Abstract

Our intent was to explore if maternal anxiety, depression, reflective functioning and level of attachment significantly changed after the Building Bonds and Attachment Service (BABS) Intervention. We measured outcomes for 46 at risk mothers via HADS; MAAS; MPAS and P-PRFQ. Our findings, triangulated with 32 semi structured interviews identified that BABS intervention made a significant difference to participants who were admitted during the antenatal period (Pregnant group: depression 9.63[CI:7.63–11.63; p < 0.001]; anxiety 9.40[CI: 7.56–11.24]; p < 0.001]; reflective functioning 30.78[CI:24.84–36.72; p < 0.001] and maternal attachment 8.78[CI:4.08–13.48]; p 0.001). Suicidal contemplation was prevented for two women. Our conclusions explained the service made a significant difference to the lives of mothers between baseline and post intervention for pregnant mothers with anxiety and depression who struggled to bond with their baby. Appropriate referral may help to increase accessibility to those who may benefit most. Further research needs to test if this care model would be acceptable to culturally diverse populations.

Researchers recognize that maternal-infant attachment barriers are experienced globally (World Bank, Citation2021) and that global instability increases the need to understand more about attachment within each nation (Cassidy et al., Citation2013). We wanted to understand how the Building Bonds and Attachment Service (BABS) impacted mothers who were deemed to be at risk of developing a poor relationship with their baby by examining the relationship between maternal anxiety, depression, reflective functioning and level of attachment. The setting for this research was in an area of high deprivation in North West England where incidence of child abuse or domestic violence is recorded. World Health Organisation (Citation2006) raise awareness of how positive maternal attachment influences the prevention of child abuse. Consequently, it is important to recognize that the sociocultural circumstances of the mothers, represented in this research, are replicable in global settings where; mothers are anxious or depressed, live with domestic violence, cope with single parenting, were a looked after child in the past, have psychological or psychiatric histories or a low level of education and who have experienced poor maternal experiences with their own mothers, which was reflected in this study. Therefore, this evidence raises awareness internationally, about a potential model of care to support at risk mothers to bond with their infants. We present a model of care that identifies the potential for how professional disciplines can be bridged to enhance maternal wellbeing. Our aim is that students who need to learn more about maternal attachment will develop a deeper understanding of complexity associated with the important attachment and bonding process for at risk mothers and we discuss how methodological considerations may assist researchers to design future research.

Background

Secure and sensitive maternal-infant bonding is crucial to the development of the child. The first 1001 days (from conception to age two) is recognized as a critical phase during which the foundations of a child’s social, emotional, physical, mental and neurological development are determined (Evertz et al., Citation2020; Leadsom et al., Citation2014). Secure attachment (Type B) was identified by Ainsworth et al. (1978 cited in Holmes & Farnfield, Citation2014, p. 2) to be where infants felt confident that their mothers would meet their needs. However, anxious/ambivalent (Type C: where the child does not feel secure), and anxious/avoidant (Type A: where the child does not seek contact with their mother and the mother may be insensitive or rejecting of their needs) or where there are disorganized/chaotic (Type D) (Main and Soloman (1990 cited in Duschinsky & Solomon, Citation2017, p. 525) attachment styles are present in society globally. Çinar and Öztürk (Citation2014) and Keller (Citation2018) recognized that maternal attachment style may vary in different cultures and it is important to acknowledge that these seminal texts were generated from white, western, middle class participants. Therefore, researchers need to question if the findings are transferrable to international settings as there may be situations in which the insecure attachment patterns are adaptive and considered acceptable in certain cultures (Harwood et al., Citation2000).

To understand more about maternal-infant attachment style, it is important to consider the reasons why negative styles of behavior develop. Researchers suggest that caregivers who display atypical behaviors often have a history of unresolved emotional, physical or sexual trauma where they were traumatized (Cyr et al., Citation2010). Cyr et al. (Citation2010) examined if, disorganization related to maltreatment, impacted attachment differently than socioeconomic risk. Their meta-analysis was based on 59 samples of non-maltreated high-risk children (n = 4,336) and 10 samples with maltreated children (n = 456). Their findings indicated that, child attachment insecurity and attachment disorganization, were strongly impacted by maltreating parental behavior and by cumulative socioeconomic risk as opposed to singular risk. Cumulative risk linked to Atypical maltreating parental behavior has the potential to create transgenerational maltreatment and can have a detrimental impact on parenting (Bowlby, Citation1969; Citation1998; Bowlby et al., Citation1965). According to Bowlby (Citation1998), the movement to poor transgenerational attachment style begins when infants develop an internal working model of attachment as a result of their early interaction with caregivers. This internal working model influences the child’s internal representations of self, others and the world. Therefore, there is potential for an internal working model to feed forward from person to person to have a transgenerational influence on people and society (Cassidy & Shaver, Citation2016; Evertz et al., Citation2020).

Maltreatment overtime became the focus for Muzik et al. (Citation2013) who involved two groups of mothers at 6 weeks, 4 months and 6 months postnatal. Mothers who experienced childhood abuse before 16 years old (n = 97) and those who did not report any, participated as a comparison group (n = 53). The sample size was small and over representation of the abuse group leads readers to cautious interpretation of the findings, however, their study involved a “hard to reach” group of mothers and the findings are valuable for our study involving mothers who were at risk from; domestic violence, diagnosed mental health conditions, poor socioeconomic conditions, being a looked after child themselves or being known to social services.

