Abstract

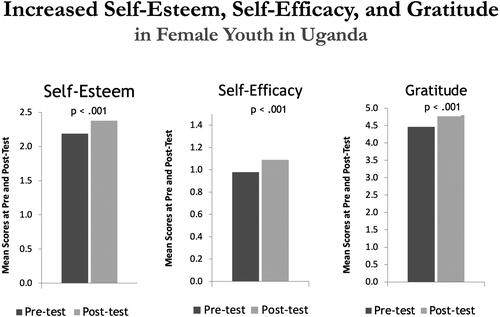

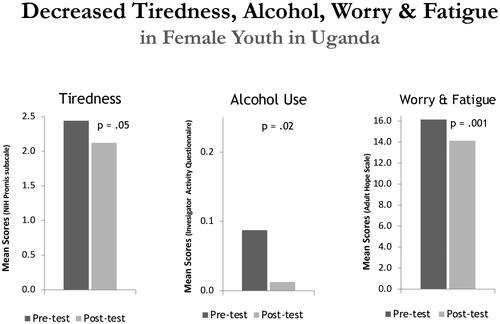

This longitudinal study with female youth in the slums of Kampala, Uganda (n = 130), explored the impact of the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique on self-esteem, the primary outcome measure, and self-efficacy, gratitude, hope, tiredness, and resilience as secondary outcomes. Quality-of-life behaviors were also assessed, including excessive alcohol use. After baseline testing participants learned TM over five consecutive days. Participants practiced TM at home for 20 min twice a day and attended two follow-up sessions. Post-testing occurred at five months. Significant improvements in self-esteem (p < .001), self-efficacy (p < .001), gratitude (p < .001), and tiredness (p = .05) were found. A decrease in excessive alcohol use was also observed (p = .02). At eight months a short answer questionnaire showed improved physical health, decreased stress and anxiety levels, and improved relationships in the family and community. Our findings have important implications for enhancing the well-being and empowerment of these vulnerable female youth.

This study involves female youth, age 13–26, who are living in poverty conditions in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. These young women are representative of the millions of women and girls living in poverty in the world, who face great challenges on a daily basis. We chose this age-range because they are at a critical stage in their growth and development, when they are exploring and developing their personal identity and self-concept that will guide them throughout their lives. Our focus on female youth in Uganda addresses the need to increase their well-being and empowerment. Our aim was to evaluate the potential of the Transcendental Meditation® (TM®) technique as a tool for organizations around the world, whose mission is to help empower young women with the ability to improve their quality of life. We propose that the TM program is a valuable modality to help female youth living in poverty to develop empowerment from within themselves, and to shift the challenging course of their lives toward a brighter future.

Background and setting

Uganda

The female youth in this study face many challenges to their mental and physical well-being, critical aspects of developing empowerment. Uganda’s recent history of considerable social tensions and violence, followed by the AIDS epidemic, has resulted in youth making up the largest proportion of the population in Uganda (Population Report, Citation2023, p. 13).

Of Uganda’s 17 million children under the age of 18, more than half live in slum areas. We chose to study female youth because the stress of dealing with the challenges they face can take its toll, resulting in low self-esteem, tiredness and low energy, and inability to cope. Researchers focusing on urban youth living in slum areas in Kampala have highlighted the many factors that create particular distress for adolescent girls and young women living in such challenging social environments. They face economic instability, food and shelter insecurity, limited access to education, lack of employment, gender disparities, and domestic and community violence (Swahn et al., Citation2022). Other critical challenges they face are a lack of proper sanitation in public latrines, and proper facilities and menstruation supplies for girls in schools (Kwiringira et al., Citation2014).

In Uganda there is a dire shortage of economic and human resources dedicated to mental health services and care for youth (Culbreth et al., Citation2021; Iversen et al., Citation2021; Swahn et al., Citation2022). Stella Ayerango, leader in the Young African Women’s Council, Uganda chapter, points out that despite achievements in her country, there are still challenges, including limited and/or no access to good quality education and primary health care for women (Klomegah, Citation2022). Young women require knowledge and resources to help them improve their mental and physical well-being and develop their full potential to be all they can be.

Our collaborators

This investigation was undertaken in collaboration with two organizations: African Women and Girls Organization for Total Knowledge (AWAGO) under National Director Judith Nassali, and Empowered Women, a community organization under Founder and Director Goreti Katana in the village of Kamwokya in the Kampala District. Funding was provided by the Rona and Jeffrey Abramson Foundation. AWAGO is an organization licensed and incorporated by the government of Uganda in 2011. Nassali explains that AWAGO’s mission is to serve women and girls in Uganda through the delivery of the evidence based Transcendental Meditation program to help them reduce stress and improve their mental and physical well-being. Empowered Women is a licensed community organization registered with the Uganda Registrations Services Bureau (URSB) in 2014. They serve women and girls in the urban slum areas of Kampala, with programs that include workshops and training for social well-being, skills development, economic empowerment, leadership training, and most recently AWAGO’s training in TM. This research was part of an ongoing project between AWAGO and the Empowered Women organization, where approximately 1000 members have learned TM to date.

Katana and other leaders of her organization were the first of their group to be introduced to the TM program by AWAGO in 2020. The immediate benefits they experienced inspired them to include TM in their training programs and to offer the TM program to all their members.

Katana has explained the challenges faced by female youth in her organization, which include lack of finances and school dropout. Dropout is usually due to separation of parents or to pregnancy. The Empowered Women youth members who are married have the challenge of often being left on their own, as men tend to use these girls and dump them after they give birth. They are left without support for their children. Since they are also still young, many live with their parents, and this lack of independence can cause conflicts, with abuse from parents who condemn them for giving birth so young. These challenges all point to a lack of empowerment in our participants that led us to our determination of our research measures: self-esteem, self-efficacy, gratitude, tiredness, hope, and resilience.

Self-esteem: Our primary outcome measure and important element of empowerment

Based on the literature and on our interviews with our collaborators, we chose measures that are indicative of the development of empowerment from within, including self-esteem, self-efficacy, and gratitude. Self-esteem, the primary outcome measure in this study, plays an important role in the lives of female youth living in the slum areas of Kampala, Uganda, as self-esteem is an important indicator of mental wellness and psychological well-being (Çiçek, Citation2021; Renzaho et al., Citation2020). Self-esteem enhances self-empowerment and aids individuals to maintain psychological health under forced situations (Baumeister et al., Citation2003). Self-esteem also plays an important role in how a person perceives themself. Individuals with high self-esteem believe that they are people of worth, and thus have a sense of respect for themselves (Lee et al., Citation2014; Rosenberg, Citation1989/1965). Conversely, low self-esteem involves a low overall evaluation of the self, persistent feelings of inferiority, a sense of worthlessness, and often, feelings of loneliness and insecurity (Çiçek, Citation2021; Mruk, Citation2006). Self-esteem correlates to happiness (Baumeister et al., Citation2003), increased agency—one’s feeling of a sense of control over one’s actions and their consequences, and positive social connection (Joshanloo, Citation2022). Young people’s evaluation of their own worth translates into increased self-acceptance or a sense of pride and dignity, and positive self-esteem encourages adolescents to be in their own values and beliefs and to make the right decisions in times of pressure (Renzaho et al., Citation2020). Self-esteem acts as a protector while exploring the world, and as a support while emerging as an adult (Seema & Kumar, Citation2017).

Alexander et al. (Citation1991), found that the TM technique increased self-actualization, which according to psychologist Abraham Maslow (Maslow, Citation1943), is one’s drive and ability to be one’s personal best.

Hypothesis

Our primary hypothesis was that after learning TM, self-esteem, our primary outcome measure, would increase in female youth living in poverty in the slums of Kampala, Uganda over a five-month period. Secondly, we hypothesized that self-efficacy (one’s perceived ability to cope with challenges in daily life), gratitude, hope, and resilience would increase, and that tiredness would decrease over a five-month period. Lastly, we hypothesized that quality of life behaviors such as alcohol use would decrease.

