Abstract

The purpose of this study was to evaluate if a single session mindfulness-based art therapy doodle intervention may support and improve: (a) mindfulness, (b) mindful creativity, and (c) positive and negative emotional states. A general community sample of 71 adult participants engaged in the mindful doodling virtual two-hour workshops. Based on retrospective methods from participant self-reported perceptions before and after the workshop, there were statistically significant increases in ratings of mindfulness, mindful creativity, and positive emotions, as well as decreases in negative emotions (p < .05). The results suggested the potential efficacy and clinical benefit of this single session art therapy intervention for promoting mindfulness, creativity, and positivity in the community.

The development of mindfulness-based art therapy was influenced by the proven centrality of mindfulness research and psychotherapy (Ferrari et al., Citation2019; Khoury et al., Citation2015; Pascoe et al., Citation2017). Mindful doodling has been shown to support the expression and awareness of implicit emotions, thoughts, and perceptions (Isis, Citation2016; Qutub, Citation2012). This study examined the impact of a single session mindfulness-based art therapy doodle intervention on mindfulness, mindful creativity, and emotional states.

Theoretical and Clinical Foundations

The primary focus of mindfulness is to develop present moment awareness, a non-judgmental stance, acceptance, and loving kindness (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2013). Mindfulness art therapy approaches include mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT), which was pioneered by Caroline Peterson (Beerse et al., Citation2020; Monti et al., Citation2006), and mindfulness self-compassion art therapy (MSCAT) programs (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2023; Ho et al., Citation2019; Isis, Citation2014; Joseph & Bance, Citation2019). MBAT was designed based on Mindfulness-based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Kabat-Zinn, Citation2013). The three MBSR and MBAT theoretical foundations are: here-and-now awareness of bodily sensations, awareness of feelings, and awareness of attitudes or mind states (Goldstein, Citation2013). MBAT integrates mindfulness practices with drawing, painting, sculpting, and poetry (Bokoch & Hass-Cohen, Citation2020; Coholic et al., Citation2020). It is likely that the inclusion of art therapy supports the exploration and expression of implicit emotions via non-verbal means (Hass-Cohen & Clyde-Findlay, Citation2015), further contributing to an overall decrease in nervous system arousal propensities (Jang et al., Citation2018). MBSR and MBAT research has demonstrated efficacy mostly for six to eight week curriculums. Both MBSR and MBAT have demonstrated efficacy for community samples, and multiple clinical and medical conditions (Beerse et al., Citation2020; Khoury et al., Citation2015; Monti et al., Citation2006; Pascoe et al., Citation2017; Peterson, Citation2015; Querstret et al., Citation2020; Wielgosz et al., Citation2019; Zeidan, Johnson, Gordon, et al., Citation2010).

Associated with positive psychology, MSCAT approaches include focusing-oriented art therapy (FOAT) (Isis, Citation2014; Rappaport, Citation2009), compassion-oriented art therapy (COAT) (Beaumont, Citation2012), and mindfulness self-compassion art therapy (MSCAT; Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2023; Ho et al., Citation2019; Joseph & Bance, Citation2019). Positive psychology interventions have demonstrated efficacy for non-clinical and clinical populations (Chakhssi et al., Citation2018). MSCAT is associated with positive psychology, as every intervention starts with bringing self-compassion and compassion to all experiences (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2023; Williams, Citation2018). FOAT combines the principles of focusing and art therapy to increase safety, as well as facilitate art-based interventions. Focusing, supports clients’ acceptance of the affective and cognitive responses to their art (Rappaport, Citation2009). FOAT also allows for distancing between the client and their experience of trauma and therapeutic containment (Rappaport, Citation2009). COAT combines the principles of Gilbert’s compassion-focused psychotherapy (Citation2020) and art therapy to mitigate shame and develop acceptance. COAT focuses on empowering clients to engage in self-soothing in order to reduce threat-based emotions (Beaumont, Citation2012). MSCAT programs integrate mindfulness and self-compassion and the arts psychotherapy (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2023; Ho et al., Citation2019; Isis, Citation2016; Joseph & Bance, Citation2019). Positive psychology art therapy uses the arts for mobilizing client strengths though experiences of flow and the expression of positive emotions, such as in doodling (Wilkinson & Chilton, Citation2017). From a positive psychology perspective, reflections on positive marks and imagery from the completed doodle promotes a sense of well-being (Isis, Citation2015). MBAT and positive psychology art therapy approaches have informed the construction of the current study’s mindfulness-based art therapy doodle intervention.

