Abstract

Policies implemented to control the COVID-19 (C19) pandemic have faced public resistance. We examined this issue via an experimental vignette study embedded in a May 2020 national (U.S.) survey conducted by YouGov. Specifically, we explore how the public perceived a local policymaker proposing a C19-related isolation policy, based on the policy’s invasiveness or its punitivity. We find that more intrusive and more punitive policies generally resulted in colder feelings towards, and harsher perceptions of, the policymaker. However, our results suggest that the main driver of public sentiment towards the policymaker was the invasiveness of the proposed policy, with the policy's punitivity being less impactful. We discuss these findings in relation to policymaking, policy support and compliance, and tradeoffs between informal/formal controls, and intrusive/punitive policies.

The COVID-19 (C19) pandemic has led to dramatic disruptions in daily routines across the globe. As of June 15, 2022, there have been over 533 million confirmed cases of C19 worldwide, resulting in over 6.3 million deaths (World Health Organization, Citation2022). In the United States, as of June 15, 2022, there have been over 85 million C19 cases, resulting in over a million confirmed deaths (New York Times, Citation2022). In response, federal, state, and local governments have implemented a wide variety of restrictions and regulations to mitigate the spread of C19. In some cases, these restrictions have meant relatively minor changes in routine (e.g. masking in public). In other cases, these restrictions have been more severe, such as lockdowns, gathering or travel restrictions for an entire area (e.g. Jose, Citation2021; Markos, Citation2021), or individual isolation or quarantine orders (see Centers for Disease Control (CDC), Citation2021; KULR-8, Citation2021). Penalties for violating these restrictions can include steep fines and even jail time (e.g. Burke, Citation2020; Cachero, Citation2020; Millman, Citation2021), in an attempt to promote public health through the threat of criminal penalties.

Unsurprisingly, the public has not had a uniformly positive reception to these restrictions. In the United States, public acceptance and compliance has varied widely across regional, political, and sociodemographic divisions. This has been evident in the mass “anti-lockdown,” “anti-mask,” and “anti-vaccination” protests that have occurred across the country (e.g. Crow & Walmeir, Citation2020; Loew, Citation2021; Nguyen, Citation2020). The reasons behind the variation in public views are complex and multifaceted, and can involve substantial misinformation and disinformation influences (Cuan-Baltazar et al., Citation2020; Krause et al., Citation2020; Romer & Jamieson, Citation2020).

How the public perceives these restrictions, and the policymakers proposing them, matters both for ensuring compliance with the restrictions and avoiding political repercussions. As research on procedural justice suggests, if members of the public perceive a restriction as being too harsh, they may see that restriction (or the person proposing it) as illegitimate, and be less likely to comply (Bottoms, Citation2002; Tyler, Citation2003; White & Fradella, Citation2020). Understanding public perceptions of government-initiated restrictions can assist policymakers in balancing between regulations that best protect public health and safety, while ensuring substantial buy-in from the public. It can also inform ways to increase legitimacy and trust in government institutions seeking to address public health crises, particularly when decisions involve targeting certain actions (e.g. breaking quarantine) for criminalization.

The present study addresses these issues by examining how members of the public perceive a local-level policymaker who is proposing a policy that would isolate individuals exposed to C19. Specifically, we conducted an experimental vignette study in May 2020 to explore whether the public support for, or the perceived harshness of, a local-level policymaker were connected to the proposed policy’s perceived invasiveness and punitiveness.

Prior Research

Existing research in both public health and criminology provides indications for how the public perceives policies and policymakers addressing both the current (C19) and prior health pandemics (e.g. swine flu [H1N1], avian flu [H1N5]). Specific to the questions in the current study, research suggests that intrusiveness and severity of the proposed policy responses can dramatically influence public support.

Policy Intrusiveness

Perceptions of intrusiveness are informed by research on procedural justice and the “quality of treatment” of the public by policymakers (Snacken, Citation2015). Specifically, perceiving policymakers as violating privacy or other personal rights with new legislation may reduce the approval of the policymaker, increase their perceived harshness, and possibly lead to reduced compliance rates (Fagan, Citation2008; Snacken, Citation2012; Solum, Citation2004; Tyler, Citation2003).

Law and policing scholars have recently extended the procedural justice model by drawing on legal socialization scholarship to describe how people draw limits around authorities’ right to exercise their power. This concept of “bounded authority” (Trinkner et al., Citation2018) extends the procedural justice model by moving beyond the perceived quality of the police-public interaction (e.g. fairness, justice) to consider the perception of whether the police or other legal authorities have the right to regulate that specific behavior in that specific space. In other words, public perception of legal authorities is shaped by the assessment of “what power is being exercised when and where” (Trinkner et al., Citation2018, p. 282). Importantly, the assessment is not based on whether the legal authorities are exercising their power as granted by the law, but whether their behavior falls within the limits or bounds of what is considered appropriate in a given arena (e.g. a public space, a private home, a place of worship). Trinkner and colleagues (2018) argue that the public values agency and freedom “from regulation of surveillance in their personal lives” (p. 282) and is likely to be more sensitive to restrictive policies that they perceive as intrusive and as an encroachment on their civil liberties.

Research on procedural justice and bounded authority has largely explored policing behaviors, either generally or in counterterrorism roles, but as Williamson et al. (Citation2022) point out, bounded authority concerns are likely to be particularly apparent at the intersection of policing and public health. Public perceptions of appropriate regulatory behavior by authorities are shaped by legal socialization, and few alive today, particularly in the United States, have experienced a pandemic as far-reaching and severe at C19 and the resulting exercise of public health power to enforce mask mandates, limit gathering and movement, and impose isolation or quarantine orders (Lovelace, Citation2021).

The public health powers exercised during the C19 pandemic have certainly limited individual agency and freedom in an effort to protect the public health. For example, some jurisdictions adopted various types of cellphone-based technology to track movement and enforce isolation or quarantine. In Turkey, it was mandatory for people infected with COVID-19 to install an app that tracked movements of people who were instructed to self-isolate. If they left their homes, they would receive a text warning and an automated phone call, with continued violations subject to jail time (Reuters, Citation2020). This suggests location tracking that was real-time and constant. Hong Kong, Taiwan, and India have enforced the use of similar “geofencing” apps (Hui, Citation2020; Singh, Citation2020). In addition to location tracking, some jurisdictions require the individual to appear on camera. For example, Poland mandated that everyone under quarantine use an app that would randomly send an alert that required the individual to take a “selfie” photograph. If individuals did not response to alerts, police would check on them at home (Singh et al., Citation2020). Australia’s two largest states trialed apps that used facial recognition software to confirm user identity (Walsh, Citation2021). Based on the criteria discussed in Koops et al. (Citation2018) analysis of evolving legal perspectives on location tracking, the extension of location tracking into private homes, the continuity and frequency of observation (through geofencing and required check-ins), the active generation of data, and the use of these surveillance techniques on persons not committed of a crime suggests that use of this technology constitutes a serious intrusion of privacy.

However, whether the public perceives this as an intolerable intrusion is unclear. The intrusion of location tracking into the private domain may be more likely to trigger bounded authority concerns, which are context-specific (Trinkner et al., Citation2018). That is, is being tracked by your cellphone more or less intrusive than, for example, having to pass through a police checkpoint on a public road? On one hand, recent public opinion polls suggest that a majority of surveyed U.S adults feel that it’s not possible to go through daily life without the government or private companies collecting data about them (Auxier et al., Citation2019), which may suggest a certain numbness to “tireless and absolute surveillance” (Koops et al., Citation2018). On the other hand, respondents also felt that they have a lack of control over data collected out them, that this data collection is risky, and that they are concerned about how their data are used. For example, recent reporting suggests that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention purchased cellphone location data from a private vendor to track compliance with lockdown orders and vaccination efforts (Cox, Citation2022).