Muzik et al. (Citation2013) agreed with previous evidence by Bowlby (Citation1998) and Ainsworth et al. (1978 cited in Holmes & Farnfield, Citation2014) to explain that childhood exposure to abuse and neglect resulted in increased risk of bonding difficulties and psychopathology. The authors explained that even though depression and socioeconomic risk were controlled for, the findings indicated that childhood abuse and neglect in the past, significantly (p = 0.00) increased the risk of maternal depression and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which suggested that psychopathology, and not the maltreatment history, created the greatest risk for bonding (Muzik et al., Citation2013). Importantly, Muzik et al. (Citation2013) suggested that overtime, mothers with psychopathology and who demonstrated maltreatment, could develop close bonds early in the postnatal period, independent of emotional disturbance, which indicated the potential for mothers to grow closer to their babies despite emotional disturbance.

One of the most important clinical approaches to support maternal-infant bonding revolves around Parent Infant or Mother Infant Psychotherapy (PIP/MIP). PIP/MIP therapy involves clinicians using a tool box of strategies based around; video interaction analysis, listening/talking, the use of a particular psychodynamic model as a framework, targeting the mother-infant transference, or mother-psychotherapist transference or targeting mother internal working models and representations (Huang et al., Citation2020). Alternatively, clinicians may focus on raising awareness about remembrance where the intent is to reduce the presence of ghosts in the nursery (Fraiberg et al., Citation1975). Clinicians can deliver therapy to the mother, the maternal dyad or both parents and the infant. It is possible to provide therapy in groups or to individuals, in any setting (home, community clinic or hospital). Participants in therapy may have mental ill health, or psychiatric pathology and clinicians can use multiple measures to inform treatment or signpost for supportive approaches.

Evidence to support PIP was developed by Barlow et al. (Citation2015, Citation2016) and used a meta-analysis of eight studies (n = 846 randomized participants) to compare PIP with a no-treatment control groups or with other types of treatment. Parents included in the study had infants of 24 months or less at entry. Their findings indicated that there was an increase in infants who were defined as securely attached following PIP (RR 8.93, 95% CI 1.25 to 63.70, 2 studies; n = 168). However, their results emerged from very low-quality evidence and revolved around the inclusion criteria of only one standardized measure of parental or infant functioning, whereas we included four in our study (see measures section). To investigate MIP, Huang et al. (Citation2020) systematically reviewed 13 studies via a rigorous inclusion criterion and found that there was a short-term effect (−.25, 95% CI −40, −0.09) with a risk ratio of 0.71, 96% CI 0.55, 0.91. The long-term effect of MIP did not appear to improve maternal mood, mother-infant interaction and infant attachment. The authors suggested that concepts such as intensity or frequency of interaction, trimester of pregnancy and the type of MIP influenced the findings. In corroboration with Barlow et al. (Citation2016), Huang et al. (Citation2020) recommended future research to be important. In the light of this evidence we explored how one model of care, in a deprived area of the UK, based around a specialist midwife and psychologist care model in BABS made a difference to maternal-infant attachment. Therefore, this study was designed around three research questions where we asked:

Do mothers’ level of anxiety, depression and reflective functioning change when they receive support from the Building Attachment & Bonds Service (BABS) between Time Point one (TP1) (Admission) and TP 2 (Discharge)?

What was the relationship between mothers’ anxiety, depression, and reflective functioning on mother-child attachment between TP1 and TP2?

What were mother’s experience of being enrolled in BABS?

Methods

Study design and procedure

We used an exploratory, longitudinal mixed methods design (Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018; O’Caithain et al., Citation2010) that permitted maternal changes to be investigated between Time Point one (TP1: Admission) and TP2 (Discharge) after BABS intervention. Ethical approval for recruitment was gained from The NHS Research Authority (Reference: IRAS 241481) and The Faculty of Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee (Reference: CYPF 9). Mothers understood that all data was to be kept confidential, their identity would not be disclosed and that their comments would be represented in dissemination. The inclusion criteria included mothers above 16 years of age, referred to BABS by community midwives after demonstrating bonding difficulties, who had a child was under 24 months of age or under and who were English speaking.

Recruitment took place in the second highest deprived area of North West England, between November 1st, 2018 and February 28th, 2020. There was a base line assessment via 4 standardized measures at TP1 which was compared to findings at TP2. The project team for this study were divided into the therapeutic team (who collected mother’s completed measures and treated as was routine practice (LM;CD;GD) and the research team (who gained funding, ethical approval, data managed, ran and analyzed the study independently (LB;PG;AF). Mothers were assessed as being highly vulnerable and at risk (NICE, Citation2010; see Participant Characteristics). Therefore, to protect the therapeutic relationship the first meeting with the clinician focused on the therapeutic relationship only. At the second meeting clinicians in the therapeutic team provided potential participants with an information sheet. At the consent to participate meeting mothers were invited to share the routinely collected questionnaire data with the research team and/or consent to be interviewed near to discharge.

Table 1. Study participant characteristics.

Description of the intervention

The Building Attachment and Bonds Service (BABS) is a specialist parent infant mental health service (PIMHS) which offers psychotherapeutic, parent-infant interventions which include: parent infant psychotherapy (PIP – Ghosts in the Nursery), video interaction guidance (VIG), systemic/family therapy interventions, mindfulness based interventions and attachment based therapies. Mothers are referred by the midwifery team in the local area. During the study period, the BABS therapeutic team included one psychologist (LM) and two specialist midwives (CD;AW). Participants received enhanced midwifery care which reflected a 50% increased clinical time allocation compared to routine midwifery practice in the UK as guided by NICE (Citation2021). The number of visits in our study were determined by the needs of the participant. Mothers were encouraged to share their concerns about anything that created a barrier to bonding.

