Abstract

This meta-analysis assessed the effectiveness of mandala coloring, compared with free drawing, on state anxiety in adults. A systematic search for studies yielded eight studies, which constituted a total of 578 participants, with 289 in the mandala coloring group and 289 in the free drawing group. The results indicated that coloring mandala designs was not found to reduce state anxiety significantly more than free drawing. Larger effect sizes were found in the studies with lower precision, indicating some evidence of bias toward finding an effect. The findings suggest that mandala coloring and free drawing are equally effective coloring techniques to achieve anxiety reduction. More high-quality studies are warranted before any recommendations can be made with confidence.

Keywords:

All humans experience anxiety every now and then. Some people experience more than temporary worry or fear, with anxiety symptoms on a clinical or subclinical level. Anxiety disorders (separation anxiety disorder, selective mutism, specific phobia, social phobia, panic disorder, agoraphobia, and generalized anxiety disorder [American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013]) are the most common group of psychiatric disorders (Kessler et al., Citation1994). Furthermore, the number of people with subclinical levels of anxiety has increased in many countries over the last half-century (Twenge, Citation2000; Australian Psychological Society, Citation2015). Cattell (Citation1966) introduced the concepts of state and trait anxiety, which were further elaborated by Spielberger, who defined an emotional state as something that “exists at a given moment in time and at a particular level of intensity” (Spielberger, Citation1983, p. 6). In contrast, a personality trait is considered a more stable and enduring individual characteristic, for example, the tendency to feel anxiety (Spielberger, Citation1983). The Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is the most commonly used questionnaire of “state and trait non-disorder-specific anxiety” (Zsido et al., Citation2020). The STAI can help distinguish between clinical, subclinical, and normal levels of anxiety (Chambers et al., Citation2004; Curtis & Klemanski, Citation2015). The questionnaire is also sensitive to treatment effects (Herring et al., Citation2010).

Cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) and pharmaceuticals are the recommended treatments for clinical anxiety (National Institute of Mental Health, Citation2016). Complementary and alternative methods to treat anxiety, including dietary supplements and yoga, have been found to be more commonly used by people with self-defined anxiety, compared with conventional methods (Kessler et al., Citation2001). Art making is another possible modality. Therefore, this article reports on a meta-analysis of state anxiety in adults that compares the effects of two different modes of coloring, namely mandala coloring, and free drawing.

Literature Review

In art therapy, visual arts (such as drawing, painting, and sculpting) are integrated with psychotherapy as a means to facilitate the expression of feelings and the development of coping skills (Abbing et al., Citation2018). For instance, a one-hour art therapy session has been found to significantly reduce anxiety in hospitalized cancer patients (Nainis et al., Citation2006). Another study on college students found a significant effect on the students’ state anxiety after 30 min of art-making (Sandmire et al., Citation2012). Art therapy is both a stand-alone treatment and an integrated part of treatment programs for people with anxiety disorders.

Aside from art therapy, there are wide applications of the arts in therapeutic contexts—in particular, the use of mandala drawing and coloring. Mandala is a Sanskrit word that means “circle.” In Tibetan Buddhism, the purpose of the circle is to promote meditation, concentration, and integration by narrowing or restricting the visual field to the center (Jung, Citation1973). Jung was the first to use the mandala as a therapeutic tool (Duong et al., Citation2018). The word mandala is now typically associated with circular, geometric designs (see ), and often occurs in adult coloring books that promote mindfulness and stress relief (Henderson et al., Citation2007). However, the Jungian methodology and theory on mandalas are based on the activity of creating mandalas, not merely coloring pre-drawn templates (Mantzios & Giannou, Citation2018). Furthermore, the use of a coloring book ignores the fundamental professional relationship between the client and the therapist in art therapy (Carolan & Betts, Citation2015).

