Abstract

The closure of schools and healthcare facilities across the United States due to COVID-19 has dramatically changed the way that services are provided to children with disabilities. Little is known about how children who use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC), their families and their service providers have been impacted by these changes. This qualitative study sought to understand the perspectives of parents and speech-language pathologists (SLPs) on how COVID-19 has affected children, families, services providers and the delivery of AAC-related communication services. For the study, 25 parents and 25 SLPs of children who used aided AAC participated in semi-structured interviews, with data analyzed using qualitative thematic analysis. Parents and SLPs highlighted wide disparities in how children have been impacted, ranging from views of children making more progress with communication and language than before the pandemic to worries about regression. A complex system of factors and processes may explain these differences. COVID-19 will have lasting impacts on the lives of children with complex communication needs. This research highlights the crucial role of family-service provider partnerships and access to quality AAC services for children during the pandemic and into the future.

Introduction

The spread of COVID-19 and efforts to address the public health crisis have disproportionality impacted certain groups in the United States (US) and across the globe. Children with disabilities, families and their educators and service providers are likely to be among those who are most greatly impacted by service changes or service loss during the pandemic, particularly because of the critical roles that educational and related services play in the well-being and development of children with disabilities (Aishworiya & Kang, Citation2021; Constantino et al., Citation2020; White et al., Citation2021). As the pandemic continues, research and advocacy efforts are needed to understand the impact of the pandemic on children with disabilities and their families, to identify effective measures to improve the quality of life for these children and to reimagine more effective supports and services for the future.

In the US, speech, language and communication services for children from ages 3 to 21 are typically provided through a face-to-face format in school settings, including for children learning to use augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2020). In addition to school-based services, some children and youth receive additional services in clinic-based or private practice settings, typically with the cost covered by medical insurance, parent out-of-pocket pay, or a combination of both (Reilly et al., Citation2016). Although parent participation in therapy across these settings varies according to both policy and preference, prior research has shown that there is a gap between what professionals and families believe about working with families, and what actually happens in practice, with parents of younger children perceiving their child’s services to be more family-centered than parents of older, school-age children (Mandak & Light, Citation2018). In schools, family perspectives are not always accessible during service provision (Goldbart & Marshall, Citation2004). Therefore, traditional school-based services have not always included goals that match the family’s priorities (Mandak & Light, Citation2018), leading to difficulties maintaining progress across both school and home settings (Granlund et al., Citation2008).

As schools and clinics in the US and worldwide closed their doors to in-person services to control COVID-19, many children with disabilities lost access to critical services. Consistency of services is essential for these children, and disruptions may leave them at risk for learning loss, regression, or increases in behavioral challenges (Constantino et al., Citation2020; Masonbrink & Hurley, Citation2020; Provenzi et al., Citation2020). In a survey about service disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic, Jeste et al. (Citation2020) found that 74% of caregivers of children with disabilities in the US and 78% of caregivers abroad reported losing access to at least one therapy or education service. Even more troubling, 30% of families in the US and 52% of families abroad reported losing all services. In a separate report of caregivers of children and youth with autism, White et al. (Citation2021) found that 80% of parents and caregivers reported disruptions to their child’s special education services, and 88% reported disruptions to speech-language services. Furthermore, 64% of caregivers reported that the disruptions to services had a negative impact on their children, and over 70% of caregivers reported that they experienced extreme or moderate stress due to disruptions in their children’s services.

Around much of the world, the most common solution to ameliorate and prevent service disruptions during the pandemic has been to transition to telepractice, which can allow greater continuity of care without increasing COVID-19 risk (Fong et al., Citation2021; Pavičić Dokoza, Citation2020; Smith et al., Citation2020). Telepractice – which is defined as the use of technology for the delivery of professional services from a distance – has a modest but growing body of literature supporting its promise for providing therapeutic and educational services to children with developmental disabilities and their families (Akemoglu et al., Citation2020; Camden & Silva, Citation2020; Simacek et al., Citation2017). Numerous potential benefits to telepractice have been noted, including reduced wait time for services, alleviated scheduling challenges, reduced travel time for families and service providers, and improved ability for providers to focus on supporting children’s skills within natural environments, such as their home (Casale et al., Citation2017). Because few service providers were using telepractice to provide speech-language services prior to the pandemic, however (Tucker, Citation2012), the switch to telepractice in response to COVID-19 was rapid and forced – intensifying challenges that had already been previously identified with telepractice. For example, service providers need but may not have access to support to implement telepractice (e.g., equipment, training) due to quickly changing practices and policies (Biggs, Rossi, et al., Citation2022; Camden & Silva, Citation2020). Additionally, some children with disabilities have difficulty engaging via a computer screen or are not able to independently operate technology. In these cases, a family member may become a necessary facilitator for telepractice (Snodgrass et al., Citation2017). Although providing a facilitator could lead to a potentially beneficial shift in increasing family-service provider partnerships and the use of coaching services, this may not be feasible for all families.