Theoretical context and significance

This research on the impact of the Transcendental Meditation technique for developing empowerment in the lives of female youth living in the city slums of Uganda, is based on a unique Theory of Empowerment from Within. It postulates that true and lasting empowerment is not ‘based’ on economics, nor is it ‘based’ on acquiring skills and developing capacities to enable economic improvement. It is not ‘based’ on building awareness of essential issues, or through counseling. Most importantly, empowerment is not something that can be bestowed by others. This Theory of Empowerment from Within postulates that empowerment that transforms women’s lives and society must come from a deep core level within the individual.

Historical overview

The word ‘empower’ is not new and arose in light of the long standing historical societal mileu of ‘disempowerment’ of individuals in society. ‘Disempowerment’ implies dominion over, power over, or zero sum model in which certain individuals hold power over others, implying a hierarchy of superiority. Wehmeyer and Cho (Citation2010) give a historical overview of the use of the term:

…the word empower is not new, having arisen in the mid-17th century with the legalistic meaning ‘to invest with authority, authorize.’ Shortly thereafter it began to be used with an infinitive in a more general way meaning ‘to enable or permit’…It’s modern use originated in the civil rights movement, which sought political empowerment for its followers. The word was then taken up by the women’s movement, and its appeal has not flagged. (p. 1–8)

As a new consciousness of women’s rights emerged, the concept of empowerment has become institutionalized globally with priorities and goals of organizations and agencies such as those of the United Nations that reflect the need to address the challenges faced by women, primarily in developing countries around the world. These needs are reflected in the UN Sustainable Development Goals which include gender equality, poverty removal, and women’s health and education. The 2023 UN Women Feminist Climate Justice report focused on the challenges of climate change on empowerment of women: (a) by 2050, climate change will push up to 158 million more women and girls into poverty and lead to 236 million more women into hunger; and (b) that the climate crisis fuels escalating conflict and forced migration, in a context of exclusionary, anti-rights political rhetoric targeting women, refugees, and other marginalized groups (Turquet et al., Citation2023, p. 7). UN Women point out that women and girls face greater health and safety risks as water and sanitation systems become compromised.

Neema (Citation2015) points out that “since development encompasses all spheres of life, the term empowerment evolved and came to be used widely in economic, political, socio-cultural and welfare contexts” with a focus on “economic issues and control of resources, overcoming inequalities in political participation, gaining decision-making power, and developing capacities to overcome obstacles in order to reduce structural gender inequalities.” Bandiera et al. (Citation2020) researched the impact of women’s empowerment programs for women in Uganda, indicating three key dimensions: political, economic, and control over one’s body. We can think of these contexts as external factors that impact or reflect one’s level of empowerment.

Other researchers have described empowerment as a process. Mahmud et al. (Citation2012) offer a general definition that: “empowerment broadly means having increased life options and choices, gaining greater control over one’s life, and generally attaining the capability to live the life one wishes to live” (p. 611). Kabeer (Citation2001) offers a definition of women’s empowerment as “an expansion in the range of potential choices available to women so that actual outcomes reflect the particular set of choices which the women value” (p. 81), and further as “a dynamic process of change whereby those who have been denied the ability to make choices acquire such an ability” (Kabeer, Citation1999). Mahmud et al. (Citation2012) speak about the critical ability to gain access and control over resources—material, human, and social. These are ‘building blocks’ that define, support, or hinder women’s agency, and that these resources “determine the trajectory of the empowerment process” (p. 611). These definitions point to a process of change in the lives of individuals in their social environment.

Others have presented the internal aspects of empowerment. In the field of community psychology Rappaport (Citation1985) speaks of empowerment in this way:

Although it is easy to intuit, it is a very complex idea to define because it has components that are both psychological and political…it suggests a sense of control over one’s life in personality, cognition, and motivation. It expresses itself at the level of feelings, at the level of ideas about self-worth, at the level of being able to make a difference in the world around us, and even at the level of something more akin to the spiritual. (p. 17)

Clay (Citation1990) speaks about the importance of developing one’s inner potential and a state of happiness for personal empowerment:

…empowerment is the means by which an individual acquires the inner authority to act as a free and useful person. Qualities of inner empowerment include self-esteem, confidence, and respect for others…In a larger sense, personal empowerment means that a person has achieved—to some degree—his or her inner potential. This is the state of happiness and usefulness that every person seeks, which goes beyond what we call ‘mental health’ to actual sanity. On a very basic level, personal empowerment simply means that a person is in touch with his or her basic goodness, and also recognizes a similar goodness in others. With this awareness, it is possible to reach lasting mental stability. (p. 497)

In light of these internal definitions of empowerment, we infer that empowerment cannot be bestowed by others but always must come from within. Giving a woman food, a sewing machine, or money does not empower a woman. Such gifts may make western donors feel good about themselves, but do not necessarily empower the recipients (Zikaria, Citation2021). The international research organization Pathways of Women’s Empowerment (Pathways, Citationn.d.) sees empowerment as a journey, not a destination. It is crucial that donors and researchers consider (a) women’s lived experiences, (b) what enables women to embark on this journey of personal empowerment, and (c) what supports them to empower themselves.

The literature often places therapeutic counseling in the domain of empowerment from within because it deals with the mind. Although counseling and educating women about gender inequalities, finding ‘a voice,’ and how to improve their circumstances, are important aspects of empowerment, a second element is needed. To solve their problems women need tools to help them go beyond their problems.

A new Theory of Empowerment from Within

The Theory of Empowerment from Within presented here postulates that true and lasting empowerment is not based on anything external—all external factors require the development of inner factors. The big question is HOW to develop power within, the inner capacities, the inner strength, the personal well-being, and personal power, to promote change in one’s life and in the society in which one lives? We know that the individual is the basic unit of society. To change society, change must come from within the individuals who make up that society. Development of the inner life of the individual is the key.

This Theory of Empowerment from Within explains how every person, and in this investigation, particularly every woman, can develop empowerment from a core level of silence and power from within themselves. Our research study is based on this theory which utilizes the Transcendental Meditation technique as intervention. This theory has two major components: (a) Transcendence and (b) the Mind/Body Connection.

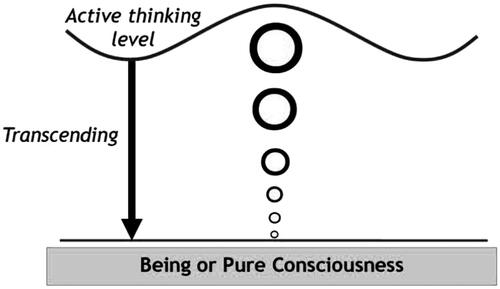

Component one: Transcendence

Component One is found in the name of our chosen intervention in the word transcendental. The mind has both an active and silent aspect. On the active surface level of the mind, we find ourselves engrossed in thinking about all the things going on each day, and all the daily events that pull us this way or that, as well as the stress of daily life that can takes its toll. The mind also has a ‘core self’ or ‘source of thought’ that can be experienced through the effortless and natural process of transcending during the TM practice (Roth, Citation2018).

The TM technique is described as an easy, effortless, and natural process in which the mind settles down to experience more quiet and subtle states of awareness, and finally to transcend all activity of the mind, to experience its natural, silent state within (Roth, Citation2018). The technique is characterized by (a) sitting comfortably with the eyes closed, (b) effortlessly thinking a mantra—a sound with no meaning, a factor that enables the technique’s success, (c) attention moving from the active, surface level of thinking and perception to more silent and abstract levels of thought, and (d) transcending or going beyond the conscious level of the senses, body, and mind, to rest in the silent, yet wakeful ‘core self,’ the field of transcendental consciousness, also referred to as ‘pure consciousness’ (Mahesh Yogi, Citation1969; Travis & Pearson, Citation2000). Pure consciousness is described as a state of fully awake inner self-awareness without the usual content of thoughts and perceptions. Travis and Pearson (Citation2000) describe this state:

Pure consciousness is ‘pure’ in the sense that it is free from the processes and contents of knowing. It is a state of ‘consciousness’ in that the knower is conscious through the experience, and can afterwards, describe it. The ‘content’ of pure consciousness is self-awareness. In contrast, the contents of normal waking experiences are outer objects or inner thoughts and feelings.

