Abstract

This article explores the construction of a national and supra-national culinary identity in Slovenia in the decades since its independence from Yugoslavia through the TV chefs Valentina and Luka Novak’s celebrity cookbooks. As they cook for the nation, they establish the idea of what is to be “Slovene” in post-socialism. Based on an analysis of the spin-off cookbooks from their popular TV series Love through the Stomach broadcast on Slovene television from 2009 to 2014, the paper discusses their complex navigation between various aspects of Slovenia’s history, as the chefs distance the cuisine from its Yugoslav past and explicitly reorient its food culture toward Central Europe. In doing this, they reflect and reinforce larger discourse shifts that have been taking place in Slovenia since the 1980s and through which its political and media elites prepared the ground for Slovenia’s entry to the EU in 2004, distancing themselves from its “Balkan” neighbors and embracing its European essence. This paper shows how such shifts can be reflected in culinary texts, such as cookbooks, contributing to the understanding of everyday food texts as political texts. The paper also demonstrates the role of the Slovene middle-class elite as culinary trendsetters in the post-socialist period.

1. IntroductionFootnote1

In 2009, the husband-and-wife team, Valentina Smej Novak and Luka Novak, the latter also known as the translator and publisher of chef Jamie Oliver’s cookbooks into Slovene, started a new cooking show on the Slovene private channel POPTV. Entitled Ljubezen skozi želodec [Love through the Stomach], the show ran for five seasons, and provided material for three eponymous spin-off cookbooks. Modeled on contemporary celebrity food cooking programs, the show combined Slovene traditional fare with classic family dishes, such as spaghetti, while also signaling culinary and other capital through the inclusion of various other European and non-European foods. The Novaks, who cooked as mother and father for their three children on TV, set out to inspire their audience not simply to cook and eat the way that their parents and grandparents had, but to create their own tastes, dishes and habits.

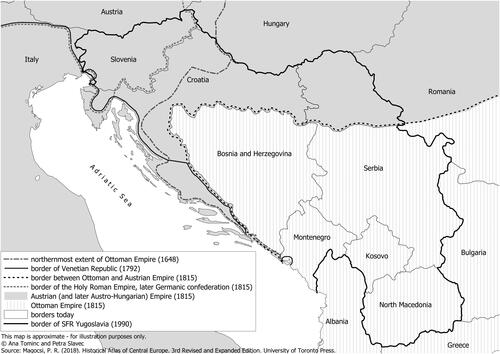

Part of their project was a reconfirmation of Slovene culinary identity as primarily Central European, while downplaying the cuisines of other parts of the former socialist Yugoslavia. Due to Slovenia being part of the Yugoslav federation between 1945 and 1991 dishes such as čevapčiči (minced meat kebabs) and sarme (minced meat and rice wrapped in cabbage) had become much loved dishes for all. Often casually referred to as ‘The Balkans’, the cultures of today’s nations to Slovenia’s south – particularly Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Kosovo and North Macedonia (see ) – have long been thought of in Slovenia as backward and uncivilized, reflecting Bakić-Hayden and Hayden’s (Citation1992, 4) concept of “nesting orientalisms” as “a tendency for each region to view cultures and regions to the south and east of it as more conservative or primitive”. The Novaks’ project demonstrates how such ideologies penetrate everyday life discourses, such as cooking, and how culinary texts, such as cookbooks, reflect and construct larger social, cultural and political ideas. Unable (or unwilling) to explicitly present the much-loved food of these Slovenia’s southern neighbors in negative terms, they frame it instead as food that belongs to the country’s past when it was part of Yugoslavia, while orienting themselves principally toward Slovenia’s pre-1918 history when it was part of the Austrian Empire, sharing its culture and perceived glamor. As they cook for the nation, they establish what it means to be “Slovene”: to eat foods of the former Yugoslav federation is old-fashioned, whereas to eat Wiener Schnitzel, Sachertorte and other – often common – specialties of the Austrian Empire, is to be European – it is who “we” are (and have always been) and, more importantly, it is who “we” wish to be again (cf. also Meršak Citation2014; Tominc Citation2014b).

Figure 1. Borders of the Habsburg and Ottoman Empires mapped onto former Yugoslavia (based on Magocsi Citation2018).

In demonstrating this complex reconfiguration of national and supra-national identity through an analysis of cookbooks, this paper contributes to the slowly accumulating work on the role of food and identity in Central and Eastern Europe, especially where identities have had to be reconstructed, reorganized, and, more recently, reshaped following the fall of the Eastern and Central European Communist regimes after 1989 (cf. Shectman Citation2009; Klumbyte Citation2010; Jung Citation2012; Bachorz Citation2019; Bachorz and Parasecoli Citation2023; and below for Yugoslavia). National cuisine is one of the seminal sites for the confirmation and maintenance of national identity, since, as Cusack (Citation2014, 66) remarks, “it seems to be a widely accepted part of the ideology of nationalism that every nation has its own cuisine, just as a nation has a flag or a national anthem”. Indeed, culinary texts have long been important spaces in which concepts and ideas around ‘the nation’ have been fought, supporting a particular ideological position about the state. In this ideological context, local/ethnic recipes can be selectively presented and assigned to the levels of the provincial, national or supra-national, and associated either with “us” or “them”. In this way, even the most similar culinary practices and tastes sharing centuries of history can be discursively separated and, on the contrary, those that may be joined only through the coincidence of a shared political border can be brought together (cf. Appadurai Citation1988; Helstosky Citation2003; Morris 2013; Parys Citation2013; Baron and Press-Barnathan Citation2021; Gaul Citation2022). It is no wonder, then, that cookbooks are political texts through which identities—regional, national and supra-national in particular—are purposefully created to signal an ever-elusive sense of belonging, and are, as such, important texts that speak to a nation’s cultural and historic ‘common sense’ sense of being (cf. Ferguson Citation2020).

In this paper, I seek to focus on the reconfirmation of a Slovene national (culinary) identity in cookbooks through the lens of the Novaks as elite celebrity chefs who act as the cultural intermediaries of acceptable taste in post-socialist Slovenia (Bourdieu [1979] Citation2009; cf. also Cusack Citation2014 for celebrity chefs and nation-building).Footnote2 Through such elite re-engagement and nostalgic, selective appropriation of the suppressed identities and tastes of the former Empire, now newly positioned as “high cultural capital” through the endorsement by the Novaks, and the downplaying of food that is increasingly seen as having “low cultural capital”, their cookbooks as media spin-offs signal to the nation the new “national” culinary position promoted by the elites. This is no longer bound to the official narrative of the Yugoslav “Brotherhood and Unity” slogan that sought during socialism to bind together an ethnically, linguistically and religiously diverse state. In this, the paper highlights the role of elites in post-socialist reconfigurations of national identity, demonstrating how the new elites’ interest in “denigrating all that has gone before, i.e. socialism,” as Hann (2014, 97) puts it discussing Slovenia’s neighbor, Hungary, is reflected in culinary discourse (cf. also Zarycki, Citation2009, for a similar process in Poland). Hann also shows how the new elites’ engagement in nostalgia for the Empire is a way of directing people’s “sentiments towards a pre-socialist past to which the present population has no direct connection” (ibid.).Footnote3 This provides the context for many national myths to be invoked in culinary discourse that contribute to the construction of a renewed national awareness, while the seemingly contradictory celebration of simple, “authentic,” and “traditional” food, with the simultaneous embrace of urban fusions of exotic and ethnic foods, places the Novaks squarely in line with contemporary Western foodie culture (Johnston and Baumann Citation2010).

Much like other global celebrity chefs, the Novaks promote cooking skills as much as they promote entertainment, pleasure, and indulgence, in which food features as part of a path to self-actualization. Food, for the Novaks, as for other celebrity chefs, is used in a kind of performance of “aestheticized leisure”, rather than to demonstrate a form of necessary domestic labor, even if this can never be excluded (Ashley et al. Citation2004; Bell and Hollows Citation2005). In approaching cuisine this way, the Novaks were participants in a larger explosion of lifestyle media, television shows, and books, which promoted new lifestyles and tastes among the Slovenes in a way that at the same time aligned their elite project to Western food trends, making their food both prestigious and accessible (cf. also Larsen and Österlund-Pötzsch Citation2012).