Figure 1 An Example of a Modern Pre-Drawn Mandala (Note. Obtained from http://www.free-mandalas.net)

The repeating patterns and symmetrical forms of a pre-drawn mandala supposedly enhance meditation or mindfulness while coloring (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005). Mindfulness has been found to be positively associated with psychological well-being and negatively associated with anxiety and depression (Brown & Ryan, Citation2003). Some studies on mandala coloring assume that mindfulness is the mechanism behind the effect of mandala coloring on anxiety reduction (e.g., Curry & Kasser, Citation2005), but there is limited empirical evidence of the effect of mandala coloring on mindfulness (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020). As stated by Mantzios and Giannou (Citation2018), “Without wanting to take away the Sanskrit origin and Tibetan thought and practice surrounding the use of coloring mandalas, the very basic elements of mindfulness appear to be absent from contemporary coloring books and research practices,” (p. 2) distinguishing between mindfulness and mindlessness (i.e., distracting participants from their thoughts and feelings).

In a contrast to mindfulness, flow is a state of mind of a person who is completely focused on the task at hand or who is “in the zone” (Csikszentmihalyi, Citation2020, p. 29). People tend to be in a state of flow in situations where they face a clear set of compatible goals that require appropriate responses from them. Csikszentmihalyi (Citation2020), who has studied the state of flow in art-making, describes the creative process as more important to the creators than their finished works, perhaps due to their tactile and visual experiences during art-making. It has been suggested that mandala coloring can lead to a micro flow since it does not demand a balance between challenge and skill as flow requires (Turturro & Drake, Citation2022). Research has shown that certain aspects of flow (i.e., absorption) and mindfulness are negatively correlated, whereas other aspects (e.g., a sense of personal control over the activity) are positively associated with mindfulness (Sheldon et al., Citation2015; Liu et al., Citation2020). Flow includes losing self-awareness, whereas mindfulness is about maintaining it throughout the activity at hand (Sheldon et al., Citation2015). The mechanism behind the effect of coloring mandalas on anxiety (i.e., if there is such an effect) might therefore be that of avoidance (e.g., avoiding certain thoughts), which limits interaction with reality. Avoidance has a negative connotation in North America, Europe, and Australia. In these regions avoidance strategies have been found to be among the most critical maintaining factors in models of anxiety disorders (Borkovec et al., Citation2004), whereas several Asian cultures have been said to highlight the usefulness of avoidance (Liu et al., Citation2020).

Distributors of adult coloring books reason that the books can reduce consumers’ daily anxiety at home (Ashlock et al., Citation2018). The books are relatively affordable and intuitive. Mandala coloring could constitute a tool in the toolbox for anxious people if it works, and by that, ease the work of art therapists and mental health practitioners. However, the empirical evidence on adult coloring in general, and mandala coloring in particular, is sparse and ambiguous. For this reason, the current review appraises randomized controlled trials to compare the effectiveness of mandala coloring and free drawing on state anxiety in adults.

Method

Research Design

The study employed a meta-analysis of randomized and cluster randomized controlled trials comparing the effects of mandala coloring and free drawing on state anxiety in adults. The somewhat diverging findings in the high-quality studies conducted on the effectiveness of mandala coloring on state anxiety make it important to synthesize the results, to obtain an estimate as close as possible to the unknown common truth.

Data

The data were collected from December 2020 to February 2021. The following electronic databases were searched: PubMed, PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association, was searched for additional relevant articles. We also searched for ongoing trials on the websites of the International Standard Randomized Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry and the International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (ICTRP) operated by the World Health Organization (WHO). The reference lists of identified studies were inspected. The keywords used in the search were “mandala” combined with “coloring” or “colouring” and “anxiety.” Studies were included if they (1) were published in peer-reviewed journals, (2) involved both a mandala coloring intervention group and a free drawing control group, (3) used randomized or cluster randomized controlled trials, (4) included a measure of state anxiety, and (5) included adults (aged 18+). When the studies did not report sufficient data to compute effect sizes, the authors were contacted. The first author screened the articles’ titles and abstracts for their relevance and study design according to the eligibility criteria.