When we think of developing empowerment from within, we know that every action has its basis in thinking. What is the basis of thinking? Thinking has its basis in the field of ‘pure consciousness’ or inner Being, the transcendental field of consciousness. In his book Strength in Stillness, Roth (Citation2018) explains that the inner Being, the ‘source or thought’ or ‘pure consciousness’ is one’s quiet inner self. Through the experience of transcending during TM, the state of pure consciousness also called transcendental consciousness can be directly experienced. This experience of transcending develops individual consciousness at the fundamental silent yet lively source of consciousness within.

Transcendental consciousness is not a passive or trance-like state, but rather a state of restful alertness—mental quiescence with full inner wakefulness as explained by TM founder Maharishi Mahesh Yogi (Citation1969). Individuals find that contact with this inner silent, yet wakeful state results in greater clarity of mind, as well as greater physical vitality and energy in activity. In Uganda, Goldstein et al. (Citation2018) found that the TM technique reduced stress, increased physical vitality, and improved mental clarity in the lives of mothers living in extreme poverty conditions.

Researchers provide a clinical description of the state of restful alertness as a unique psychophysiological state gained during TM, distinctly different from the three known states of consciousness: waking, dreaming, and sleeping (Jevning et al., Citation1992; Travis & Wallace, Citation1999; Travis & Pearson, Citation2000; Wallace, Citation1970). These researchers have found unique physiological correlates during TM practice, such as decreased breath and heart rate, and increased skin conductance which indicate greater internal silence; and increased EEG coherence which reflects greater wakefulness and inner organizing power.

It is to be noted that the process of transcending differentiates the TM technique from other meditation techniques. Travis and Shear (Citation2010) have delineated three different types of meditation practices in terms of brain activity: (a) Concentration techniques, which generally involve focused attention typically correspond to gamma (20-Hz–50-Hz) EEG waves; (b) open monitoring techniques, including types of mindfulness practice that involve inward monitoring of thoughts and maintaining a non-judgmental attitude toward them, typically produce theta (4-Hz–8-Hz) waves; and (c) automatic self-transcending techniques such as TM which allow the mind to settle to quieter levels, primarily increase EEG alpha-coherence and synchrony, especially in the prefrontal cortex.

Mindfulness meditation involves both focused attention and open monitoring, with practices that intentionally focus attention on some particular thing such as the breath, the emotions, or physical sensations; whereas during TM emphasis is placed on the effortlessness with which a mantra (meaningless sound) is used to allow ‘automatic self-transcending’ (Rosenthal, Citation2016). Although mindfulness practices and Transcendental Meditation both have origins in ancient traditions, mindfulness from Buddhist tradition, and TM from Vedic tradition, the techniques are secular and non-religious practices utilized by individuals of all ages, walks of life, beliefs and cultures.

Pearson (Citation2013) points out that many people throughout the ages have described experiences or glimpses of the inner transcendental state that is so easily brought about by TM. What inhibits the ability to always have this experience of transcendental consciousness? The answer is: Stress. Stress is the inhibitor to experience and living the full value of the self, pure consciousness, in daily life, like clouds that cover our true essence. Rosenthal (Citation2012), utilizes the TM technique as a regular adjunct treatment modality in his clinical practice and finds that TM relieves stress and creates greater mind and body integration. This brings us to Component Two of our theory: The Mind/Body Connection.

Component Two: The mind/body connection

The mind and body are deeply connected. There are inseparable links between mental and physical health. What impacts the mind impacts the body, and what impacts the body impacts the mind (Nader, Citation2021, p. 28). It is widely known that psychological well-being impacts physical health and wellness as well as social life, occupational, educational, and spiritual life. It is also known that ‘rest’ is vital for mental and physical health, as ‘rest’ increases concentration and memory, reduces stress, improves mood, and contributes to a healthier immune system and better metabolism (Integris Health, Citation2021).

What are the mechanics of the Transcendental Meditation technique? When the mind naturally settles to a state of restful alertness during TM, the body also settles to this restful and alert state, allowing the body to release accumulated stress. ‘Stress release’ can be seen as a quieting of the fight-or-flight response triggered by stress (Barnes & Orme-Johnson, Citation2012; Dillbeck & Orme-Johnson, Citation1987; Walton et al., Citation2004). By reducing and eliminating stress one’s inner nature can be lived and shine.

Researchers have found that TM produces greater mind/body integration and rejuvenation by regulating cortisol and other hormones related to chronic stress (Infante et al., Citation2001). Rees et al. (Citation2013) found reduced PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Disorder) in Congolese refugees in Uganda. Researchers have also found TM enhances brain functioning, improving a person’s ability to cope, improving memory, moral reasoning, and problem solving, as well as one’s ability to perform and succeed (Travis et al., Citation2004; Travis & Arenander, Citation2006; Travis et al., Citation2009).

Researchers studying adolescents and young adults found that TM improved social-emotional learning and reduced psychological distress in African American students at a high risk high school (Valosek et al., Citation2019); improved health-related quality of life in three regional universities in Cambodia (Fergusson et al., Citation2019); reduced risk for hypertension among African American adolescents (Barnes et al., Citation2001, Citation2004, Citation2007); reduced psychological distress and increased coping in college students (Nidich et al., Citation2009); decreased cortisol stress hormone in a preliminary study with college students (Klimes-Dougan et al., Citation2020); increased self-esteem and reduced perceived stress, anxiety, anger, depression, and fatigue in high school students (Bleasdale et al., Citation2019); and improved ego development (Chandler et al., Citation2005). These studies, part of a body of research on TM, point to the positive impact of TM on the mental, physical, and emotional well-being for youth.

Theoretical significance

As we have discussed, this Theory of Empowerment from Within is based on the experience of transcending during TM which has been found to enhance and rejuvenate both mind and body for greater integration and balance in individual life. The basis of this growth is the experience of pure consciousness, which develops consciousness and human potential. This theory propounds to be a foundational key for establishing empowerment at the deepest level of oneself, and this new perspective fills the gap and elevates the existing literature on empowerment.

This Theory of Empowerment from Within:

Postulates that ‘economics’ alone does not create a foundation for developing empowerment in individual life. Although programs for economic empowerment are critical for women living in poverty, economic empowerment is not the ‘basis’ for building empowerment. The ‘basis’ must come from within the individual, through the strengthening of their own personal agentic qualities, creative problem solving, and motivation.

Expands on and fulfills Rowland’s perspective on power within, which she says is based on developing the ‘spiritual strength’ and uniqueness that resides in each of us. Spiritual strength has its ultimate basis in the integration of mind, body, and personality (Rosenthal, Citation2016). This Theory also brings fulfillment to the perspective of Clay (Citation1990), who emphasized the importance of developing one’s inner potential and a state of happiness and that personal empowerment means that a person has achieved—to some degree—his or her inner potential.

Allows capacity building and skills training to be nourished, enhanced, and strengthened. Evidence from Uganda suggests that the right combination of vocational and life skills training can dramatically improve adolescent girls’ livelihoods (World Bank, Citation2015). We postulate that the ‘right combination’ of life skills and capacity building, for the greatest success and positive outcomes, must include developing skill in action by accessing transcendental consciousness, a source of inner creativity, intelligence, and organizing power (Roth, Citation2018). Goreti Katana has shared that with TM, our research participants are more active, less lethargic, and have more energy to engage in activities. Youth who tended to run free are going back to school, and those who are not in school are more readily attending skills training programs.