Scribbling and Doodling

Historically, the terms scribbling and doodling may be used interchangeably and described with similar characteristics and clinical benefits (Brown, Citation2014). Since the inception of art therapy, Hanna Kwiatkowska, used scribbling as a warm-up technique to help people access implicit emotions and openness to experiences (Kalmanowitz & Ho, Citation2016). Scribbling also helps people to approach art and meaning-making, especially when they may find it difficult to engage with verbal or visual expression (Malchiodi, Citation2003). Scribbling and doodling are considered to be expressive kinesthetic activities (Malchiodi, Citation2003). From a psychodynamic perspective, scribbling facilitates free association and assists in projecting complex experiences (Rubin, Citation2016). This art-based projection allows for the expression of internal mental states and reduces the stigma associated with formal drawing prompts (Nash, Citation2020). According to Jung (Citation1981) drawing within a circle, also called a mandala, promotes therapeutic safety due to the emergence of maternal archetypes and protective imagery (Kellogg, Citation1978). Working within a circle increases awareness and is considered a mindfulness technique (Isis, Citation2016).

Clinically, scribbling and doodling have been found to improve a wide variety of clinical concerns, such as: anxiety, communication, self-image, attention, and has been used with diverse populations of children and adults. For children, sensory-based scribbling has been shown to improve communication, self-image, and flexibility on the autism spectrum (Schweizer et al., Citation2014). For adults, short-term interventions that have integrated scribbling and mindfulness techniques have been found to increase refugees’ coping (Kalmanowitz & Ho, Citation2016). Similarly, a mindfulness and body-based program that included scribbling for women experiencing homelessness found a significant decrease in distress (Dabney, Citation2020).

Neurobiological-based advantages for scribbling may help reduce distress, by accessing right hemisphere non-verbal feelings (Chapman, Citation2014). Drawing a scribble within a circle has been associated with the treatment of anxiety (Hass-Cohen & Clyde-Findlay, Citation2015), and containment of traumatic experiences (Campbell et al., Citation2016). Scribbling may maintain brain arousal at an ideal level and reduce default mode network rumination (Schott, Citation2011). Doodling is also theorized to contribute to right and left hemispheric integration (McNamee, Citation2004). Distractions, such as daydreaming, are triggered by activation of the default mode network, and may constrain executive function (Hass-Cohen & Clyde-Findlay, Citation2015). However, scribbling, which requires paying attention to external stimuli, does not constrain executive functioning; thus, making it a helpful mindfulness intervention (Hass-Cohen & Clyde-Findlay, Citation2015). Doodling within a circle has been shown to increase self-perceptions of creativity, while activating reward pathways that aid in emotion regulation (Kaimal et al., Citation2017).

Single Session Mindfulness-based Art Therapy Doodle Intervention

Single sessions were pioneered by Talmon (Citation1990), who worked in a medical setting. Single mindfulness sessions, or brief meditation interventions, allow for the implementation of mindfulness concepts without the time commitment and extensive homework assignments needed to participate in 8-week MBSR or MBAT courses (Jankowski & Holas, Citation2020; Sumantry & Stewart, Citation2021, Ueberholz & Fiocco, Citation2022). Results from neuroimaging supported the benefits of 15-minute meditation practices (Johnson et al., Citation2015). A brief meditation intervention, which did not require homework, was found to improve negative mood symptoms, tension, and fatigue (Zeidan, Johnson, Diamond, et al., Citation2010). College students who engaged in a 15-minute meditation reported significant reduction in intensity of affect, regardless of their previous experience with meditation (Thompson & Waltz, Citation2007). Brief meditation interventions with college students were found to reduce fatigue and anxiety, while increasing mindfulness and mood (Zeidan, Johnson, Diamond, et al., Citation2010). Efficacy has been demonstrated for a one-time art therapy intervention for trauma and pain (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2018). This research suggested the utility for examining the efficacy for single session mindfulness-based art therapy interventions in the community.

