Abstract

Satisfaction from police performance in cases that are screened out from police investigation is low, particularly for victims who report online. In a randomized controlled trial, we report the impact of reassurance telephone callbacks on satisfaction scores for victims of vehicle crime in London, United Kingdom. Evidence suggests that reassurance callbacks cause victims to express more favorable attitudes toward the police, with more pronounced satisfaction scores among minority victims, particularly those who report their crime online. We argue that callbacks to victims are advantageous in an era of a police legitimacy crisis with diminished resources for law enforcement.

Law enforcement and the wider criminal justice system treat crime as an infraction against society rather than individuals. As such, victim engagement and participation in the criminal justice process is diminished, resulting in poor rates of victim satisfaction and a policing approach which some view as so poor to be deemed as “secondary victimization” (see Hodgkinson et al., Citation2020; Orth, Citation2002). Although recognition of victims’ rights emerged more than 50 years ago (Joffee, Citation2009), legal instruments have not translated into a formidable “victim-centric” approach (Lay, Ariel, & Harinam, (in press)). Consequently, an overall rating of victims’ experience with the police remains a challenge.

A lack of timely and accurate information on investigations is one of the most significant drivers of victim dissatisfaction (HM Inspectorate of Constabulary, 2014; MOPAC, Citation2021; Victim Support Report, Citation2011). For example, the 2012 Crime Survey for England and Wales found that 19% of victims desired support, information, and advice more than anything else, but such data were received in only 9% of cases (Freeman, Citation2013). Moreover, technological advancements that aim to make policing more cost-efficient have not improved victim satisfaction. Since April 2020, a Telephone and Digital Investigation Unit survey has been used to assess the satisfaction of victims reporting crime over the telephone and online to the London Metropolitan Police Service (the Met). The survey found that victim satisfaction across all reporting methods has seen a significant decline from 2019 to 2021 and online reporting generated low satisfaction compared to reporting by telephone (MOPAC, Citation2021). Overall, electronic reporting yielded an overall satisfaction rate of 56% (MOPAC, 2019, p. 7).

These negative sentiments are understandable, particularly in screened-out cases. While all crimes are registered by the police (though not all reports to the police are), the majority will be terminated following initial inquiries due to the absence of solvability factors (Coupe et al. Citation2019), public interest, or crime control policies. As such, for many victims, the only police response they will receive is an emailed or texted “victim letter,” which provides a crime reference number, advice on crime prevention, and victim support. With limited opportunity to increase detection rates, if the police wish to increase the satisfaction of victims, they must therefore change the process of “letting victims down” (Clark et al., in press).

Research consistently shows that people reporting a crime to the police are often more interested in how they are treated by the criminal justice system rather than the arrest of the offender (Jonathan-Zamir & Harpaz, Citation2018). Victims are sufficiently rational to understand the need to prioritize police resources (Victim Support Survey 2011); nevertheless, they expect to be treated fairly and courteously no matter the case outcome (MOPAC, Citation2021). Therefore, what matters most in police–public encounters is how police engage with victims rather than a tangible criminal justice outcome—the opposite of what police officers tend to think (Bates et al., Citation2015; Jonathan-Zamir & Harpaz, Citation2014).

Victims are concerned about tenets of procedural justice, such as fair treatment (Donner et al., Citation2015), and their satisfaction is driven by how they are treated. Therefore, police must ascertain what they can do to enhance these attitudes. This study examines the impact of reassurance calls, which are a type of follow-up call to victims. In such conversations, the police can maintain a dialectic communication with the victim and provide not only much-needed information but also a secure avenue for the victim to have their voice (Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2017). Participants were victims reporting vehicle theft whose cases had been screened out within 48 hours from the time they reported the crime to the police. Vehicle crime was selected due to its high volume and low rates of detection. While all victims received the standard victim letter, treatment participants also received a reassurance call from a police officer. A follow-up satisfaction survey was then undertaken to assess the effect of these follow-up calls, with particular emphasis on subgroups of callers, including the method of reportage, type of vehicle crime, and victim demographics.

Literature Review

The instrumental interpretation of law enforcement argues that the role of the police is to be effective at addressing crime as victim satisfaction is based on how successful police are in securing arrests and convictions. However, perceptions of police conduct are more focused on fair treatment (Jonathan-Zamir & Harpaz, Citation2014) and professionalism (Tyler, Citation1988), not necessarily the outcomes of police performance. Within this framework, procedural justice theory purports that victim satisfaction is shaped by their experience with law enforcement agents (Tyler, Citation1988), with empirical studies based on panel and cross-sectional survey methodologies generally supporting this view (Bradford & Myhill, Citation2015; Fitzgerald, Citation2002; Jackson & Bradford, Citation2009; but cf. Weisburd et al., Citation2019).

Studies have identified what components of procedural justice predict victim satisfaction (see review in Clark et al., in press). The time taken to report and investigate a crime is vital as the longer this process takes, the less interested police are, and the lower the resultant victim satisfaction (Brandl & Horvath, Citation1991; Coupe & Griffiths, Citation1999; Kumar, Citation2018; Tewksbury & West, Citation2001; Zevitz & Gurnack, Citation1991). Moreover, Ahio’s (Citation2017) analysis of Met surveys concluded that the strongest predictor of satisfaction is providing reassurance, with victims’ feelings of being taken seriously as the second predictor (see also Myhill & Bradford, Citation2012). This line of inquiry on informational justice is influenced by the perceived thoroughness of an investigation, such as how long police spend at the scene (Brandl & Horvath, Citation1991). Several studies place importance on keeping victims updated (Ahio, Citation2017; Coupe & Griffiths, Citation1999; Fitzgerald, Citation2002; Newburn & Merry, Citation1990; Shapland et al., Citation1985; Tapley, Citation2003; van den Bos et al., Citation1997; Wemmers et al., Citation1995).

