Abstract

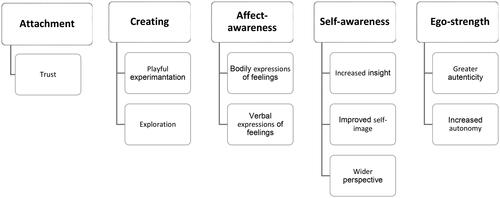

In order to provide clinical utility for research of how art therapists perceive clients’ inner change, the authors created a structured observational framework. This note-taking and assessment consist of five themes and sub-themes: Therapeutic Alliance, Creating, Affect-Awareness, Self-Awareness, and Ego-Strength. The framework was designed to be clinically-friendly, adaptable to various settings, and assist communication with both patients and relevant healthcare professionals.

Since the introduction of evidence-based medicine in the 1990s in Sweden, there is a requirement to clearly communicate the results of art therapy. Much has already been written about the client’s change through art therapy based on different theoretical perspectives, and a large number of different assessment instruments and tests have been constructed to confirm its usefulness (Pénzes et al., Citation2014). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no practical, observational framework for assessing the development of inner change during and after art therapy.

In our earlier qualitative study, we defined the concept of inner change as a deeper psychological structural change, which is permanent and differs from a more superficial, transitory change (Holmqvist et al., Citation2017). The art therapists who participated answered two open-ended questions in their own words: Can you describe how you perceive inner change in a client, and can you describe one or more situations when you perceived an inner change in a client? We discovered five themes and associated sub-themes: Attachment, Creating, Affect-awareness, Self-awareness, and Ego-strength (). The purpose of this paper is to make use of our findings in order to present a practical observational framework for assessing the development of the client’s inner change during and after art therapy.

Construction of the Observational Framework

Art therapists in Sweden are influenced by various theories but most of them have knowledge of psychodynamic theory and use psychodynamic concepts in describing clients’ psychological inner change. This was also the case with the art therapists who participated in the above-mentioned study. In addition, they were familiar with the triangular relationship theory, i.e., the client, the therapist, and the image, as well as the creative process (Schaverien, Citation2000). In order to adapt our research into a practical note-taking tool, we chose to expand on the five themes in relation to theories of psychodynamic emotional development and art therapy.

Attachment refers to the emotional relationship, which is based on the early relation between caregiver and child (Bowlby, Citation1988). The individual attachment style can be secure, insecure-ambivalent, insecure-avoidant, or insecure-disorganized (Ainsworth et al., Citation1978; Main & Solomon, Citation1993), which often becomes visible in art therapy through the way the art material is used (Corem et al., Citation2015; Snir et al., Citation2017). Clients with a secure attachment style often find art creation joyful and stimulating, while those with an insecure attachment pattern exhibit a tendency to resist and react negatively to the art material (Corem et al., Citation2015). Haeyen and Hinz (Citation2020) claim that the individual attachment style can be observed within the first 15 minutes of an art therapy session, as the client soon exhibits emotional regulation strategies and favored components in accordance with the Expressive Therapies Continuum (ETC), namely cognitive/symbolic, perceptual/affective, and kinesthetic/sensory levels, linked at the creative level. A therapeutic alliance built on trust and security is established as the client and the art therapist together formulate the tasks, framework, and individual goals of the therapy (Haeyen et al., Citation2018; Hinz, Citation2019). De Witte et al. (Citation2021) underlined the importance of both a strong therapeutic alliance and a safe environment for clients’ processes of change. As the client and the therapist subjectively share an experience and feeling that is usually implicit and nonverbal, it enables a very specific in-depth relationship, called intersubjectivity (Skaife, Citation2001). Rankanen (Citation2021) believes that the therapeutic working alliance is based on intersubjective actions that change from attunement to misattunement and reattunemnt.

Creating refers to the creative process where the client uses different art materials to transfer thoughts, feelings, and experiences into an image. Expressing their inner life non-verbally in an image enables the client to exhibit feelings that may not be easily verbalized (De Witte et al., Citation2021). Hinz (Citation2019) pays particular attention to the aha moments of self-realization in which surprised clients understand something new about themselves that was previously unknown. Playful experimentation and playfulness are a state of spontaneous and carefree creation, which is not primarily focused on producing a product. Playfulness is an important ingredient of art therapy, as it can help the client befriend different artistic materials, overcome barriers to creativity, and avoid being overwhelmed by affects and feelings (Hinz, Citation2019). Rankanen (Citation2021) stresses the importance of playing together with the image in the triangular relationship to counteract compliance or resistance. Winnicott (Citation1971) has suggested that play is a means of reaching the authentic, creative, less defended part of a person’s personality, what he calls the true self. In the therapeutic relationship the art material can be raised from its concrete materiality and obtain a symbolic meaning in an image, which can be explored and understood (Isserow, Citation2013). Exploration implies looking together, which is more or less a matter of course in art therapy (Isserow, Citation2008). Betensky (Citation1995) emphasized the significance of the question: what do you see? to emphasize that the art therapist must help the client to understand and communicate through the image.