Tyler and Trinkner (Citation2017) argue that authorities can be rejected if they insist on trying to control behavior outside of appropriate domains. Bounded authority concerns are linked to perceptions of legitimacy of the police (Huq et al., Citation2017) and the broader legal system (Trinkner et al., Citation2018). Additionally, bounded authority concerns and perceptions of legitimacy are associated with public endorsement of the obligation to obey authorities (Huq et al., Citation2017; Trinkner et al., Citation2018), which predicts compliance with pandemic restrictions (Murphy et al., Citation2020; Van Rooij et al., Citation2020). In their study of Australian adults during the C19 pandemic, Williamson et al. (Citation2022) found that participants’ opposition to police surveillance strongly predicted both their bounded authority concerns and their perceived duty to obey.

As Trinkner and colleagues (2018) indicate, repeated police intrusion into peoples’ lives lowers not only police legitimacy, but the perceived legitimacy of the broader legal system. Regardless of authorities’ legal right to enforce public health law, what seems to matter more is whether that power is perceived by the public as intrusive and outside the normative considerations of appropriate regulatory action. To date, research has largely explored the impact on police legitimacy, but police are merely enforcing the restrictions imposed by policymakers. In the same way that enforcing a policy seen as a privacy intrusion can damage public perceptions of police, it may similarly damage perceptions of the policymaker(s) who implemented the policy itself.

This leads to our first two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: Individuals will perceive a policymaker proposing a more intrusive C19 policy with cooler feelings, compared to one proposing a less intrusive policy.

Hypothesis 2: Individuals will perceive a policymaker proposing a more intrusive C19 policy as being harsher, compared to one proposing a less intrusive policy.

Policy Punitivity

The relationship between public opinion and punitive policies is complex (Frost, Citation2010; Pickett, Citation2019; Ramirez, Citation2013). It’s unclear whether policymakers create punitive policies to follow public sentiment that favors harsh punishments, or instead their policies provide the cues that shape public sentiment itself. This difference determines whether a punitive society is constructed bottom-up, being led by public sentiment, or top-down, being led by the political interests of the elite.

One bottom-up perspective is the “democracy-at-work” thesis, which has been supported by studies linking crime rates, public opinion, and incarceration rates (e.g. Enns, Citation2016; Jennings et al., Citation2017). This approach argues that there is a demonstrated feedback process between perceptions of crime, public opinion, and public policy, such that the construction of a “crime problem” and concern about social disorder drive public punitiveness, which then shapes public policy. In support of this, survey research finds that individuals who believe crime is either increasing or getting worse are generally more supportive of punitive crime control measures (Brown & Socia, Citation2017; Pickett & Baker, Citation2014; Unnever & Cullen, Citation2010).Footnote1 This is also supported by Silver and Silver’s (Citation2017) work, which posits that group-oriented moral concerns (e.g. concern about crime as a threat to the in-group, authority, and purity) are associated with more punitive attitudes. Other research finds that fear of crime predicts support for punitive measures (e.g. Applegate et al., Citation2002; Chiricos et al., Citation2004; Costelloe et al., Citation2009; Unnever et al., Citation2007), and this may extend to supporting intrusive or punitive policies in the name of public safety (see Garland, Citation2001; Pickett et al., Citation2013).

Other research instead supports a top-down perceptive. That is, though there is evidence that the American public is particularly punitive toward people who break the law (Enns, Citation2016), research suggests that policymakers may overestimate this punitiveness (Cullen et al., Citation2000; Gottschalk, Citation2006; Roberts & Stalans, Citation2018) and that public opinion does not hold great influence over criminal justice policy (Brown, Citation2006; Matthews, Citation2005). The role of public opinion in policy punitiveness may be “mushy” (Cullen et al., Citation2000) or even a “myth” (Brown, Citation2006). In Making Crime Pay (1999), Beckett argues that increasingly punitive criminal justice policies are a form of top-down “elite manipulation,” whereby the public is manipulated (often through the media) into believing that crime is a serious social problem and that increasingly punitive interventions are the appropriate response. This perspective is supported by evidence that elite cues played an important role in early C19 response (Bisbee & Lee, Citation2022; Gollust et al., Citation2020; Grossman et al., Citation2020).

Evidence also suggests that punitive attitudes are not directly driven by fear of crime, but rather broader factors like education and political ideology (e.g. King & Maruna, Citation2009; King & Wheelock, Citation2007; Kleck & Jackson, Citation2017; Leverentz, Citation2011). In discussing elite manipulation and punitive public opinion, Beckett (Citation1999) points to the resonance between conservative ideology and an emphasis on individualism and individual responsibility, which is thought to underpin punitive attitudes towards “criminals.” In the case of the C19 pandemic, it is not clear that the public would see those who violate public health restrictions as “criminal,” and in fact they may see public health restrictions as an intolerable infringement on their own personal freedom. In this case, the public (or specific segments of it) may not be as supportive of punitive policies, especially considering the partisan gap in attitudes about the severity of the pandemic and the acceptability of public health restrictions (e.g. Allcott, Citation2020; Conway et al., Citation2021). Policymakers who are counting on punitive public sentiment toward lawbreakers may overestimate this sentiment (Cullen et al., Citation2000), especially in the context of the C19 pandemic.

Trinkner and colleagues (2018) argue that heavy-handed enforcement of sanction-based measures may provoke public resentment and backlash toward authorities (see Persak, Citation2019). This is especially true if the use of these sanctions is also perceived as a violation of bounded authority. Perceiving a punishment as disproportionate to the severity of the act (whether too punitive or too lenient) can reduce the perceived legitimacy of both the policy and the policymaker (see Fagan, Citation2008). For example, police and school officials in Logan, Ohio faced intense public backlash after the release of a video of an officer tasering a woman who refused to wear a mask at a middle school football game (Elfrink, Citation2020). The implication here is the police response (tasering) was perceived as overly punitive compared to the perceived severity of the transgression (refusing to wear a mask in a public setting), thus damaging the legitimacy of the police, school officials, and potentially of the broader legal system. In the context of the current pandemic, Williamson et al. (Citation2022) found that adult Australians were more likely to perceive a bounded authority violation when police were deemed “heavy-handed” when enforcing C19 restrictions.

In terms of the current study, we might expect that a proposed C19 policy with harsher punishments would not only lead to increased perceptions of a policymaker being “too harsh,” but also result in cooler feelings towards that policymaker. This leads to our next two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 3: Individuals will perceive a policymaker proposing a more punitive C19 policy with cooler feelings, compared to one proposing a less punitive policy.

Hypothesis 4: Individuals will perceive a policymaker proposing a more punitive C19 policy as being harsher, compared to one proposing a less punitive policy.

The Present Study

To test these hypotheses, we designed an experimental vignette study, conducted in May 2020, that provided several scenarios in which a local policymaker proposed a C19 policy that would isolate individuals exposed to the disease. The experimental vignette design allowed us to explore whether public perceptions about the local-level elected official proposing the policy were connected, as expected, to the proposed policy’s intrusiveness and/or the severity of the proposed punishment for violators. As such, our study explored two distinct research questions:

Research Questions

Does the intrusiveness of the method used to track violators of a proposed C19 policy influence respondents’ support for or the perceived harshness of the policy proposer?

Does the level of punishment given to violators of a proposed C19 policy influence respondents’ support for or perceived harshness of the policy proposer?

Research Design

Our study was embedded in a national online survey conducted by YouGov. The survey was fielded early in the C19 pandemic, with data collected between May 21st and May 26th, 2020. As noted by others (e.g. Harris & Socia, Citation2016; Socia et al., Citation2021), YouGov utilizes a two-stage sampling process, whereby surveys are first administered to a nonprobability “over-sample” drawn from an opt-in internet panel, and then the initial sample is reduced to a representative final sample by algorithmically matching respondent characteristics to an established sampling frame (Rivers, Citation2006). YouGov surveys have been previously validated in election studies (e.g. Vavreck & Rivers, Citation2008), and utilized in U.S.-based polling conducted by media outlets (e.g. Cohn, Citation2014; YouGov, Citation2014), and social science opinion research (e.g. Pearson‐Merkowitz & Dyck, Citation2017; Rydberg et al., Citation2018; Socia & Harris, Citation2016). Graham et al. (Citation2021) note that matched opt-in panels like those used by YouGov can provide relational inferences that are more likely to generalize than those of unmatched samples such as Amazon Mechanical Turk (see also Kennedy et al., Citation2016; Thompson & Pickett, Citation2020).