However, research on the effect of providing information on victim satisfaction is mixed. One of the few experiments on the subject identified greater satisfaction among households who received a police newsletter than those who had not (Hohl et al., Citation2010), suggesting that information is pertinent to perceptions of satisfaction. In contrast, a study in India found no increase in satisfaction among victims being given a copy of their complaint (Kumar, Citation2018). This finding is partly supported by research that found that it was less important what victims were told than how it was told (Ashworth, Citation1993). Furthermore, a Dutch study of victims’ interactions with police and prosecutors found that victims were more concerned with being treated with dignity and respect and less interested in police neutrality (Wemmers et al., Citation1995). Curiously, when examining victim satisfaction across several countries, Kesteren et al. (Citation2013) found that satisfaction was higher in jurisdictions where there were fewer referrals to support agencies. However, other research indicates that referrals for support do increase victim satisfaction (Ahio, Citation2017; Tewksbury & West, Citation2001). Given the complexity of the literature in this area, more research is warranted.

Murphy and Barkworth (Citation2014) utilized survey data collected from a representative sample of 1,204 Australians to show that the effect of procedural justice on victims’ willingness to report crime to police is context specific. The researchers found that procedural justice mattered to some victim types while instrumental factors mattered more for others. Specifically, victims who believed the outcome of their most recent contact with police had been more favorable were also more likely to say they would report crime to police in the future. However, once victims’ perceptions about procedural justice and police effectiveness were taken into account, the significant effect of outcome favorability disappeared for all victim types. Tankebe (Citation2009), in an examination of procedural fairness and legitimacy in Ghana, demonstrated that public cooperation with the police is shaped by utilitarian factors such as perceptions of current police effectiveness in fighting crime. Tankebe (Citation2009) further stipulates that the importance of perceived police effectiveness to public cooperation is a result of police legitimation deficits and the public’s alienation from the Ghana police. For some victim types, procedural justice is more important, while for other victim types, instrumental factors dominate their decision to report crime - and it cannot be ruled out that in some crime types the outcome of the investigation is more imoprtant, regardless of the way in which it was delivered.

Wolfe et al. (Citation2016), in a random sample of 1,681 mail survey respondents, examined whether the effect of procedural justice, distributive justice, and police effectiveness on police legitimacy evaluations operate in the same manner across individual and situational differences. In general, the authors found that procedural fairness has the strongest effect on police legitimacy. As such, while perceptions of police effectiveness are important, judgements around procedural justice are more crucial. Wolfe and McLean (Citation2017) administered 3,000 sixth-and seventh-grade students from 22 schools in the US to determine whether perceptions of police procedural injustice were more likely to lead to risky behavior that are conducive to victimization. In short, the researchers demonstrated that police procedural injustice was positively associated with risky lifestyles, which partially mediated the relationship between procedural injustice and violent victimization.

General Victim Satisfaction

A victim can be satisfied with how their crime is addressed while not having confidence in the overall police performance (Myhill & Bradford, Citation2012). Indeed, legitimacy, trust, and confidence are wider perceptions beyond specific interactions with the police. Confidence is focused on police delivering outcomes, whereas trust is rooted in the process (Jackson and Sunshine Citation2007). Zelditch (Citation2001) defines legitimacy as “when people believe that the decisions made, and the rules enacted by an authority are in some way right and proper and ought to be followed.” Tyler supports this interpretation, defining legitimacy from the viewpoint of the public (Tyler, Citation2008; Tyler & Huo, Citation2002). Moreover, Bottoms and Tankebe (Citation2017) argue that legitimacy is articulated from the perspectives of both the “audience” recognizing the power and the “power-holder” justifying that power, with a “dialogic” relationship between the two (Bottoms & Tankebe, Citation2017).

Skogan (Citation2006, Citation2012) concluded there is an “asymmetrical” relationship between police contact and confidence in the police: negative experiences with the police have a stronger effect than positive experiences with the police. To this extent, Skogan (Citation2006, Citation2012) argues that this dilemma is influenced by the fact that police encounters are usually set against the experience of being a victim or suspect, which is exacerbated by a negativity bias where victims are more likely to remember negative experiences than positive ones. Another study concluded that victims have a poorer view of police than non-victims because performance is a predictor of legitimacy (Aviv & Weisburd, Citation2016).

However, other research suggests that while poor police encounters reduce confidence in the police, the right contact can have a positive impact (Bradford et al., Citation2009b; Merry et al., Citation2011). Brandl et al. (Citation1994) also identified that positive encounters translate into favorable views of the police, while Jackson and Sunshine (2007) concluded that trust and confidence are generated by police treating people with dignity and respect. Together, these studies demonstrate a more “symmetrical” relationship between procedural justice and trust and confidence. In a systematic review of studies, Mazerolle et al. (Citation2013) found that procedural justice enhanced police legitimacy. Tankebe (Citation2014) reported that procedural justice is one of four factors (together with lawfulness, effectiveness, and distributive justice) that influence legitimacy.

Extraneous Factors Affecting Satisfaction with Police

Earlier studies treated victims as a single homogenous group (Felson & Pare, Citation2008). Although there is broad agreement that views of police are determined by how people are treated, it is crucial to understand that these views are contingent on the nature of the offense, the socio-demographic characteristics of victims, and the type of interaction victims have had with the police (Brandl et al., Citation1994; Hohl et al., Citation2010; Laxminarayan et al., Citation2013). We review this compartmentalized evidence below.

Crime Type

One early study found victims of serious crimes to be more satisfied than “volume crime” victims – that is, offenses that occur more frequently than others, like theft from person and vehicle theft (Poister & McDavid, Citation1978). Merry et al. (Citation2011) found that victims of hate crimes were less satisfied than burglary victims. A London satisfaction survey identified higher satisfaction for burglary victims than other volume crimes (MOPAC, Citation2021). This finding is likely to have been affected by victims of this type of crime being offered a face-to-face police interaction. Furthermore, two studies found more satisfaction with police for burglary than domestic incidents and assaults (Brandl & Horvath, Citation1991; Laxminarayan et al., Citation2013).