Offers counseling programs a valuable tool to help strengthen the mind and emotions at a deep core level. Rosenthal (Citation2016) explains that many problems may percolate at different levels of our mind, like much unfinished business, but with the blissful peace of transcendence during TM, they become less bothersome, disturbing, or problematic. Researchers in Uganda found a decrease in psychological distress and an increase in coping in the lives of women living in poverty in the village of Kasangati Kazinga (Goldstein et al, in press). Local church leader and counselor Fausta Zadoch reported that after the introduction of the TM program in her area, there was a significant decrease in women and girls who came for counseling because “they are less stressed, and are improved spiritually, financially, and physically.”

Lastly, this research that is based on this Theory of Empowerment from Within is an important addition to the body of TM research, as it is the first TM study with female youth in low- to middle- income countries (LMICs).

Research methods

Participants

The young women participating in our study live in poverty conditions in the slums of Kampala, the capital city of Uganda, in the village of Kamwokya. The 130 participants in the study were female youth ranging in ages from 13 to 26. The Constitution of Uganda defines youth as any person between 18 and 30 years; the Ugandan Ministry of Gender, Labor, and Social Development define youth as ages 12–30 in its various programs; while the International Labor Organization (ILO) defines youth as any individual in the 15–24 age range (Renzaho et al., Citation2016). For this study our age criteria was 13–26, allowing an age range we felt was representative of these varied definitions. Four participants were excluded for not meeting the age criteria.

At the pretest 85% were between the ages of 13 and 19, with a mean age of 16.6 years (SD 3.195). 60% of participants had completed education to the primary level or less, and 30% were unable to read. Fifteen participants were mothers (see for demographic data).

Table 1. Demographic data.

Overview of participation

150 participants were assessed for eligibility with four being excluded for not meeting age criteria of 13–26.

146 completed the baseline testing.

16 participants did not return for post-testing at five months. As per Goreti Katana, Director of the Empowered Women organization, non-return reasons included: (a) parents lost jobs due to the pandemic and moved to their villages; (b) parents had separated disallowing girls to continue in the research; and (c) girls were no longer in school and were working.

Numbers analyzed at post-test: (n = 130).

114 (88% of the 130) returned to participate in the eight-month follow up questionnaire session.

Ethical considerations

Ethical considerations are very important to us, especially working with this young population. Prior to baseline testing, we obtained written informed consent from all participants, and for those under age 18, parental or guardian consent and approval was obtained. The consent form was read to every participant and to every parent or guardian, and they either signed their name for consent or marked their signature with a thumb print. AWAGO obtained additional written permission from parents or guardians to teach their children the TM technique, as per their standard procedure. Our study design and procedures were performed in line with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki, ensuring the well-being and safety of our participants. Procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of Maharishi International University prior to the starting date of the research. In addition, the Kampala Capital City Authority, Central Division, Kamwokya II Church Zone, was consulted with a request to conduct this research in their jurisdiction, and a signed document with their approval was obtained.

Translations

All research instruments were translated into Luganda, the language of the participants, utilizing the proper academic procedure with translations and back translations, under the guidance of the Alliance Francaise de Kampala language institute. In addition, leaders of AWAGO and Empowered Youth organizations reviewed all translations to ensure proper adaptation for this population.

Study design

This study utilized a longitudinal design to explore the effect of the Transcendental Meditation (TM) technique in the lives of female youth living in the city slums of Uganda. We chose a longitudinal design because we felt that at this time, with this age group, all of whom wished to learn TM, we wanted to preserve the comfort and feelings of the group, and thus chose not to perform a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT) with a waitlist control group, but rather to investigate changes in the one group over time. We will consider utilizing an RCT experimental design in future studies.

To begin the project, participants and their parents were invited to attend a meeting where they were provided a detailed explanation of the TM technique. Most of the parents were already practicing TM. All details of the project and the evaluation process were shared, and informed consent was obtained (see Ethical Considerations).

Participants were tested at baseline, and again after five months. The aim was to explore the impact of TM on self-esteem as the primary outcome; and self-efficacy, gratitude, hope, tiredness, and resilience as secondary outcomes. We also created questions asking participants about specific behaviors including alcohol and drug use, and the quality of behavioral interactions with children, partners, and neighbors. Eight months after baseline testing, a follow-up short-answer questionnaire was administered to participants. It included questions about TM adherence; changes in physical health, stress and anxiety; and changes in relationships at home and in the community.

Ugandan test administrators were recruited and trained by the primary investigator to ensure that all questionnaires were administered in a systematic, standardized, and consistent manner to eliminate potential bias. Since a significant number of the participants could not read and write proficiently, all questionnaires were administered in a question-and-answer format one-to-one. Data gathering thus took three days to complete. Test administrators asked questions simply without engaging in conversation, and questions were repeated up to three times as needed to give participants adequate time to comfortably answer. For efficiency and accuracy, test administrators used online data software to input responses. Upon completion of baseline testing, all participants took part in a 5-day course to receive instruction in the TM technique.

Intervention: The Transcendental Meditation technique

TM was chosen as the intervention for this research study because of the unique characteristic of transcending and its ease of practice and effortlessness. Judith Nassali, Executive Director of AWAGO points out that (a) TM can be learned by anyone of any age and culture, (b) TM is taught in Uganda by certified teachers according to the same standard and systematic manner throughout the world, validating its authenticity; and (c) TM has so far been taught successfully to over 30,000 people in Uganda with no adverse effects reported by AWAGO and its affiliate TM organization, Institute for Perfect Health, Uganda Ltd. headed by John Bukenya. Nassali says: “At AWAGO we have observed profound transformations toward greater empowerment in the women and girls whom we have taught, and this research study helps document our observations.”

Participants learned the standard TM technique from certified instructors over five consecutive days, approximately 90 min each day. Day One consisted of introductory and preparatory talks to inform participants about the TM practice, it’s benefits and how it works, followed by a short personal interview with the instructor. Day Two consisted of personal one-on-one instruction in the TM technique. Days Three, Four, and Five were group sessions for all who learned TM on Day Two, to provide further instruction, allow for questions and answers, and to check the correctness of practice. All participants were encouraged to practice the TM technique at home for 20 min twice a day for the duration of the study. To encourage participant engagement and enhance intervention adherence, two follow up sessions (60 min each) were held between baseline and post-testing to allow participants to ask questions about their TM practice, and to have a group checking of the correctness of practice.

Measures

Self-esteem, the primary outcome measure of this research study, was measured using the 10-item Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES) (Rosenberg, Citation1989/1965). This scale is designed to assess global self-esteem, which is defined as “the individual’s positive and negative attitude toward the self as a totality” (Rosenberg et al., Citation1995). Cronbach’s alpha for various samples are in the range of 0.77–0.88 (Blascovich & Tomaka, Citation1993; Rosenberg, Citation1986). The RSES was first presented in 1965 in Morris Rosenberg’s book Society and the Adolescent Self-Image (revised in 1989), based on his extensive, multi-layered research with 5024 students at ten high schools. Based on this research and subsequent validations by other researchers (Blascovich & Tomaka, Citation1993; Martín-Albo et al., Citation2007; Schmitt & Allik, Citation2005), the RSES has become the gold standard for measuring self-esteem, particularly in young people.

Self-efficacy was measured using the 10-item General Self Efficacy Scale (GSES) (Jerusalem & Schwarzer, Citation1995) with a total score designed to assess coping with daily hassles as well as adaptation after experiencing stressful life events. In samples from 23 nations, Cronbach’s alpha ranges from 0.76 to 0.90, with the majority in the high 0.80s. Response choices were adapted for this population using 1 = Not true, 2 = Somewhat true, 3 = Certainly true.

Gratitude was measured using The Gratitude Questionnaire (McCullough et al., Citation2002). This six-item form (GQ-6) is a self-report questionnaire designed to measure the disposition to experience gratitude in daily life. The GQ-6 has good internal reliability, and Cronbach’s alpha has been found to range between 0.82 and 0.87.

