?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

This study presents an initial effort to develop disordered eating pathology (DEP) prevention program with an emphasis on maternal involvement. Disordered eating pathology representing a range of behaviors and attitudes, from negative body image to full-blown eating disorder. It appears mainly in adolescent females and related to psychological and familial factors, including maternal modeling of thinness. A sample of 118 Israeli girls (11–12) was divided into three groups: participants in the program in parallel with their mothers, participants without their mothers, and control. Participants completed self-report questionnaires. Groups were tested three times: pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up. For those girls who participated in parallel with their mothers, higher self-esteem was associated with fewer pathological diet behaviors. Findings deepen understanding of the risk factors involved in the development of DEP. The main study contribution is the important role mothers play in preventing DEP among their daughters.

Eating disorders are a complex, worldwide problem that affects mostly girls and women (Keski-Rahkonen et al., Citation2018). To date, only a few interventions have been found to be effective in the long term (Hart et al., Citation2015). In this article, we evaluate the efficacy of an intervention program for adolescent girls and their mothers and compare it with a similar program for adolescent girls without their mothers and with a control group. We compared three groups of participants: (a) girls with their mothers, (b) girls without their mothers, and (c) a control group of girls without any intervention. Our main contribution is for health and youth professionals worldwide, and our intent is to contribute to the theoretical and practice global literature regarding eating disorders prevention among girls and women.

Disordered eating pathologies and eating disorders

Problems related to food and body fall along a spectrum, ranging from body image disorders to the development of full-blown eating disorders (EDs) (Hoek, Citation2016; Smink et al., Citation2012). Disordered eating pathology (DEP) includes thoughts and behaviors such as a preoccupation with weight, body, and food. It is primarily manifested in calorie restriction, constant dieting, excessive exercise routines, binge-purge behavior, and the use of laxatives and diuretics to control weight (Latzer et al., Citation2015). These behaviors constitute a significant risk factor for the development of clinical EDs, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa (Zipfel et al., Citation2015).

In recent decades, there has been a consistent rise in the prevalence of DEPs and EDs in North America, Europe, and the Middle East, including Iran, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), Lebanon, and Israel (Latzer et al., Citation2008; Schmidt et al., Citation2016; Smink et al., Citation2012). The estimated worldwide prevalence of DEPs and EDs increased from 3.5% between 2003-2006 to 7.8% between 2013-2018 (Galmiche et al., Citation2019), and a similar such increase was found in Israel (Latzer et al., Citation2008; Smink et al., Citation2012). Adolescents in Israel have unique ED and DEP characteristics. In addition to their exposure to media and socio-cultural values that encourage thinness, Israelis experience high levels of stress because of the many internal and external conflicts that take place in the area. Stress is a significant risk factor for developing eating pathologies and a significant predictor of a high level of EDs (Latzer et al., Citation2008). In Israel, approximately one-fifth of all adolescents display disordered eating symptoms, with the highest rate being found among girls ages 16-18 (Greenberg et al., Citation2007; Latzer et al., Citation2015).

In the past, the prevalence of EDs was assumed to be lower in Middle Eastern countries than in the USA and Europe. Today, ED prevalence in the Middle East is rising rapidly and is considered to be even higher in this area than in the USA (Kronfol et al., Citation2018). In the last two decades, there have been rapid sociocultural changes in Middle Eastern countries that reinforce the ideal of thinness among women (Melisse et al., Citation2020). In addition, major financial and political changes have taken place in the Middle East, known for its high levels of conflict and lack of resources for contending with them (Kronfol et al., Citation2018). Researchers have recently indicated that 13-55% of the population is at high risk for EDs, and that the prevalence among girls and women is higher than among boys and men (Melisse et al., Citation2020). In Iran, for example, 24.2% of boys and girls ages 13-18 scored above the clinical cutoff on the EAT-26 questionnaire (Rauof et al., Citation2015). Researchers who conducted a study in the UAE found that 29.0% of female university students scored above the clinical cutoff on the EAT-26 (Thomas et al., Citation2018). In Lebanon, 21% of female university students were diagnosed with an ED (Doumit et al., Citation2017).

The onset of eating-related problems typically occurs in early adolescence, and adolescent girls are considered a prime target population for research and prevention efforts (Micali et al., Citation2017; Stice et al., Citation2019). Researchers have shown that 50% of adolescent girls have a DEP, and that rates are increasing (Neumark-Sztainer et al., Citation2011; Sanlier et al., Citation2017). These alarming rates, in various countries, attest to the need to identify risk and protective factors in this high-risk group.

Risk factors for DEPs and EDs

The underlying causes of DEPs, and ultimately EDs, involve a complex interplay between genetic, biological, psychological, family-related, and sociocultural factors (Hilbert et al., Citation2014; Levine & Smolak, Citation2009; Stice et al., Citation2011). An important role is played by normative challenges associated with early adolescence, such as physical changes, increased desire for peer acceptance, social comparison, and low self-esteem (Gardner & Steinberg, Citation2005; Tetzner et al., Citation2017).

Psychological risk factors: Self-esteem and body image

Low self-esteem is considered to be a prime psychological risk factor (Murnen & Smolak, Citation2019). Self-esteem has been defined as one’s attitude toward the self (Cella et al., Citation2020), and researchers have shown that it affects one’s quality of life and health (Wu et al., Citation2016). For example, low self-esteem has been found to be associated with EDs, whereas high self-esteem plays an important role in the prevention of DEPs and body dissatisfaction (Sanlier et al., Citation2017). One of the major components of self-esteem is body image.

Body image, defined as one’s perceptions, thoughts, feelings, and actions taken toward one’s body (Thompson & Schaefer, Citation2019), is one component of a global self-esteem construct (Grogan, Citation2021). A negative body image is considered to be a psychological risk factor (Murnen & Smolak, Citation2019) and is a critical factor in the development of EDs in adolescents (Stice et al., Citation2019). A healthy body image is typically accurate and positive; an unhealthy one is typically inaccurate and negative (Tiggemann, Citation2015).

Low self-esteem and body dissatisfaction have been found to promote unhealthy dieting behaviors (Stice et al., Citation2011). In turn, dieting, defined as the intentional and consistent restriction of caloric intake for weight management purposes, promotes eating disturbances (Schaumberg et al., Citation2016). Unhealthy dieting behaviors are also considered to be influenced by the family (Balantekin, Citation2019).

Family risk factors: Maternal modeling

Mothers have historically been blamed for the onset of EDs of their daughters (Rabinor, Citation1996; Vander Ven & Vander Ven, Citation2003). But ED professionals have been moving away from blaming mothers and toward paying greater attention to how to best use mothers in the treatment of their daughters to increase the likelihood of their daughters’ recovery (Lock & Le Grange, Citation2005). Although blaming is no longer acceptable in the treatment of EDs, some family-related risk factors have still been found to be associated with EDs (Le Grange et al., Citation2010). One such factor, in both DEP and EDs, is maternal modeling of weight, body shape, and eating behaviors. Parents, in particular mothers, play a critical role in how their children, especially daughters, think and feel about their bodies, food, and weight (Brun et al., Citation2021; Cooper & Stein, Citation2013). Mothers serve as important role models (Handford et al., Citation2018) for their children, especially for their daughters, in matters of eating behaviors (Martini et al., Citation2019). Mothers pass on ideas about eating and physical appearance through their own diet and exercise patterns (Ragelienė & Grønhøj, Citation2020), more so than fathers do. Although fathers greatly affect their children’s well-being and development (Lamb & Lewis, Citation2013), mothers are still considered to be more involved in the feeding of their children (Panter-Brick et al. Citation2014).