Age

Studies have demonstrated a relationship between age and victim satisfaction, with older victims more likely to be satisfied compared to younger victims (Brandl & Horvath, Citation1991; Kusow et al. Citation1997; Merry et al., Citation2011; Percy, Citation1980). Analyzing UK surveys, Hibberd (Citation2021) found a gradual increase in victim satisfaction from 16 to 64 years and then a rapid increase thereafter—which may be tied to police officers’ perceptions that older victims need more attention.

Gender

The literature identified mixed findings on the relationship between gender and victim satisfaction. Some studies found no such association (Brandl & Horvath, Citation1991; Felson & Pare, Citation2008; Kusow et al. 1997) while others found greater satisfaction among female victims (Merry et al., Citation2011; Tewksbury & West, Citation2001) and male victims (Norris & Thompson, Citation1993; Percy, Citation1980).

Ethnicity

Regarding the ethnicity of the victims, Percy (Citation1980) and Wu et al. (Citation2009) found that blacks were less satisfied than whites. A UK study found no significant differences in rankings among respondents based on race for overall satisfaction, courtesy and politeness, speed of response, concern, and helpfulness (Tewksbury & West, Citation2001), but a later study (Neyroud et al. Citation2022) suggests that ethnicity and race do matter, and minority members have lower satisfaction scores toward the police compared to whites. Similar observations were made by Tankebe (Citation2013) regarding legitimacy.

Mode of Reporting (Telephone/Online vs. in-Person)

The shift toward “technology-meditated service encounters” (Chicu et al., Citation2020) is on the rise, due to the need to cut costs: an email report is cheaper than a telephone report, which is cheaper than a face-to-face report at the police station, which are all cheaper than a police officer's visit to the victim's abode. However, a paucity of empirical evidence is seen on the effect of delivering a procedurally just police response via electronic means. Stafford (Citation2017a, Citation2017b) examined procedural justice in responding to “101 calls,” concluding that callers are more interested in receiving accurate information than the performance metric of response time. Cross (Citation2016), studying the impact of telephone calls made to elderly fraud victims in Canada, found increased victim satisfaction and lower rates of repeat victimization. However, as far as we are aware, no controlled evaluations have examined the effect of the mode of reporting on satisfaction.

Callbacks

As a matter of theoretical relevance, police callbacks are a tool by which law enforcement can develop trust and rapport with those they serve. To this extent, this method is fundamentally important in developing police-public relations as it can provide victims with a level of reassurance and demonstrates that law enforcement take the case seriously and have done their level best in investigating the reported incident. With relation to police legitimacy, callbacks are assumed to provide law enforcement with a platform to treat the victim with respect.

There are no published controlled experiments on the effect of police calling back victims to improve police perceptions (however see Clark et al., in press), so the relative effectiveness of call backs in policing research is presently unclear. Observational studies however do exist. Sixsmith et al. (Citation1997) examined the practice of calling back to accident and emergency (A&E) patients with domestic violence indicators to identify more victims; however, the practice was not positive. An Irish police report identified the value of callbacks to victims but concluded that these must be focused on high-harm crime and vulnerable victims (Anson et al., Citation2020). A US study found high satisfaction for victims given online access to updates on their case (Irazola et al., Citation2013). Wedlock and Tapley (Citation2016) noted the opportunity to use different methods of contact to improve satisfaction, but research is needed to ascertain what communication strategies are effective and which are not. Given the paucity of evaluations in this space, research is needed.

Methods

Settings

This randomized control trial (RCT) attempted to identify the causal effect of a callback policy, particularly in cases traditionally identified as suffering from low satisfaction. To this extent, we examined vehicle crimes that did not proceed to full investigation. The trial was conducted over a period of three months, from 1 September to 30 November 2021, but preceded by a pre-experimental pilot on 24 to 25 August 2021 to calibrate the methodology. The trial included all vehicle crimes reported in all but four of London’s 32 boroughs, representing 11 of the Metropolitan Polices Service 12 Basic Command Units.

Participants

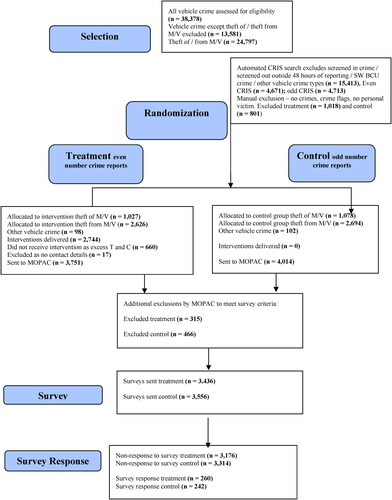

A cohort of 7,565 vehicle crime victims was included in the experiment (see CONSORT flowchart in ). Participants were identified by their unique Crime Report Investigation System (CRIS) number. This is automatically generated for each report of a crime in London. Participants are members of the public who reported the theft of a motor vehicle or theft from a motor vehicle in London, and their crime had been screened out within 48 hours.

Procedure

The screening decision is based on the Crime Assessment Principles (Metropolitan Police Service 2021c). These principles provide guidance on whether a volume crime should be screened in for further investigation; to emphasize, this process is not part of the research protocol, but rather part of police ordinary decisions. There are five principles that determine whether a case is screened in or out: 1) the victims’ willingness to prosecute, 2) the suspects’ identity being known, 3) the value associated to the crime (in terms of the object stolen or damanged ), 4) the availability of CCTV footage of the crime, and 5) the possibility of forensic leads. Where crimes are screened in, victims receive an enhanced service, with a local officer making contact or visiting them to further investigate potential leads. As such, screened-in crimes were excluded from the experiment.