Hope was measured using the 12-item Adult Hope Scale (AHS) (Snyder et al., Citation1991). As recommended by Snyder, we called it The Future Scale. Cronbach’s alpha has been found to range from 0.74 to 0.84. The AHS is comprised of two subscales: (a) Agency (goal-directed energy) and (b) Pathways (planning to accomplish goals). These subscales include eight questions that were total sum scored according to AHS scoring guidelines. There are also four additional filler questions in the AHS. Three of these questions, 3, 7, and 11, were related to the physical and mental wellness elements of our study, so we also scored those items separately as a subscale. These questions were: (a) I feel tired most of the time; (b) I worry about my health; and (c) I usually find myself worrying about something.

Resilience was measured using the 2-item Resilience Scale (RISC) (Davidson, Citation2021). Questions were: (a) I am able to adapt to any changes that occur in my life, and (b) I tend to bounce back after illness, injury, or other hardships. Cronbach’s alpha has been found to range from 0.70 to 0.84.

Tiredness was assessed utilizing this question, from the NIH Promis (tiredness subscale): Over the past seven days I was too tired to enjoy the things I like to do, with response choices of never, almost never, sometimes, often, almost always.

Activity Questions were also created by the investigators to assess the frequency of certain behaviors of participants on a weekly basis. Questions were: How often per week do you…(a) yell at your children, (b) take recreational drugs, (c) consume alcohol, (d) fight with your spouse or partner, (e) argue with friends, relatives, or neighbors, (f) Consume alcohol to excess.

Eight-month follow-up questionnaire

For further assessment of the benefits of the intervention over time, a follow-up short-answer questionnaire was administered after eight months of TM practice. Questions included: (1) Regularity of TM practice with the following choices—I meditate regularly twice a day, I meditate twice a day most of the time, I usually meditate once a day, or I usually meditate less than once a day; (2) Have you noticed a change in your physical health since learning TM? (3) Have you noticed you are less stressed or anxious since learning TM? (4) Since learning TM have you noticed any change in how you relate to your family members? (5) Have you noticed any change in how you relate to your friends or neighbors? Questions 2–5 requested a yes/no answer, and if yes, to please describe. Again, due to a lack of literacy proficiency, testers were trained to administer the questionnaires in a question-and-answer format one-to-one with each participant. Testers asked the questions without any discussion, to avoid influence or bias. Data was inputted directly onto an online software platform.

Statistical analysis

Data was cleaned, and reverse scoring where appropriate, was performed. Published coding instructions for our measures were used for data analysis, which included instructions for reverse scoring. Skewness and kurtosis analyses confirmed a normal distribution for all questionnaire results. Data was analyzed for all questionnaires with paired samples t-tests to identify any changes that occurred from baseline to 5 months post-intervention. Data from 130 women was analyzed. Cohen’s d were calculated for effect sizes.

Upon completion of the 8-month follow-up questionnaire, responses were recorded and tallied regarding participants’ regularity of their TM practice, changes in physical health, changes in stress and anxiety levels, and changes in relationships at home and in the community ().

Research results

Outcome of baseline and 5-month intervention

Out of the original 146 participants, a total of 130 participants (89%) completed the 5-month post-test. The most significant results, following the TM intervention at five months, were an improvement in self-esteem, self-efficacy and gratitude (); and a significant decrease in tiredness (). We also found significant results on the Adult Hope Scale questions 3, 7, and 11, which we scored as a separate subscale. These again showed a significant decrease in tiredness/fatigue, as well as a decreased tendency to worry (). shows the mean scores, t and p value, as well as the effect sizes for each of the measures.

Table 2. Paired samples T-test comparisons of measures pre and post intervention.

All Activity Questions showed reduced frequencies from pre- to post-testing. The one question that showed a significant change within the group of women was How often per week do you consume alcohol to excess? Before the TM intervention, 10 women drank alcohol to excess one or more times per week. By the post-TM assessment, eight of the 10 reported a significant decrease ().

Outcome of follow-up questionnaire after 8-months

At eight months 114 (88%) participants returned to complete a short-answer follow-up questionnaire. They were asked about their regularity with their TM practice; changes in physical health, stress and anxiety; and changes in relationships at home and in the community. Responses were tallied as shown in .

Table 3. Changes in physical health, stress and anxiety levels, and relationships after eight months.

Compliance with the intervention was found to be high with 96 (84.2%) reporting practicing the TM technique regularly twice a day, seven (7%) reporting practicing once a day, and eleven (9.6%) reporting practicing less than once a day.

Changes in physical health, stress and anxiety levels, and relationships with family and community

Physical health: 101 (89%) participants reported improvement in their health. Comments included: stronger and healthier, energetic, calm and clear mind, feeling and looking good, and greater self-esteem.

Stress and anxiety levels: 112 (98%) participants reported decreased stress and anxiety. Comments included: calm and clear mind, less stressed, feeling and looking good, greater focus and improved memory, greater resilience, and feeling free.

Relationships with family: 112 (98%) participants reported improvement in relationships with family members. Comments included: able to relate to people better, greater cooperation and communication, feeling at peace, kinder, more open to other perspectives, able to calm myself down in a stressful situation, and not resorting to verbal or physical violence anymore.

Relationships with friends and neighbors: 100 (88%) participants reported improvement in relationships with friends and neighbors. Comments included: more friendly, improved communication skills, better cooperation, and greater ability to relate to people; more at peace and connected with my community, and more social; able to forgive and move on, more patient and resilient during unpleasant encounters, happier, calmer, less irritable, and more adaptable.

Quotes from participants on benefits of their TM practice:

I have improved in health and mentally, and even other people notice the change in me. After meditating I feel free, and my ability to do work has increased. I have improved in class performance and my relationship with others has also improved. I can control myself better now. NS age 16

Everything felt so hard before. I have six sisters and they all have kids. I was tired of struggling on my own, so I, too, decided to get pregnant and go into marriage. I had given up on my goals but that was until I learned TM. Meditation made me strong. It empowered me to realize I can push on in the face of adversity. JT age 19

I dropped out of school after my senior three. I am now married and have a child. I used to worry a lot and get into arguments all the time. After meditating consistently, I feel less worried. I do not get into arguments anymore. I even have more time to pursue my goals. Currently, I am enrolled in a hairdressing course. NJ age 21

I am a single mother of three boys. Before learning TM, I was constantly worried about supporting my family. But that has changed now. I feel much stronger and more confident in my ability to provide for my family. MA age 26

Discussion

The Theory of Empowerment from Within brings salience to our research which has self-esteem as the primary outcome measure. Rosenberg (Citation1989/1965) defines self-esteem as a positive or negative attitude toward a particular object, namely, the self. He continues to say that the ‘self’ is fundamentally the most important object in the world:

Whatever the self is, it becomes a center, an anchorage point, a standard of comparison, an ultimate real. Inevitably it takes its place as a supreme value. The self may vary in salience, but it is hard to imagine someone to whom the self is unimportant. (p. 9)

In his book One Unbounded Ocean of Consciousness Dr. Tony Nader (Citation2021), M.D., PhD, expands on the importance of understanding pure consciousness. He says that ancient knowledge available in Veda, particularly in Vedanta, “describes the source of all the physical and material as a field of consciousness.” He thus postulates that consciousness is not something created by matter or the brain, but that Consciousness is Primary and all there is. He points out that many philosophers, thinkers, and scientists throughout history and in recent times postulated similar concepts (p. 11). Quantum physicist Dr. John Hagelin (Citation1987) equates the Unified Field described mathematically in the string theory of physics with the field of pure consciousness:

The Unified Field, as we understand it today, is an abstract, unbounded ocean of pure existence, which—though eternally unchanging—is a field of infinite creative potential that gives birth to the universe and everything in it. In the deeply silent, maximally expanded state of transcendental consciousness, an individual’s awareness experiences, and identifies with, the universal intelligence of the Unified Field.

Our research points to the value of Transcendental Meditation: (a) to promote transcendence to bring about a settling of the mind and body to experience of the state of transcendental consciousness, a state of restful alertness, (b) to promote rejuvenation of mind and body through the release of deep stress, and (c) to allow one’s essential nature, pure consciousness, to be lived and shine. Our significant outcomes indicate greater empowerment in the lives of our female youth participants, age 13–26.

