Abstract

Relational art therapy implemented in a women’s prison, as demonstrated by the Expressive Post program, illustrates a transformative method for overcoming psychological obstacles. Embedded in relational theory and response-based art making, this method emphasizes the establishment of a therapeutic milieu characterized by mutual empathy, creativity, and empowerment, all facilitated through collaborative artistic expression. A central feature of the program is the reciprocal exchange of art between therapist and participants, a process that fosters deep emotional connections and insights. Participants engaging in this program demonstrate enhanced abilities to articulate and process complex emotions, thereby promoting increased self-awareness and aiding in psychosocial rehabilitation. The perspectives outlined in this report may inspire a greater integration of the roles of therapist and artist.

This report describes the Expressive Post program, an egalitarian art therapy approach that can cultivate and sustain a progressive therapeutic milieu tailored to the unique needs and experiences of women in prison. We demonstrate the nuanced process through which I (the first author), immersed in the process of transformation, mirrored, and amplified the symbolic imagery elemental in client work. I sought guidance from a colleague (second author) who is an experienced supervisor in prison settings and skilled in utilizing art based intersubjectivity. Together we reflected on program processes, mapping the intricate therapeutic dynamics at play.

Prison imposes existential isolation, stemming from dehumanization and separation from families, exacerbating a loss of self (Covington, Citation2007). In response, inmates often adopt coping mechanisms like emotional suppression (Gussak, Citation2019). Art therapy in prisons offers a non-verbal outlet, promoting psychosocial wellbeing (Gussak, Citation2019). Group work has afforded positive dynamics and results, particularly for women in prison (Gussak, Citation2009). A relational art therapy approach where the therapist acts as a generous witness, and conduit between inside and outside worlds, is crucial in prison settings (Barak & Stebbins, Citation2017; Barlow et al., Citation2022).

The Expressive Post program, operational within a women’s prison, is deeply embedded in Haigh’s (Citation2013) principles of a Therapeutic Milieu. His framework underpins the program’s ethos, emphasizing attachment, containment, communication, involvement, and agency as critical mental health and personal development elements. This approach is particularly poignant in the context of a correctional environment, where prevalent experiences of abuse, neglect, and loss, as documented by Levenson and Willis (Citation2019), necessitate interventions that focus on restoring psychosocial well-being. The Expressive Post program thus emerges as a transformative initiative within the challenging milieu of a women’s prison, harnessing the power of response-based art making and exchange in therapy to catalyze personal growth, self-discovery, and positive change.

Relational Theory and Response-Based Art Making

The Expressive Post program, embedded within the milieu of women’s prisons, incorporates relational theory, as delineated initially by Miller (Citation2008) and subsequently applied to art therapy by Holmqvist et al. (Citation2019). Central to this theoretical framework is the emphasis on the creation of true connections, which are crucial for women’s psychosocial functioning. These connections, characterized by mutual empathy, creativity, and empowerment, facilitate the emergence of vitality affects—profound experiences imbued with energy and meaning that are born out of dynamic interpersonal interactions (Covington, Citation2007).

Expanding upon this foundation, the program adopts the relational art therapy approach proposed by Gerlitz et al. (Citation2020). This approach draws heavily on the philosophy of Buber (Citation1958), emphasizing the necessity of perceiving others as extensions of oneself, thereby harnessing creativity as a pivotal medium for achieving deep understanding and connection. This perspective promotes interactive dialogues between the therapist and participant and underscores the significance of mutual recognition and emotional resonance within the therapeutic relationship.

The Expressive Post program leverages response art making in art therapy. Comprehensively detailed by Fish (Citation2019) and further expanded by Nash and Zentner (Citation2023), this approach is seen as a critical tool for therapists to aid in self-reflection, sustaining both professional practice and development. Response art making, whether occurring before, during, or after clinical sessions or in the context of training and supervision, provides a means to nurture empathy and bring to light aspects of countertransference. Response art making involves therapists creating artworks that reflect their clients’ emotional states, thoughts, and experiences. Such work shared with clients can be instrumental in developing co-constructed narratives that may help establish or restore secure attachment patterns (Franklin, Citation2010).