Vignette Scenario

Our experiment randomly assigned respondents to one of five groups. Each group considered a unique vignette about a fictional policymaker, Jerry Whitman, who was implementing a plan to isolate individuals exposed to C19.Footnote2 All five groups were presented with the same introduction paragraph:

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

The comparison group did not receive any additional information beyond the initial paragraph above. The other four (experimental) groups received additional details about Whitman’s policy that presented a unique combination of tracking method and punishment.

The tracking method described how violators of an isolation order would be identified, either through less intrusive police checkpoints (Checkpoints), or through more intrusive cell phone global positioning system (GPS) tracking of all residents (GPS). These scenarios represent realistic methods of enforcing isolation orders, while still representing vastly different levels of privacy infringement.Footnote3 Among the four experimental groups, two groups were presented with the less intrusive tracking method of police checkpoints, and two were presented with the more intrusive cell phone GPS tracking.

The punishment described the penalty for violating an isolation order, either as a fine up to $1,000 (Fine), or as a misdemeanor violation that carries up to 30 days in jail (Jail). Like the tracking method, we believe these represent realistic punishments, as they have been used as actual C19-related sanctions (e.g. Georgieva et al., Citation2021; Murphy et al., Citation2020; White & Fradella, Citation2020), while still representing two very different levels of punitivity (see Koops et al., Citation2018). Among the four experimental groups, two were presented with the less punitive fine punishment, and two were presented with the more punitive jail punishment.

As such, each of the four experimental groups considered a unique combination of tracking method and punishment for the proposed policy. These policy details were presented in a paragraph immediately below the introduction paragraph, in the following format:

Jerry Whitman has proposed a [blanket of police checkpoints all over the city/system that uses cell phone data to track the precise location of every resident at all times] to ensure that people who have been ordered to isolate remain at home. Violators face a [fine of up to $1,000/misdemeanor violation that carries up to 30 days in jail].

Thus, our experimental design yielded five distinct groups of randomly assigned respondents, each considering a single unique set of details relating to Whitman’s proposed policy to isolate those exposed to the virus (see supplemental Appendix A). In experimental notation, the design followed a post-test only factorial design with a control group:

RXA0B0O1(No Details group: No follow-up information)

RXA1B1O1(Checkpoints + Fine: Police Checkpoints/up to $1,000 fine)

RXA1B2O1(Checkpoints + Jail: Police Checkpoints/up to 30 days in jail)

RXA2B1O1(GPS + Fine: Phone GPS Tracking/up to $1,000 fine)

RXA2B2O1(GPS + Jail: Phone GPS Tracking/up to 30 days in jail)

We opted to not include a pre-test to avoid potential threats to internal validity. Instead, we relied on the randomization process to yield groups with a similar set of initial opinions. As noted later, covariate balance tests suggest our five groups are demographically similar. Thus, any group differences in opinions should be due to the experimental manipulation itself.

Independent Variables

Policy Details

Our models incorporate a set of indicators that measure the type of policy being proposed by Whitman in the vignette, in terms of the combination of tracking method and punishment. As noted earlier, participants were randomly assigned to consider one of five different policies, with one policy containing no details, and four others involving a unique combination of the proposed tracking method (Checkpoints vs. GPS) and the proposed punishment (Fine vs. Jail). As shown in , this resulted in five unique policies: No Details, Checkpoints + Fine, Checkpoints + Jail, GPS + Fine, and GPS + Jail. In the models, the set of policy indicators are in comparison to the group who received no policy details.

Table 1. Policy groups, by tracking method and punishment.

Demographic Variables

While other individual respondent demographics were measured in the survey, these are not the focus of the present study, and the successful covariate balance check suggests they are evenly distributed across the experimental groups. However, as a robustness check, we included demographic controls in follow up models for each outcome. These controls include respondent gender (Male), race/ethnicity (White, Black, Hispanic, Other), age, education, and political ideology (measured on a 5-point scale from very liberal to very conservative, with higher values representing a more conservative ideology).

Dependent Variables

For the outcomes, we measured two opinions about Whitman that might be influenced by the details of his proposed C19 isolation plan. Following the vignette, we asked respondents first how they felt about Whitman, and then how harsh they felt Whitman was being with his proposed plan. We posit that both measures inform on different aspects of Whitman’s perceived legitimacy.

Feelings towards Whitman

Immediately after receiving the vignette, respondents were asked to rate their feelings about Jerry Whitman using a “feeling thermometer” (see Alwin, Citation1997; Bavel et al., Citation2020; Wilcox et al., Citation1989). The feeling thermometer uses a scale where 0 indicates very cold and negative feelings and 100 indicates very warm and positive feelings. Across the entire sample, the average feeling towards Whitman was 49.48 (SD = 34.02), indicating average feelings that were neither warm nor cold.

Feeling thermometers have extensive use in measuring how members of the public feel about politicians, organizations, and groups (Druckman et al., Citation2021; Kahn et al., Citation2017; Unnever & Cullen, Citation2010), including as a measure of legitimacy (Tyler, Citation2003; Tyler & Huo, Citation2002). As noted by Hetherington (Citation1998, p. 793 footnote 3), a feeling thermometer taps dimensions of approval and personal characteristics, as well as policy considerations. Further, Hetherington (Citation1998, p. 765 figure 3) theorizes that an individual’s position on a given issue (e.g. C19 isolation requirements), can influence feelings about policymakers addressing this issue, but may not directly influence the trust placed in the policymaker. As our vignette concerns an unknown local-level policymaker from another state, whose proposals would not directly influence the respondent, it seems unlikely that respondents would have a firm basis to estimate their “trust” in Whitman, compared to their “feelings” towards him.

Whitman’s Harshness

After respondents rated their feelings towards Whitman, they were then asked to rate how harsh or lenient they felt Whitman was being with respect to enforcing C19 restrictions with the proposed policy. Respondents could select their response from a 7-point Likert measure, where 1 indicated “Jerry Whitman is being too lenient,” and 7 indicated “Jerry Whitman is being too harsh.” Across the entire sample, the global average harshness rating was 4.96, indicating Whitman was being slightly too harsh with his policy.

Analytical Model

The primary focus of our study is in comparing the differences between each of the five policy groups (No Details; Checkpoints + Fine; Checkpoints + Jail; GPS + Fine; GPS + Jail) for each of the two outcome measures (Feelings and Harshness). Given both dependent variables are fairly normally distributed,Footnote4 we examined between-group differences using analysis of variance (ANOVA), and ordinary least squares (OLS) regression models with robust standard errors. For each of the outcome measures, in the first model we only consider the experimental effects, and in the second model we add respondent demographic controls as a robustness check for our experimental effects.

Results

Descriptive statistics for the sample of respondents are presented in .

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and select covariate balance across experimental conditions.

Covariate balance tests. We conducted covariate balance tests to determine whether the randomization procedure produced five comparable groups of respondents. These balance checks compare the distribution of each of several demographic covariates (e.g. gender, race, age, education, and political ideology) across the five randomly assigned vignette groups of respondents. As shown in , the covariate differences across the conditions were all statistically indistinguishable from zero, suggesting the randomization procedure produced statistically similar groups of respondents. As such, we assume that any statistically significant differences between the groups’ outcome measures are due to the influence of the experimental conditions themselves (i.e. the policy differences). As a check on this assumption, we consider a model for each outcome that includes these control variables as predictors.

Below, we examine the differences between our five groups for each outcome measure. We start by considering the influence of the experiment on feelings towards Whitman, followed by the influence on perceptions of Whitman’s harshness. For each outcome, we first consider the main effects of the tracking and punishment details independent of each other. We then consider their combined effects (as compared to the “no details” policy), and then include sociodemographic control variables as a robustness check. We present unweighted data considering Miratrix et al.’s (2018) recommendation that unweighted sample average treatment effects (SATE) estimates do not substantially differ from weighted estimates, and to avoid the loss of power due to weighting. Overall conclusions did not change when weights were applied, but applying weights tended to increase standard errors. These alternative weighted models are presented in the supplemental Appendix B.

