ABSTRACT

Here we examined the possibility of a relationship of sensory processing sensitivity (SPS) with chronotype in a German-speaking sample of N = 1807 (1008 female, 799 male) with a mean age of 47.75 ± 14.41 y (range: 18–97 y). The data were collected using an anonymous online questionnaire (Chronotype: one item of the Morning-Evening-Questionnaire, as well as typical bedtimes on weekdays and weekends; SPS: German version of the three-factor model ; Big Five: NEO-FFI-30) between 21 and 27 April 2021. Results. We found morningness to correlate with the SPS facet low sensory threshold (LST), while eveningness correlated to aesthetic sensitivity (AES) and marginally significant to ease of excitation (EOE). Discussion: The results show that the correlations between chronotype and the Big Five personality traits are not consistent with the direction of the correlations between chronotype and the SPS facets. The reason for this could be different genes that are responsible for the individual traits influence each other differently depending on their expression.

Introduction

Chronotype

Chronotype is concerned with individual differences in preferred bed and rise times, preferred times of physical and mental/cognitive activity and with the sleep–wake rhythm in general (Adan et al. Citation2012). Humans differ significantly in their chronotype which is regarded a personality-like trait (Randler et al. Citation2017). Morning people usually get out of bed easily and have their senses clear within a few minutes. Furthermore, they achieve their best cognitive performance in the morning. In schools, for example, students morningness was positively correlated with positive affect, both during the first and last lesson of the school day (Randler and Weber Citation2015). However, morning people become tired in the early evening and may need a nap (Rahafar et al. Citation2018). On the contrary, evening types prefer sleeping longer in the morning, having problems with getting up during social schedules. People high in eveningness can work better in the afternoon and even at night (Adan et al. Citation2012). Moreover, men are usually more evening oriented than women (Randler and Engelke Citation2019).

Chronotype changes during childhood and puberty. Children are usually morning oriented, while juveniles tend to be evening oriented. Adults show a similar distribution in the extreme values (morning orientation/evening orientation). However, most adults do not show extreme values. These people are thus often described as neither type. In late adulthood, there is a renewed tendency towards a morning orientation (Randler et al. Citation2017). Chronotype is related to many psychological and physiological aspects (for an overview, see Adan et al. Citation2012). Even though at present, it is unclear what the causes of the correlations are. Concerning personality, Big Five traits were repeatedly associated with Chronotype by different research groups (see, e.g., Randler et al. Citation2017). The links between chronotype and the Big Five personality facets remain comparable within different age groups (Randler Citation2008).

Sensory processing sensitivity

Another personality trait that has increasingly become the focus of research since the late 1990s is the sensory processing sensitivity (SPS). People who exhibit SPS perceive impressions of the outside world earlier and more strongly. Stressors are experienced amplified (compared to people who show no or milder expression of this personality trait), which leads to an intensified responsiveness to the environment and often goes hand in hand with the feeling of being overwhelmed (Jagiellowicz et al. Citation2016). Aron and Aron (Citation1997) suggested that individual differences in SPS are partially determined by the reactivity of the behavioural inhibition system (BIS). The BIS, along with the behavioural activation system (BAS) and the fight/flight system, is one of the three brain systems hypothesized to control emotional behaviour (Gray Citation1991). In general, SPS is manifested in an increased awareness of sensory impressions that are both physical (e.g., sounds, smells, other’s emotional expressions; Aron et al. Citation2012; Jagiellowicz et al. Citation2016) and psychological in nature (e.g., higher empathy, depth of processing, self-reflection; Acevedo et al. Citation2018; Aron and Aron Citation1997) and are not limited to one’s own person (Acevedo et al. Citation2017; Aron et al. Citation2012; Jagiellowicz et al. Citation2011). Moreover, people with the SPS trait also process sensory information more deeply, resulting in a stronger emotional reactivity, a higher awareness of subtle stimuli and a lower threshold above which those individuals are overstimulated (Acevedo et al. Citation2017; Jagiellowicz et al. Citation2011; Yano and Oishi Citation2021; Yano et al. Citation2020).

SPS and other personality traits

Concerning the Big Five personality traits, SPS was related to Openness (r = 0.14) and Neuroticism (r = 0.40), but not to Conscientiousness, Extraversion, or Agreeableness (Lionetti et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, it was correlated to the BIS (r = 0.32; Smolewska et al. Citation2006), and the BAS reward facet (r = 0.16; Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Also, SPS was related to Negative Affect (r = 0.34) in adults (Lionetti et al. Citation2019).