Affect-awareness means that clients are aware and observant of their bodily reactions, the affects, and are able to identify them as emotions or feelings. It is crucial to understand oneself and to be understood that the emotions are experienced consciously, that one can tolerate them and communicate them non-verbally and verbally (Monsen et al., Citation1996). As Shouse (Citation2005) pointed out, feelings are subjective either consciously or subconsciously. According to Tomkins (Citation1984), the basic affects are interest, joy, surprise, disgust, anger, grief, fear, and shame. Emotions and feelings constitute the basis for thoughts, decisions, and actions and are the primary system of motivation. In art therapy, sharing an affect in an image may promote clients’ awareness of emotions (Isserow, Citation2008). Increased awareness of emotions may in turn promote affect-tolerance and affect-regulation (Haeyen et al., Citation2015). The vitality affect differs from the basic affects in that it is an inner psychological movement that emerges in the individual’s meeting with dynamic, stimulating events (Stern, Citation2010). According to Stern, creative activities like art, music, and dance can set the patient’s inner life in motion and may evoke vitality affects that lead to revitalization, which provides energy, meaning, and a sense of being alive. An important part of affect-awareness is the verbal expression of feelings, which requires the client to translate body sensations into an image and then into words (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016). The client has to discover the movement between non-verbal and verbal levels and understand that communication can appear in many different ways (Hinz, Citation2019). Non-verbal expression of feelings and verbally sharing the creative experience in art therapy will counteract depression and alexithymia, a condition characterized by an inability to recognize, understand, and describe emotions (Nan & Ho, Citation2014).

Self-awareness means being aware of one’s own way of being and how one is perceived by others. As the image in art therapy is seen as visualization of the client´s inner life (Case & Dalley, Citation2014), self-awareness will increase in a process from implicit to explicit self-expression (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016). Increased insight and all changes in art therapy are dependent on the client’s ability to achieve a reflective distance to the image and the creative process (Kagin & Lusebrink, Citation1978). This means the client has to achieve a cognitive distance from the emotions that occur as a result of art creating, thereby making it possible to think about and reflect on the deeper meaning of the creative expression (Hinz, Citation2019). Insight into one’s own emotions, the emotions of others, and distinguishing between them is called mentalization (Fonagy & Target, Citation1997), where art therapy has particularly been highlighted as a method that seems to promote mentalization processes (Springham et al., Citation2012). Springham et al. (Citation2012) state that mentalization processes are promoted by creating images at a slow pace, as thoughts and feelings can be organized, after which the images can gradually be transformed into words and shared with a therapist or group members. In art therapy is it possible to see things more clearly through an image, which leads to questioning a typical way of looking as well as discovering new ways of looking at a situation or at one’s own person (Hinz, Citation2019). Clients have reported that art therapy started a process of change that promoted improved self-image, which means increased acceptance and a more realistic view of oneself (Rankanen, Citation2016). In the same way artistic self-expression and reflection on problematic feelings stabilized the self-image of clients diagnosed with Personality Disorders (Haeyen et al., Citation2020). Widening perspectives is possible in art therapy by creating an image and then changing it, which can give clients the opportunity to look at the reality from different perspectives and accept a more adaptive point of view (Czamanski-Cohen & Weihs, Citation2016). However, Isserow (Citation2013) underlines the fact that in the end, it is the client´s ability to take another standpoint that enables therapeutic changes to occur.

