity, and experience that they are truly being understood by others (Tranvåg et al., Citation2019). However, little is known about what may undermine their experience of dignity – being key sources behind what result in their experiences of dignity humiliation. An improved understanding of this could further support interdisciplinary healthcare practices and policy development, specifically that which is relevant to the needs of numerous older wives caring for a home-dwelling husband with dementia.

Aim

In this present study, our aim was to explore and describe key sources that lead women caring for a home-dwelling husband with dementia to experience dignity humiliation.

Methodology

An exploratory design based on qualitative interviews was employed as this approach is advantageous when investigating the manifestation and underlying processes of a distinct phenomenon, of which we currently have a limited knowledge of (Polit & Beck, Citation2010). The study was founded on Gadamer’s philosophical hermeneutics (2004), which emphasizes the hermeneutic interpretive process as a fundamental factor in developing an understanding of the nature of a specific phenomenon and what that then means.

Pre-understanding

To increase the transparency (Hiles & Čermák, Citation2007) and trustworthiness (Guba et al., Citation1994; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Polit & Beck, Citation2010) of the study, and to help the reader identify the interpretive context of the research, the researchers’ pre-understanding of the study should be outlined (Gadamer, Citation2004). As the authors of this article our preconceptions of the study were that we would find that the older women caring for a home-dwelling husband with dementia would report experiencing dignity humiliation through the loss of control over their lives, when they are not allowed “to be themselves”, and when they feel as if they are being treated in a disrespectful manner by healthcare professionals (HCPs). We also assumed that dignity humiliation would be experienced when the husband’s dementia progressed and thus negatively affected their spousal relationship, for instance becoming the husband’s caregiver and experiencing a loss of the communion they previously had in their relationship. In addition to our own preconceptions, the previous research presented in the background paragraph above also formed part of our pre-understanding of the research.

Setting and participants

Six Norwegian women aged 61 to 81 were recruited from two Norwegian Hospital Memory Clinics using a strategic sampling approach based on certain criteria. They had to be: Aged 60 years or older; being women caring for a husband who had been diagnosed with mild to moderate dementia, living together in the same home as the husband; speaking of one of the Scandinavian languages or English, and; willing to be interviewed about their experiences and perceptions of dignity humiliation in their role as a caregiving wife. Participant recruitment was conducted by the medical doctors responsible for diagnostic examinations and follow-up treatments of the participants’ husbands, in cooperation with the clinical nurses.

Data collection

When the data collection took place, the time since the participants’ husbands had been diagnosed with dementia ranged from six months to three years. Individual in-depth interviews were utilized as a tool for the data collection process (Brinkmann, Citation2015). All interviews were carried out in the caregiving wives’ homes. A modifiable interview guide was used to structure the interviews, including the following main questions: In your everyday life after your husband developed dementia, have you, as his caregiving wife, experienced that your dignity had been humiliated in any way? Based on your experiences, what does dignity humiliation mean to you? Can you describe a situation in which your sense of dignity was humiliated in relational interactions with others? How would you describe the nature of dignity humiliation from your perspective as caregiver? Based on a method of active listening regarding what the caregiving wives’ reflected on and communicated, additional follow-up questions were posed. These were intended to explore their experience and perceptions in greater detail, adding depth to the data collection. One interview was conducted with each participant, and all interviews were recorded on a MP3 voice recorder to ensure verbatim transcriptions.

Interpretation and theoretical framework

The interpretive hermeneutic process (Gadamer, Citation2004) of developing a new understanding of how caregiving wives experience dignity humiliation began with the individual reading of the transcribed interview texts. Each member of the research team repeatedly read the texts, noting down keywords, phrases and reflections from each text. In this process, the preliminary interpretation of each new interview text made the interview texts we had already explored more understandable, while simultaneously adding a new meaning of their own. The emerging patterns of meaning were then examined while we also tracked data inconsistencies and contradictions in the texts, allowing us to question our preliminary interpretations. In this process, our pre-understanding did, of course, constitute some of our initial understandings of the results. We therefore endeavored to identify these preconceptions through individual reflection, as well as in reflexive dialogues within the research group. While discussing various parts of each text, and the texts as a whole, the awareness of our pre-understandings guided us toward critically identifying and further understanding the material as well. This hermeneutic circle approach (Gadamer, Citation2004), in which researchers must move back and forth analyzing parts of the text individually and then the text as a whole, helped us move beyond our pre-understandings and gain an enhanced understanding of sources of dignity humiliation as experienced and perceived by the participants. The final part of the process involved categorizing the results of the study into themes.

In the interpretive process, human dignity – a core concept described in Katie Eriksson’s theory of suffering and theory of caritative caring (Eriksson Citation2006, Citation2018; Lindström et al. Citation2018; Bergbom et al., Citation2021) was found to be a fruitful theoretical basis for the empirical–theoretical dialogue we have used to discuss the study results. The foundation for the caritative caring theory is built on love, mercy and compassion – fundamental factors when it comes to alleviating suffering and promoting and protecting both health and life (Bergbom et al., Citation2021; Eriksson, Citation2002, Citation2018; Lindström et al., Citation2018). According to Eriksson, dignity is one of the core concepts of caring ethics. Human dignity can be understood through both an objective and a subjective dimension. The objective dimension, called absolute dignity, is inherent to all people, granted through the virtue of being human and is thus an unchangeable quality of everyone in regard to the right to be acknowledged and confirmed as a unique individual. In other words, absolute dignity cannot be humiliated, nor be taken away from any human being. On the other hand, the subjective dimension, termed relative dignity, is related to how human beings experience their everyday lives. Influenced by culture and other sociocultural factors, relative dignity is therefore both modifiable and changeable – it affects the individual’s well-being and inner self-worth as well as their sense of worthiness in relation to other people. In other words, relative dignity can be preserved through experiences of self-worth, and the recognition and confirmation of others, but it can also be dismantled and taken away when one experiences the feeling of being humiliated through the words or actions of someone else. In this way, relative dignity is constituted by an inner and outer dimension – both of which affect one’s everyday experiences of dignity (Eriksson, Citation2006, Citation2018; Lindström et al., Citation2018).

