Abstract

The study examined the Bird’s Nest Drawing (BND) of 14 adults who experienced child sexual abuse perpetrated by females, primarily their mothers. Descriptive analysis revealed the prevalence of insecure attachment and mainly an ambivalent representation. The drawings reflected vulnerability and under-protectiveness. Almost one-third of the drawings did not include caregiving and were suggestive of loneliness, abandonment, and rejection. When maternal caregiving was depicted, it was intrusive and characterized by a lack of separation, abandonment, or unsatisfying caregiving. The survivors’ narratives (n = 4) revealed themes of sadness, lack of protection, and vulnerability related to their mothers’ lack of competence. These findings suggest that the BND can serve as a valuable art therapy assessment tool to better understand attachment representations.

A growing number of studies have been devoted in recent years to child sexual abuse (CSA) by female perpetrators, but many issues remain underexplored. Masked by the widespread perception of the maternal role in nurturing and protecting their children, health and legal professionals tend to reject the notion that women in general, and mothers in particular, can sexually harm their children. Many professionals believe that incest is limited to fathers and their daughters. Some go so far as to state that if women commit sexual offenses, no actual harm is done since there is no male genital penetration. Others express compassion toward these women and minimize their conduct by referring to female perpetration as an “affair” or “relation.” Still, others view female perpetrators as strange, mad, or victims themselves (Colson et al., Citation2013). In many cases, active sexual abuse is obfuscated by parallel normative caregiving such as bathing, changing diapers, and dressing (Weinsheime et al., Citation2017).

These tendencies render female sexual crimes and incest marginal, silenced, and invisible and may explain why this abuse is underreported, understudied, and untreated (Kramer & Bowman, Citation2021). Nevertheless, a recent meta-analysis of 17 victimization surveys indicated prevalence rates of 11.6% (Cortoni et al., Citation2017). Victims’ surveys conducted in Germany and Australia yielded a prevalence rate of 9.9% (Gerke et al., Citation2020) and 11.6% (Cortoni, Citation2015), respectively. These data underscore the need to further understand the aftermath of abuse for the victims.

A few publications, most of which have been either case studies or qualitative analyses, have concentrated on the short and long-term consequences of this abuse on the victims, and have reported finding dissociative disorders (Deering & Mellor, Citation2011), a predisposition for depression (Curti et al., Citation2019; Deering & Mellor, Citation2011), social isolation, and phobias (Curti et al., Citation2019), misuse of addictive substances, suicidal ideation (Deering & Mellor, Citation2011), self-harm behaviors (Deering & Mellor, Citation2011), and difficulties in sexuality and sexualized behavior (Curti et al., Citation2019). One study noted disorganized attachment (Curti et al., Citation2019), which could help account for the behavioral, dissociative, and personality disorders described above.

Since attachment representations are internal, they cannot be directly observed. For this reason, indirect methods such as narrative production and drawings tasks designed to evoke attachment-related scripts are used to capture attachment representations (Psouni & Apetroaia, Citation2014). One such technique, which is in its early stages of development (Yoon et al., Citation2020), is the Bird’s Nest Drawing (BND; Kaiser, Citation1996). In an attempt to further validate the BND, the present study examined the characteristics of the BND in a clinical sample of female child sexual abuse survivors.

The Bird’s Nest Drawing Assessment (Kaiser, Citation1996)

The BND is an art-based technique grounded in Attachment Theory, which assesses forms of attachment representations. Attachment Theory posits that beginning in infancy and continuing throughout the lifespan, individuals’ mental health and capacity to form close relationships are intimately linked to early relationships with attachment figures who provide emotional support and protection (Bretherton & Munholland, Citation2008). Thus, infants’ experiences with their primary caregivers shape their representational models later in life. These “internal working models” reflect the extent to which young children feel valued and worthy of care and affection from others (model of the self), as well as the extent to which they generally perceive others to be available, accepting, and responsive (model of others) (Bowlby, Citation1980, Citation1969/1982). Children experiencing sensitive and responsive care are said to have a secure attachment representation characterized by closeness, trust in others, and adaptive strategies for managing stress. Their caregivers constitute a secure base from which to explore and a safe haven in times of distress (Ainsworth, Citation1989; Bowlby, Citation1969/1982).