Measures

All participants completed the following tests:

Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith, Citation1983) is a 14-item validated (Crawford et al., Citation2001; Herrmann, Citation1997) questionnaire that can be completed in two minutes. The tool separates psychological concepts related to anxiety and depression. Both anxiety and depression subscales have good internal consistency, with values of Cronbach’s alpha (α) evidenced at 0.80 and 0.76, respectively (Mykletun et al., Citation2001). The combined score represents degree of psychological distress and was calculated by adding anxiety and depression measures together. Degrees of psychological distress were indicated by <7 normal, 8–10 mild, 11–14 moderate or 15> severe categories.

Maternal Antenatal Attachment Scale (MAAS) (Condon, Citation1993; Condon & Corkindale, Citation1997) is a 19 item self-report questionnaire assessing the quality and intensity of antenatal emotional attachment between the mother and fetus. The MAAS has good psychometric properties; high levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.79) and a test-retest reliability of 0.70 (Condon, Citation1993). Quality of attachment (represented by questions; 3,6,9,10,11,12,13,15,18,19) and time spent in attachment (or intensity of preoccupation represented by questions; 1,2,4,5,8,14,17,18) was measured. Scoring is 1–5 with 5 high attachment. Reverse scoring exists for questions; 1,3,5,6,7,9,10,12,15,16;18,19.

Maternal Postnatal Attachment Scale (MPAS) (Condon & Corkindale, Citation1998) is a 19 item self-report questionnaire that assesses the mother-to-infant attachment relationship postnatally. High levels of internal consistency (Cronbach’s α 0.78) and test-retest reliability (0.70) are reported. Quality of attachment (measured by questions; 3,4,5,6,7,10,14,18,19); absence of hostility (questions; 1,2,15,16,17) and pleasure in interaction (questions; 8,9,11,12,13) was measured. A score of one reflects low and five, high attachment. Questions 15, 16 and 18 have three categories therefore, scoring identified five as high, three as middle and a score of one as low. Questions; 7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14 are reverse scored. Total attachment score was used in clinical practice from 19 to 95. A score of 0–19 reflected that mothers would be referred on to relevant support services; 20–38 would involve targeted one to one work and 39+ that the mother could be part of group support.

The Prenatal Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire (P-PRFQ) (Pajulo et al., Citation2015) is a 14 item self-report measure that assesses reflective functioning within the prenatal period. Reflective function relates to an individual’s capacity to mentalize or visualize mental states in the self or the other and this capacity provides the parent with the ability to, “hold the child’s mental state in mind” (Slade, Citation2005, p. 269). In this study, the questionnaire was adapted for use in the postnatal period, as was suggested by the authors.

Statistical analysis

To our knowledge, there were no previous studies involving this model of care in this clinical setting to base a power calculation.

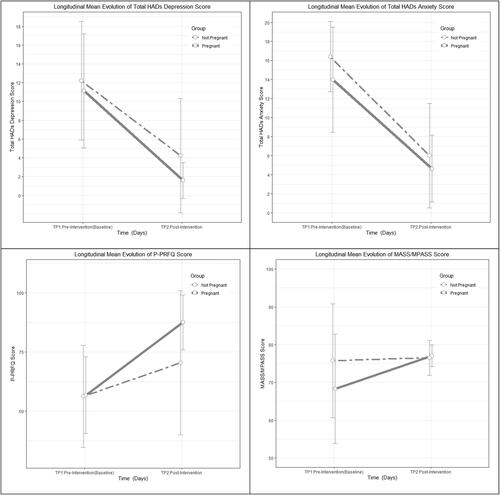

Quantitative data were analyzed by PG using IBM SPSS (Version 25). Longitudinal group mean profile plots (Verbeke & Molenberghs, Citation2000; : Mean Profile Plots) displayed the extent of variability of the continuous outcome variables with respect to time. Spearman’s rho statistic correlation coefficients (Altman, Citation1991; : rho correlation) were computed to capture the degree of association between maternal anxiety, depression, and reflective functioning on mother-child attachment at discharge from BABS and the. Profile plots were complemented by measures of mean, standard deviation, minimum and maximum statistics of the continuous outcomes to summarize data distribution characteristics at baseline (TP 1) and discharge (TP 2) (: Mean differences). A paired t-test (Goulden, Citation1956) compared difference in the means of each measure at admission and discharge. Given the longitudinal design of the study, an Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) (Cooper et al., Citation2018) model was fitted to account for the observed baseline variability of outcomes and allow for the adjustment of important maternal characteristics that could positively or negatively influence the results.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics for outcome scores by time, group, & mean differences.

Table 3. Spearman rho correlation coefficients between depression, anxiety, reflective functioning, and maternal attachment by time points.

Qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim by the researchers and included pauses and reference to outside noise to increase transparency (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Nowell et al., Citation2017). Researchers asked, for example, “What was your experience of BABS?,” “What has changed because of that experience?,” “How do you feel now?,” “What difference has BABS made to you and your family?.” Two researchers (LB;AF) independently analyzed and used NVivo (Version 12) to organize the data and analysis was supported via a vulnerability framework (Briscoe et al., Citation2016, p. 2339). Themes emerged from the data at different times and the development of findings was not linear. Researchers performed cross group analysis separately and the process helped to corroborate findings from mother’s individual interviews (25) with the findings from mothers who chose to have their partner present during the interview (5 participants only). Researchers discussed their interpretation during three iterations where consensus was reached.

Quantitative and qualitative data were valued equally (Creswell & Plano Clark, Citation2018) and synthesis emerged via the five-step process involved in framework analysis (Ritchie & Spencer, Citation1994; Spencer et al., Citation2003; Srivastava & Thompson, Citation2009). To enhance transparency in reporting mixed methods the CitationEQUATOR Network (2021) was accessed, and a check list informed the standard of reporting (Fetters & Molina-Azorin, Citation2019, p. 417).