Ethical considerations

The ethical standards for medical research involving human beings as outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2013) were followed. Sensitivity toward the preservation of the caregiving wives’ integrity and dignity was prioritized at every stage of the study; anchored in our ethical responsibility as researchers, the ethical principles that guided our research process were that of moral sensitivity in light of the participating women’s vulnerability, wanting to ensure their well-being, demonstrating fairness, and respecting their personal utility. Each participant received both verbal and written information regarding all aspects of the study before they gave their consent to participate. They also received a copy of the interview guide as we believed this could help strengthen their understanding of the study and their ability to make the decision to decline or accept the offer to participate. Their right to withdraw from the study without consequence was also made clear both verbally and in writing. Whether the interview should be conducted in the researcher’s office or in their own home was a decision made by the participants. As researchers, we assumed responsibility for ensuring anonymity and confidentiality of the caregiving wives’ identities and the information they shared, and ensured the communication of the study results in an appropriate language that preserved their dignity. The study received ethical approval from the South-East Regional Committee for Medical and Health Research Ethics, Norway.

Results

We identified three key sources that led to experiences of dignity humiliation among women who care for a home-dwelling husband with dementia ().

Interpersonal experiences of people’s indifference, curiosity and disrespectful attitudes

The first key source that leads caregiving wives to experience dignity humiliation can be traced back to interpersonal aspects, meaning the experiences they have when interacting with other people, such as through their attitudes and actions, most of which the wives communicated as of a generally more curious and inquisitive nature than of a caring nature. This encompasses the way people, even friends, behave and ask questions. The wife was then likely to experience feelings of irritation and hurt on behalf of the husband, but also for herself. While most people interact with them in a respectful way, some do not:

I have probably experienced a bit of both, in fact, some positive, but some negative as well. And I feel that, for myself, but especially on his behalf … I probably think I’m just as sensitive to it as he is. (Ella)

A concrete narrative shows how both curiosity and negative attitudes lead to feelings of humiliation, but additionally how they lead to an increased determination among the female spouses in wanting to define who they still consider to be a friend, and who isn’t. The wife in the interview below speaks of a person who she had thought was her friend but who, instead of providing help and support, actually speaks behind the wife’s back and spread negative rumors about them:

I live in a small place, and I had heard that she (“a friend”) had said lot of things about my husband (concerning his dementia) … us … to people around here. So, I went over to see her, because this had irritated me to no end; she never came over to find out how my husband was doing. And then I thought … but I know that this person is one who … so often make a big deal out of nothing. So, I had a proper chat with her one day. We are on speaking terms, definitely, but I think that was a thought-provoking conversation for her! Because I said straight out that “I heard you told so and so and so and so, and how can you have known that?” She had problems explaining that, yes. (Ella)

Instances in which the wives experience dignity humiliation arise when other people, through their attitudes and actions, treat and refer to the spouse with dementia in a degrading manner:

We are stigmatized as soon as someone is hit by dementia. But we have said that friends don’t mean much anymore because they don’t give us much. It’s about taking care of each other and family. That is what is most important now. We don’t need to be involved in all this other stuff we’ve done for the last 20 years, because this stigma you are faced with … is very degrading. (Sarah)

The defamatory rumors spread as a result of the stigma around a dementia diagnosis creates a specific kind of wound here, in that the wives experiences these painful, demeaning incidents in which they feel they must defend both their husbands and themselves. The wife below did not refer to one specific situation in which she experienced dignity humiliation, but she did explain that she experiences a general sense of this when all her efforts to support her husband in their everyday lives go unrecognized, specifically by him. She explains:

If you clearly show that you do not appreciate what I’m trying to do … if you are completely superficial and never notice that I have done something positive, then I can feel humiliated. It’s important to see things in others, to see what they are doing, to think that this … this was good! (Theresa)

The wife in this instance sometime feels that her contributions and efforts at home are overlooked or taken for granted by her husband, and particularly in her own vulnerability of having had to take on this position, this then has a negative impact on her sense of dignity.