In contrast, children classified as avoidant are considered to have experienced caregivers who rebuffed their distress signals and attempts at closeness. Because these children experience discomfort in close relationships and intimate situations, they tend to minimize their need for attachment-related signs that might otherwise prompt them to approach a caregiver later in life. Avoidant children tend to adopt a strategy of self-reliance. Children with anxious (ambivalent) attachment representations are considered to have experienced fluctuating caregiver responsiveness when seeking comfort. This volatile response prompts constant concern about the caretaker’s availability. Because they are highly vigilant about their attachment figure’s accessibility, these children exhibit a relational strategy characterized by intense attachment behaviors to elicit the attention of the caregiver, whom they perceive as unpredictably responsive (Cassidy, Citation1994; Main, Citation1990). Children with a disorganized attachment representation often experience a caregiver showing a mixture of terrified, helpless, inexplicable, contradictory, and fragmentary unexpected fluctuations in behavior when dealing with stress (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Citation2016).

In adulthood, clinicians often apply a 4-pronged autonomous, dismissing, preoccupied, or unresolved typology to classify adults’ relational attitudes on the Adult Attachment Interview (Main & Goldwyn, Citation1984). Individuals classified as having a secure state of mind maintain a balanced view of early relationships, value attachment relationships, and view attachment-related experiences as necessary to their development (Cassidy, Citation2001; Collins & Sroufe, Citation1999). By contrast, dismissing (avoidant) individuals are characterized by chronic attempts to “deactivate” or minimize activation of the attachment system (Cassidy, Citation2000). They avoid physical and emotional intimacy and, when facing stressful situations, tend to minimize expressions of distress and are unlikely to turn to or provide support for others (Edelstein & Shaver, Citation2004). Preoccupied (anxious) individuals are seen as enmeshed in their relationships. They heighten their expression of distress and find it challenging to cope independently or form relationships in which their autonomy is maintained (Cassidy & Berlin, Citation1994). They are hyper-vigilant toward attachment figures and attachment-related concerns and are easily distressed by brief separations or stressful events (Mikulincer et al., Citation2006). Finally, disorganized individuals are concerned with loss or trauma. Experiencing caregiving that is characterized by a mixture of terrified, helpless, inexplicable, contradictory, and fragmentary unexpected fluctuations behavior in dealing with stress, these individuals show substantial inconsistency and odd behavior that alternates between aggression and detachment, rage, and lack of adaptation (Lyons-Ruth & Jacobvitz, Citation2016).

Much research has shown that maltreated children have higher rates of insecure attachment than non-maltreated children (e.g., Cyr et al., Citation2010; Stronach et al., Citation2011). One well-established technique to assess these representations is Kaplan and Main’s (Citation1986) coding system for analyzing children’s family drawings. Another, less well-validated, art-based technique to assess attachment security in children and adults is the Bird’s Nest Drawing (BND) (Kaiser, Citation1996). Based on the assumption that the metaphor of the bird’s nest elicits attachment experiences, the drawing is thought to reflect the artmaker’s internal representation of caregiving (Sheller, Citation2007).

In early research, researchers used a sign-based approach to classify these drawings. Based on the presence or the absence of specific indicators, researchers investigated the links between the 11 characteristics of the BND drawings and various measures of attachment security. Nevertheless, out of the 11 markers, these studies only reported associations between individuals’ attachment security and four indicators: the depiction of birds, a family of birds, a securely placed nest, and the use of colors, especially green or brown (Francis et al., Citation2003; Kaiser, Citation1996). For instance, in Kaiser’s original study of the Bird’s Nest Drawing (Kaiser, Citation1996), BNDs were collected from a sample of mothers (n = 41). Using the Attachment to Mother (ATM) scale of the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA) (Armsden & Greenberg, Citation1987), the researchers divided the participants into high and low-ATM groups. The high-ATM group depicted birds in their drawings significantly more often than the low-ATM group, whereas the low-ATM group often depicted a tilted nest without birds. Francis et al. (Citation2003) compared the BNDs of adults with substance abuse disorders (n = 43) to patients in a comparison group from a medical clinic who had no substance abuse disorders (n = 27). Participants completed a BND, a story about their BND, and Bartholomew and Horowitz’s (Citation1991) Relationship Questionnaire. Analysis of the drawings for the entire sample indicated that securely attached participants drew more birds, drew an entire bird family, used four or more colors, drew the nest in profile (not tilted), and used green as the dominant color.