Results

Description of participants

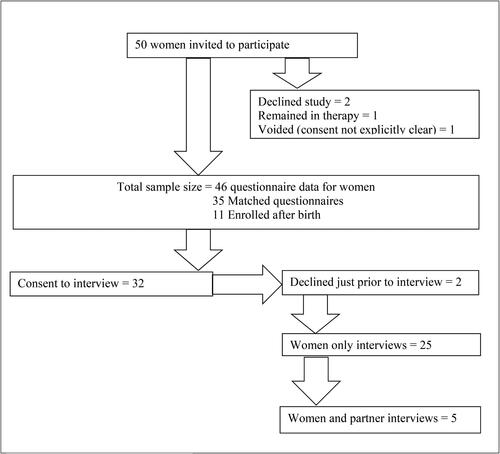

Thirty-six mothers were pregnant and ten were postnatal at recruitment (n = 46). Mean days in the study were 160 (SD 81; Range 66–435). Mean maternal age was 21–29 years and age range reflected; 10 mothers, 16–20 years; 20 mothers, 21–29; 14 mothers, 30–39 and one mother who was 40–49 (missing 1) (: Participant Characteristics). Forty-six mothers had 35 matched questionnaires across the antenatal-postnatal time span. Eleven mothers were enrolled postnatally. Thirty-two mothers agreed to an interview prior to discharge, two declined just prior to interview (: Participant Flow Chart).

Figure 2. Mean profile plots of Total HADs, Total Anxs, P-PRFQ, and MAAS/MPASS scores by pregnancy status group with ±1 SD at each time point.

identifies that the relationship status was single for the majority of participants (20, 43.5%). Twenty-six (56.5%) declared a previous psychological or psychiatric history and there was a low level of education recorded for 38 (82.6%).

For each of the 4 outcome measures, an ANCOVA model was fitted with each of the 10 patient characteristic variables together with number of days in the study and baseline outcome score. Out of the 10 patient characteristics, accommodation and pregnancy status at entry into study were significant for P-PRFQ; education and pregnancy status at entry into study were significant for HADs Depression; education was borderline significant for HADs Anxiety and none of the 10 patient characteristics variables were significant for MAAS-MPASS.

Quantitatively, : Mean Profile Plots, depict the mean change over time by pregnancy status groups. Overall, there was a significant change of p ≤ 0.001 for the better in depression, anxiety, and reflective functioning in the pregnant group. The change in the non-pregnant group for the same outcomes was not as highly significant and there was no significant change in maternal attachment for the non-pregnant group.

shows the number of mothers (n) in each pregnancy status group, the minimum, maximum, mean (standard deviation) of depression, anxiety, reflective functioning, and maternal attachment score outcomes at each time point. The mean differences showing the change in the score outcomes between time points by pregnancy status group is also given with a 95% confidence interval.

To explore the relationship between anxiety, depression, and reflective functioning on mother-child attachment at discharge from BABS used Spearman rho correlation coefficients between depression, anxiety, reflective functioning, and maternal attachment by Time Points. Highly significant (p ≤ 0.0001) Spearman rho correlation coefficients between depression and anxiety as well as reflective functioning and maternal attachment were observed at baseline (TP 1). The strong correlation between depression and anxiety remained strong and significant post intervention. However, at post-intervention (TP 2) the correlation between reflective functioning and maternal attachment was less than 0.5.

Quantitative and qualitative synthesis corroborated statistically significant findings that suggested depression and anxiety reduced after engagement with BABS. For example, Participant 20 (P20) expressed how BABS support for depression and PTSD made her feel less depressed and anxious and more able to keep her baby in mind which resulted in feeling less hostility during bonding and she said:

Because I have got post-natal depression and PTSD [the feelings] just took over…. so she’s [BABS clinician] been really helpful and obviously pointed me in the right direction and got the right support for me really… And I feel that my bond is much better with [the baby]. (P20, recruited PN; 112 study days)

P4 was recruited in the antenatal phase and her comments captured a perceived dramatic change that reflected a reduction in anxiety from severe to normal and from mild depression to normal:

I suffered a lot of abuse when I was a child and I didn’t really speak about it but I feel like since (BABS)….they’ve [BABS] changed my life dramatically…I’ve learned to speak if I’m worried or if anything’s on my mind …instead of bottling things up, which chews you up [television noise] and then next thing, goes on to self-destruct mode then! (P4, recruited AN; 299 study days)

The ability of the intervention to interrupt escalation of anxiety toward suicidal thoughts was explained by P29 explained:

I was in a really bad place, I went suicidal twice…I said to them, ‘I don’t want to be here I want to die; I don’t want to be here and if it weren’t for my kids I wouldn’t be here’. I ended up with not just this, but anxiety (and) really bad panic attacks…. and she [BABS Clinician] started talking to me about everything then, and unravelling everything with me and straightening out everything that had happened. …I mean I’m in a lot better place now than what I was. (P29, recruited PN; 170 study days)

A key outcome for the study was to explore how reflective functioning (keeping the baby in mind) changed by participating in BABS and P25 reflected how BABS support enabled her to understand and respond to her baby’s needs:

I was diagnosed with postnatal depression, which then got changed to postnatal psychosis…. it took me a good two weeks before I got myself into learning what his cries were, what he needed at that time, how to soothe him when he wouldn’t settle…. looking back at it now, none of that was my fault. He was just being a baby, what I didn’t know is that they cry when they want affection, and I was under this lie that they only cry when they want feeding or they want changing, or when they’re tired….No, they cry when they feel lonely because they’re used to being inside you, and, all of a sudden, they’re in a basket…they just want some security. (P25, recruited PN; 89 study days)

The majority (85%) of mothers in our study experienced positive life enhancing changes because of their experience with BABS. Seven (15%) mothers (Participants: 1;2;3;5;12;14;21) recorded little difference in their total HADs score at TP1 and TP2. However, qualitatively, they expressed how positive the experience of the service had been. There was a similar finding for the P-PRFQ scores (Participants: 9;11;12) and MAAS-MPAS scores (Participants: 1;2;3,5;7;11;16;17) where positive comments aligned to a narrowed change in their scoring. When the cases were examined more closely qualitatively, a previous history of psychological disorder, lack of employment, a low level of education and involvement with social services were common denominators related to the HADS and MAAS-MPAS score. For those where there was less difference in P-PRFQ scores, qualitatively, no employment and low level of education was recorded.