Researchers have shown that maternal eating behaviors (dieting, restraint, and disinhibition) increase a child’s risk of body image issues and DEPs (Cutting et al., Citation1999; Hart et al., Citation2015). Similarly, researchers have shown that mothers’ modeling of thinness is associated with their daughters’ bulimic symptoms (Hillard et al., Citation2016). Mothers’ behavior, therefore, significantly affects their daughters, and both mothers and daughters, worldwide, are influenced by the societal and cultural atmosphere around them. According to the socio-cultural model (Stice et al., Citation1994), both mothers and daughters are subject to many environmental and cultural influences, such as exposure to thin-idealized bodies and social media messages that contribute to low body image and low self-esteem, which increase the risk of EDs and DEPs (Brun et al., Citation2021; Mills et al., Citation2017).

Societal and cultural risk factors

Societal and cultural values are an additional risk factor for the development of EDs, especially values that equate thinness with beauty, popularity, happiness, and success (McLean et al., Citation2017). In the last four decades, the media has played an important role in the development of EDs by exposing users to messages about desirable and undesirable body features (McLean et al., Citation2017). Such messages can lead to social pressure to achieve thinness, especially in young women (Weissman, Citation2019). Exposure to harmful media messages consisting of photos, many of them retouched, photoshopped, and processed through filters, occurs primarily through social media networks (Guest, Citation2016). Researchers have found that women and young girls who use social networks have lower body image and higher DEP and ED levels than do those who do not use social networks (Hinojo-Lucena et al., Citation2019; Sadeh-Sharvit et al., Citation2020). Researchers have also regarded these pathological attitudes and behaviors, the origins of which are believed to be societal and cultural, as psychological problems experienced in particular by women (Moulding & Hepworth, Citation2001).

Our research is based on the social comparison theory (Festinger, Citation1954), according to which, human beings have an innate drive to compare themselves to others like them in order to understand how and where they fit into the world. This comparison includes appearance-related aspects. Comparisons of appearance are common for women globally, and mothers, like their daughters, tend to compare themselves to unrealistic images presented in the media and to have impractical expectations of themselves or of their daughters (Moy, Citation2015). Such comparisons may lead to harmful negative outcomes, including body dissatisfaction and DEPs (Fitzsimmons-Craft, Citation2011). Such outcomes are the result of the discrepancy between a woman’s real body and the ideal one she would like or expects to have (Fitzsimmons-Craft et al., Citation2016). Practitioners who run ED prevention programs that aim to reduce the negative effect of such comparisons focus on media literacy and dissonance-based interventions (Rohde et al., Citation2015). The methodological content of the prevention program in the current study was based on the social comparison theory and the identification of multiple combined risk factors for EDs: psychological, family-related, societal, and cultural.

Eating disorder prevention programs

Researchers conducting ED prevention research have mapped ED risk factors to produce tailored interventions based on these multiple combined risk factors (Cheng et al., Citation2019; Stice & Desjardins, Citation2018). In recent studies, preventive interventions have been found to produce significant effects on ED risk factors, but there has been limited success in replicating these changes over time (Dakanalis et al., Citation2019; Stice et al., Citation2013). ED prevention programs aimed at strengthening self-esteem have been found to be effective in reducing DEPs in adolescent girls (Levine, Citation2019). One of the main recommendations of experts in the prevention of girls’ EDs is to involve significant others, such as parents, particularly mothers, in intervention programs (Hart et al., Citation2015) to achieve long-term behavioral changes (Stice et al., Citation2019). Mothers play an important role in the example they set for their daughters in relation to food, eating, and weight (Snoek et al., Citation2009), and have the potential to promote healthy discourse about body image and self-esteem (Maor & Cwikel, Citation2016). But many existing programs have included both parents (i.e., mothers and fathers) and researchers have failed to recruit sufficient sample sizes to enable significant statistical analyses (Hart et al., Citation2015). Although the importance of involving parents in ED prevention programs has been established (Berger et al., Citation2011), it has been difficult and almost impossible (on a practical level) to involve them in face-to-face interventions because the sessions usually take place in the evening, when participants find it difficult to arrive (Corning et al., Citation2010; Fiissel, Citation2005). To the best of our knowledge, there has been only one tailored intervention program for mothers in this area. Corning and colleagues (Citation2010) examined the efficacy of the “Healthy Girls Project,” a prevention program aimed by the professionals to reduce body image problems in middle-school girls via an intervention that took place directly and only with their mothers. The intervention for the mothers comprised a series of four weekly workshops that included interactive psychoeducational and behavioral components. Daughters did not participate in the intervention, but they completed questionnaires at three time points: before the intervention, after the intervention, and at a three-month follow-up. The researchers found that at both post-intervention and follow-up, girls whose mothers were in the intervention group perceived less pressure from their mothers to be thin than did girls whose mothers did not participate. At follow-up, these girls also showed a lower drive for thinness.

We are not aware of any professionals in the field of ED prevention program that has included mothers and daughters in parallel—that is, where mothers and daughters participate but not together (i.e., with each being in a different group, and the group meetings taking place at different times). In the present study, our purpose was to evaluate an ED prevention program that included both mothers and their daughters, as described below, and in so doing contribute to the theoretical and practice global literature of how mothers influence their daughters in relation to eating behaviors and self-esteem.

The program and its evaluation

The aim of the developers of the ED prevention program “Full of Ourselves” was to promote self-esteem, positive body image, and leadership in girls (Sjostrom & Steiner-Adair, Citation2005), so as to prevent or reduce DEPs and EDs. The idea for the program was based on the recommendation that interventions focusing on the family as a contributing risk factor for EDs may reduce harmful attitudes and behaviors (Keski-Rahkonen & Mustelin, Citation2016; Lock & Le Grange, Citation2019) and empower the family, which also has the potential to reduce ED symptoms (Lock & Le Grange, Citation2019).

We evaluated the program based on three groups of young adolescent girls (ages 11-12): Group 1 participated in the prevention program with their mothers (treated in parallel groups); Group 2 participated in the program without their mothers; Group 3 was not exposed to the intervention program, and neither were the mothers (control group).

The adolescents’ intervention

The intervention program was based on Sjostrom & Steiner-Adair’s (Citation2005) “Full of Ourselves” program mentioned above. The aim of the program leaders was to reduce the likelihood of adolescent girls engaging in DEP behaviors by promoting self-esteem, positive body image, and leadership. The program leader also taught participants to use coping strategies designed to counteract the cultural effects of preoccupations with body image and unhealthy eating and dieting behaviors. The intervention protocol was based on the original program and adapted to the local population by the PI and by Dr. Steiner-Adair, the author of “Full of Ourselves.” Meetings were held once a week on school days, for an hour, over a four-month period. They were led by the first author, the PI, a social worker specializing in working with adolescent girls.