Procedures

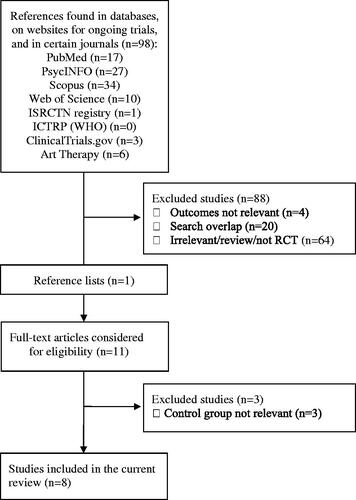

The first screening narrowed the search to eleven relevant articles. The eleven full-text articles were read and considered for eligibility by both authors but only eight studies were included in the current review (). All studies included a mandala coloring condition, where a pre-drawn mandala template and color pencils were provided, and a free drawing condition, where blank papers and color pencils were provided. Furthermore, all studies included in the current review use the STAI (Spielberger, Citation1983) as their primary outcome measure. The questionnaire consists of a state scale with 20 statements on how a person feels “right now, at this moment,” as well as a trait scale with 20 statements on how a person generally feels. All of the included studies use a version of the state scale as their outcome measure. Two studies (Mantzios & Giannou, Citation2018; Cross & Brown, Citation2019) use a short form (six items) of the state scale, developed by Marteau and Bekker (Citation1992). Another study (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005) uses an adapted version with 14 items, as opposed to the 20 items in the original scale (Spielberger et al., Citation1977). The other five studies use the original scale. All studies were single-session interventions (10–20 min).

A standard extraction sheet (Cochrane’s data extraction form for randomized controlled trial (RCT) studies) was used to summarize the ratings. The following information was extracted from each study: (1) characteristics of the sample (sample size, age range), (2) characteristics of the intervention and the control groups (distribution of the participants), (3) information about the intervention (duration), and (4) characteristics of the outcome measure (version of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory [STAI], assessment points, anxiety inducement, main findings).

Credibility

The risk of bias assessment was based on Cochrane’s risk of bias (ROB) 2 tool (Sterne et al., Citation2019). The assessments were made independently by both authors before the ratings were compared. The tool was used to individually summarize each study’s ratings. The six parameters were (1) randomization process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of the outcome, (5) selection of the reported results, and (6) overall bias. Each parameter was ranked at low risk of bias, raising some concerns, or at high risk of bias (Sterne et al., Citation2019).

Data Analysis

Means and standard deviations of change scores were used to calculate standardized mean differences (SMDs). When means and standard deviations of change scores (n = 3) were unavailable, other statistics were used to calculate effect sizes. For one study (Ashlock et al., Citation2018), we calculated the standard deviations from the confidence intervals (CIs). The authors of two other studies (Carsley & Heath, Citation2020; Koo et al., Citation2020) provided us with the mean differences and standard deviations upon request. The Hedges’ g effect sizes (Hedges & Olkin, Citation1985), with associated p-values and 95% CIs, were computed. Hedges’ g is regarded as a less biased estimate for small samples. The included studies did not have identical designs and similar samples. Therefore, a random-effects model was used to calculate mean effect sizes. All analyses were performed in Stata/MP 16.1.

Results

The searches in databases, on websites for ongoing trials, and in certain journals yielded 98 publications but only 8 met the inclusion criteria (). These 8 studies constituted a total of 578 participants, with 289 in the mandala coloring group and 289 in the free drawing group. Seven out of eight experiments were conducted on students from the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, and Australia, whereas one study comprised elderly participants in Taiwan, that is, no clinical samples. See for more study characteristics.

Table 1. Studies Included in the Review

The risk of bias assessments of the included studies was done by both authors independently. The authors reviewed and graded all eight studies according to Cochrane’s ROB 2 tool (Sterne et al., 2019) and then compared their ratings. Of the 48 ratings (6 criteria applied to 8 studies), 46 ratings were identical. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. The risk of bias assessment is presented in . The studies’ most common limitations were related to known group allocations during the interventions. In most of the studies, participants were given instructions about the intervention after randomization. Considering the slightly different instructions provided to the intervention and the control groups, those who delivered the interventions probably knew the groups to which the participants were assigned. Perhaps less concerning, the participants were not blind to the activities in which they were participating. Hopefully, they did not know the details about the other intervention(s) or the intentions of the study they participated in, but nevertheless, this might have affected the results in some ways.