SPS and eveningness correlated positively with the two Big Five dimensions “openness” and “neuroticism” while morningness was related to “extraversion,” “agreeableness” and “conscientiousness” (Randler et al. Citation2017; Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Concerning the BIS/BAS: SPS is suggested as the personality trait that emerges from the neuro-psychological basis of the BIS (Aron and Aron Citation1997). Therefore, persons high in SPS are also high in BIS functioning (Aron and Aron Citation1997; Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Regarding Chronotype and the BIS/BAS: Morningness correlates to BIS total and BIS fear (Randler et al. Citation2014). Moreover, chronotype is related to positive affect, with morningness showing larger effect sizes than eveningness (Randler and Weber Citation2015).

It is still unclear how chronotype and personality interact, but it is conceivable that there are genes that determine both, probably in co-variance. Furthermore, it would also be possible that the chronotype causally influences personality and behaviour or that personality and behaviour causally influence the chronotype, or it may be operating via a feedback loop. Currently, there is not enough research to answer this question, but further work will help to better understand the links between chronotype, personality and behaviour. The first aim of this paper is therefore to present an updated model of the influences on chronotype, helping identify possible starting points for further research.

Revised framework of factors influencing chronotype

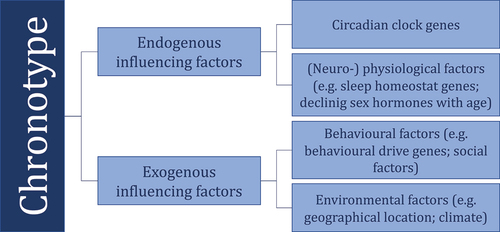

In the work of Ashbrook et al. (Citation2020), the authors present a first draft of a conceptual framework that illustrates the different factors influencing the chronotype. Four different facets are mentioned in this work, which interact with each other and together determine the chronotype. These facets are presented as (a) circadian clock genes, (b) sleep homeostat genes, (c) behavioural drive genes, and (d) environment. While the genes related to circadian activity and to homeostatic sleep are based on Borbély’s two process model of sleep (Borbély Citation1982), what Ashbrook et al. (Citation2020) call “behavioural drive genes” is less well understood and research regarding this topic is limited. In their paper, the authors present several mutations that lead to affected individuals having a lower need for sleep (4–6.5 h) to be refreshed than is assumed on average for a person with a healthy sleep rhythm. Moreover, these people feel a higher intrinsic pressure/desire to be efficient and productive. This manifests itself, for example, in the fact that these individuals have high-pressure jobs or several jobs at the same time. The authors describe this personality trait as “behavioural drive” and the underlying genes as “behavioural drive genes.” The phenotypically occurring consequences of these mutations and the role that the effects have on personality and sleep behaviour result in the hypothesis that Borbély’s model must be extended by further facets to describe the origin of the chronotype. They propose an extension of Borbély’s model to include the facets “environment” and “behavioural drive genes.” The environmental influence on chronotype has been shown by meta-analysis and large-scale studies (e.g., for latitudinal influence: Randler and Rahafar Citation2017). The expression of these facets determines the timing and duration of an individual’s sleep. To extend this conceptual framework, we propose on the one hand a grouping of these influencing variables into endogenous and exogenous factors and on the other hand an extension of the facet “sleep homeostatic genes” to “(neuro-) physiological factors” to consider potential influences of (neuro-) physiological processes that may only indirectly/at certain life stages affect sleep timing and duration (see ).

Figure 1. Expanded conceptual framework of factors influencing chronotype based on the preliminary work of Ashbrook et al. (Citation2020).

Further objectives

In addition to the search for causal relationships between chronotype and personality, there are also areas of personality that have not yet been investigated for relationships with chronotype. To fully clarify the question of association, research can approach the answer from two sides. On one hand, causality should be examined more closely, and on the other, it should be clarified in which areas of personality (beyond those known so far) and how pronounced relationships to the chronotype can be found.

