Abstract

Families are the most significant communication partners for an individual with complex communication needs. Even though family-centered approaches are recommended to support augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) services for an individual, it is difficult to establish a successful plan that fits each individual’s family. A framework for practitioners is proposed to effectively obtain and understand information about a family’s unique dynamics as part of service delivery to positively impact AAC device uptake and long-term use. The goal of using this model is to minimize the disruption to the family while maximizing the integration of the AAC system. This paper proposes and illustrates a framework to enrich AAC services through the integration of several theoretical models of family systems theory, family paradigms, and a procedure called the self-created genogram. This paper begins by reviewing ecological family systems theory and family systems to guide and provide a framework to support effective AAC implementation. The process of self-creating genograms is then introduced as a means to obtain a rich perspective on family characteristics and dynamics that is informed by the individual who uses AAC. All of this information allows professionals to provide relevant information and tailor options for the family. As a result, the family is able to make informed decisions about AAC intervention in a manner most consistent with how they typically operate. Finally, we apply this framework to a hypothetical case of a child with autism and complex communication needs across three timepoints (preschool, late elementary/early middle school, and high school/post-secondary transition) to demonstrate how this framework can be used in clinical practice.

This paper introduces a framework to enrich augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) services through the integration of family systems theory, family paradigms, and self-created genograms. Literature from each of these areas is synthesized to offer suggestions for optimizing clinicians’ effectiveness in working within individual family structures and preferences (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; Connolly, Citation2005; Hidecker, Jones, Imig, & Villarruel, Citation2009).

The proposed framework is consistent with current clinical approaches of interprofessional practice in that it involves an integrated framework that equips members of an AAC team to solicit information about a family’s unique dynamics. The goal is to offer a means to maximize the input of the individual who uses AAC as well as their family, in order to center the services directly within the individual and their family and, in turn, positively impact AAC device uptake and long-term use. Depending on the needs of the individual who requires AAC and the dynamics of the AAC team, educators (e.g., special or general teachers), support staff (e.g., paraprofessionals), or therapists (e.g., speech-language pathologists [SLPs], behavior analysts, occupational therapists) may administer the proposed genogram activity. For this reason, the words “practitioner” and “AAC team” are used. The proposed framework is illustrated through the hypothetical case of a child, “Tommy”, and his fictional family, across three timepoints: preschool, middle school, and high school transition. Tommy has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and also has complex communication needs; his profile is a composite of that of several individuals.

Models of family functioning and interventions

Family-centered practices

Family provides a rich context within which children build language skills. Consequently, services for children must not occur in isolation (Minuchin, Citation1985); otherwise, practitioners risk establishing change outside the family context that does not carry over to the family context (see Crawford, Citation2020). For example, a school practitioner might teach a child to request a break from work by exchanging a photograph or graphic symbol. At home, the same child may resort to striking others when frustrated or overwhelmed if the family and practitioner have not collaborated to develop a plan to incorporate picture exchange into the family’s routine.

Previous research has identified four models for considering the family unit throughout childhood and adolescence (Dunst, Citation2002; Dunst, Johanson, Trivette, & Hamby, Citation1991): (a) Professional-centered, in which the professional is viewed as the expert and determines the family needs; (b) Family-allied, in which families are considered the agents who carry out the intervention deemed appropriate by the professional; (c) Family-focused, in which families and professionals collaboratively define what families need, but families are viewed as needing professionals’ guidance; and (d) Family-centered, in which professionals are viewed as resources for families and interventions maximize family decision-making. The literature emphasizes the importance of collaborating with families throughout the decision-making process related to AAC (Baxter et al., Citation2012). The key to family-centered service is to involve the family in deciding what practices and interventions to adopt (Crais, Roy, & Free, Citation2006).

There is a need to empower families and provide supportive environments to develop the most appropriate AAC services (Mandak & Light, Citation2018a). Despite increased attention to family-centered services, a gap exists between recommended practices and actual practice in the field. AAC professionals are generally aware of the importance and benefits of involving families in AAC decision-making and services but may have limited experience with regard to their own family-centered implementation (Mandak & Light, Citation2018b). Furthermore, practitioners may believe they are providing family-centered services when they are actually providing professional-centered practices (Mandak & Light, Citation2018a). Mandak, O'Neill, Light, and Fosco (Citation2017) applied family systems theory to clients who required AAC. They argued that basing services in family systems theory might promote a strong professional-family partnership, leading to goals and interventions that encompass the true needs and desires of the individual across the lifespan.

Ecological systems theory

When considering families and family systems, another important theoretical framework is Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979). This theory, like family systems theory, argues that in development and in clinical service provision it is necessary to consider the functioning of a child within the settings in which the child operates, as well as in relation to other contexts that can impact the child even though the child does not interact with them directly (see Crawford, Citation2020, for a review). At least four nested systems exist within ecological systems theory: the microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem. The microsystem represents the settings in which the individual interacts directly and regularly; examples of microsystems can be family, school settings, or sports activities. The mesosystem reflects the relationships between two or more microsystems; this system is itself made up of microsystems and, specifically, their interactions. Examples of mesosystems might be the parent-professional communication (for home and school microsystems) or parent-coach relations (for home and sports microsystems). The exosystem involves settings that may impact some part of the child’s life, but that the child does not directly interact with themselves. The functional impact of an exosystem occurs indirectly through its influence on a member of one of the child’s microsystems. For example, the workplace schedules of a child's parents will impact the child’s routine; the sports schedule of a sibling may affect the amount of time a parent is available to help a child with homework. Finally, the macrosystem consists of cultural values, customs, and laws that affect the inner systems. An example would be the educational and/or healthcare system available to a family, which could dictate availability of AAC services or access to an AAC system via insurance. Furthermore, if families are required to spend extensive time dealing with health insurance issues, there will be less time or energy to invest in incorporating the AAC system into their daily lives.