The mothers’ intervention

The mothers of girls in Group 1 participated in four sessions: three psycho-educational group meetings and an individual meeting. The psycho-educational meetings were based on a protocol that provided mothers with guidance, knowledge, and support. In the first meeting, the focus was on distinguishing between the ideal of thinness and health; in the second meeting, the focus was on mothers’ handling of communication and discourse with their daughters about the unrealistic ideal of thinness; in the third meeting, the focus was on alternatives to pervasive societal discourse, so that mothers could help their daughters form a positive body image, recognize harmful media messages and ways to reduce their influence on their daughters, and recognize EDs and their warning signs. In the individual meetings, the focus was on the particular content raised by each mother on these subjects. The PI asked mothers direct questions such as, “What was most significant for you during the process? Did you apply anything learned in the meetings with your daughter? What was hard for you to apply? Did your daughter talk to you about the activities in which she participated? Do you think that your husband/spouse should also be part of the program? Is there anything else that you would have liked to learn, and you didn’t?”

Our research hypotheses are described below.

Hypotheses

Our overall research hypothesis was that significantly fewer dieting behaviors would be found in girls who participated in parallel ED prevention interventions with their mothers than among (a) girls who participated in the program without their mothers and (b) girls who were not exposed to the program (control group). We expected that:

Maternal modeling of thinness would be associated with lower self-esteem and more dieting behaviors of the daughters.

Higher self-esteem would be associated with fewer dieting behaviors.

Girls whose mothers participated in the intervention program would show a greater increase in self-esteem and a greater decrease in dieting behaviors over time (pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at follow-up) than would girls who participated in the intervention program without their mothers and girls in the control group.

Self-esteem would mediate the association between maternal modeling of thinness and dieting behaviors, so that less modeling would be linked with higher self-esteem and fewer dieting behaviors in the daughters. The intervention with mothers would moderate this mediation by increasing self-esteem and the effect of self-esteem on dieting behaviors.

Method

Sample

Initially, 140 sixth-grade Jewish girls were recruited from secular elementary schools in Israel. A convenience sample was used (all girls in the classroom). Of these, 22 girls (15.7%) either refused to participate (because they or their parents objected) or failed to complete the questionnaires. The final sample consisted of 118 adolescent girls, ages 11-12 (M = 11.5; SD = 0.5), and the mothers of 35 of these girls. Most of the girls (81%) were from a small rural community in northern Israel, and the rest were from a small city, in the same general area on Israel’s periphery. Participants were divided into three groups: two intervention groups and a control group. Seventy girls were included in the intervention groups: 35 who participated with their mothers (in parallel but separate groups) and 35 who participated without their mothers. The remaining 48 girls were in the control group. All participants were native speakers of Hebrew.

shows the participants’ frequencies and percentages of demographic variables. We found no significant differences in any of the demographic variables among the girls participating in the study: economic status ((3) = 3.5, p > 0.5), maternal education (

(3) = 5.6, p > 0.5), and paternal education (

(3) = 2.2, p > 0.5). We also found no significant differences in the girls’ personal variables (age, weight, and height). The participants’ mean body mass index (BMI)Footnote1 was 18.5 (SD ± 3.4). All of the study participants were from the same geographical area, where there is a great degree of homogeneity in the population’s characteristics (thus accounting for the similarity of the participants’ demographic variables). Also, the study was conducted among a sample of adolescent girls in the same age group, and it is likely that this is the reason why no differences were found in their personal background variables.

Table 1. Means, standard deviations, and percentages of physical and demographic variables in all study groups (N = 118).

Participants self-reported their weight and height data. On average, the girls in the study had an age-appropriate weight range; that is, they were considered a healthy population.

Measures

The girls completed a background questionnaire at the beginning of the study. It included demographic questions and questions about weight and height (1).

We conducted the study over a period of almost a year and a half, during which time we evaluated participants at three time points to examine the relative effectiveness of the intervention: the pretreatment baseline time point (T1); the post-intervention time point, (T2); and the follow-up, 6-8 months after the end of the intervention, (T3). We administered the three intervention questionnaires (see below) to the girls at time points T1, T2, and T3. We used these indicators for the same content measures at all three time points.

We assessed dieting behavior by two self-report measures: the Dutch Restrained Eating Scale (DRES; van Strien et al., Citation1986) and the Dietary Intent Scale (DIS; Stice et al., Citation1998), translated into Hebrew. The two scales were strongly correlated (r = .92); therefore, we combined them into one measure, and retained all items. Participants indicated the extent to which they engaged in each of the 10 behaviors described on a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (5). Scores were summed, with higher scores indicating a more frequent occurrence of dieting behaviors. A sample item was: “If you feel you have gained weight, do you reduce the amount of food you normally eat?” Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .90, .84, and .90 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

We measured self-esteem using the 10-item self-report Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (Rosenberg, Citation1965), translated into Hebrew. Participants rated each item on a 4-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 10 (high self-esteem) to 40 (low self-esteem). Five items were phrased negatively (e.g., “At times I think I am no good at all”) and reverse-scored. Internal reliability has been shown to range from .80 to .85 (Rosenberg, Citation1965). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .88, .90, and .93 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

We assessed maternal modeling of thinness with the 4-item self-report Modeling of Eating Disturbances questionnaire, a subscale of the Bulimic Modeling Scale (Stice, Citation1998), translated into Hebrew. The measure refers to such DEP behaviors as binge eating, compensatory behaviors, and preoccupation with weight (sample item: “One or more of my family members has dieted to lose weight”). Participants responded along a 5-point Likert scale, never (1) to often (5), with total scores ranging from 4 to 20. In the present study, we changed the wording to reflect maternal modeling, so that instead of a general question about the family, the question explicitly mentioned mothers (e.g., “My mother has dieted to lose weight”). We omitted one question from the original scale (“One of my family members vomits to lose weight”) because the Chief Scientist of the Israel Ministry of Education did not approve it. Previously reported reliability was .88 (Stice, Citation1998). Cronbach’s alpha in the present study was .77, .72, and .77 for T1, T2, and T3, respectively.

Procedure

The study was approved by the Chief Scientist of the Israel Ministry of Education. We informed all parents about the intervention program and asked them to have their daughters notify the school in the event that the parents did not consent to the children’s participation in the research. The PI conducted the intervention program in school during the school year; questionnaires were administered by the first author and completed during school hours. It took approximately 45 minutes to complete the questionnaires, and the girls were told they could stop whenever they wished, without repercussions for having discontinued their participation. Contact information with an emergency phone number was provided on the questionnaire, in the event of emotional distress, and participants were invited to utilize this information. They were also given the phone number and email of the PI in case they wished to have a personal contact (i.e., if they were in distress or had questions about the study).

We estimated the observed power for mediation analysis (the main analysis in the study) based on Vittinghoff et al. (Citation2009), using the “powerMediation” package in R. The parameters were α = 0.05, b1 = 0.2 (expected association between modeling for thinness and self-esteem) and b2 = 0.3 (expected association between self-esteem and dieting behaviors). The analysis indicated that the observed power of the study was 88.06%.