Likewise, Harmon-Walker and Kaiser (Citation2015) examined the associations between attachment security as reflected in the Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire (ECR; Bartholomew & Shaver, Citation1998) and the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, Citation1987) in a sample of 136 undergraduate students. After dividing the sample into securely and insecurely attached groups, the study found associations between depicting a family of birds in participants with high IPPA scores and between bottomless nests in participants with low ECR scores.

To further validate the assessment, researchers have suggested implementing a more global approach for rating BND drawings using a general impression (Bouteyre et al., Citation2022; Goldner, Citation2014; Harmon-Walker & Kaiser, Citation2015). This approach was selected because integrative ratings may be better suited than discrete indicators to reflect mental organization (Goldner, Citation2014; Harmon-Walker & Kaiser, Citation2015).

For instance, Kaiser and Deaver (Citation2009) reviewed a series of clinical observations and small research studies and concluded that using general impressions along with groups of indicators is a more valid approach than examining distinct indicators as signifying attachment representations. Likewise, Harmon-Walker and Kaiser (Citation2015) divided the BND into four categories of attachment organization and searched for correlations between attachment categories identified in the drawings and participants’ attachment security as reflected in the Experiences in Close Relationships Questionnaire (ECR; Bartholomew & Shaver, Citation1998) and the Inventory of Parent and Peer Attachment (IPPA; Armsden & Greenberg, Citation1987) scores. The researchers reported a significant association between attachment security with mother (ATM) subscale score and secure BNDs. However, there were no associations between overall impression ratings and the ECR scores.

In a reanalysis of Harmon-Walker & Kaiser’s data, Yoon et al. (Citation2020) examined the construct validity of the BND. The authors analyzed the quality of the TCC items’ skewness and interrater reliability, the internal reliability of the BND’s components (high-quality TCC items, OIF, and story rating scales), and the correlations between the TCC items, OIF classifications, and the attachment scores. The researchers showed good psychometric properties for four of the 11 indicators and the OIF and suggested the need to further collect data from clinical populations.

Finally, Goldner (Citation2014) found positive associations between secure (versus insecure) attachment classifications on family drawings and BND classifications (secure versus insecure) in a sample of 81 elementary-school children. A correlation was also found between children’s attachment security scores on Kerns et al.’s (Citation1996) Security Scale and the optimism subscale of the BND that contains aspects of adequate caregiving behavior and emotional investment in the drawing. Other studies have explored the theme of deprivation, threats to the family, and abandonment in narratives associated with the BNDs, using content analysis of the stories (Bouteyre et al., Citation2022; Sheller, Citation2007).

These preliminary findings hint at the potential of the BND to detect individuals’ attachment security. Nevertheless, because the BND is at an earlier stage of development, further investigations are needed to strengthen its validation. The current study, thus, implemented both approaches to examine the validation of the BND as a projective tool to shed light on attachment representations in a clinical sample of adult survivors who experienced child sexual abuse by females. We hypothesized that most drawings would be classified as insecure by depicting inadequate caregiving, unprotected nests, and abandonment. We also predicted that the participants’ associated narrative would confirm these trends.

Method

Research Design

The study employed a quantitative design with limited qualitative means. A cross-sectional study using bird’s nest drawings and short narratives was used. Ethical approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Welfare and Health Sciences at the University of Haifa (Approval number 163/22).

Participants

Fourteen participants (one man) participated in this study. The participants were recruited using a snowball technique based initially on personal connections, who then suggested other possible participants, and on a convenience sampling design where advertisements were posted on social media and at treatment centers. The participants ranged in age from 21 to 50. Ten of the participants were subjected to incest by their mothers. Eight abusive acts began between the ages of 6–12, whereas the rest started in early childhood. Twelve of the abuses continued for three years or more. Five participants were also sexually assaulted by men during the same period women abused them. Thirteen participants were diagnosed with C-PTSD. At the time of the study, nine participants were not involved in romantic relationships, and six had children.

Procedures

After signing consent forms explaining the study’s aims, the participants were asked to make a BND with no time limitations on an A4 sheet using colored markers and to provide a short narrative about the drawings independently in their home environment. To better understand the inner experience of the participant, the participants provided short narratives for the drawings. We based this request on the assumption that generating storytelling can shed light on how humans experience the world (Goldner et al., Citation2021).