Feelings towards Whitman

The first model in presents the main effects of the tracking and punishment details on respondents’ feelings towards Whitman. The overall model was significant at the .001 level, and variance inflation factors suggested multicollinearity was not a problem. As a reminder, these feelings were measured on a feelings thermometer that ranged from 0 to 100, with higher values indicating warmer feelings. As shown, compared to providing any details about the policy, respondents felt significantly warmer towards Whitman when no details were provided (+16.39 degrees, p < .001). Controlling for the type of punishment, compared to a policy involving police checkpoints, respondents felt significantly cooler towards Whitman when the policy involved GPS tracking (-8.85 degrees, p < .001). Controlling for the tracking method, compared to a policy involving fines, respondents did not feel significantly different towards Whitman when the policy involved jail (-1.36 degrees, p > .05). This suggests that when it comes to feelings towards Whitman, providing any details matters, as does the intrusiveness (tracking method), but the level of punishment does not significantly influence such feelings.

Table 3. Feelings towards Whitman and perceived punitivity of policy by plan details, main effects.

In the first two models in , we consider the interaction of the tracking and punishment details in predicting respondents’ feelings towards Whitman, with the comparison being a policy that provides no details. The first model presents only the results of the experimental manipulation, while the second model adds respondent demographics as a robustness check. Note that while the first model includes 2,127 respondents, due to missing data on the political ideology measure, the second model includes only 1,951 respondents. Both models were significant overall (p < .001), and variance inflation factors suggested multicollinearity was not a problem.

Table 4. Feelings towards Whitman and perceived punitivity of policy by plan details, interaction effects.

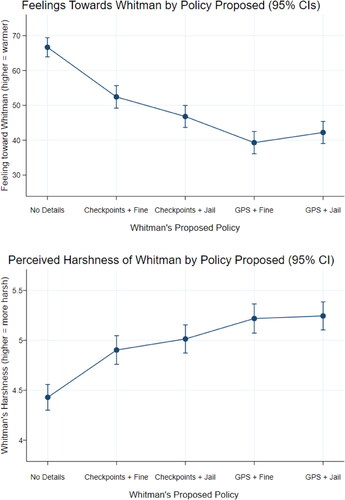

As shown in model 1, the constant indicates that respondents who received no details about Whitman’s policy felt an average of 66.68 degrees of warmth towards Whitman.Footnote5 In comparison, respondents in all four of the experimental groups who received policy details felt significantly colder towards Whitman: respondents presented with the Checkpoints + Fine policy felt 14.25 degrees cooler, respondents presented with the Checkpoints + Jail policy felt 19.87 degrees cooler, respondents presented with the GPS + Fine policy felt 27.38 degrees cooler, and respondents presented with the GPS + Jail policy felt 24.46 degrees cooler. A shared letter in the Group column indicates marginal estimates did not significantly differ between those policies (p > .05).

These results suggest that providing respondents with any details about the isolation policy meant colder feelings towards Whitman, which tends to support our first and third hypotheses. In further support of our first hypothesis, compared to police checkpoints, policies with the more intrusive GPS tracking yielded colder feelings towards Whitman. Interestingly, within each of the tracking method groups, the jail penalty yielded significantly colder feelings among the Checkpoints groups (-5.62 degrees; p = .02), but not within the GPS groups (+2.92 degrees; p = .20), as indicated by the shared “A” in the Group column. Thus, a more punitive punishment meant colder feelings towards Whitman only when paired with the less intrusive policy (police checkpoints), but not when paired with the more intrusive policy (GPS tracking). This yields only partial support for our third hypothesis.

In model 2, we include respondent demographics as a robustness check on the findings in model 1. As expected, overall conclusions about the different policies did not change in either direction or significance, and comparisons between the policies are consistent with the first model. While not the focus of the present study, results suggest that compared to women, men felt 5.28 degrees colder towards Whitman (p < .001). Compared to respondents who were White, respondents who were Black (+6.94; p < .01), Hispanic (+8.10; p < .001), or another race (+8.99; p < .001) felt warmer towards Whitman. Age did not influence feelings towards Whitman (p > .05). Compared to respondents with high school degrees or less, those with some college felt significantly cooler towards Whitman (-4.07; p < .05), while those with 4-year or post graduate degrees felt non-significantly cooler (p > .05 for both). Finally, every additional point more conservative in political ideology meant the respondent felt 8.38 degrees cooler towards Whitman (p < .001).

Whitman Harshness

The second model in presents the main effects of the tracking and punishment details on how harsh (or lenient) respondents felt Whitman was being in his response to C19.Footnote6 The overall model significant at the .001 level, and variance inflation factors suggested multicollinearity was not a problem. As shown, compared to providing any details about the policy, respondents felt Whitman was significantly less harsh (more lenient) when no details were provided (-.50, p < .001). Controlling for the type of punishment, compared to a policy involving police checkpoints, respondents felt Whitman was significantly harsher when the policy involved GPS tracking (.27, p < .001). Controlling for the tracking method, compared to a policy involving fines, respondents did not feel Whitman was significantly harsher when the policy involved jail (.07, p > .05). Similar to the models predicting feelings toward Whitman, this suggests that when it comes to Whitman’s perceived harshness, providing any details matters, as does the intrusiveness (tracking method), but the level of punishment does not significantly influence perceived harshness.

In the second set of models in , we consider the interaction of the tracking and punishment details in predicting how harsh (or lenient) respondents felt Whitman was being in his response to C19, with the comparison being a policy that provides no details. The first model presents only the results of the experimental manipulation (N = 2,127), while the second model adds the demographic control variables (N = 1,951). Both models were significant overall (p < .001), and variance inflation factors suggested multicollinearity was not a problem.

As shown in model 1, respondents in the comparison group, who received no details about Whitman’s isolation policy, rated Whitman’s harshness as 4.43 on average, which might be considered “slightly harsh.” In comparison, respondents in all four experimental groups who received policy details felt Whitman was significantly harsher (p < .001 for all). Specifically, respondents presented with the Checkpoints + Fine policy rated Whitman as .47 points harsher, respondents presented with the Checkpoints + Jail policy rated Whitman as .58 points harsher, respondents presented with the GPS + Fine policy rated Whitman as .79 points harsher, and those presented with the GPS + Jail policy rated Whitman as .82 points harsher.

Overall, these results suggest that compared to providing no details about the policy, providing any details meant respondents rated Whitman as harsher. This seems to support both our second and fourth hypotheses. Yet as shown in the Group column, while the more intrusive GPS policies yielded harsher perceptions compared to the Checkpoints policies (p < .05), within each type of tracking method, a more punitive punishment did not yield significantly harsher perceptions (p > .05). Thus, we find only mixed support for our fourth hypothesis, as harshness appears to be primarily driven by intrusiveness.

In model 2, we include respondent demographics as a robustness check on the findings in model 1. Again, as expected, overall conclusions about the different policies did not change in either direction or significance, and comparisons between the policies are consistent with the first model. In terms of respondent demographics, results suggest that compared to women, men felt Whitman was .33 points less harsh. Neither race/ethnicity nor age had significant effects (p > .05). Compared to respondents with high school degrees or less, those with some college or 4-year degrees felt Whitman was non-significantly harsher (p > .05 for both), while those with post graduate degrees felt Whitman was significantly harsher (.23; p < .05). Finally, every additional point more conservative in political ideology meant the respondent felt Whitman was .37 points harsher (p < .001).

graphically displays the impact of policy differences on each of the outcome measures for the models that exclude demographic variables. The top graph shows the feelings towards Whitman by policy, while the bottom graph shows the perceived harshness by policy. As can be seen, compared to the policy that provided no details, the policies that provided any details resulted in cooler feelings and increased perceived harshness, with the GPS policies yielding cooler feelings and increased perceived harshness compared to the Checkpoints policies.

Discussion

Using national-level survey data from early in the pandemic (May 2020), our study examined how public sentiment toward an imagined local-level elected official (Jerry Whitman), was influenced by details about Whitman’s proposed C19 isolation policy. We measured public sentiment toward Whitman in two ways: first as feelings of warmth towards Whitman, and second, as perceptions of Whitman’s harshness. We believe these together help inform on the amount of public approval Whitman would have in proposing C19-related policies.