The purpose of the current study was to examine the efficacy of a single session positive psychology and MBAT doodling intervention workshop with a community sample. For purposes of the current study, doodling is the preferred term rather than scribbling, as it has been more often associated with mindfulness (Brown, Citation2014). From a mindfulness perspective, this article has defined doodling as intention-driven, non-judgmental, present-moment awareness scribbling (Isis, Citation2016). The intervention included a doodling warm up, containment within a circle, and manipulation of the image in order to enhance mindfulness, creativity, and positive emotional states.

Methods

Research Design

This study used a retrospective pretest-posttest single group design (RPP) (Howard et al., Citation1979). RPP collects pretest data concurrently with posttest data. For example, participants were asked to evaluate their mindfulness now (after the intervention), and then recall and evaluate their mindfulness before the intervention. Alliant International University IRB approval was obtained (Protocol#: 2003173073).

Participants

A convenience sample within the community was recruited online via Eventbrite and other social media platforms, as well as psychology and art therapy graduate school campuses. There were 71 adult participants, with ages ranging from 22 to 80 years old (M = 40.07 years, SD = 15.70). Most participants identified as White (n = 34; 47.9%), women (n = 46; 64.8%), art therapists (licensed or in-training; n = 30; 42.3%), who engage in art-making (n = 40; 56.3%) and mindfulness (n = 44; 62.0%) practices ().

Table 1. Participant Demographics

Measures

Demographic Questionnaire

The demographic questionnaire asked participants to report on their personal characteristics including ethnicity, age, gender identity, profession, and experience with mindfulness and the arts.

Toronto Mindfulness Scale

This 13-item, 5-point Likert scale measure assesses trait mindfulness in the areas of curiosity and decentering, with higher scores indicating higher levels of mindfulness. This measure was normed on a sample of 374 adult participants, who had a range of mindfulness experience, and showed strong internal consistency reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of .95 (Lau et al., Citation2006). This study sample also showed good reliability with Cronbach’s alpha values ranging from .80-.90.

Discrete Emotions Scale-Adapted

The Discrete Emotions Scale-Adapted (DES-A) is an 11-item, 5-point Likert scale questionnaire about emotions, which includes four subscales assessing the intensity of different emotions: anger, happiness, fear, and aversion (van der Schalk et al., Citation2011). The DES-A was normed on 180 psychology students and had strong reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .93). In this study, the questionnaire was modified to not include the aversion subscale as the intervention was not designed to address aversion. All subscales had adequate reliability (Cronbach’s alpha = .69–.92).

Non-Standardized Scales

Two non-standardized scales were created by the authors to capture aspects of the intervention experience that they anticipated based on clinical experience working with clients using this intervention, that were not captured by the available standardized measures. One scale aimed to capture positive and compassion-based emotions, such as: accepting, peaceful, supported, loving, kind, and secure. This scale had 6 items on a 5-point Likert scale, modeled after the DES-A, with 1 indicating slightly or not at all, and 5 meaning extremely. This positive emotion scale showed strong internal consistency reliability with the study sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .90-.91). A second scale was created to capture aspects of mindful creativity, including: imagination, attention, creativity, awareness of thoughts and feelings, connection, positivity, non-judgment, and non-reactivity. This scale had nine items and used a 7-point Likert scale indicating low to high levels of the state. The mindful creativity scale showed good reliability with this sample (Cronbach’s alpha = .85–.90).