We contribute to the clarification of this question by approaching the answer from the side of the hitherto unknown connections between chronotype and personality. The present study investigates whether SPS is related to Chronotype. We used the three-factor model of Smolewska et al. (Citation2006) to determine SPS in the current sample. In this model, SPS is measured by the scales low sensory threshold (LST), ease of excitation (EOE), and aesthetic sensitivity (AES). People with LST exceed the limit of pleasant arousal faster when confronted with external stimuli (e.g., bright lights or foul smells), whereas the EOE facet indicates an increased sensitivity to both internal and external stimuli (e.g., being stressed when multitasking is required; Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Both facets are associated with negative emotionality, while the scale AES of Smolewska et al. (Citation2006) three-factor model is more likely to be associated with positive emotionality. AES describes the openness to and ability to feel pleasure through aesthetic experiences and positive stimuli.

We expect the results to indicate differences in the SPS of chronotypes. Moreover, we hypothesize (H1) eveningness to correlate to AES, since late chronotypes are associated with artistic qualities, creativity, and creative thinking processes (see, e.g., Caci et al. Citation2004; Díaz-Morales Citation2007; Giampietro and Cavallera Citation2007; Wang and Chern Citation2008). Moreover, we expect a negative relationship of LST with morningness (H2) since both facets were repeatedly reported to correlate differently directed with neuroticism (see, e.g., DeYoung et al., Citation2007; Lipnevich et al. Citation2017; Smolewska et al. Citation2006; Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021; Staller and Randler Citation2021). For the EOE facet, we opted for an exploratory rather than a hypothesis-driven approach.

Methods

Participants

Overall, sample size was N = 1807 (1008 female, 799 male) with a mean age of 47.75 ± 14.41 y (range: 18–97 y). Educational levels were distributed as follows: n = 10 (0.55%) had no degree, n = 211 (11.68%) had 9 y of schooling, n = 508 (28.11%) had O-level (middle degree, “Realschule,” about 10 y), n = 418 (23.13%) A-level (“Abitur”), n = 599 (33.15%) obtained a university degree, and n = 61 (3.38%) had doctorate degrees.

Research instruments

For measuring chronotype, one item of the German version of the Morning-Evening-Questionnaire MEQ was used (Griefahn et al. Citation2001): “One hears about ‘morning’ and ‘evening’ types of people. Which ONE of these types do you consider yourself to be?” with the answer options (the item was coded using the guidelines of the original questionnaire): “Definitely a morning type (coded as 6),” “Rather more a morning type than an evening type (coded as 4),” “Rather more an evening type than a morning type (coded as 2),” “Definitely an evening type (coded as 0).” The retest reliability over a 6-y period of this item was high: r = 0.741 (Spearman Rank correlation); 786 participants of the Randler et al. (Citation2017) study also partook in the present study (423 females, 363 males, age: 51.12 ± 13.12 at t1). Second, typical bedtimes on weekdays and weekends were elicited: “What is your typical bedtime during the week?” or “What is your typical bedtime on weekends?.” Participants indicated the exact time of their bedtimes (HH:MM). Parameters were used as a combination of a subjective estimate and a behavioral measure to validate the results further, since late chronotypes are correlated with late bedtimes (see, e.g., Roenneberg et al. Citation2007).

Based on the Highly Sensitive Person Scale (HSPS) of Aron and Aron (Citation1997) and Smolewska et al. (Citation2006) three-factor model, Konrad and Herzberg (Citation2019) developed a German version with three factors: Ease of Excitation (EOE; N = 10 items), Aesthetic Sensitivity (AES; 5 items), and Low Sensory Threshold (LST; 11 items). The items have a five-point format (0 = strongly disagree, 1 = disagree, 2 = partly agree/disagree, 3 = agree, 4 = strongly agree). Examples are as follows: “I become unpleasantly aroused when a lot is going on around me.” (EOE), “I seem to be aware of subtleties in my environment.” (AES), and “I am bothered by intense stimuli, like loud noises or chaotic scenes.” (LST). The three-factor structure was supported by two confirmatory factor analyses in independent samples. Cronbach’s α for the subscales was high: Ease of Excitation = 0.87, Aesthetic Sensitivity = 0.70, Low Sensory Threshold = 0.91. Similar, the retest reliabilities for the three factors were high, ranging from 0.81 (AES) to 0.86 (LST).

The big five personality factors were measured with the German version of the NEO-FFI-30, which includes 30 Items (Körner et al. Citation2008). Each personality factor (neuroticism, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness) were computed as the means of the six corresponding items. The internal consistencies (Cronbach’s α) of the five scales of the 30-item version given by the test authors ranged from r = 0.67 (openness to experience) to r = 0.81 (neuroticism) and were comparable to those of the 60-item version of the NEO-FFI (Körner et al. Citation2008).