Interpersonal experiences of limited access to healthcare services and incompassionate treatment by healthcare professionals

The second key source of dignity humiliation as experienced by the wives was again of an interpersonal nature, but this time, the humiliation was two-fold; on the system level, this relates to their experience of only being able to access limited support and care from the healthcare services, while on the relational level, this comes from receiving incompassionate treatment by HCPs. First, on the system level, some of the wives described how they had experienced dignity humiliation due to unequal access to healthcare. One of them expressed that she felt it was degrading that her husband is unable to receive municipal healthcare services adapted to his needs, such that he could live a meaningful everyday life:

But they have nothing to offer him … there is no point in him being an outpatient at the nursing home day care center without doing anything … I have heard of municipalities that have services, where health workers take maybe two or three patients to a farm where they can do work, do something together, go for a walk, play games, maybe do a bit of carpentry … that is, do something productive. But that does not exist in our village. (Ella)

The wives also describe their sense of being discriminated against by a healthcare system that doesn’t provide the same level of care and treatment services for citizens with dementia compared to the services that other patient groups receive. In turn, as family caregivers, they then experience that they aren’t given the same status and rights as the family caregivers of other patient groups. They therefore experience a humiliating gap when it comes to the equal access of quality healthcare services for home-dwelling persons living with dementia:

We are not going to start weighing diseases against each other … but, his network (the husband’s friend who has cancer), they are offered … marriage counselling … they get to travel … they get rehabilitation … they get training … it’s wonderful to see and hear about the kind of services they (cancer patients and relatives) get. And then we are back to our category (dementia sufferers and relatives) and we are not offered anything … we applied (for a rehabilitation stay) and were rejected first, and then there was also such a conversation with the municipality because they also have to consider all this … so as soon as they received an application “with dementia” they distanced themselves. It was quite clear. To rehabilitate a dementia patient … they do not want it … despite the fact that the doctor (at the Memory Clinic) had attached a certificate and written to them about the situation. (Sarah)

This also then relates to the wives’ experiences of being put in a situation in which seeking help to get the appropriate municipal healthcare services for their husband becomes a demanding “struggle” between her and those responsible for delivering the appropriate support.

Secondly, on the relational level, the wives find that they occasionally do interact with HCPs whom they feel have neither the sufficient knowledge of their current life-situation, nor any understanding of the wives’ everyday efforts to ensure their husbands’ well-being. In such cases, the dialogue with the HCPs often feels degrading, and gives them a sense of being overruled:

There can be superficiality in healthcare professionals as well … something that one has struggled to do as well as possible, and then it is just swept away. I think I have noticed someone who perhaps should not have worked in the healthcare system, who has no compassion … yes, because care is probably one of the most important things. (Theresa)

The wives report that they sometimes feel that the HCPs don’t take their needs into account, and that they fail to interact with them with respect and compassion:

But it’s speaking with healthcare professionals, and I think that if they know something about … about how to act when one is to safeguard another person’s dignity … how should one act when talking to the spouse? … They must have … they must … take into account his situation and my situation. (Elsie)

When the HCPs present them with solutions based on their professional expertise, the wives report that they feel as if they were being instructed as to “what is best for them”. Thus, they feel a kind of normative humiliation in regard to their personal integrity, in that it was as if the HCP is questioning their ability to make autonomous choices on behalf of themselves and for their husbands:

… without them saying: “you should do that”, because then they cross the line I think, and say what will be best for me, which they know nothing about … then I feel that they humiliate my … my ability to think, to make my own decisions. (Alice)

This indicates that when the wives experience such normative attitudes and behaviors from the HCPs themselves, it is as if they are crossing the wives’ personal boundaries and that they devalue their integrity and ability to make sound, autonomous decisions themselves.

Intrapersonal experiences of self-deprecation

The third key source we identified as a source of dignity humiliation is of an intrapersonal nature, concerning the wives’ experiences of self-deprecation regarding how their own personal feelings, needs and thoughts are often in conflict with their basic values. When feeling that they do compromise their own moral integrity, these experiences also relate to personal identity, as they undermine the essence of who they are and want to be. Such intrapersonal experiences also encompass their feelings of being burdensome, due to the growing realization that they need to ask for help and support from municipal healthcare services, just to ensure sufficient care for the husband. Accepting that necessary help from the municipal healthcare services sometimes results in a sense of giving up on their basic values and principles they hold about life, as it impacts their sense of control, independence, freedom and self-perception. As part of this, some experience this as if they then loose part of themselves, meaning that their very self and their relationship with the husband changes forever. For them, life takes a turn that force them to involuntarily become recipients of such help, influencing their role as a woman and spouse and their relationship as husband and wife:

… to do what I experience as right and proper… has to do with dignity… to be able to… then (if one starts using municipal healthcare services) I feel that I cannot do it (what is right and proper) so that I would say is humiliating in a way, that I should not cope with this… so… (Irene)

One of the other wives expresses herself like this:

What you have managed or done, or achieved in life, why should it be different now? Why is it that I cannot control my own life like … as I have done before, without talking to anyone else about it? But it is … I think it is a very good service, but I have not quite … I am not there … it takes … deprives me … asking things of others … and then it becomes such a collective matter … decision: “then we do this and that in that situation” and I don’t want that … (Alice)

In their current state of vulnerability, the female spouses also find it hard to deal with and are pained by the fact that they are no longer able to provide the care their husbands require. Asking someone for help or relief in certain situations is difficult for some of the wives, even if the suggestion to do so comes from HCPs. The transition from complete control and freedom in one’s own life to then having to talk to others about their situation is described as demanding for the wives; it feels like a step on the path toward being entirely dependent on others.