Ego-strength consists of mental functions and processes that help the individual to manage life experiences (Guntrip, Citation2018). Examples of ego-functions are impulse regulation, self-knowledge, thinking ability, and perception of reality that involves separating the internal life from the external. In art therapy ego-functions may be strengthened by overcoming difficulties and postponing needs by, for example, finishing an artwork (Case & Dalley, Citation2014). When clients are strong enough to be true to their own personality, values, and spirit, regardless of their situation, they will show greater authenticity, which in Winnicott’s (Citation1971) words can be described as having a true self. Winnicott argued that the individual will develop a true or false self, depending on the relationships experienced when growing up and that repairing and changing imply going from a false self to a true self. A false self is associated with shame, which in art therapy can be reduced through the creative experience, reflections on the self-image, and changes toward a more authentic and true self (Hinz, Citation2019). Increased autonomy is not always described specifically in art therapy but can hide behind concepts such as coping ability, manageability (Shafir et al., Citation2020) or ability to make decisions (Blomdahl et al., Citation2022). One exception is a group of clients diagnosed with Personality Disorders in the study by Haeyen et al.(Citation2020). They described the ability to make own choices and increased autonomy as one of several areas positively affected by art therapy. On a general level, creating seems to maintain and strengthen autonomy, promote coping resources, and help the individual to find a sense of control in a situation experienced as chaotic (Braus & Morton, Citation2020).

Observational Framework

From our review of how the five themes of inner change may present in art therapy, we designed an observational framework note-taking form (). One alteration we made pertained to the theme of attachment. We broadened the area by re-naming it as therapeutic alliance, based on the sub-themes of attachment, trust, and interactive relationship (Holmqvist et al. Citation2017).

Table 1. Observational Framework of Developmental Inner Change

Table 1. Continued

Each theme is presented as a chart that includes sub-theme definition, blank space for an initial general observation of the client, and three developmental stages. In these boxes, examples of changes are presented, with space for the therapist’s notes and date. The developmental stages were organized based on the authors’ knowledge and experience of psychodynamic psychotherapy and art therapy. Therefore, to use this framework effectively, it should be used by a properly trained art therapist who is familiar with the theories of psychodynamic emotional development.

Reference Groups

During the development of the observational framework, seven trained art therapists in Sweden were asked to review the framework on two occasions. First, all seven were asked to give their views on the initial version. Six perceived the framework positively but pointed out the need for clarification of the different levels and one therapist was doubtful about an ongoing evaluation. When the framework had been revised in accordance with the suggestions, four of the most experienced art therapists reviewed it again to evaluate usability. They assessed the framework as user-friendly. One also mentioned that it may even lead to a better understanding of the clients’ problems.

Instructions for Using the Observational Framework

After the first two or three therapy sessions the art therapist assesses the client’s behavior and psychological status in relation to each area and to the vertically presented sub-themes. These initial observations can be briefly noted in the first observation box for each sub-theme. At the following evaluation, it may be appropriate to share the first evaluation with the client and at the same time make a preliminary plan with a timeframe and goals for continued art therapy. Furthermore, the client and the art therapist can decide together how often the follow-up with the framework should take place and whether they should complete it together. The decision can be reviewed and changed during the therapy. The time between follow-ups may vary, depending on whether the client is undergoing a crisis, has deeper psychological problems or severe mental illness with disabilities. The following follow-up intervals are suggested but may be changed depending on the client’s status and situation:

Short treatment time with evaluation every few weeks, for example due to a crisis in connection with grief, less complicated trauma, or physical problems.

Longer treatment time with evaluation every few months, for example due to the need for behavioral change, increased self-awareness, or mild depression.

Several years of treatment with evaluation at 6-month intervals, for example in cases of severe mental illness such as affective disorder or psychosis, deep trauma, or severe crisis.

Usability of the Observational Framework

This observational framework is intended for individual art therapy but not delimited to a specific art therapeutic institution or for a special group of clients. It is intended for use in different organizations, where art therapists want to obtain a structured evaluation of the clients’ inner change. It intentionally does not contain any descriptions of reduced symptoms or behavioral changes in everyday life, as the focus is on the lasting inner change that takes place on a psychologically deeper level over time. However, in the case of a successful therapy outcome, both symptoms and everyday activities will probably be affected in a positive direction.

This framework describes an ongoing process where the client moves from one stage to another, characterized by an elusive dynamic interaction between the areas and sub-themes. Therefore, the client’s inner change cannot be described solely based on the areas of affect-awareness, self-awareness, and ego-strength, because change is also manifested in attachment and creation, where the quality of attachment has an impact on creation. It can also be assumed that a positive therapeutic working alliance is linked to a better relationship between the client and the art medium, or vice versa, where creating may give a positive therapeutic alliance (Bat Or & Zilcha-Mano, Citation2019).