Procedure

An invitation to participate in this study was sent to all people registered on www.wisopanel.net. this platform includes about 12 000 people who are interested in partaking in online studies. Participation was voluntary and unpaid. The data collection took place between 21 and 27 April 2021. The typical bedtimes on weekdays and weekends were visually inspected by the third author, values that were not plausible (outside the range of 19 and 5 h) were omitted, some values have been corrected from a 12-h-format, e.g., 11- to the 24-h-format, 23 h. As there have been also missing values, sample size for the bedtime analysis was slightly reduced.

For carrying out statistical procedures, we used the SAS 9.4 software package for Windows (Cary, North Carolina, USA). Ordinal regression and parametric regressions were computed for analyzing the effect of different predictors (the Big Five personality dimensions and HSPS factors) on chronotype and bedtimes. The variables were entered simultaneously.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the HSPS factors and the Big Five Personality factors are shown in . The internal consistencies found in the present sample are comparable with the values reported by the test authors (Konrad and Herzberg Citation2019; Körner et al. Citation2008).

Table 1. Means and Cronbach’s α for HSPS factors and the Big Five Personality factors (N = 1807).

The distribution of the chronotype item is depicted in . Most participants fell into the medium groups, and there was a slight preponderance of evening types compared to morning types. Mean bedtime during the week was 23.10 ± 1.31 h (N = 1787), at weekends slightly later: 23.37 ± 1.39 h (N = 1791). The correlation between those two bedtimes was high (r = 0.818, p < 0.0001, N = 1782). Chronotype was also significantly associated with the two bedtime measures, weekday: r = −0.516 (p < 0.0001, N = 1787) and weekend: r = −0.533 (p < 0.0001, N = 1791).

Table 2. Chronotype distribution (N = 1807).

The ordinal regression of the chronotype item indicated that the strongest factor associated with chronotype was conscientiousness (see ). For morningness, small associations were found with high education, and openness to experience. Interestingly, the three sensory processing sensitivity factors were differentially associated with chronotype, LST was related to morningness, whereas EOE (marginally significant) and AES were more closely related to eveningness (see ). Age and gender were not associated with chronotype in this sample.

Table 3. Ordinal regression analyses for the chronotype item.

Like the chronotype results, conscientiousness was related to earlier bedtime during the week and on weekends (see ). High education and female gender were also associated with earlier bedtimes. For age, the effect was differential: younger persons reported earlier bedtimes during the week and later bedtimes at weekends. Besides the small correlation between openness to experience and bedtime during the week, the Big Five personality factors apart from conscientiousness were not related with bedtimes. LST was associated with earlier bedtimes – mirroring the result regarding chronotype. On the other hand, AES was related to later bedtime on weekends and during the week.

Table 4. Parametric regression analyses for bedtimes (weekday and weekend).

Discussion

General results: The study sample shows comparable characteristics with previously published research. The distribution of chronotypes in the present sample corresponds to the distribution in other studies (e.g., Roenneberg et al. Citation2007). The bedtimes of the participants did not differ significantly from other German samples collected at a similar time (see, e.g., Staller et al. Citation2022). Early bedtimes correlated with female gender in this sample. In the meta-analysis of Randler and Engelke (Citation2019), it was also reported that males were on average more evening oriented than females in younger study samples, however, the differences become smaller over time.

Chronotype, education, and Conscientiousness: A certain triangular relationship between high education, morningness and conscientiousness can be derived. In terms of Big Five personality traits, conscientiousness was shown to be a strong predictor of chronotype and bedtimes in this sample. In other study groups, conscientiousness was described as the strongest predictor of the Big Five scales for chronotype (specifically: morningness; see, e.g.,, Adan et al. Citation2012; Staller et al. Citation2021). In general, literature shows morningness to correlate strongly with conscientiousness (see, e.g.,, Randler Citation2008). Equidirectional, high education also correlates with conscientiousness (see, e.g.,, O’Connor and Paunonen Citation2007; Poropat Citation2009). In our sample, we were able to show a positive relationship between the two variables morningness/early bedtimes with high education. With regard to the correlations with conscientiousness of chronotype and high education individually, the connection between these two may be strengthened. Moreover, conscientiousness as well as morningness correlate with self-efficacy (Staller et al. Citation2021) which is a predictor for high education (Valentine et al. Citation2004). This again points to a possible strengthening of the relationship and opens up room for further study.