Data analysis

Before performing the main analyses, we conducted Little’s Missing Completely At Random (MCAR; 1988) test to examine the pattern of missing data, which comprised 4.9% of the overall data. MCAR indicated that the data were missing completely at random, χ2(26) = 31.84, p = .198. To handle missing data, we used Rubin’s (Citation2009) Multiple Imputation procedure (using 10 imputed datasets) when using SPSS, and the Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) when estimating SEM-based models. We performed these analyses on data from 114 participants (32 girls in the intervention with mothers, 35 girls in the intervention without mothers, and 47 controls).

Next, to describe the pattern of associations between the study measures (BMI, maternal modeling of thinness, self-esteem, and dieting behavior), we conducted a series of Pearson correlations and presented means and standard deviations. To examine differences between the study groups (girls in the intervention with mothers, girls in the intervention without mothers, controls) at baseline, we conducted a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with study group as the independent measure and BMI and maternal modeling of thinness as the dependent measures. We did not perform a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) because BMI and maternal modeling for thinness were not related to the same latent factor (r = .07).

To examine differences over time (baseline/T1; post-intervention/T2; follow-up, 6-8 months after the intervention/T3) in self-esteem and dieting behavior as a function of study group, we ran two latent trajectory models using MPlus 8.3 Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). After recoding the study group measure into two dummy variables comparing the intervention with mothers with the other two groups, we estimated the intercept and slope of change over time (using the time matrix of pre-intervention, post-intervention, and follow-up) in self-esteem and dieting behavior (separately) and predicted these slopes by study group and BMI. Doing so enabled us to examine whether there were different slopes of change over time for different study groups, different BMIs, or both. We estimated model fit using the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker Lewis Index (TLI), and the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA).

Finally, to examine the hypothesis that self-esteem would mediate the link between maternal modeling for thinness and dieting behaviors, and that study group would moderate this mediation path, we conducted a mediation-moderation model using PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2013; model 59). To allow a discussion of directionality, we measured maternal modeling for thinness at T1, self-esteem at T2, and dieting behaviors at T3. In the model, maternal modeling for thinness served as the predictor (x), self-esteem as the mediator (m), dieting behaviors as the outcome measure (y), study group (dummy coded) as the moderator (w), and BMI as a covariate. We estimated the significance of moderated mediation paths using bias-corrected bootstrap analysis with 5,000 resampling cycles.

Results

Differences at baseline in main study measures and over time

displays Pearson correlation coefficients, followed by means and standard deviations. ANOVAs assessing differences at baseline in BMI and maternal modeling of thinness revealed no significant differences between groups in the baseline levels of BMI, F(2, 114) = 0.22, p = .80, or maternal modeling of thinness, F(2, 114) = 1.13, p = .33.

Table 2. Correlations between main study variables (with means and standard deviations).

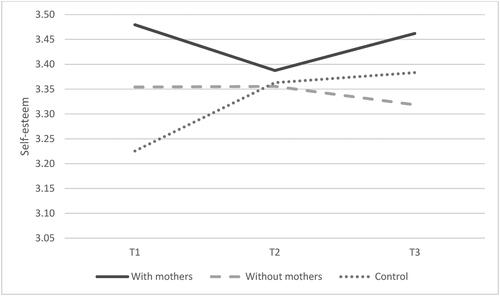

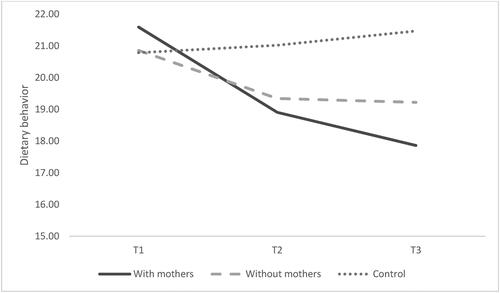

The latent trajectory models for assessing change over time in self-esteem and dieting behaviors showed an excellent fit to the observed data, χ2(6) = 6.85, p = .34, CFI = 1.00, TLI = .99, RMSEA = .04 for self-esteem (), and χ2(6) = 4.20, p = .65, CFI = 1.00, TLI = 1.00, RMSEA = .00 for dieting behaviors (). The models indicated that the self-esteem of the girls in the intervention group with mothers was marginally higher than that of the girls in the intervention group without mothers, specifically between T2 and T3, p = .06. Significant differences were revealed in the trajectory of change in dieting behaviors, a greater decrease being observed in the intervention group with mothers as opposed to a decrease in the other groups (p < .05). These effects were significant, controlling for BMI (which was not linked with the slope of change in self-esteem or dieting behaviors).

Association between modeling for thinness, self-esteem, and dieting behaviors

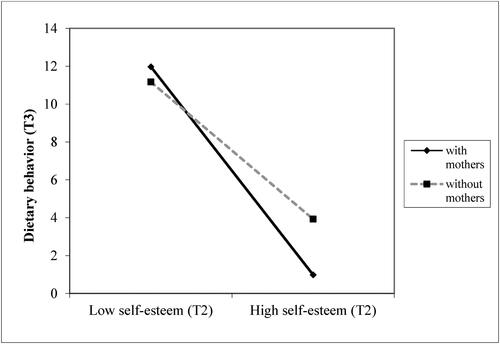

The analysis indicated that, as predicted, the higher the maternal modeling for thinness at T1, the lower the self-esteem at T2, b = −.22, β = −.30, p = .03. This link was not moderated by study group (ps > .23). Controlling for maternal modeling for thinness, self-esteem at T2 was associated with fewer dieting behaviors at T3, b = −4.55, β = −.46, p < .001. This link, however, was moderated by study group (intervention with mothers vs. intervention without mothers; b = 1.89, β = .19, p = .03). Simple slopes tests revealed that the link between self-esteem at T2 and dieting behaviors at T3 was significantly stronger for girls in the intervention group with mothers, b = −6.43, β = −.65, p < .001, than for girls in the intervention group without mothers, b = −2.68, β = −.27, p = .04 (). Overall, the analysis indicated that self-esteem significantly mediated the link between maternal modeling for thinness and dieting behaviors only for girls in the intervention group with mothers (indirect = .12, 95%, bias-corrected confidence intervals .01, .39).

Discussion

Our overall aims in the current study were to examine an intervention program for adolescent girls for preventing EDs and to identify risk factors that contribute to ED development. Our focus was on the mothers’ role in the outcomes of the prevention program. Therefore, we compared the girls who participated in the prevention program with their mothers vs. those who participated without their mothers, and vs. girls who were not exposed to the program (control group). Our main research hypothesis was that girls in the first intervention group (with mothers) would display significantly fewer dieting behaviors than those in the two other groups. We expected a positive change not only in attitudes toward DEPs, as has been shown in previous programs (Hart et al., Citation2015), but also in DEP behaviors. All research hypotheses were confirmed.

To the best of our knowledge, we are the first researchers to examine a face-to-face prevention program for DEPs that included an intervention group of girls and mothers who participated during the same time period but separately from each other (the girls during the school day, the mothers in the evening). We found, at the end of the intervention, that there was evidence of higher self-esteem among the girls who participated with their mothers than among those who participated without their mothers. Moreover, the higher the self-esteem of the participants in the former group, the less pathological their dieting behaviors. We found no significant differences in the relevant background variables between the two intervention groups. Participants in both groups were secular Jews with a high economic status.