We found that compared to providing no details about Whitman’s policy, providing any policy details led to more negative perceptions of Whitman (i.e. cooler feelings and increased perceived harshness). Further, the more intrusive policies (GPS tracking) resulted in more negative perceptions for Whitman compared to the less intrusive policies (police checkpoints), even when controlling for the level of punishment. However, after controlling for the tracking method (intrusiveness), an increased punishment (jail) meant colder feelings towards Whitman, but did not significantly influence perceived harshness.

Overall, our results tend to support prior research on public perceptions of appropriate policy responses. That is, a big driver of sentiment towards the policymaker was the intrusiveness of the proposed policy, and after controlling for this intrusiveness (checkpoints vs. GPS tracking), the level of punishment (fines vs. jail) was relatively less important. This suggests individuals may are more concerned with losing civil liberties (privacy) than they are of facing increased punishments for violations.

This stands in interesting comparison to Garland’s (Citation2001) “culture of control,” in which the general public is theorized to become more concerned with being protected from crime than with the threat of unrestrained state authority. That is, our results suggest that public sentiment toward those infected with C19 does not follow this same pattern of punitive sentiment, and instead, our survey respondents were more concerned about government intrusion. This may be because the public is more likely to identify with those who violate isolation orders (the analog of “criminals”), than with those at risk of becoming seriously ill from C19 (the analog of “crime victims”). Our respondents may also be more open to adopting individualized defensive tactics to protect themselves from infection (social distancing, masking), rather than relying on public policies to protect them (via imposing quarantines). Future research on punitive attitudes, crime, and public health should take care to distinguish between local, state, and national-level policies and policymakers, as public attitudes may vary as to what level of policy control is appropriate and desired from each level of government.

Policy Implications

Our research provides several policy implications concerning policymaking opportunities (“policy windows,” see Kingdon, Citation1995), policy support and compliance, and the tradeoffs between informal and formal controls, and intrusive or punitive policies. Garland (Citation2020) notes that American’s over-reliance on penal controls stems from the weakness of non-penal social controls. This would explain how the absence of effective social controls surrounding disease mitigation measures (e.g. informal mask requirements, recommended quarantine/isolation periods) may lead individuals to support penal controls to ensure compliance. This could also mean that perceived inefficacy of social controls, such as individuals not complying with masking requests or social distancing guidelines, may result in greater support for formal penal controls to force such behavior. For example, research has linked “nothing works” attitudes about crime and criminal justice to the “punitive era” in US crime policy (Phelps, Citation2011, p. 33). Perhaps the perception that some people will never voluntarily follow masking, social distancing, or other pandemic restrictions leads those concerned about C19 to both endorse punitive policies and increase their personal defensive routines. This has implications for, for example, extensive media coverage of anti-mask protests and profiles of C19 minimizers or deniers, which may promote a “nothing works” message even when a majority of the public supports mask-wearing (Balara, Citation2021; Murray, Citation2021; Talev, Citation2021). Future research might compare media coverage of crime and of the C19 pandemic in terms of influencing public perceptions of threat, punitive attitudes, and policy preferences.

Regarding the tradeoff between intrusion and punishment, Tyler (Citation2003) notes that decisions about compliance are more heavily weighted towards perceived certainty of punishment, rather than severity of punishment. If this is true, then policymakers seeking to gain compliance with C19 restrictions may want to focus on methods to increase certainty of punishment, such as using more intrusive tracking methods, rather than increasing the actual punishments. However, while proposing more intrusive tracking methods may increase compliance levels, our results suggest that it may also reduce support for the policy and/or the policymaker, at least compared to less intrusive methods (but see Aoki, Citation2021; Ross, Citation1982).

Limitations

Our study has several limitations to consider. First, our survey was fielded in May 2020, relatively early in the pandemic. As the pandemic continued, people may have changed (and continue to change) their feelings towards C19 restrictions and the pandemic itself. This may especially be the case for individuals who personally or vicariously experienced a C19 diagnosis (Cairney & Wellstead, Citation2021; Devine et al., Citation2021). Thus, a replication of this experiment may find different responses from a public who has dealt with the pandemic, and associated restrictions, for over two years.

Another limitation is that a vignette is obviously an artificial representation of reality, and thus respondents may perceive a “real” restriction differently than they would a hypothetical one (see Adriaenssen et al., Citation2020; Simonson, Citation2011). Further, we attempted to provide only enough details about Jerry Whitman to allow respondents to have a mental image of him, without inadvertently influencing their feelings towards him due to things unrelated to his proposed policy (e.g. his race, political party, religious beliefs, location of the city). However, this lack of detail may have also inflated the impact of the differences in the policies on respondents’ feelings. That is, it may be that respondents would be more forgiving of Whitman for proposing more intrusive or harsher policies were he from their “own” political party. Future research may want to explore how changing the policymaker’s demographics can influence public perceptions. Given the heavy politization of the C19 pandemic and responses to it (Camp et al., Citation2022; Gostin et al., Citation2020), changing the policymaker’s political party may be particularly impactful on public opinion, particularly in interaction with a respondent’s own political ideology.

In terms of our feeling thermometer, Li (Citation2021, p. 73) notes that “while the feeling thermometer is an easily interpreted measure of affect, with little ambiguity—warm indicates positive feelings and cold negative—the reality is often more complex.” While we contend that feelings of warmth towards a policymaker are an important measure of approval and support, we admit that even when this is combined with the measure of perceived harshness, we are not comprehensively measuring respondents’ perceptions of Whitman’s “legitimacy” or “approval.” Future research may want to measure the extent that feelings of warmth and/or harshness correlate with more direct questions policymaker legitimacy and/or approval (see Schoon, Citation2022).

Conclusion

Using a national vignette survey experiment, our study examined how Americans would perceive a local-level policymaker who was proposing C19 isolation policies, randomly varying the levels of intrusiveness (police checkpoints vs. phone GPS tracking) and punitiveness (fines vs. jail) for the proposed policy. Overall, we find that there is much overlap in what predicts respondents’ (cooler) feelings toward the policymaker, and what predicts respondents’ perceived harshness of the policymaker. This suggests that “feelings” and “harshness” may be tapping a similar underlying construct regarding perceptions of a policymaker. Specifically, our results suggest that even in the face of a worldwide pandemic that is seemingly in need of an effective policy response, perceptions of a policymaker may be harmed if a proposed policy is too intrusive or, in some cases, too punitive. In both crime and public health policy, policymakers must strike a delicate balance between precaution, punishment, and popularity. Our results shed light on a piece of the potential tradeoffs that inform on this balance.

Author’s Note

This research was supported by the Center for Public Opinion, the Office of the Dean of Fine Arts, Social Sciences, and Humanities, and the Office of the Provost at the University of Massachusetts Lowell. The authors would like to thank Dr. Jason Rydberg for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript. Please direct all questions and complements to the first author, and any and all complaints to the fourth author.

Notes

1 However, Kleck and Jackson (Citation2017, p. 1584) have questioned the generalizability of these findings, suggesting that “rather than being a response to real crime levels or actual exposure to crime, punitiveness is more likely to be a response to exposure to news media coverage of crime and a politically conservative context.”

2 We use the terms plan and policy interchangeably.

3 As noted earlier, both police checkpoints (Austen, Citation2021; Frost, Citation2021; Georgieva et al., Citation2021; Reuters, Citation2021) and cell phone GPS tracking (Garrett et al., Citation2021; Sabat et al., Citation2020; Singh, Citation2020) have been proposed or implemented to ensure isolation, quarantine, and lockdown compliance in multiple countries around the world. Koops and colleagues (2018) provides an excellent cross-national discussion of different types of privacy infringement by law enforcement.

4 Feelings had a Skewness of -.07 and a Kurtosis of 1.66, while the Harshness had a Skewness of -.21 and a Kurtosis of 2.54.

5 For readers less familiar with the Fahrenheit scale, 66.68 degrees is roughly room temperature in winter if you are responsible for paying the heating bill, or room temperature in summer if someone else is paying the air conditioner/electric bill.