Self-esteem, our primary outcome measure, improved significantly following only five months of TM practice (). According to Rosenberg (Citation1989/1965) self-esteem is considered a critical lens for evaluating mental wellness in adolescents and youth, and for building empowerment at a critical age. He points out that the topic of self-image continues to change throughout life, but adolescence and youth is a particularly interesting time of life for studying it. Adolescence is a period when an awareness of and concern with self-image tends to be high, and when self-image is so vitally implicated in important life decisions and actions. After eight months of practice participants further reported that they feel stronger and healthier, feel and look better, have more energy, are calmer and more peaceful, and are more friendly and better able to communicate with others (). These results indicate that the TM practice allowed participants to develop a more positive attitude toward themselves and their environment.

Self-efficacy, as measured by the General Self-Efficacy Scale (GSES), also increased in our participants (). Self-esteem and general self-efficacy are considered two distinct, yet correlated self-evaluation constructs (Bandura, Citation1997; Chen et al., Citation2004; Joshanloo, Citation2022; Judge & Bono, Citation2001). Self-esteem is a person’s view of their self-worth—whether they have a positive or negative attitude toward themself, while self-efficacy is one’s perceived ability to perform actions that lead to desired outcomes. These two together are predictors of affective well-being (Joshanloo, Citation2022).

Research studies on empowerment often measure or address self-efficacy (Lindon, Citation2010; Murphy & Murphy, Citation2006; Posadzki et al., Citation2010). In his Social Cognitive Theory, Albert Bandura (Citation2001) suggests that people are not just passive recipients of their life circumstances, but rather they are active and agentic contributors, capable of influencing the nature and quality of their life experiences by their actions. Joshanloo (Citation2022) points out that people who have high self-efficacy are goal-directed and can intentionally modify their environment to perform actions for intended life outcomes. People with high perceived self-efficacy set more demanding goals and favor opportunities for success. They exhibit optimism and self-esteem because they believe in their ability to achieve their goals and remain fully task oriented in the face of pressing situation demands (Bandura, Citation1997). Increased self-efficacy following TM practice thus indicates a greater ability of our participants to both achieve and cope with challenges in their lives. Improved self-esteem in our participants indicates that they have a stronger foundation for doing so.

Gratitude, as measured by the Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6), also increased in our participants (). Several researchers studying psychological well-being have shown the positive correlation between self-esteem and gratitude. They have found that grateful people experience higher levels of self-esteem (Lin, Citation2017; McCullough et al., Citation2002; Rash et al., Citation2011). There is also a connection between gratitude and happiness that is multi-dimensional—by producing feelings of pleasure and contentment, gratitude impacts overall health and well-being. Gratitude and self-esteem are both associated with happiness (Chowdury, Citation2019).

Gratitude is the human way of acknowledging the good things of life, defined as a positive emotional response that we perceive on giving or receiving a benefit from someone (Emmons & McCullough, Citation2004). Whether it stems from the acceptance of another’s kindness, an appreciation for the majesty of nature, or a recognition of the gifts in one’s own life, gratitude enhances nearly all spheres of human experience (Emmons & Stern, Citation2013). There is evidence that gratitude (as per GQ-6), is positively related to optimism, life satisfaction, hope, spirituality and religiousness, forgiveness, empathy and prosocial behavior; and negatively related to depression, anxiety, materialism and envy (McCullough et al., Citation2002). Our investigation revealed a significant increase in the gratitude score on the GQ-6 following TM. The practice of TM over a five-month period thus appears to have had a significant impact on our participants’ ability to see the good in life, despite their challenging circumstances.

The Adult Hope Scale (AHS) did not reach significance. It is possible that the AHS is not appropriate for this age group, and it is also possible that it did not capture signs of hope after only five months of TM practice. In a follow-up interview with Empowered Women leader Goreti Katana after one year, she shared her observations of participants. She stated that it was clear that these young women’s behaviors became more goal-directed and agentic, and that they exhibited a new level of hopefulness in their lives. Katana shared that:

Before TM girls were stressed, and when stressed they would run to be with boys and be distracted from their education, and now since learning TM, they are less stressed, less distracted by boys and are focusing on doing what is best for themselves.

Some who were drunkards are now focusing on working and on how they treat their children and husband. I see women becoming less reactive and more focused on what is relevant to what they want in their lives. There is less conflict in their families, they let go of things that are not relevant, focusing on the important issues, and moving forward. These women have goals, and they are looking at reaching those goals.

Self-esteem, self-efficacy, and gratitude, as well as growing hopefulness for the future, are all important factors for increasing empowerment. Looking at these measures altogether, we see a picture of wellness for female youth in Uganda that highlights the benefits of TM for developing empowerment from within. These are exciting outcomes, given the ease with which TM can be learned, and its accessibility for these women in Uganda despite their socioeconomic challenge. TM is a technique that these young women can use for themselves and by themselves anywhere, with total anonymity. These particular measures are all abstract social/emotional constructs that deal with an essential and subtle level of oneself and one’s social interactions. The significant outcomes we found on these measures indicate that the TM technique as an intervention is impacting these more abstract and essential areas of inner life. The important aspect here, as we discussed in our Theory of Empowerment from Within, is the transcendental state—the ‘core self’ beyond the active thinking level. Roth (Citation2018) explains that the regular practice of TM—taking us back to our core self—allows one to see situations in a clearer light and through a wider lens.

Given the positive outcomes on these measures, we were not surprised to find a significant reduction in alcohol use. Of the ten participants who reported excessive alcohol use, eight of them reported a marked reduction during the first five months of practice. We believe this corresponds to their growing ability to cope with challenges and engage in life. The work of previous researchers substantiates this finding, showing TM reduced cigarette, alcohol, and drug usage (Alexander et al., Citation1994; O’Connell & Alexander, Citation2014; Royer, Citation1994). In Uganda, researchers have found alcohol use to be prevalent among both boys and girls living in the slums of Kampala (Swahn et al., Citation2020). AWAGO and Empowered Women leaders explained that these female youth may not have felt comfortable reporting alcohol usage, given their age. Additionally, this research study took place on the heels of two covid lockdowns, during which time participants and their families were struggling for food and survival. Leaders of AWAGO and Empowered Women indicated that alcohol and drugs may not have been as easily accessible.

In line with our second component of our Theory of Empowerment from Within—the mind/body connection—we found a significant reduction in tiredness. Day to day life for the young women in this study is a struggle, and tiredness is a huge complaint. The stress of finding food, avoiding abuse, and trying to get an education leaves them feeling worn out, with a lack of energy and enthusiasm. Two questions on tiredness, one from the NIH Promis (Citation2024): I was too tired to enjoy the things I like to do; and one from the Adult Hope Scale: I feel tired most of the time, revealed a significant decrease in tiredness. Participants also reported increased calmness, strength, and energy during the day (). Two other questions from the Adult Hope Scale:

(a) I worry about my health; and (b) I usually find myself worrying about something also revealed a significant decrease. Self-reports of participants indicate that they are less stressed and anxious and have clearer minds with greater ability to focus.

We also found an important social impact in the lives of our participants, which appears to be related to their growing self-esteem. Participants reported that their TM practice changed their ability to engage socially, that they experienced overall improvement in relationships at home, with friends, and in the neighborhood. They reported having a greater ability to relate to people, greater cooperation and communication, greater friendliness and kindness, and a new connection with their community. Participants also reported less stress and anxiety, as well as less irritability, greater adaptability, and less tendency to lash out with verbal or physical violence ().