Relatedly, the stress on families of children with disabilities during the COVID-19 pandemic is important to consider. Parents have identified “silver linings” to changes in routines during the pandemic, including more time spent together, a slower pace of life and personal development (Neece et al., Citation2020); however, changes in routines may place additional burdens on parents, and many parents of children with disabilities who have greater support needs already have greater levels of stress (Neece et al., Citation2012; Woodman et al., Citation2015). Increased expectations for parents to facilitate telepractice may leave them feeling overwhelmed (Jeste et al., Citation2020), which could amplify stress and have cascading impacts on parent and child well-being (Aishworiya & Kang, Citation2021; Daks et al., Citation2020; White et al., Citation2021). In light of the loss of services, many parents from diverse ethnic, linguistic and socio-economic backgrounds have identified caring for their children with disabilities at home as their biggest challenge during the pandemic (Neece et al., Citation2020). Similar findings are emerging worldwide, such as in Italy, where preliminary data suggests parents of children with disabilities experience higher levels of burnout and less social support than other parents (Fontanesi et al., Citation2020).

Furthermore, families with limited access to technology and internet service (e.g., those in rural or underserved areas or living in poverty) are at the greatest risk of being cut off from services due to the rapid shift to telepractice (Aishworiya & Kang, Citation2021; Provenzi et al., Citation2020). For example, even before the pandemic, families from low-income backgrounds identified challenges with remote learning that included access to technology (Colvin et al., Citation2022). During the COVID-19 pandemic, schools in the US utilized varied methods of remote learning, including hybrid instruction, on/off days in school, synchronous videoconferencing classes and therapy sessions, and asynchronous learning (e.g., work packets or recorded presentations), both for regular and special education services (Colvin et al., Citation2022). As an additional source of inequity, private schools tended to return to in-person instruction more rapidly than public schools, even within the same region (Miller, Citation2020).

Although a full understanding of the impact of educational disruption during the COVID-19 pandemic remains unknown, emerging data are beginning to confirm what would be expected: The greatest negative impacts from service disruptions and inequities in technology access and learning supports are experienced by children from historically marginalized backgrounds, including students from low-income households, students for whom English is not their primary language, students of color and students with disabilities (Colvin et al., Citation2022). These challenges highlight the urgency of protecting the rights of children with disabilities and their families to access quality services and support. Communication services are especially important for children who have complex communication needs and are unable to use speech to meet their communication needs (Brady et al., Citation2016). These children can benefit from aided AAC, which may include picture symbols on communication boards, speech-generating devices, or mobile applications for communication (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020).

In a survey of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) in the US related to the use of telepractice for children who use aided AAC, for example, nearly 75% reported that one or more children on their caseload had lost communication services as a result of COVID-19 (Biggs, Therrien, et al., Citation2022). The primary reasons were that families did not want telepractice services or had limited access to the required technology, scheduling was not successful, or SLPs did not know how telepractice could be used effectively. Furthermore, SLPs identified intersecting factors impacting service effectiveness related to different stakeholders (e.g., access to AAC; child engagement and behavior; family involvement; SLP knowledge, skills and resources), as well as broader factors related to technology, policies and funding and the sudden shift in service delivery (Biggs, Therrien, et al., Citation2022).

Communication is an essential human right; as such, there is a crucial need for research into how services for children who use AAC have been impacted by the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. To that end, this study sought to understand the perspectives of parents of children who use AAC and SLPs who deliver AAC services, on how COVID-19 has affected children, families, services providers and the delivery of AAC-related communication services. The following questions were addressed: How do parents and SLPs characterize the impact of COVID-19 on their children and themselves? and What are the processes and factors that interact to bring about these impacts?