Vehicle crime was selected as it is one of the most common volume crimes, and it has one of the lowest detection outcomes. Most cases are reported by phone, using 101 or 999, where Met Command and Control take initial details and determine whether a police unit should be dispatched. Based on vehicle crime reported during the trial, 87% of cases were initially investigated through the virtual telephone or online process (Met Police Metropolitan Police Service, Citation2021b). Crimes reported by telephone are passed by Met Command and Control to the Telephone and Digital Investigation Unit (TDIU) for initial investigation. Reporting is done through two methods. Some cases are sent as “live call transfers” while the victim is on the line. However, in most instances, a case is passed to a TDIU work file for the team to work through. Theft from a motor vehicle is one of nine categories of crime where victims will only be called back if further details are required to complete the initial investigation, or it is believed there may be a vulnerability, such as an elderly victim. For the theft of a motor vehicle, the TDIU will seek to call back the victim. If they cannot be contacted at the first attempt, the victim will be sent contact details for the Crime Management Services (CMS).

Following the initial investigation, the investigator decides whether to screen in the case for secondary investigation. Based on trial data, 64% of cases are screened out at this stage (Metropolitan Police Service, Citation2021a) and the victim is emailed the victim letter. This letter provides information required under the Victim’s Code (Ministry of Justice, Citation2021), including the crime reference number and links to victim support services and crime prevention advice.

The CONSORT flowchart of participants is presented in . Of the 38,378 vehicle crimes accessed, 7,565 participants met the eligibility criteria, with 3,653 and 3,912 randomly allocated to the treatment and control groups, respectively. Of the 3,653 eligible participants, 3,051 callbacks were attempted during the trial. 2,744 interventions were successfully delivered, with 307 failing to respond as the victim did not answer. This data represents treatment fidelity of approximately 90%. The online survey was sent by email and text to participants within seven days of the intervention. It is important to clarify that the method by which the survey was sent to participants is different from the method by which victims originally reported the incident. While all participants reported their incident by phone, email, or in-person, the survey was delivered via email and text. Overall, 3,436 invitations to participate in the survey were sent to treatment participants and 3,556 to the control. Given time constraints of the trial, the full cohort in the control (N = 3,912) and treatment groups (N = 3,653) did not receive the survey. There were 260 survey responses from the treatment group and 242 from the control.

Randomization

The randomization of participants to treatment and control caused that the groups to not differ in any systematic way other than the intervention applied (Ariel et al., Citation2022, p. 8). Every victim was assigned a unique police reference number, and this number presented an opportunity for a ready randomization process as these numbers are generated sequentially in an automated process. Therefore, participants with an even number were allocated for treatment, and those with an odd number were assigned to the control group. There are known issues associated with unconcealed allocation sequences, with a potential to influence outcome (Schulz & Grimes, Citation2002). However, in this experiment the likelihood of the randomization biasing the results is improbable as our design was double-blinded: the surveyors were unaware of the treatment allocation, and the victims were unaware of their involvement in the trial.

Interventions

Both groups received the standard response of a victim letter. Only the treatment group received the intervention of a reassurance call. We note that a text message was sent to every participant shortly before each intervention to advise that police would be calling. Three call attempts were then made in an attempt to talk to the victim. Calls were made Monday to Friday from 09:00 to 19:00. The trial team recorded whether an intervention had been delivered, how many attempts were made, and the length of the call. It is, moreover, unclear how long the call was made after the initial victimization as the case needed to be screened and accessed.

During the reassurance call, treatment participants were explained why their case had been screened out, demonstrating neutrality that this decision was based on the Crime Assessment Principles. Victims were shown empathy and the importance of reporting the crime was recognized. Accuracy was demonstrated by reading the report before making the call and then checking the facts with the victim. Participants were offered crime prevention advice and provided links to relevant websites if they wished to receive this. Some victims welcomed crime prevention advice while others declined it.

The trial team comprised 10 police officers and staff from CMS, with a police sergeant overseeing daily implementation. The team all volunteered and were experienced in dealing with victims of crime over the phone. The size of the team enabled four staff to deliver the interventions Monday to Friday throughout the trial.

Outcome Measures

We utilized an existing Metropolitan Police Service survey called the TDIU Survey, which was conducted by an external entity sitting within the Mayor’s Office (Opinion Research Services).Footnote1 This is an online survey sent to victims via both e-mail and text. The TDIU Survey had the advantage of being a large survey sent to both treatment and control victims, meaning every participant had an equal chance of completing it. Although online surveys have a bias against the elderly and the less well-off, it was assumed that few victims of vehicle crime in London have no access to the internet or a mobile phone. From an internal validity perspective, the error rate in terms of sample representation was assumed to be the same across the experimental arms.

A key challenge to overcome was the low response rate of the TDIU Survey – around 10% (MOPAC, Citation2021). Additional measures were thus put in place to increase it. First, the survey was sent out within seven days of the intervention, as opposed to 6 to 12 weeks later as normally would be the case. It was determined that greater proximity between the crime, intervention, and survey would make participants more inclined to complete it. To clarify, the survey was sent to the control group seven days after receiving their victim letter and to the treatment group seven days following the reassurance call. As such, there were no meaningful temporal differences between when the treatment and control groups received the survey, and participants were sent a reminder to complete the survey four days after the initial contact.

Statistical Analyses

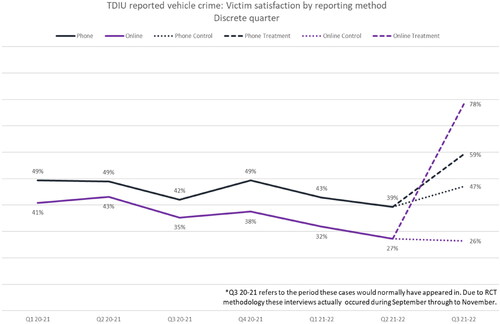

Given our experimental design and a sufficiently large sample size, we relied on straightforward statistics to estimate the causal effect of the intervention relative to control conditions. We provide a longitudinal perspective of the treatment effect, with multiple observations prior to the treatment taking place (Figure 2). Analyses were conducted on the survey responses utilizing descriptive statistics, and chi-square tests were applied to determine where differences were statistically significant at the usual 0.05 alpha level. The confirmatory sub-group analyses followed the same analytical approach, using chi-square statistics. We applied the “intention to treat” approach, with participants remaining in their allocated treatment condition even if they could not be contacted, switched groups, or completed partial surveys.