Some similarities can be drawn between the case presented here and that of other post-socialist European countries, rejecting and at the same time nostalgically longing for their replaced political systems (e.g. Ostalgie in the GDR). However, as more than three decades have passed since 1989, when the Berlin wall fell, it is becoming even clearer that the developments of these European countries have since “unravelled in so many different ways” (Caldwell 2009, 4). The case should thus be more accurately positioned among those countries that had both for centuries been part of the Habsburg Empire and, post-1945, experienced state socialism. Even among those, Slovenia is unique (as is Croatia) due to the exceptional status of Yugoslavia outside the so-called Eastern Bloc that, as part of the nonaligned movement, paved the way for its citizens to have a very different political and economic experience that allowed it to develop a comparatively more liberal consumerist society (cf. Luthar Citation2010; Patterson Citation2011; Jelača, Kolanović and Lugarić Citation2017; and especially on food in socialist Yugoslavia, Tivadar, Citation2009; Tivadar and Vezovnik Citation2010; Bracewell Citation2012; Tominc Citation2015, Citation2017, Citation2022; Vezovnik and Kamin Citation2016; Fotiadis, Ivanović and Vučetić Citation2019). In post-socialist culinary discourse in the former Yugoslav countries, however, much remains to be explored, in particular as tradition meets contemporary global trends, and national and other identities continue to be shaped and reshaped in response to populist and other political ideas (cf. Bajic-Hajdukovic Citation2013; Črnič Citation2014; Tominc, Citation2014b, Citation2017; Vučetić Citation2019).

In the rest of this paper, I first present a brief review of Slovenia’s culinary and political background, including the role of the post-socialist elites in the construction of a national culinary discourse. After methodological considerations, I discuss, through an analysis of the Novaks’ cookbooks, how Slovenia’s elite national culinary discourse is framed in historical narratives that either endorse or downplay parts of Slovenia’s culinary past and present.

2. From socialist Yugoslavia to post-socialist Slovenia: Reconfiguring the national culinary identity through celebrity chef cookbooks

2.1. Slovenia and its cuisine from the Habsburg Empire through socialist Yugoslavia to independence

Most of present-day Slovene territory was part of the multi-lingual, multi-ethnic, multi-faith Austrian (Habsburg) Empire for many centuries. As a distinct nation, Slovenia’s formation has its roots – like other Central European nations – in the 19th century ideology of Blut und Boden, where the concept of a nation was understood as a community of people related by “blood and soil”. From this, claims for special rights based on national (and language) identity sprang up across the Empire from the mid-19th century onwards, shaping from then on a distinct set of cuisines and identities. Due to centuries of entanglement with this Central-European cultural, political and economic context, much of Slovene food culture (especially that of the middle classes) was at the time de facto Austrian, the cuisine of the Empire’s middle-class elites, circulating in the Empire. In a passage of her novel Trieste the Croatian writer, Daša Drndić (Citation2014, 37), ironically captures the days of this Austrian “great and happy land” that illustrates the homogenizing force of the Empire and the comforting endearment of common products when they become linguistically domesticated. Across the entire Empire, she says,

the same products and the same brands are distributed, the same food items of equal quality, with only the names adapted discreetly to the language of each of the peoples:/…/Knödel become knedliky in Czech; the Wiener Schnitzel is called bečka in Croatia and in Italian, cotoletta Milanese. The distant centres of the Monarchy, its balls, waltzes and its coaches, schnapps and Sachertorte, its painters and its Imperial family, all this becomes intimate and dear in the provinces as soon as it is ever so slightly Italianized, Croaticized, Magyarized.Footnote4

Most of the rural population, however, ate mostly simpler, locally available foods, while the dishes that circulated through-out the Empire often reflected the urban cuisine of the better-off merchants and town-dwellers. These were represented in magazines and cookbooks, written in the various languages of the Empire for the needs of the growing urban population of middle-class housewives. For the Slovenes, the most important cookbook of the time was the Slovenska kuharica [The Slovene Cookbook], published in 1869 by Magdalena Pleiweis seen as the first original (non-translated) cookbook in the Slovene language. From this, a tradition emerged of “Slovene” cookbooks that supported how the newly emerging national identity could be imagined through food. From the early 20th century, a series of women food writers (many happened to be nuns), and, most importantly, Felicita Kalinšek, built on Pleiweis’ cookbook, appropriating the dishes of the Empire for the “national” cuisine. Soups, potatoes, meat dishes, and various desserts were increasingly represented as “Slovene” (Starec 2007), although the simpler tastes of regional rural populations such as various thick soups, were also incorporated as “Slovene” through time. This came to the forefront in culinary discourse particularly in the 1980s, laying the ground for the emergence of a more distinct national identity (from Yugoslavia) as Yugoslavia started to dissolve (cf. Vezovnik and Tominc Citation2019).

Following the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after the end of the First World War in 1918, the greater part of the Slovene lands was incorporated into the State, and later Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, which in 1929 renamed itself the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, headed by the Serbian House of Karađorđević until Hitler’s annexation in 1943. Except for Croatia, which, like Slovenia had formed part of first the Austrian and then the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the other parts of the new Kingdom emerged from the ashes of the Ottoman Empire which had been slowly decaying over the first decades of the 20th century until its dissolution in 1922. After the Second World War, following its successful resistance against the German Occupation, the second Yugoslavia – now a socialist federal republic – was formed in 1945, joining in one state several ethnicities, languages, religions and cultural (and especially culinary) traditions. For centuries these had been developed and shaped by two distinctly different, yet very powerful and influential European cultural contexts: one, Austrian, Catholic, ruled from Vienna, and the other one Ottoman, mostly Muslim, with its center in what is today Istanbul. While these two traditions to some extent interacted, shaping each other’s cultural and culinary repertoires, they also for centuries competed both for territory in the Balkans and influence in European politics, while othering each other for the benefit of their domestic political audiences (Samancı Citation2011; Baldwin Citation2018; Öztürk Citation2021). In the post-1945 Yugoslav federation, Slovene cuisine retained its national status, since the Yugoslav kitchen was not equipped with a melting pot, and culinary literature that was framed as explicitly Yugoslav hardly existed. Rather, dishes were commonly labeled with ethnic and regional terms and food texts were often devoted to regional or national cookery, such as ‘the Dalmatian kitchen’ or ‘Serbian cuisine’ (Caldwell 2012).

Slovenes have a long tradition of incorporating Central European foods, like Wiener Schnitzel, into their diets, with certain regions more heavily influenced by Hungarian and Mediterranean flavors. It was not until 1923 that the first Ottoman dishes, such as stuffed peppers, appeared in Kalinšek’s Slovenska kuharica for the first time. Slovene food culture came under further Balkan influence when it was re-integrated into socialist Yugoslavia. By the 1950s, a later edition of Kalinšek’s cookbook contained even more recipes from the Balkans for dishes like čorba, čevapčiči, moussaka, djuvečFootnote5 and several other dishes labeled as “Serbian” (Zevnik and Stanković Citation2011, 369). It is impossible to know to what extent these dishes featured on the tables of ordinary Slovenes, but it is likely that they became more common beginning in the 1960s and 1970s, when a large number of migrants from Serbia, Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Kosovo settled in Slovenia, bringing their tastes and food habits with them (Dolenc Citation2007, 79-85). Recipes for Balkan specialities such as stuffed peppers and sarme were likely exchanged at work or encountered in Slovene women’s magazines such as Naša žena [Our Woman]. Other dishes such as burek—a filled pastry of Turkish origin common throughout the Balkans—was sold as street food to hungry students and party-makers at all hours by Kosovan Albanians. Of all Balkan dishes in Slovenia, burek became the most laden with negative connotations, signifying foreignness, and, metaphorically, sometimes “stupidity,” “worthlessness,” and “dirtiness,” as well as other negative Balkan stereotypes (Mlekuž Citation2007).