Introduction of AAC to an individual can disrupt the regular balance of the family system and impact individual micro- and mesosystems. Consequently, successful implementation depends on all members within the family system adapting to the change. For instance, if a family typically uses manual signs, but the practitioner introduces an AAC device, the family might feel uncomfortable and inconvenienced by using the device. Unlike manual signs, which are always available to the individual, a device is external to the user’s body and therefore has to be made available and can be forgotten or lost. Furthermore, the introduction of an AAC device requires time for the family to learn. Additional family resources of time, space, commitment, and materials need to be allocated to introduce and maintain the device (e.g., learning how to use the device, charging the battery, making sure the device is available, and programming vocabulary).

Family characteristics and dynamics

It is impossible to understand the various ecological systems that apply to a family without also understanding that family’s characteristics and general dynamics. Although formal approaches are available to determine specific family paradigms (e.g., Hidecker et al., Citation2009), there is a need to obtain a more general description of family characteristics. The ways in which a family makes decisions about their individual and collective goals and their use of time and resources can inform successful AAC implementation. For example, some families value including multiple members in decision-making while others rely on one particular member. Some families are very structured in their routines and prioritize certain activities while others are fluid with their time and shift priorities based on needs of various members on any given day. Furthermore, individuals within one family may view their family characteristics differently (e.g., one sibling may view their mother as the decision-maker while another sibling views the father as the decision-maker). Another important consideration is how family members interact with each other. Many times, professionals only see one family member and do not observe the interactions between family members. This might be due to family preferences about who should interact with the clinician, or external factors such as limitations on what clinicians can bill to medical insurance. The potential influence of billing as a limiting factor on the clinician’s ability to meet the whole family is an example of how the macrosystem interacts with the communicator’s mesosystems and microsystems. In either case, the professional has limited information about these interactions and the roles each member plays in day-to-day family functioning.

Knowing who drives decision-making, how family members each respond to new ideas, and whether there is any resistance to change is beneficial when planning to introduce an AAC system. Recognizing family roles should serve as an avenue to develop solutions and present AAC options that best complement the family’s style and interactions. For instance, some interventions and systems promote predictable interactions that can be carried out at specific times. This structure may be ideal for a routine-oriented family, but would be much more difficult for a family whose schedule is less structured; the latter may have more success with a system that allows for quick and spontaneous programming and an emphasis on multi-modal communication (e.g., a greater emphasis on non-verbal and/or family-unique forms of communication).

Self-created genograms

In this paper, it is argued that the use of self-created genograms can be an important means to solicit information about a family’s ecological systems, characteristics, and dynamics. This tool can not only be used to open conversations about a family’s unique micro- through macrosystems but also to promote discussions of the family characteristics and dynamics. Perhaps more importantly, self-created genograms provide natural opportunities for participation by individuals with limited expressive speech because they can be created using a variety of modes and materials.

The term genogram is often used to describe drawings, including drawings created by individuals with disabilities. Genograms are a well-established and effective method of collecting data about diverse within- and outside-of-family relationships (Connolly, Citation2005; Leibowitz, Citation2013). This approach has been used to evaluate relationships of individuals with intellectual disabilities and their parents (Lev-Wiesel & Zeevi, Citation2007) as well as their siblings (Zaidman-Zait, Yechezkiely, & Regev, Citation2020). Genograms can be used to discuss resources in a family, life stages, significant timepoints, and people who share a home regardless of their relationships (Turabian, Citation2017). These discussions can provide a better understanding of a family’s behavior and beliefs. Detailed information about the process of constructing a genogram, including procedures and suggested topics and questions, can be found in tutorials by Connolly (Citation2005) and Milewski-Hertlein (Citation2001).

In a systematic review of the use of genograms in nursing, Piasecka, Slusarska, and Drop (Citation2018) discussed the history of the genogram and its expanded use in social work, psychology, and education. Historically, genograms were developed using a formal process and specific symbols to represent relationships and structure across three generations. As their use expanded, unique symbols identified meaningful information beyond familial relationships such as diabetes in a family member. With children, photographs, drawings, or even objects (e.g., rocks, pinecones, toys) can be used instead of symbols to represent the family.

In the family counseling literature, Connolly (Citation2005) recommended the use of the self-created genogram. In this strategy, clients construct pictorial representations of their families with guidance from the practitioner. Allowing each individual to create a genogram based on who they consider family is one means by which practitioners can respect the diversity of families within and across cultures and identify people who are important to the client. This information is then analyzed to chart the basic family structures, record information about individual family members, and delineate family relationships (Connolly, Citation2005). Placed in the context of ecological systems theory, these activities can help solicit information about the various micro-, meso-, and exosystems related to the target client. By developing an understanding of the family characteristics and dynamics, practitioners can consider the probable role of each individual in an AAC intervention, thus adhering to family-centered AAC practices. The use of a self-created genogram with clients who use AAC could be a beneficial way to distinguish the roles of different family members by asking the creator to describe the genogram.

This approach also aligns well with the concept of Social Networks (Blackstone & Hunt Berg, Citation2003). Developing a self-created genogram has the potential to highlight the key role of communication partners in interactions while also helping to maximize the involvement of the person who communicates with AAC in identifying who is currently in their social networks. The self-created genogram can extend the notion of social networks by identifying relational dynamics between individuals and their environments as well as how they change over time. During early childhood, family members and caregivers would be considered as communication partners. When individuals move through elementary and secondary school into college, the communication partners would be classmates, teachers, and others in the community; in adulthood, the partners would be people from the workplace and recreational groups. At all stages, the person who uses AAC can be involved in generating the genogram via whatever modalities are available to them (e.g., pointing to photographs, drawing, orthography). For creators who have difficulty communicating due to age or disability, other family members may provide valuable support and information. The process of generating the genogram can elicit important information about potential communication partners, supporters, meaningful topics, and vocabulary while emphasizing the value of the self-defined family. This approach allows for richer, family-led discussion that can help identify the unique influences and barriers to successful AAC implementation.