Results

Main Effects

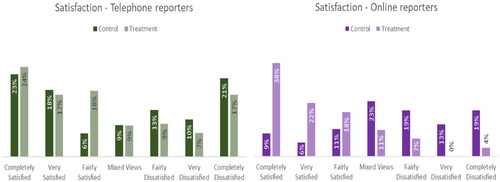

Overall, 62% of the treatment group expressed overall satisfaction relative to 40% for the control. This finding represents a 22-point (or 55%) improvement relative to control conditions. shows the comparison of satisfaction scores between participants who reported by telephone and those who reported online. Significantly more satisfaction was revealed among those in the treatment group than in the control for both reporting methods. However, there is a 51-point difference among participants reporting online compared to a 12-point discrepancy among those who reported by telephone.

Figure 2. Victim satisfaction telephone vs. online reporting (MOPAC, Citation2021).

illustrates the levels of satisfaction expressed by the treatment and control respondents. For victims reporting by telephone, there were no apparent differences between treatment and control in the “completely” and “very satisfied” categories. There is, however, an increase in the “fairly satisfied” category. This finding contrasts sharply with those reporting online, where there is a 29% increase in the “completely satisfied” category. Online reporters also expressed 16% more in the “very satisfied” category, but only 7% more as “fairly satisfied.”

Perceptions Based on the Reporting Method

Differences in the experiences of victims based on their method of reportage were detected. and list responses to these questions, comparing telephone and online reports. Of the 11 responses for telephone reportage, eight exhibited a statistically significant difference between the treatment and control conditions. In contrast, only four of the responses for online reportage demonstrated statistically significant differences. These results suggest that victims reporting via telephone are less receptive to the reassurance call.

Table 1. Results for telephone reportage.

Table 2. Results for online reportage.

Perceptions Based on the Vehicle Crime Type

Satisfaction was measured across the two vehicle crime types: theft from and theft of a motor vehicle. Theft from a motor vehicle (n = 5,460) was more common than theft of a motor vehicle (n = 2,105). Victims of theft from a motor vehicle exhibited higher levels of satisfaction from the treatment compared to victims of theft of a motor vehicle. Furthermore, among online reporters, victims of both vehicle crime types were far more satisfied by the reassurance call than victims who did not receive it (). While this result is the same for telephone reporters, differences between the treatment and control groups were least pronounced.

Table 3. Results for vehicle crime type by reportage method.

Victim Demographics

Victim satisfaction was assessed as conditional on demographic characteristics of age, gender, ethnicity, disability, and sexual identity (). Due to the low sub-group sizes, telephone and online reporters were combined. Statistically significant differences between the treatment and control groups were present in 10 of the 16 subgroups. Curiously, Black and Asian participants were more satisfied by the reassurance call. This result is also the case for participants under 55, females, and non-LGBT + participants.

Table 4. Results for demographic characteristics.

Call Characteristics

The lengths of calls were categorized as either brief (1 to 5 minutes) or long (6 minutes or more). Overall satisfaction for telephone reporters was 78% if the call was brief, compared to 51% if the call was long. Chi-square testing confirms that the difference was statistically significant (p = 0.003). However, no statistically significant difference was revealed for online reporters (p = 0.864), with 73% being satisfied when a call was “1 to 5 minutes” compared to 77% if it was longer.

Discussion

Reassurance callbacks, which fundamentally adhere to procedural justice theory, increase victim satisfaction. The 62% versus 40% satisfaction rate demonstrates a significant impact derived from a simple phone call to the victim, who is generally dissatisfied with the process (). The substential increase for victims reporting online compared to the increase for those reporting by telephone is informative, as it suggests a cost-effective policy of combining an efficient victimization reporting facility (online) with a victim support approach. Although there is some variation in contact with police depending on the vehicle crime type and whether they are referred to TDIU as a “live call transfer,” those reporting by telephone will experience one or more “doses” of procedural justice (Bradford et al., Citation2009a). The telephone conversation provides victims with a voice, which is missing from the online reporting platform. In addition, the call affords victims the opportunity to be listened to by the police operator or investigator, receive crime prevention advice, and take steps to ensure the crime does not happen again. Below, we discuss these results considering theory and practice.

Victim Satisfaction and Police Legitimacy

While victim satisfaction may not be a panacea for trust and confidence, it does appear to be a contributing factor. Research suggests that approval of police performance does matter for legitimacy. As suggested in the literature review, however, studies are unclear about the extent to which police contact can improve perceptions of law enforcement. Skogan (Citation2006, Citation2012) argued that contact is likely to undermine trust, while Bradford et al. (Citation2009b) and Merry et al. (Citation2011) contended that there might be a positive impact when procedural justice is applied. The findings from the present experiment go beyond the cautious optimism of Bradford et al. (Citation2009b) and Merry et al. (Citation2011) to identify clinically meaningful improvements through police contacts. In this study, the treatment group reported improved views following the reassurance callback by 36% for online and 27% for telephone reportage, while the control group improved 8% for online and 16% for telephone reportage, when considering previous satisfaction survey results. If there is a link between satisfaction and legitimacy of law enforcement, then reassurance calls provide a potent instrument to fill the legitimacy gap that contemprary policing experience around the globe.

Furthermore, reassurance callbacks provide the police with the opportunity to demonstrate “neutrality” if time is taken to explain the reasons for the screening decision. Based on previous victim surveys using the same instrument applied in this experiment, it appears that victims reporting online are deprived of this engagement and receive a limited dose of procedural justice. In this respect, the results show the impact of positive “expectancy disconfirmation” (Oliver, Citation1981). With their expectations exceeded, victims who have received negligible procedural justice in their reporting experience before the reassurance callback expressed that they were “pleasantly surprised” by the call.