Today, several dishes of Ottoman origin have lost the status of foreign, “immigrant”, or Balkan food altogether and are an important part of the Slovene foodscape (similarly to “Austrian” Apfelstrudel and Wiener Schnitzel).Footnote6 “Ottoman” culinary specialties such as čevapčiči, ražnjiči and pleskaviceFootnote7 are widely available at butchers’ shops and in supermarkets and are popular for summer outdoor parties and barbecues. Stuffed peppers, sarme, and čufteFootnote8 are considered everyday, common dishes. In the case of stuffed peppers, they have almost completely lost the status of a foreign dish, a change marked by the localization of the dish’s name into polnjene/filane paprike (stuffed peppers), much like Apfelstrudel has become jabolčni zavitek (apple roll). A recent study also demonstrates unequivocally that when asked about their everyday food habits, “nearly half of the Slovenian respondents stated without hesitation that they quite regularly eat dishes like pasulj (a thick bean soup), segedinar (a goulash-like stew prepared with pork and sauerkraut), stuffed peppers, sarmas and pleskavicas” (Zevnik and Stanković Citation2011, 367). As such, actual Slovene food tastes seem to challenge overarching, hegemonic representations of this culinary heritage as backward, unsophisticated and indeed, non-European (Zevnik and Stanković Citation2011). In fact, for many Slovenes, Balkan dishes evoke the old days of relative security and stability, as they nostalgically look back to the Yugoslav era when most people had a job, a house, and funds for holidays on the Croatian coast at least once a year, fueling the (Yugo)nostalgia for former regimes explored elsewhere in literature (e.g. Spaskovska Citation2008; Velikonja Citation2009; Bošković Citation2013).

Following Yugoslavia’s dissolution in 1991, Slovenia avoided the brutal wars of the 1990s that involved the other successor states and was the first to join the European Union in 2004. The political and economic path “back to Europe” from “Balkan Yugoslavia” was underway, but questions surrounding the nation’s identity remained. The existing negative attitudes toward Slovenia’s “southern” neighbors intensified during the wars of the 1990s when the Balkan and Yugoslav socialist past became an embarrassment, a kind of barrier to the re-formulation of national identity (Vezovnik Citation2009). While the international media tended to define the Balkans as the “Other,” noting the difference between “Europe” and the “backward” and “barbaric” Balkans, Slovenia’s Yugoslav past came to be seen as a “distortion to its European essence” in Slovenia itself and as an interruption of its European historical trajectory (Vezovnik Citation2009, 164). For the Slovenes to be European, the media began to insist, they must remove any remnant of ‘Balkanness’ in Slovene culture or identity. The “true” Slovene identity should lie in its pre-communist and even pre-interwar Yugoslav past, when the Slovene lands were part of the “civilized” and “cultured” Austrian Empire, away from the Balkan “Other,” seen as connected to the backward Ottoman past (Baskar Citation2007, 57-8; for a similar argument cf. also Šaver Citation2005; Velikonja Citation2005; Petrović Citation2009). This myth of Slovenia and Croatia belonging to “Central Europe” emerged in both countries from the 1980s on, much in line with the concept’s appearance in the rest of the countries of the former Empire and in Poland as a way of distancing themselves from the USSR and the Balkans:Footnote9 to be “truly” Central European “was always Western, rational, humanistic, democratic, sceptical and tolerant” (Ash, in Todorova [Citation1997] 2009, 153; Zorić Citation2013; Zarycki Citation2014).

2.2. Celebrity cooking, the middle class and the power of food media in the construction of national culinary identity

One of the most prominent culinary events in Slovenia post-2000s, as in many other countries, was the arrival of Jamie Oliver’s TV cooking shows on national television in 2001. It introduced local audiences to a positive and inspirational approach to cooking. Apart from foods that reflected its British historic and cultural context, the show embodied a new approach to TV cooking, with much more dynamic camera angles and a more relaxed approach to cooking and the presenting of food programs that was soon recognized as both business and camera-friendly by the local media and other elites. Successfully navigating the initial transformation of the 1990s, the Novak family, especially Luka and Valentina, were well positioned to take on the project of translating Oliver’s cooking, establishing through it middle-class preferences and taste, both anchored in tradition and reaching out toward global trends. From establishing and running their family publishing house, Vale Novak, where Luka was CEO, translator, and writer (and which they later sold), through running Totaliteta, a publishing business and press specifically dedicated to food, to briefly venturing into politics, their successes firmly represented the financially and socially well-connected elite strata of post-socialist society in Slovenia. Their TV show and cookbooks were nominated for and won several awards, demonstrating the extent of their impact and influence on Slovene media, with the cookbooks the best-selling nonfiction books of 2010 and 2011.Footnote10

The Novaks are representatives of the new, post-socialist middle class that emerged from an officially (but not de facto) classless society after 1991, where economic differences between segments of society already existed, although they were not as large or prominent as in the capitalist West (cf. Petrović and Hofman Citation2017). In such a context of general economic egalitarianism, Luthar (Citation2012) suggests cultural capital played a crucial role in creating cultural distinction in post-socialist Slovenia, as non-material cultural markers (e.g. knowledge of food, fashion, literature and so forth) effectively distinguish those that possess what Bourdieu ([1979] Citation2009, 177) calls “tastes of luxury” from those that rely on the “taste of necessity”. As TV chefs, then, the Novaks could be classified as “cultural intermediaries” par excellence, producers of TV programs that are “half-way between legitimate culture and mass production,” as Bourdieu (ibid.: 326) puts it, mediating between the two for large audiences. As arbitrators of culture, taste-making personalities like the Novaks presume to teach their aspiring middlebrow audiences how to “recognize the ‘guarantees of quality,’” of good food and cooking, and how to recognize fashionable and aspirational tastes and habits, and through their privileged position at the same time speak for the nation.

Who was their audience? In their large quantitative study of Slovene taste, Kamin, Tivadar and Koprivnik (Citation2012) report a correlation between respondents being interested in the Novaks’ cooking shows and having high economic, cultural and social capital. Classified in the study as “health conscious and socially responsible hedonists” these respondents, representing around 30% of the total, display some of the same concerns the show promotes: they are conscious of the effects food has on health and environment, and hence prioritize organic foods and meat-free diets. They also like to travel and generally enjoy eating out in countryside inns and urban activities such as going to the theater. They enjoy themselves through food, thus being an ideal audience for these shows. Alongside another group identified in this study as “urban adapted traditionalists” (almost 12%), who also enjoy food, although without much concern for its quality, and are more traditional in their values and less experimental when it comes to food, they together account for more than 40% of the sample and, at the same time, are also the highest earners of the society. This primary audience of their shows can explain the success of the Novaks’ mix of traditional fare and values with more exotic dishes as well as their ample references to classic literature and global tourist destinations, while at the same time embodying traditional, Catholic values that appeal to most (otherwise secular) Slovenes. In particular, they promote a particular type of (extended) family, where caring for children and being centered on family is crucial, normalizing further the hegemonic model of an “ordinary Slovene” family, its tastes and values (Meršak Citation2014, 78), even if in doing this, they also offer a more progressive version where cooking is not a strictly gendered activity. On the other side of the spectrum in terms of economic capital lies another group identified in this study (“aspirational traditionalists”, 27%), for whom food is seen as fuel. In this group, a strong correlation exists between eating meat and those cuisines with meat-centered dishes, such as those of former Yugoslavia (Kamin, Tivadar and Koprivnik Citation2012). This also possibly explains the intricate figuration of dish selection and presentation in the Novaks’ cooking: associated with the food habits of this low strata of the society, the food of the former Yugoslav countries lacks the culinary capital required to be considered aspirational for their shows’ audience.