Procedures

The intervention took place during two-hour live synchronous workshops delivered online via Zoom. Participants were provided the informed consent and demographic questionnaire to complete before the workshop. On the day of the workshops, participants were greeted and asked to have their materials ready, which included two sheets of white paper, one with a pre-drawn circle, pencils with erasers, glue, scissors, and choice of coloring tool. The presenter began with a brief mindfulness exercise asking participants to check in with their mind and non-judgmentally observe their thoughts. They were asked to doodle their thoughts on one of the pieces of paper, using pencil or pen, without judgment or blame. Next participants were asked to use color in order to embellish aspects of the original doodles that drew their attention to what felt beneficial to them right now. For the last step, the reconstructed doodle, participants were again invited to reflect on their embellished doodle. Additionally, the following instructions were provided: “If you would like, cut out what you wish to keep or work on from the doodle to which you have just added elements or color, and then arrange and glue it onto the second piece of paper with the pre-drawn circle on it. Continue to work on it until it feels helpful for you.” At each stage of the doodle creation process, participants were invited to take digital images of their work. Following the completion of the reconstructed doodle art, participants were split up into pairs in breakout rooms to engage in a mindful listening activity, where they were encouraged to listen to each other without interruption, advice-giving, or interpretations. At the completion of the art-making and before sharing with others, participants were invited to complete the RPP measures (Howard et al., Citation1979).

Validity

Participants were asked to retrospectively self-assess their perceptions and states of mind both before and after the workshop. The RPP retrospective research design (Howard et al., Citation1979) required the administration of both the pretest and posttest after the intervention. RPP provides distinct advantages to traditional pretest-posttest designs for the following reasons: a) reduction in participant burden; b) mitigating retest effects in brief interventions, especially when high-face-value measures are used (Little et al., Citation2020); c) reduced reactivity; and d) elimination of response shift bias (RSB) issues. RSB represents a threat to internal validity as participants’ internal understanding of a construct changes as a result of engaging in an intervention (Howard et al., Citation1979). RSB is when participants, rating themselves on self-report measures, use a different internal standard between ratings (Howard et al., Citation1979). For example, in mindfulness approaches, the definition of awareness includes not only being aware of internal experiences, but also being simultaneously aware that internal experiences are impermanent. Psychological definitions of awareness are synonymous with insight, and do not include insight to the coming and going of such awareness. Thus, participant’s RPP responses are more likely to represent internalized, consistent perceptions of the research constructs, as they have been exposed to the intervention of interest before giving any of their responses (Chang & Little, Citation2018). RPP is therefore most useful when assessing noncognitive variables, such as attitudes and beliefs (Little et al., Citation2020). Specific intervention prompts and a detailed outline of procedures with a consistent program facilitator were used to ensure future research replicability.

Data Analysis

Paired samples t-tests were used to assess for differences in participants’ perceptions of their experience before and after the workshops for each standardized and non-standardized measure, which included the following variables: mindfulness, mindful creativity, happiness, positive emotions, anger, and fear. Participant samples are also described in the results section to highlight the quantitative results.

Results

Descriptive statistics of all standardized outcome measures were explored and compared to psychometric norms (). The current sample fell within the expected range of responses. Most of the quantitative measures were standardized. Non-standardized measures were only used to capture further aspects of mindfulness and positive emotions that were not covered in the standardized measures.

Table 2. Descriptive Statistics of Standardized Outcome Measures

Normality assumptions were checked and met for all outcome variables, except the Discrete Emotions Scale-Anger Subscale. Transformations were attempted but were not able to correct for a normal distribution, therefore a non-parametric Wilcoxon signed rank test was used to support the parametric paired samples t-test results for this subscale. Wilcoxon signed rank tests were also used to support the parametric paired samples t-test results for the non-standardized outcome variables (i.e. positive emotions, mindful creativity).

Paired samples t-tests and Wilcoxon signed ranks tests revealed a statistically significant difference between retrospective pretest and posttest measures for all outcome variables after the workshops. Mindfulness, mindful creativity, happiness, and positive emotions significantly increased, while fear and anger significantly decreased ().