Minority Victims

Furthermore, dissatisfaction from police performance is often stronger among minority groups, with black Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) often reporting lower approval rates than whites (Skinns et al., Citation2020). Our study suggests that reassurance calls resulted in stronger treatment effects among these group members. Satisfaction for White British in the treatment group increased by 16.6% but increased 32.9% and 33.2% for black and Asian participants, respectively. More research is needed to address these subgroup variations more formidably, preferably through qualitative research methods. Nevertheless, these results do indicate the potential benefits of calling back members of minority communities who might otherwise express more reserved or negative attitudes toward the criminal justice system (see Table 1 in Tankebe, Citation2013).

The Low Response Rate Problem

The willingness of victims to take part in the survey was low. Self-selection in survey responses creates a bias in favor of those who choose to complete it, who may not share the same attributes as those who do not. However, this is not always the case, as the number of participants taking part in a survey (i.e. response rate) is not as important as the representative nature of the effective sample size compared to the sampling frame (see Langley et al., Citation2021; Mazerolle et al., Citation2013). More pragmatically, low response rates are presently the standard, particularly in the online surveys commonly used in policing studies. Thus, we do not anticipate that the low response rate issue will improve. For example, a survey of victims of violent crime in Missouri achieved an 8.8% response rate (Avery et al., Citation2020). Langley et al. (Citation2021) and Mazerolle et al. (Citation2013) encountered 14% and 13% response rates, respectively, in their procedural justice experiments (see also Kennedy & Hartig, Citation2019).

These results therefore remain informative despite the response rate problem. It seems that only face-to-face interviews can achieve a 60% response rate or more (e.g. Tankebe, Citation2013). However, these experiments are not only costly, but also limited to areas where the participants live close to the interviewing firm, particularly in research where the instrument does not interact with the intervention (see Chapter 4 in Ariel et al., Citation2022). Face-to-face interviews of the thousands of victims who participated in this experiment would take a long time to complete and the treatment effect may therefore fade away by the time all participants were surveyed. Moreover, diverting from the ordinary way in which MOPAC conducts its victim satisfaction surveys would not allow us to compare the post-test results with the baseline data MOPAC ordinarily collects. Thus, while far from ideal, the online survey is the optimal approach in experiments within this line of inquiry.

Conclusions

Telephone and online police investigations are likely to increase as more demand is placed on policing in the 21st century, with more self-service and automation (Metropolitan Police Service, Citation2021d). However, the police must not abandon procedural justice when focusing on managing utility and the increased workload. The advantages of a reassurance call are its relative simplicity and that it is within the control of the police. The results of this trial demonstrate not only the immediately achievable benefits but also the critical role of the telephone investigator as a point of contact between the victim and police. Therefore, we conclude that the findings provide a solution to reverse the decline in victim satisfaction in the UK (). Of equal importance, we show an avenue for eliciting procedural justice that can be applied in operational policing as part of an investigatory effort that places the victim at the center. Further research is necessary to explore the impact of reassurance calls on other crime types as well as different methods of intervention. Given the simplicity of the policy examined, the test provides clear supportive evidence of the benefits gained by implementing reassurance callbacks to victims.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (181.3 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

References

- Ahio, N. (2017). Improving victim satisfaction in volume crime investigations: The role of police actions and victim characteristics [PhD Thesis]. London Southbank School of Applied Sciences.

- Anson, S., Cochrane, L., Iannelli, O., & Muraszkiewicz, J. (2020). The experiences of victims of crime with Garda Siochana: Interim report. Police Authority Trilateral Research.

- Ariel, B., Bland, M., & Sutherland, A. (2022). Experimental designs. Sage.

- Ashworth, A. (1993). Victim impact statements and sentencing. Criminal Law Review, 498–509.

- Avery, E. E., Hermsen, J. M., & Towne, K. (2020). Crime victimisation, neighbourhood social cohesion and perceived police effectiveness. Wiley Online Library.

- Aviv, G., & Weisburd, D. (2016). Reducing the gap in perceptions of legitimacy of victims and non-victims: The importance of police performance. International Review of Victimology, 22(2), 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269758015627041

- Bates, L. J., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Martin, P. (2015). Comparing police and public perceptions of a routine traffic encounter. Police Quarterly, 18(4), 442–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611115589290

- Bottoms, A., & Tankebe, J. (2017). Police legitimacy and the authority of the state. Hart Publishing Ltd.

- Bradford, B., Jackson, J., & Stanko, E. A. (2009a). Contact and confidence: Revisiting the impact of public encounters with police. Policing and Society, 19(1), 20–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460802457594

- Bradford, B., & Myhill, A. (2015). Triggers of change to public confidence in the police and criminal justice system: Findings from the Crime Survey of England & Wales panel experiment. Criminology & Criminal Justice, 15(1), 23–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1748895814521825

- Bradford, B., Stanko, E. A., & Jackson, J. (2009b). Using research to inform policy: The role of public attitude surveys in understanding public confidence and police contact. Policing, 3(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1093/police/pap005

- Brandl, S. G., Frank, J., Worden, R. E., & Bynum, T. S. (1994). Global and specific attitudes toward the police: Disentangling the relationship. Justice Quarterly, 11(1), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418829400092161

- Brandl, S. G., & Horvath, F. (1991). Crime victim evaluation of police investigative performance. Journal of Criminal Justice, 19(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(91)90008-J

- Chicu, D., Pamies, M., & Ryan, G. (2020). Exploring the Influence of the Human Factor on Customer Satisfaction in Call Centres. Business Research Quarterly, 22(2), 83–95.

- Clark, B., Ariel, B., & Harinam, V. (in press). How Should the Police Let Victims Down? The Impact of Reassurance Call-Backs by Local Police Officers to Victims of Vehicle and Cycle Crimes: A Block Randomized Controlled Trial. Police Quarterly. Police Quarterly.

- Coupe, R. T., Ariel, B., & Mueller-Johnson, K. (Eds.). (2019). Crime solvability factors: Police resources and crime detection. Springer Nature.