3. Methodology

This article explores how the Novaks have worked to construct a national (and supra-national) identity through cookbooks, based on their popular TV series Love Through the Stomach. The cookbooks are entitled Sodobna družinska kuharija [Contemporary Family Cooking, 2009], Po zdravi pameti [According to Common Sense, 2010] and Preprosto slovensko [Simply Slovene, 2011]. These cookbooks, also referred to as celebrity cookbooks (Tominc Citation2017), are organized and written in line with contemporary cookbook writing trends, promoted by the spin-offs of international cooking stars, such as Jamie Oliver. People that appear in the cookbooks are synthetically personalized, dishes and ingredients are described using figurative and non-standardized language that reminds the reader of the chef’s brand, which their audience is familiar with from the TV screen. Books are organized in innovative ways reminding the reader of the brand built in the TV shows, and a long way from the prescribed traditional division into starters, meat dishes, vegetables and so on, common in more standard cookbooks (for a full analysis, cf. Tominc, Citation2017). For example, some sections have playful titles that evoke aspects of national culture (e.g. There is no lunch without soup) or popular sayings.

The analysis of the cookbook texts is based on analysis of contents and identification of discourse strategies (e.g. constructive strategies, strategies of transformation) they use, as defined in Critical Discourse Studies by Wodak et al. (Citation1999). In this, I focus on how actors/objects are linguistically referred to and described with the aim of demonstrating potential differences and similarities in construction of “us” (related to perceived Austrian cuisine dishes) and “them” (related to perceived Ottoman cuisine dishes). Their argumentation (in favour/against) is also analyzed to demonstrate how these group formations are justified discursively. To be able to do this, I selected and grouped the dishes from all three books according to the description given by the authors of the geographical/ethnic group they originated from. In the absence of this information, other common identification markers were used so that two groups of recipes could be created: “Austrian cuisine” dishes (including Wiener Schnitzel and palačinke analyzed in Section 4.1) and “Ottoman cuisine” dishes (including čevapčiči/ražnjiči and stuffed peppers/čufte analyzed in Section 4.2). The analysis of the dishes selected below demonstrates how the presentation of these dishes in cookbooks discursively constructs “our” common past positively only with one of these two groups, Austrian cuisine. It does this through making positive associations and storytelling that builds on recognized Slovene myths, legends and personalities from the time of the Empire, and through this justifies our European, rather than Balkan identity. Here, dishes are explicitly described as Austrian or Central European, whereas this is not the case for kebab-type dishes commonly associated in Slovenia with some former Yugoslav republics. These dishes are described vaguely as “Middle Eastern” or “Oriental”, rather than Serbian or Bosnian, and sometimes their origin is even completely obfuscated. The next section demonstrates how this distinction is created discursively through examples selected from each of the two groups analyzed.

4. How the Novaks present Slovenes and their cuisine in post-Socialism

4.1. Slovene cuisine and the prestige of “Central Europe”

As the Novaks weave dishes from across the world into their culinary repertoire, Austrian, Croatian and Hungarian culinary delicacies play a role, despite the otherwise rather side-lined place of these cuisines in the international culinary world.Footnote11 A positive representation of Austria is established through our shared past. This is most prominent in a section of their second book, According to Common Sense, dedicated to street food such as sausages, potato salad, and pickled gherkins that can be found in Vienna streets stalls. The section, entitled Kdor gre na Dunaj, naj pusti trebuh zunaj [Whoever goes to Vienna, let them leave their stomach outside of the city], is an old Slovene saying that probably refers to the unaffordability of food in Vienna at the time when people from the provinces frequently visited the Imperial Capital as the center of the Empire. The shared past and its associated cuisine are established via a brief introduction, in which the authors describe Vienna in terms of its most stereotypical characteristics (e.g. Strauss waltzes, cakes, palaces, coffee shops, Klimt, the big wheel in the Prater, and its Christmas markets), successfully incorporating references to the Habsburg past, when Slovene intellectuals from the provinces famously went to study or work in Vienna. The authors also mention Slovene influences in the capital, such as a house designed by the Slovene secessionist architect Plečnik, who worked across the Empire in Vienna and Prague, as well as in what is today the capital of Slovenia, Ljubljana (then known also in German as Laibach), where he designed some of the most important buildings. Further, they reference the oral folktale of Martin Krpan, a salt smuggler from a village in the Habsburg Duchy of Kranjska/Krain (today’s Slovenia), who fought the terrifying villain Brdavs to save the Emperor and who, after 1991, “became a ubiquitous national icon and an embodiment of the Slovenian character” (Baskar Citation2008). The Novaks represent this fictional literary character as part of “us,” a brave, loyal and down-to-earth nation, to whom the Emperor is grateful for saving the Empire.Footnote12 Nevertheless, the story also transports the modern day reader back to the days of the glorious Empire, the days when “we” were part of an important, respected and, most of all, European polity, thus feeding the sentiment of Austro-nostalgia that developed in Slovenia and other countries of the former Empire after independence in the 1990s as a reaction to the difficult economic, social and political realities in the successor countries (cf. Baskar Citation2007; Schlipphacke Citation2014; Bridges Citation2014; Hametz Citation2014). The two analyses presented below demonstrate how this association with Austria is established through the famous Austrian Wiener Schnitzel and pancakes (palačinke).

4.1.1. The case of Wiener Schnitzel

In Slovenia, Wiener Schnitzel is called dunajski zrezek [Viennese schnitzel, Dunaj being the Slovene name for Vienna].Footnote13 This veal schnitzel fried in breadcrumbs, considered the Austrian “national dish”, is commonly prepared in Slovenia (and elsewhere) with cheaper pork rather than veal. It is offered in restaurants with French fries, and is often the favorite dish, especially of those with less adventurous palates, positioned generally low on the economic and cultural capital scales. The Novaks refer to it as “Dunajc,” which is a less formal abbreviation for dunajski zrezek (Novak and Smej Novak 2009, 261). Probably eaten as commonly as the Balkan čufte, čevapčiči and stuffed peppers discussed in the next section, dunajski zrezek is an everyday part of the Slovene culinary repertory. However, unlike the Balkan dishes, the cookbooks describe it as more prestigious and traditional, linking it to the famous cultural symbols of Austria. They refer to it as the Austrian dish par excellence. In Austria it is “such an institution,” they say, “that it is even protected by law…The Viennese restaurant Figlmuller makes them with pork, but at the legendary Plachutta they are of course veal” (ibid.). It is difficult not to notice how Plachutta is designated as “legendary”, while in the continuation of the sentence the qualification of the schnitzel as “veal” suggests the communication of the (for the writer) obvious fact that veal, not pork, bears the higher culinary capital. In this case, the food “we” share with Austrians is openly assigned to the Austrians. Unlike the dishes that “we” share with the Balkans, the delicacies of the Empire are attributed location and, above all, tradition.

4.1.2. The case of palačinke

In their second book, According to Common Sense, in the section Mami, palačinke! [Mummy, pancakes!] they situate palačinke, the Slovene word (from Romanian, via Hungarian) for pancakes, amongst recipes for various other types of pancakes, such as American thick pancakes, Russian buckwheat pancakes and French crêpes. The section positions the dish as a Central European food, which is presented as something “logical”:

We all know where Central Europe is, don’t we? The answer is logical: Central Europe is where palačinke are made. Therefore, neither pancakes, nor Pfannkuchen, nor crêpes, nor blini. Even though this is all the same šmorn.Footnote14 Well, in fact the same palačinke (Novak and Smej Novak, 2010, 173 – bold in original).

4.2. The ambivalence of Balkan food

Given the popularity of what I refer to as Balkan foods in Slovenia, that is, the food heritage of the Ottoman Empire in the Balkan peninsula, it should not be a surprise that the Novaks’ efforts to present themselves as ordinary, family cooks involve the inclusion of popular Balkan dishes in their repertoire. Favorite grill-based dishes include ražnjiči, small pieces of meat (sometimes with vegetables) grilled on a stick (also known in Greece as souvlaki) and čevapi/čevapčiči (minced meat kebabs) both grill-based dishes. Unlike the dishes with an Austrian pedigree presented above, there is no explicit positive contextualization of these dishes in their “glorious” Ottoman past, drawing on centuries long Arab-Persian tradition, neither are these dishes presented as part of Slovenia’s culinary heritage.