Our evaluation of an ED prevention program for adolescent girls (an at-risk group) that integrated mothers into a parallel intervention is likely to make a contribution to the theoretical and practice global literature. Researchers have found that attempts to develop and implement programs for ED prevention have not yielded long-term behavioral changes (Hart et al., Citation2015), and it has been argued that effective programs for preventing EDs must focus on at-risk groups.

Mothers may contribute to the development of DEPs in their daughters (Hillard et al., Citation2016; Sadeh-Sharvit et al., Citation2016). By the same token, mother-daughter relationships may also be the best channel for the transmission of positive messages about body image and self-acceptance (Maor & Cwikel, Citation2016). Integrating mothers in a parallel prevention program may bring about the desired change. Yet, parents in general and mothers in particular have rarely been integrated in prevention programs (Hart et al., Citation2015; Hillard et al., Citation2016). Those programs in which parents have been integrated have involved only the mothers, without the participation of their daughters. To date, mothers have been targeted specifically in only one program (Corning et al., Citation2010). We would suggest, in accordance with our findings, that it is important to develop intervention protocols in which mothers play an integral part, so as to achieve consistent changes in their daughters’ behaviors.

More broadly, it has been shown that parents play a crucial role in the prevention of various emotional disorders in their children, such as anxiety, depression, and risky behaviors (Yap et al., Citation2015). In the last 50 years, parenting programs in a variety of fields have been extensively developed to maximize the benefits of parental influence on children’s development and mental health (Sandler et al., Citation2011). Programs based on parental involvement may exert a long-term influence on children’s health as they appear to lead to changes in the children’s emotional state (Rapee, Citation2013). Hence, our findings may be cautiously generalized to other areas of children’s and adolescents’ risky behaviors, attesting to the multidisciplinary relevance of our study. Parental involvement in their children’s lives has been positively correlated with children’s success and health (Berkowitz et al., Citation2021). That said, researchers have shown that parental engagement in school-based prevention programs is higher among high-income families than among low-income ones (Whittaker & Cowley, Citation2012). The mothers in the present study had a high socio-economic status, which may have influenced their willingness to participate in the program, and indirectly may have increased their influence on their daughters.

We found that the association between self-esteem and dieting behaviors in girls at follow-up (T3) was dependent on the intervention group to which they were assigned. As self-esteem increased, dieting behaviors became less pathological only in the intervention group with mothers. This finding contributes to the understanding of the prevention of DEPs in adolescents and how to identify at-risk groups. It also demonstrates the important role that mothers play in the prevention of DEPs. Maternal involvement in prevention can lead to changes not only in their daughters’ pathological attitudes, but more important, in their pathological behaviors, including dieting behaviors. A World Health Organization (WHO) survey of Jewish-Israeli adolescent girls revealed that they had the highest dieting tendencies among girls from 28 other participating countries (Harel et al., Citation2003). Another researcher found that 47% of Israeli youths ages 13-18 defined themselves as fat or overweight, and 45% wished to lose weight regardless of their objective weight, which was within the normal BMI range (Katz, Citation2013). As such, our findings attest to the importance of prevention programs for this population at high risk of developing eating disorders and, given the high rates of EDs worldwide, our findings have global relevance.

Our hypothesis about the association between maternal modeling of thinness and daughters’ self-esteem was fully confirmed: the higher the mothers’ modeling, the lower the girls’ self-esteem, and the more frequent the dieting behaviors among their daughters. These findings reinforce existing reports of the significant role mothers play in the formation of their daughters’ body image and in influencing their daughters’ eating behaviors through personal example (Handford et al., Citation2018; Hillard et al., Citation2016). In families in which an ED is present, there are also many family-level pathological eating characteristics, especially of the mothers (Arroyo & Andersen, Citation2016; Chow et al. Citation2018). Furthermore, mothers’ modeling of thinness has been associated with bulimic symptoms in daughters (Hillard et al., Citation2016).

Low self-esteem is one of the most significant risk factors for the development of EDs (Iannaccone et al., Citation2016). The negative association that we found between maternal modeling of thinness and daughters’ self-esteem expands the knowledge about the association between maternal modeling of thinness, negative body image, and DEP (Handford et al., Citation2018; Kluck, Citation2010). This association may contribute to the understanding of the risk factors involved in the development of EDs, as self-esteem may explain the association between maternal modeling and DEP. Our findings reinforce the need to develop ED prevention programs based on strengthening self-esteem.

Limitations and future research

Our study had several limitations. First, we focused on the risk factors likely to contribute to the development of DEPs and EDs, but did not examine EDs per se. Therefore, the findings should be interpreted cautiously with regard to the ED prevention program, although they are clearly helpful in identifying risk factors. Second, our sample was small and represented a relatively homogeneous population from Israel, with most participants having a middle-class background. It is therefore difficult to generalize from this sample to the rest of the population of the country, which is fairly diverse. Second, the findings are based on a homogeneous and “modern” Jewish-Israeli population. Going forward, researchers should investigate other populations in Israel, such as the Ultraorthodox Jewish population and the Arab population. Furthermore, our findings should be examined in light of the fact that differences have been found in the prevalence of EDs in urban areas vs. the periphery (Appolinario et al., Citation2022; Hay & Mitchison Citation2021). These differences can also affect prevention strategies. Third, the participating mothers were not assembled randomly, and respondents may have chosen to participate in the program because of their greater awareness of these types of eating-related problems. Fourth, because the questionnaires were not anonymous, there may have been an element of response bias; the girls may have been motivated to answer in a way they thought would please the PI. Fifth, participants were not examined to see whether they had an active ED, and their BMI was calculated based on their self-reported weight and height. These factors may have affected the accuracy and reliability of the data. Furthermore, we recommend that researchers in this field use a prescreening tool to ensure that individuals at risk (i.e., those with an existing ED or other psychological, social, or family problems) be identified before their participation in any intervention program. Participants in the present study were not screened before their participation, a factor that raises the ethical issue of whether the program could have potentially caused harm to this vulnerable population. It should be noted, however, that the "Full of Ourselves" program is based on strengthening one’s sense of empowerment and self-esteem, and promotes an intervention that places the highest value on the participation of the girls’ peer group (the girls were together with their peers during intervention sessions) and family. Consistent with the literature on this topic (Rohde et al., Citation2015; Stice et al., Citation2021), our overriding guideline was to "first do no harm.” Researchers have found that interventions that provide knowledge about EDs and body image may be harmful to girls with ED (Stice et al., Citation2013), but those that include the family and peer group can help these vulnerable girls in emotion regulation, stress relief, and the adoption of media literacy (McLean et al., Citation2017). We recommend that researchers, going forward, include different populations—that is, participants with no symptoms as well as those with symptoms. Last, the overall reliability of the program cannot be determined because the intervention was conducted by a single individual, the PI. A protocol should be constructed so that others can carry out the intervention and perform reliability analyses.