The framework is intended to show a client’s development in three steps. It is not intended to describe the natural back-and-forth movement in a client’s progress, only the achievement of a lasting developmental step. It is also not realistic to expect that all clients will reach the third step. But it is possible to use the framework to determine an optimal development for the client based on, for example, background, level of function or length of therapy. This way of using the framework can be seen as positive as it helps the art therapist to set realistic goals or, if necessary, assist the client in finding a more suitable contact, for example, counseling or support in everyday life.

Implications

Like other therapies, a prerequisite for art therapy is being able to capture, describe, and communicate the client’s change in a structured and clear manner. This observational framework offers one possibility. The framework aims to help art therapists to follow the client’s progress toward inner change in their practical work. It can be used as a reflective tool for assessing the efficacy of the treatment and while the outcome is mainly discussed with the client, it can also be communicated to e.g., relevant healthcare professionals (Haeyen & Noorthoorn, Citation2021). One of the difficulties involved in designing this qualitative observational framework was the need to formulate areas and sub-themes in a static way, which is very much in contrast to the dynamic, creative art therapy process. However, there was no indication that the art therapists who tested it experienced it as a problem.

Translating art therapy research in such a way that it can be used by practitioners is an important and delicate task. In our initial study, the art therapists described a quite similar perception of the clients’ change despite varying educational backgrounds (Holmqvist et al., Citation2017). The completed framework can therefore be considered to reproduce what this group of art therapists had seen, heard, observed, experienced, and reflected on during clients’ art therapy. The fact that the triangular relationship and the knowledge of psychodynamic theory seem to bind these art therapists together despite different art therapeutic training agrees well with earlier findings about art therapy and the triangular working alliance (De Witte et al., Citation2021).

Conclusion

We hope this observational framework will stimulate art therapists to identify and describe the patient’s progress from the outset, facilitate communication with the patient, and contribute to improved dialogue between patients, healthcare professionals, and researchers. We encourage art therapists to use it in their work. For further follow-up, we encourage experienced art therapists in health and social care to clinically test, research, and evaluate the observational framework’s clinical usefulness.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to all art therapists in Sweden who participated in the research by Holmqvist et al. (Citation2017) on which this observational framework is built. Without your experience and knowledge this work would not have been possible.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Gärd Holmqvist

Gärd Holmqvist, PhD, is art therapist and occupational therapist, Skaraborg Institute for Research and Development in Skövde, Sweden. Cristina Lundqvist-Persson is Associate Professor of Psychology, Department of Psychology, Lund University, Sweden, and Research Leader at Skaraborg Institute for Research and Development in Skövde, Sweden.

References

- Ainsworth, M. D. S., Blehar, M. C., Waters, E., & Wall, S. (1978). Patterns of attachment: A psychological study of the strange situation. Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Bat Or, M., & Zilcha-Mano, S. (2019). The art therapy working alliance inventory: The development of a measure. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1518989

- Betensky, M. G. (1995). What do you see?: Phenomenology of therapeutic art expression. Jessica Kingsley.

- Blomdahl, C., Guregård, S., Rusner, M., & Wijk, H. (2022). Recovery from depression—A 6-month follow-up of a randomized controlled study of manual-based phenomenological art therapy for persons with depression. Art Therapy, 39(1), 13–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2021.1922328

- Bowlby, J. (1988). A secure base: Clinical applications of attachment theory. Routledge.

- Braus, M., & Morton, B. (2020). Art therapy in the time of COVID-19. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S267–S268. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000746

- Case, C., & Dalley, T. (2014). The handbook of art therapy. Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group.

- Corem, S., Snir, S., & Regev, D. (2015). Patients’ attachment to therapists in art therapy simulation and their reactions to the experience of using art materials. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 45, 11–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.006

- Czamanski-Cohen, J., & Weihs, K. L. (2016). The bodymind model: A platform for studying the mechanisms of change induced by art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 51, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.08.006

- De Witte, M., Orkibi, H., Zarate, R., Karkou, V., Sajnani, N., Malhotra, B., Ho, R. T. H., Kaimal, G., Baker, F. A., & Koch, S. C. (2021). From therapeutic factors to mechanisms of change in the creative arts therapies: A scoping review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 678397. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.678397

- Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (1997). Attachment and reflective function: Their role in self-organization. Development and Psychopathology, 9(4), 679–700. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579497001399

- Guntrip, H. Y. (2018). Personality structure and human interaction: The developing synthesis of psychodynamic theory. Routledge.

