Abstract

Fear of childbirth (FOC) can lead to maternal distress during and after pregnancy. The aim of this randomized controlled trial (RCT) was to examine whether art therapy as an adjunct to midwife-led counseling (study group) could reduce FOC significantly more than midwife-led counseling alone (control group). The on-treatment analysis included 82 women assessed by the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire (W-DEQ) at pre- and post-timepoints. Both treatments resulted in significantly reduced FOC and there was no significant difference between the two groups. Art therapy may be used as a tailored intervention for those women who are interested in the treatment but further research is warranted.

Fear of childbirth (FOC), also referred to as tokophobia, is related to feelings of limited capability in the face of childbirth and affects the pregnant woman’s quality of life. It is more common in nulliparous women but can also be related to earlier traumatic birth experiences (O’Connell, Leahy-Warren, Khashan, Kenny, & O’Neill, Citation2017). The prevalence of FOC varies between 5.5 and 26.2%, depending on definition and cutoff points in different studies using the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire (W-DEQ) instrument (Wijma, Wijma, & Zar, 1998). A meta-analysis has estimated the global pooled prevalence rate of FOC as 14% (O’Connell et al., Citation2017).

Tokophobia is classified as an anxiety disorder that has been reported in many high-income countries and recent research from Europe has attempted to identify causes of FOC (Demsar et al., Citation2018; Sioma-Markowska, Żur, Skrzypulec-Plinta, Machura, & Czajkowska, Citation2017). Symptoms include tension, anxiety, depression, distressing thoughts, and stress (Rondung, Thomten, & Sundin, Citation2016). FOC was related to perceived threats to both the pregnant woman and her child. The most common explanations reported were fear of the pain of labor, anxieties about the health of the child, anxiety about the possibility of childbirth complications and about the loss of control. It seems that women with experience of sexual abuse and traumatic experience of former birth are more susceptible to FOC (Demsar et al., Citation2018). Research has shown that pregnant women with a pronounced FOC run significantly higher risks of birth complications with resulting psychological trauma than women without a pronounced FOC (Alehagen, Wijma, & Wijma, Citation2006). It is associated with a higher frequency of induction of labor and elective cesarean section, increased levels of stress hormones, negative childbirth experiences, post-traumatic stress, and difficulties in an attachment to the newborn (Ayers, Citation2014).

Treatments aimed at alleviating fear may minimize adverse outcomes associated with severe FOC. However, the evidence base for FOC treatments is not strong. A systematic review (Striebich, Mattern, & Ayerle, Citation2018) included 19 articles on the effects of interventions for women with FOC and showed that psycho-educative phone calls significantly reduced FOC and increased self-efficacy and a therapist-supported program based on cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) was also beneficial. Moreover, women benefitted from psycho-education in groups (Nieminen, Andersson, Wijma, Ryding, & Wijma, Citation2016; Rouhe et al., Citation2013; Striebich et al., Citation2018). In Sweden, obstetric units offer specialist treatment using midwife-led counseling and birth planning for women with severe FOC although supplementary education for midwives who provide this counseling and the availability of treatment options vary at different clinics (Larsson, Karlstrom, Rubertsson, & Hildingsson, Citation2016).

Art therapy (AT) offers promise for treating FOC, but it has not been investigated. AT is a creative form of psychotherapy treatment that may be used to treat severe cases of psychic disability, trauma and crisis reaction (Schouten, de Niet, Knipscheer, Kleber, & Hutschemaekers, Citation2015). Traumatic emotional experiences or memories of trauma can often be difficult to verbalize. AT provides a possibility to express these feelings in a way that, for the individual, surpasses the spoken or written word. Creating visual images stimulates activity in the area of the brain where visual memories are stored (Gantt & Tinnin, Citation2009). The use of images as a tool removes the client and the therapist from the traditional therapeutic environment. The image becomes a window that is available for both the client and the therapist (Schaverien, Citation1999) but can also be seen as a transition object (Winnicott, Citation1989) where the client’s emotions and experiences are retained with the help of color and form. The therapy process becomes visual and concrete, giving the client the possibility to return to earlier stages in the process.