Another aspect that contributes to this sense of degradation occurs in cases in which both husband and wife are exposed to dignity humiliation simultaneously. An example of this can be seen in the situations in which people approaches the wife rather than directly addressing her husband, which then results in the wife having to respond on behalf of the husband:

Everyone turns to me, both because my husband is hard of hearing and because he spends a lot of time perceiving what has actually been said. And then I answer instead, and I feel in a way that I am offending him myself; I insult him in a way because I should have kept quiet and asked him to explain how it was. I should explain to him a lot more about what the question meant. And then I offend him, but I also offend myself a little bit by doing so. (Alice)

In interactions like this with people who do not know the couple, the wives often find it easier to be the one to respond. This leads to a sense of “double ignominy” by first experiencing that people choose not to include the husband with dementia in such a conversation, and then by participating in the exclusion of their partner – both of which lead to a sense of humiliation in these women in their roles as both wife and as caregiver.

The wives were also more likely to feel a sense of self-deprecation in a situation that makes their children worry about them. One of the women expresses this as:

… our children … they are just as desperate as me, in a way … but we said that they should live their lives … they should, so Dad is Dad, I am me … they should handle their everyday lives, they should live their lives, they should take care of their children, they shouldn’t have to think about sacrificing anything for us, they shouldn’t have an obligation that they must step in or help … or be present … or have to call at this time and this often … as we say to them: “Live your lives, we know that you are thinking of us, and we know that you are there.” (Sarah)

The wives don’t want to be a concern or a burden to their children. For some of these women, interrupting them and their families’ everyday lives make them feel guilty, which they then try to prevent as this also results in feeling dignity humiliation.

Discussion

Our findings can help us understand key sources of dignity humiliation among wives who care for a husband living with dementia at home. According to Baillie et al. (Citation2008), dignity is experienced through the way people think, feel and behave in relation to their sense of worth and value, about both themselves and others. From this perspective, people can experience dignity humiliation when they encounter degrading attitudes and behaviors of others when these are personally directed at the person, reducing their sense of self-worth. Furthermore, there seems to be a common understanding that there is an intimate relationship between notions of human dignity and humiliation, in which humiliation is perceived as an injury to a person’s dignity (Statman, Citation2000). Being humiliated can be understood as being “stripped of one’s dignity” (Gilbert, Citation1997, p. 133), or experiencing a “loss of control” following “a painful sense of loss of dignity” (Margalit, Citation1996, p. 115).

In this present study, our findings show that experiences of interpersonal dignity humiliation arise when the wives face indifference, curiosity and disrespectful attitudes of other people. In contrast, experiencing that they have been truly understood by others has been found to be a dignity-preserving source for this group of caregiving wives (Tranvåg et al., Citation2019). True understanding thus seems to be a key foundation when it comes to preventing dignity humiliation. In her theory of suffering and theory of caritative caring, Eriksson (Citation2006, Citation2018; Bergbom et al., Citation2021; Lindström et al., Citation2018) describe how human dignity and dignity humiliation can be understood. Eriksson’s two-dimensional notion of human dignity provided the basis of our theoretical framework. First, in line with the Declaration of Human Rights (United Nations, Citation1948), the inherent, absolute dignity of each human being, granted by virtue of being human, that is inalienable and cannot be reduced, lost or taken away. Second, a subjective experience of dignity that relates to each person’s sense of self-worth and worthiness in relation to others; that is, a relative sense of dignity that is changeable, depending on the relational interactions that occur in one’s everyday life. As such, relative dignity can be confirmed and supported, but also weakened or dismantled by sources in one’s life that humiliate them as an individual. Overall then, we believe that an increased knowledge of the absolute and relative dignity of all human beings among the general population, and particularly among HCPs of different professions, could contribute to making “dignity” a meaningful term to be used in our everyday language. Through our findings in this present study, we argue that by gaining a true understanding of what human dignity entails, as a phenomenon that occurs in everyone’s everyday lives, we could nurture the human potential to promote what is good and prevent that which isn’t when interacting with others.

Previously, Tranvåg et al. (Citation2015) found that respect and recognition from one’s social network serves as an external source that can both confirm and preserve a person’s subjective experience of dignity in their daily life – or to use Eriksson’s term in this context; her relative dignity (Eriksson, Citation2006, Citation2018; Lindström et al., Citation2018). Thus, educating people and HCPs as to what dignity is, as well as how to prevent dignity humiliation, is vital. National interventions like the ‘Dignity in Care’ campaign in the UK (National Dignity Council, Citationn.d.), and the Norwegian ‘Regulation for a Dignified Care for the Elderly’ (Norwegian Ministry of Health & Care Services, Citation2010), are of great importance. This can also be said of the international work of organizations like Global Dignity (Citation2021). All of these measures aim to promote dignity in care, and as such contribute to an increased awareness among the public and HCPs awareness as to how to preserve dignity in the interactions we all have throughout lives.