Validity

The two authors, professional art and drama therapists, rated the drawings and extracted the central themes of the narratives separately. Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Kappa values were used to assess inter-rater reliabilities regarding the graphic indicators (Kappa values ranged from .83 to 1.00, p = .000) and categorizations (Kappa = .83, p = .000).

Data Analysis

We based the analysis of the drawings on the BND Two Category Checklist (BND-TCC; Kaiser, Citation2012) and the BND Four Category Overall Impression Form (BND-OIF; Kaiser, Citation2012) as described in Harmon-Walker and Kaiser (Citation2015). The BND-TCC (Kaiser, Citation2012) assesses 11 graphic indicators as present or absent in the drawing: one or more birds, a bird family, an environment, four or more colors, green or brown dominates, the nest is tilted 45 degrees or more such that it appears that the contents may fall out, there is no bottom to the nest, the nest is in a vulnerable position, there are restarts, erasures, or areas crossed out, and there are unusual, bizarre, incoherent, or disorganized elements or approaches to the drawing. Based on previous work (Goldner, Citation2014), we added three additional indicators that characterized various types of caregiving and formed the basis of attachment representations: depicting adequate caregiving interaction (feeding, incubation, observation), depicting intrusiveness, lack of separation, and abandoning caregiving, and the absence of caregiving behavior.

In addition, the drawings were rated based on the operational definitions ascribing the four categories of attachment classifications to the four groups of drawing characteristics with which they are theoretically associated. The drawings of securely attached participants are characterized by a cheerful, realistic, and calm impression that communicates a generally welcoming quality. The image is organized, containing a realistic environment and adequate caregiving behavior. In some cases, green dominated the drawing.

By contrast, the overall impression characterizing the drawings of dismissing attached participants is isolation or emptiness, an absence of connectedness, and an absence of caregiving. The nest is empty or may contain eggs but no birds (other than outlines). Trim or no color is used, and little or no environment is drawn. The nest may be tilted or lack a bottom. An overall impression of vulnerability characterizes the drawings of preoccupied attached participants. The nest appears unsafe or unprotected, and its contents are unusually large or small. Brown is often the dominant color. The drawing crowded the edges of the paper or had a quality of excessive cuteness or sweetness. Finally, drawings of disorganized fearful participants generate an overall irrational, disorganized, strange, and/or threatening impression, including strange marks, irrational elements, unfinished objects, and/or scratched-out objects. Analyzing the narratives was made based on the narratives’ central theme and valance.