In summary, family-centered AAC services are critical to ensuring that functional communication skills are carried over into the context of the family – a rich context for the development of language skills. Family-centered AAC services aim to maximize family decision-making, create a sense of empowerment for family members of the individual with complex communication needs, and minimize disruptions to a family’s routine. Centering the family in their own system through the self-created genogram will allow the clinician to better understand family characteristics and dynamics, recognize family member roles, and identify availability of resources (e.g., time, materials) that might impact AAC learning. The literature suggests a gap between recommended practices and actual practices related to provision of family-centered services (Mandak & Light, Citation2018a). The use of self-created genograms offers a means to begin to close this gap by providing rich information about family structures and dynamics.

Application to a case composite of a child who uses AAC

This section describes the hypothetical case example of Tommy and his family, who are composites drawn from individuals the authors have met in their roles as clinicians, educators, and family members. The case example represents a family dynamic that AAC practitioners may encounter, and shows how the proposed framework can enhance AAC practices for individuals with complex communication needs and their families by promoting communication opportunities across communication partners and within meaningful contexts. Of course, each genogram will be unique to each individual and family, so the questions and strategies used by clinicians will be most effective when they are individualized to each client and family.

Timepoint 1: Preschool (age 2;6) (years;months)

Tommy was diagnosed with ASD at 2 years of age through his early intervention program. At the time of diagnosis, he had no functional speech and used gestures, facial expressions, and some vocalizations to communicate. His mother reported that she anticipated most of his needs. Tommy occasionally retrieved items by himself, even climbing closet shelves to do so. When Tommy was already engaged in a communicative exchange with someone and asked directly about what he wanted, he pointed to desired objects. His sibling, Sam, who was 2 years older, was reportedly an interpreter for Tommy in many contexts.

Tommy demonstrated some challenging behavior when he was upset or tired (e.g., whining, crying), but the magnitude and duration of these were not reported to be greater than expected for a typically developing toddler. Tommy was generally content and occupied himself for hours with his toy cars and trucks. He also played cooperatively with his older sibling. Sam usually directed imaginative play, and Tommy enthusiastically followed.

Tommy’s parents were married, and all four family members lived in the home. When the children were young, their mother cared for them in the home while their father worked full-time. This provided frequent opportunities for outings to the library and neighborhood parks. Extended family included two sets of grandparents and numerous aunts, uncles, and cousins. Tommy and his immediate family visited their extended family about once a year.

Tommy participated in a multidisciplinary evaluation as part of planning for the transition from early intervention to preschool services. His mother accompanied him to the evaluation. The assessment team applied the framework for centering the family in their support system before making any recommendations for technology or interventions. The practitioners used a self-created genogram to obtain information about family dynamics. During the evaluation, one of the practitioners also integrated the self-created genogram and the family characteristics into the ecological systems framework.

Creating the genogram

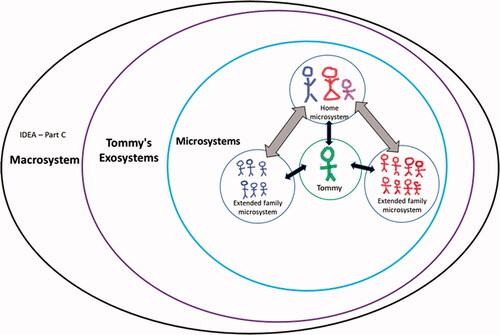

presents the self-created genogram related to Tommy that was generated during Timepoint 1, illustrating three microsystems and the mesosystems to which they are related. Tommy created his portion of the genogram with assistance from his parents. Although it is important for an individual who uses AAC to have as much independence as possible in creating a genogram, for a child as young as Tommy, input from parents or other informants is typically necessary. Markers and crayons that Tommy could use with assistance from his parent were supplemented with pictures cut out of children’s magazines and printed from the Internet, from which Tommy could choose. The content for the printed pictures were supplied by Tommy’s mother prior to the meeting, and printed out by the clinician. These allowed Tommy to select items that were too difficult for him to draw using crayons.

Figure 1. Tommy’s Systems at Timepoint 1 (Preschool) based on self-created Genogram. Note. IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Arrows represent interactions. Solid black arrows indicate Tommy’s relationships with his microsystems, and gray arrows indicate mesosystem relationships.

Micro- and mesosystems

Tommy’s mother provided most of the information for the genogram during the semi-structured interview, asking Tommy for confirmation via head nods and shakes using questions such as, Grandma is part of our family. We should draw Grandma in too, shouldn’t we? Tommy drew a simple stick figure with intermittent hand-over-hand assistance. His mother’s use of leading questions (e.g., the suggestion that We should draw Grandma in too) led the clinician to introduce strategies like asking open-ended questions, such as Who else might we add? and to suggest providing Tommy with photographs of some of the other possible family members that could be included for him to select from. Open-ended “wh” questions is an effective strategy used to prompt higher content turns and assist with semantic and syntactic development for individuals who use AAC (Binger, Berens, Kent-Walsh, & Taylor, Citation2008). These open-ended questions also help to elicit a more diversified set of answers with a wider range of vocabulary (Reja, Manfreda, Hlebec, & Vehovar, Citation2003). In addition, it was thought that asking open-ended questions would allow Tommy to generate a more autonomous response rather than responding with “yes” or “no” to an idea generated by his mother. The practitioner asked a series of questions based on the picture, in order to elicit more information about the family dynamics. To answer the question, Who lives with you? Tommy’s mother pointed to each stick-figure person within the house and named them while Tommy nodded in response. The four figures represented the parents, Sam, and Tommy. When asked, Who are these people outside? Tommy’s mother explained that these particular figures represented maternal and paternal grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins. She identified several relatives by name.