4.2.1. The case of čevapčiči and ražnjiči

The Novaks describe ražnjiči as a lighter form of the “popular čevapčiči”, in fact “čevapčiči on a stick.” To demonstrate their cultural knowledge, they even provide the potential etymology of the word čevap (“kebab … ćebab … čevap”) demonstrating what linguists call lenition, a softening from a stop (k) to a fricative (ć, č), which was supposed to have happened as the word “kebab”, originally Farsi, encountered Slavic dialects (via Turkish) within the Turkish Ottoman state. In the course of this discussion, however, the Novaks clearly situate this Bosnian/Serbian culinary form within the broader framework of “Middle Eastern” cuisine, rather than more locally. Via this journey from “k” through the “Serbian” “ć” to the Slovene “č”, the Novaks signal the transitory character of the dish as Serbian/Bosnian and Balkan, and indeed embrace its character as Middle Eastern, which carries a less charged association. This diverts attention from the closer, and more threatening, Balkans to the more distant and exotic “Orient,” the supposed homeland of kebabs. The invocation of the “Orient” when describing ražnjiči appears even more explicitly in other contexts where they are directly linked with oriental tastes, smells and flavors (Novak and Smej Novak 2009, 230): “In these Oriental-inspired ražnjiči, the taste of the sea and the fields is mixed,” they state in one place in their cookbooks. In another, they describe the seasoning in a čevap recipe as Oriental, that is, with cumin and coriander, though they also allow for a “minimalistic” seasoning, “with salt and pepper” (ibid., 285)—as they do it in Bosnia, Serbia or even, they could have added, as we do it in Slovenia. Even when ražnjiči are referred to with a more “Slovene” name—nabodala—in this case in a recipe for a lamb dish, they still instruct us to look toward the “Orient”: “The recipe below takes us to where they surely know how to serve lamb: to the Orient” (Novak and Smej Novak 2010, 340). The acceptability of the somewhat distant and elusive “Orient” and the avoidance of the Balkans might be a consequence of romanticizing the “Orient” in Saïd’s terms—as mystical, mysterious and sensual—while the Balkans remain too real, close and rather low-prestige. Unlike the Balkans, the mysterious “Orient” remains far away from the everyday experience of the majority of the population and thus is not laden with the prejudices and stereotypes of the nearby lands, peoples, and languages of the former Yugoslavia.Footnote15

4.2.2. The case of stuffed peppers and čufte

This reference to the “Orient” is just one of the strategies the Novaks use to mask these dishes’ link to Slovenia’s migrants from former Yugoslavia, instead presenting them as “old-fashioned” dishes of unknown or vague origin. Such recycling, a recontextualizing of foods from one context to another, is described by Heldke (Citation2013) as “culinary colonialism,” referring to ways in which Westerners like to cook and talk about various “exotic” dishes without recognizing the historic and social context in which these foods were initially developed. In the Novaks’ reinterpretation, when they present čufte [from kofta, through a lenition as above] these are the dishes that “our grandmothers,” who lived through the Yugoslav days, used to cook (Novak and Smej Novak 2010, 231). The Novaks’ project, as the reader learns, is in fact “a challenge to those stuffed peppers of your grandmother.” As they question if they really are “the best you have ever eaten”, they also suggest that a change in Slovene eating habits is overdue, away from the old-fashioned, everyday, “traditional” cooking of our socialist grandmas’ tastes (Novak and Smej Novak 2009, 14; cf. Tominc Citation2014b). Stuffed peppers, then, symbolize not only the cuisine readers already know, but, mostly, the cooking they know from their Yugoslav past. While such dishes are characterized as comfort food, good and homely fare, and children’s favorites, they are never designated as Slovene, perhaps suggesting a general awareness of their “foreign” or Balkan origin. In their last cookbook, however, tellingly named Simply Slovene—and nevertheless containing many exotic dishes—they, despite all, recognize the need for the inclusion of some “grandmother’s” dishes, such as stuffed peppers and čufte, which appear in the section “Retro fast food.” These “retro” čufte, they tell the reader, replaced the “extravagantly spiced meatballs” they regularly prepared, because of their children’s continuous demand for the kind of food “Granny makes.” (Novak and Smej Novak 2011, 11). In this way, they represent these dishes as not only coming from the Yugoslav past (i.e. retro), but also as appropriate food to be eaten by less demanding palates, such as children’s.

The idea of the Balkans and all of its connotations remains intrinsically linked with the country’s socialist past, when Slovenes were encouraged to think of the other Yugoslav peoples as their brothers. This idea was expressed most memorably in the well-known slogan of “Brotherhood and Unity.” Among ordinary Slovenes, the slogan was often ironically used in its Serbo-Croatian form “Bratstvo i jedinstvo” rather than in Slovene, as a small but notable cynicism through which they communicated disbelief in the idea of such “brotherhood” and perhaps, through the 1980s, in the Yugoslav project itself. Serbo-Croatian, a linguistic term for the artificially constructed language used in Yugoslavia, was also the official language of the Yugoslav state and, most notably, that of the army (Bugarski Citation2013).Footnote16 At the end of the 1980s, when Slovenia’s request for independence became imminent, the Yugoslav National Army or the JNA, as it was known, became a symbol of oppression, a feeling that escalated sharply in 1991 during the brief, ten-day Slovene war in which the Yugoslav army tried to prevent Slovenia from gaining independence. This highly political context, charged with hatred for everything ‘Balkan’, is the subtext for one of the Novaks’ recipes for “modern čufte.” For their forty-year-old and older readers, they say, the mere mention of čufte might remind them of an event in which čufte, the period of war, and the “violent” aggressor (the JNA), were linked. In the summer of 1988, the story goes, three journalists—among them the future politician and Prime Minister Janez Janša—and a second lieutenant in the JNA were arrested for betraying military secrets:

At the time, the military court excluded the public, as it violently established Serbo-Croatian as the language of the judicial process. The prisoners had no other choice than to go on a hunger strike. And when the accused interrupted the hunger strike, the P.R. representative of the court published a legendary message for the public: “Janša juče pojeo čufte.” (Novak and Smej Novak 2011, 229)

In the Novak recipe for “modern” čufte, however, they suggest that this incident was the first time that Valentina Novak, then fifteen years old, heard of this dish, as she reportedly asked her mother: “what are čufte?” (ibid.). No doubt their čufte recipe is modern in name only, rather than in its ingredients or preparation, but they emphasize that this dish was new to Valentina at that particular time. Here, an association that the recipe holds is that of the “Other,” by its connection to the JNA and through this, Slovenia’s struggle for independence. Yet paradoxically, the author transforms the term ćufta, with its Serbo-Croatian soft ć as it should have appeared in this supposedly Serbo-Croatian quote, into čufta with a Slovene hard č, hence domesticating and normalizing the name for this foreign (and Balkan) dish (Novak and Smej Novak 2011, 229).