Table 3. Differences Over Time

Discussion

The purpose of this empirical study was to determine if a single session mindfulness-based art therapy doodling intervention could increase: (a) mindfulness (i.e. present moment awareness of thoughts and feelings); (b) sense of mindful creativity (i.e. imagination); and (c) positive emotional states (i.e. feelings of happiness such as peaceful, supported, loving, connected, and secure), while decreasing negative emotional states (i.e. anger and fear). Based on retrospective data collection methods of participant self-reported perceptions before and after the workshop, there were statistically significant increases in ratings of mindfulness, mindful creativity, and positive emotions, as well as significant decreases in negative emotions.

These results are in line with the review of the literature, which has demonstrated that the integration of mindfulness-based practices and art therapy support the advantages of mindfulness and positive psychology (Isis, Citation2016). Likely, specific advantages were increased mindfulness states. Creating intention-based doodle images to represent each here-and-now thought and carefully placing them on the paper, aimed to portray a tangible, current view of thoughts, feelings, and emotions. This visual process likely triggered an enhanced awareness of thoughts and feelings in the here-and-now (Schott, Citation2011). It is likely that the doodling supported access to momentary thoughts and feelings (Malchiodi, Citation2003). It is possible that when participants revisited their doodle, and selected a beneficial aspect of their doodle, there was enhanced positivity (Chapman, Citation2014).

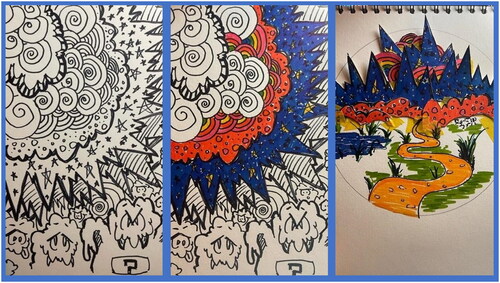

For example, a participant expressed their experience of decreased anger: “I used the face drawings from my initial doodle in my first piece and then I created a new piece. I shared both [drawings] with my partner at the end, and had a meaningful connection that I almost missed because I wanted to avoid talking or showing my face. The sharing ended up being the most helpful piece of this experience. Although it felt like every step was essential, I am fond of my new pieces as they were helpful steps in allowing myself to grieve (I had gotten upsetting news that day and had spent the morning angry and crying)” (see ).

This increased sense of mindful creativity likely not only increased positive emotional states, but also decreased negative emotional states at the same time. It is also likely that the option of revising and changing the art to be a more satisfactory product contributed to the positive results (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2014). Subsequently, visually highlighting the most beneficial thoughts and emotions, and cutting them out and placing them within a circle, may have further supported positivity (Wilkinson & Chilton, Citation2017).

It is hypothesized that the three-dimensionality created by the cutting and pasting increased vivid, positive, sensory perceptions. The first image within on the left shows the first doodle, which is a black and white scribble with expanding spirals and spikes, as well as some ghost-like figures with seemingly unhappy facial expressions. The second image shows how the initial doodle was then embellished in red and blue colors, which have been associated with conflict (Kellogg, Citation1978). The third image shows the reconstructed art, which is three-dimensional and does not include the ghost-like figures. In this final image, the expanding spirals and spikes have been transformed into a path, suggesting a journey. Paths and journeys have been associated with positive outcomes (Kellogg, Citation1978). Furthermore, the pathway depicted in naturalistic green and orange colors connects the two halves of the circle, perhaps suggesting some conflict resolution and a view to the future.

Practical Implications

The most important practical implication is the process of selecting beneficial aspects of the art-making, in this case doodling. The dynamic process of creating changes in art supports resiliency and recovery (Hass-Cohen et al., Citation2014) and can likely be tailored to accommodate a diversity of people and settings utilizing minimal art supplies and time; however, further research is needed to support this claim.

