ABSTRACT

This study examined the psychometric properties and longitudinal changes of the self-reporting Traditional Chinese version of Biological Rhythms Interview for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (C-BRIAN-SR) among healthy controls (HC) and patients with major depressive episode (MDE). Eighty patients with a current MDE and 80 HC were recruited. Assessments were repeated after two weeks in HC, and upon the discharge of MDE patients to examine the prospective changes upon remission of depression. The C-BRIAN-SR score was significantly higher in the MDE than HC group. The concurrent validity was supported by a positive correlation between scores of C-BRIAN-SR, Insomnia Severity Index and the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale. C-BRIAN-SR negatively correlated MEQ in the MDE group (r = .30, p = 0.009), suggesting higher rhythm disturbances were associated with a tendency toward eveningness. A moderate test-retest reliability was found (r = .61, p < 0.001). A cut-off of 38.5 distinguished MDE subjects from HC with 82.9% of sensitivity and 81.0% of specificity. C-BRIAN-SR score normalized in remitted MDE patients but remained higher in the non-remitted. The C-BRIAN-SR is a valid and reliable scale for measuring the biological rhythms and may assist in the screening of patients with MDE.

Introduction

Social rhythm and circadian entrainment

Circadian rhythm is an internal oscillation of bodily functions in approximate 24-hour cycles in response to day-night diurnal change. To synchronize with the external environment, our endogenous rhythm is entrained by environmental times cues (or zeitgebers), such as light, temperature, feeding pattern, and social activity (Mistlberger and Skene Citation2005). It has been found that the social cues are capable to entrain the circadian rhythm (Aschoff et al. Citation1971). Social rhythm, comprising repetitive social routines including eating habits, leisure activity, work, and exercise pattern, which are shaped by familial, social, and occupational roles (Monk et al. Citation1991), has been increasingly investigated in its influence in circadian rhythm and human health.

Social rhythm and affective disorders

In 1981, Ehlers et al. proposed that life events can cause disturbance in social zeitgebers, which disrupts the social and biological rhythm and leads to mood disturbances (The Social Zeitgeber Theory) (Ehlers et al. Citation1988). The impact of social rhythm was further exemplified in a recent study showing that a more regular social rhythmicity was associated with fewer depressive and anxiety symptoms in 3284 community adults (Sabet et al. Citation2021). In addition, an inverse correlation was shown between the severity of depression and social rhythm stability (Brown et al. Citation1996). The disturbance among patients with bipolar disorder appeared to be even more conspicuous, with a lower social rhythm regularity and/or social disruptions being consistently reported during both hypomanic and euthymic states (Ashman et al. Citation1999; Boland et al. Citation2012; Bullock et al. Citation2011) and remission (Levenson et al. Citation2015). More importantly, social rhythm regularity has been shown to significantly predict the time to participants’ first prospective onset of affective episode (Shen et al. Citation2008). Consequently, Interpersonal and Social Rhythm Therapy (IPSRT) has been developed and found to reduce symptoms and relapse in patients with bipolar disorder (Frank Citation2007; Steardo et al. Citation2020). Taken together, current evidence suggests that social rhythm may play an important role in the illness trajectories and serve as an opportunity to allow intervention to modify illness outcomes.

Social rhythm measurements

At present, there are several clinical assessment tools in measuring the social rhythm. The Social Rhythm Metric (SRM) was the first instrument designed to quantify social rhythm regularity (Monk et al. Citation1990). Using SRM, a social metric score is obtained by summing up the number of “hit,” which is defined as an event that is performed within 45 minutes of the habitual time of that event (Monk et al. Citation1990). Nevertheless, it requires meticulous recording of daily events over 12 weeks to obtain a reliable measure (Monk et al. Citation1991). The Biological Rhythms Interview for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (BRIAN) (Giglio et al. Citation2009) was developed as a 21-item interviewer-rated instrument to evaluate five specific areas including sleep, activity, social rhythm, dietary habits, and predominant rhythm (Giglio et al. Citation2009). In contrast to the SRM, the BRIAN assesses the general regularity over the past 15 days without the need for daily recording over days and weeks.

The BRIAN was initially designed as an interviewer-rated instrument but was also adapted to be a self-reporting questionnaire in several other studies (Allega et al. Citation2018; Meyrel et al. Citation2022). The BRIAN has been translated to simplified Chinese, yet there is currently no study in validating the self-report version of Chinese BRIAN (C-BRIAN-SR), which would be more applicable and convenient for clinical applications. In this study, we aim to translate the BRIAN into Traditional Chinese, and to examine the psychometric properties of the self-reporting version of C-BRIAN-SR in both healthy subjects (HC) and patients with major depressive episodes (MDE). Additionally, we compared the C-BRIAN-SR between patients who achieved remission after treatment to the healthy controls to delineate if there is any residual social irregularity upon resolution of depressive symptoms.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedures

This study is part of the larger study that investigated the prospective change of circadian measures during the course of MDE in acute psychiatric inpatients. Adult patients aged 18–70 who were admitted to the university-affiliated in-patient psychiatric unit of Shatin Hospital from Feb 2021 to Dec 2022 were consecutively screened for eligibility. Participants with a clinical diagnosis of major depressive episode (MDE) diagnosed by their treating psychiatrists according to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) were recruited and included both major depressive disorder (MDD) and bipolar disorder (BD). Patients who fulfilled the below criteria were excluded: i) Seasonal pattern specifier of the DSM-5 ii) A current or past history of schizophrenia, mental retardation, organic mental disorder, or substance use disorder. (Presence of anxiety disorders will not be excluded provided it was not the primary diagnosis.) iii) A diagnosis of mixed episode or Young Mania Rating Scale of 12 or higher. iv) Presence of psychotic symptoms. v) Mentally incapacitated person. Eighty healthy control (HC) participants without any current or lifetime psychiatric disorders were recruited from the community through advertisement (i.e. poster, leaflet) in Hong Kong. Patient or HC who were regular shift workers or having significant medical condition/hearing impairment/speech deficit leading to incapability of completing clinical assessments were excluded. This research was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the relevant committees on human experimentation and with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethics approval of this study was provided by the Joint Chinese University of Hong Kong – New Territories East Cluster Clinical Research Ethics Committee (Ref. No.: 2022.056). Informed consent of the participants was obtained after the nature of the procedures had been fully explained prior to the study. Half of the HC were evaluated again after two weeks while the MDE group completed the follow-up assessment on their day of discharge. Only the data from the HC was used to examine the test-retest reliability as biological rhythm changes were anticipated after treatment for MDE.

Measurements

The Traditional Chinese self-report version of Biological Rhythms Interview for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (C-BRIAN-SR)

The English version was first translated to Chinese by a bi-lingual (Chinese-English) psychiatrist. An independent psychiatrist proficient in both Chinese and English performed the back-translation. The translated version was further refined and discussed among psychiatrists with expertise in mood disorders and circadian rhythm (JWYC, SWHC, YKW). The C-BRIAN-SR was adapted to be a self-reporting format in this study. All items are rated with a 4-point scale, indicating a frequency from “not at all” (scoring 1) to “often” (scoring 4). The total BRIAN scores range from 18 to 72, where the higher value indicates the higher socio-biological rhythm disturbance (Appendix A).

Structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale with atypical depression supplement (SIGH-ADS)

This is a structural clinical interview conducted by psychiatrist in assessing depression severity and atypical neuro-vegetative symptoms (Williams et al. Citation1994). MDE patients were assessed using SIGH-ADS both at the baseline and upon discharge from the hospital. Remission of depression was defined as a score of 7 or less with the 17-item Hamilton Depression Scale embedded in the SIGH-ADS.

Morningness and eveningness questionnaire (MEQ)

The MEQ is a 19-item self-assessment questionnaire (Horne and Ostberg Citation1976) used in evaluating the circadian preference. It consists of 19 questions, and the score ranges from 16 to 86, in which a higher score represents a greater tendency to morningness. The following cut-offs were used for the classification of circadian types: 16–30 = definite evening type, 31–41 = moderate evening type, 42–58 = intermediate type, 59–69 = moderate morning type, and 70–86 = definite morning type. This scale has been translated and validated into Chinese and used in local studies (Chan et al. Citation2014, Citation2020).

Insomnia severity index (ISI)

The ISI is a 7-item self-report questionnaire for assessing the severity and impact of sleep insomnia with a total score of 28 (Bastien et al. Citation2001). Items are rated in 5 categories: severity of current sleep problem, satisfactory of current sleep pattern, sleep interference level to daily functioning, noticeability of impairment, and the level of distress caused by sleep problem. All items are scored with a 5-point Likert scale from 0 = no problem to 4 = very severe problem. The scale has been validated in Chinese with good psychometric properties (Yu Citation2010).

Hospital anxiety and depression scale (HADS)

The HADS is a self-assessment scale that comprises 7 questions for anxiety and 7 questions for depression for assessment of anxiety and depression (Zigmond and Snaith Citation1983). Items are answered in a 4-point (0–3) response category and rated separately in the two subscales. The total score is the sum of the 14 questions, ranging from 0 to 21. It has been translated and validated locally (Leung et al. Citation1999).

Statistical analysis

For detection of a significant difference of C-BRIAN between MDE and HC, we took reference of the mean and standard deviation of BRAIN scores among MDE patients and HC of prior studies. The effect sizes ranged from 0.67 to 1.3 (Allega et al. Citation2018; He et al. Citation2022; Pinho et al. Citation2016). Using a more conservative effect size of 0.67, to achieve 95% power with 5% type I error, the required sample size is 59 subjects per group, supporting an adequate sample size in the current study. The between-group differences on the clinical outcomes were compared with independent t-test between controls (HC Group) and patients with major depressive episode (MDE Group). Owing to a higher percentage of female in the MDE group, linear regression analyses were performed for group comparisons for all the clinical scale outcomes, with gender adjusted in all the analyses. Construct validity was assessed through exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation to extract the factors. Convergent validity was assessed by Pearson’s correlations between C-BRIAN-SR and MEQ, ISI, HADS in the HC group and MDE group, respectively. Cronbach’s alpha was used to evaluate the internal consistency. The test-retest reliability of the total C-BRIAN-SR score was performed among the control group and analyzed by using Pearson’s correlation between two time points. Pearson’s correlation coefficients are considered as weak (0–0.3), low (0.3–0.5), moderate (0.5–0.7), high (0.7–0.9), and very high (0.9–1) (Mukaka Citation2012). IBM Statistical Package for Social Science (SPSS) version 27.0 was used to perform the statistical analysis.