Rosenberg (Citation1989/1965) discussed that social factors which can determine self-values, are an important element bearing on self-esteem. There is a vital relationship between perceived social support, self-esteem, depressive symptoms, and one’s ability to be socially engaged (Lee et al., Citation2014). Individuals with low self-esteem often have distorted, negative perceptions of themselves, others, and their relationships (Baumeister et al., Citation2003). Low self-esteem may motivate social avoidance, thus impeding actual and perceived social support (Lee et al., Citation2014). Freitas and Leonard (Citation2011) point out that according to Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, love and belongingness is a fundamental human need that is especially important for women. According to Baumeister and Leary (Citation1995), humans have an innate drive to form and maintain at least a minimum quantity of significant and meaningful interpersonal relationships. Satisfying this need for love and belongingness leads to a variety of positive health effects, and conversely, the lack of love and belongingness leads to a variety of ill health effects. Social connection is associated with a host of psychological and physical health benefits (Thoits, Citation2011; Uchino, Citation2006), and social isolation is associated with ill health (Cacioppo & Cacioppo, Citation2018). It has been found that the higher one’s self-esteem, the lower one’s level of social anxiety (Seema & Kumar, Citation2017).

Our outcomes reveal important signs of developing empowerment from within, indicative of a dynamic process, enhancing mental, physical, behavioral, and spiritual well-being. These young women living in the slums of Kampala are growing in self-esteem, growing in self-efficacy—their ability to cope with challenges in their environment; and growing in gratitude—their ability to appreciate their environment and their place in it. They are physically and mentally stronger. Their growth of personal empowerment is the first essential ingredient for maneuvering within and impacting their social environment. Peace in the community begins with peace in the individual, and this is the basis for peace in the nation.

Strengths of this study include (a) the coherent infrastructure provided by the collaborating partners AWAGO and the Empowered Women organization, (b) our well-organized research team, and (c) our test administrators who had experience working with large groups of women in Uganda. These three factors allowed smooth execution of all research components. Other strengths are our high post-test return rate of 89% and the high rate of compliance to the intervention—with 84.2% reporting practicing TM twice a day and 7% reporting practicing once a day.

A potential limitation of this study was the wide age range. Despite our choice of an age range consistent with the definition of ‘youth’ in Uganda, the experience of school-age youth, compared to young women who are mothers and responsible for a family unit, is quite different. The longitudinal design was a potential limitation, as compared to a Randomized Controlled Trial (RCT), which may have provided even stronger evidence for the effects of the intervention.

Additionally, we found that the two-item Resilience Scale was not an appropriate questionnaire for this population, particularly the 2nd question: I tend to bounce back after illness, injury, or other hardships. The 10-item Resilience Scale may have provided more information regarding resilience for this particular group.

Future directions for research

We are encouraged by the promising results from this study to conduct further investigation with this population of female youth living in challenging conditions, to further explore the value of TM as a basis for empowerment. Future studies could involve the following: (a) use of an experimental design utilizing a Randomized Controlled Trial; (b) objective measures, including physiologically-based imaging utilizing a portable system such as fNIRS (functional near-infrared spectroscopy) to quantify blood flow within the brain during the TM practice (stress impacts blood flow to the brain); (c) social impact research, based on the fact that this study, as well as previous TM research with women and girls living in poverty in Uganda, shows positive changes in social relationships at home and in the community; and (d) research on substance abuse, which has been found to be an important issue for this population.

Conclusion

We found a significant increase in quantitative measures of self-esteem, self-efficacy, and gratitude, as well as a significant decrease in tiredness, and excessive alcohol use, in our female youth participants living in impoverished conditions in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Participants’ self-reports revealed reduced stress and anxiety levels, positive changes in physical health, and improved relationships with family, friends, and neighbors. Our conclusion is that the TM technique allows these female youth in Uganda to establish a foundation of personal empowerment, a shift toward a more positive sense of self, self-image, self-love, and self-worth. TM helped these young women to better cope with the challenges they face at a critical time in their development to adulthood. With the growth of self-esteem, our primary outcome measure, these young women gained a greater appreciation of their own ability to engage in and impact the world around them. This shift had its basis in the development of empowerment from within.

Our investigation also reveals that the TM program can provide an added advantage for any organization whose mission is to help empower female youth living in challenging environments. We have found that TM opens doors to greater personal growth and empowerment. This brings hope for these young women to establish a firm foundation for a positive future. If TM works so well for this population of female youth in Uganda, with such challenging life circumstances, the TM technique has great potential for helping young women everywhere.

Acknowledgements

We wish to acknowledge the dedication and hard work of our two collaborating organizations, the African Women and Girls Organization for Total Knowledge (AWAGO) and Empowered Women.

We wish to acknowledge the Rona and Jeffrey Abramson Foundation and Michelle Floh, CEO, for their continued support of TM programs for women and girls in Uganda.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

We certify that this manuscript has not been published elsewhere or submitted simultaneously elsewhere for publication.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, C. N., Rainforth, M. V., & Gelderloos, P. (1991). Transcendental meditation, self-actualization, and psychological health: A conceptual overview and statistical meta-analysis. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 6(5), 189–247.

- Alexander, C. N., Robinson, P., & Rainforth, M. (1994). Treating and preventing alcohol, nicotine, and drug abuse through transcendental meditation: A review and statistical meta-analysis. Alcoholism Treatment Quarterly, 11(1-2), 13–87. https://doi.org/10.1300/J020v11n01_02

- Bandiera, O., Buehren, N., Burgess, R., Goldstein, M., Gulesci, S., Rasul, I., & Sulaiman, M. (2020). Women’s empowerment in action: Evidence from a randomized control trial in Africa. American Economic Journal: Applied Economics, 12(1), 210–259. https://doi.org/10.1257/app.20170416

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman and Company.

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: An agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1

- Barnes, V. A., & Orme-Johnson, D. W. (2012). Prevention and treatment of cardiovascular disease in adolescents and adults through the transcendental meditation program: A research review update. Current Hypertension Reviews, 8(3), 227–242.

- Barnes, V. A., Pendergrast, R. A., Davis, H. C., & Treiber, F. A. (2007). Meditation lowers ambulatory blood pressure in prehypertensive African American adolescents. Ethnicity & Disease, 17, S21–S21.

- Barnes, V. A., Treiber, F. A., & Davis, H. (2001). Impact of Transcendental Meditation on cardiovascular function at rest and during acute stress in adolescents with high normal blood pressure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 51(4), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0022-3999(01)00261-6

- Barnes, V. A., Treiber, F. A., & Johnson, M. H. (2004). Impact of transcendental meditation on ambulatory blood pressure in African-American adolescents. American Journal of Hypertension, 17(4), 366–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjhyper.2003.12.008

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117(3), 497–529. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497

- Baumeister, R. F., Campbell, J. D., Krueger, J. I., & Vohs, K. D. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4(1), 1–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1529-1006.01431

- Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1993). Measures of self-esteem. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (3rd ed., pp. 115–160). Institute for Social Research. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-590241-0.50008-3

- Bleasdale, J. E., Peterson, M. C., & Nidich, S. (2019). Effect of meditation on social/emotional well-being in high-performing high school. Professional School Counseling, 23(1), 2156759X2094063. https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X20940639

- Cacioppo, J. T., & Cacioppo, S. (2018). The growing problem of loneliness. Lancet, 391(10119), 426. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30142-9

- Chandler, H. M., Alexander, C. N., Heaton, D. P., & Grant, J. (2005). Transcendental meditation and post-conventional self-development: A 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 17(1), 93–122.

- Chen, G., Gully, S. M., & Eden, D. (2004). General self-efficacy and self-esteem: Toward theoretical and empirical distinction between correlated self-evaluations. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 25(3), 375–395. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.251

- Chowdury, M. R. (2019). The neuroscience of gratitude and effects on the brain. https://positivepsychology.com/neuroscience-of gratitude/

- Çiçek, İ. (2021). Mediating role of self-esteem in the association between loneliness and psychological and subjective well-being in university students. International Journal of Contemporary Educational Research, 8(2), 83–97. https://doi.org/10.33200/ijcer.817660

- Clay, S. (1990). Patient empowerment. PEOPLE, Mid-Husson Peer Advocates.