Results

Quantitative Analysis of the Drawings

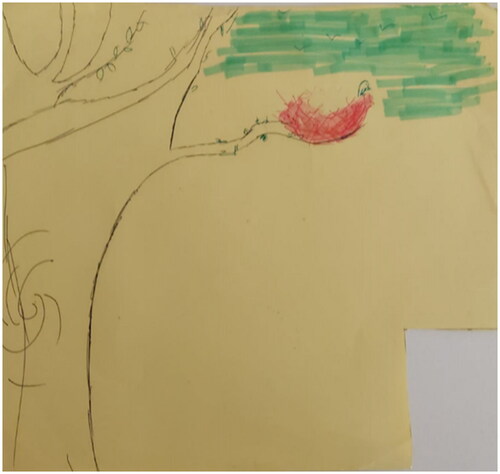

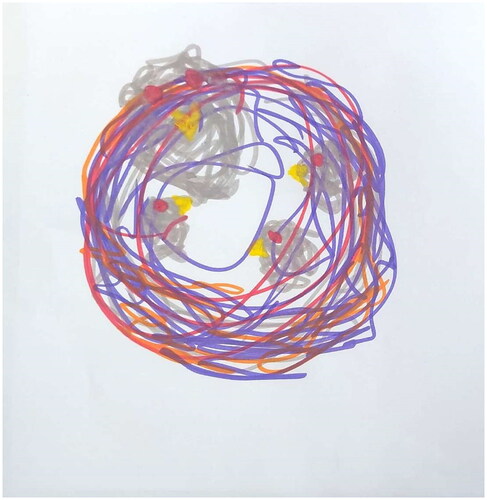

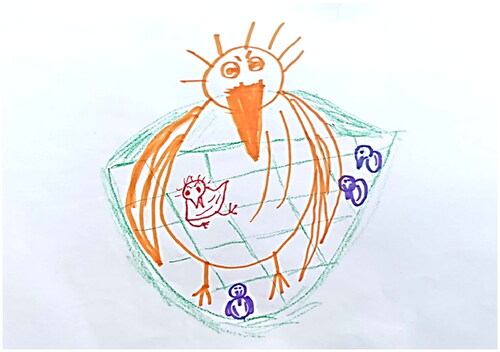

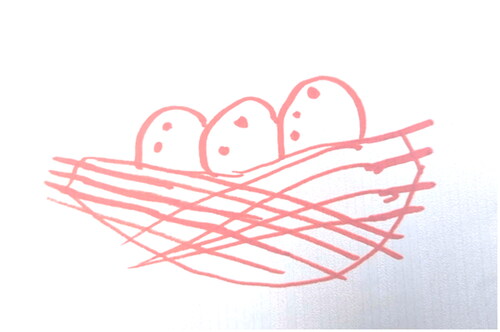

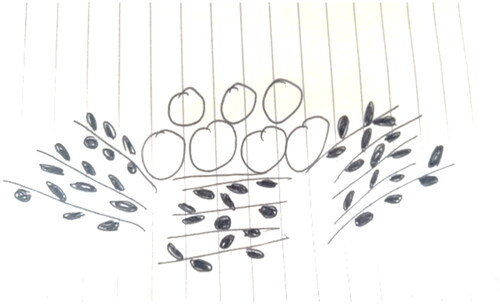

As expected and shown in , almost all of the drawings corresponded to insecure attachment representations (n = 13, 93%), and the majority were classified as preoccupied (n = 8, 57%) (). Three drawings were classified as dismissing (21%) (), and two were disorganized (14%) (). Only one drawing (7%) was classified as secure.

Table 1. The BND Overall Impression Form (BND-OIF) Categories

An in-depth examination () indicated that although most of the drawings included birds (n = 11.79%) and families of birds (n = 7.50%), the vast majority did not include adequate caregiving (n = 1.93%), and the overall impression was that of vulnerability and under-protectiveness. In six drawings (43%), the nest was either drawn in a precarious position or lacked a bottom. In two other drawings, it was slanted and almost falling (). Almost no adequate caregiving was depicted (). When maternal caregiving was depicted, it was intrusive and characterized by a lack of separation (n = 3.21%), abandonment (n = 3.21%), or unsatisfying (), leaving the baby birds hungry (n = 3.21%). No caregiving appeared in almost one-third of the drawings, instilling feelings of loneliness, abandonment, and rejection (n = 4.29%) ().

Table 2. Prevalence of the BND Two Category (BND-TCC) Indicators

Narrative Analysis: Loneliness, Vulnerability, and Emotional Abandonment

Four participants provided narratives about their drawings. These supported the intrusiveness, lack of protection, vulnerability, and emotional abandonment identified in the drawings. For example, the narrative and the drawing of T., whose mother abused her between the ages of 13 to 18, exemplified a lack of protectiveness. The narrative illustrated the psychological control enacted by her mother that revolved around satisfying her mother’s need to ease her loneliness while instilling feelings of self-doubt and insecurity in the baby bird. She narrated:

Once upon a time, a little bird wanted to fly away. Every day she would sit on the edge of the nest, almost falling off most of the time sitting. She saw all the other birds flying in the sky every time she watched. She wanted to be like them, but she was afraid. Her mother was afraid she would leave the nest and told her she was better off in the safe nest. One day there was an earthquake, and the nest started to shake. She had no choice but to fly off.

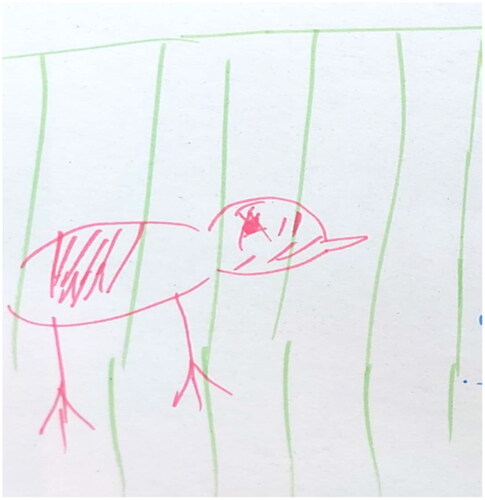

These feelings of loneliness, disconnection, and abandonment were also expressed in A’s drawing (whose mother abused her from the age of six throughout adolescence) and in K’s drawing (whose mother abused her from the age of three throughout adolescence) that depicted an empty nest, and no interaction, caregiving or vitality (see and ). Their narratives illustrate this neglect and an unfulfilled expectation of parental care:

“Once upon a time, there were three eggs in a nest on a high tree waiting for the right time to hatch. Winter came, and summer came, and the right time never came” (A); “She (the mother bird) came yesterday. She left them branches and a few leaves to cushion the nest and then flew away” (K).