Results

Baseline clinical characteristics of MDE and HC groups

The mean age of MDE patients (which included 62 patients with major depressive disorder and 18 patients with bipolar disorder) and the HC group were 41.9 ± 15.5 and 39.9 ± 15.3 years (mean ± SD) respectively. There was a greater proportion of female participants in MDE groups (74% vs 55%, p = 0.013). A significantly higher mean HADS scores was found in the MDE group than the HC group in both anxiety (12.4 ± 4.4 vs 5.6 ± 3.5, p < 0.001) and depression subscales (12.1 ± 4.9 vs 5.3 ± 3.4, p < 0.001). Patients with MDE also showed a significantly higher mean ISI score than the HC group (17.9 ± 6.5 vs 7.7 ± 4.5, p < 0.001). The MEQ score showed no significant difference between the two groups. The mean C-BRIAN-SR total score was higher among patients with MDE than the controls (47.3 ± 10.3 vs 31.7 ± 7.9, p < 0.001). In addition, the mean scores for each domain of the C-BRIAN-SR were higher in patients with MDE group than those in the HC group ().

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of study participants.

Exploratory factor analysis for the structure of C-BRIAN-SR

The sampling adequacy for the analysis was confirmed with the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure, KMO = .890. Bartlett’s test of sphericity Χ2 (210) = 1614.96, p < 0.001. All 21 items were subjected to the exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation. Four factors with eigenvalues greater than 1 emerged from analysis of the C-BRIAN-SR and accumulatively accounted for 60.8% of the total variance. Factor loadings of individual C-BRIAN-SR items relation to the four-factor solution are shown in , termed sleep/social rhythm factor, sleep/chronotype factor, social factor and eating factor. Items loading was compatible with the factors theoretically intended.

Table 2. Exploratory factor analysis of the C-BRIAN-SR.

Correlation between C-BRIAN-SR to clinical outcomes

At baseline, a negative correlation was found between the C-BRIAN-SR score and the MEQ score, r = −.299, p = 0.009 in the MDE group, which indicates that greater rhythm disturbance was associated with a tendency toward eveningness. Significant positive correlations of the C-BRIAN-SR score to the ISI and HADS scores were found in both MDE and HC groups. All of the correlations remained significant at the follow-up ().

Table 3. Correlation between C-BRIAN-SR to clinical outcomes.

Reliability of C-BRIAN-SR

The C-BRIAN-SR scale demonstrated a high level of internal consistency in all 160 subjects with a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.92 for the 18 items (), and a value of 0.91 for 21 items. The corrected item-total correlation is low for Item 4 (0.369) and Item 18 (0.304), however, their “Cronbach’s alpha if the item is deleted” remained high (0.922 for Item 4, and 0.923 for Item 18). In this regard, we did not delete these two items from the questionnaires, as this allows better comparisons of BRIAN scores with other studies. Nonetheless, we repeat the analyses with the C-SR-BRAIN without item 4 and 18 for the group comparisons, correlations with clinical outcomes and test-retest reliability and the results did not change. (Supplementary Tables S1–S3). A correlation coefficient showed that there is a significant correlation between the two assessment time points in the HC group (r = .61, p < 0.001, not shown in the table), suggesting moderate test-retest reliability of the C-BRIAN-SR scale .

Table 4. Reliability analysis of the C-BRIAN-SR.

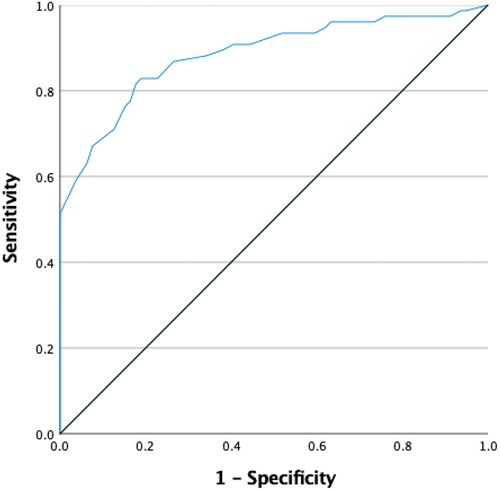

ROC analysis

C-BRIAN-SR showed a good performance in screening and distinguishing rhythms disturbance between patients with MDE and healthy controls with an AUC of 0.88, ranging from 0.83 to 0.94. It showed 82.9% of sensitivity and 81.0% of specificity with the best cut-off value at 38.5 (see ).

C-BRIAN-SR in remitted MDE vs non-remitted MDE group and controls

There was no significant difference of baseline C-BRIAN-SR score among non-remitted patients and remitted patients (49.8 ± 10.9 vs 44.8 ± 9.6, p = 0.06). Nonetheless, the C-BRIAN-SR score was significantly higher in the non-remitted patients than those who remitted at the follow-up assessments (43.2 ± 9.7 vs 31.2 ± 8.1, p < 0.001). No significant C-BRIAN-SR difference was found between remitted MDE and the controls after treatment (31.2 ± 8.1 vs 33.4 ± 8.8, p = 0.56).