Intersubjective Artistic Engagement

The program embraces principles articulated by Van Lith (Citation2014), emphasizing the intersubjective nature of the therapeutic process. Here, therapists immerse themselves in the art making process, often echoing their clients’ artistic styles or media preferences. Such immersion, informed by collaborative analysis of clients’ artworks, ensures that therapists engage in a respectful and attuned manner that initiates a unique expression of clients. This is an embodied approach that enables therapists to achieve a nuanced comprehension of their clients’ lived experiences.

Within the context of relational psychoanalytical art therapy, as characterized by Gerlitz et al. (Citation2020), there is an intricate journey of mutual response and learning between the client and therapist. The creation of intersubjective response artworks develops into co-constructed narratives, unfolding over time to form a unique visual language. This process demands complex empathetic and emotional attunement from the therapist and a commitment to a non-judgmental stance. As Franklin (Citation2010) highlighted, such a therapeutic process can enable clients to feel deeply seen, fostering self-empathy and compassion toward others.

The successful application of this relational approach hinges on the therapist’s ability to balance spontaneity, free expression, and the client’s best interests, responding intuitively and authentically (Franklin, Citation2010). Additionally, the therapist uses a certain level of self-disclosure and vulnerability, all within boundaries that respect the client’s state of confinement and unique circumstances (Hargaden, Citation2015). These are regarded as essential in creating true connections (Miller, Citation2008), that are mutually experienced and shared.

Program Implementation

Central to the program is the provision of art material kits, enabling participants to create postcard-sized artworks. These artworks may be inspired by five carefully chosen themes, curated to guide participants and enrich their therapeutic journey. The initial theme, Play, encourages self-discovery through material experimentation. Following this, the themes of Everyday life, Stories, and Dreams offer opportunities for deep personal reflection and the communication of meaningful narratives. Strategically positioned as the final theme, Open choice emphasizes personal agency, empowerment, and self-growth, particularly when participants have gained confidence in their artistic expression.

This program incorporates group studio workshops and individual art therapy sessions held weekly. These sessions play a crucial role in supporting participants as they move deeper into the meanings and processes articulated within their postcard artworks. The program’s composition facilitates diverse platforms for artistic expression and reflection, tailored to meet the participants’ varied needs and preferences.

A distinctive feature of the Expressive Post program is the reciprocal exchange of artwork between participants and the art therapist. This process involves collecting, creating, and weekly exchange of response art postcards. This exchange fosters a dynamic and empathetic dialogue, facilitating a deeper exploration of the themes and meanings inherent in the artworks. The art therapist actively engages with the participants’ postcards, culminating in the creation of corresponding artworks and mirrors, validates and extends the participants’ expressions, thereby enhancing the therapeutic relationship.

A significant aspect of the closure stage involves a group art exhibition and the production of a booklet within the prison setting. This exhibition, a collaborative effort curated by the participants, features a selection of artworks: a personal creation of the participant and a response artwork made by the art therapist. These pairs of artworks, digitally enlarged and printed for the exhibition, symbolize the shared journey and mutual respect fostered through the program. Importantly, all original artworks remain the property of the participants. In contrast, the response artworks created by the art therapist are presented as gifts, embodying the essence of the therapeutic alliance and shared experience.

Mapping the Process of Transformation

I piloted the Expressive Post program with over 85 participants across nine iterations. Each time the program ran for eight weeks, with volunteers who had responded to promotional posters and returned their expression of interest flyers to staff.

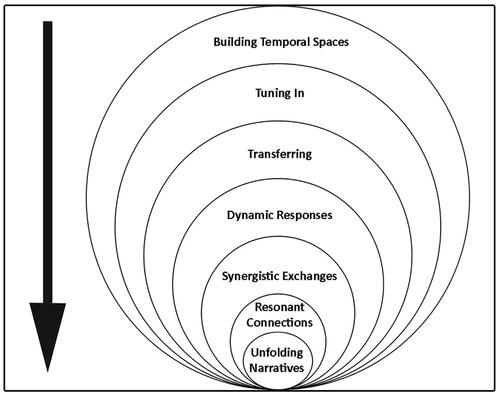

During comprehensive supervision sessions, marked by introspection and examination, a poignant analogy emerged. The nuanced dynamics inherent within the Expressive Post program were metaphorically likened to the gradual peeling back of seven layers of an onion (see ), emblematic of a complex therapeutic journey.