- Corbett, J. M., & Keller, C. P. (2005). An analytical framework to examine empowerment associated with participatory geographic information systems (PGIS). Cartographica, 40(4), 91–102. p. https://doi.org/10.3138/J590-6354-P38V-4269

- Culbreth, R., Masyn, K. E., Swahn, M. H., Self-Brown, S., & Kasirye, R. (2021). The interrelationships of child maltreatment, alcohol use, and suicidal ideation among youth living in the slums of Kampala, Uganda. Child Abuse & Neglect, 112, 104904. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104904

- Davidson, J. R. T. (2021). Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale (CD-RISC) manual. Accessible at www.cdrisc.com.

- Dillbeck, M. C., & Orme-Johnson, D. W. (1987). Physiological differences between transcendental meditation and rest. American Psychologist, 42(9), 879–881. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.42.9.879

- Emmons, R. A., & McCullough, M. E. (Eds.) (2004). The psychology of gratitude. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780195150100.001.0001

- Emmons, R. A., & Stern, R. (2013). Gratitude as a psychotherapeutic intervention. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 69(8), 846–855. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22020

- Fergusson, L., Bonshek, A., Vernon, S., Pheuy, P., Samen, M., & Vanthorn, S. (2019). A preliminary mixed methods study of health-related quality-of-life at three regional universities in Cambodia. ASEAN Journal of Education, 5(2), 54–67.

- Freitas, F. A., & Leonard, L. J. (2011). Maslow’s hierarchy of needs and student academic success. Teaching and Learning in Nursing, 6(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.teln.2010.07.004

- Goldstein, L., Nidich, S., Goodman, R., & Goodman, D. (2018). The effect of transcendental meditation on self-efficacy, perceived stress, and quality of life in mothers in Uganda. Health Care for Women International, 39(7), 734–754. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2018.1445254

- Hagelin, J. S. (1987). Is consciousness the unified field? A field theorist’s perspective. Modern Science and Vedic Science, 1(1), 29–87.

- Infante, J. R., Torres-Avisbal, M., Pinel, P., Vallejo, J. A., Peran, F., Gonzalez, F., Contreras, P., Pacheco, C., Roldan, A., & Latre, J. M. (2001). Catecholamine levels in practitioners of the transcendental meditation technique. Physiology & Behavior, 72(1-2), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0031-9384(00)00386-3

- Integris Health. (2021). Why it’s important to allow yourself to rest. https://integrishealth.org/resources/on-your-health/2021/april/why-its-important-to-allow-yourself-to-rest

- Iversen, S. A., Nalugya, J., Babirye, J. N., Engebretsen, I. M. S., & Skokauskas, N. (2021). Child and adolescent mental health services in Uganda. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 66. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00491-x

- Jerusalem, M., & Schwarzer, R. (1995). General self-efficacy scale (GSE). APA PsycTests. https://www.religiousforums.com/data/attachment-files/2014/12/22334_285ebbd019ec89856493442b1b6f9154.pdf

- Jevning, R., Wallace, R. K., & Beidebach, M. (1992). The physiology of meditation: A review. A wakeful hypometabolic integrated response. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 16(3), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/S01497634(05)80210-6

- Joshanloo, M. (2022). Self-esteem predicts positive affect directly and self-efficacy indirectly: A year-long longitudinal study. Cognition & Emotion, 36(6), 1211–1217. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2022.2095984

- Judge, T. A., & Bono, J. E. (2001). Relationship of core self-evaluations traits—self-esteem, generalized self-efficacy, locus of control, and emotional stability—with job satisfaction and job performance: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.86.1.80

- Kabeer, N. (1999). Resources, agency, achievements: Reflections on the measurement of women’s empowerment. Development and Change, 30(3), 435–464. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-7660.00125

- Kabeer, N. (2001). Conflicts over credit: Re-evaluating the empowerment potential of loans to women in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 29(1), 63–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00081-4

- Klimes-Dougan, B., Chong, L. S., Samikoglu, A., Thai, M., Amatya, P., Cullen, K. R., & Lim, K. O. (2020). Transcendental Meditation and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis functioning: A pilot, randomized controlled trial with young adults. Stress, 23(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253890.2019.1656714

- Klomegah, K. K. (2022). Empowering young African women-OpEd. https://www.eurasiareview.com/22072022-empowering-young-african-women-oped/

- Kwiringira, J., Atekyereza, P., Niwagaba, C., & Günther, I. (2014). Gender variations in access, choice to use and cleaning of shared latrines; experiences from Kampala Slums, Uganda. BMC Public Health, 14(1), 1180. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1180

- Lee, C., Dickson, D. A., Conley, C. S., & Holmbeck, G. N. (2014). A closer look at self-esteem perceived social support, and coping strategy: A prospective study of depressive symptomatology across the transition to college. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 33(6), 560–585. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2014.33.6.560

- Lin, C. C. (2017). The effect of higher-order gratitude on mental well-being: Beyond personality and unifactoral gratitude. Current Psychology, 36(1), 127–135. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-015-9392-0

- Lindon, E. (2010). Effects of Transcendental Meditation on perceived self-efficacy of college students [Masters Thesis]. Trinity College.

- Mahesh Yogi, M. (1969). Maharishi Mahesh Yogi on the Bhagavad-Gita: A new translation and commentary. Penguin Books.

- Mahmud, S., Shah, N. M., & Becker, S. (2012). Measurement of women’s empowerment in rural Bangladesh. World Development, 40(3), 610–619. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.08.003

- Martín-Albo, J., Núñiez, J. L., Navarro, J. G., & Grijalvo, F. (2007). The Rosenberg self-esteem scale: Translation and validation in university students. The Spanish Journal of Psychology, 10(2), 458–467. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1138741600006727

- Maslow, A. H. (1943). A theory of human motivation. Psychological Review, 50(4), 370–396. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0054346

- McCullough, M. E., Emmons, R. A., & Tsang, J. (2002). The grateful disposition: A conceptual and empirical topography. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(1), 112–127. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.82.1.112

- Mruk, C. J. (2006). Self-esteem research, theory, and practice: Toward a positive psychology of self-esteem. Springer Publishing Company.

- Murphy, H. & Murphy, E. K. (2006). Comparing quality of life using the World Health Organization Quality of Life measure (WHOQOL-100) in a clinical and non-clinical sample: Exploring the role of self-esteem, self-efficacy and social functioning. Journal of Mental Health, 15(3), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638230600700771

- Nader, T. (2021). One unbounded ocean of consciousness: Simple answers to the big questions in life. Penguin Random House Grupo Editorial S.A.

- Neema, M. (2015). Women’s empowerment and decision-making at the household level: A case study of Ankore families in Uganda [Doctoral dissertation]. Tilburg University.

- Nidich, S. I., Rainforth, M. V., Haaga, D. A., Hagelin, J., Salerno, J. W., Travis, F., Tanner, M., Gaylord-King, C., Grosswald, S., & Schneider, R. H. (2009). A randomized controlled trial on effects of the Transcendental Meditation program on blood pressure, psychological distress, and coping in young adults. American Journal of Hypertension, 22(12), 1326–1331. https://doi.org/10.1038/ajh.2009.184

- NIH Promis. (2024). Patient-reported outcomes measurement information system. https://commonfund.nih.gov/promis/index

- O’Connell, D. F., & Alexander, C. N. (2014). Self-recovery: Treating addictions using transcendental meditation and Maharishi Ayur-veda. Routledge.

- Pathways. (n.d.). Pathways of women’s empowerment. https://archive.ids.ac.uk/pathwaysofempowerment/www.pathwaysofempowerment.org/index.html

- Pearson, C. (2013). The supreme awakening: Experiences of enlightenment throughout time—and how you can cultivate them. Maharishi University of Management Press.

- Population Report. (2023). Mindset change for a favourable population age structure: A prerequisite for wealth creation (p. 13). https://npcsec.go.ug/wp-content/uploads/2023/11/SUPRE-2023-.pdf

- Posadzki, P., Stockl, A., Musonda, P., & Tsouroufli, M. (2010). A mixed-method approach to sense of coherence, health behaviors, self-efficacy and optimism: Towards the operationalization of positive health attitudes. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 51(3), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2009.00764.x