Results related to sensory processing sensitivity: factors were not uniformly associated with chronotype. Research data on the relationship between chronotype and the Big Five facet openness are very inconsistent. In the present sample, morningness is related to openness to experience, replicating the results of, e.g.,, Randler (Citation2008). But other findings showed no significant (e.g., Staller and Randler Citation2021) or a negative (e.g., Russo et al. Citation2012; Tsaousis Citation2010) correlation to morningness. Moreover, Staller and Randler (Citation2021) reported a positive relationship of openness with eveningness. Literature reports, the AES facet of SPS to correlate the strongest to the Big Five facet openness (Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Given these results, we would have expected AES to correlate with the chronotype facet correlating to openness in this sample. Therefore, the missing relationship between morningness and AES seems unusual, since morningness was the chronotype facet correlating negatively to openness in this sample. Likewise, the positive relationship between morningness and LST partly contradicts the directional correlations of both variables with other personality traits. Even though morningness was repeatedly reported to have a negative relationship with neuroticism (see, e.g.,, DeYoung et al., Citation2007; Lipnevich et al. Citation2017; Staller and Randler Citation2021; Tonetti et al. Citation2009) it also correlates to the LST facet which in turn correlates positively with neuroticism (e.g., Smolewska et al. Citation2006; Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021). We would have expected LST to correlate negatively with morningness, since this facet was repeatedly shown to correlate negatively to neuroticism in literature. Moreover, Aron and Aron (Citation1997) suggested persons high in SPS are also high in BIS functioning, because the BIS is the neuro-psychological basis of the SPS personality facet. But, LST has a weak association with BIS (Smolewska et al. Citation2006; Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021), while morningness correlates to BIS total and BIS fear (Randler et al. Citation2014).

EOE for that matter relates the strongest of all SPS facets to BIS (Smolewska et al. Citation2006). A strong correlation to BIS is associated with a cautious attitude to avoid negative consequences. The relationship of EOE to BIS highlights the tendency to be overwhelmed by stimuli and to experience concentration problems (Smolewska et al. Citation2006). EOE may therefore be the strongest predictor of low wellbeing (Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021). In the current sample, EOE relates marginally significant to eveningness which in this chain of reasoning is consistent with the correlation of eveningness to low wellbeing (see, e.g.,, Buschkens et al. Citation2010; Drezno et al. Citation2019; Díaz-Morales et al. Citation2013). But eveningness correlates with AES, which tends to be associated with positive characteristics and high wellbeing (Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021). Furthermore, LST is associated with adverse traits and low wellbeing (Sobocko and Zelenski Citation2021) but contradictorily, morningness (which correlates to LST in this sample) relates to greater life satisfaction and high wellbeing (see, e.g.,, Buschkens et al. Citation2010; Drezno et al. Citation2019; Díaz-Morales et al. Citation2013) Based on the correlations of the chronotype facets and the SPS facets with well-being reported in the literature, we would have expected different relationships between these facets.

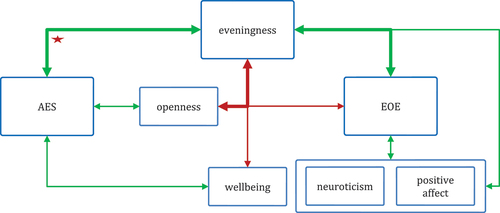

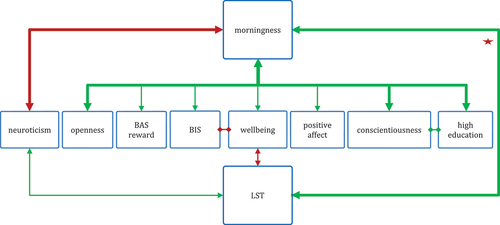

The BAS reward scale showed a small correlation with EOE and AES (Smolewska et al. Citation2006). This suggests that individuals who score high in both EOE and AES respond to threat/punishment (BIS functioning) and rewarding stimuli (BAS reward; Smolewska et al. Citation2006). Smolewska et al. (Citation2006) suggest that individuals who have high levels of both EOE and AES experience higher levels of positive affect in response to rewarding stimuli. In the sample studied, EOE (marginally significant) and AES were found to be related to eveningness. Since the chronotype is a personality-like trait, the correlations of eveningness with both EOE (marginally significant) and AES may indicate a potential link between individuals high in eveningness and positive affect as suggested by Smolewska et al. (Citation2006). However, the effect sizes were rather small. This is further supported by the general correlation between the chronotype and positive affect, although within the chronotype morningness is reported to correlate more with positive affect than eveningness (see, e.g.,, Randler and Weber Citation2015). Furthermore, no direct correlation between eveningness and BAS reward could be found. Contradictorily, morningness correlates with BAS reward (see, e.g.,, Hasler et al. Citation2010) but not with EOE and AES. provide an illustrated summary of the described interrelationships. They exemplify both the results shown here as well as the findings reported in the literature.