A literature review (Hogan, Sheffield, & Woodward, Citation2017) on AT in antenatal and postnatal care identified several studies regarding postnatal depression and birth trauma. Results showed a small evidence-base pointing to the usefulness of AT in the transition to motherhood. To our knowledge, Wahlbeck, Kvist, and Landgren (Citation2018) conducted the first peer-reviewed study on AT for severe FOC. This qualitative study of 19 women who received five sessions of AT as a complement to midwife-led counseling were interviewed 3 months after birth. The semi-structured interviews which were rich in-depth and breadth were analyzed with a phenomenological hermeneutical method. Although several women described their feelings as carrying heavy baggage, results showed that through the use of images and colors, the women could access difficult emotions. When fear, for example of being torn apart during the birth, was deposited in the images, the women were relieved. The women described feelings of loneliness in their fear. Painting offered a catalyst for the healing process by helping them visualize their fear and communicate it to their midwife, partner, and members of the AT group. AT was well accepted by the women, who gained hope and self-confidence. AT gave room for reflection and women attained a new, more positive perspective. When they could imagine themselves with the baby in their arms they identified themselves as mothers, and the expected child became real, allowing the bonding process to start. The images became treasured items, reminding the women about the process they underwent during the AT.

The aim of the present study was to examine whether women treated with AT as an adjunct to midwife-led counseling more often showed reduced FOC than women treated by midwife-led counseling alone. Our hypothesis was that treatment by midwife-led counseling (MC) combined with AT would result in a reduction in the level of FOC in statistically significantly more women than MC alone. The quantitative study is a complement to a formerly published qualitative study (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018).

Methods

Research Design

The study was carried out as an open, randomized, controlled trial with two arms to compare treatment alternatives for severe FOC. Following recommendations for RCTs of the efficacy of AT (Hogan et al., Citation2017), qualitative and quantitative methods were used in two separate studies. This paper only reports on the quantitative findings. The qualitative results from 19 participants were published elsewhere (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). Ethical clearance for the study was granted by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund, Sweden; number 2010/422. The trial was registered in 2011 at ClinicalTrials.gov and given the register number:10/19/2011.

Participants

A sample size calculation (α = 0.05, β = 0.2) showed a requirement of 128 study participants (64 × 2). Participants were recruited between March 2011 and March 2017 from 10 antenatal clinics in southern Sweden. At these clinics, all women who register their pregnancy are asked to indicate, on a visual analog scale, the extent of their fear of the approaching birth. The scale ranges from “0 = No fear of the birth” to “10 = Extremely fearful of the birth.” Scores above 7 are considered high enough to require treatment and these women are referred to a specialist group at the obstetric unit at the regional hospital. When contact was made with the specialist group, these women were invited to join the present study. Statistics from the unit (unpublished) show that 4.3% of pregnant women were referred to the specialist group because of severe FOC during the data collection period. Pregnant women who did not understand or speak Swedish, had physical hindrance for a vaginal birth or were diagnosed with obstetrical complications, a current depression requiring medical intervention, acute psychosis or current substance abuse were excluded from the study. Women who registered later than the 35th gestational week were also excluded since there was a risk that the treatment could not be finished before the birth.

Measures

The W-DEQ questionnaire has 33 statements about expectations and experiences before birth, some formulated as positive statements and some as negative statements. The statements are answered on 6-point Likert scales requiring the woman to envisage how labor and birth will be and how they expect to feel. Possible total scores range from 0 to 165; the higher the score, the more fearful the woman is. For this reason, positively phrased statements are reverse-scored. In a Swedish study of 1,635 unselected women, a W-DEQ score of between 85 and 99 was considered as high FOC and those with a score of 100 or more were in severe fear of childbirth (Nieminen, Stephansson, & Ryding, Citation2009). These cutoff points were used in the present study; since the women in this study were a selected cohort with self-reported FOC, it was expected that their W-DEQ scores would be high at recruitment.