Study implications

We have described an innovative ED prevention program with an emphasis on mothers’ involvement. Our findings provide preliminary support for the implementation of an intervention model that includes face-to-face and parallel participation by daughters and mothers. Our main contribution, at both the theoretical and practical level, with both international and multidisciplinary implications, is in having captured the important role that parents, especially mothers, play in preventing EDs in their daughters. Such knowledge may be especially significant for professionals in the education system (teachers and guidance counselors), globally, who work regularly with children and adolescents. They could implement these programs routinely, integrating preventive efforts into the educational curriculum. Practitioners in the therapeutic professions (psychologists, social workers, and psychiatrists) may also benefit from the findings, implementing them in their clinical practice with mothers and daughters.

Our findings may have particular relevance for women in Israel and the Middle East. Middle Eastern society is typified by unique features of interpersonal communication, which include directness and informal relations (Aslani et al., Citation2013). Alongside the virtues of these characteristics (e.g., openness and warmth), there may also be some disadvantages, including directly insulting others, common among adolescents, which can lead to bullying. Bullying can have severe consequences for the mental state of adolescents, including psychiatric disorders such as EDs (Copeland et al., Citation2015). Working on empowerment and interpersonal relationships can improve these relationships, and educating people to be more assertive can help reduce abusive behaviors within the peer group.

Other study implications include a deepening of the knowledge of the influence of mothers’ attitudes and eating behaviors on their daughters. The significant effect that mothers have on their daughters should be taken into account by professionals who run prevention programs, globally, and such programs should be widely implemented. Our finding that maternal involvement in the intervention process promotes positive behavior (less dieting) in daughters suggests that the proposed model can be adapted to the prevention of risky adolescent behaviors in other areas. Maternal involvement may be the key to preventing such behaviors in a variety of domains.

Our findings make an important contribution to theory in the field of women’s health promotion in general and in the prevention of DEPs in particular. EDs are most prevalent in women and girls, and have a dominant transgenerational aspect, with correlations between mothers and daughters in their emotional health. Our choice of a model that stresses maternal involvement in preventive interventions with their daughters appears justified. Worldwide, mothers having a big influence on daughters, and mothers are an integral part of the process of changing their daughters’ harmful behaviors and promoting their health.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 BMI, calculated as weight (kg)/height-squared (m2), is the most commonly used measure for defining normal weight, obesity, and extreme thinness.

References

- Appolinario, J. C., Sichieri, R., Lopes, C. S., Moraes, C. E., da Veiga, G. V., Freitas, S., … Hay, P. (2022). Correlates and impact of DSM-5 binge eating disorder, bulimia nervosa and recurrent binge eating: a representative population survey in a middle-income country. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 57(7), 1491–1503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-022-02223-z

- Arroyo, A., & Andersen, K. K. (2016). Appearance-related communication and body image outcomes: Fat talk and old talk among mothers and daughters. Journal of Family Communication, 16(2), 95–110. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2016.1144604

- Aslani, S., Ramirez-Marin, J., Semnani-Azad, Z., Brett, J. M., & Tinsley, C. (2013). Dignity, face, and honor cultures: Implications for negotiation and conflict management. In Handbook of research on negotiation. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Balantekin, K. N. (2019). The influence of parental dieting behavior on child dieting behavior and weight status. Current Obesity Reports, 8(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-019-00338-0

- Berger, U., Wick, K., Brix, C., Bormann, B., Sowa, M., Schwartze, D., & Strauss, B. (2011). Primary prevention of eating-related problems in the real world. Journal of Public Health, 19(4), 357–365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-011-0402-x

- Berkowitz, R., Astor, R. A., Pineda, D., DePedro, K. T., Weiss, E. L., & Benbenishty, R. (2021). Parental involvement and perceptions of school climate in California. Urban Education, 56(3), 393–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085916685764

- Brun, I., Russell-Mayhew, S., & Mudry, T. (2021). Last Word: Ending the intergenerational transmission of body dissatisfaction and disordered eating: a call to investigate the mother-daughter relationship. Eating Disorders, 29(6), 591–598. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2020.1712635

- Cella, S., Iannaccone, M., & Cotrufo, P. (2020). Does body shame mediate the relationship between parental bonding, self-esteem, maladaptive perfectionism, body mass index and eating disorders? A structural equation model. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 25(3), 667–678. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00670-3

- Cheng, Z. H., Perko, V. L., Fuller-Marashi, L., Gau, J. M., & Stice, E. (2019). Ethnic differences in eating disorder prevalence, risk factors, and predictive effects of risk factors among young women. Eating Behaviors, 32, 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2018.11.004

- Chow, C. M., Tan, C. C., & Cin Tan, C. (2018). The role of fat talk in eating pathology and depressive symptoms among mother-daughter dyads mother-daughter research study view project A Dyadic perspective on parents’ feeding behaviors view project The role of fat talk in eating pathology and depressive symptoms among mother-daughter dyads. Body Image, 24, 36–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.11.003

- Cooper, P., & Stein, A. (2013). Childhood feeding problems and adolescent eating disorders (P. Cooper & A. Stein (Eds.)). Routledge. https://books.google.com/books?hl=iw&lr=&id=wcO3AAAAQBAJ&oi=fnd&pg=PR3&dq=Cooper+%26+Stein,+2013+eating&ots=ufDTllHfQo&sig=fRJ8LsluuDGWHqJyULYW84sXhQ0

- Copeland, W. E., Bulik, C. M., Zucker, N., Wolke, D., Lereya, S. T., & Costello, E. J. (2015). Does childhood bullying predict eating disorder symptoms? A prospective, longitudinal analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(8), 1141–1149. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22459

- Corning, A. F., Gondoli, D. M., Bucchianeri, M. M., & Salafia, E. H. B. (2010). Preventing the development of body issues in adolescent girls through intervention with their mothers. Body Image, 7(4), 289–295. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.08.001

- Cutting, T., Fisher, J., Grimm-Thomas, K., & Birch, L. (1999). Like mother, like daughter: familial patterns of overweight are mediated by mothers’ dietary disinhibition. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 69(4), 608–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/69.4.608

- Dakanalis, A., Clerici, M., & Stice, E. (2019). Prevention of eating disorders: current evidence-base for dissonance-based programmes and future directions. Eating and Weight Disorders: EWD, 24(4), 597–603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-019-00719-3

- Doumit, R., Khazen, G., Katsounari, I., Kazandjian, C., Long, J., & Zeeni, N. (2017). Investigating vulnerability for developing eating disorders in a multi-confessional population. Community Mental Health Journal, 53(1), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9872-6

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Fiissel, D. L. (2005). Using health promotion principles to prevent eating disorders in 8 to 10 year old girls: Uniting self-esteem, media literacy, and feminist approaches (pp. 4483). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/4483

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E. (2011). Social psychological theories of disordered eating in college women: Review and integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(7), 1224–1237. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.07.011

- Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Ciao, A. C., & Accurso, E. C. (2016). A naturalistic examination of social comparisons and disordered eating thoughts, urges, and behaviors in college women. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 49(2), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22486

- Galmiche, M., Déchelotte, P., Lambert, G., & Tavolacci, M. P. (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/nqy342

- Gardner, M., & Steinberg, L. (2005). Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: an experimental study. Developmental Psychology, 41(4), 625–635. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625

- Greenberg, L., Cwikel, J., & Mirsky, J. (2007). Cultural correlates of eating attitudes: A comparison between native-born and immigrant university students in Israel. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(1), 51–58. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20313

- Grogan, S. (2021). Body image: Understanding body dissatisfaction in men, women, and children. Routledge.