Identifying the family characteristics and dynamics

The practitioner asked Tommy’s mother open-ended questions about the self-created genogram in order to obtain information about how the family used their resources to achieve their goals (Deutsch & Hidecker, Citation2015; Hidecker et al., Citation2009). Some examples of questions were:(a) What does a typical weekday look like for your family? (b) Where does Tommy like to spend time at home? and (c) What are some of your goals for Tommy’s communication?

This semi-structured interview revealed that Tommy’s mother generally ran the household. She maintained groceries and other supplies, prepared most meals, organized the family’s schedule, and was the primary childcare provider. The father was likely to agree with the mother’s decisions, or at least to move with the general family flow. Sam often presented alternatives or challenges to the mother’s decisions. Tommy himself generally exerted little power in changing the actions or decisions of the family.

In addition to these family dynamics, the interview revealed routines. Sam attended a part-day preschool program. Tommy and Sam played together every day after Sam came home from school. The whole family ate dinner together nightly and discussed the events of the day. After dinner, they generally watched television together, and then the children got ready for bed. On weekends, both parents shared childcare and other household responsibilities.

Implications of the genogram for Tommy’s AAC

The interview revealed that improving Tommy’s communication was a meaningful goal for the family and that they were willing to invest resources (e.g., time, energy, materials) into this goal. AAC implementation may be more adoptable, particularly by highly structured families who prefer predictable routines, when the AAC systems require little change to their daily routines (Hidecker et al., Citation2009). Integrating the AAC system into currently practiced routines identified by Tommy’s mother could effectively improve Tommy’s communication within the family microsystem.

A family’s material resources may be related to their access to and their use of technology (Hidecker et al., Citation2009). Tommy’s family had technology in the home, increasing the likelihood of uptake for speech-output technologies such as a speech generating device or tablet-based system. Speech output technologies have been found effective for individuals with ASD (for a review see Schlosser & Koul, Citation2015). Moreover, highly structured families like Tommy’s might prefer an AAC device with speech output to lower-tech options without speech output, because the sound is closer to traditional speech (Hidecker et al., Citation2009). The practitioner determined that integrating a tablet-based AAC app with photographs of meaningful events to use as visual scene displays (VSDs) would support Tommy’s communication in existing family routines. VSDs contextualize symbols within proportional images (Light, McNaughton, & Jakobs, Citation2014) and have been shown to promote communication for beginning communicators and children with ASD (e.g., see Light, McNaughton, & Caron, Citation2019 for review).

As this family was committed to improving Tommy’s communication, Tommy’s mother and Sam met with the practitioner to become familiar with the AAC device and learn intervention strategies. Tommy’s mother chose to introduce the AAC device into two of the family’s daily routines: breakfast and playtime with Sam. Sam aided the practitioner in selecting relevant vocabulary targets and learned how to quickly add vocabulary to the VSD.

At first, Tommy refused to use the device. This was likely due to the disruption of his routine of having his needs anticipated. For example, breakfast provided a predictable and meaningful context. Each morning, Tommy’s mother gave him a plate of French-toast sticks. The first few mornings that Tommy was presented with the AAC device rather than his expected plate of French toast sticks, he dropped to the floor and started screaming. In order to promote Tommy’s use of the AAC device, the practitioner collaborated with Tommy’s family to determine strategies (e.g., modeling, immediate reinforcement) to integrate the AAC system into his breakfast routine. After a few days in which Tommy’s parents modeled its use during breakfast, and provided verbal and tangible feedback when he began to use it himself (for instance, offering him the maple syrup when he touched that symbol, with or without assistance), Tommy began to use the device reliably. Once the breakfast routine was in place, the practitioner and Tommy’s parents identified other routines in the day to begin to integrate the AAC throughout Tommy’s activities.

Timepoint 2: Late elementary/early middle school (age 12)

The second timepoint occurred in late elementary school. Tommy was receiving special education services. Tommy’s academic progress in the intervening 10 years had included substantial language and literacy gains. At this time, Tommy’s AAC device was a mobile tablet with an app that mostly contained grid-based topic displays. He consistently used this AAC device to make requests and answer direct questions. Tommy recognized approximately 100 sight words, and he was beginning to grasp letter-sound correspondences. On one occasion, Tommy had used a keyboard to experiment with invented spelling, producing m-l-k repeatedly and then retrieving milk from the refrigerator.

Creating the genogram

Micro- and mesosystems

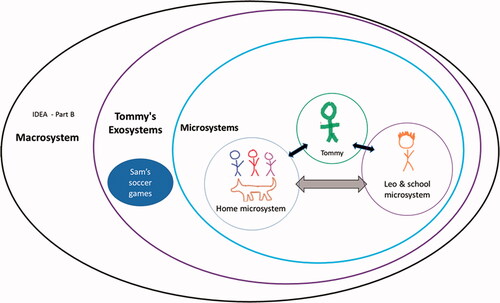

The team met with Tommy and his mother, and this time, Tommy created the genogram mostly by himself, primarily through drawing with colored pencils and selecting from among photographs of family and friends provided by his mother beforehand. He received support in the form of open-ended questions from the practitioner with very little input from his mother. Tommy provided telegraphic responses to questions using his AAC device. For example, when asked, What does Dad do? Tommy answered, “Go work”. As illustrates, some changes had taken place between Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 2. First, Tommy’s family had gotten a dog. Each family member had developed a unique relationship with this pet. Tommy was involved in feeding the dog daily, and the dog often laid next to him on the floor while the family watched television in the evening; thus, the dog was now placed as part of the family microsystem.