Procedures

The women were given written and oral information and informed of their right to leave the study whenever they wished, with no detriment to their care. Those who agreed to take part in the study were asked to complete a consent form agreeing that the study manager was allowed to extract information about the birth and postpartum period from the participant’s obstetric journal. At this point, the women were also asked to complete the initial W-DEQ and answer questions regarding their age, parity, civil status, and the highest level of education. Their general state of health was measured on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from very poor (1) to very good (5).

When the questionnaires were completed, randomization was carried out via a computer-generated randomization chart and the individual was informed whether she had been randomized to the control group (CG) or the study group (SG). There is a difference in parity in studies of fear of childbirth, showing that approximately 16% of nulliparous and 12% of multiparous women are affected (O’Connell et al., Citation2017). Therefore, randomization was preceded by stratification according to parity, which resulted in equal division between primiparous and multiparous women.

Both the control group (CG) and study group (SG) were treated using MC, which is the standard care for women with FOC at the clinic in southern Sweden where the study took place. The study group was also treated by AT as an adjunct to MC. Women who were randomized to the SG were contacted by the art therapist within 1 week, in order to schedule the first session. At the same time, a request for consultation was sent to the specialist group at the hospital who summonsed the women to commence MC. Both interventions are further described below. The post W-DEQ was provided after the last therapy appointment (either AT or counseling), which was approximately 1 month before the estimated date of birth. At the time of the second questionnaire, the women were asked how many sessions of midwife-led counseling they attended and whether they had used any other forms of treatment for their FOC.

MC

The specialist team at the obstetric unit consists of five midwives and an obstetrician. The aims of MC at the clinic are to reduce FOC in a multifaceted manner: (1) provide increased sense of security for the impending birth, (2) encourage more women with FOC to give vaginal birth, (3) afford each woman a positive experience of birth (irrespective of type of birth) increase security for those with previous difficult or traumatic birth experiences, (4) increase women’s knowledge about their body and the process of birth, (5) increase feelings of personal control and improve knowledge about FOC, and (6) work toward reduced stigmatization.

The sessions of MC provided at the unit are not based on a manual; instead, each midwife assesses the needs of the individual woman. Initially, each woman has a one-to-one meeting with a midwife from the specialist team. For multiparous women, the midwife and woman examine case notes from previous birth(s) together and the woman is asked about her experiences of what is written in the case notes. Any uncertainties about what occurred are discussed and explanations provided where possible. If the woman is not familiar with the birthing environment a visit to the birthing unit is suggested. In the majority of cases, the woman and midwife draw up a plan for the approaching birth together. Continued sessions are based on the woman’s individual and personally expressed needs. The partner is invited to one of the sessions. According to national guidelines, an obstetrician can be asked to join the discussion when a woman expresses a wish for a planned induction or cesarean section (Nationella Medicinska Indikationer, Citation2011).

Intervention by AT

Women in the SG were invited to five AT sessions. The aims were to reduce FOC and motivate more women to give vaginal birth. When only one participant was recruited, AT was provided individually. When more than one was recruited participants could choose individual or group AT. A group was limited to three participants. Twenty-seven women were treated individually and 12 in the group. The sessions were given between 28 and 36 gestational weeks and held in a locality outside of the hospital surroundings.

The painting was offered as a tool for self-reflection to release feelings they were unable to express elsewhere, to strengthen the process of bonding with their baby, and to initiate the counseling component of AT. The participants used paper, watercolors, pastel crayons, sponges, and paintbrushes working on an easel. The sessions were given once per week and lasted between 90 and 120 min. The art therapist was a midwife and first author in this study.