Table 2. Risk of Bias Assessment of the Included Studies in the Current Review

In Mantzios and Giannou (Citation2018) study, four participants in the mandala group were excluded after randomization. The presented results omitted the excluded data, but it is unlikely that these four participants would have affected the null result found in the study. Two studies used cluster randomization (Duong et al., Citation2018; Cross & Brown, Citation2019); albeit seemingly well-conducted, these studies were deemed to be at high risk of overall bias due to their design.

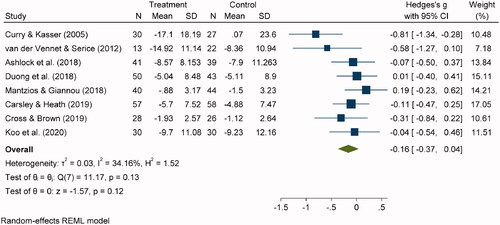

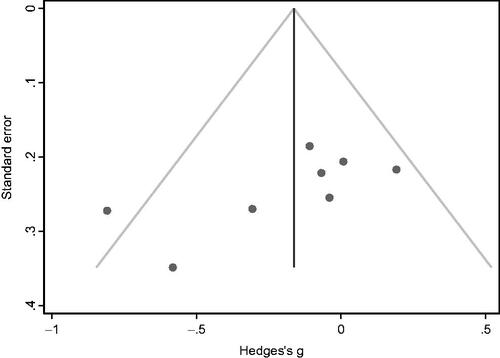

Coloring mandala designs was not found to reduce anxiety significantly more than free drawing did (Hedges’ g = −0.16, 95% CI [−0.37, 0.04], p = 0.12; 8 studies, 578 participants); see . Heterogeneity was low/moderate (I2 = 34.16%), and we applied a random-effects model using the restricted maximum likelihood (REML) estimation. The only study with a clear negative effect estimate was the seminal paper (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005). The newer and larger studies had effect estimates closer to zero. A regression-based Egger test for small-study effects indicates the presence of bias (β = −4.43, z = −2.18, p = 0.03), and as shown in , it is evident that studies with less precision have larger effect sizes. The gray lines indicate the triangular region within which 95% of the studies are expected to lie in the absence of biases and heterogeneity. Since the larger effect sizes are found in the studies with lower precision (i.e., larger standard error), there is some evidence of bias toward finding an effect.

Figure 3 Forest Plot of the Effect of Coloring Mandala Designs to Reduce Anxiety, as Compared to Free-Drawing

Figure 4 Funnel Plot of Study-Specific Effect Sizes Against Standard Error (Note. The light gray lines indicate the triangular 95% pseudo confidence interval, each dot is a single study, and the vertical line indicate the point estimate of the treatment effect)

In the subgroup analyses, we first excluded the two cluster-randomized studies that were deemed to have a high risk of overall bias (Duong et al., Citation2018; Cross & Brown, Citation2019). Similar to the results for the full sample, the effect estimate was not statistically significant (Hedges’ g = −0.19, 95% CI [−0.47, 0.09], p = 0.18; 6 studies, 431 participants). Second, since four of the eight studies included a baseline anxiety inducement before the experiments were performed (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005; van der Vennet & Serice, Citation2012; Ashlock et al., Citation2018; Koo et al., Citation2020), we conducted a separate analysis for these four studies. Again, the effect estimate was not statistically significant (Hedges’ g = −0.34, 95% CI [−0.73, 0.04], p = 0.08; 4 studies, 232 participants). Third, we repeated the analysis eight times, leaving out one study each time, and the effect estimate was only statistically significant when Mantzios and Giannou (Citation2018) study was left out (Hedges’ g = −0.22, 95% CI [−0.42, −0.01], p = 0.04; 7 studies, 494 participants).

Discussion

The findings of this meta-review reveal that mandala coloring does not reduce state anxiety significantly more than free drawing does. Heterogeneity is found to be low to moderate. The seminal paper (Curry & Kasser, Citation2005) is the only study with a clear negative effect estimate. Newer and larger studies have effect estimates closer to zero. Since the larger effect sizes are found in the studies with lower precision, there is some evidence of bias toward finding an effect. The main strength of this meta-analysis is that it bridges the results of the independent studies, of which some do and others do not find a more positive effect of mandala coloring on anxiety reduction compared with free drawing, making the current knowledge more comprehensible.