6 While the outcome was measured using a 7-point Likert scale, a Brant test suggested the parallel regression assumption was not violated (χ2 = 29.10; p = .09), and thus an OLS regression model was suitable.

References

- Adriaenssen, A., Paoli, L., Karstedt, S., Visschers, J., Greenfield, V. A., & Pleysier, S. (2020). Public perceptions of the seriousness of crime: Weighing the harm and the wrong. European Journal of Criminology, 17(2), 127–150. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1477370818772768

- Allcott, H., Boxell, L., Conway, J., Gentzkow, M., Thaler, M., & Yang, D. (2020). Public health: Partisan differences in social distancing during the coronavirus pandemic. Journal of Public Economics, 191, 104254. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpubeco.2020.104254

- Alwin, D. F. (1997). Feeling thermometers versus 7-point scales: Which are better? Sociological Methods & Research, 25(3), 318–340. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124197025003003

- Aoki, N. (2021). Stay-at-home request or order? A study of the regulation of individual behavior during a pandemic crisis in Japan. International Journal of Public Administration, 44(11–12), 885–895. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2021.1912087

- Applegate, B. K., Cullen, F. T., & Fisher, B. S. (2002). Public views toward crime and correctional policies: Is there a gender gap? Journal of Criminal Justice, 30(2), 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0047-2352(01)00127-1

- Austen, I. (2021, April 16). A week of discouraging, frightening and frustrating pandemic developments. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/16/world/canada/coronavirus-cases-vaccines.html

- Auxier, B., Rainie, L., Anderson, M., Perrin, A., Kumar, M., Turner, E. (2019). Americans and privacy: Concerned, confused and feeling lack of control over their personal information. https://policycommons.net/artifacts/616499/americans-and-privacy/1597152/

- Balara, V. (2021, September 19). Fox news poll: Majorities favor mask and vaccine mandates as pandemic worries increase. Fox News. Retrieved March 1, from https://www.foxnews.com/official-polls/fox-news-poll-majorities-favor-mask-vaccine-mandates-as-pandemic-worries-increase

- Bavel, J. J. V., Baicker, K., Boggio, P. S., Capraro, V., Cichocka, A., Cikara, M., Crockett, M. J., Crum, A. J., Douglas, K. M., Druckman, J. N., Drury, J., Dube, O., Ellemers, N., Finkel, E. J., Fowler, J. H., Gelfand, M., Han, S., Haslam, S. A., Jetten, J., Kitayama, S., Mobbs, D., Napper, L. E., Packer, D.J., Pennycook, G. Peters, E., Petty, R. E., Rand, D. G., Reicher, S. D., Schnall, S., Shariff, A., Skitka, L. J., Smith, S. S., Sunstein, C. R., Tabri, N., Tucker, J. A., Linden, S. V. D., Lange, P. V., Weeden, K. A., Wohl, M. J. A., Zaki, J., Zion, S. R., & Willer, R. (2020). Using social and behavioural science to support covid-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour, 4(5), 460–471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z [InsertedFromOnline].

- Beckett, K. (1999). Making crime pay: Law and order in contemporary American politics. Oxford Univeristy Press.

- Bisbee, J., & Lee, D. D. I. (2022). Objective facts and elite cues: Partisan responses to covid-19. The Journal of Politics, 84(3), 1278–1000. https://doi.org/10.1086/716969

- Bottoms, A. (2002). Morality, crime, compliance, and public policy. In A. Bottoms & M. Tonry (Eds.), Ideology, crime and criminal justice (pp. 20–51) Willan Publishing.

- Brown, E. K. (2006). The dog that did not bark: Punitive social views and the ‘professional middle classes. Punishment & Society, 8(3), 287–312. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474506062101

- Brown, E. K., & Socia, K. M. (2017, December 1) Twenty-first century punitiveness: Social sources of punitive american views reconsidered [journal article]. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 33(4), 935–959. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-016-9319-4

- Burke, M. (2020). Coronavirus violations get maryland man sentenced to year in jail. NBC News (September 26). https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/coronavirus-violations-get-maryland-man-sentenced-year-jail-n1241182

- Cachero, P. (2020). Yes, you can face criminal charges, be fined, and even jailed for breaking a coronavirus quarantine. Insider. https://www.insider.com/breaking-coronavirus-quarantine-in-us-jail-charges-fines-2020-3

- Cairney, P., & Wellstead, A. (2021). Covid-19: Effective policymaking depends on trust in experts, politicians, and the public. Policy Design and Practice, 4(1), 1–14. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/25741292.2020.1837466

- Camp, S. L., Heath-Stout, L., Wooten, K., Barnes, J. A., Surface-Evans, S., Komara, Z., & Scott, A. R. (2022). Reflections on writing about health and well-being during the covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Historical Archaeology, 1–7.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, September 17). Legal authorities for isolation and quarantine. https://www.cdc.gov/quarantine/aboutlawsregulationsquarantineisolation.html

- Chiricos, T., Welch, K., & Gertz, M. (2004). Racial typification of crime and support for punitive measures. Criminology, 42(2), 358–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2004.tb00523.x

- Cohn, N. (2014). Explaining online panels and the 2014 midterms. The New York Times Company. Retrieved July 28, from http://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/28/upshot/explaining-online-panels-and-the-2014-midterms.html?smid=pl-share

- Conway, L. G., III, Woodard, S. R., Zubrod, A., & Chan, L. (2021). Why are conservatives less concerned about the coronavirus (covid-19) than liberals? Comparing political, experiential, and partisan messaging explanations. Personality and Individual Differences, 183, 111124.

- Costelloe, M. T., Chiricos, T., & Gertz, M. (2009). Punitive attitudes toward criminals: Exploring the relevance of crime salience and economic insecurity. Punishment & Society, 11(1), 25–49. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474508098131

- Cox, J. (2022, June 15). Cdc tracked millions of phones to see if Americans followed Covid lockdown orders. Vice, 2022. https://www.vice.com/en/article/m7vymn/cdc-tracked-phones-location-data-curfews

- Crow, D., Walmeir, P. (2020, April 22). Us anti-lockdown protests: ‘If you are paranoid about getting sick, just don’t go out’. Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/15ca3a5f-bc5c-44a3-99a8-c446f6f6881c

- Cuan-Baltazar, J. Y., Muñoz-Perez, M. J., Robledo-Vega, C., Pérez-Zepeda, M. F., & Soto-Vega, E. (2020). Misinformation of covid-19 on the internet: Infodemiology study. JMIR Public Health and Surveillance, 6(2), e18444. https://doi.org/10.2196/18444

- Cullen, F. T., Fisher, B. S., & Applegate, B. K. (2000). Public opinion about punishment and corrections. Crime and Justice, 27, 1–79. https://doi.org/10.1086/652198

- Devine, D., Gaskell, J., Jennings, W., & Stoker, G. (2021). Trust and the coronavirus pandemic: What are the consequences of and for trust? An early review of the literature. Political Studies Review, 19(2), 274–285. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1478929920948684

- Druckman, J. N., Klar, S., Krupnikov, Y., Levendusky, M., & Ryan, J. B. (2021). How affective polarization shapes americans’ political beliefs: A study of response to the covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 8(3), 223–234. https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.28

- Elfrink, T. (2020, September 28). A police officer tasered a maskless woman at a youth football game. Then, police and schools were flooded with threats. The Washington Post

- Enns, P. K. (2016). Incarceration nation. Cambridge University Press.

- Fagan, J. (2008). Legitimacy and criminal justice-introduction. Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 6, 123.

- Frost, N. (2021, August 21). The police set up checkpoints outside New zealand’s largest city. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2021/08/31/world/australia/new-zealand-covid-lockdown-checkpoints.html

- Frost, N. A. (2010). Beyond public opinion polls: Punitive public sentiment & criminal justice policy. Sociology Compass, 4(3), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9020.2009.00269.x

- Garland, D. (2001). The culture of control: Crime and social order in contemporary society. University of Chicago Press.