- Coupe, R. T., & Griffiths, M. A. (1999). The influence of police actions on victim satisfaction in burglary investigations. International Journal of the Sociology of Law, 27(4), 413–431. https://doi.org/10.1006/ijsl.1999.0097

- Cross, C. (2016). ‘I’m anonymous, I’m a voice at the end of the phone’: A Canadian case study into the benefits of providing telephone support to fraud victims. Crime Prevention & Community Safety, 18(3), 228–243. https://doi.org/10.1057/cpcs.2016.10

- Donner, C., Maskaly, J., Fridell, L., & Jennings, W. G. (2015). Policing and procedural justice: A state-of-the-art review. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 38(1), 153–172. https://doi.org/10.1108/PIJPSM-12-2014-0129

- Felson, R. B., & Pare, P. (2008). Gender and the victim’s experience with the criminal justice system. Social Science Research, 37(1), 202–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.06.014

- Fitzgerald, M. (2002). Policing for London. Willan.

- Freeman, L. (2013). Support for victims: Findings from the crime survey for England & Wales. Ministry of Justice Analytical Series.

- Hibberd, M. (2021). Crime detection isn’t key to Victim satisfaction. Police Foundation Workshop to Police Senior Leaders, 14 December 2021. https://www.police-foundation.org.uk/2021/08/crime-detection-isnt-key-to-victim-satisfaction/

- HM Inspectorate of Constabulary. (2014). Policing in austerity: Meeting the challenge.

- Hodgkinson, T., Andresen, M. A., Ready, J., & Hewitt, A. N. (2020). Let’s go throwing stones and stealing cars: Offender adaptability and the security hypothesis. Security Journal, 10, 1–20.

- Hohl, K., Bradford, B., & Stanko, E. A. (2010). Influencing trust and confidence in the London Metropolitan Police. British Journal of Criminology, 50(3), 491–513. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azq005

- Irazola, S., Williamson, E., Niedzwiecki, E., Debus-Sherill, S., & Stricker, J. (2013). Evaluation of the state-wide Automated Victim Information & Notification Programme (Final Report). U.S. Department of Justice.

- Jackson, J., & Bradford, B. (2009). Crime, policing & social order: On the expressive nature of public confidence in policing. British Journal of Sociology, 60(3), 493–521. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-4446.2009.01253.x

- Jackson, J., & Sunshine, J. (2007). Public confidence in policing: A neo-Durkheimian perspective. British journal of criminology, 47(2), 214–233.

- Joffee, S. (2009). Validating Victims: Enforcing Victim’s Rights through Mandatory Mandamus. Utah Law Review, 2009(1), 241.

- Jonathan-Zamir, T., & Harpaz, A. (2014). Police understanding of the foundations of their legitimacy in the eyes of the public: The case of commanding officers in the Israel National Police. British Journal of Criminology, 54(3), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjc/azu001

- Jonathan-Zamir, J., & Harpaz, T. (2018). Predicting support for procedurally just treatment: The case of the Israel National Police. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 45(6), 840–862. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854818763230

- Kennedy, C., & Hartig, H. (2019). Response rates to telephone surveys have resumed their decline. PEW Research Center.

- Kesteren, J., Dijik, J., & Mayhew, P. (2013). The international crime victims survey: A retrospective. International Review of Victimology, 20(1), 49–69.

- Kumar, V. T. K. (2018). Comparison of impact of procedural justice and outcome on victim satisfaction: Evidence from victims’ experiences with registration of property crimes in India. Victims & Offenders, 13(1), 122–141.

- Kusow, A. M., Wilson, L. C., & Martin, D. E. (1997). Determinants of victim satisfaction with the police: The effects of residential location. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management, 20(4), 655–664. https://doi.org/10.1108/13639519710192887

- Langley, B., Ariel, B., Tankebe, J., Sutherland, A., Beale, M., Factor, R., & Weinborn, C. (2021). A simple checklist, that is all it takes: A cluster randomised controlled field trial on improving the treatment of suspected terrorists by police. Journal of Experimental Criminology, 17(4), 629–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-020-09428-9

- Laxminarayan, M., Bosmans, M., Porter, R., & Sosa, L. (2013). Victim satisfaction with criminal justice: A systematic review. Victims & Offenders, 8(2), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2012.763198

- Lay, W., Ariel, B., and Harinam, V. (in press). Recalibrating the Police to Focus on Victims Using Police Records. Policing: A Journal of Policy and Practice.

- Mazerolle, L., Antrobus, E., Bennett, S., & Tyler, T. R. (2013). Shaping citizen perceptions of police legitimacy: A randomised field trial of procedural justice. Criminology, 51(1), 33–63. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00289.x

- Merry, S., Power, N., McManus, M., & Alison, L. (2011). Drivers of public trust and confidence in the UK. International Journal of Police Science & Management, 14(2), 118–134.

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2021a). Crime Recording & Investigation Bureau report: Analysis of volume crime recording. 2021.

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2021b). Crime Recording & Investigation Bureau report: Analysis of victim satisfaction.

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2021c). Crime Assessment Principles. July.

- Metropolitan Police Service. (2021d). Contact & Resolution Service Policy Paper. August.

- Ministry of Justice. (2021). Victims code: Code of practice for victims of crime, updated 2021. Crown Copyright.

- MOPAC. (2019). A better police service for London—MOPAC London surveys. https://governance.enfield.gov.uk/documents/s76264/metrics_ts2b.pdf.

- MOPAC. (2021). A better service for London: MOPAC London Surveys FY Q2 2020–2021 results. Mayor’s Office for Policing and Crime.

- Murphy, K., & Barkworth, J. (2014). Victim willingness to report crime to police: Does procedural justice or outcome matter most? Victims & Offenders, 9(2), 178–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/15564886.2013.872744

- Myhill, A., & Bradford, B. (2012). Can police enhance public confidence by improving quality of service? Results from two surveys in England & Wales. Policing and Society, 22(4), 397–425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2011.641551

- Newburn, T., & Merry, S. (1990). Keeping in touch: Police victim communication in two areas. HM Stationary Office.