All the studies included in the current review have small convenience samples, which affect the external validity of the general public. The study samples comprise considerably more female than male participants. They also consist of more young people with higher education. Seven out of eight studies are conducted in North America, Europe, and Australia. These characteristics may also bias the results and reduce external validity. None of the studies involves a clinical sample, so the results cannot be generalized to people with anxiety disorders.

Another limitation of the studies concerns the brief interventions of mandala coloring, just 10–20 min. Instructions and ongoing guidance during the practice of mindfulness are found to be essential for people with little or no prior experience of the exercises (Mantzios & Giannou, Citation2018). A study on beginner and advanced yoga practitioners finds that advanced participants score significantly higher in mindfulness outcomes and significantly lower in stress outcomes compared with beginners (Brisbon & Lowery, Citation2009). The same principle might apply to mandala coloring.

All the included studies use self-reports on anxiety only. Such reports can be biased but have also been found to yield results that are similar to those of observational reports (Robinson et al., Citation1990) and not overly positive (Lambert et al., Citation1986). For five of the included studies, STAI is the only outcome measure. Using more than one outcome instrument is known to lessen the social desirability bias that potentially affects self-report measures of anxiety (Podsakoff et al., Citation2003).

Post-intervention anxiety is measured immediately after coloring in all the included studies in the current review. An important question that remains unanswered is how long the benefits of coloring or drawing might last. Future studies might also investigate whether there is an optimal or a minimum duration of coloring associated with anxiety reduction (Koo et al., Citation2020). Future studies should also include larger samples and non-coloring control groups, and consider the risk of bias to a greater extent, especially concerning the blinding of those who provide the intervention, as well as the information given before versus after the assignment to intervention groups, as detection bias has been found to affect research results to a great extent (Hróbjartsson et al., Citation2013).

Practical Implications

Our findings indicate that both mandala coloring and free drawing are anxiety relieving. Likewise, Ashlock et al. (Citation2018) found that all activities in their study (mandala coloring, adult coloring book, free drawing, mandala creation) are equally effective in reducing anxiety. The authors argue that although none of the activities is more anxiety-reducing than the others, adult coloring materials could be provided in typically stressful and anxiety-inducing settings, such as airports and hospital waiting rooms. It is also suggested that adult coloring can be a gateway to more advanced art therapy techniques (Kaimal et al., Citation2017). Mandala or other adult coloring patterns can also be convenient options for those who find it difficult to come up with what to draw in a free drawing activity (Ashlock et al., Citation2018). Similarly, Carsley et al. (2015) suggest that factors such as personality, fine motor skills, and experience are responsible for some people’s better response to coloring activities compared with others. Furthermore, it has been proposed that both mandala coloring and mandala creation could be used in mindfulness-based art therapy interventions, but the therapist must ensure that individual clients’ needs and therapeutic goals are met (Campenni & Hartman, Citation2020).

Limitations

Few articles were included in the study, hence the statistical power may be limited. This may be especially problematic in our subgroup and sensitivity analyses. Since different scales were used for the outcome measure in the included studies, we have chosen to use standardized mean differences (SMDs) to calculate the effect sizes, which is the standard procedure when conducting meta-analyses. However, several of the underlying assumptions for the correctness of the SMDs (e.g., that the standard deviations between studies only differ due to the different scales) have also been criticized (Cummings, Citation2011).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the findings of our meta-analysis suggest that mandala coloring does not reduce state anxiety significantly more than free drawing does. Our findings indicate that both coloring activities are anxiety relieving. There is some heterogeneity in the results of the included studies; thus, more high-quality randomized controlled trials are warranted before any confident recommendations can be made.

Data Availability Statement

The data analyzed in this study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Siri Jakobsson Støre

Siri Jakobsson Støre, PsyD, is a clinical psychologist and PhD student in the Department of Social and Psychological Studies, Karlstad University, Sweden.