The women were given an introduction to the process of AT and assured that they were the owners of everything they created: nothing would be collected and the use of materials would only be with the full approval of the individual. Each session began with 10 min guided relaxation with a focus on breathing and body awareness. The art therapist provided a theme for each session to be used as a structural framework. In order to ease the participants into the creation of images, the first session started with a general theme: “Paint a tree” followed by “Paint the baby,” At the second session themes connected to the approaching birth were introduced: “Mind and body mapping,” “Paint your own body,” and “Worry and fear.” The theme for the third session was “The birthing room,” allowing the participants to approach difficult scenarios concretely. At the fourth session, the women painted their goals based on the themes “Where am I going?” “How can I get through this?” and “What is hindering me?” with the intention of helping the women to find their own goal picture to bear with them on the journey toward birth. In the fifth session, they painted a final image to conclude their birth preparation process.

During the creation of images, the art therapist communicated with each woman about the work in progress and in the case of group activity, the women discussed their creations amongst themselves. It was suggested that participants stand whilst painting to promote body awareness and enable free movement. While discussing the images, during relaxation and whenever they wanted to the women sat down. At the final session, the therapist once more spoke about the process involved in AT in order to give the women a chance to reflect on their journey.

Validity

This RCT followed CONSORT recommendations and has been registered at ClinicalTrials.gov. The W-DEQ (Wijma et al., Citation1998) has been extensively used in international studies and is generally considered to be a well-validated and reliable tool (Fenwick, Gamble, Nathan, Bayes, & Hauck, Citation2009; Garthus-Niegel, Størksen, Torgersen, Von Soest, & Eberhard-Gran, Citation2011). However, it has recently been criticized by other researchers (Pallant et al., Citation2016). Further validity was established by conducting the study in a real-life environment and the women had contact with the art therapist for at least 1 month. To avoid bias, the results were analyzed together with two researchers not involved in the work at the clinic.

Data Analysis

The primary outcome variable was the number of pregnant women whose FOC decreased from severe (≥100 W-DEQ points) to any level below this (≤99 W-DEQ points) after treatment in SG or CG. Secondary outcome variables were as follows: (1) comparison of changes in the mean W-DEQ between measurements at recruitment and at the end of treatment for SG and CG, (2) comparison of number of MC sessions required by SG and CG, (3) comparison of type of birth; normal vaginal birth versus all other types of birth between SG and CG, and (4) number of women with higher levels of FOC after treatment.

Outcomes were analyzed with the on-treatment technique using SPSS version 25. Comparisons between SG and CG were carried out using Pearson’s Chi-square (χ2) test for nominal variables and after testing for normal distribution student’s t-test was used for continuous variables. Paired samples t-test was used to compare mean total W-DEQ scores between the first and second measurements for both groups. Independent samples t-test was used to compare means for numbers of midwife-led counseling-sessions required by SG and CG participants. All tests were two-sided and a p-value of ≤0.05 was accepted as statistically significant.

Results

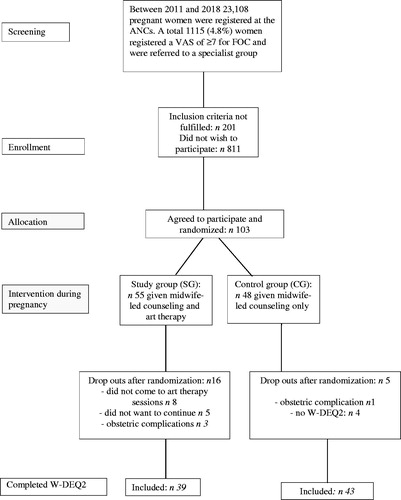

In total 1115 pregnant women were referred to the specialist clinic for FOC between 2011 and 2017. The 904 women who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited to join the trial. A total of 103 (9.2% of those referred) agreed to partake and were randomized. After randomization 21 of these dropped out leaving 82 individuals in the on-treatment analysis: 39 in the study group and 43 in the control group (). shows age, parity, and education level of the women included in the analyses. W-DEQ scores at inclusion in the study ranged from 85 to 185 in the SG and from 88 to 180 in the CG.