Our finding also show that the caregiving wives can experience interpersonal dignity humiliation when they require assistance by the healthcare services, and when they encounter incompassionate treatment by HCPs. This is both crucial and alarming; healthcare services that lack compassion contribute to the humiliation of the caregivers’ relative, changeable dignity – a perspective we argue that HCPs should be more aware of and prioritize in their work, which would then help to build a foundation for a sound dignity-preserving approach across interdisciplinary healthcare services. Genuine interest, compassion, and being a respected dialogue partner, are all qualities of care that help to preserve the dignity of the wives caring for a husband with dementia at home (Tranvåg et al., Citation2019). Such values are genuine and should therefore be a foundation for the act of care. However, our findings in this present study show that the wives experience that understanding of the worth of such values among HCPs sometimes is lacking. When the wives feel a sense of apathy in their interactions with HCPs – such as when HCPs neglect their efforts, perspectives and needs as wives and caregivers – this results in them feeling ignored and degraded. In addition to this, Clemmensen et al. (Citation2021) identified and described that while the wives hope that they will be acknowledged by HCPs, they often feel that they are overlooked and not given the attention they need. Rather than receiving compassionate care, the wives instead experience the burden of what can be called “professional uncaring” at the hands of HCPs that the wives had hoped and believed would support them. This is then a burden that is added to their already difficult life situation. In her theory of suffering, Eriksson (Citation2006, Citation2018; Lindström et al., Citation2018; Bergbom et al., Citation2021) describes that the humiliation of human beings in need of care by HCPs does happen. When HCPs are causing dignity humiliation by making a person feel as if she is being condemned or punished, this can be understood as suffering related to care – of which humiliation of the person’s dignity is the most frequent form. To prevent dignity humiliation, suffering related to care must be replaced by true forms of care. As the caritative approach to caring prioritizes love, mercy and compassion, this ontological view has the potential to influence human perspectives and the understanding of human dignity, which can in turn change people’s attitudes and behaviors in everyday relational interactions. Aiming to avoid dignity humiliation therefore holds great potential for preserving the relative dignity of another, in this case the caregiving wives, which in this case would be evident in the recognition of their inherent, absolute dignity – an acknowledgment of the equal worth of all human beings.

Experiencing genuine interest and compassion from HCPs, and feeling their acknowledgement and encouragement, can play a crucial role in preserving the dignity of wives caring for a home-dwelling husband with dementia (Tranvåg et al., Citation2019). This active approach in which the HCPs properly listen to the wives would replace the current “I know best-attitude”. The very act of turning to another human being is creative (Lindström, Citation1994). As Eriksson states this can be perceived as an invitation to be open with them, one based on respect and compassion for the other (Lindström et al., Citation2018). Being a respected equal in such dialogue has been found to serve as a vital foundation for these caregiving wives in their being able to experience such interactions with HCPs as dignity-preserving (Tranvåg et al., Citation2019). Even as early as 1859, Søren Kierkegaard described that the art of helping is based on ensuring one maintains a humble attitude in the way one helps others, in that “if one is truly to succeed in leading a person to a specific place, one must first and foremost take care to find him where he is and begin there” (Kierkegaard, Citation2000, p. 460). From this perspective, we can see how the ability and willingness of HCPs to actively try to gain a true understanding of the wives’ situations could be the key to achieving true caring. New understandings arise when making the effort to understand the perspectives of the other. We also argue that when this approach to caring is adopted, the foundation that HCPs base their professional ethics on can expand, such that they can learn from Eriksson’s mantra of caring ethics: “I was there, I saw, I witnessed, and became responsible” (Eriksson, Citation2013, p. 70). In this context, this would incorporate their being responsible for seeing, understanding and caring for women who care for a husband with dementia at home.

Importantly, in this study we also found that the caregiving wives sometimes experiences that they are failing at the system-level, in that the municipal healthcare services are not offering services that help promote a meaningful everyday life for their spouses with dementia. Experiencing this lack of balance when it comes to obtaining the same status and rights as patients and family caregivers living with diseases of a “higher status”, results in experiencing injustice and dignity humiliation. We argue that developing a caring culture based on the above premises for true caring is vital as it would help to establish a sound foundation for non-humiliating interactions between HCPs and caregiving wives, that is; promoting a dignity-preserving approach to professional caring practice. It is essential that more measures to achieve this are introduced and supported, such as national incentives implemented by the authorities to promote the status of dementia, as well as campaigns to develop municipal healthcare services for persons with dementia and their family caregivers that are of equal quality as the services currently for other healthcare receivers. Moreover, as recommended by WHO (Citation2017), it is important that future educational programs in healthcare specifically focus on the experiences and needs of family caregivers of persons with dementia, as demonstrated by the wives who participated in this present study.

On the intrapersonal level, we found that dignity humiliation is experienced by the wives when living in what can be understood as a self-deprecative life-situation, one characterized by voluntary suppression or denial of one’s own interests or desires. According to Eriksson (Citation2018) self-inflicted humiliation of one’s dignity occurs when the human being, in this case the caregiving wives, do not listen to their own inner voice. Being healthy means being whole, experiencing oneself as a whole person. Women in this study are aware of their basic values. Realizing that they need help from the municipal healthcare services to provide the husband with the care he needs leads them to experience a conflict with their basic values, resulting in their reporting that they feel they have a troubled conscience. As described by Hammar et al. (Citation2021), wives caring for a husband with dementia at home may experience stress, loneliness and depression. This is triggered by a sense of demoralization, first and foremost because they have had to take on this role of carer, someone who is always on duty, which then contributes to their experiencing negative thoughts and painful emotions, and occasionally wanting to die, or that their partner would die.

In another recent study, Thorsen and Johannessen (Citation2021) found that wives caring for a husband with dementia may feel guilty and wicked in the process of having to accept the municipal services’ offer of a nursing home placement for the husband. Some women who participated in our study felt ambivalence and were uncomfortable asking for help in caring for their spouse. Not being able to give the same care and help to her husband, and live as they did before, can feel like a loss of dignity. Some wives also experience a “double ignominy” when they realize that people are not including the husband in conversations, and then find themselves taking part in the exclusion of their partner in these interactions. We therefore argue that HCPs should be aware of this aspect of self-inflicted dignity humiliation and, when needed, offer the wife guidance on how to cope with these situations that could help to preserve the dignity for all parties.