Limitations

This study was conducted with a self-selected community sample, which suggested a community interest in such interventions. Moreover, a large number of the participants had previous experience with mindfulness practices. Additionally, due to the sample size and non-normal distribution of some measures, nonparametric Wilcoxon signed rank test were used. Therefore, research with a more diverse and larger community, as well as clinical samples, is needed to further substantiate these findings. The retrospective design of this study may have influenced the results, as for some participants their initial responses may have faded. One of the disadvantages is that RPP responses may represent a memory bias to align previous attitudes with current attitudes (Campbell & Stanley, Citation1963). For example, participants may respond similarly to the pretest and posttest items due to social desirability and the need to align their sense of self as mindful, both before and after the intervention. This may more often happen with positive constructs, such as mindfulness. It is likely that when data is collected anonymously, online, and immediately following the workshop, these biases can be mitigated (Campbell & Stanley, Citation1963). It is recommended that future clinical studies use a pretest-posttest experimental control group design.

Conclusion

This study focused on a mindful doodling technique. It was shown to be significantly helpful for a non-clinical community sample. The interventionshifted participants’ attention toward present-moment awareness of thoughts and emotions. The study is an example of how to use mindful creative expression to gain access to positive thoughts and emotions and decrease negative emotions.

Disclosure

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Patricia Isis

Patricia Isis, PhD, LMHC-QS, ATR-BC, ATCS, is an art therapist in Private Practice at Miami Art Therapy and Mindfulness Trainings, Miami, FL.

Rebecca Bokoch

Rebecca Bokoch, PsyD, LMFT, is an Assistant Professor in the Clinical PhD Program, California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University, Alhambra, CA.

Grace Fowler

Grace Fowler, PhD, is an Adjunct Professor in the Couples Family Therapy Masters Online Program, California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University.

Noah Hass-Cohen

Noah Hass-Cohen, PsyD, ATR-BC, is Professor in Couples Family Therapy Masters and Doctoral Programs, California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University, Alhambra CA.

References

- Beaumont, S. (2012). Art therapy for gender-variant individuals: A compassion-oriented approach. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 25(2), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2012.11415565

- Beerse, M. E., Van Lith, T., & Stanwood, G. (2020). Therapeutic psychological and biological responses to mindfulness-based art therapy. Stress and Health, 36(4), 419–432. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2937

- Bokoch, R., & Hass-Cohen, N. (2020). Effectiveness of a school-based mindfulness and art therapy group program. Art Therapy, 38(3), 117–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2020.1807876

- Brown, S. (2014). The doodle revolution: Unlock the power and think differently. Penguin Group.

- Campbell, D. T., & Stanley, J. G. (1963). Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research. Rand McNally.

- Campbell, M., Decker, K. P., Kruk, K., & Deaver, S. P. (2016). Art therapy and cognitive processing therapy for combat-related PTSD: A randomized controlled trial. Art Therapy, 33(4), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1226643

- Chakhssi, F., Kraiss, J. T., Sommers-Spijkerman, M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2018). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1739-2

- Chang, R., & Little, T. D. (2018). Innovations for evaluation research: Multiform protocols, visual analog scaling, and the retrospective pretest–posttest design. Evaluation & The Health Professions, 41(2), 246–269. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163278718759396

- Chapman, L. (2014). Neurobiologically informed trauma therapy with children and adolescents: Understanding mechanisms of change. W. W. Norton.

- Coholic, D., Schwabe, N., & Lander, K. (2020). A scoping review of arts-based mindfulness interventions for children and youth. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 37(5), 511–526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-020-00657-5

- Dabney, A. L. (2020). Exploring pathways toward psychobiological safety through mindful body-centered art making with sheltered homeless women [Doctoral dissertation]. Notre Dame de Namur Université.

- Ferrari, M., Hunt, C., Harrysunker, A., Abbott, M. J., Beath, A. P., & Einstein, D. A. (2019). Self-compassion interventions and psychosocial outcomes: A meta-analysis of RCTs. Mindfulness, 10(8), 1455–1473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01134-6

- Gilbert, P. (2020). Compassion: From its evolution to a psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 586161. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586161

- Goldstein, J. (2013). Mindfulness: A practical guide to awakening. Sounds True.