- Garland, D. (2020). Penal controls and social controls: Toward a theory of American penal exceptionalism. Punishment & Society, 22(3), 321–352. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474519881992

- Garrett, P. M., White, J. P., Lewandowsky, S., Kashima, Y., Perfors, A., Little, D. R., Geard, N., Mitchell, L., Tomko, M., & Dennis, S. (2021). The acceptability and uptake of smartphone tracking for covid-19 in Australia. PloS One, 16(1), e0244827.

- Georgieva, I., Lantta, T., Lickiewicz, J., Pekara, J., Wikman, S., Loseviča, M., Raveesh, B. N., Mihai, A., & Lepping, P. (2021). Perceived effectiveness, restrictiveness, and compliance with containment measures against the covid-19 pandemic: An international comparative study in 11 countries. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(7), 3806. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18073806

- Gollust, S. E., Nagler, R. H., & Fowler, E. F. (2020). The emergence of covid-19 in the US: A public health and political communication crisis. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 45(6), 967–981.

- Gostin, L. O., Cohen, I. G., & Koplan, J. P. (2020). Universal masking in the United States: The role of mandates, health education, and the CDC. JAMA, 324(9), 837–838. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.15271

- Gottschalk, M. (2006). The prison and the gallows: The politics of mass incarceration in America. Cambridge University Press.

- Graham, A., Pickett, J. T., & Cullen, F. T. (2021). Advantages of matched over unmatched opt-in samples for studying criminal justice attitudes: A research note. Crime & Delinquency, 67(12), 1962–1981. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128720977439

- Grossman, G., Kim, S., Rexer, J. M., & Thirumurthy, H. (2020). Political partisanship influences behavioral responses to governors’ recommendations for covid-19 prevention in the United States. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(39), 24144–24153. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2007835117

- Harris, A. J., & Socia, K. M. (2016). What’s in a name? Evaluating the effects of the “sex offender” label on public opinions and beliefs. Sexual Abuse : a Journal of Research and Treatment, 28(7), 660–678. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214564391

- Hetherington, M. J. (1998). The political relevance of political trust. American Political Science Review, 92(4), 791–808. https://doi.org/10.2307/2586304

- Hui, M. (2020, March 20). Hong Kong is using tracker wristbands to geofence people under coronavirus quarantine. Quartz. https://qz.com/1822215/hong-kong-uses-tracking-wristbands-for-coronavirus-quarantine/

- Huq, A. Z., Jackson, J., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Legitimating practices: Revisiting the predicates of police legitimacy. British Journal of Criminology, 57(5), 1101–1122.

- Jennings, W., Farrall, S., Gray, E., & Hay, C. (2017). Penal populism and the public thermostat: Crime, public punitiveness, and public policy. Governance, 30(3), 463–481. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/gove.12214

- Jose, R. (2021). September 26). Sydney's covid-19 lockdown to end sooner for the vaccinated. The Gazette. https://gazette.com/news/us-world/sydneys-covid-19-lockdown-to-end-sooner-for-the-vaccinated/article_b23fc86d-487e-5c73-bf3a-24e075cc6627.html

- Kahn, K. B., Thompson, M., & McMahon, J. M. (2017). Privileged protection? Effects of suspect race and mental illness status on public perceptions of police use of force. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 13(2), 171–191. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-016-9280-0

- Kennedy, C., Mercer, A., Keeter, S., Hatley, N., McGeeney, K., Gimenez, A. (2016). Evaluating online nonprobability surveys. https://www.pewresearch.org/methods/2016/05/02/evaluating-online-nonprobability-surveys/

- King, A., & Maruna, S. (2009). Is a conservative just a liberal who has been mugged? Punishment & Society, 11(2), 147–169. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474508101490

- King, R. D., & Wheelock, D. (2007). Group threat and social control: Race, perceptions of minorities and the desire to punish. Social Forces, 85(3), 1255–1280. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2007.0045

- Kingdon, J. W. (1995). Agendas, alternatives, and public policies (2nd ed.). Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc.

- Kleck, G., & Jackson, D. B. (2017). Does crime cause punitiveness? Crime & Delinquency, 63(12), 1572–1599. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716638503

- Koops, B.-J., Newell, B. C., & Skorvanek, I. (2018). Location tracking by police: The regulation of tireless and absolute surveillance. UC Irvine L. Rev, 9, 635.

- Krause, N. M., Freiling, I., Beets, B., & Brossard, D. (2020). Fact-checking as risk communication: The multi-layered risk of misinformation in times of covid-19. Journal of Risk Research, 23(7–8), 1052–1059. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/13669877.2020.1756385

- KULR-8. (2021, August 23). No quarantine after a positive covid-19 test could mean jail, fines for mississipp. KULR-8. https://www.kulr8.com/coronavirus/no-quarantine-after-a-positive-covid-19-test-could-mean-jail-fines-for-mississippi/article_fb8674f8-0450-11ec-bf11-6b4acd90ae5e.html

- Leverentz, A. (2011). Neighborhood context of attitudes toward crime and reentry. Punishment & Society, 13(1), 64–92. https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474510385629

- Li, X. (2021). More than meets the eye: Understanding perceptions of china beyond the favorable–unfavorable dichotomy. Studies in Comparative International Development, 56(1), 68–86. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-021-09320-1

- Loew, T. (2021, September 18). Demonstrators gather in Salem to protest covid-19 vaccine, mask mandates. Statesman Journal. https://www.statesmanjournal.com/story/news/2021/09/18/hundreds-gather-salem-protest-covid-19-vaccine-mask-mandates/8403429002/

- Lovelace, B. J. (2021, September 20). Covid is officially America’s deadliest pandemic as U.S. Fatalities surpass 1918 flu estimates. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/09/20/covid-is-americas-deadliest-pandemic-as-us-fatalities-near-1918-flu-estimates.html

- Markos, M. (2021, March 8). Life in lockdown: A timeline of the covid shutdown in Massachusetts. NBC Boston. https://www.nbcboston.com/life-in-lockdown/life-in-lockdown-a-timeline-of-the-covid-shutdown-in-massachusetts/2320541/

- Matthews, R. (2005). The myth of punitiveness. Theoretical Criminology, 9(2), 175–201. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362480605051639

- Millman, J. (2021). NYC fines up to $15k for covid violations in effect; NY hospitalizations highest since July 15. NBC New York. https://www.nbcnewyork.com/news/local/nyc-fines-of-up-to-15000-a-day-for-covid-rule-breakers-take-effect-friday/2660359/

- Miratrix, L. W., Sekhon, J. S., Theodoridis, A. G., & Campos, L. F. (2018). Worth weighting? How to think about and use weights in survey experiments. Political Analysis, 26(3), 275–291. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/pan.2018.1

- Murphy, K., Williamson, H., Sargeant, E., & McCarthy, M. (2020). Why people comply with covid-19 social distancing restrictions: Self-interest or duty? Australian & New Zealand Journal of Criminology, 53(4), 477–496. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004865820954484

- Murray, P. (2021). National: Majority back vaccine, mask mandates. Monmouth University Polling Institute. Retrieved March 1, from https://www.monmouth.edu/polling-institute/reports/monmouthpoll_us_091521/

- New York Times. (2022, June 15). Coronavirus in the U.S.: Latest map and case count. New York Times. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/us/covid-cases.html

- Nguyen, L. (2020). December 14). Orange county breaks 100,000 covid-19 cases as demonstrators protest to reopen businesses. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/socal/daily-pilot/news/story/2020-12-14/orange-county-breaks-100-000-covid-19-cases-as-demonstrators-protest-to-reopen-businesses

- Pearson‐Merkowitz, S., & Dyck, J. J. (2017). Crime and partisanship: How party id muddles reality, perception, and policy attitudes on crime and guns. Social Science Quarterly, 98(2), 443–454. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssqu.12417

- Persak, N. (2019). Beyond public punitiveness: The role of emotions in criminal law policy. International Journal of Law, Crime and Justice, 57, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijlcj.2019.02.001

- Phelps, M. S. (2011). Rehabilitation in the punitive era: The gap between rhetoric and reality in us prison programs. Law & Society Review, 45(1), 33–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2011.00427.x

- Pickett, J. T. (2019). Public opinion and criminal justice policy: Theory and research. Annual Review of Criminology, 2(1), 405–428. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-011518-024826