Discussion

The current study examined the potential of the BND to determine attachment classifications in a sample of individuals who experienced child sexual abuse by female perpetrators. As expected, most drawings were rated as insecure, with an ambivalent/preoccupied classification characterized by intense vulnerability and intrusiveness. These findings may be accounted for by the inter-generational transmission of an insecure attachment style through abusive and abusive parenting behaviors and child maltreatment (Bartlett et al., Citation2017; Berlin et al., Citation2011; Stronach et al., Citation2011). Studies concentrating on the characteristics of female offenders often reveal a history of child maltreatment (Christopher et al., Citation2007). Studies have also shown that these offenders have a significant lack of self-esteem and shame-ridden personalities that can lead to pathological parent-child dynamics and children’s attachment insecurity (Cicchetti & Doyle, Citation2016). The dominance of insecure ambivalent/preoccupied attachment classification in the drawings may also be attributed to the confusion created by the fact that these abusive acts were performed during everyday caregiving, such as bathing and dressing (Weinsheime et al., Citation2017). These acts, which are part of normative caring routines, place the children in a double bind in which their attachment figure simultaneously serves as their source of safety and caregiving but also fear and harm (Cicchetti & Doyle, Citation2016). This paradox may help account for the high vulnerability and the absence of a protective parental figure that characterized the preoccupied-ambivalent drawings and the oddness of the drawings that corresponded to a disorganized representation.

In some drawings rated as ambivalent, the survivors portrayed a lack of separation in which the baby birds were depicted as an extension of the mother bird’s body and as objects to satisfy the mothers’ psychological needs for intimacy and value. In their narratives, the baby birds were isolated from the outside world and experienced physical and emotional neglect. These findings may represent narcissistic caregiving characterized by the parent’s inability to be aware of the children’s needs (Määttä & Uusiautti, Citation2020) and the internalization of entangled and enmeshed representations of intimate relationships. Finally, three drawings were classified as dismissing and were characterized by limited emotionality, a lack of vitality as well as interaction, and isolation. These drawings may represent the survivors’ internalization of their attachment figures as unreliable and uncaring who denied their attachment needs while distancing themselves from others and exhibiting restricted expressions of emotionality (Collins et al., Citation2002).

Practical Implications

The current study exemplified how the BND can provide art therapists with information regarding the lack of protection, vulnerability, intrusiveness, and abandonment of survivors of childhood sexual abuse who were abused by women. This is especially important given the intergenerational transition of insecure attachment organization in maltreated populations and survivors’ tendency to silence the abuse.

Limitations

This study has several limitations related to the small number of participants, the sampling method, and the sample size that may hamper generalization. Future studies should consider using a larger sample and random recruitment to validate the results. The sample was also recruited in Israel. Future studies should explore survivors from more diverse backgrounds. In addition, because experience with art and drawing materials can confound art therapy assessment ratings, the lack of information related to participants’ experience with art materials may have influenced the validity of the ratings. Finally, the current study is based on participants’ drawings and narratives. Thus, future studies could consider adding an established attachment measure to strengthen the validity of the results.

Conclusions

Despite these limitations, the findings modestly point to the potential of BND to shed light on attachment organization and the representations of parent-child relationships in clinical populations. Although studies suggest that further research is required to validate the BND as an assessment of attachment representations to inform treatment planning and clinical practice.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Limor Goldner

Limor Goldner, PhD, is an Associate Professor, and Ortal Herzig Reingold, MA, is a Graduate Psychodrama Student in the School of Creative Arts Therapies, Faculty of Social Welfare and Health Sciences, University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel.