In contrast to the way the Novaks define Balkan dishes as Oriental and “retro”, migrants have developed their own more positive depiction of displaced “Yugoslav” Ottoman cuisine which can be used to demonstrate an alternative representation of the cuisine. In The Cookbook of the Slovene Bosnians—the first Bosnian cookbook written in the Slovene language—Bosniak women from the Islamic community of Slovenia represent Bosnian cuisine in their own terms (Žensko združenje Zemzem, Citation2011). Namely they connect it not only with their Ottoman Balkan heritage, but also to Arabo-Persian civilization. The cookbook provides etymologies of various expressions in terms of their Turkish, Arab, or Persian origins, and explains the traditions of food preparation and consumption. It contains a large selection of dishes that are cooked in the homes of these first- or second-generation immigrant women. Apart from the already widely known Balkan dishes, the cookbook contains recipes for dishes that can be found in Bosnian or Serbian homes or ethnic restaurants in Slovenia, though these restaurants only rarely operate under a clear ethnic distinction. The cookbook presents burek as one of many existing filo pastry rolls, a distinction that is somewhat blurred in Slovenia where burek came to designate all rolls, regardless of the filling. It also includes different čorbe and soups, including the famous Bosanski lonec (Bosnian pot) and Begova čorba (Beg’s stew)Footnote17, as well as čufte, čevapčiči/čevapi, sarme, dolme, pilav, moussaka, various characteristic salads, a number of famous sweets (baklava, tulumba, tufahija, lokum, halva, etc.), compotes, and even drinks. However, this rich heritage has not inspired the Novaks to describe and contextualize these dishes in a more positive way. Instead, Balkan food remains a minority, and primarily Bosnian, cause, while the Novaks speak through their TV shows to a much larger audience.

5. Conclusion

This paper has demonstrated elite engagement in the construction of a national culinary identity through celebrity cooking in Slovenia in post-Socialism. Based on the spin-off cookbooks from the Novaks’ popular TV series Love through the Stomach the paper has discussed their complex navigation between various Slovene pasts. Through an analysis of selected dishes popular in Slovenia that represent Austrian and Ottoman culinary legacies, I show how the discourse around the history Slovenia shares with Austria (as part of the Habsburg Empire) is appropriated for the purposes of post-1991 national identity building. Through this, the Novaks’ establish a link between the Slovenes as a nation and their (rightful) place in (Central) Europe, claiming a common history. As they cook for the nation, they promote the taste of Slovenia’s elites as the cultural intermediaries in the dissemination of acceptable taste. Other dishes, commonly originating in other countries of former Yugoslavia and today also popular in Slovenia, such as various kebabs or sarme, on the other hand, are not contexualised through association to their Ottoman culinary heritage. They are represented instead with a vague reference to the Middle East or an overtly negative contexualisation to “our” shared past in Yugoslavia. Erasure of any reference of these dishes to the cuisines of former Yugoslavia becomes particularly obvious when contrasted with the self-representation of this cuisine by Slovene Bosnian women.

The role of elites in this kind of post-socialist identity building, noted also in other European contexts, is seminal. They construct, re-orientate and justify the reconfiguration of national identities through culinary texts, contributing to the understanding of everyday food texts as political texts. Through this, the paper demonstrates how such food texts operate at the intersection of social class and national culinary identity, seeing TV chefs not just as celebrities, but as cultural intermediaries of elite class taste that have the potential to reflect, construct and reinforce larger discourse shifts. As such shifts have been taking place in Slovenia since the 1980s, these cookbooks can be seen as part of a body of texts through which the Slovene political and media elites prepared the ground for Slovenia’s entry to the EU in 2004, distancing themselves from its Balkan neighbors and invoking its European essence, through which they continue to maintain the public consensus and support for EU membership.

Sources

Novak, Luka and Valentina Smej Novak. 2009. Ljubezen skozi želodec. Sodobna družinska kuharija [Love through the Stomach: Contemporary Family Cooking]. Ljubljana: VALE Novak.

Novak, Luka and Valentina Smej Novak. 2010. Ljubezen skozi želodec: Po zdravi pameti [Love through the Stomach: According to Common Sense]. Ljubljana: VALE Novak.

Novak, Luka and Valentina Smej Novak. 2011. Ljubezen skozi želodec: Preprosto slovensko [Love through the Stomach: Simply Slovene]. Ljubljana: Totaliteta.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Many colleagues read and commented on versions of this paper, including the four anonymous reviewers at Food & Foodways journal and its editor, Carole Counihan. All their recommendations importantly strengthened this article and the claims I make in it. I thank them all for their advice, time and expertise. I also thank John Heywood for his invaluable language advice and Petra Slavec for creating the map in Figure 1.

2 I refer to the Novaks as celebrity chefs here, following Hollows (Citation2022, 3), who suggests professional expertise may not be a prerequisite. Instead, the term “may unite people with significantly different levels of cooking expertise and fame” and whose “fame is the product of significant media presence”.

3 A similar turn to the past can be seen in present-day Turkey, where glorification of the Ottoman past has re-emerged in popular culture in recent decades, including through culinary representation, building an identity for the Turkish people that links them less to the republican secularism of the start of the 20th century, than to the glory of the Ottoman Empire (for this, cf. Karaosmanoglu Citation2009) and in Poland, where the process of selective reappropriation of the Austro-Hungarian past vs distancing from the Russian past is taking place (cf. Zarycki Citation2014).

4 There were more than ten languages spoken in Habsburg Empire overall, with German being its lingua franca.

5 Čorba is a form of thick soup; čevapčiči are finger-shaped rolls of minced meat, like a kebab without a stick; moussaka consist of layers of minced meat, potatoes and aubergines baked in the oven; and djuveč is a meat and vegetable stew baked in the oven. All the dishes are spelt as they commonly appear in Slovene, following Slovene orthographic rules.

6 Ironically, the popular Apfelstrudel demonstrates Ottoman culinary influences in Austrian Empire, since this is apple wrapped in filo pastry, which is used in the Balkans and in the Middle East for preparation of pittas and various types of sweets.

7 Ražnjiči are pieces of meat on a stick and pleskavice resemble burger meat, though they are much thinner and larger.

8 Sarme are made of minced meat and rice wrapped in cabbage and čufte are small balls of minced meat cooked in sauce (similar to koftas).

9 Todorova ([1997] 2009, 150) further explains that "[t]he Central Europe of the 1980s was by no means a new term but it was a new concept. It was not the resurrection of “Mitteleuropa”: that had been a German idea, Central Europe was an East European idea; “Mitteleuropa” had always Germany at its core, Central Europe excluded Germany."

10 16th Gourmand World CookBook Awards 2011 – Best Cookbook, Eastern Europe; Nomination for the National Victor Award for the Best Entertainment Show in 2011 and 2012. In 2011, the biggest Slovene culinary forum Kulinarična Slovenija, for example, contained forty-seven pages dedicated to discussion of the show (Meršak 2011, 7).

11 When formerly communist countries, such as Hungary or Russia, are mentioned in these cookbooks, their cuisine is clearly framed in terms of their pre-communist culinary heritage emphasizing their Imperial past. About Russia, for example, the Novaks include stories from classic Russian fiction and aristocratic characters from Tolstoy’s War and Peace, as well as suggesting expensive drinks such as champagne as a suitable accompaniment to meals (Tominc Citation2014a, 317).

12 Of course, it could be further argued that the Brdavs – the villain of the story – epitomize the threat of the “barbaric” Ottoman empire to the “civilized” Austrian empire – a threat that started from early in the 15th century on, when the Ottomans started regular attacks on Austrian Southern provinces that famously culminated in the Siege of Vienna in 1683.

13 Schnitzel and zrezek is a thin slice of meat. I will refer to it in this text with its German name since steak is generally cut thicker.

14 “It’s all the same šmorn” is a Slovene saying meaning it’s all the same. Šmorn (from Ger. Schmarrn) is a thick pancake that has been torn into pieces, also known as cesarski praženec (Emperor’s omelet), which was – allegedly – first prepared for the Austrian Emperor Franz Joseph from where it got this name. The saying derives from the understanding that any mixture of ingredients will turn out the same.

15 Todorova ([1997] 2009, 12-13, 258) further captures this dichotomy as she contrasts the geographically and historically “concrete” Balkans with an “Orient” of “intangible nature”, an “exotic and imaginary realm, the abode of legends, fairy tales and marvels,” an “escapist dream,” “a Utopia”.

16 After the collapse of Yugoslavia, the newly established states each established new standard languages, for example Croatian, Serbian, Bosnian and Montenegrin, often through a process of linguistic purification, the introduction and enforcement of various grammatical rules and pronunciations, designed to distinguish these mutually intelligible languages from one another (Bugarski Citation2013).