Deeper qualitative analysis captured that some participants were not concerned with how they were bonding with their baby at recruitment. For example, Participant 11:

They …. referred me for advice about bonding with my baby… and [BABS clinician] said that the bonds with my babies are perfect, I don’t need [advice] to build any bonds with them. But I had other issues. I needed help to come to terms with the loss of my mum and dad so she referred me for that – bereavement counselling. (P11, recruited AN; 435 study days)

Participant 11 stayed in BABS care for the longest and was not depressed on admission. Therefore, a refinement in the inclusion criteria and referral process may facilitate enhanced targeting of the intervention based on a combination of maternal characteristics of pregnant mothers, who measure as depressed or anxious and who have a low level of reflective functioning and who demonstrate difficulty with attachment.

Strengths and limitations

This was a pragmatic study and there was no time defined period of admission to discharge as the intervention was provided based on patient need. Participants were English speaking and lived in a deprived area in England and it would be beneficial in future research for researchers to explore if the model of care is acceptable to mothers from diverse ethnic backgrounds in national and international settings. We used a mixed methods design which helped to capture complexity in maternal-infant attachment. However, there is a need to investigate if the beneficial changes captured in this study, relay to the infant of the dyad over a longitudinal period. It would be important for future research to include partners or copartners to capture non-gendered perspectives. There were no previous data to base a power calculation for this client group, which this study helps to provide. The small sample size undermines the potential to generalize findings and it would be important to design a larger study.

Discussion

In this study we explored how BABS intervention, in one setting in the UK, impacted upon maternal anxiety, depression and reflective functioning between admission and discharge. Mixed methods revealed complexity when investigating maternal attachment from a pragmatic stance (Tillman et al., Citation2011). On average mothers in our study significantly increased their ability to attach to their baby after the intervention was experienced, but for some, the score did not reflect the comments made. MAAS and MPAS have good reliability scores. However, a consensus statement recognizes ambiguity related to measuring attachment, stating that caregiver behavior should be at the center of decisions made about quality of attachment and they comment that it is important to question attribution of measures that inform important outcomes for families (Forslund et al., Citation2022) such as children being removed from mothers and placed into care. Furthermore, measuring attachment in ethnically diverse populations demands more sensitive tools to be validated as Çinar and Öztürk (Citation2014) and Keller (Citation2018) recognized that attachment styles may differ. Insensitive approaches used to determine the quality of maternal attachment, generate fear. The barrier is based on maternal fear of losing their babies and they comment that this emerges when they declare any type of vulnerability. Researchers reveal that vulnerability stems from judgemental professional behavior (Baskerville & Douglas, Citation2010; Briscoe et al., Citation2016; McCarthy & McMahon, Citation2008; Syvertsen et al., Citation2021). Therefore, decisions about maternal attachment in practice needs to be underpinned by a culturally sensitive evidence base within future research.

Mothers in this study lived in the second highest deprived borough in England with the third highest rate of children living with an educational need. The area reflects a lack of ethnic diversity, low level of people in same sex partnerships, increased birth rate, where younger individuals tend to conceive and the conditions are reflective of many international settings in high income countries. Sociodemographic risk factors identified nationally (Harron et al., Citation2021) were visible in our study to reflect a diverse range of biopsychosocial characteristics where adverse childhood events (ACE) such as domestic violence or involvement with social services were apparent. To investigate the impact of ACE, Lorenc et al. (Citation2020) performed a systematic review of reviews that included ages 3–18 highlighting the negative impact of ACE. Lorenc’s work recognized significant gaps in generalizable evidence about effective intervention and this evidence excluded ages 0–2 years which is a timeline considered to be an important factor that was included in our study. Longitudinal outcomes of ACE for under twos were investigated in the US for 245 children and the data was based on recruitment between 1992 and 1994 (Melville, Citation2017). However, only 56% (n = 138) were followed up at age 18 between 2009 and 2001. Therefore, there is a need for more robust evidence from international settings related to effective culturally sensitive interventions that interrupt ACE and impact positively for mothers with children under two, and this BABS model of care may provide one solution.

Our study included an at-risk population and there are known issues with recruitment and retention in research with vulnerable at-risk populations (Bonevski et al., Citation2014). However, a very low decline or loss to follow up rate was evidenced in our study. Regardless of the difficulty in accessing deprived populations, it is of continued importance for clinical, academic and commissioning collaborations to use research to build complex interventions that reduce inequalities in society to support parents to attach positively with their offspring, especially during a pandemic (Institute of Health Equity (IHE), Citation2020). In the UK, 4.2 million children live in poverty (The Child Poverty Action Group, Citation2020), and globally, there is an expectation that 150 million people will live in poverty by the end of 2021, where half of the poor will be children (World Bank, Citation2021). The Children’s Commission (Citation2020) estimated that; 370,000 under-fives live with parents suffering with mental ill health, 144,000 live with parents suffering from drug or alcohol problems, and 235,000 live with domestic violence in the UK. It would be interesting to explore mother’s perceptions of bonding and attachment via a larger study, involving an international cohort, since restricted living conditions have been experienced globally.