- Hass-Cohen, N., Bokoch, R., Clyde Findlay, J., & Banford, A. (2018). A four-drawing art therapy trauma and resiliency protocol study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 61, 44–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2018.02.003

- Hass-Cohen, N., Bokoch, R., & Fowler, G. (2023). The compassionate arts psychotherapy program: Benefits of a compassionate arts media continuum. Art Therapy, 40(1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2022.2100690

- Hass-Cohen, N., & Clyde-Findlay, J. (2015). Art therapy and the neuroscience of relationships, creativity, and resiliency: Skills and practices. W.W. Norton & Company.

- Hass-Cohen, N. C., Findlay, J., Carr, R., & Vanderlan, J. (2014). “Check change what you need to change and/or keep what you want”: An art therapy neurobiological-based trauma protocol. Art Therapy, 31(2), 69–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2014.903825

- Ho, A. H. Y., Tan-Ho, G., Ngo, T. A., Ong, G., Chong, P. H., Dignadice, D., & Potash, J. (2019). A novel mindful-compassion art therapy (MCAT) for reducing burnout and promoting resilience for end-of-life care professionals: A waitlist RCT protocol. Trials, 20, 406. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-019-3533-y

- Howard, G. S., Ralph, K. M., Gulanick, N. A., Maxwell, S. E., Nance, D. W., & Gerber, S. K. (1979). Internal invalidity in pretest-posttest self-report evaluations and a re-evaluation of retrospective pretests. Applied Psychological Measurement, 3, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/014662167900300101

- Isis, P. (2014). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and the expressive therapies in a hospital-based community outreach program. In L. Rappaport (Ed.), Mindfulness and the Arts Therapies. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Isis, P. (2015). Positive art therapy. In D. Gussack & M. Rosal (Eds.), The Wiley Blackwell handbook of art therapy. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Isis, P. (2016). The mindful doodle book: 75 creative exercises to help you live in the moment. PESI Publishing and Media.

- Jang, S. H., Lee, J. H., Lee, H. J., & Lee, S. Y. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based art therapy on psychological symptoms in patients with coronary artery disease. Journal of Korean Medical Science, 33(12), e88.

- Jankowski, T., & Holas, P. (2020). Effects of brief mindfulness meditation on attention switching. Mindfulness, 11(5), 1150–1158. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-020-01314-9

- Johnson, S., Gur, R. M., David, Z., & Currier, E. (2015). One-session mindfulness meditation: A randomized controlled study of effects on cognition and mood. Mindfulness, 6(1), 88–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-013-0234-6

- Joseph, M., & Bance, L. O. (2019). A pilot study of compassion-focused visual art therapy for sexually abused children and the potential role of self-compassion in reducing trauma-related shame. Indian Journal of Health & Wellbeing, 10, 368–372.

- Jung, C. G. (1981). The archetypes and the collective unconscious (2nd ed.). Princeton University Press.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living (Revised edition): Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. Bantam.

- Kaimal, G., Ayaz, H., Herres, J., Dieterich-Hartwell, R., Makwana, B., Kaiser, D. H., & Nasser, J. A. (2017). Functional near-infraread spectrosocopy assessment of reward perception based on visual self-expression: Coloring, doodling, and free drawing. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 55, 85–92. https://doi.org/10.10106/j.aip.2017.05.004

- Kalmanowitz, D., & Ho, R. T. H. (2016). Out of our mind. Art therapy and mindfulness with refugees, political violence and trauma. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 49, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.05.012

- Kellogg, J. (1978). Mandala: Path of beauty. Kellog.

- Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

- Lau, M. A., Bishop, S. R., Segal, Z. V., Buis, T., Anderson, N. D., Carlson, L., Shapiro, S., Carmody, J., Abbey, S., & Devins, G. (2006). The Toronto Mindfulness Scale: Development and validation. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(12), 1445–1467. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20326

- Little, T. D., Chang, R., Gorrall, B. K., Waggenspack, L., Fukuda, E., Allen, P. J., & Noam, G. G. (2020). The retrospective pretest–posttest design redux: On its validity as an alternative to traditional pretest–posttest measurement. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(2), 175–183. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419877973

- Malchiodi, C. A. (2003). Handbook of art therapy. Guilford Press.

- McNamee, C. M. (2004). Using both sides of the brain: Experiences that integrate art and talk therapy through scribble drawings. Art Therapy, 21(3), 136–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2004.10129495

- Monti, D. A., Peterson, C., Kunkel, E. J., Hauck, W. W., Pequignot, E., Rhodes, L., & Brainard, G. C. (2006). A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for women with cancer. Psycho-oncology, 15(5), 363–373. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.988

- Nash, C. (2020). Doodling as a measure of burnout in healthcare researchers. Culture, Medicine, and Psychiatry, 2020, 1–34. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11013-020-09690-6

- Pascoe, M. C., Thompson, D. R., Jenkins, Z. M., & Ski, C. F. (2017). Mindfulness mediates the physiological markers of stress: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychiatric Research, 95, 156–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2017.08.004

- Peterson, C. (2015). Walkabout: Looking in, looking out: A mindfulness-based art therapy program. Art Therapy, 32(2), 78–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2015.1028008

- Querstret, D., Morison, L., Dickinson, S., Cropley, M., & John, M. (2020). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for psychological health and well-being in nonclinical samples: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 27(4), 394. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000165

- Qutub, A. (2012). Communicating symbolically: The significant of doodling between symbolic interaction and psychoanalytical perspectives. Colloquy, 8, 72–85.

- Rappaport, L. (2009). Focusing-oriented art therapy: Accessing the body’s wisdom and creative intelligence. Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Rubin, J. (2016). Approaches to art therapy: Theory and technique (3rd ed.). Routledge.

- Schott, G. D. (2011). Doodling and the default network of the brain. The Lancet, 378(9797), 1133–1134. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61496-7

- Schweizer, C., Knorth, E. J., & Spreen, M. (2014). Art therapy with children with autism spectrum disorders: A review of clinical case descriptions on ‘what works’. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 577–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.10.009

- Sumantry, D., & Stewart, K. E. (2021). Meditation mindfulness and attention: A meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 12(6), 1332–1349. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-021-01593-w

- Talmon, M. (1990). Single-session therapy: Maximizing the effect of the first (and often only) therapeutic encounter. Jossey-Bass.

- Thompson, B. L., & Waltz, J. (2007). Everyday mindfulness and mindfulness meditation: Overlapping constructs or not? Personality and Individual Differences, 43(7), 1875–1885. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.06.017

- Ueberholz, R. Y., & Fiocco, A. J. (2022). The effect of a brief mindfulness practice on perceived stress and sustained attention: Does priming matter? Mindfulness, 13(7), 1757–1768. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-022-01913-8

- van der Schalk, J., Fischer, A., Doosje, B., Wigboldus, D., Hawk, S., Rotteveel, M., & Hess, U. (2011). Convergent and divergent responses to emotional displays of ingroup and outgroup. Emotion, 11(2), 286–298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022582

- Wielgosz, J., Goldberg, S. B., Kral, T., Dunne, J. D., & Davidson, R. J. (2019). Mindfulness meditation and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 15, 285–316. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-021815-093423

- Wilkinson, R. A., & Chilton, G. (2017). Positive art therapy theory and practice: Integrating positive psychology with art therapy. Routledge.

- Williams, P. R. (2018). ONEBird: Integrating mindfulness, self-compassion, and art therapy. Canadian Art Therapy Association Journal, 31(1), 23–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/08322473.2018.1454687

- Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.concog.2010.03.014

- Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Gordon, N. S., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Effects of brief and sham mindfulness meditation on mood and cardiovascular variables. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 16(8), 867–873. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0321