Figure 2. Tommy’s Systems at Timepoint 2 (elementary/early middle school) based on self-created Genogram. Note. IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Arrows represent interactions. Solid black arrows indicate Tommy’s relationships with his microsystems, and gray arrows indicate mesosystem relationships.

The practitioner also asked, Who do you spend time with at school? in order to gain information about potential communication partners outside the home setting. The answer introduced Leo, a friend he had made during elementary school. Leo had shared a classroom with Tommy from kindergarten until fourth grade. Despite being moved into different classrooms, Leo and Tommy continued to play together at recess, often occupying adjacent swings for as much of the play period as they could. Teachers reported that although the two shared very little verbal communication, they just seemed to “get” each other. After establishing that Leo should be represented in Tommy’s genogram, the practitioner encouraged Tommy to draw a picture of Leo that could be glued to the genogram during the discussion with his mother. This created a second, new microsystem that included Leo as part of the school microsystem.

At this timepoint, Tommy, his family, and their support team were preparing for his transition from elementary to middle school. Changing schools involved a new school building in a different location, a larger student population, a different set of peers, having to change classes instead of staying in one classroom, and an increase in academic demands. This placed additional demands with regard to communication between the family and the school and arranging social get-togethers with Leo. These considerations related to the family/school mesosystem and who was responsible for the communications. The family and team agreed that Tommy would benefit from AAC supports to manage these transitions and that they would provide him with some experience in beginning to manage family/school communications.

Exosystem

Another change between Timepoint 1 and Timepoint 2 was that Sam had joined the local soccer team, which had practices twice per week in addition to weekend games. Tommy did not directly participate in the soccer games or the socialization that took place on the sidelines, in part because of challenges with integrating AAC use into this context. In addition the bright, noisy environment at the soccer field sometimes overwhelmed Tommy, and he tended to stay close to his mother or sit in the car with the door open. On several occasions, during the shuffle of getting multiple people and a dog into a vehicle along with Sam’s soccer equipment, Tommy’s AAC device was accidentally left on the kitchen table. Finally, Sam expressed frustration with the emphasis on Tommy during an activity that was special for Sam. Sam was angry that making the soccer games a therapeutic context for Tommy drew more attention to their family’s “weirdness.”

Because these soccer games affected the time his mother was able to spend with Tommy and Sam’s feelings about their sibling, the soccer games were currently serving as an exosystem that negatively affected Tommy. Yet, the practitioner noted that Sam’s soccer games could serve as a predictable routine where Tommy could safely practice communicating with new partners. The practitioner and Tommy’s mother discussed ways in which AAC might support Tommy in participating more autonomously in the soccer activities, perhaps even turning it into a new microsystem for Tommy. They discussed adding vocabulary to promote Tommy’s ability to communicate with other siblings who attended the games. Given appropriate support, Tommy could develop healthy peer relationships both by sharing common experiences (e.g., adding vocabulary phrases like: “Do you like soccer?”), and by stating his own boundaries (e.g., “I don’t want to talk right now”). When he knew that his boundaries would be respected, Tommy eventually grew more comfortable initiating conversations with peers. Providing Tommy with a means to respectfully decline to participate also addressed Sam’s concerns about the game being used for therapeutic purposes that set their family apart from the others.

Identifying the family characteristics and dynamics

Dynamics within the family had also changed. Family members continued to find meaning in their preferred structure and predictable routine but were more likely than before to relax some of the structure and adapt their time to individual and group needs. For example, they continued to maintain structured routines such as family dinners, but flexibility was required for certain weeknights due to Sam’s scheduled soccer practices. Tommy’s mother scheduled weekend hang outs with Leo, but the day and time depended on Sam’s soccer games. The structured play time between the siblings after school was no longer possible due to individual after-school needs. For example, some days Sam needed to be driven to soccer practice, while other days Tommy needed to be taken to speech therapy. Tommy showed an increased interest in being an active participant in family discussions about how to achieve these family goals. The family indicated that it was important to them that Tommy increase his ability to express himself in order to share his opinions and feelings on family dynamics and activities.

Implications of the genogram for Tommy’s AAC

The practitioner used the self-created genogram to increase Tommy’s mother’s awareness of his growing number of communication partners and environments. As demonstrated at Timepoint 2, family dynamics had changed as a result of changing commitments and events (e.g., adding Leo; frequency of soccer practices/games; expanding social networks). At this evaluation, the team recommended continued use of the grid-based layout, including a QWERTY keyboard to support Tommy’s developing literacy skills and increase his active participation within the family microsystem. Tommy could still access familiar VSDs when he needed to communicate in environments that were less familiar or that induced stress for him (e.g., transitioning between classes, transitioning out of recess back to work). He primarily communicated using his grid-based pages but on occasion preferred to view and activate visual scenes that he found comforting in times of stress.

Tommy’s family microsystem remained a relatively stable supportive part of his communication ecosystem. Tommy’s family continued to support the use of the tablet with AAC app, working together to integrate the system because of their desire for Tommy to participate fully in the family. Both Tommy’s mother and Sam had agreed to invest resources of time and energy to meet with the practitioner in order to become familiar with the changes to Tommy’s AAC system and provide vocabulary recommendations. To support the expansion of Tommy’s communication and the family’s preferred structure, the practitioner worked with the family and Tommy to determine how Tommy’s AAC device could be integrated into additional predictable routines, including family game night and Sam’s soccer games.

The practitioner worked with Tommy’s mother and Sam to determine vocabulary that Tommy might need to talk about what was happening on different days. They included vocabulary related to activities such as driving Sam to soccer, watching television, playing video games, having a snack, going to speech therapy, or going to the store. This allowed Tommy to communicate about his own and the family’s activities. Furthermore, the ability to communicate about different possibilities helped to decrease stress by allowing Tommy to ask what he could expect each afternoon. The practitioner also recommended promoting communication with Tommy’s non-family microsystems (e.g., peers, school staff), and initiated a discussion about Tommy’s favorite video games to play with Leo to determine appropriate vocabulary programming.