Eriksson (Citation1997) states that human beings experiences dignity when they are able to express one’s own human capacity, and when they are available to serve and be there for another. When the person is deprived of the ability to care and the responsibility to act accordingly, their sense of dignity is humiliated. In the case of some of these women, this is a form of double humiliation; on the one hand, they feel that they are acting against their own basic values, while on the other hand, they experience a loss of freedom or feel powerlessness and sad because the level of their freedom has changed. Eriksson (Citation1997) refers to Lindborg (Citation1974), who claims that being able to experience dignity is also affected by the person’s opportunity to have that freedom to make their own choices in life, as well as the right to protect oneself from infringement.

Considering this, it is of utmost importance that HCPs are aware of, respect and have compassion for painful feelings of insecurity, shortcomings, despair and guilt that these wives experience in their roles as caregivers, and that they understand how such inner burdens further weaken these caregiving women’s intrapersonal sense of dignity. According to Eriksson (Citation1997), experiencing the feeling that you are a person of value, gives one the strength and courage to be a good neighbor to others, as well as providing that necessary foundation to be capable of experience compassion and love. The author even states that this is the core of being able to care for oneself and for others. Nåden and Eriksson (Citation2004) underline that a thoroughly moral attitude and demeanor is vital in care to achieve the preservation of humanness and human dignity. It is not only important for those in need of help, in our case the women who care for their husbands, but also for the HCPs, because humiliating those who seek help, also results in the humiliation of their own dignity (Nåden & Eriksson, Citation2004). The vulnerable and suffering women need to be seen and validated as human beings who are going through a difficult life situation. This validation is genuine if it is consistent and includes an open invitation that doesn’t presume anything about, but rather accepts the other person and everything they are presenting to the listener, such that the HCPs are also aware of and in contact with the deepest part of themselves (Nåden & Eriksson, Citation2000). This thus realizes Eriksson’s statement that suffering is the point at which caring begins (Eriksson, Citation1992).

As these women have long cared for their husbands with progressive dementia (World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International, Citation2012), the burdensome feelings and intrapersonal experiences of self-deprecation some spouses experience when in need of help and support from HCPs, supposedly more or less in silence, should be acknowledged and taken seriously. Suffering must be acknowledged as such, not as a certain state of being (Eriksson, Citation1992). What is needed then is a genuine validation that can only be achieved in an encounter that is characterized by mutual respect and esteem, and in which deep solidarity and closeness are integral factors (Nåden & Eriksson, Citation2002). Following this line of thought, the deepest ethical motive in all caring, which involves respect for the absolute dignity of the human being, and the inner freedom and responsibility for one’s own and others’ lives (Eriksson, Citation2002), will then be fulfilled for both parties. Having these ideals in mind, the opportunities are present for these vulnerable women to be able to feel both relief and power in caring for their husbands and for their journey ahead together. The importance of offering the caregiving wives sufficient emotional support in order to alleviate their experience of dignity humiliation and also enhance their resilience and well-being, is also described as critical by Johansson et al. (Citation2021). Furthermore, Chiari et al. (Citation2021) suggest that direct actions such as strengthening the caregiver’s social network and shortening the current delay in diagnosing the partner’s dementia condition could help to reduce the caregiver’s level of psychological distress and burdens, as would indirect actions such as financial support and increasing the number of days off work the caregiver receives.

Our findings in this present study show that dignity humiliation negatively affects the well-being of women who care for a husband with dementia at home. As emphasized by WHO (Citation2017) in their Global Action Plan on the Public Health Response to Dementia 2017–2025, there is a huge number of female family caregivers around the world, and they should have access to services and support that are tailored to their needs, as this can effectively help alleviate the mental, social and physical demands that come with their caregiver role. In addition, Erol et al. (Citation2016) address the importance of establishing health policies that would enhance the skills and knowledge of the interdisciplinary healthcare workforce in how they support women who care for a person with dementia. We support these perspectives and argue that our findings add new knowledge about key sources that lead to dignity humiliation among wives who care for a husband with dementia at home – knowledge that should be integrated and employed to improve interdisciplinary caring practices and policy development specifically relevant to this group of female caregivers.

Methodological considerations and study limitations

The data obtained in this study originated from a participant group not previously consulted about key sources that lead to their experiences of dignity humiliation. However, several study limitations should be addressed: Within the 24-month timeframe allocated for participant recruitment, only six wives consented to participate in the study. A larger sample would most likely have added further depth to the data collected. Restrictions in extending the recruitment period excluded this option. However, qualitative studies can, even with small samples, generate new, in-depth understandings of phenomena that we currently have limited knowledge of (Brinkmann, Citation2015). The wives had been caregivers for a relatively short period of time, ranging from six months to three years since their husbands had first been diagnosed. Additionally, the husbands had been diagnosed as having mild to moderate dementia. Thus, the experiences the wives report may change over time, as the disease progresses. The wives who chose not to participate may have had other feelings and experiences than those who chose to participate. We understand that there is a possibility that other female partners – married, unmarried, gay or from other, diverse groups, may experience different types of dignity humiliation as a partner of a person with dementia. Future research should therefore study the experience of dignity humiliation of caregiving wives’ in more severe stages of dementia, as well as caregiving women in other countries and communities. Moreover, dignity humiliation experienced by male caregivers and people in non-heteronormative relationships deserve equal consideration.