Discussion

Our study showed that the C-BRIAN-SR is a reliable instrument with good internal consistency and construct validity in MDE patients and healthy controls. A cut-off score of 38.5 to differentiate healthy controls from the patients with MDE with a sensitivity of 82.9% and specificity of 81.0%, supporting that C-BRIAN-SR may serve as a convenient self-reporting screening instrument to identify subjects with mood disturbance.

Biological rhythm and mood disturbances

The result in our study is consistent with a number of studies which reported higher social biological rhythm irregularity in patients with major depressive episodes than healthy controls (Cho et al. Citation2018; Moro et al. Citation2014; Rosa et al. Citation2013; Szuba et al. Citation1992). Particularly, our results in measuring rhythm regularity in MDE patients with C-BRIAN-SR is highly consistent with a recent study applying BRIAN as an interviewer-rated instrument in Chinese (He et al. Citation2022), which also showed a higher BRIAN score in patients with major depressive disorder than healthy controls (39.5 ± 12.0 vs 26.4 ± 7.0), and a similar cut-off of 35 to differentiate MDD patients from healthy controls.

Interestingly, our study showed that C-BRIAN-SR was associated with mood/sleep symptoms in healthy controls, which supports that C-BRIAN-SR might be useful to identify individuals with subthreshold mood and sleep disturbances in the early stage of illness. A lower social regularity and/or a higher biological rhythm disturbance have been proposed as a marker for early detection of onset of mood episodes or relapse (Alloy et al. Citation2015; Levenson et al. Citation2015; Shen et al. Citation2008). According to the social rhythm hypothesis of depression, stressful life events interrupt a person’s daily routine or regular exposure to “social zeitgebers” which then lead to instability in specific biological rhythms, such as sleep, in vulnerable individuals (Ehlers et al. Citation1988). It has been demonstrated that alterations in sleep-wake schedules and social cues modify exposure to light, and this change in light exposure serves as the major disruption to the timing of circadian rhythms (Haynes et al. Citation2005). Additionally, patients with a higher degree of social rhythm irregularity often reported a higher level of sleep disturbances (Allega et al. Citation2018; Giglio et al. Citation2009; He et al. Citation2022; Rosa et al. Citation2013). Thirdly, greater biological rhythm disturbance is associated with evening tendency. Similar correlation was found in another study of patients with MDD as well as in patients with extreme evening preference (Kanda et al. Citation2021). Eveningness was associated with greater impulsivity (Evans and Norbury Citation2021), more irregular sleep-wake pattern (Soehner et al. Citation2011), and sleep disturbances (Chan et al. Citation2014); all of these can contribute to both biological rhythm irregularity and depressive symptoms. The bidirectional relationship between mood and biological rhythms, with possible mediation through light exposure, sleep-wake disturbances, and eveningness, may indicate the potential of predicting mood disturbance using multi-modal rhythm assessments. Although BRIAN is a questionnaire-based instrument, it has been shown to correlate with actigraphic wake after sleep onset, total activity count during sleep, and urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin (Allega et al. Citation2018), and has the potential to be used complementarily with objective measures to detect early biological rhythm disruptions.

Association of BRIAN with mood state

All patients recruited in our study were in acute depressive episode; their C-BRIAN-SR score (46.9 ± 6.1) was comparable with other studies conducted in patients with current depressive symptoms (Ozcelik and Sahbaz Citation2020; Palagini et al. Citation2019; Pinho et al. Citation2016), which reported an association between higher level of depressive symptoms with a more severe rhythm disturbance. The mean C-BRIAN-SR score in our study among the depressive patients was higher than some other validation studies of BRIAN conducted in patients with mood disorders in remitted state (Dopierala et al. Citation2016; Iyer and Palaniappan Citation2017; Katram and Kumar Citation2016; Vangal et al. Citation2022). A dose-dependent relationship has been reported in a study of 260 patients with bipolar disorder, with the greatest biological rhythm disturbance found among the depressed patients, followed by patients with subsyndromal symptoms, euthymic patients, and healthy controls (Pinho et al. Citation2016). There is a limited study that focused on remitted MDD patients. However, it was found that the improvement of depressive symptoms is positively associated with the regularization of the biological rhythm (r = 0.594) in a study that reported the change of BRIAN before and after psychological treatment in patients with depressive disorder, although this study did not compare with a control group (Mondin et al. Citation2014). Our study provided further longitudinal and prospective evidence that BRIAN score significantly improved in patients who achieved remission of depression, and the BRIAN score among remitted patients no longer differed from controls. Importantly, a restoration of the biological rhythm regularity was only demonstrated among the patients who achieved remission, despite all of the patients in this study being hospitalized in the psychiatric unit where structure daily routines (including meals time, activity, and light out time) were enforced, indicating that the improvement in biological rhythm could not be solely attributed to the environment. The normalization of C-BRIAN-SR along with depression remission observed in our study was inconsistent to other studies in remitted BD patients who reported a higher BRIAN score when compared to healthy controls (Kuppili et al. Citation2018; Rosa et al. Citation2013). It may be related to the relatively small number of remitted BD patients in our study (7 out of 36). A community study that included both BD and MDD patients actually found biological rhythm disruption in subjects with BD during euthymic status, but not in remitted MDD (Duarte Faria et al. Citation2015). It has been suggested that circadian disruptions are more conspicuous in BD than MDD patients, and that patients with depression and bipolar disorder have commonalities but also distinct differences in their genetic correlations with biological rhythms (Sirignano et al. Citation2022), and further longitudinal research in patients with mood disorder is needed.