Method

This study was conducted within a larger project investigating the experiences of SLPs and families of children who used aided AAC during COVID-19. The interdisciplinary research team consisted of faculty and students in the fields of communication science and disorders and special education who reflected on personal biases and positionality throughout the research process through reflexivity, critical reflection and team debriefing.

Participants and recruitment

Parents and SLPs of preschool (3- to 5-years-old) through school-aged (5- to 21-years-old) children and adolescents who used aided AAC from across the US were invited to participate. Recruitment information was emailed to community providers (e.g., pediatric and AAC specialty clinics), personal contacts and listservs of SLPs, and posted on social media (i.e., Facebook, Twitter). Potential participants completed a short interest form via Qualtrics to obtain information on demographics and characteristics of their child or children who used aided AAC on their caseload. This information was used to stratify participants by four priorities to obtain a diverse sample with representation across (a) grade levels (i.e., preschool, elementary, middle, high), (b) community type (i.e., suburban, urban, rural), (c) states considered high-incidence versus low-incidence for COVID-19 spread as of June 1, 2020 (John Hopkins University of Medicine, Citation2020) and (d) disability labels and types of AAC systems (non-electronic vs. electronic). These priorities were considered to be ones that might create more bias in our outcomes, aimed at determining the impact of the transition to telepractice if left unexplored.

The short interest form received 205 responses (123 SLPs, 82 parents). Of these potential participants, 25 parents and 25 SLPs were selected to participate. Although the sample size was a practical one given time constraints, research on qualitative data saturation, or the number of interviews analyzed until no new themes are developed, has found that in small populations, 12 interviews is sufficient (Ando et al., Citation2014; Guest et al., Citation2006). Because the goal was to capture perceptions of impacts from participants who may have had disparate experiences, we chose to double that number for each group (parents and SLPs). Participant characteristics can be found in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

Research design

This descriptive qualitative study (Sandelowski, Citation2000, Citation2010) involved semi-structured interviews and content analysis (Patton, Citation2015). The qualitative description aims to offer clear, comprehensive descriptions of phenomena that are “data-near” (Sandelowski, Citation2010, p. 78), meaning-producing findings that are closer to the data and less interpretative than those from other traditions such as phenomenology or grounded theory – albeit still interpretative because all qualitative research is interpretive. All required approvals were obtained from the Institutional Review Boards of Florida State University and Vanderbilt University.

Materials

Materials involved (a) a short interest form, and (b) an interview guide. The short interest form asked for basic information about the demographics and characteristics of their child or children who used aided AAC on their caseload.

The research team collaboratively developed interview guides for parents and SLPs that were aligned to ask similar questions of both groups. In accordance with the broader project, questions were organized into three main sections: (a) AAC services during the COVID-19 pandemic, (b) Family-SLP partnership and (c) Barriers and facilitators to family–SLP partnership. Additional questions were positioned at the start and end of the interview to build rapport and to wrap up (see Supplemental Materials for full interview guide). Prior to data collection, the research team piloted interviews with one parent and one SLP who were not part of the study, using their feedback to make minor wording adjustments.

Procedures

Data collection

Data were collected through individual, semi-structured interviews over Zoom, a secure videoconferencing platform. Because the COVID-19 pandemic was ongoing during data collection, face-to-face interviews were neither ethical nor safe. Each interview was recorded and lasted approximately 45 min (range: 15–90 min; M = 43); participants received a US$40 gift card for participating. One of two graduate research assistants conducted each interview under the supervision of the authors, who provided training in qualitative interviewing. The interviewers used the interview guide to maintain consistency while adopting a conversational style that involved asking unscripted follow-up questions to encourage participants to clarify or expand on their responses. Interviews were conducted between July and August 2020.

Data analysis

Recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, and three research assistants de-identified and checked transcripts for accuracy. Data were analyzed using an inductive and iterative process, guided by procedures outlined by Saldaña (Citation2021). Multiple strategies were used to support credibility and trustworthiness, including a team-based approach to analysis, iterative rounds of coding to progressively refine findings, and searching for confirming and disconfirming evidence (Patton, Citation2015; Saldaña, Citation2021).