Timepoint 3: High school/postsecondary transition period (age 20)

At his third evaluation, Tommy continued to receive special education services and was nearing the end of high school. He used an electronic tablet with a communication app and had grown comfortable taking his AAC device everywhere and communicating independently with a range of familiar and unfamiliar partners. Tommy was now also working as a cashier and stocker at the school’s student store and used his device across work environments. He spelled well using the QWERTY keyboard, supplemented by grid displays with preprogrammed phrases for frequent use (e.g., “What’s for dinner?” and “I’m going to bed now”). He regularly communicated in novel simple sentences. At this timepoint, Sam lived with a partner about a 3-hr drive away. Tommy and Sam saw each other in person every few months and they occasionally exchanged emails and messages. Tommy and both of his parents still lived in the same home. Tommy continued to feed the dog but described the family pet as “Dad’s dog” because it preferred to sit near the father. Tommy and Leo were still friends and played video games together often.

Creating the genogram

Micro- and mesosystems

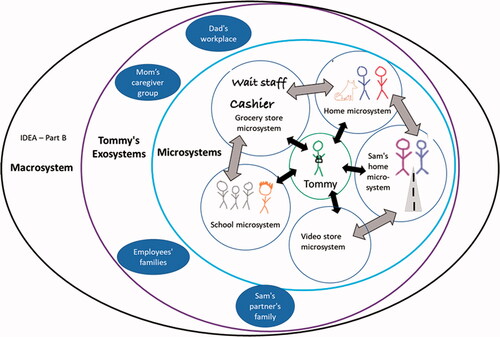

Tommy again worked with the practitioner to design a self-created genogram (). After Tommy created the genogram, his mother was invited to discuss the ecological systems that played a role in Tommy’s life. During the genogram creation, Tommy received support from the practitioner in the form of open-ended questions such as, Who else is important to you? Allowing Tommy to create his own genogram fostered a sense of autonomy and independence. Inviting Tommy’s mother to discuss the genogram allowed for continued empowerment of the family, informed the family about which people and contexts were important to Tommy, and raised awareness of communication opportunities throughout his day.

Figure 3. Tommy’s System at Timepoint 3 (High School/Postsecondary Transition) based on self-created Genogram. Note. IDEA: Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. Arrows represent interactions. Solid black arrows indicate Tommy’s relationships with his microsystems, and gray arrows indicate mesosystem relationships.

For this genogram, Tommy drew himself, his mother, his father, and the dog. He acknowledged that Sam was still important and a regular part of his life by continuing to draw Sam on his genogram. Tommy indicated that travel would be required to see Sam and their partner by drawing a schematicized road (a triangle with divided lines in the middle, see ) to get to them. Tommy also added his school (which included Leo) as well as his preferred/desired social and work environments (grocery store and video store) to his growing set of microsystems.

Tommy's family and school team implemented a transition plan in anticipation of graduation. Both Tommy’s mother and a teacher started to investigate possibilities for supported employment at a local grocery store. If that were to happen, the grocery store workers would become a new microsystem. The kinds of communication that would be needed to connect the family and the grocery store would be a new mesosystem.

Because Tommy frequently took trips to local stores and restaurants to target goals for developing life skills, the practitioner used open-ended questions such as, Where are some places that you take trips with your class? Tommy used his AAC device to respond (with some prompting) to use a new vocabulary grid related to community outings to support his spelling. To support Tommy’s growing understanding of his diversifying microsystems, the practitioner printed a variety of words related to vocational activities so that Tommy could select these for his genogram during construction of the genogram. Tommy and his mother now saw a more complete visual representation of the many communication partners and environments that Tommy encountered regularly. For Tommy, this visual created a sense of empowerment by showing him the wide variety of people with whom he could communicate independently.

The practitioner also discussed potential job opportunities in the community, asking, Tommy, where do you think you would like to work? Tommy used his AAC device to say, “Grocery store.” The practitioner then reviewed the self-created genogram with Tommy and discussed that once he graduates from school, the people who work with him at the grocery store could become a new microsystem. This could help prepare Tommy for the transition out of school, empower him to use his communication device with more partners, and increase awareness of networks that would support him in the future.

Exosystem

Finally, the practitioner drew one last circle to symbolize Tommy’s exosystem, representing settings where Tommy did not regularly interact but that could affect Tommy. This included Sam’s partner’s family (with whom Sam would spend alternate holidays, thus reducing time at Tommy’s home), and his father’s workplace. In the case of the latter, his father had been awarded more flexible work hours, meaning that he actually had more time to spend with Tommy and the family. Tommy’s father’s increased availability meant that his mother was able to join a caregiver group. She learned valuable information from other parents in this group about strategies she could implement to help Tommy transition from school to employment. These are both examples of positive effects that Tommy’s exosystems (Dad’s work, Mom’s group) had on his experiences.

Identifying the family characteristics and dynamics

The interview for the genogram revealed that, in secondary school, Tommy had developed a fondness for cooking. He went to the grocery store with his mother on Mondays to get ingredients for a meal to cook that evening. On other weeknights, Tommy typically did homework, played video games, or watched TV. His father still worked full time, but now had more flexible hours, while Tommy’s mother continued to maintain the household and to initiate the routines of the family. Tommy’s father supported her to achieve the family goals. The family was aware that Tommy was preparing to transition out of school into the wider community. Previously, Tommy relied on the family routine created by someone else to determine what would happen next. Now, due to the consistent incorporation of his AAC device within the family context, he exercised control and input about these routines. Tommy’s mother sometimes used daily visual schedules within the home to help Tommy understand expectations; however, Tommy was able to negotiate or offer alternative suggestions. His family members responded appropriately when he communicated a choice, by either honoring his decision or offering alternative options. For example, if his mother told him it was time to do his homework, Tommy would sometimes access his AAC device to communicate, “I want to play video games” or “Let’s go to the grocery store.” If he was scheduled to go to the grocery store with his mother after school but communicated that he felt tired, his mother offered him the option of going to the grocery store on a different day that week.