Niklas Jakobsson

Niklas Jakobsson, PhD, is a full professor in economics at Karlstad Business School, Karlstad University.

References

- Abbing, A., Ponstein, A., van Hooren, S., de Sonneville, L., Swaab, H., & Baars, E. (2018). The effectiveness of art therapy for anxiety in adults: A systematic review of randomised and non-randomised controlled trials. PLoS One, 13(12), e0208716. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0208716

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Ashlock, L. E., Miller-Perrin, C., & Krumrei-Mancuso, E. (2018). The effectiveness of structured coloring activities for anxiety reduction. Art Therapy, 35(4), 195–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2018.1540823

- Australian Psychological Society. (2015). Stress and wellbeing. Australian Psychological Society.

- Borkovec, T. D., Alcaine, O. M., & Behar, E. (2004). Avoidance theory of worry and generalized anxiety disorder. In R. G. Heimberg, C. L. Turk, & D. S. Mennin (Eds.), Generalized anxiety disorder: Advances in research and practice (pp. 77–108). The Guilford Press.

- Brisbon, N. M., & Lowery, G. A. (2009). Mindfulness and levels of stress: A comparison of beginner and advanced hatha yoga practitioners. Journal of Religion and Health, 50, 931–941. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-009-9305-3

- Brown, W. K., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

- Campenni, C. E., & Hartman, A. (2020). The effects of completing mandalas on mood, anxiety, and state mindfulness. Art Therapy, 37(1), 25–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1669980

- Carolan, R., & Betts, D. (2015). The adult coloring book phenomenon: The American Art Therapy Association weighs in. 3BL MEDIA. http://3blmedia.com/News/Adult-Coloring-Book-Phenomenon

- Carsley, D., & Heath, N. L. (2020). Effectiveness of mindfulness-based coloring for university students’ test anxiety. Journal of American College Health, 68(5), 518–527. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2019.1583239

- Cattell, R. B. (1966). Patterns of change: Measurement in relation to state dimension, trait change, lability, and process concepts. In Handbook of multivariate experimental psychology. Rand McNally & Co.

- Chambers, J. A., Power, K. G., & Durham, R. C. (2004). The relationship between trait vulnerability and anxiety and depressive diagnoses at long-term follow-up of generalized anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 18(5), 587–607. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2003.09.001

- Cross, G., & Brown, P. M. (2019). A comparison of the positive effects of structured and nonstructured art activites. Art Therapy, 36(1), 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1564642

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (2020). Finding flow: The psychology of engagement with everyday life. Hachette.

- Cummings, P. (2011). Arguments for and against standardized mean differences (effect sizes). Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(7), 592–596. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.97

- Curry, N. A., & Kasser, T. (2005). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? Art Therapy, 22(2), 81–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2005.10129441

- Curtis, J., & Klemanski, D. H. (2015). Identifying individuals with generalised anxiety disorder: A receiver operator characteristic analysis of theoretically relevant measures. Behaviour Change, 32(4), 255–272. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2015.15

- Duong, K., Stargell, N. A., & Mauk, G. W. (2018). Effectiveness of coloring mandala designs to reduce anxiety in graduate counseling students. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 13(3), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2018.1437001

- Hedges, L., & Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical method for meta-analysis. Academic Press.

- Henderson, P., Rosen, D., & Mascaro, N. (2007). Empirical study on the healing nature of mandalas. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 1(3), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1037/1931-3896.1.3.148

- Herring, M. P., O’Connor, P. J., & Dishman, R. K. (2010). The effect of exercise training on anxiety symptoms among patients: A systematic review. Archives of Internal Medicine, 170(4), 321–331. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2009.530

- Hróbjartsson, A., Thomsen, A. S. S., Emanuelsson, F., Tendal, B., Hilden, J., Boutron, I., Ravaud, P., & Brorson, S. (2013). Observer bias in randomized clinical trials with measurement scale outcomes: A systematic review of trials with both blinded and nonblinded assessors. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 185(4), E201–E211. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.120744

- Jung, C. G. (1973). Mandala symbolism (3rd printing). Princeton University Press.