Figure 1 Flow Chart (ANC: AnteNatal Clinics; VAS: Visual Analog Scale; FOC: fear of childbirth; n: number; W-DEQ2: the second measurement on the Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire)

Table 1. Background Information on the Study Participants

Primary Outcome

In the SG, 36 of 39 women had W-DEQ scores of ≥100 before treatment and 17 showed a reduction in their scores to ≤99 after treatment. In the CG, 40 of 43 women had W-DEQ scores of ≥100 before treatment and 15 showed a reduction in their scores to ≤99. There was no statistically significant difference between SG and CG for the number of women whose FOC decreased from severe before treatment to any level below this after treatment: χ2 = 0.34 (1df), p = 0.56.

Secondary Outcomes

Both groups showed statistically significant improvement in mean W-DEQ scores after treatment (SG: t-value 10.16, p < 0.01; CG: t-value 7.52, p < 0.01). There was no significant difference between SG and CG for mean W-DEQ scores after treatment (p = 0.89).

The SG required a mean of 2.21 (±1.11) MC-sessions and the CG required a mean of 2.79 (±1.14) MC-sessions, which was a statistically significant difference: t-value −2.30, p = 0.02. A total of four women showed higher W-DEQ scores after the completion of treatment: one in the SG and three in the CG. In the SG, 20 women required additional counseling sessions with other health care professionals compared to 17 women in the CG. This difference was not statistically significant: χ2 = 0.44 (1df), p = 0.50. There was no significant difference between groups when numbers of uncomplicated vaginal birth were compared with all other types of birth (instrumental vaginal birth, emergency and planned cesarean section): χ2 = (1 df), p = 0.06. shows comparisons of the type of birth between SG and CG.

Table 2. Comparison of Mode of Birth Between SG and CG

Discussion

The effect of FOC on pregnant women’s quality of life (Striebich et al., Citation2018) renders interventions to reduce fear very importantly. In the present study, FOC was significantly reduced in both SG and CG between the first and the second measurements. As all participants followed the program that included MC at the specialist clinic for FOC, the positive result might be interpreted as a good effect of MC which is consistent with earlier studies (Christiaens, Van De Velde, & Bracke, Citation2011; Larsson, Hildingsson, Ternström, Rubertsson, & Karlström, Citation2018; Larsson, Karlstrom, Rubertsson, & Hildingsson, Citation2015; Toohill et al., Citation2014). While FOC decreased in both groups, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups for numbers of pregnant women whose FOC decreased from severe to any level below nor was the differences between groups for the mode of birth statistically significant (p = 0.06). These non-significant results may to some extent be explained by the fact that the sample size was not met because the study was ended due to slow recruitment: a total of 82 individuals were included after 6 years of recruitment. For four women in the study (one in SG and three in CG) treatment for FOC was not effective and they showed higher W-DEQ scores after treatment. A possibility here is that these women became more fearful as the birth became imminent.

Practical Implications

It has been suggested that frequent visits to the midwife might decrease anxiety for women with FOC (Hildingsson, Karlstrom, Rubertsson, & Haines, Citation2019). Through sharing their burden of fear, the women could visualize and access difficult emotions, thereby gaining hope and self-confidence. Cognitive factors are essential in overcoming fear so interventions should focus on the development of cognition. MC can help women to process previous birth traumas, offer concrete planning of the impending birth, the promise of adequate pain management and strengthen the woman in her decisions about birth.