17 Beg is a Turkish male social title, previously applied to those with special lineages.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun. 1988. “How to Make a National Cuisine: Cookbooks in Contemporary India.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 30 (1): 3–24. doi: 10.1017/S0010417500015024.

- Ashley, Bob, Joanne Hollows, Steve Jones, and Ben Taylor. 2004. Food and Cultural Studies. London: Routledge.

- Bachorz, Agata, and Fabio Parasecoli. 2023. “Savoring Polishness: History and Tradition in Contemporary Polish Food Media.” East European Politics and Societies and Cultures 37 (1): 103–24. doi: 10.1177/08883254211063457.

- Bachorz, Agata. 2019. “Drzwi Otwarte i Życiowa Szansa: kreowanie Gastrocelebrytow w Programie MasterChef Polska” [Open Doors and a Life Chance: creating Gastro-Celebrities in the MasterChef Polska Program.] Kultura Popularna 1:95–108.

- Bajic-Hajdukovic, Ivana. 2013. “Food, Family, and Memory: Belgrade Mothers and Their Migrant Children.” Food and Foodways 21 (1): 46–65. doi: 10.1080/07409710.2013.764787.

- Bakić-Hayden, Milica, and Robert Hayden. 1992. “Orientalist Variations on the Theme “Balkans:” Symbolic Geography in Recent Yugoslav Cultural Politics.” Slavic Review 51 (1): 1–15. doi: 10.2307/2500258.

- Baldwin, James E. 2018. “European Relations with the Ottoman World.” In The European World 1500–1800. An Introduction to Early Modern History, edited by Beat Kümin. London: Routledge.

- Baron, Ilan Zvi, and Galia Press-Barnathan. 2021. “Foodways and Foodwashing: Israeli Cookbooks and the Politics of Culinary Zionism.” International Political Sociology 15 (3): 338–58. doi: 10.1093/ips/olab007.

- Baskar, Bojan. 2007. “Austronostalgia and Yugonostalgia in the Western Balkans.” In Europe and Its Other: Notes on the Balkans, edited by Božidar Jezernik, Rajko Muršič and Alenka Bartulović, 57–8. Ljubljana: EiK.

- Baskar, Bojan. 2008. “Martin Krpan Ali Habsburški Mit Kot Sodobni Slovenski Mit” [Martin Krpan or the Habsburg Myth as a Contemporary Slovene Myth.] Etnolog 18: 75–93.

- Bell, David, and Joanne Hollows. 2005. “Making Sense of Ordinary Lifestyle.” In Ordinary Lifestyles: Popular Media, Consumption and Taste, edited by David Bell and Joanne Hollows. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

- Bošković, Aleksandar. 2013. “Yugonostalgia and Yugoslav Cultural Memory: Lexicon of Yu Mythology.” Slavic Review 72 (1): 54–78. doi: 10.5612/slavicreview.72.1.0054.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. [1979] 2009. Distinction. A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. New York: Routledge.

- Bracewell, Wendy. 2012. “Eating up Yugoslavia. Cookbooks and Consumption in Socialist Yugoslavia.” In Communism Unwrapped: Consumption in Cold War Eastern Europe, edited by Paulina Bren and Mary Neuburger. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bridges, Emily. 2014. “Maria Theresa, ‘the Turk,’ and Habsburg Nostalgia.” Journal of Austrian Studies 47 (2): 17–36. doi: 10.1353/oas.2014.0024.

- Bugarski, Ranko. 2013. “What Happened to Serbo-Croatian.” In After Yugoslavia. The Cultural Spaces of a Vanished Land, edited by Radmila Gorup. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Cusack, Igor. 2014. “Cookery Books and Celebrity Chefs: Men’s Contributions to National Cuisines in Sub-Saharan Africa.” Food, Culture, and Society 17 (1): 65–80. doi: 10.2752/175174414X13828682779168.

- Črnič, Aleš. 2014. “Vegetarijanstvo in Razred” [Vegetarianism and Social Class.] Kultura in Razred, ed. Breda Luthar. Ljubljana, Fakulteta za družbene vede, 201–21.

- Dolenc, Danilo. 2007. “Priseljevanje v Slovenijo z Območja Nekdanje Jugoslavije po Drugi Svetovni Vojni” [Immigration to Slovenia from the Area of ex-Yugoslavia after the Second World War.]” In Priseljenci. Študije o Priseljevanju in Vključevanju v Slovensko Družbo, edited by Miran Komac, 79–85. Ljubljana: Inštitut za narodnostna vprašanja.

- Drndić, Daša. 2014. Trieste. Translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać. New York: Haughton Mifflin Harcourt.

- Ferguson, Kenan. 2020. Cookbook Politics. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press

- Fotiadis, Ruža, Vladimir Ivanović and Radina Vučetić, eds. 2019. Brotherhood and Unity at the Kitchen Table: Food in Socialist Yugoslavia. Zagreb: Srednja Evropa.

- Gaul, Anny. 2022. “From Kitchen Arabic to Recipes for Good Taste: Nation, Empire, and Race in Egyptian Cookbooks.” Global Food History 8 (1): 4–33. doi: 10.1080/20549547.2021.2012869.

- Hametz, M. 2014. “Presnitz in the Piazza: Habsburg Nostalgia in Trieste.” Journal of Austrian Studies 47 (2): 131–54. doi: 10.1353/oas.2014.0029.

- Heldke, Lisa. 2013. “Let’s Cook Thai: Recipes for Colonialism.” In Food and Culture: A Reader, edited by Carole Counihan and Penny van Esterik, 394–408. New York: Routledge.

- Helstosky, Carol. 2003. “Recipe for the Nation: reading Italian History through La Scienza in Cucina and La Cucina Futurista.” Food and Foodways 11 (2–3): 113–40. doi: 10.1080/07409710390242372.

- Hollows, Joanne. 2022. Celebrity Chefs, Food Media and the Politics of Eating. London: Bloomsbury.

- Jelača, Dijana, Kolanović Maša, and Lugarić Danijela. 2017. The Cultural Life of Capitalism in Yugoslavia. (Post)Socialism and Its Other. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Johnston, Josée, and Shyon Baumann. 2010. Foodies. Democracy and Distinction in the Gourmet Foodscape. New York: Routledge.

- Jung, Yuson. 2012. “Experiencing the ‘West’ through the ‘East’ in the Margins of Europe: Chinese Food Consumption Practices in Post-Socialist Bulgaria.” Food, Culture, Society 15 (4): 579–98.

- Kamin, Tanja, Blanka Tivadar, and Samo Koprivnik. 2012. “Kaj Imajo Skupnega Andy Warhol, Pekorino in Vasabi? Prehranski Vzorci v Ljubljani in Mariboru” [What Do Andy Warhol, Pecorino and Wasabi Have in Common? Food Practices in Ljubljana and Maribor].” Družboslovne Razprave 28 (71): 93–111.

- Karaosmanoglu, Defne. 2009. “Eating the past: Multiple Spaces, Multiple Times Performing ‘Ottomanness’ in Istanbul.” International Journal of Cultural Studies 12 (4): 339–58. doi: 10.1177/1367877909104242.

- Klumbyte, Neringa. 2010. “The Soviet Sausage Rennaissance.” American Anthropologist 112 (1): 22–37.

- Luthar, Breda. 2010. “Shame, Desire and Longing for the West: A Case Study of Consumption.” In Remembering Utopia. The Culture of Everyday Life in Socialist Yugoslavia, edited by Breda Luthar and Maruša Pušnik, 341–96. Washington DC: New Academia Publishing.

- Luthar, Breda. 2012. “Popularna Kultura in Razredne Distinkcije v Sloveniji: Simbolne Meje v Egalitarni Družbi” [Popular Culture and Class Distinctions in Slovenia: Symbolic Boundaries in an Egalitarian Society.] Družboslovne Razprave XXVIII, 71:13–37.