Implications of the genogram for Tommy’s AAC

The team considered the functional life skills and community activities that are needed to live independently in society. Grocery shopping was identified as a priority. Whenever Tommy wanted to cook a recipe, he took a screenshot from a YouTube video of someone else cooking it and showed it to his parents. Sometimes Tommy challenged the established routine by asking for his father instead of his mother to take him to the grocery store. Tommy navigated the store, found items, and paid for them. A grid display was programmed for dialog Tommy would need at the store, expanding his communication skills to new partners and settings in the community.

Tommy still wanted to hang out with Leo on the weekends. Therefore, the team considered vocabulary for his social activities with Leo, such as playing video games, bowling, and going to the movie theater. Expanded vocabulary helped Tommy to communicate across a greater variety of settings and people.

Now that Sam lived elsewhere, Tommy’s mother could allocate more time to taking him out in the community. Because the genogram had revealed that the grocery store was a viable job opportunity with motivating vocabulary, Tommy’s mother taught him to approach store employees to ask questions using his AAC device. This also helped prepare Tommy to respond to questions from customers should he obtain future employment in this setting. His mother expressed a desire for him to choose another setting to expand communication. Tommy chose a local video game store. He was familiar with the vocabulary from playing video games with Leo. Again, Tommy’s mother and the practitioner worked with him to communicate with novel communication partners via his AAC device.

Summary of case example

Tommy’s hypothetical case illustrates how the framework proposed in this paper can be used as a tool by members of an AAC team (e.g., behavior analyst, SLP, social worker) to support family-centered services across the lifespan and promote optimal uptake and use of AAC in both the home and other contexts. Furthermore, the case highlights the need to revisit the genogram across time, as an individual's needs, skills, and priorities change in response to changes that occur between and within the micro-, meso-, and macrosystems that influence functioning (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1979; King, Romski, & Sevcik, Citation2020). For example, at Timepoint 3, Tommy drew his AAC system within his genogram. This subtle change in Tommy’s self-representation may have indicated a shift in his identity and self-determination that was the result of his understanding of how his AAC system had influenced his life (Calculator & Black, Citation2009). Ideally, using tools such as self-created genograms to collect information about relationship dynamics to support family-centered practice will contribute to short- and long-term gains in confidence and autonomy for individuals with complex communication needs.

Discussion

Conversations between the practitioner, the person who uses AAC, and family during the creation of genograms have the potential to provide rich insight into the values, routines, and priorities of the individual who uses AAC and their family. This information allows the practitioner to understand the interaction styles between and within the family, as well as how the individual and their family operate on a daily basis. The individualization of this process provides a strong framework for the practitioner to engage in family-centered AAC services. The framework focuses on individuals taking an active role in the creation of the genogram, which empowers them to become an active part of the family. Perhaps even more powerful is the potential impact of nesting a self-created genogram within the various ecological subsystems (e.g., settings outside of the home).

The visual representation of the self-created genogram allows the practitioner and family to identify communication opportunities that would have otherwise been overlooked. Moreover, it has the potential to help identify where there might be communication opportunities between individuals and others in the larger social networks within which they interact. This underscores the importance of providing a voice to the individual who uses AAC to promote communication beyond just the family microsystem, leading to increased communication access in multiple environments for the individual who uses AAC.

Directions for future research

Additional research is necessary to examine the efficacy of applying the proposed framework to a real-world example, to refine the framework, and to study potential outcomes. For instance, self-created genograms may play a potential role in maximizing the engagement and contributions of the individual with complex communication needs in family-centered practices because they can use drawing, photographs, or their AAC system to assist in generating the genogram. Although using self-created genograms has promising research support in other disciplines (e.g., Piasecka et al., Citation2018), it is necessary to conduct research with individuals who use AAC to determine whether this framework would be similarly beneficial. Additional research is also necessary to evaluate whether the process of generating self-created genograms does in fact allow for more in-depth information about family structures and functioning than current/traditional approaches. If genograms do provide an AAC team with rich information about a family, their use might lead to improved family-centered practice and improved AAC uptake. Such benefits could be studied directly, by examining the types of information generated by traditional case histories versus those that have been informed by/produced from the self-generated genograms. Additionally, the self-created genogram might maximize the involvement of the individual who uses AAC. Research is required to determine the extent to which this framework helps individuals who use AAC develop this type of autonomy.

In addition, it is critically important to evaluate the social validity of the proposed framework (Schlosser, Citation1999). Such research would examine whether clients and their families are satisfied with the process of self-created genograms. Do families and clients feel that using self-created genograms does, in fact, create a richer family-centered approach? This research is critical to evaluating the value of the approach and, where necessary, adjust it for the unique communication profiles of individuals who use AAC. Other questions of social validity include (a) whether families perceive that they are receiving family-centered services while using the proposed framework, (b) whether individuals who require AAC perceive that they are being included as active participants in their communication plans, (c) perceptions of professionals implementing this framework, and (d) if the application of the framework would be important to individuals with complex communication needs and their families.