- Neyroud, P., Neyroud, E., & Kumar, S. (2022). Police-led diversion programs: Rethinking the gateway to the formal criminal justice system. In Handbook of issues in criminal justice reform in the United States (Jeglic, E. L., & Calkins, C. (Eds). (pp. 599–620). Springer.

- Norris, F. H., & Thompson, M. P. (1993). The victim in the system: The influence of police responsiveness on victim alienation. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 6(4), 515–532. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.2490060408

- Oliver, R. L. (1981). Measurement and evaluation of satisfaction in retail settings. Journal of Retailing, 57(3), 25–48.

- Orth, U. (2002). Secondary victimization of crime victims by criminal proceedings. Social Justice Research, 15(4), 313–325. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021210323461

- Percy, S. L. (1980). Response time and citizen evaluation of the police. Journal of Police Science and Administration, 8, 75–86.

- Poister, T. H., & McDavid, J. C. (1978). Victims’ evaluations of police performance. Journal of Criminal Justice, 6(2), 133–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/0047-2352(78)90060-0

- Schulz, K. F., & Grimes, D. A. (2002). Allocation concealment in randomised trials: Defending against deciphering. Lancet, 359(9306), 614–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07750-4

- Shapland, J., Willmore, J., & Duff, P. (1985). Victims in the criminal justice system. Gower Publishing.

- Sixsmith, D. M., Weissman, L., & Constant, F. (1997). Telephone follow-up for case finding of domestic violence in an emergency department. Academic Emergency Medicine, 4(4), 301–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1553-2712.1997.tb03553.x

- Skinns, L., Sorsby, A., & Rice, L. (2020). “Treat them as a human being”: Dignity in police detention and its implications for ‘good’ police custody. British Journal of Criminology, 60(6), 1667–1688.

- Skogan, W. G. (2006). Asymmetry in the impact of encounters with police. Policing and Society, 16(2), 99–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439460600662098

- Skogan, W. G. (2012). Assessing asymmetry: The life course of a research project. Policing and Society, 22(3), 270–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2012.704035

- Stafford, A. (2017b). Providing victims of crime with information on police response activity: The challenges faced by the police non-emergency call-handler. Police Journal: Theory, Practice and Principles, 91(4), 297–315. https://doi.org/10.1177/0032258X17731685

- Stafford, A. B. (2017a). Calling the police: Managing contact and expectation through non-emergency call handling [PhD thesis]. University of Bristol.

- Tankebe, J. (2009). Public cooperation with the police in Ghana: Does procedural fairness matter? Criminology, 47(4), 1265–1293. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2009.00175.x

- Tankebe, J. (2013). Viewing things differently: The dimensions of public perceptions of police legitimacy. Criminology, 51(1), 103–135. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-9125.2012.00291.x

- Tankebe, J. (2014). Police legitimacy. In M. D. Reisig & R. J. Kane (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of police and policing. (238–259 pp). Oxford University Press.

- Tapley, J. (2003). From ‘good citizen’ to ‘deserving client’: The relationship between victims of violent crime and the state using citizenship as the conceptualizing tool [PhD thesis]. University of Southampton.

- Tewksbury, R., & West, A. (2001). Crime victims’ satisfaction with police services: An assessment in one urban community. The Justice Professional, 14(4), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/1478601X.2001.9959626

- Tyler, T. R. (1988). What is procedural justice? Criteria used by citizens to assess the fairness of legal procedures. Law & Society Review, 22(1), 103–135. https://doi.org/10.2307/3053563

- Tyler, T. R. (2008). Legitimacy & Cooperation: Why do people help the police fight crime in their communities? Ohio State Journal of Criminal Law, 6, 231–275.

- Tyler, T. R., & Huo, Y. J. (2002). Trust in the lLaw: Encouraging public cooperation with the police and courts. Social Forces, 82(2), 840–841.

- van den Bos, K., Vermunt, R., & Wilke, H. A. M. (1997). Procedural & distributive justice: What is fair depends more on what comes first than what comes next. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 72(1), 95–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.72.1.95

- Victim Support Report. (2011). Left in the dark: Why victims of crime need to be kept informed. www.victimsupport.org.uk.

- Wedlock, E., & Tapley, J. (2016). What works in supporting victims of crime: A rapid evidence assessment. Victim’s Commissioner and the University of Portsmouth, HM Stationary Office.

- Weisburd, D., Majmundar, M. K., Aden, H., Braga, A., Bueermann, J., Cook, P. J., Goff, P. A., Harmon, R. A., Haviland, A., Lum, C., Manski, C., Mastrofski, S., Meares, T., Nagin, D., Owens, E., Raphael, S., Ratcliffe, J., & Tyler, T. (2019). Proactive policing: A summary of the report of the National Academies of Sciences. Asian Journal of Criminology, 14(2), 145–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11417-019-09284-1

- Wemmers, J., van der Leeden, R., & Steensma, H. (1995). What is procedural justice; criteria used by Dutch victims to assess fairness of criminal justice procedures. Social Justice Research, 8(4), 329–350. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02334711

- Wolfe, S. E., & McLean, K. (2017). Procedural injustice, risky lifestyles, and violent victimization. Crime & Delinquency, 63(11), 1383–1409. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128716640292

- Wolfe, S. E., Nix, J., Kaminski, R., & Rojek, J. (2016). Is the effect of procedural justice on police legitimacy invariant? Testing the generality of procedural justice and competing antecedents of legitimacy. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 32(2), 253–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-015-9263-8

- Wu, Y., Sun, I. Y., & Triplett, R. A. (2009). Race, class or neighborhood context: Which matters more in measuring satisfaction with police? Justice Quarterly, 26(1), 125–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820802119950

- Zelditch, M. (2001). Process of legitimisation: Recent developments in new directions. Social Psychology Quarterly, 64(1), 4–17. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090147

- Zevitz, R. G., & Gurnack, A. M. (1991). Factors related to elderly crime victims’ satisfaction with police service: The impact of Milwaukee’s ‘Grey Squad’. The Gerontologist, 31(1), 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/31.1.92