References

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. The American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.70

- Armsden, G. C., & Greenberg, M. T. (1987). The inventory of parent and peer attachment: Individual differences and their relationship to psychological well-being in adolescence. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 16(5), 427–454. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02202939

- Bartholomew, K., & Horowitz, L. M. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61(2), 226–244. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.61.2.226

- Bartholomew, K., & Shaver, P. R. (1998). Methods of assessing adult attachment: Do they converge? In J. A. Simpson, & W. S. Rholes (Eds.), Attachment theory and close relationships (pp. 25–45). The Guilford Press.

- Bartlett, J. D., Kotake, C., Fauth, R., & Easterbrooks, M. A. (2017). Intergenerational transmission of child abuse and neglect: Do maltreatment type, perpetrator, and substantiation status matter? Child Abuse & Neglect, 63, 84–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.11.021

- Berlin, L. J., Appleyard, K., & Dodge, K. A. (2011). Intergenerational continuity in child maltreatment: Mediating mechanisms and implications for prevention. Child Development, 82(1), 162–176. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01547.x

- Bouteyre, E., Halidi, O., & Despax, J. (2022). Childlessness among adopted women: A study of the role of attachment through Bird’s Nest Drawings. Adoption & Fostering, 46(1), 41–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/03085759221081350

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Attachment and loss: Vol. 3. Loss and sadness. Hogarth Press and the Institute of Psycho-Analysis.

- Bowlby, J. (1982). Attachment and loss, Vol. 1: Attachment. Basic Books. (Original work published 1969)

- Bretherton, I., & Munholland, K. A. (2008). Internal working models in attachment relationships: Elaborating a central concept in attachment theory. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 102–129). Guilford Press.

- Cassidy, J. (1994). Emotion regulation: Influences of attachment relationships. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59(2–3), 228–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5834.1994.tb01287.x

- Cassidy, J. (2000). Adult romantic attachments: A developmental perspective on individual differences. Review of General Psychology, 4(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.4.2.111

- Cassidy, J. (2001). Truth, lies, and intimacy: An attachment perspective. Attachment & Human Development, 3(2), 121–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730110058999

- Cassidy, J., & Berlin, L. J. (1994). The insecure/ambivalent pattern of attachment: Theory and research. Child Development, 65(4), 971–991. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00796.x

- Christopher, K., Lutz-Zois, C. J., & Reinhardt, A. R. (2007). Female sexual-offenders: Personality pathology as a mediator of the relationship between childhood sexual abuse history and sexual abuse perpetration against others. Child Abuse & Neglect, 31(8), 871–883. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.02.006

- Cicchetti, D., & Doyle, C. (2016). Child maltreatment, attachment and psychopathology: Mediating relations. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 89–90. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20337

- Collins, N. L., Cooper, M. L., Albino, A., & Allard, L. (2002). Psychosocial vulnerability from adolescence to adulthood: A prospective study of attachment style differences in relationship functioning and partner choice. Journal of Personality, 70, 965–1008. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.05029

- Collins, W. A., & Sroufe, L. A. (1999). Capacity for intimate relationships. The development of romantic relationships in adolescence. In W. Furman, B. B. Brown, & C. Feiring (Eds.), The development of romantic relationships in adolescence (pp. 125–147). Cambridge University Press.

- Colson, M. H., Boyer, L., Baumstarck, K., & Loundou, A. D. (2013). Female sex offenders: A challenge to certain paradigms. Meta-analysis. Sexologies, 22(4), e109–e117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2013.05.002

- Cortoni, F. (2015). What is so special about female sexual offenders? Introduction to the special issue on female sexual offenders. Sexual Abuse, 27(3), 232–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063214564392

- Cortoni, F., Babchishin, K. M., & Rat, C. (2017). The proportion of sexual offenders who are female is higher than thought: A meta-analysis. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 44(2), 145–162. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854816658923

- Curti, S. M., Lupariello, F., Coppo, E., Praznik, E. J., Racalbuto, S. S., & Di Vella, G. (2019). Child sexual abuse perpetrated by women: Case series and review of the literature. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 64(5), 1427–1437. https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.14033

- Cyr, C., Euser, E. M., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & Van Ijzendoorn, M. H. (2010). Attachment security and disorganization in maltreating and high-risk families: A series of meta-analyses. Development and Psychopathology, 22(1), 87–108. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579409990289

- Deering, R., & Mellor, D. (2011). An exploratory qualitative study of the self-reported impact of female-perpetrated childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 20(1), 58–76. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2011.539964