Conclusion

A tool such as self-created genograms may assist professionals in understanding how to center the family within their system and fill an important gap in current AAC services. The proposed framework is based on the foundations of the self-created genogram, family paradigms, and ecological systems theory. While the case composite is hypothetical, it offers an illustration of how the framework might be applied to an individual who requires AAC. Several key components (e.g., skills, areas of need, and social contexts of the target individual adjusted over time) can be compared to a recently published longitudinal profile of an individual who requires AAC by King et al. (Citation2020). For example, the skills, areas of need, and the social contexts of the target individual and his family within King et al. (Citation2020) adjusted over time. As a result, the individual’s self-determination and priorities evolved along with his AAC system. This parallels with the example of Tommy, and both offer practitioners a means to obtain important insights into family structures and dynamics that could help maximize success of AAC across settings.

Author note

Our proposed framework derived from a doctoral seminar on cross-disciplinary practices and the implications for AAC intervention.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Gregory Fosco, associate professor of Human Development and Family Studies at Penn State, for sharing a passionate guest lecture that generated our interest in family systems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baxter, S., Enderby, P., Evans, P., & Judge, S. (2012). Barriers and facilitators to the use of high-technology augmentative and alternative communication devices: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 47(2), 115–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-6984.2011.00090.x

- Binger, C., Berens, J., Kent-Walsh, J., & Taylor, S. (2008). The effects of aided AAC interventions on AAC use, speech, and symbolic gestures. Seminars in Speech and Language, 29(2), 101–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1055/s-2008-1079124

- Blackstone, S., & Hunt Berg, M. (2003). Social Networks: A communication inventory for individuals with severe communication challenges and their communication partners. Monterey, CA: Augmentative Communication, Inc.

- Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Calculator, S. N., & Black, T. (2009). Validation of an inventory of best practices in the provision of augmentative and alternative communication services to students with severe disabilities in general education classrooms. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(4), 329–342. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2009/08-0065)

- Connolly, C. M. (2005). Discovering “family” creatively: The self-created genogram. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 1(1), 81–105. doi:https://doi.org/10.1300/J456v01n01_07

- Crais, E. R., Roy, V. P., & Free, K. (2006). Parents’ and professionals’ perceptions of the implementation of family-centered practices in child assessments. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 15(4), 365–377. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2006/034)

- Crawford, M. (2020). Ecological systems theory: Exploring the development of the theoretical framework as conceived by Bronfenbrenner. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices, 4(2), 170. doi:https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100170

- Deutsch, M. L., & Hidecker, M. J. (2015). Family paradigm assessment scale (F-PAS) test-retest reliability. Mountain Scholar. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11919/2440

- Dunst, C. J. (2002). Family-centered practices: Birth through high school. The Journal of Special Education, 36(3), 141–149. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/00224669020360030401

- Dunst, C. J., Johanson, C., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. (1991). Family-oriented early intervention policies and practices: Family-centered or not? Exceptional Children, 58(2), 115–126. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/001440299105800203

- Hidecker, M. J. C., Jones, R. S., Imig, D. R., & Villarruel, F. A. (2009). Using family paradigms to improve evidence-based practice. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 18(3), 212–221. doi:https://doi.org/10.1044/1058-0360(2009/08-0011)

- King, M., Romski, M., & Sevcik, R. A. (2020). Growing up with AAC in the digital age: A longitudinal profile of communication across contexts from toddler to teen. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 36(2), 128–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2020.1782988

- Leibowitz, M. (2013). Interpreting projective drawings: A self-psychological approach. New York: Brunner/Mazel.

- Lev-Wiesel, R., & Zeevi, N. (2007). The relationship between mothers and children with Down syndrome as reflected in drawings. Art Therapy, 24(3), 134–137. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07421656.2007.10129420

- Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Caron, J. (2019). New and emerging AAC technology supports for children with complex communication needs and their communication partners: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(1), 26–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2018.1557251

- Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Jakobs, T. (2014). Developing AAC technology to support interactive video visual scene displays. RERC on AAC: Rehabilitation Engineering Research Center on Augmentative and Alternative Communication. https://rerc-aac.psu.edu/development/d2-developing-aac-technology-to-support-interactive-video-visual-scene-displays/

- Mandak, K., & Light, J. (2018a). Family-centered services for children with ASD and limited speech: The experiences of parents and speech-language pathologists. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1311–1324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-017-3241-y

- Mandak, K., & Light, J. (2018b). Family-centered services for children with complex communication needs: The practices and beliefs of school-based speech-language pathologists. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 34(2), 130–142. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2018.1438513

- Mandak, K., O'Neill, T., Light, J., & Fosco, G. M. (2017). Bridging the gap from values to actions: A family systems framework for family-centered AAC services. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33(1), 32–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1271453

- Milewski-Hertlein, K. A. (2001). The use of a socially constructed genogram in clinical practice. The American Journal of Family Therapy, 29(1), 23–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180125996

- Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1129720

- Piasecka, K., Slusarska, B., & Drop, B. (2018). Genograms in nursing education and practice a sensitive but very effective technique: A systematic review. Journal of Community Med Health Education, 8(6), 2161–0711. doi:https://doi.org/10.4172/2161-0711.1000640

- Reja, U., Manfreda, K. L., Hlebec, V., & Vehovar, V. (2003). Open-ended vs. close-ended questions in web questionnaires. Developments in Applied Statistics, 19(1), 159–177.

- Schlosser, R. W. (1999). Social validation of interventions in augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15(4), 234–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619912331278775

- Schlosser, R. W., & Koul, R. (2015). Speech output technologies in interventions for individuals with autism spectrum disorders: A scoping review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(4), 285–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2015.1063689

- Turabian, J. L. (2017). Family genogram in general medicine: A soft technology that can be strong. An update. Research in Medical & Engineering Sciences, 3(1), 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.31031/RMES.2017.03.000551

- Zaidman-Zait, A., Yechezkiely, M., & Regev, D. (2020). The quality of the relationship between typically developing children and their siblings with and without intellectual disability: Insights from children's drawings. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 96, 103537–103512. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2019.103537