Figure 2. Relationships between the chronotype facet eveningness and the related SPS facets AES and EOE. Please note that EOE was found to be marginally significant to eveningness. Green arrows indicate positive relationships; red arrows indicate negative relationships. Thick arrows indicate results found in this study; thin arrows indicate results from literature. The asterisk marks the relationship which lead to accepting the hypothesis concerning eveningness and AES (H1).

Figure 3. Relationships between the chronotype facet morningness and the related SPS facet LST. Green arrows indicate positive relationships; red arrows indicate negative relationships. Thick arrows indicate results found in this study; thin arrows indicate results from literature. The asterisk marks the relationship which lead to rejecting the hypothesis concerning morningness and LST (H2).

Conclusion

Our results show differences in the chronotypes in SPS. We were able to support H1 (positive relationship of eveningness with AES) but had to reject H2 (negative relationship of morningness with LST) in this sample. Furthermore, we could show that eveningness tends to relate with EOE (results were marginally significant). How exactly these different facets of personality interact with each other is not yet clear to us, as the correlations of different traits with each other are sometimes directed differently than would be expected. Examples of this are the positively directed relationship between LST, neuroticism (+) and morningness (+), while morningness is negatively related to neuroticism (-). One possible explanation for the inconsistent direction of the associations is as yet unknown physiological mechanisms that play a role. In addition, the effects of confounding factors cannot be completely ruled out. The relationships between SPS, chronotype and the Big Five personality traits should therefore be investigated further. Until now, there has been no clear answer to the question of how chronotype and personality are causally related to each other, or which aspect significantly influences the other. In the present work, we were able to show that the personality facet of SPS is also related to chronotype. Moreover, we have discussed a wide range of connections linked to both chronotype and SPS as described in the literature. Some of these associations seem to contrast with each other pointing out research gaps. The data suggest that facets that shape personality in opposite directions can correlate in the same direction with chronotype. Our results may therefore indicate that chronotype and personality are not determined by the same genes. This highlights the need for more research to understand the causality of the relationships. The discussion of a broad range of relationships led to present a flowchart of the ramifications that can be used to conduct further research on this topic despite not raising all variables ourselves.

Limitations

Limitations of this study may be found in the choice of methods. Chronotype was represented by a single question instead of a validated questionnaire. However, Randler et al. (Citation2017) showed that the use of a single self-assessment question is as reliable as a larger questionnaire. Furthermore, a questionnaire with a more biological background could also have been chosen, such as the Zuckerman–Kohlmann Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Acevedo B, Aron E, Pospos S, Jessen D. 2018. The functional highly sensitive brain: a review of the brain circuits underlying sensory processing sensitivity and seemingly related disorders. Phil Trans R Soc B. 373:20170161. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0161

- Acevedo BP, Jagiellowicz J, Aron E, Marhenke R, Aron A. 2017. Sensory processing sensitivity and childhood quality’s effects on neural responses to emotional stimuli. Clin Neuropsychiatry: J Eval Clin. 14(6):359–373.

- Adan A, Archer SN, Hidalgo MP, Di Milia L, Natale V, Randler C. 2012. Circadian typology: a comprehensive review. Chronobiol Int. 29:1153–1175. doi:10.3109/07420528.2012.719971

- Aron EN, Aron A. 1997. Sensory-processing sensitivity and its relation to introversion and emotionality. J Pers Soc Psychol. 73:345–368. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.2.345

- Aron EN, Aron A, Jagiellowicz J. 2012. Sensory processing sensitivity: a review in the light of the evolution of biological responsivity. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 16:262–282. doi:10.1177/1088868311434213

- Ashbrook LH, Krystal AD, Fu YH, Ptáček LJ. 2020. Genetics of the human circadian clock and sleep homeostat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 45:45–54. doi:10.1038/s41386-019-0476-7

- Borbély AA. 1982. A two process model of sleep regulation. Hum Neurobiol. 1:195–204.