- Guest, E. (2016). Photo editing: Enhancing social media images to reflect appearance ideals. Journal of Aesthetic Nursing, 5(9), 444–446. https://doi.org/10.12968/joan.2016.5.9.444

- Handford, C. M., Rapee, R. M., & Fardouly, J. (2018). The influence of maternal modeling on body image concerns and eating disturbances in preadolescent girls. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 100, 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2017.11.001

- Harel, Y., Molcho, M., & Tillinger, E. (2003). Youth in Israel: Health, well being and risk behavior: Summary of findings from the third national study (2002) and trend analysis (1994–2002). Bar-Ilan University.

- Hart, L. M., Cornell, C., Damiano, S. R., & Paxton, S. J. (2015). Parents and prevention: A systematic review of interventions involving parents that aim to prevent body dissatisfaction or eating disorders. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(2), 157–169. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22284

- Hay, P., & Mitchison, D. (2021). Urbanization and eating disorders: a scoping review of studies from 2019 to 2020. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 34(3), 287–292. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000681

- Hayes, A. (2013). Mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. The Guilford Press.

- Hilbert, A., Pike, K. M., Goldschmidt, A. B., Wilfley, D. E., Fairburn, C. G., Dohm, F.-A., Walsh, B. T., & Striegel Weissman, R. (2014). Risk factors across the eating disorders. Psychiatry Research, 220(1-2), 500–506. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.05.054

- Hillard, E., Gondoli, D., Corning, A., & Morrissey, R. (2016). In it together: Mother talk of weight concerns moderates negative outcomes of encouragement to lose weight on daughter body dissatisfaction and disordered eating. Body Image, 16, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.09.004

- Hinojo-Lucena, F. J., Aznar-Díaz, I., Cáceres-Reche, M. P., Trujillo-Torres, J. M., & Romero-Rodríguez, J. M. (2019). Problematic internet use as a predictor of eating disorders in students: a systematic review and meta-analysis study. Nutrients, 11(9), 2151. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu11092151

- Hoek, H. W. (2016). Review of the worldwide epidemiology of eating disorders Article in Current Opinion in Psychiatry. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(6), 336–339. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000282

- Iannaccone, M., D’Olimpio, F., Cella, S., & Cotrufo, P. (2016). Self-esteem, body shame and eating disorder risk in obese and normal weight adolescents: A mediation model. Eating Behaviors, 21, 80–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2015.12.010

- Katz, B. (2013). Eating behavior and risks of eating disorders among adolescents in Israel. Mifgash Journal of Social Work and Education, 38, 9–30.

- Keski-Rahkonen, A., & Mustelin, L. (2016). Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 29(6), 340–345. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000278

- Keski-Rahkonen, A., Raevuori, A., & Hoek, H. W. (2018). Epidemiology of eating disorders: an update. Annual Review of Eating Disorders, 66–76. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315380063

- Kluck, A. S. (2010). Family influence on disordered eating: The role of body image dissatisfaction. Body Image, 7(1), 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.09.009

- Kronfol, Z., Khalifa, B., Khoury, B., Omar, O., Daouk, S., Dewitt, J. P., … Eisenberg, D. (2018). Selected psychiatric problems among college students in two Arab countries: comparison with the USA. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1718-7

- Lamb, M. E., & Lewis, C. (2013). Father-child relationships. In N. J. Cabrera & C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.), Handbook of father involvement: Multidisciplinary perspectives (pp. 119–134). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

- Latzer, Y., Spivak-Lavi, Z., & Katz, R. (2015). Disordered eating and media exposure among adolescent girls: The role of parental involvement and sense of empowerment. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 20(3), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/02673843.2015.1014925

- Latzer, Y., Witztum, E., & Stein, D. (2008). Eating disorders and disordered eating in Israel: an updated review. European Eating Disorders Review: The Professional Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 16(5), 361–374. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.875

- Le Grange, D., Lock, J., Loeb, K., & Nicholls, D. (2010). Academy for eating disorders position paper: The role of the family in eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(1), 1.

- Levine, M. P. (2019). Prevention of eating disorders: 2018 in review. Eating Disorders, 27(1), 18–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2019.1568773

- Levine, M., & Smolak, L. (2009). Recent developments and promising directions in the prevention of negative body image and disordered eating in children and adolescents. In L. Smolak & J. Thompson (Eds.), Body image, eating disorders, and obesity in youth: Assessment, prevention, and treatment (pp. 215–239). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/11860-011

- Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2005). Family-based treatment of eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 37(S1), S64–S67. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20122

- Lock, J., & Le Grange, D. (2019). Family-based treatment: Where are we and where should we be going to improve recovery in child and adolescent eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 52(4), 481–487. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22980

- Maor, M., & Cwikel, J. (2016). Mothers’ strategies to strengthen their daughters’ body image. Feminism & Psychology, 26(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353515592899

- Martini, M. G., Taborelli, E., Schmidt, U., Treasure, J., & Micali, N. (2019). Infant feeding behaviours and attitudes to feeding amongst mothers with eating disorders: A longitudinal study. European Eating Disorders Review: The Journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 27(2), 137–146. https://doi.org/10.1002/erv.2626

- McLean, S. A., Wertheim, E. H., Masters, J., & Paxton, S. J. (2017). A pilot evaluation of a social media literacy intervention to reduce risk factors for eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 50(7), 847–851. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22708

- Melisse, B., de Beurs, E., & van Furth, E. F. (2020). Eating disorders in the Arab world: a literature review. Journal of Eating Disorders, 8(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40337-020-00336-x

- Micali, N., Horton, N. J., Crosby, R. D., Swanson, S. A., Sonneville, K. R., Solmi, F., … Field, A. E. (2017). Eating disorder behaviours amongst adolescents: investigating classification, persistence and prospective associations with adverse outcomes using latent class models. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 26(2), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0877-7

- Mills, J. S., Shannon, A., & Hogue, J. (2017). Beauty, body image, and the media. In Perception of Beauty (pp. 145–157). Intechopen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.68944

- Moulding, N., & Hepworth, J. (2001). Understanding body image disturbance in the promotion of mental health: A discourse analytic study. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11(4), 305–317.

- Moy, G. (2015). Media, family, and peer influence on children’s body image [Doctoral dissertation]. Rutgers University-Camden Graduate School. https://doi.org/10.7282/T32R3TK0

- Murnen, S., & Smolak, L. (2019). The Cash effect: Shaping the research conversation on body image and eating disorders. Body Image, 31, 288–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.001

- Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Larson, N., Eisenberg, M., & Loth, K. (2011). Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(7), 1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012

- Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: engaging fathers–recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12280

- Rabinor, J. R. (1996). Mothers, daughters, and eating disorders: Honoring the mother-daughter. In Feminist perspectives on eating disorders (vol. 272). Guilford Press.