- Edelstein, R. S., & Shaver, P. R. (2004). Avoidant attachment: Exploration of an oxymoron. In D. Mashek & A. Aron (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 397–412). Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Francis, D., Kaiser, D., & Deaver, S. (2003). Representations of attachment security in the Bird’s Next Drawings of clients with substance abuse disorders. Art Therapy, 20(3), 125–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2003.10129571

- Gerke, J., Rassenhofer, M., Witt, A., Sachser, C., & Fegert, J. M. (2020). Female-perpetrated child sexual abuse: Prevalence rates in Germany. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 29(3), 263–277. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538712.2019.1685616

- Goldner, L. (2014). Revisiting the bird’s nest drawing assessment: Toward a global approach. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(4), 391–399. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.06.003

- Goldner, L., Lev-Wiesel, R., & Binson, B. (2021). Perceptions of child abuse as manifested in drawings and narratives by children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 562972. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.562972

- Harmon-Walker, G., & Kaiser, D. H. (2015). The Bird’s Nest Drawing: A study of construct validity and interrater reliability. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 42, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.12.008

- Kaiser, D. H. (1996). Indications of attachment security in a drawing task. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 23(4), 333–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0197-4556(96)00003-2

- Kaiser, D. H. (2012). Kaiser’s Bird’s Nest drawing two category checklist and four category overall impression manual [Unpublished manuscript]. Drexel University.

- Kaiser, D. H., & Deaver, S. (2009). Assessing attachment with the bird’s nest drawing: A review of the research. Art Therapy, 26(1), 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2009.10129312

- Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1986). Instructions for the classification of children’s family drawings in terms of representation of attachment [Unpublished manuscript]. University of California.

- Kerns, K. A., Klepac, L., & Cole, AKay. (1996). Peer relationship and preadolescents’ perceptions of security in child mother relationship. Developmental Psychology, 32(3), 457–466. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.32.3.457

- Kramer, S., & Bowman, B. (2021). Confession, psychology, and the shaping of subjectivity through interviews with victims of female-perpetrated sexual violence. Subjectivity, 14(1–2), 73–93. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41286-021-00117-0

- Lyons-Ruth, K., & Jacobvitz, D. (2016). Attachment disorganization from infancy to adulthood: Neurobiological correlates, parenting contexts, and pathways to disorder. In J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (3rd ed., pp. 667–695). Guilford.

- Määttä, M., & Uusiautti, S. (2020). My life felt like a cage without an exit’–narratives of childhood under the abuse of a narcissistic mother. Early Child Development and Care, 190(7), 1065–1079. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1513924

- Main, M. (1990). Cross-cultural studies of attachment organization: Recent studies, changing methodologies, and the concept of conditional strategies. Human Development, 33(1), 48–61. https://doi.org/10.1159/000276502

- Main, M., & Goldwyn, R. (1984). Predicting rejection of her infant from mother’s representation of her own experience: Implications for the abused-abusing intergenerational cycle. Child Abuse & Neglect, 8(2), 203–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/0145-2134(84)90009-7

- Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Slav, K. (2006). Attachment, mental representations of others, and gratitude and forgiveness in romantic relationships. In M. Mikulincer & G. S. Goodman (Eds.), Dynamics of romantic love: Attachment, caregiving, and sex (pp. 190–215). Guilford.

- Psouni, E., & Apetroaia, A. (2014). Measuring scripted attachment-related knowledge in middle childhood: The Secure Base Script Test. Attachment & Human Development, 16(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2013.804329

- Sheller, S. (2007). Understanding insecure attachment: A study using children’s bird nest imagery. Art Therapy, 24(3), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129427

- Stronach, P. E., Toth, S. L., Rogosch, F., Oshri, A., Manly, J. T., & Cicchetti, D. (2011). Child maltreatment, attachment security, and internal representations of mother and mother-child relationships. Child Maltreatment, 16(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077559511398294

- Weinsheime, C. C., Woiwod, D. M., Coburn, P. I., Chong, K., & Connolly, D. A. (2017). The unusual suspects: Female versus male accused in child sexual abuse cases. Child Abuse & Neglect, 72, 446–455. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.003

- Yoon, J. Y., Betts, D., & Holttum, S. (2020). The bird’s nest drawing and accompanying stories in the assessment of attachment security. International Journal of Art Therapy, 25(2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2019.1697306