Based on these findings, AT should not be viewed as replacement therapy to MC but rather as an adjunctive service to help women whose reproductive health may be seriously affected by FOC. Even though AT was not shown here to be superior to MC, results from the qualitative interviews showed that AT was highly valued (Wahlbeck et al., Citation2018). In that portion of the study, women described how the intense fear had been relieved with AT, making them feel stronger and calmer. The women experienced that the images allowed them to express fear in another way, opening up a therapeutic discussion where they could be deeply understood and confirmed by the midwife/AT. It offered some women a means of improving their self-reliance, self-confidence and self-awareness, and of enhancing the birth process. AT enhances dialogue through the patient-therapist relationship and helps increase emotional expression (Schaverien, Citation1999). The positive outcome in the qualitative study might be related to the fact that the interviews were conducted 3 months after the birth, while data in the present quantitative study were collected before giving birth, in line with other studies (Rondung et al., Citation2018).

Limitations

Difficulties with poor recruitment and noncompliance in RCTs in clinical settings in other studies (Fletcher, Gheorghe, Moore, Wilson, & Damery, Citation2012; Thies-Lagergren, Kvist, Sandin-Bojo, Christensson, & Hildingsson, Citation2013; Tooher, Middleton, & Crowther, Citation2008) also impacted the present study. There were several factors that impacted the inability to meet the sample size. Of the 914 eligible women, only 103 agreed to participate, although it is not known how many of the 914 were informed and invited to partake in the study. These numbers may indicate a modest interest in AT or mirror the fact that structural changes occurred at the antenatal clinics during the recruitment period. Of the 54 women randomized to AT there were eight women who did not turn up at the sessions and five who started but decided not to continue. None of the dropouts were in group treatment. It is possible that the extra time required for AT (five sessions of 1.5 h) was a hindrance for some women to participate. It may also have been difficult for the midwives to accept the idea of a new form of treatment for FOC, resulting in extremely slow recruitment to the study. Lastly, the long recruitment period spanned a re-structuring of maternal services during the study period. Had the sample size been met, it is possible that analyses might have shown different results: one important secondary outcome, type of birth, was close to significance.

Despite RCT protocols, there were instances of missing data. For example, three women in each group did not have scores on the first W-DEQ measurement that indicated severe FOC is a limitation. It was not possible to know this a priori since the W-DEQ measurement was part of the study and not carried out until the woman had given her consent to participate. However, since the numbers of women with less than severe FOC were the same in the two arms, remaining analyses cannot have been compromised.

It has become common at Swedish antenatal clinics to use Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for the identification of women with FOC despite a lack of validation of the instrument for this group. The instrument is simple and easily applied. VAS use has recently been tested in a study of first-time mothers’ birth experiences (Johansson & Finnbogadottir, Citation2019). The fact that six women in the present study did not have W-DEQ scores indicative of severe FOC may be an indication that VAS used for FOC requires further examination.

Although roles as therapist and researcher should ideally not be combined, it is a strength that Wahlbeck, the art therapist, did not have a midwife-patient relationship with any of the participants and that neither Landgren nor Kvist were involved in patient care at the obstetric clinic. Despite these limitations, it may be possible to transfer the findings of this study to pregnant women in similar and even in different socio-cultural settings, but new studies are needed to clarify this point.

Conclusion

Treatment by MC alone or with AT as adjunct significantly reduced women’s fear of childbirth. AT may be used as a tailored intervention for women who are interested in such treatment. An RCT where the sample size is fulfilled might reveal more interesting results.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Helén Wahlbeck

Helén Wahlbeck, RM, RN, art therapist, is a midwife at Najaden Midwifery Clinic, Helsingborg, Sweden

Linda J. Kvist

Linda J. Kvist, PhD, MScN, RM, RN, is an associate professor, and Kajsa Landgren, PhD, RN, PMHN, is an associate professor, both at Health Sciences Center, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

Kajsa Landgren

Linda J. Kvist, PhD, MScN, RM, RN, is an associate professor, and Kajsa Landgren, PhD, RN, PMHN, is an associate professor, both at Health Sciences Center, Faculty of Medicine, Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