- Buschkens J, Graham D, Cottrell D. 2010. Well‐being under chronic stress: is morningness an advantage? Stress Health. 26:330–340. doi:10.1002/smi.1300

- Caci H, Robert P, Boyer P. 2004. Novelty seekers and impulsive subjects are low in morningness. Eur Psychiatry. 19:79–84. doi:10.1016/j.eurpsy.2003.09.007

- DeYoung CG, Hasher L, Djikic M, Criger B, Peterson JB. 2007. Morning people are stable people: circadian rhythm and the higher-order factors of the big five. Pers Individ Dif. 43:267–276.

- Díaz-Morales JF. 2007. Morning and evening-types: exploring their personality styles. Pers Individ Dif. 43:769–778. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.002

- Díaz-Morales JF, Jankowski KS, Vollmer C, Randler C. 2013. Morningness and life satisfaction: further evidence from Spain. Chronobiol Int. 30:1283–1285. doi:10.3109/07420528.2013.840786

- Drezno M, Stolarski M, Matthews G. 2019. An in-depth look into the association between morningness–eveningness and well-being: evidence for mediating and moderating effects of personality. Chronobiol Int. 36:96–109. doi:10.1080/07420528.2018.1523184

- Giampietro M, Cavallera GM. 2007. Morning and evening types and creative thinking. Pers Individ Dif. 42:453–463. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2006.06.027

- Gray JA. 1991. The neuropsychology of temperament. In: Strelau J, Angleitner A, editors. Explorations in temperament. Perspectives on individual differences. Boston, MA: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-0643-4_8

- Griefahn B, Künemund C, Bröde P, Mehnert P. 2001. Zur Validität der deutschen Übersetzung des Morningness-Eveningness-Questionnaires von Horne und Östberg. Somnologie - Schlafforschung und Schlafmedizin. 5:71–80. doi:10.1046/j.1439-054X.2001.01149.x

- Hasler BP, Allen JJ, Sbarra DA, Bootzin RR, Bernert RA. 2010. Morningness–eveningness and depression: Preliminary evidence for the role of the behavioral activation system and positive affect. Psychiatry Res. 176:166–173. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2009.06.006

- Jagiellowicz J, Aron A, Aron EN. 2016. Relationship between the temperament trait of sensory processing sensitivity and emotional reactivity. Soc Behav Pers J. 44:185–199. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.2.185

- Jagiellowicz J, Xu X, Aron A, Aron E, Cao G, Feng T, Weng X. 2011. The trait of sensory processing sensitivity and neural responses to changes in visual scenes. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 6:38–47. doi:10.1093/scan/nsq001

- Konrad S, Herzberg PY. 2019. Psychometric properties and validation of a German high sensitive person scale (HSPS-G). Eur J Psychol Assess. 35:364–378. doi:10.1027/1015-5759/a000411

- Körner A, Drapeau M, Albani C, Geyer M, Schmutzer G, Brähler E. 2008. Deutsche Normierung des NEO-Fünf-Faktoren-Inventars (NEO-FFI) (German Norms for the NEO-Five Factor Inventory). Zeitschrift für Medizinische Psychologie. 17:133–144.

- Körner A, Geyer M, Roth M, Drapeau M, Schmutzer G, Albani C, Schumann S, Brahler E. 2008. Personlichkeitsdiagnostik mit dem NEO-Fünf-Faktoren-Inventar: die 30-item-Kurzversion (NEO-FFI-30) [personality diagnostic using the NEO-Five-factor-inventory: The 30-Item short version (NEO-FFI-30)]. Psychotherapie, Psychosomatik und Medizinische Psychologie. 58:238–245. doi:10.1055/s-2007-986199

- Lionetti F, Pastore M, Moscardino U, Nocentini A, Pluess K, Pluess M. 2019. Sensory processing sensitivity and its association with personality traits and affect: a meta-analysis. J Res Pers. 81:138–152. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2019.05.013

- Lipnevich AA, Credè M, Hahn E, Spinath FM, Roberts RD, Preckel F. 2017. How distinctive are morningness and eveningness from the Big Five factors of personality? A meta-analytic investigation. J Pers Soc Psychol. 112:491. doi:10.1037/pspp0000099

- O’Connor MC, Paunonen SV. 2007. Big Five personality predictors of post-secondary academic performance. Pers Individ Dif. 43:971–990. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2007.03.017

- Poropat AE. 2009. A meta-analysis of the five-factor model of personality and academic performance. Psychol Bull. 135:322. doi:10.1037/a0014996