- Ragelienė, T., & Grønhøj, A. (2020). The influence of peers′ and siblings′ on children’s and adolescents′ healthy eating behavior. A systematic literature review. Appetite, 148, 104592. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2020.104592

- Rapee, R. M. (2013). The preventative effects of a brief, early intervention for pre-school aged children at risk for internalizing: Follow-up into middle adolescence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(7), 780–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12048

- Rauof, M., Ebrahimi, H., Jafarabadi, M. A., Malek, A., & Kheiroddin, J. B. (2015). Prevalence of eating disorders among adolescents in the Northwest of Iran. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 17(10), e19331. https://doi.org/10.5812/ircmj.19331

- Rohde, P., Stice, E., & Marti, C. N. (2015). Development and predictive effects of eating disorder risk factors during adolescence: Implications for prevention efforts. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(2), 187–198. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22270

- Rosenberg, M. J. (1965). When dissonance fails: On eliminating evaluation apprehension from attitude measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 1(1), 28. https://psycnet.apa.org/journals/psp/1/1/28/

- Rubin, D. (2009). Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Sadeh-Sharvit, S., Fitzsimmons-Craft, E. E., Taylor, C. B., & Yom-Tov, E. (2020). Predicting eating disorders from Internet activity. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(9), 1526–1533. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23338

- Sadeh-Sharvit, S., Zubery, E., Mankovski, E., Steiner, E., & Lock, J. D. (2016). Parent-based prevention program for the children of mothers with eating disorders: Feasibility and preliminary outcomes. Eating Disorders, 24(4), 312–325. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640266.2016.1153400

- Sandler, I. N., Schoenfelder, E. N., Wolchik, S. A., & MacKinnon, D. P. (2011). Long-term impact of prevention programs to promote effective parenting: Lasting effects but uncertain processes. Annual Review of Psychology, 62(1), 299–329. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.121208.131619

- Sanlier, N., Varli, S. N., Macit, M. S., Mortas, H., & Tatar, T. (2017). Evaluation of disordered eating tendencies in young adults. Eating and Weight Disorders-Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 22(4), 623–631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-017-0430-9

- Schaumberg, K., Anderson, D. A., Anderson, L. M., Reilly, E. E., & Gorrell, S. (2016). Dietary restraint: what’s the harm? A review of the relationship between dietary restraint, weight trajectory and the development of eating pathology. Clinical Obesity, 6(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.1213

- Schmidt, U., Adan, R., Böhm, I., Campbell, I. C., Dingemans, A., Ehrlich, S., … Zipfel, S. (2016). Eating disorders: the big issue. The Lancet Psychiatry, 3(4), 313–315.

- Sjostrom, L., & Steiner-Adair, C. (2005). Full of ourselves: A wellness program to advance girl power, health & leadership: An eating disorders prevention program that works. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 37, 141–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60215

- Smink, F. R., Van Hoeken, D., & Hoek, H. W. (2012). Epidemiology of eating disorders: incidence, prevalence and mortality rates. Current Psychiatry Reports, 14(4), 406–414. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0282-y

- Snoek, M., Van Strien, T., Janssens, M., & Engels, R. (2009). Longitudinal relationships between fathers. Mothers’, and adolescents’ restrained eating. Appetite, 52(2), 461–468. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2008.12.009

- Stice, E. (1998). Modeling of eating pathology and social reinforcement of the thin-ideal predict onset of bulimic symptoms. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(10), 931–944. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(98)00074-6

- Stice, E., Becker, C. B., & Yokum, S. (2013). Eating disorder prevention: Current evidence-base and future directions. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 46(5), 478–485. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22105

- Stice, E., & Desjardins, C. D. (2018). Interactions between risk factors in the prediction of onset of eating disorders: Exploratory hypothesis generating analyses. Behavior Research and Therapy, 105, 52–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2018.03.005

- Stice, E., Marti, C., & Durant, S. (2011). Risk factors for onset of eating disorders: Evidence of multiple risk pathways from an 8-year prospective study. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 49(10), 622–627. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2011.06.009

- Stice, E., Marti, C. N., Shaw, H., & Rohde, P. (2019). Meta-analytic review of dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs: Intervention, participant, and facilitator features that predict larger effects. Clinical Psychology Review, 70, 91–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.04.004

- Stice, E., Onipede, Z. A., & Marti, C. N. (2021). A meta-analytic review of trials that tested whether eating disorder prevention programs prevent eating disorder onset. Clinical Psychology Review, 87, 102046. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2021.102046

- Stice, E., Schupak-Neuberg, E., Shaw, H. E., & Stein, R. I. (1994). Relation of media exposure to eating disorder symptomatology: An examination of mediating mechanisms. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(4), 836. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.103.4.836

- Stice, E., Shaw, H., & Nemeroff, C. (1998). Dual pathway model of bulimia nervosa: Longitudinal support for dietary restraint and affect-regulation mechanisms. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 17(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.1998.17.2.129

- Tetzner, J., Becker, M., & Maaz, K. (2017). Development in multiple areas of life in adolescence: Interrelations between academic achievement, perceived peer acceptance, and self-esteem. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 41(6), 704–713. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025416664432

- Thomas, J., O’Hara, L., Tahboub-Schulte, S., Grey, I., & Chowdhury, N. (2018). Holy anorexia: Eating disorders symptomatology and religiosity among Muslim women in the United Arab Emirates. Psychiatry Research, 260, 495–499. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2017.11.082

- Thompson, J., & Schaefer, L. (2019). Thomas F. Cash: A multidimensional innovator in the measurement of body image; Some lessons learned and some lessons for the future of the field. Body Image, 31, 198–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.08.006

- Tiggemann, M. (2015). Considerations of positive body image across various social identities and special populations. Body Image, 14, 168–176. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2015.03.002https://repositories.lib.utexas.edu/handle/2152/2976

- van Strien, T., Frijters, J. E. R., van Staveren, W. A., Defares, P. B., & Deurenberg, P. (1986). The predictive validity of the Dutch Restrained Eating Scale. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 5(4), 747–755. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(198605)5:4<747::AID-EAT2260050413>3.0.CO;2-6

- Vander Ven, T., & Vander Ven, M. (2003). Exploring patterns of mother-blaming in anorexia scholarship: A study in the sociology of knowledge. Human Studies, 26(1), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022527631743

- Vittinghoff, E., Sen, S., & McCulloch, C. (2009). Sample size calculations for evaluating mediation. Statistics in Medicine, 28(4), 541–557. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.3491

- Weissman, R. S. (2019). The role of sociocultural factors in the etiology of eating disorders. Psychiatric Clinics, 42(1), 121–144. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psc.2018.10.009

- Whittaker, K. A., & Cowley, S. (2012). An effective programme is not enough: A review of factors associated with poor attendance and engagement with parenting support programmes. Children & Society, 26(2), 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1099-0860.2010.00333.x

- Wu, X., Kirk, S. F. L., Ohinmaa, A., & Veugelers, P. (2016). Health behaviours, body weight and self-esteem among grade five students in Canada. SpringerPlus, 5(1), 1099. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40064-016-2744-x

- Yap, M. B. H., Fowler, M., Reavley, N., & Jorm, A. F. (2015). Parenting strategies for reducing the risk of childhood depression and anxiety disorders: A Delphi consensus study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 183, 330–338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.05.031

- Zipfel, S., Giel, K., Bulik, C., Hay, P., Schmidt, U. (2015). Anorexia nervosa: aetiology, assessment, and treatment. The Lancet Psychiatry, 2(12), 1099–1111. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00356-9