References

- Alehagen, S., Wijma, B., & Wijma, K. (2006). Fear of childbirth before, during, and after childbirth. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 85(1), 56–62. doi:10.1080/00016340500334844

- Ayers, S. (2014). Fear of childbirth, postnatal post-traumatic stress disorder and midwifery care. Midwifery, 30(2), 145–148. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2013.12.001

- Christiaens, W., Van De Velde, S., & Bracke, P. (2011). Pregnant women’s fear of childbirth in midwife- and obstetrician-led care in Belgium and the Netherlands: Test of the medicalization hypothesis. Women & Health, 51(3), 220–239. doi:10.1080/03630242.2011.560999

- Demsar, K., Svetina, M., Verdenik, I., Tul, N., Blickstein, I., & Globevnik Velikonja, V. (2018). Tokophobia (fear of childbirth): Prevalence and risk factors. Journal of Perinatal Medicine, 46(2), 151–154. doi:10.1515/jpm-2016-0282

- Fenwick, J., Gamble, J., Nathan, E., Bayes, S., & Hauck, Y. (2009). Pre- and postpartum levels of childbirth fear and the relationship to birth outcomes in a cohort of Australian women. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 18(5), 667–677. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2008.02568.x

- Fletcher, B., Gheorghe, A., Moore, D., Wilson, S., & Damery, S. (2012). Improving the recruitment activity of clinicians in randomised controlled trials: A systematic review. BMJ Open, 2(1), e000496. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2011-000496

- Gantt, L., & Tinnin, L. W. (2009). Support for a neurobiological view of trauma with implications for art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(3), 148–153. doi:doi:10.1016/j.aip.2008.12.005

- Garthus-Niegel, S., Størksen, H. T., Torgersen, L., Von Soest, T., & Eberhard-Gran, M. (2011). The Wijma Delivery Expectancy/Experience Questionnaire—A factor analytic study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 32(3), 160–163.

- Hildingsson, I., Karlstrom, A., Rubertsson, C., & Haines, H. (2019). Women with fear of childbirth might benefit from having a known midwife during labour. Women and Birth, 32(1), 58–63. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.014

- Hogan, S., Sheffield, D., & Woodward, A. (2017). The value of art therapy in antenatal and postnatal care: A brief literature review with recommendations for future research. International Journal of Art Therapy, 22(4), 169–179. doi:10.1080/17454832.2017.1299774

- Johansson, C., & Finnbogadottir, H. (2019). First-time mothers’ satisfaction with their birth experience - a cross-sectional study. Midwifery, 79, 102540. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2019.102540

- Larsson, B., Hildingsson, I., Ternström, E., Rubertsson, C., & Karlström, A. (2018). Women’s experience of midwife-led counselling and its influence on childbirth fear: A qualitative study. Women and Birth, 32(1), e88–e94. doi:doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2018.04.008

- Larsson, B., Karlstrom, A., Rubertsson, C., & Hildingsson, I. (2015). The effects of counseling on fear of childbirth. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 94(6), 629–636. doi:10.1111/aogs.12634

- Larsson, B., Karlstrom, A., Rubertsson, C., & Hildingsson, I. (2016). Counseling for childbirth fear - a national survey. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare, 8, 82–87. doi:10.1016/j.srhc.2016.02.008

- Nationella Medicinska Indikationer. (2011). Indikationer för kejsarsnitt på moderns önskan [Indication for Caesarean section on mother’s wish] (Report 09). Retrieved from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/globalassets/sharepoint-dokument/dokument-webb/ovrigt/nationella-indikationer-kejsarsnitt-moderns-onskan.pdf

- Nieminen, K., Andersson, G., Wijma, B., Ryding, E. L., & Wijma, K. (2016). Treatment of nulliparous women with severe fear of childbirth via the Internet: A feasibility study. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 37(2), 37–43. doi:10.3109/0167482X.2016.1140143