Role of social rhythm in treatment of mood disorder

Social rhythm therapy (SRT) which encourages individuals with dysregulated mood to develop and maintain moderately active and consistent daily routines was proposed as a treatment for BD (Frank Citation2007). Cudney et al. found that disruptions in biological rhythms are associated with poor quality of life in BD, independent of sleep disturbance, sleep medication use, and severity of depression; and suggested that regulation of biological rhythms, such as sleep/wake cycles, eating patterns, activities, and social rhythms, may improve QOL in this population (Cudney et al. Citation2016). However, the efficacy regarding the interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) in BD patients was mixed (Hoberg et al. Citation2013; Inder et al. Citation2015; Steardo et al. Citation2020; Swartz et al. Citation2012). This inconsistent result may be attributed to the heterogeneity of BD. In this regard, the C-BRIAN could be investigated as a screening tool to identify susceptible individuals for IPSRT to obtain optimal efficacy. Apart from social rhythm, light signal is the most important environment time cue for circadian entrainment, and light therapy is a widely used treatment strategy in improving sleep and cognitive function, as well as regulating mood and circadian rhythms (Stephenson et al. Citation2012). It is evidenced to be effective and efficient in reducing the intensity of depressive symptoms both as a monotherapy and as an adjunctive treatment (Chan et al. Citation2022, Citation2022; Loving et al. Citation2002; Maruani and Geoffroy Citation2019; Perera et al. Citation2016). It is increasingly recognized that aberrant light exposure could contribute to both biological rhythm and mood disturbance (Blume et al. Citation2019; Dollish et al. Citation2023). In company with previous research in examining patients with mood disorders, our data also supported the need to implement chronotherapeutic strategies targeting social rhythm, light exposure, and sleep-wake disturbances, in the clinical management of depression (Geoffroy and Palagini Citation2021). Future studies shall examine the effects of combination of light therapy and social rhythm therapy in regularization of biological rhythm and treatment of mood disorders.

Limitations

Our study examined the psychometric properties of C-BRAIN-SR in both MDE patients and controls with prospective follow-up. Several limitations should be noted. First, C-BRIAN-SR is a self-administered instrument and is subjected to recall bias, and we did not have objective assessment of the sleep-activity rhythms such as actigraphy. However, C-BRIAN-SR is a convenient measure that can be administered within a clinic consultation setting without prior need to wear the device for days and prior research has demonstrated a correlation of BRIAN with actigraphic parameters and urinary 6-sulfatoxymelatonin levels. In addition, BRIAN also covers additional areas such as social and diet regularity which are not captured by actigraphy. Secondly, we were not able to conclude if there is a causal relationship between biological rhythms disturbances and depression with the current design, as most of the MDE subjects were treated with medications during hospitalization which may modulate the sleep-wake activity.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Traditional Chinese self-report version of the Biological Rhythms Interview for Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (C-BRIAN-SR) is a valid and reliable instrument for measuring rhythm regularity. Our results demonstrated a significantly greater C-BRIAN-SR score in MDE patients when compared to controls and to patients with remission of depression. This scale could be a potentially valuable clinical instrument to identify subjects with greater social rhythm irregularity and to personalize chronological treatment or social rhythm therapy for patients. Additional research may evaluate its role in predicting onset and relapse of affective disorders, and to monitor treatment response as an integral assessment of depression.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (229.4 KB)Disclosure statement

YKW received consultation fee from Eisai Co., Ltd., honorarium from Eisai Hong Kong for lecture, travel support from Lundbeck HK limited for overseas conference, and honorarium from Aculys Pharma, Inc for lecture. JWYC received personal fee from Eisai Co., Ltd and travel support from Lundbeck HK limited for overseas conference. Both are outside the submitted work. None of the authors reports any conflict of interest as related to the study.

Data availability statement

Data is available upon reasonable request made to the corresponding author.

Supplementary data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/07420528.2024.2373215.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allega OR, Leng X, Vaccarino A, Skelly M, Lanzini M, Hidalgo MP, Soares CN, Kennedy SH, Frey BN. 2018. Performance of the biological rhythms interview for assessment in neuropsychiatry: An item response theory and actigraphy analysis. J Affect Disord. 225:54–63. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2017.07.047.

- Alloy LB, Boland EM, Ng TH, Whitehouse WG, Abramson LY. 2015. Low social rhythm regularity predicts first onset of bipolar spectrum disorders among at-risk individuals with reward hypersensitivity. J Abnorm Psychol. 124:944. doi: 10.1037/abn0000107.

- Aschoff J, Fatranska M, Giedke H, Doerr P, Stamm D, Wisser H. 1971. Human circadian rhythms in continuous darkness: entrainment by social cues. Science. 171:213–215. doi: 10.1126/science.171.3967.213.

- Ashman SB, Monk TH, Kupfer DJ, Clark CH, Myers FS, Frank E, Leibenluft E. 1999. Relationship between social rhythms and mood in patients with rapid cycling bipolar disorder. Psychiatry Res. 86:1–8. doi: 10.1016/S0165-1781(99)00019-0.