The first round of coding was structural, which involved labeling and indexing longer excerpts for further analysis based on specific research questions (Saldaña, Citation2021). Five structural codes were used to address research questions across the larger project, one of which focused on Impact (i.e., impact on the child, family and SLP). A codebook containing structural code names, descriptions and memos was developed. For each transcript, two randomly assigned coders independently read and coded each transcript and then met with a randomly assigned third member of the research team to discuss disagreements and reach a consensus on final codes.

The second round of coding involved importing transcripts and consensus codes into NVivo (version 12.6.1). This involved open coding, also sometimes called initial coding (Saldaña, Citation2021), for all excerpts within the Impact structural code. Through a series of meetings, the first and second authors marked excerpts with one or more open codes, using constant comparison to compare each new piece of data with all other data to discern whether it should be assigned a new code or if it was associated with a previously mentioned idea (Patton, Citation2015). During open coding, each new code was added to an electronic coding manual along with a description and accompanying memos or examples. At the end of open coding, the researchers made 794 code applications to excerpts across 23 different codes in NVivo.

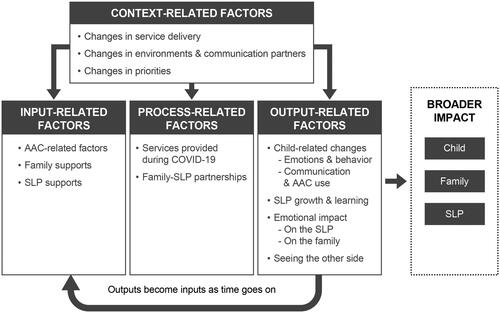

Following open coding, the third round of coding began by having all research team members critically review reports of the coded data. Each team member independently identified connections across codes and then met to group the codes into categories and themes. Through this collaborative analysis, the team noticed connections between the data and the context-input-process-output model (CIPO; Scheerens, Citation1990). This model specifies that outcomes (Output) come about through Input factors by means of Process factors. Furthermore, the model specifies that input, process and output factors are all influenced by Context factors. The CIPO model was originally developed by Scheerens (Citation1990) to explain school functioning and it has typically been applied to explain the system, school or classroom-level educational outcomes as opposed to outcomes for individual students or their families; however, this model seemed to fit the data to explain how parents and SLPs saw different factors and processes coming together to bring about both shorter and longer-term impact; therefore, data were reduced by applying the CIPO framework in the third round of coding. Codes were loosely grouped for further analysis and re-analyzed to refine understanding, searching for confirming and disconfirming evidence, using diagraming and memoing as analysis tools. At the end of the analysis, the coding framework involved 188 code applications related to Broader Impacts; and 652 code applications related to how context-, input-, process- and output-related factors were driving these impacts.

Results

Data collection and analysis yielded insight into parent and SLP perspectives of impact, as well as how these outcomes were tied to many different factors and processes within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic; this is described as the larger system of impact. The interactions among these factors can be seen in .

Figure 1. System of factors contributing to broad outcomes. AAC: augmentative and alternative communication; SLP: speech-language pathologist.

Broader impacts

Impacts on children who use aided AAC

Participants noted that long-term impacts on children were hard to determine and complex. The impacts varied not only widely from child to child but also within each child; parents and SLPs often described children making great strides in one area but very little progress, or even regressing, in others. For example, one SLP (38) explained:

Three [children] that have made leaps and bounds, I should be super celebrating. But then I know I have a bigger percentage that are not, and that possibly even regress… The kids we’re not seeing directly, we’re having a decline.

A parent (53) talked about “pros and cons” for her son. She explained they were able to have more of some services because scheduling was easier, saying, “I’m really grateful for that… so definitely some pros”. She went on to add, “But the cons of watching him somewhat regress because I know he’s not getting that structure, he’s not getting that challenge. … So just to say it’s been challenging is an understatement I think”. For many of the participants, fear of regression was high. Parents and SLPs discussed challenges with services going virtual so quickly, including children being left without access to services. One parent (52) shared, “We have no more therapies, currently. We don’t get speech. We don’t get occupational or physical therapies. We get no therapies”. When asked about the impact on her daughter, she talked about regression, sharing, “It pretty much went back to the way that it was before… we reverted back to the old way”. Participants were most likely to talk about regression in goal areas that were harder to address with stay-at-home orders, including peer interaction and academics. One SLP (85) shared:

I just feel very disappointed and worried about going back to school because I can only imagine the limited routines. And we’re going to have to start back over at square one in identifying, ‘This is what you do at school.’