- Nieminen, K., Stephansson, O., & Ryding, E. L. (2009). Women’s fear of childbirth and preference for cesarean section–a cross-sectional study at various stages of pregnancy in Sweden. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 88(7), 807–813. doi:10.1080/00016340902998436

- O’Connell, M. A., Leahy-Warren, P., Khashan, A. S., Kenny, L. C., & O’Neill, S. M. (2017). Worldwide prevalence of tocophobia in pregnant women: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica, 96(8), 907–920. doi:10.1111/aogs.13138

- Pallant, J. F., Haines, H. M., Green, P., Toohill, J., Gamble, J., Creedy, D. K., & Fenwick, J. (2016). Assessment of the dimensionality of the Wijma delivery expectancy/experience questionnaire using factor analysis and Rasch analysis. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 16(1), 361. doi:10.1186/s12884-016-1157-8

- Rondung, E., Ternström, E., Hildingsson, I., Haines, H. M., Sundin, Ö., Ekdahl, J., … Rubertsson, C. (2018). Comparing internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy with standard care for women with fear of birth: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 5(3), e10420. doi:10.2196/10420

- Rondung, E., Thomten, J., & Sundin, O. (2016). Psychological perspectives on fear of childbirth. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 44, 80–91. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.10.007

- Rouhe, H., Salmela-Aro, K., Toivanen, R., Tokola, M., Halmesmaki, E., & Saisto, T. (2013). Obstetric outcome after intervention for severe fear of childbirth in nulliparous women - randomised trial. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 120(1), 75–84. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12011

- Schaverien, J. (1999). The revealing image: Analytical art psychotherapy in theory and practice. London, England: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Schouten, K. A., de Niet, G. J., Knipscheer, J. W., Kleber, R. J., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2015). The effectiveness of art therapy in the treatment of traumatized adults: A systematic review on art therapy and trauma. Trauma Violence Abuse, 16(2), 220–228. doi:10.1177/1524838014555032

- Sioma-Markowska, U., Żur, A., Skrzypulec-Plinta, V., Machura, M., & Czajkowska, M. (2017). Causes and frequency of tocophobia - own experiences. Ginekologia Polska, 88(5), 239–243. doi:10.5603/GP.a2017.0045

- Striebich, S., Mattern, E., & Ayerle, G. M. (2018). Support for pregnant women identified with fear of childbirth (FOC)/tokophobia - A systematic review of approaches and interventions. Midwifery, 61, 97–115. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2018.02.013

- Thies-Lagergren, L., Kvist, L. J., Sandin-Bojo, A. K., Christensson, K., & Hildingsson, I. (2013). Labour augmentation and fetal outcomes in relation to birth positions: A secondary analysis of an RCT evaluating birth seat births. Midwifery, 29(4), 344–350. doi:10.1016/j.midw.2011.12.014

- Tooher, R. L., Middleton, P. F., & Crowther, C. A. (2008). A thematic analysis of factors influencing recruitment to maternal and perinatal trials. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 8(1), 36. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-8-36

- Toohill, J., Fenwick, J., Gamble, J., Creedy, D. K., Buist, A., Turkstra, E., & Ryding, E. L. (2014). A randomized controlled trial of a psycho-education intervention by midwives in reducing childbirth fear in pregnant women. Birth, 41(4), 384–394. doi:10.1111/birt.12136

- Wahlbeck, H., Kvist, L. J., & Landgren, K. (2018). Gaining hope and self-confidence-An interview study of women’s experience of treatment by art therapy for severe fear of childbirth. Women and Birth, 31(4), 299–306. doi:10.1016/j.wombi.2017.10.008

- Wijma, K., Wijma, B., & Zar, M. (1998). Psychometric aspects of the W-DEQ; a new questionnaire for the measurement of fear of childbirth. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 19(2), 84–97. doi:10.3109/01674829809048501

- Winnicott, D. W. (1989). Holding and interpretation: Fragment of an analysis. London, England: Karnac.