Conclusion

Our findings provide an insight into how wives who are responsible for caring for their husbands, whom have dementia and live at home, experience dignity humiliation through interpersonal experiences of people’s indifference, curiosity and disrespectful attitudes, interpersonal experiences of limited access to healthcare services and incompassionate treatment by HCPs, and intrapersonal experiences of self-deprecation. These key sources create wounds among the women which are both demeaning and painful. The women who took part in the study provide in-depth knowledge through their reports of the negative actions and attitudes they experience of those around them, as well as those of the incompassionate HCPs, who ignore their efforts, perspectives and needs as wives and caregivers, making them feel disrespected and degraded. This adds another burden on top of the already difficult situations they are living with. Seen from an interdisciplinary healthcare perspective of wanting to prevent dignity humiliation, suffering related to care must be replaced by true caring by all parties. Actively working to avoid dignity humiliation holds great potential for preserving the relative dignity of the women, and this lies in the recognition of the inherent, absolute dignity – acknowledging the equal worth of all human beings. We also argue that when seeking to understand the other, the professional ethics of which the work of HCPs is based on can be enhanced – learning from the mantra of caring ethics employed by Eriksson (Citation2013, p. 70): “I was there, I saw, I witnessed, and I became responsible”. In this context, they can take on the responsibility for seeing, understanding and caring for women who care for a husband with dementia.

Competing interests

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank our participants’ entrusting engagement in sharing their experiences and perceptions with us.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2015). Women and dementia. A global research review. https://www.alzint.org/resource/women-and-dementia-a-global-research-review/

- Alzheimer’s Society. (2014). Dementia UK: Second edition – Overview. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/59437/1/Dementia_UK_Second_edition_-_Overview.pdf

- Baillie, L., Gallagher, A., & Wainwright, P. (2008). Defending dignity: Challenges and opportunities. Royal College of Nursing. https://www.dignityincare.org.uk/_assets/RCN_Digntiy_at_the_heart_of_everything_we_do.pdf

- Bergbom, I., Nåden, D., & Nyström, L. (2021, October 5). Katie Eriksson’s caring theories. Part 1. The caritative caring theory, the multidemensional heath theory and the theory of human suffering. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 00, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13036

- Boylstein, C., & Hayes, J. (2012). Reconstructing marital closeness while caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s. Journal of Family Issues, 33(5), 584–612. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11416449

- Brinkmann, S. (2015). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Chiari, A., Pistoresi, B., Galli, C., Tondelli, M., Vinceti, G., Molinari, M. A., Addabbo, T., & Zamboni, G. (2021). Determinants of caregiver burden in early-onset Dementia. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders Extra, 11(2), 189–197. https://doi.org/10.1159/000516585

- Clemmensen, T. H., Lauridsen, H. H., Andersen-Ranberg, K., & Kaae, H. (2021). ‘I know his needs better than my own’ – carers’ support needs when caring for a person with dementia. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 35(2), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12875

- Dunham, C. C., & Cannon, J. H. (2008). They’re still in control enough to be in control”: Paradox of power in dementia caregiving. Journal of Aging Studies, 22(1), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2007.02.003

- Eriksson, K. (1992). Nursing: The caring practice ‘being there. In D. A. Gaut (Ed.), The presence of caring in nursing (pp. 201–210). National League for Nursing Press.

- Eriksson, K. (1997). Caring, spirituality and suffering. In M. S. Roach (Ed.) Caring from the heart. The convergence of caring and spirituality (pp. 68–84). Paulist Press.

- Eriksson, K. (2002). Caring science in a new key. Nursing Science Quarterly, 15(1), 61–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/089431840201500110

- Eriksson, K. (2006). The suffering human being. Nordic Studies Press.

- Eriksson, K. (2013). Jäg var där, jag såg, jag vittnade och jag blev ansvarlig – den vårdande etikens mantra [I was there, I saw, I witnessed and became responsible – the mantra of caring ethos]. In H. Alvsvåg, Å. Bergland, & O. Førland (Eds.), Nødvendige omveier [Necessary detours] (pp. 69–85). Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Eriksson, K. (2018). Vårdvetenskap: vetenskapen om vårdandet – Om det tidlösa i tiden. Samlingsverk av Katie Eriksson. Caring Science. [The science about the Essence of Care About the Timeless in Time. A collection by Katie Eriksson]. Liber AB.

- Erol, R., Brooker, D., & Peel, E. (2016). The impact of dementia on women internationally: An integrative review. Health Care for Women International, 37(12), 1320–1341. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2016.1219357

- Friedemann, M.-L., & Buckwalter, K. C. (2014). Family caregiver role and burden relatedto gender and family relationships. Journal of Family Nursing, 20(3), 313–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074840714532715

- Gadamer, H. G. (2004). Truth and method (2nd rev. ed.). Bloomsbury Academic.

- Gilbert, P. (1997). The evolution of social attractiveness and its role in shame, humiliation, guilt and therapy. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(2), 113–147. https://bpspsychub.onlinelibrary.wiley.com https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01893.x

- Global Dignity. (2021). Global dignity day. https://globaldignity.org/global-dignity-day/

- Guba, E. G., Lincoln, Y. S., & Denzin, N. K. (1994). Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 105–117) Sage.