Action is required by those who commission health globally to ensure that there are Parent Infant Mental Health Services (PIMHS) available to break a transgenerational cycle of negative attachment behavior. However, in the UK, parents do not have access to the specialist support they need (Hogg, Citation2013) where only 27 specialist PIMHS exist and most babies in the UK live in an area where there is no Parent Infant Mental Health Services at all (Hogg, Citation2019). A potential reason for a lack of accessible PIMHS may be due to underfunded research around this topic (DH, Citation2017) which is now called for as a priority in the UK (NIHR, Citation2020).

Prevention is a priority for research, practice and educational goals. Even though this was a small study, BABS intervention made a statistically and clinically significant positive difference to the lives of mothers. For example, two mothers who contemplated suicide had their thoughts interrupted by participating in this study (P25;P29). The devastation incurred because of maternal suicide cannot be underestimated. In the UK, maternal suicide has been classified as the leading cause of direct deaths incurred within the first year after birth and there was no significant change in the rate between 2009 and 2018 (Knight et al., Citation2020). Globally, there are discrepancies in how maternal suicide data is collected and the phenomenon is embedded into coincidental, direct or an indirect categories. Variation makes the global figure difficult to calculate (Say et al., Citation2014) and an international standardized system of reporting maternal suicide is called for. In Knight et al. (2020)’s report, out of 217 mothers who died over the three-year period (2016–2018), eight (17%) deaths were attributed to suicide. It is a stark reminder that in our study, which involved only 46 mothers over a shorter period, two of the mothers had contemplated suicide. Crucially, it is important to recognize that the preventative intervention created by the BABS service has supported at least two participants to stay alive and remain mothers and who commented that they were better able to attach with their infants after involvement with BABS.

Preventative outcomes need to be aligned to cost effective care. Howard and Khalifeh (Citation2020) performed a robust systematic review of 49 studies and determined that there is no definitive evidence to explain the cost effectiveness of psychological or psychosocial interventions related to maternal mental health interventions. However, there is a cost burden of £75,728.00 (related to depression) and £34,840.00 (related to anxiety) that is spent in the UK per individual in her lifetime and the aggregated cost for the country is £6.6 billion. Consequently, 75% of this economic burden is associated with subsequent childhood morbidity (Bauer et al., Citation2016). The cost to the public sector of maternal mental ill health is five times greater than the cost of providing the preventative services that are needed throughout the UK (Maternal Mental Health Alliance, Citation2014). It is important to understand that without prevention or generalizable, culturally sensitive, cost effective early intervention strategies, reduced levels of bonding and attachment can become transgenerational and involve sustained long-term impacts on society. Ambiguities in literature reflect an urgent need to calculate which parent/infant interventions work best to support positive attachment globally.

Conclusion

It is crucial that clinicians, researchers, commissioners and policy makers internationally, recognize ambiguity or lack of definition around concepts used to classify complex maternal/parent-fetal/infant attachment behavior in order to guide appropriate critical clinical decisions about supporting at risk mothers during their maternal journey. Refinement of the referral process to BABS needs to be explored within future new research. However, it was clear that BABS filled a gap in service provision in the UK that helped to educate and support mothers and facilitated positive, lifesaving, clinical outcomes. Therefore, Parent Infant Mental Health Services, based on a midwifery/psychologist model of care, targeted at supporting at risk families between the antenatal-postnatal continuum needs to underpin future research.

CRediT author statement

Lesley Briscoe: Conceptualization, methodology, validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing original and drafts, visualization, supervision, project administration, funding acquisition. Lisa Marsland: Conceptualization, clinical care provision, methodology, reviewing. Carmel Doyle: Clinical care provision, reviewing. Gemma Docherty: Independent provision of questionnaires to research team, review. Anita Flynn: Formal analysis, review. Phillip Gichuru: Validation, formal analysis, investigation, data curation, writing drafts and original, visualization.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was gained from The NHS Research Authority (Reference: IRAS 241481) and The Faculty of Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee (Reference: CYPF 9).

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank: the participants; The Pride Children’s Centre, Knowsley, UK; Allison Wright (Specialist Midwife), Jessica May, and Dr Victoria Appleton, PhD (Research Assistants) for their contribution to this study.

Data sharing statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [LB], upon reasonable request.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this article.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

Dr. Lisa Marsland and Carmel Doyle ran the clinical care for the BABS service. However, they were not part of the research team. Questionnaire data was handed over by an administrator. Data collection, management, and analysis were carried out in Edge Hill University, independently of the care team.

There are no financial, personal, or competing interests that influenced the work reported in this article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Altman, D. G. (1991). Practical statistics for medical research. Chapman and Hall, CRC.

- Barlow, J., Bennett, C., Midgley, N., Larkin, S. K., & Wei, Y. (2015). Parent-infant psychotherapy for improving parental and infant mental health. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD010534. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD010534.pub2

- Barlow, J., Bennett, C., Midgley, N., Larkin, S. K., & Wei, Y. (2016). Parent–infant psychotherapy: A systematic review of the evidence for improving parental and infant mental health. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 34(5), 464–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646838.2016.1222357

- Baskerville, T. A., & Douglas, A. J. (2010). Dopamine and oxytocin interactions underlying behaviors: Potential contributions to behavioral disorders. CNS Neuroscience & Therapeutics, 16(3), e92–e123. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-5949.2010.00154.x

- Bauer, A., Knapp, M., & Parsonage, M. (2016). Lifetime costs of perinatal anxiety and depression. Journal of Affective Disorders, 192(March), 83–90.