- Magocsi, Paul R. 2018. Historical Atlas of Central Europe. Third Revised and Expanded Edition. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Meršak, Kristina. 2014. “‘Po Zdravi Pameti’ Analiza Družbenospolnih, Razrednih in Nacionalnih Reprezentacij v Oddaji Ljubezen Skozi Želodec” [‘According to Common Sense’ Gender, Nationality and Class in Cooking Show Love through the Stomach.] Časopis za Kritiko Znanosti, Domišljijo in Novo Antropologijo: 42 (255): 78–86.

- Mlekuž, Jernej. 2007. “Burek, Nein Danke! the Story of an Immigrant Dish and a Nationalist Discourse.”In Historical and Cultural Perspectives on Slovenian Migration, edited by Marjan Drnovšek, 173–201. Ljubljana: ZRC Publishing.

- Öztürk, Y. 2021. “Geçmişten Günümüze Türk Mutfak Kültürü Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme” [An Evaluation of Turkish Culinary Culture from past to Present.] Journal of Social and Humanities Sciences Research 8 (67): 582–90.

- Parys, Nathalie. 2013. “Cooking up a Culinary Identity for Belgium. Gastrolinguistics in Two Belgian Cookbooks (19th Century).” Appetite 71:218–31. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2013.08.006.

- Patterson, Patrick Hyder. 2011. Bought and Sold: Living and Losing the Good Life in Socialist Yugoslavia Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Petrović, Tanja. 2009. Representations of the Western Balkans in Political and Media Discourses. Ljubljana. Mirovni institut.

- Petrović, Tanja, and Ana Hofman. 2017. “Rethinking Class in Socialist Yugoslavia: Labor, Body, and Moral Economy.” In The Cultural Life of Capitalism in Yugoslavia. (Post)Socialism and Its Other, edited by Dijana Jelača, Maša Kolanović, Danijela Lugarić, 61–80. Palgrave MacMillan.

- Larsen Hanne Pico, and Susanne Österlund-Pötzsch. 2012. “Ubuntu in Your Heart’. Ethnicity, Innovation and Playful Nostalgia in Three ‘New Cuisines’ by Chef Marcus Samuelsson.” Food, Culture & Society 15 (4): 623–42. doi: 10.2752/175174412X13414122382881.

- Wodak, Ruth, Rudolf de Cilia, Martin Reisigl, and Karin Leibhart. 1999. The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Samancı, Özge. 2011. “Pilaf and Bouchées: The Modernization of Official Banquets at the Ottoman Palace in the Nineteenth Century.” In Food, Power and Status at the European Courts after 1789, edited by Daniëlle De Vooght. London: Routledge.

- Schlipphacke, H. 2014. “The Temporalities of Habsburg Nostalgia.” Journal of Austrian Studies 47 (2): 1–16. doi: 10.1353/oas.2014.0023.

- Shectman, Stas. 2009. “A Celebration of Masterstvo: Professional Cooking, Culinary Art, and Cultural Production in Russia.” In Food and Everyday Life in the Post-Socialist World, edited by Melissa Caldwell. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Spaskovska, Ljubica. 2008. “Recommunaissance: On the Phenomenon of Communist Nostalgia in Slovenia and Poland.” Anthropological Journal of European Cultures 17 (1): 136–50. doi: 10.3167/ajec.2008.01701008.

- Šaver, Boštjan. 2005. Nazaj v Planinski Raj: Alpska Kultura Slovenstva in Mitologija Triglava [Back to the Alpine Paradise: Alpine Culture of Slovenianness and Mithology of the Triglav Mountain]. Ljubljana: FDV.

- Tivadar, Blanka, and Andreja Vezovnik. 2010. “Cooking in Socialist Slovenia: housewives on the Road from a Bright Future to an Idyllic past.” Remembering Utopia: The Culture of Everyday Life in Socialist Yugoslavia. Edited by Breda Luthar and Maša Pušnik, 379–405. Washington, DC: New Academia Publishing.

- Tivadar, Blanka. 2009. “Naša Žena Med Željo po Limonini Lupinici in Strahom Pred Njo: zdrava Prehrana v Socializmu” [Our Woman between Desiring and Fearing Lemon Peel: healthy Eating in Socialism.] Družboslovne Razprave 25 (61): 7–23.

- Todorova, Maria. 1997 [2009]. Imagining the Balkans. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Tominc, Ana. 2014a. “Tolstoy in a Recipe: Globalization and Cookbook Discourse in Postmodernity.” Nutrition and Food Science (Special Issue Gastronomy) 44 (4): 317.

- Tominc, Ana. 2014b. “Legitimising Amateur Celebrity Chefs’ Advice and the Discursive Transformation of the Slovene Culinary National Identity.” European Journal of Cultural Studies 17 (3): 316–37. doi: 10.1177/1367549413508743.

- Tominc, Ana. 2015. “Cooking on the Slovene National Television in Socialism: An Overview of Cooking Programme from 1960 to 1990.” Družboslovne Razprave XXXI (79): 27–44.

- Tominc, Ana. 2017. The Discursive Construction of Class and Lifestyle. Celebrity Chef Cookbooks in Post-Socialist Slovenia. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Tominc, Ana. 2022. “Chef Ivan Ivačič’s Contribution to Culinary Modernization in 1960s Yugoslavia (Slovenia) through TV Cooking Shows.” In Food and Cooking on Early Television in Europe: Impact on Postwar Foodways, edited by Ana Tominc. London: Routledge.

- Velikonja, Mitja. 2005. Evroza. Kritika Novega Evrocentrizma. Ljubljana: Mirovni institut.

- Velikonja, Mitja. 2009. “Lost in Transition: Nostalgia for Socialism in Post-Socialist Countries.” East European Politics and Societies: And Cultures 23 (4): 535–51. doi: 10.1177/0888325409345140.

- Vezovnik, Andreja, and Ana Tominc. 2019. “Potica, the Leavened Bread That Reinvented Slovenia.” In The Emergence of National Foods, edited by V. Congdon, A. Ichijo and R. Ranta. London: Bloomsbury.

- Vezovnik, Andreja. 2009. Diskurz [Discourse]. Ljubljana, Založba: FDV.

- Vezovnik, Andreja, and Tanja Kamin. 2016. “Constructing Class, Gender and Nationality in Socialism: A Multimodal Analysis of Food Advertisements in the Slovenian Magazine Našažena.” Teorija in Praksa 53 (6): 1327–1343.

- Vučetić, Radina. 2019. “McDonaldization of Yugoslavia/Serbia 1988–2008: Two Images of a Society (from Americanization to anti-Americanism)” In Brotherhood and Unity at the Kitchen Table: Food in Socialist Yugoslavia, edited by Ruža Fotiadis, Vladimir Ivanović and Radina Vučetić. Zagreb: Srednja Evropa.

- Zarycki, Tomasz. 2009. “The Power of the Intelligentsia: The Rywin Affair and the Challenge of Applying the Concept of Cultural Capital to Analyze Poland’s Elites.” Theory and Society 38 (6): 613–48. doi: 10.1007/s11186-009-9092-6.

- Zarycki, Tomasz. 2014. Ideologies of Eastness in Central and Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Zevnik, Luka, and Peter Stanković. 2011. “Culinary Practices in Nove Fužine: Food and Processes of Cultural Exchange in a Slovenian Multiethnic Neighbourhood.” Food, Culture and Society 14 (3): 353–74.

- Zorić, Vladimir. 2013. “Discordia Concors: Central Europe in Post-Yugoslav Discourses.” In After Yugoslavia. The Cultural Spaces of a Vanished Land, edited by Radmila Gorup, 88–114. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Žensko združenje Zemzem 2011. Kuharica Slovenskih Bosank. Izbor Receptov iz Tradicionalne Bosanske Kuhinje [The Cookbooks of the Slovene Bosnians. A Selection of Recipes from a Traditional Bosnian Cuisine] Ljubljana: Žensko združenje Zemzem.