Figure 1 Tracing the Layers of Expressive Post

Building Temporal Spaces: This foundational layer of the Expressive Post program involves creating a safe and predictable environment within the unpredictable nature of prison life. Establishing a structured timeline and dedicated space for group art therapy along with the opportunity to make postcard art as exchange is essential in fostering a sense of stability, community, and privacy. These temporal spaces allow participants to begin feeling secure, reducing anxiety, and building trust in the therapeutic process. By adhering to a consistent schedule for workshops and postcard exchange participants can anticipate and prepare for each session, facilitating a dynamic interplay between the art therapist, the participants, and the creative process. This setting nurtures various relationships essential to the therapy:

Relationship with Self: Art making in this structured environment enables intrapersonal discourse, allowing participants to explore and understand their inner selves.

Relationship with the Group: The program cultivates nurturing relationships within the prison, providing a non-judgmental safer space where individuals can connect and support each other (Gussak, Citation2019).

Therapeutic Relationship with the Art Therapist: Participants engage with an independent, generous witness from outside the prison system, which offers a unique perspective and support in their therapeutic journey.

Enhancing Imaginal Spaces: Art therapy aims to restore the detached and replace the missing elements in participants’ lives. By bringing these aspects into conversation through art, the program creates rich, imaginal spaces for exploration and expression.

Holding Time: The artworks produced during the program document moments of prison life that might have otherwise felt wasted. Participants have described keeping their artworks and the responses made by the art therapist in sequence to make sense of or give meaning to their time in prison. The artworks chart the experience of a particular time and place but may also contain the “potential for communication across time and space” (Wynter‐Vincent, Citation2022, p. 661).

Tuning In: Once the foundational layer is established, the focus shifts to ‘Tuning In,’ a phase characterized by deep listening and attunement to the participants’ needs and expressions. The art therapist engages in active listening and empathetic understanding, responding sensitively to the nuances of each participant’s artistic expression. This could involve acknowledging the emotional content in a drawing or encouraging further exploration of a theme that a participant seems drawn to. The aim is to create a supportive atmosphere where participants feel seen and heard, facilitating authentic self-expression.

Transferring: In this layer, participants move from being passive subjects to actively externalizing and objectifying their experiences through art. This is a critical shift where emotional experiences are transformed into tangible artworks. For instance, a participant might channel feelings of frustration into a clay sculpture, symbolizing and externalizing their inner world. Engaging in art making allows participants to gain insights into their narratives and begin the process of self-reflection and understanding.

Dynamic Responses: In this layer of the Expressive Post program, the art therapist becomes significantly more interactive, extending their insights beyond mere interpretation of the participants’ artworks. This requires a deep level of emotional and imaginative engagement from the therapist. They provide a countertransference response through an image that reflect their understanding and perspective of the participant’s emotional state.

During this phase, the therapist takes time from home each week to intimately engage with each postcard artwork created by the participants. This involves thoughtful consideration of the art qualities, such as the marks made, the colors, and the textures used, as well as reflecting on the conversations had with participants, their shared life experiences, and other artworks they created during the previous workshops. In crafting response art pieces, the therapist sometimes adopts the participant’s style and prioritizes different aspects, by tuning in to their own emotional and physical connections to the artwork.

Synergistic Exchanges: This layer of the Expressive Post program is characterized by the emergence of synergistic responses, where the art therapist and participants collaborate in exchanging a more intricate shared visual language. Meaning and understanding is developed through the previous layers, over the course of the program, using the exchanged art pieces as a foundation for further elaboration and insight.

By this stage of collaboration, thoughtful conversations have occurred within the therapy sessions, expanding, collaborative and deepening the meanings derived from the postcard artworks. These discussions facilitate a mutual exploration of the artworks, allowing the therapist and participants to contribute to and enrich the evolving narrative. The result is a dynamic and interactive process where the collective input leads to a richer, more nuanced understanding of the expressed themes and experiences.

Resonant Connections: This layer highlights the transformative potential of response art exchange in therapy. Here, the intersubjective process facilitates the reconciliation of complex emotions such as grief, loss, shame, and guilt. Art becomes a medium through which participants can confront and process these deep-seated feelings, leading to emotional healing. For instance, a painting might evoke a strong emotional response, indicating a resonant connection between the participant’s inner experience and the intersubjective image.

Unfolding Narratives: The core of the process, Unfolding Narratives, involves participants delving deeper into their artistic journey, uncovering, and articulating their personal stories through their postcard creations and curating the final exhibition. This layer is marked by the emergence of themes, symbols, and metaphors that have personal significance to the participants. Creating and reflecting on these artworks helps participants to weave together the various threads of their experiences, forming a coherent narrative that provides insight into their inner worlds.