- Bonevski, B., Randell, M., Paul, C., Chapman, K., Twyman, L., Bryant, J., Brozek, J., & Hughes, C. (2014). Reaching the hard-to-reach: A systematic review of strategies for improving health and medical research with socially disadvantaged groups. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 14(March), 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-14-42

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Vol 1: Attachment (Pimlico edition 1997). Hogarth Press and The Institute of Psychoanalysis. Random House.

- Bowlby, J. (1998). Attachment and loss. Vol 111, Loss sadness and depression (Pimlico edition 1998). Random House.

- Bowlby, J., Fry, M., & Salter Ainsworth, M. D. (1965). Child care and the growth of love (2nd ed.), (Part III) Penguin Books.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Briscoe, L., Lavender, T., & McGowan, L. (2016). A concept analysis of women’s vulnerability during pregnancy, birth and the postnatal period. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(10), 2330–2345. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.13017. Epub 2016 Jun 3.

- Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. (2016). Handbook of attachment, theory, research and clinical applications (3rd ed.). The Guildford Press.

- Cassidy, J., Jones, J. D., & Shaver, P. R. (2013). Contributions of attachment theory and research: A framework for future research, translation, and policy. Development and Psychopathology, 25(4 Pt 2), 1415–1434. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000692

- Çinar, I. O., & Öztürk, A. (2014). The effect of planned baby care education given to primiparous mothers on maternal attachment and self-confidence levels. Health Care for Women International, 35(3), 320–333. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2013.842240

- Condon, J. (1993). The assessment of antenatal emotional attachment: Development of a questionnaire instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 66(2), 167–183. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1993.tb01739.x

- Condon, J., & Corkindale, C. (1997). The correlates of antenatal attachment in pregnant women. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 70(4), 359–372. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1997.tb01912.x

- Condon, J., & Corkindale, C. (1998). The assessment of parent-to-infant attachment: Development of a self-report questionnaire instrument. Journal of Reproductive and Infant Psychology, 16(1), 57–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/02646839808404558

- Cooper, H., Lancaster, G. A., Gichuru, P., & Peak, M. (2018). A mixed methods study to evaluate the feasibility of using the Adolescent Diabetes Needs Assessment Tool App in paediatric diabetes care in preparation for a longitudinal cohort study. Pilot and Feasibility Studies, 4, 13. 10.1186/s40814-017-0164-5

- Crawford, J. R., Henry, J. D., Crombie, C., & Taylor, E. P. (2001). Brief report normative data for the HADS from a large non-clinical sample. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 40(4), 429–434. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466501163904

- Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2018). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods approaches (5th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Creswell, J. W., & Plano Clark, V. L. (2018). Designing and conducting mixed methods research (3rd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans- Kranenburg, M. J., & van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990289

- DH. (2017). Framework for mental health research. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/665576/A_framework_for_mental_health_research.pdf

- Duschinsky, R., & Solomon, J. (2017). Infant disorganized attachment: Clarifying levels of analysis. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 22(4), 524–538.

- EQUATOR Network. (2021). Enhancing the quality and transparency of health research. https://www.equator-network.org/

- Evertz, K., Janus, L., & Linde, R. (Eds.) (2020). Handbook of prenatal and perinatal psychology. Integrating research and practice. Springer International Publishing AG, ProQuest Ebook Central. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/edgehill/detail.action?docID=6380931.

- Fetters, M. D., & Molina-Azorin, J. F. A. (2019). Checklist of mixed methods elements in a submission for advancing the methodology of mixed methods research. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 13(4), 414–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689819875832

- Forslund, T., Granqvist, P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Sagi-Schwartz, A., Glaser, D., Steele, M., Hammarlund, M., Schuengel, C., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., Steele, H., Shaver, P. R., Lux, U., Simmonds, J., Jacobvitz, D., Groh, A. M., Bernard, K., Cyr, C., Hazen, N. L., Foster, S., … Duschinsky, R. (2022). Attachment goes to court: Child protection and custody issues. Attachment & Human Development, 24(1), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2020.1840762

- Fraiberg, S., Adelson, E., & Shapiro, V. (1975). Ghosts in the nursery: A psychoanalytic approach to the problems of impaired infant-mother relationships. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry, 14(3), 387–421. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0002-7138(09)61442-4

- Goulden, C. H. (1956). Chapter V1 linear regression methods of statistical analysis (2nd ed., pp. 52–64). Wiley.

- Harron, K., Gilbert, R., Fagg, J., Guttmann, A., & van der Meulen, J. (2021). Associations between pre-pregnancy psychosocial risk factors and infant outcomes: A population-based cohort study in England. The Lancet, 6(2), e97–e105. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30210-3

- Harwood, R. L., Schoelmerich, A., & Schulze, P. A. (2000). Homogeneity and heterogeneity in cultural belief systems. In S. Harkness, C. Raeff & C. M. Super (Eds.), Variability in the social construction of the child (Vol. 87, pp. 41–57). Jossey-Bass.

- Herrmann, C. (1997). International experiences with the hospital anxiety and depression scale: A review of validation data and clinical results. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 42(1), 17–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-3999(96)00216-4

- Hogg, S. (2013). Prevention in mind: All babies count: Spotlight on perinatal mental health. NSPCC Report. https://www.nspcc.org.uk/globalassets/documents/research-reports/all-babies-count-spotlight-perinatal-mental-health.pdf

- Hogg, S. (2019). Rare Jewels: Specialised parent-infant relationship teams in the UK. PIP UK. https://parentinfantfoundation.org.uk/our-work/campaigning/rare-jewels/

- Holmes, P., & Farnfield, S. (Eds.) (2014). The Routledge handbook of attachment: Implications and interventions. Routledge.