- Kaimal, G., Mensinger, J. L., Drass, J. M., & Dieterich-Hartwell, R. M. (2017). Art therapist-facilitated open studio versus coloring: Differences in outcomes of affect, stress, creative agency, and self-efficacy. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 30(2), 56–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2017.1375827

- Kessler, R. C., McGonagle, K. A., Zhao, S., Nelson, C. B., Hughes, M., Eshleman, S., Wittchen, H. U., & Kendler, K. S. (1994). Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM-III-R psychiatric disorders in the United States. Results from the National Comorbidity Survey. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002

- Kessler, R. C., Soukup, J., Davis, R. B., Foster, D. F., Wilkey, S. A., Van Rompay, M. I., & Eisenberg, D. M. (2001). The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(2), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.289

- Koo, M., Chen, H.-P., & Yeh, Y.-C. (2020). Coloring activities for anxiety reduction and mood improvement in Taiwanese community-dwelling older adults: A randomized controlled study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2020(6), 6964737. https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/6964737

- Lambert, M. J., Hatch, D. R., Kingston, M. D., & Edwards, B. C. (1986). Zung, Beck, and Hamilton Rating Scales as measures of treatment outcome: A meta-analytic comparison. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(1), 54–99. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.54.1.54

- Liu, C., Chen, H., Liu, C.-Y., Lin, R.-T., & Chiou, W.-K. (2020). Cooperative and individual mandala drawing have different effects on mindfulness, spirituality, and subjective well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 564430. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.564430

- Mantzios, M., & Giannou, K. (2018). When did coloring books become mindful? Exploring the effectiveness of a novel method of mindfulness-guided instructions for coloring books to increase mindfulness and decrease anxiety. Frontiers in Psychology, 9(56), 56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00056

- Marteau, T. M., & Bekker, H. (1992). The development of a six-item short-form of the state scale of the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 31(3), 301–306. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1992.tb00997.x

- Nainis, N., Paice, J. A., Ratner, J., Wirth, J. H., Lai, J., & Shott, S. (2006). Relieving symptoms in cancer: Innovative use of art therapy. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 31(2), 162–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2005.01.232

- National Institute of Mental Health. (2016). Anxiety disorders. http://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/topics/anxiety-disorders/index.shtml#part_145338

- Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903. https://doi.org/10.1037/00219010.88.5.879

- Robinson, L. A., Berman, J. S., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1990). Psychotherapy for the treatment of depression: A comprehensive review of controlled outcome research. Psychological Bulletin, 108(1), 30–49. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.108.1.30

- Sandmire, D. A., Gorham, S. R., Rankin, N. E., & Grimm, D. R. (2012). The influence of art making on anxiety: A pilot study. Art Therapy, 29(2), 68–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.683748

- Sheldon, K. M., Prentice, M., & Halusic, M. (2015). The experiential incompatibility of mindfulness and flow absorption. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 22, 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550614555028

- Spielberger, C. D. (1983). Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory STAI. Mind Garden.

- Spielberger, C. D., Gorusch, R. L., Jacobs, G. A., Lushene, R., & Vagg, P. R. (1977). State-Trait Anxiety Inventory for Adults (Form Y). Mind Garden. http://www.mindgarden.com/145-state-trait-anxiety-inventory-for-adults

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H.-Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ, 366, l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Turturro, N., & Drake, J. E. (2022). Does coloring reduce anxiety? Comparing the psychological and psychophysiological benefits of coloring versus drawing. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 40(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276237420923290

- Twenge, J. M. (2000). The age of anxiety? The birth cohort change in anxiety and neuroticism, 1952-1993. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79(6), 1007–1021. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.6.1007

- van der Vennet, R., & Serice, S. (2012). Can coloring mandalas reduce anxiety? A replication study. Art Therapy, 29(2), 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2012.680047

- Zsido, A. N., Teleki, S. A., Csokasi, K., Rozsa, S., & Bandi, S. A. (2020). Development of the short version of the Spielberger state-trait anxiety inventory. Psychiatry Research, 291, 113223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113223