A parent (26) described, “I just saw that [child’s name] was really burgeoning and growing so much over the course of the school year of 2019 and into 2020, and she became just a couch potato in March”.

Other participants reported that children were maintaining skills or progressing, even if the progress was slower. For some, their feelings were positive. One SLP (15) shared, “Honestly, my biggest priority right now is that the parents and families feel supported… It’s hard right now to make much progress”. She went on to explain, “So the fact that none of my kids are regressing right now, the fact that they can still attend the sessions, if I can get them to use the device at all, I consider it a win right now”. Others were frustrated or concerned, especially if they had been seeing children experience rapid growth prior to the shutdown. One parent (48) said, “I would have expected her to have been more advanced by now had she been receiving actual [face-to-face] therapies”.

Still, other parents and SLPs noted (typically with surprise) that children had made gains in communication during the COVID-19 pandemic. Said one parent (18): “It’s actually gotten better. And I know that sounds crazy, but we’ve had more opportunities to model [AAC] here at home. … It just seems more naturally flowing here at home”. An SLP (84) remarked that the “amount that they’re using their device is just going through the roof!” One parent (22) noted that her son’s friend told her, “He just walks around at school like that thing [AAC device] just has to hang around his neck and he doesn’t ever use it. And look how much he can talk with it!” This parent described seeing a “boom in his language” and remarked that this has been a “hidden blessing” of the COVID pandemic. In other situations, SLPs described seeing new generalizations of communication skills from school to home. One SLP (84) noted, “I think that the gains that we’re making are more impactful because everybody is home and so they need to know what their kids need or want or think or feel more”. Another SLP (15) shared a similar sentiment, thinking about implications for the future:

I think long-term-wise, most of my kids are going to be better off because when they stop seeing me, the parents are going to have the skills and the knowledge that maybe they wouldn’t have if we weren’t spending so much time on the phone and emailing, and virtual zooming together.

Impacts on families and SLPs

Impacts for many parents were related to changes in how they conceptualized their own role in their child’s communication, particularly with the use of an AAC system. One parent (34) described being “thrown in” to learning about her child’s AAC system during the pandemic but that it was “kind of a good thing”. She explained:

Otherwise, you just end up relying on somebody else… but now I know how to do it. We can take ownership of it ourselves and start to figure out how we can make it meaningful to our family and for her.

An SLP (32) remarked that many parents “… are having their ah-ha moments, especially as they’re being home with their kids more because they’re not at work; they’re at home. They’re using their language more. And it’s clicking for a lot of these families”.

Although SLPs and parents typically reported wanting to go back to face-to-face services, positive impacts helped them identify changes they wanted to make going forward. Many SLPs and parents described working more closely with one another during the pandemic than they had before, and as a result, they wanted to know how increased trust and collaboration could continue post-pandemic. A parent (45) shared that she would be interested in observing the SLP once her child returns to school, saying:

If I could observe versus— via Zoom even… I could just see and then talk with them about some things. I think that that could be really useful for me to have trust and faith in what they’re doing and also give useful feedback.

One SLP (15) shared, “I think every single AAC user I have worked with, their family has talked about how great it is that they’re learning so much now”. She went on to explain, “And I probably should have been incorporating families a whole lot more always. … That is definitely a takeaway from this”. Working with families during the pandemic also gave SLPs perspective about what they ask of parents. SLP 28 explained:

I think it’s more realistic now that I see what happens with families at home with it. So, I think I can change, modify my expectations. And it’s not a bad thing. I just have to be realistic…I feel maybe prior to the pandemic, I could have been slightly judgmental, like “Oh, this person, parent’s not doing this”. And now I see how hard these parents are working. And it definitely has changed in a positive way…They have a bigger voice now. I will be reaching out to them more often.