- Bastien CH, Vallieres A, Morin CM. 2001. Validation of the insomnia severity index as an outcome measure for insomnia research. Sleep Med. 2:297–307. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9457(00)00065-4.

- Blume C, Garbazza C, Spitschan M. 2019. Effects of light on human circadian rhythms, sleep and mood. Somnologie (Berl). 23:147–156. doi: 10.1007/s11818-019-00215-x.

- Boland EM, Bender RE, Alloy LB, Conner BT, Labelle DR, Abramson LY. 2012. Life events and social rhythms in bipolar spectrum disorders: an examination of social rhythm sensitivity. J Affect Disord. 139:264–272. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.01.038.

- Brown LF, Reynolds CF 3rd, Monk TH, Prigerson HG, Dew MA, Houck PR, Mazumdar S, Buysse DJ, Hoch CC, Kupfer DJ. 1996. Social rhythm stability following late-life spousal bereavement: associations with depression and sleep impairment. Psychiatry Res. 62:161–169. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(96)02914-9.

- Bullock B, Judd F, Murray G. 2011. Social rhythms and vulnerability to bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 135:384–388. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.06.006.

- Chan JW, Lam SP, Li SX, Chau SW, Chan SY, Chan NY, Zhang JH, Wing YK. 2020. Adjunctive bright light treatment with gradual advance in unipolar major depressive disorder with evening chronotype – a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 52:1–10. doi: 10.1017/s0033291720003232.

- Chan JW, Lam SP, Li SX, Chau SW, Chan SY, Chan NY, Zhang JH, Wing YK. 2022. Adjunctive bright light treatment with gradual advance in unipolar major depressive disorder with evening chronotype - a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. 52:1448–1457. doi: 10.1017/S0033291720003232.

- Chan JW, Lam SP, Li SX, Yu MW, Chan NY, Zhang J, Wing YK. 2014. Eveningness and insomnia: independent risk factors of nonremission in major depressive disorder. Sleep. 37:911–917. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3658.

- Chan JWY, Chan NY, Li SX, Lam SP, Chau SWH, Liu Y, Zhang J, Wing YK. 2022. Change in circadian preference predicts sustained treatment outcomes in patients with unipolar depression and evening preference. J Clin Sleep Med. 18:523–531. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.9648.

- Cho CH, Jung SY, Kapczinski F, Rosa AR, Lee HJ. 2018. Validation of the Korean version of the biological rhythms interview of assessment in neuropsychiatry. Psychiatry Investig. 15:1115. doi: 10.30773/pi.2018.10.21.1.

- Cudney LE, Frey BN, Streiner DL, Minuzzi L, Sassi RB. 2016. Biological rhythms are independently associated with quality of life in bipolar disorder. Int J Bipolar Disord. 4:9. doi: 10.1186/s40345-016-0050-8.

- Dollish H, Tsyglakova M, McClung C. 2023. Circadian rhythms and mood disorders: time to see the light. Neuron. 112:25–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2023.09.023.

- Dopierala E, Chrobak A, Kapczinski F, Michalak M, Tereszko A, Ferensztajn-Rochowiak E, Dudek D, Jaracz J, Siwek M, Rybakowski JK. 2016. A study of biological rhythm disturbances in polish remitted bipolar patients using the BRIAN, CSM, and SWPAQ scales. Neuropsychobiology. 74:125–130. doi: 10.1159/000458527.

- Duarte Faria A, Cardoso Tde A, Campos Mondin T, Souza LD, Magalhaes PV, Patrick Zeni C, Silva RA, Kapczinski F, Jansen K. 2015. Biological rhythms in bipolar and depressive disorders: a community study with drug-naive young adults. J Affect Disord. 186:145–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2015.07.004.

- Ehlers CL, Frank E, Kupfer DJ. 1988. Social zeitgebers and biological rhythms. A unified approach to understanding the etiology of depression. Archiv Gener Psychiatry. 45:948–952. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1988.01800340076012.

- Evans SL, Norbury R. 2021. Associations between diurnal preference, impulsivity and substance use in a young-adult student sample. Chronobiol Int. 38:79–89. doi: 10.1080/07420528.2020.1810063.

- Frank E. 2007. Interpersonal and social rhythm therapy: a means of improving depression and preventing relapse in bipolar disorder. J Clin Psychol. 63:463–473. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20371.

- Geoffroy PA, Palagini L. 2021. Biological rhythms and chronotherapeutics in depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 106:110158. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2020.110158.

- Giglio LM, Magalhaes PV, Andreazza AC, Walz JC, Jakobson L, Rucci P, Rosa AR, Hidalgo MP, Vieta E, Kapczinski F. 2009. Development and use of a biological rhythm interview. J Affect Disord. 118:161–165. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.018.

- Haynes PL, Ancoli-Israel S, McQuaid J. 2005. Illuminating the impact of habitual behaviors in depression. Chronobiol Int. 22:279–297. doi: 10.1081/CBI-200053546.

- He S, Ding L, He K, Zheng B, Liu D, Zhang M, Yang Y, Mo Y, Li H, Cai Y, et al. 2022. Reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the biological rhythms interview of assessment in neuropsychiatry in patients with major depressive disorder. BMC Psychiatry. 22:834. doi: 10.1186/s12888-022-04487-w.