- Rahafar A, Mohamadpour S, Randler C. 2018. Napping and morningness-eveningness. Biol Rhythm Res. 49:948–954. doi:10.1080/09291016.2018.1430491

- Randler C. 2008. Morningness–eveningness, sleep–wake variables and big five personality factors. Pers Individ Dif. 45:191–196. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.007

- Randler C, Baumann VP, Horzum MB. 2014. Morningness–eveningness, Big Five and the BIS/BAS inventory. Pers Individ Dif. 66:64–67. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.010

- Randler C, Engelke J. 2019. Gender differences in chronotype diminish with age: A meta-analysis based on morningness/chronotype questionnaires. Chronobiol Int. 36:888–905. doi:10.1080/07420528.2019.1585867

- Randler C, Faßl C, Kalb N. 2017. From lark to owl: developmental changes in morningness-eveningness from new-borns to early adulthood. Sci Rep. 7:1–8. doi:10.1038/srep45874

- Randler C, Rahafar A. 2017. Latitude affects morningness-eveningness: evidence for the environment hypothesis based on a systematic review. Sci Rep. 7:1–6. doi:10.1038/srep39976

- Randler C, Schredl M, Göritz AS. 2017. Chronotype, sleep behavior, and the Big Five personality factors. SAGE Open. 7:2158244017728321. doi:10.1177/2158244017728321

- Randler C, Weber V. 2015. Positive and negative affect during the school day and its relationship to morningness–eveningness. Biol Rhythm Res. 46:683–690. doi:10.1080/09291016.2015.1046249

- Roenneberg T, Kuehnle T, Juda M, Kantermann T, Allebrandt K, Gordijn M, Merrow M. 2007. Epidemiology of the human circadian clock. Sleep Med Rev. 11:429–438. doi:10.1016/j.smrv.2007.07.005

- Russo PM, Leone L, Penolazzi B, Natale V. 2012. Circadian preference and the big five: the role of impulsivity and sensation seeking. Chronobiol Int. 29:1121–1126. doi:10.3109/07420528.2012.706768

- Smolewska KA, McCabe SB, Woody EZ. 2006. A psychometric evaluation of the highly sensitive person scale: the components of sensory-processing sensitivity and their relation to the BIS/BAS and “Big Five”. Pers Individ Dif. 40:1269–1279. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2005.09.022

- Sobocko K, Zelenski JM. 2015. Trait sensory-processing sensitivity and subjective well-being: distinctive associations for different aspects of sensitivity. Pers Individ Dif. 83:44–49. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.03.045

- Staller N, Großmann N, Eckes A, Wilde M, Müller FH, Randler C. 2021. Academic self-regulation, chronotype and personality in university students during the remote learning phase due to COVID-19. Front. Educ. 6:681840. doi:10.3389/feduc.2021.681840

- Staller N, Kalbacher L, Randler C. 2022. Auswirkungen eines pandemiebedingten Lockdowns auf Lernverhalten und Schlafqualität bei deutschen Studierenden. Somnologie. 26:1–8. doi:10.1007/s11818-022-00346-8

- Staller N, Randler C. 2021. Relationship between Big Five personality dimensions, chronotype, and DSM-V personality disorders. Front Net Physiol. 4. doi:10.3389/fnetp.2021.729113

- Tonetti L, Fabbri M, Natale V. 2009. Relationship between circadian typology and big five personality domains. Chronobiol Int. 26:337–347. doi:10.1080/07420520902750995

- Tsaousis I. 2010. Circadian preferences and personality traits: a meta‐analysis. Eur J Pers. 24:356–373. doi:10.1002/per.754

- Valentine JC, DuBois DL, Cooper H. 2004. The relation between self-beliefs and academic achievement: a meta-analytic review. Educ Psychol. 39:111–133. doi:10.1207/s15326985ep3902_3

- Wang SC, Chern JY. 2008. The ‘night owl’learning style of art students: creativity and daily rhythm. Int J Art Des Educ. 27:202–209. doi:10.1111/j.1476-8070.2008.00575.x

- Yano K, Kase T, Oishi K. 2020. The associations between sensory processing sensitivity and the Big Five personality traits in a Japanese sample. J Individ Differ. 42:84–90. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000332

- Yano K, Oishi K. 2021. Replication of the three sensitivity groups and investigation of their characteristics in Japanese samples. Curr Psychol. 42:1371–1380.