- Howard, L. M., & Khalifeh, H. (2020). Perinatal mental health: A review of progress and challenges. World Psychiatry, 19(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20769

- Huang, R., Yang, D., Lei, B., Yan, C., Tian, Y., Huang, X., & Lei, J. (2020). The short-and long-term effectiveness of mother–infant psychotherapy on postpartum depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 260, 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.09.056

- Institute of Health Equity (IHE). (2020). Build Back Fairer: The COVID-19 Marmot review: The pandemic, socioeconomic and health inequalities in England. http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/build-backfairer-the-covid

- Keller, H. (2018). Universality claim of attachment theory: Children’s socioemotional development across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(45), 11414–11419. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1720325115

- Knight, M., Bunch, K., Tuffnell, D., Shakespeare, J., Kotnis, R., Kenyon, S., & Kurinczuk, J. J. (Eds.) (2020). MBRRACE-UK. Saving lives, improving mothers’ care – Lessons learned to inform maternity care from the UK and Ireland Confidential Enquiries into Maternal Deaths and Morbidity 2016-18. National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit, University of Oxford. https://www.npeu.ox.ac.uk

- Leadsom, A., Field, F., Burstow, P., & Lucas, C. (2014). The 1001 critical days the importance of the conception to age two period. A cross-party Manifesto. http://www.wavetrust.org/

- Lorenc, T., Lester, S., Sutcliffe, K., Stansfield, C., & Thomas, J. (2020). Interventions to support people exposed to adverse childhood experiences: Systematic review of systematic reviews. BMC Public Health, 20(1), 657. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-020-08789-0[PMC][32397975

- Maternal Mental Health Alliance. (2014). Counting the costs. https://maternalmentalhealthalliance.org/campaign/counting-the-costs/

- McCarthy, M., & McMahon, C. (2008). Acceptance and experience of treatment for postnatal depression in a community mental health setting. Health Care for Women International, 29(6), 618–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330802089172.

- Melville, A. (2017). Adverse childhood experiences from ages 0–2 and young adult health: Implications for preventive screening and early intervention. Journal of Child & Adolescent Trauma, 10(3), 207–215. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40653-017-0161-0

- Muzik, M., London-Bocknek, E., Broderick, A., Richardson, P., Rosenblum, K. L., Thelen, K., & Seng, J. S. (2013). Mother-infant bonding impairment across the first six months postpartum: The primacy of psychopathology in women with childhood abuse and neglect histories. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 16(1), 29–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0312-0

- Mykletun, A., Stordal, E., & Dahl, A. A. (2001). Hospital Anxiety and Depression (HAD) scale: Factor structure, item analyses and internal consistency in a large population. British Journal of Psychiatry, 179(6), 540–544. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.179.6.540

- NICE. (2010). Pregnancy and complex social factors: A model for service provision for pregnant women with complex social factors. Retrieved, 2021 August 7, from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg110

- NICE. (2021). Antenatal care guideline. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng201

- NIHR. (2020). Mental Health Research Goals 2020-2030. https://acmedsci.ac.uk/file-download/63608018

- Nowell, L. S., Norris, J. M., White, D. E., & Moules, N. J. (2017). Thematic analysis: Striving to meet the trustworthiness criteria. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 16(1), 160940691773384–160940691773313. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406917733847

- O’Caithain, A., Murphy, E., & Nicholl, J. (2010). Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. British Medical Journal, 17(341), 1147–1150. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c4587

- Pajulo, M., Tolvanen, M., Karlsson, L., Halme-Chowdhury, E., Öst, C., Luyten, P., Mayes, L., & Karlsson, H. (2015). The Prenatal Parental Reflective Functioning Questionnaire: Exploring factor structure and construct validity of a new measure in The Finn Brain Birth Cohort Pilot Study. Infant Mental Health Journal, 36(4), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21523. PMID: 26096692.

- Ritchie, J., & Spencer, L. (1994). Chapter 9: Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In Bryman, A., & Burgess, R. G. (Eds.), Analysing qualitative data (pp. 173–194). Routledge.

- Say, L., Chou, D., Gemmill, A., Tunçalp, O., Moller, A. B., Daniels, J., Metin Gülmezoglu, A., Temmerman, M., & Alkema, L. (2014). Global causes of maternal death: A WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet. Global Health, 2(6), e323–e333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(14)70227-X

- Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906

- Spencer, L., Ritchie, J., & O’Connor, W. (2003). Chapter 8: Analysis: Practice, principles and processes. In Ritchie, J., & Lewis, J. (Eds.), Qualitative research practice: A guide for social science students and researchers (pp. 199–218). Sage Publications.

- Srivastava, A., & Thompson, S. B. (2009). Framework analysis: A qualitative methodology for applied policy research. Journal of Administration and Governance, 4(2), 72–79.

- Syvertsen, J. L., Toneff, H., Howard, H., Spadola, C., Madden, D., & Clapp, J. (2021). Conceptualizing stigma in contexts of pregnancy and opioid misuse: A qualitative study with women and healthcare providers in Ohio. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 222, 108677–108676. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.108677

- The Child Poverty Action Group. (2020). Child poverty facts and figures. https://cpag.org.uk/child-poverty/child-poverty-facts-and-figures

- The Children’s Commission. (2020). Childhood in the Time of COVID. https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/cco-childhood-in-the-time-of-covid.pdf

- Tillman, J. G., Clemence, A. J., & Stevens, J. L. (2011). Mixed methods research design for pragmatic psychoanalytic studies. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 59(5), 1023–1040. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003065111418650

- Verbeke, G., & Molenberghs, G. (2000). Linear mixed models for longitudinal data. Springer series in statistics.

- World Bank. (2021). Poverty. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/poverty/overview

- World Health Organisation. (2006). preventing child maltreatment: A guide to taking action and generating evidence. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43499

- Zigmond, A. S., & Snaith, R. P. (1983). The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 67(6), 361–370. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x