- Hoberg AA, Ponto J, Nelson PJ, Frye MA. 2013. Group interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for bipolar depression. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 49:226–234. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12008.

- Horne JA, Ostberg O. 1976. A self-assessment questionnaire to determine morningness-eveningness in human circadian rhythms. Int J Chronobiol. 4:97–110. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1027738.

- Inder ML, Crowe MT, Luty SE, Carter JD, Moor S, Frampton CM, Joyce PR. 2015. Randomized, controlled trial of interpersonal and social rhythm therapy for young people with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 17:128–138. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12273.

- Iyer A, Palaniappan P. 2017. Biological dysrhythm in remitted bipolar I disorder. Asian J Psychiatr. 30:218–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2017.05.012.

- Kanda Y, Takaesu Y, Kobayashi M, Komada Y, Futenma K, Okajima I, Watanabe K, Inoue Y. 2021. Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the biological rhythms interview of assessment in neuropsychiatry-self report for delayed sleep-wake phase disorder. Sleep Med. 81:288–293. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2021.02.009.

- Katram B, Kumar CS. 2016. Biological rhythm disturbances in patients with bipolar disorder under remission. Telangana J Psychiatry. 2:76–79. doi: 10.4103/2455-8559.314838.

- Kuppili PP, Menon V, Chandrasekaran V, Navin K. 2018. Biological rhythm impairment in bipolar disorder: a state or trait marker? Indian J Psychiatry. 60:404–409. doi: 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_110_18.

- Leung CM, Wing YK, Kwong PK, Lo A, Shum K. 1999. Validation of the Chinese-Cantonese version of the hospital anxiety and depression scale and comparison with the Hamilton rating scale of depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 100:456–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1999.tb10897.x.

- Levenson JC, Wallace ML, Anderson BP, Kupfer DJ, Frank E. 2015. Social rhythm disrupting events increase the risk of recurrence among individuals with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 17:869–879. doi: 10.1111/bdi.12351.

- Loving RT, Kripke DF, Shuchter SR. 2002. Bright light augments antidepressant effects of medication and wake therapy. Depress Anxiety. 16:1–3. doi: 10.1002/da.10036.

- Maruani J, Geoffroy PA. 2019. Bright light as a personalized precision treatment of mood disorders. Front Psychiatry. 10:85. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00085.

- Meyrel M, Scott J, Etain B. 2022. Chronotypes and circadian rest–activity rhythms in bipolar disorders: A meta-analysis of self- and observer rating scales. Bipolar Disord. 24:286–297. doi: 10.1111/bdi.13122.

- Mistlberger RE, Skene DJ. 2005. Nonphotic entrainment in humans? J Biol Rhythms. 20:339–352. doi: 10.1177/0748730405277982.

- Mondin TC, de Azevedo Cardoso T, Jansen K, Coiro Spessato B, de Mattos Souza LD, da Silva RA. 2014. Effects of cognitive psychotherapy on the biological rhythm of patients with depression. J Affect Disord. 155:142–148. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2013.10.039.

- Monk TH, Flaherty JF, Frank E, Hoskinson K, Kupfer DJ. 1990. The social rhythm metric. An instrument to quantify the daily rhythms of life. J Nerv Ment Dis. 178:120–126. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199002000-00007.

- Monk TH, Kupfer DJ, Frank E, Ritenour AM. 1991. The social rhythm metric (SRM): Measuring daily social rhythms over 12 weeks. Psychiatry Res. 36:195–207. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(91)90131-8.

- Moro MF, Carta MG, Pintus M, Pintus E, Melis R, Kapczinski F, Vieta E, Colom F. 2014. Validation of the Italian version of the biological rhythms interview of assessment in neuropsychiatry (BRIAN): some considerations on its screening usefulness. Clin Pract Epidemiol Ment Health. 10:48–52. doi: 10.2174/1745017901410010048.

- Mukaka MM. 2012. Statistics corner: A guide to appropriate use of correlation coefficient in medical research. Malawi Med J. 24:69–71. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23638278

- Ozcelik M, Sahbaz C. 2020. Clinical evaluation of biological rhythm domains in patients with major depression. Braz J Psychiatry. 42:258–263. doi: 10.1590/1516-4446-2019-0570.

- Palagini L, Cipollone G, Moretto U, Masci I, Tripodi B, Caruso D, Perugi G. 2019. Chronobiological dis-rhythmicity is related to emotion dysregulation and suicidality in depressive bipolar II disorder with mixed features. Psychiatry Res. 271:272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.11.056.

- Perera S, Eisen R, Bhatt M, Bhatnagar N, de Souza R, Thabane L, Samaan Z. 2016. Light therapy for non-seasonal depression: Systematic review and meta-analysis. BJPsych Open. 2:116–126. doi: 10.1192/bjpo.bp.115.001610.

- Pinho M, Sehmbi M, Cudney LE, Kauer-Sant’anna M, Magalhaes PV, Reinares M, Bonnin CM, Sassi RB, Kapczinski F, Colom F, et al. 2016. The association between biological rhythms, depression, and functioning in bipolar disorder: a large multi-center study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 133:102–108. doi: 10.1111/acps.12442.