Case Example

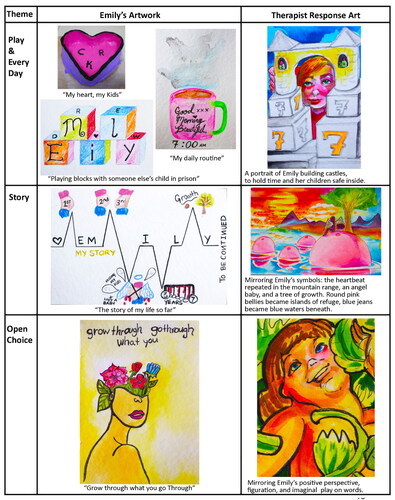

The following narrative focuses on the intricate relational dynamics between me, the art therapist, and ‘Emily’ (a pseudonym), who participated in the Expressive Post program. Accompanied by a table of images (see ), this vignette provides a visual narrative of the evolving art and postcard exchanges, capturing the therapeutic journey. For confidentiality, some of Emily’s original artworks were replicated by the first author, with her consent secured for publication.

Figure 2 Visual Narrative Between Client and Art Therapist

Building Temporal Spaces and Tuning In

The group art therapy workshops were consistently held on the same morning each week, a routine which incorporated clear verbal and written direction. Emily embraced all the ‘temporal spaces’ provide by the program. On one occasion, having conflicting appointments, Emily asked for another participant to collect the new week’s theme letter. The group workshops, embraced diverse artistic methods such as drawing, painting, sculpture, and printmaking. They offered structure, predictability, and playful respite and were a stark contrast to the often chaotic prison environment. Emily told me in the first workshop how she had kept on her wall, a drawing made by me in a previous art therapy program. This image, that made its way back into our therapeutic relationship, was originally drawn in response to a conversation we had around how much Emily missed her children.

Transferring and Dynamic Responses

Beginning with the theme ‘Play,’ Emily in the workshop externalized her emotions and experiences into a painted clay form. Emily’s heart-shaped bowl symbolized her bond with her children. Although unable to attend the second workshop, Emily displayed enthusiasm and commitment to the program by making multiple postcard artworks in her own time. Entrusting me with these creations in the subsequent workshop, Emily enabled our planned collaboration. My first responsive engagement involved creating a composite artwork that interwove elements of Emily’s sculptural and pictorial compositions. This integrated creation aimed to enhance the therapeutic connection and foster mutual understanding between us. The subsequent theme ‘Story,’ workshopped in the group, was marked by personal insights and shared narratives. Emily transitioned this experience into her personal artmaking, making a postcard to show her own ‘Story’ depicted as a heartbeat monitor, timeline of her life, interspersed with recurring motifs. This image and the contents it conveyed moved me deeply and instilled a sense of urgency and responsibility. I felt my response needed to bear witness to the depths of loss expressed in Emily’s artwork but should also celebrate her strengths.

Synergistic Responses and Resonant Connections

My artwork in response to Emily’s graphic story exemplified the synergy in our relationship. My piece, mirrored, reconstructed, and amplified Emily’s motifs and colors. Her heart monitor line reappeared in my mountain range; her pink pregnant bellies became islands thrust up from blue waters. The image represented a rich tapestry of our shared experiences and emotions. Emily’s positive response to this artwork, revealed while I sat beside her, spoke to the connection fostered through collaborative art making, highlighting art therapy’s capacity to nurture empathetic connections and emotional healing.

Unfolding Narratives

Emily’s evolving narrative through her ‘Open’ themed postcard, signified personal growth amidst adversity. I celebrated her positive outlook in my response art. The group exhibition at the program’s end involved participants choosing a personal artwork and a corresponding response art piece created by me. Emily’s selection of the ‘Story’ themed artwork and accompanying statement echoed a transition from personal experience to a collective voice, evidencing the journey’s therapeutic impact. Her statement read: “My Story; My life. I chose this artwork to be displayed because it was the most meaningful one that I did. I’m sure a lot of other women could relate in some way or another. And the response Hayley did is so important to me with my Angel baby.”