- Hammar, L. M., Williams, C. L., Meranius, M. S., & McKee, K. (2021). Being ‘alone’ striving for belonging and adaptation in a new reality – The experiences of spouse carers of persons with dementia. Dementia, 20(1), 273–290. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301219879343

- Hiles, D., & Čermák, I. (2007, July 3–6). Qualitative research: Transparency and narrative oriented inquiry. Paper presented at 10th ECP, Prague, Czech Republic. https://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.492.634&rep=rep1&type=pdf

- Johansson, M. F., McKee, K. J., Dahlberg, L., Williams, C. L., Summer Meranius, M., Hanson, E., Magnusson, L., Ekman, B., & Marmstål Hammar, L. (2021). A comparison of spouse and non-spouse carers of people with dementia: a descriptive analysis of Swedish national survey data. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 338. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02264-0

- Kierkegaard, S. (2000). On my work as an author (August 1851). The point of view for my work as an author (written 1848, published 1859). In H. V. Hong & E. H. Hong (Eds.), The essential Kierkegaard (pp. 460). Princeton University Press.

- Kim, H., Chang, M., Rose, K., & Kim, S. (2012). Predictors of caregiver burden in caregivers of individuals with dementia. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 68(4), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2011.05787.x

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage.

- Lindborg, R. (Ed.) (1974). Om människans värdighet : med några kapitel om humanism och mystik och naturfilosofi under renässansen/Giovanni Pico della Mirandola [About human dignity: with some chapters on humanism and mysticism and natural philosophy during the Renaissance/Giovanni Pico della Mirandola]. In Skrifter utgivna av Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund (Vol. 71). Science Society in Lund.

- Lindström, U. Å. (1994). Psykiatrisk vårdlära [Textbook in psychiatric care]. Liber Utbildning.

- Lindström, U. Å., Lindholm, L., & Zetterlund, J. E. (2018). Theory of caritative caring. In M. R. Alligood (Ed.), Nursing theorists and their work (9th ed., pp. 140–163). Elsevier.

- Margalit, A. (1996). The decent society (pp. 115). Harvard University Press.

- Nåden, D., & Eriksson, K. (2000). The phenomenon of confirmation: An aspect of nursing as an art. International Journal of Human Caring, 4(3), 23–28. https://doi.org/10.20467/1091-5710.4.3.23

- Nåden, D., & Eriksson, K. (2002). Encounter – A fundamental category of nursing as an art. International Journal of Human Caring, 6(1), 34–40. https://doi.org/10.20467/1091-5710.6.1.34

- Nåden, D., & Eriksson, K. (2004). Understanding the importance of values and moral attitudes in nursing care in preserving human dignity. Nursing Science Quarterly, 17(1), 86–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894318403260652

- National Dignity Council (UK). (n.d.). Dignity in care campaign. https://www.dignityincare.org.uk/About/National_Dignity_Council/

- Norwegian Ministry of Health and Care Services. (2010). Verdighetsgarantiforskriften, Forskrift om en verdig eldreomsorg (verdighetsgarantien) [Regulation concerning dignified care for older people (The dignity guarantee)]. https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2010-11-12-1426

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. (2010). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice. Wolters Kluwer/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Potgieter, J. C., & Heyns, P. M. (2006). Caring for a spouse with Alzheimer’s disease: Stressors and strengths. South African Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 547–563. https://doi.org/10.1177/008124630603600307

- Sagbakken, M., Nåden, D., Ulstein, I., Kvaal, K., Langhammer, B., & Rognstad, M.-K. (2017). Dignity in people with frontotemporal dementia and similar disorders - a qualitative study of the perspective of family caregivers. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1), 432. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2378-x

- Statman, D. (2000). Humiliation, dignity and self-respect. Philosophical Psychology, 13(4), 523–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515080020007643

- Thorsen, K., & Johannessen, A. (2021). Metaphors for the meaning of caring for a spouse with dementia. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 14, 181–195. https://doi.org/10.2147/JMDH.S289104

- Tranvåg, O., Nåden, D., & Gallagher, A. (2019). Dignity work of older women caring for a Husband with dementia at home. Health Care for Women International, 40(10), 1047–1069. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2019.1578780

- Tranvåg, O., Petersen, K. A., & Nåden, D. (2015). Relational interactions preserving dignity experience: Perceptions of persons living with dementia. Nursing Ethics, 22(5), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014549882

- Tranvåg, O., Petersen, K. A., & Nåden, D. (2016). Crucial dimensions constituting dignity experience in persons living with dementia. Dementia (London, England), 15(4), 578–595. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301214529783

- United Nations. (1948). Universal declaration of human rights. https://www.un.org/en/about-us/universal-declaration-of-human-rights

- van Gennip, I. E., Pasman, H. W. P., Oosterveld-Vlug, M. G., Willems, D. L., & Onwuteaka-Philipsen, B. D. (2016). How dementia affects personal dignity: A qualitative study on the perspective of individuals with mild to moderate dementia. The Journals of Gerontology Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 71(3), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbu137

- World Health Organization and Alzheimer’s Disease International. (2012). Dementia: A public health priority. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/dementia-a-public-health-priority

- World Health Organization. (2017). Global action plan on the public health response to dementia 2017-2025. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/259615/9789241513487-eng.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y

- World Health Organization. (2021). Dementia. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/