- Pickett, J. T., & Baker, T. (2014). The pragmatic American: Empirical reality or methodological artifact? Criminology, 52(2), 195–222. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12035

- Pickett, J. T., Mears, D. P., Stewart, E. A., & Gertz, M. (2013). Security at the expense of liberty: A test of predictions deriving from the culture of control thesis. Crime & Delinquency, 59(2), 214–242. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128712461612

- Ramirez, M. D. (2013). Punitive sentiment. Criminology, 51(2), 329–364. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9125.12007

- Reuters. (2020, April 8). Turkey to track citizens via mobile phones to enforce quarantines. Reuters. Retrieved June 15, from https://www.reuters.com/article/us-health-coronavirus-turkey-phones/turkey-to-track-citizens-via-mobile-phones-to-enforce-quarantines-idUSKBN21Q1ZY

- Reuters. (2021, August 15). Roadblocks erected in Sydney as Australia battles delta outbreak. CNBC. https://www.cnbc.com/2021/08/16/roadblocks-erected-in-sydney-as-australia-battles-delta-outbreak.html

- Rivers, D. (2006). Sample matching: Representative sampling from internet panels. Polimetrix White Paper Series

- Roberts, J. V., & Stalans, L. J. (2018). Public opinion, crime, and criminal justice. Routledge.

- Romer, D., & Jamieson, K. H. (2020). Conspiracy theories as barriers to controlling the spread of covid-19 in the US. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 263, 113356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.113356

- Ross, H. L. (1982). Deterring the drinking driver: Legal policy and social control. Lexington Books.

- Rydberg, J., Dum, C. P., & Socia, K. M. (2018, May 16) Nobody gives a #%&!: A factorial survey examining the effect of criminological evidence on opposition to sex offender residence restrictions. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 14(4) 541–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-018-9335-5

- Sabat, I., Neuman-Böhme, S., Varghese, N. E., Barros, P. P., Brouwer, W., van Exel, J., Schreyögg, J., & Stargardt, T. (2020). United but divided: Policy responses and people’s perceptions in the EU during the COVID-19 outbreak. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 124(9), 909–918.

- Schoon, E. W. (2022). Operationalizing legitimacy. American Sociological Review, 87(3), 478–503. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/00031224221081379

- Silver, J. R., & Silver, E. (2017). Why are conservatives more punitive than liberals? A moral foundations approach. Law and Human Behavior, 41(3), 258–272. Jun DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000232

- Simonson, J. (2011). Problems in measuring punitiveness–results from a German study. Punitivity. International Developments, 1, 73–96.

- Singh, H. J. L., Couch, D., & Yap, K. (2020). Mobile health apps that help with covid-19 management: Scoping review. JMIR Nursing, 3(1), e20596.

- Singh, V. (2020, April 3, 2020). Geo-fencing app will be used to locate quarantine violators. The Hindu. https://www.thehindu.com/news/national/coronavirus-geo-fencing-app-will-be-used-to-locate-quarantine-violators/article31241055.ece

- Snacken, S. (2012). Legitimacy of penal policies: Punishment between normative and empirical legitimacy. In Legitimacy and compliance in criminal justice (pp.59–79). Routledge.

- Snacken, S. (2015). Punishment, legitimate policies and values: Penal moderation, dignity and human rights. Punishment & Society, 17(3), 397–423. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/1462474515590895

- Socia, K. M., & Harris, A. J. (2016). Evaluating public perceptions of the risk presented by registered sex offenders: Evidence of crime control theater? Psychology, Public Policy, & Law, 22(4), 375–385. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000081

- Socia, K. M., Rydberg, J., & Dum, C. P. (2021). Punitive attitudes toward individuals convicted of sex offenses: A vignette study. Justice Quarterly, 38(6), 1262–1289. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1080/07418825.2019.1683218

- Solum, L. B. (2004). Procedural justice. Southern California Law Review, 78(1), 181–321.

- Talev, M. (2021). August 17). Axios-ipsos poll: Most Americans favor mandates. Retrieved March 3 from https://www.axios.com/axios-ipsos-poll-mandates-masks-vaccinations-f0f105a7-3c2e-4953-aac9-f25516128b11.html

- Thompson, A. J., & Pickett, J. T. (2020). Are relational inferences from crowdsourced and opt-in samples generalizable? Comparing criminal justice attitudes in the gss and five online samples. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 36(4), 907–932. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-019-09436-7

- Trinkner, R., Jackson, J., & Tyler, T. R. (2018). Bounded authority: Expanding “appropriate” police behavior beyond procedural justice. Law and Human Behavior, 42(3), 280–293.

- Tyler, T. R. (2003). Procedural justice, legitimacy, and the effective rule of law. Crime and Justice, 30, 283–357. https://doi.org/10.1086/652233

- Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the law: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Russell Sage Foundation.

- Tyler, T. R., & Trinkner, R. (2017). Why children follow rules: Legal socialization and the development of legitimacy. Oxford University Press.

- Unnever, J. D., & Cullen, F. T. (2010). The social sources of american's punitiveness: A test of three competing models. Criminology, 48(1), 99–129. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2010.00181.x

- Unnever, J. D., Cullen, F. T., & Fisher, B. S. (2007). “ A liberal is someone who has not been mugged”: Criminal victimization and political beliefs. Justice Quarterly, 24(2), 309–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820701294862

- Van Rooij, B., de Bruijn, A. L., Reinders Folmer, C., Kooistra, E. B., Kuiper, M. E., Brownlee, M., Olthuis, E., Fine, A. (2020). Compliance with covid-19 mitigation measures in the United States. Amsterdam law school research paper (2020–21).

- Vavreck, L., & Rivers, D. (2008). The 2006 cooperative congressional election study. Journal of Elections, Public Opinion and Parties, 18(4), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/17457280802305177

- Walsh, T. (2021, September 9). I'd prefer an ankle tag: Why home quarantine apps are a bad idea. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/id-prefer-an-ankle-tag-why-home-quarantine-apps-are-a-bad-idea-167533

- White, M. D., & Fradella, H. F. (2020). Policing a pandemic: Stay-at-home orders and what they mean for the police. American Journal of Criminal Justice : AJCJ, 45(4), 702–717.

- Wilcox, C., Sigelman, L., & Cook, E. (1989). Some like it hot: Individual differences in responses to group feeling thermometers. Public Opinion Quarterly, 53(2), 246–257. https://doi.org/10.1086/269505

- Williamson, H., Murphy, K., Sargeant, E., & McCarthy, M. (2022). The role of bounded-authority concerns in shaping citizens' duty to obey authorities during covid-19. Policing: An International Journal, 45(2), 169–185. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-03-2022-0036

- World Health Organization. (2022). Weekly epidemiological update on covid-19 – 15 June 2022. W. H. Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/weekly-epidemiological-update-on-covid-19–-15-june-2022

- YouGov. (2014). Latest findings in economist/yougov poll. http://today.yougov.com/news/categories/economist/

APPENDIX A.

Vignette SCENARIOS

“No Details” Group

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

Checkpoints + Fine Group

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

Jerry Whitman has proposed a blanket of police checkpoints all over the city to ensure that people who have been ordered to isolate remain at home. Violators face a fine of up to $1,000.

Checkpoints + Jail Group

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

Jerry Whitman has proposed a blanket of police checkpoints all over the city to ensure that people who have been ordered to isolate remain at home. Violators face a misdemeanor violation that carries up to 30 days in jail.

GPS + Fine Group

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

Jerry Whitman has proposed a system that uses cell phone data to track the precise location of every resident at all times to ensure that people who have been ordered to isolate remain at home. Violators face a fine of up to $1,000.

GPS + Jail Group

Jerry Whitman is a mayor in a small city in another state. He is 40, married with two children in school, and prior to becoming mayor, served two terms on the city council. Like local officials all over the country, he is trying to keep his city safe from COVID-19. To do that, he is implementing a plan to isolate everyone who has been exposed to the virus.

Jerry Whitman has proposed a system that uses cell phone data to track the precise location of every resident at all times to ensure that people who have been ordered to isolate remain at home. Violators face a misdemeanor violation that carries up to 30 days in jail.