Emily later shared with me that she had displayed the entire series of postcards to her mother during a video call, indicating the value and personal significance of these artworks in her life. She revealed how the program aided her in processing the grief of a significant loss, a process she could not engage in amidst the turmoil of her arrest and subsequent incarceration.

Conclusion

The Expressive Post program elucidates the significant role of relational theory in shaping an art therapy approach in correctional settings. The relational framework has the central tenet of establishing an authentic connection between the therapist and the client, fostered through shared artistic creation and empathetic exchange. In this environment, the non-verbal communication inherent in artistic expression becomes a powerful tool for transcending barriers of traditional dialogue, allowing for a deeper exploration of personal experiences and emotions (Gussak, Citation2019).

The relational approach in art therapy, as demonstrated in this program, encourages therapists to guide and actively participate in the art making process. This method breaks down the traditional roles of therapist and client, fostering a more egalitarian and collaborative relationship (Van Lith, Citation2014). Such dynamics are pivotal in correctional settings to form true connections (Miller, Citation2008) in places, within systems of power imbalance and institutional hierarchies, that can exacerbate trauma, feelings of disempowerment, and isolation (Covington, Citation2007; Farmer, Citation2019; Levenson & Willis, Citation2019). We hope that this brief report may inspire practitioners to further harness their own artistic and visual communication skills, to offer an equitable, compassionate, and inclusive approach to working in prison settings.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Barak, A., & Stebbins, A. (2017). Imaginary dialogues: Witnessing in prison-based creative arts therapies. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 56, 53–60.

- Barlow, C., Soape, E., Gussak, D. E., & Schubarth, A. (2022). Mitigating over-isolation: Art therapy in prisons program during COVID-19. Art Therapy, 39(2), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2021.2003679

- Buber, M. (1958). I and Thou, 2nd ed. Charles Scribner’s Sons.

- Covington, S. (2007). The relational theory of women’s psychological development: implications for the criminal justice system. In R. Zaplin (Ed.) Female offenders: Critical perspectives and effective interventions (2nd ed., pp. 1–25). Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- Farmer, M. (2019). The importance of strengthening female offenders’ family and other relationships to prevent reoffending and reduce intergenerational crime (pp. 176–191). Ministry of Justice.

- Fish, B. J. (2019). Response art in art therapy: Historical and contemporary overview. Art Therapy, 36(3), 122–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2019.1648915

- Franklin, M. (2010). Affect regulation, mirror neurons, and the third hand: Formulating mindful empathic art interventions. Art Therapy, 27(4), 160–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2010.10129385

- Gerlitz, Y., Regev, D., & Snir, S. (2020). A relational approach to art therapy. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 68, 101644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2020.101644

- Gussak, D. (2009). The effects of art therapy on male and female inmates: Advancing the research base. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 36(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2008.10.002

- Gussak, D. (2019). Art and art therapy with the imprisoned: Re-creating identity. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429286940

- Haigh, R. (2013). The quintessence of a therapeutic environment. Therapeutic Communities, 34(1), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1108/09641861311330464

- Hargaden, H. (2015). An analysis of the use of the therapist’s ‘vulnerable self’ and the significance of the cross-fertilization of humanistic and Jungian theory in the development of the relational approach. Self & Society, 43(3), 208–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/03060497.2015.1092323

- Holmqvist, G., Roxberg, Å., Larsson, I., & Lundqvist-Persson, C. (2019). Expressions of vitality affects and basic affects during art therapy and their meaning for inner change. International Journal of Art Therapy, 24(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/17454832.2018.1480639

- Levenson, J. S., & Willis, G. M. (2019). Implementing trauma-informed care in correctional treatment and supervision. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 28(4), 481–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/10926771.2018.1531959

- Miller, J. B. (2008). How change happens: Controlling images, mutuality, and power. Women & Therapy, 31(2-4), 109–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703140802146233

- Nash, G., & Zentner, M. (2023). Working alongside: Communicating visual empathy within collaborative art therapy. Journal of Applied Arts & Health, 14(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/10.1386/jaah_00129_1

- Van Lith, T. (2014). A meeting with ‘I-Thou’: Exploring the intersection between mental health recovery and art making through a co-operative inquiry. Action Research, 12(3), 254–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476750314529599

- Wynter‐Vincent, N. (2022). In C: Towards a ‘Bionian’ theory of creativity. British Journal of Psychotherapy, 38(4), 655–665. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjp.12769