- Haeyen, S., Chakhssi, F., & Van Hooren, S. (2020). Benefits of art therapy in people diagnosed with personality disorders: A quantitative survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 686. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00686

- Haeyen, S., & Hinz, L. (2020). The first 15 min in art therapy: Painting a picture from the past. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 71, 101718. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101718

- Haeyen, S., Kleijberg, M., & Hinz, L. (2018). Art therapy for patients with personality disorders cluster B/C: A thematic analysis of emotion regulation from patient and art therapist perspectives. International Journal of Art Therapy, 23(4), 156–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2017.1406966

- Haeyen, S., & Noorthoorn, E. (2021). Validity of the Self-Expression and Emotion Regulation in Art Therapy Scale (SERATS). PLOS One, 16(3), e0248315. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0248315

- Haeyen, S., van Hooren, S., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2015). Perceived effects of art therapy in the treatment of personality disorders, cluster B/C: A qualitative study. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 45, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2015.04.005

- Hinz, L. D. (2019). Expressive therapies continuum: A framework for using art in therapy. Routledge.

- Holmqvist, G., Roxberg, Å., Larsson, I., & Lundqvist-Persson, C. (2017). What art therapists consider to be patient’s inner change and how it may appear during art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 56, 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2017.07.005

- Isserow, J. (2008). Looking together: Joint attention in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 13(1), 34–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830802002894

- Isserow, J. (2013). Between water and words: Reflective self-awareness and symbol formation in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy, 18(3), 122–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2013.786107

- Kagin, S., & Lusebrink, V. (1978). The expressive therapies continuum. Art Psychotherapy, 5(4), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/0090-9092(78)90031-5

- Main, M., & Solomon, J. (1993). Procedures for identifying infants as disorganized/disoriented during the Ainsworth Strange Situation. In M. T. Greenberg, D. Cicchetti, & E. M. Cummings (Eds.), Attachment in the preschool years: Theory, research, and intervention (Vol. 1, pp. 121–160). University of Chicago Press.

- Monsen, J. T., Eilertsen, D. E., Melgård, T., & Ødegård, P. (1996). Affects and affect consciousness: Initial experiences with the assessment of affect integration. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 5(3), 238. https://doi.org/10.1037/t01210-000

- Nan, J., & Ho, R. (2014). Affect regulation and treatment for depression and anxiety through art: Theoretical ground and clinical issues. Annals of Depression and Anxiety, 1(2), Article no. 1008. https://hub.hku.hk/bitstream/10722/219307/1/content.pdf?accept=1

- Pénzes, I., Van Hooren, S., Dokter, D., Smeijsters, H., & Hutschemaekers, G. (2014). Material interaction in art therapy assessment. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 41(5), 484–492. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2014.08.003

- Rankanen, M. (2016). Clients’ experiences of the impacts of an experiential art therapy group. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 50, 101–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2016.06.002

- Rankanen, M. (2021). The embodied, intersubjective and aesthetic view into the process of therapeutic change. In V. Huet & L. Kapitan (Eds.), International advances in art therapy research and practice: The emerging picture (pp. 141–149). Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

- Schaverien, J. (2000). The triangular relationship and the aestetic countertransference in analytical art psychotherapy. In A. Gilroy & G. McNeilly (Eds.), The changing shape of art therapy (pp. 55–83). Jessica Kingsley Publisher.

- Shafir, T., Orkibi, H., Baker, F. A., Gussak, D., & Kaimal, G. (2020). The state of the art in creative arts therapies. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 68. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00068

- Shouse, E. (2005). Feeling, emotion, affect. M/C Journal, 8(6) https://doi.org/10.5204/mcj.2443

- Skaife, S. (2001). Making visible: Art therapy and Intersubjectivity. Inscape, 6(2), 40–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454830108414030

- Snir, S., Regev, D., & Shaashua, Y. H. (2017). Relationships between attachment avoidance and anxiety and responses to art materials. Art Therapy, 34(1), 20–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2016.1270139

- Springham, N., Findlay, D., Woods, A., & Harris, J. (2012). How can art therapy contribute to mentalization in borderline personality disorder? International Journal of Art Therapy, 17(3), 115–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2012.734835

- Stern, D. (2010). Forms of vitality: Exploring dynamic experience in psychology, the arts, psychotherapy, and development. Oxford University Press.

- Tomkins, S. (1984). Affect theory. In K. Scherer & P. Ekman (Eds.), Approaches to emotion. (pp. 163–197) Lawerence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Playing and reality. Penguin.