- Rosa AR, Comes M, Torrent C, Sole B, Reinares M, Pachiarotti I, Salamero M, Kapczinski F, Colom F, Vieta E. 2013. Biological rhythm disturbance in remitted bipolar patients. Int J Bipolar Disord. 1:6. doi: 10.1186/2194-7511-1-6.

- Sabet SM, Dautovich ND, Dzierzewski JM. 2021. The rhythm is gonna get you: Social rhythms, sleep, depressive, and anxiety symptoms. J Affect Disord. 286:197–203. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.02.061.

- Shen GH, Alloy LB, Abramson LY, Sylvia LG. 2008. Social rhythm regularity and the onset of affective episodes in bipolar spectrum individuals. Bipolar Disord. 10:520–529. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00583.x.

- Sirignano L, Streit F, Frank J, Zillich L, Witt SH, Rietschel M, Foo JC. 2022. Depression and bipolar disorder subtypes differ in their genetic correlations with biological rhythms. Sci Rep. 12:15740. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-19720-5.

- Soehner AM, Kennedy KS, Monk TH. 2011. Circadian preference and sleep-wake regularity: Associations with self-report sleep parameters in daytime-working adults. Chronobiol Int. 28:802–809. doi: 10.3109/07420528.2011.613137.

- Steardo L Jr., Luciano M, Sampogna G, Zinno F, Saviano P, Staltari F, Segura Garcia C, De Fazio P, Fiorillo A. 2020. Efficacy of the interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT) in patients with bipolar disorder: Results from a real-world, controlled trial. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 19:15. doi: 10.1186/s12991-020-00266-7.

- Stephenson KM, Schroder CM, Bertschy G, Bourgin P. 2012. Complex interaction of circadian and non-circadian effects of light on mood: shedding new light on an old story. Sleep Med Rev. 16:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.09.002.

- Swartz HA, Frank E, Cheng Y. 2012. A randomized pilot study of psychotherapy and quetiapine for the acute treatment of bipolar II depression. Bipolar Disord. 14:211–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2012.00988.x.

- Szuba MP, Yager A, Guze BH, Allen EM, Baxter LR Jr. 1992. Disruption of social circadian rhythms in major depression: a preliminary report. Psychiatry Res. 42:221–230. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(92)90114-I.

- Vangal KK, Soman S, Bhandaryp R, Praharaj SK. 2022. Biological rhythms and quality of life in remitted bipolar disorder patients in comparison with normal controls: a cross-sectional study. Minerva Psychiatry. 63:245–253. doi: 10.23736/S2724-6612.21.02162-2.

- Williams JB, Link MJM, Rosenthal NE, Amira L, Terman M. 1994. Structured interview guide for the Hamilton depression rating scale, seasonal affective disorders version (SIGHSAD). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute.

- Yu DS. 2010. Insomnia severity index: psychometric properties with Chinese community-dwelling older people. J Adv Nurs. 66:2350–2359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2010.05394.x

- Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. 1983. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 67:361–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x.

Appendix A.

Biological Rythm Interview of Assessment in Neuropsychiatry (BRIAN)

生理節律訪談 腦神經精神病學評估

從以下的選項, 請選擇一個最能形容你過去十五天內的行為:

睡眠 Sleep

1. 你在慣常的時間入睡有沒有困難?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

2. 你在慣常的時間醒來有沒有困難?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

3. 你醒來後起床有沒有困難?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

4. 以你慣常的睡眠時間, 你是否有困難達到足夠的休息(包括主觀感覺和實際的表現,如駕駛、工作)?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

5. 你有否在想要休息時難以完全靜止下來(「熄機」)?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

活動 Activity

6. 你在完成工作上有困難嗎?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

7. 你在完成家務上有困難嗎?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

8. 你是否難以保持慣常作體力活動(例如乘搭公共汽車、地鐵或運動)的規律?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

9. 你是否難以如期進行日常的活動?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

10. 你是否難以維持慣常的性需要或性行為?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

社交 Social interaction

11. 你是否難以與重要的人溝通和建立(人際)關係?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

12. 你是否過度使用電子產品(如電視或互聯網),以致損害你的人際關係?如有,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

13. 你是否難以保持你的日常規律和作息時間與其他重要的人(例如:家人, 朋友, 配偶)同步?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

14. 你是否難以給予其他重要的人(例如:家人, 朋友, 配偶)你的關注?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

飲食習慣 Dietary habit

15. 你是否難以按時用餐?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

16. 你有否不吃正餐?如有的話,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

17. 你是否難以保持固定食量?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

18. 你是否有困難去維持使用適量的提神產品(如咖啡、可樂和巧克力)?如有困難,有多頻密?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

主導節律(「時型 」) Predominant rhythm (Chronotype)

請根據你過去 12 個月的情況回答以下問題

19. 在晚間, 你在工作上和人際關係上都更有活力

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

20. 在早上, 你的工作能力更高

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

21. 你有日夜顛倒的情況嗎?

(1) 一點也不

(2) 很少

(3) 有時

(4) 經常

Translated by Dr. Joey WY Chan, Dr. Steven WH Chau, Dr. NY Chan, Ms. Xie Chen, Prof. YK Wing. Department of Psychiatry, The Chinese University of Hong Kong 2021. Permission was obtained from Prof. Flávio Kapczinski, Professor of Psychiatry, Director - Graduate Program in Neuroscience. St. Joseph’s Healthcare Hamilton McMaster University.