Factors within the system of impact

Context-related factors

Changes in contextual factors included changes in service delivery (e.g., telepractice and virtual learning, policies and funding), communication environments and partners, and priorities (see ). The first context-related factor, changes in service delivery, is related to the rapid shift when lockdowns first began in the US in March 2020. One SLP (1) remarked, “It was very quick and very— not a lot of ground rules, not a lot of things were set up. It was just kind of finding things out as you go”. This resulted in challenges as schools, clinics and third-party payers (e.g., insurance, Medicaid) had to develop new policies on the appropriate use of technology and payment for services. The second factor, changes in communication environments and partners, also came with COVID-19. Because children were at home more, parents and SLPs described how it was easier to focus on communication with parents and siblings, but simultaneously more challenging to focus on communication with peers and other communication partners. One parent (34) noted, “It was pretty isolating. She’s a very social kid… and that was hard because she thrives on being around other people”. Finally, the context of the pandemic also brought the third factor, changes in priorities, for parents and SLPs. Parents reported prioritizing time together as a family, and SLPs reported prioritizing the provision of emotional support to families. As one SLP (15) said:

My biggest priority right now is that the parents and families feel supported, and they know that I’m there to help them in any way that I can…as far as pushing academics or pushing goals, I’ve really taken a backseat on that.

Input-related factors

Children, their families and SLPs were all described as bringing personal characteristics or other factors that influenced the impact of communication services (see ). The first type was AAC-related factors. For example, some children had just received an AAC system or were participating in an AAC evaluation when the shutdown began. One parent (57) said, “It’s hard” and that “right before COVID we were jumping into the AAC world”. AAC access itself was a challenging factor. Some children lost access to school-provided devices, often using communication boards as back-ups. SLP 42 described “kind of scrambling because he didn’t really have any form of communication at home other than screaming and grabbing the communication partner and leading them to what he wanted”. Additionally, some SLPs noted that telepractice was easier or harder depending on the characteristics of the child’s AAC system. For example, one SLP (61) said, “It depends on their access method. So, my direct select kids, they’re fine… switch kids, that’s hard for parents. That’s a job. That’s a challenge. That’s a whole other level”. Another explained how difficult it was to “program an eye gaze on the other side of the computer” (SLP 54). Other input-related factors were family support and SLP support. Parents and SLPs noted that having good support systems (e.g., childcare, family nearby, administrative support and helpful colleagues) decreased stress and helped them provide effective communication services. Other participants lost support with the pandemic. One parent (8) described the toll of “having it all on me and my husband”, explaining, “I mean obviously we are not going to risk our health or [child’s] health just because we need a break”. An SLP (72) shared,

I think the initial challenges were—I think we all felt isolated. I think we all felt exhausted for a really, really long time like your head just wanted to explode, and just probably, for us, you go session to session, and we’re supporting families with really complex kiddos.

Process-related factors

Participants also described more action-oriented factors, which were categorized into two process-related factors (see ): (a) services provided during COVID-19, and (b) family and SLP partnerships. Taken together, the two factors seemed to act as the strongest drivers for whether outcomes involved positive or negative impacts. In the first category, services varied widely, including whether children lost services, whether the types and modalities of service delivery met the needs of children and their families (e.g., telepractice vs. in-person; direct vs. coaching services) and the degree of collaboration with other professionals.

Some families experienced a complete loss of services due to the pandemic. One parent (18) explained, “We basically really didn’t get speech services. She’s, I think, emailed us one activity during distance learning, and that was it”. Other parents described opting out either because of scheduling challenges or because they didn’t feel that their child was benefitting. One parent (68) said, “He does not do well with the teletherapy kind of things, so we had to sign a waiver with the school district saying that we were declining the speech from there”.

Furthermore, SLPs discussed disparities that challenged access to services. SLP 1 shared, “We had a program to loan out ChromebooksFootnote1, but it was kind of a thing where parents had to do the reaching out… and a lot of parents were either uncomfortable doing that or really weren’t sure how”. She went on to explain an opportunity for free internet access through a company, explaining:

It turned out there were a lot of caveats to that. Like my undocumented [immigrant] families don’t have it. I had a kid that I was really hoping would get it, but then apparently his mom had unpaid bills so she couldn’t get it.

When services were being provided, many parents and SLPs reported feeling like their children or their clients were “not really getting that much of anything out of the computer” (SLP 28). Other participants, however, described strategies that supported effective telepractice, such as using shared reading, videos and interactive activities for direct services to children; and finding ways to partner with families, such as by offering coaching or consultation services and using a variety of technologies and options that were responsive to families’ needs and preferences. The degree of collaboration was another source of variation, and some parents discussed how the pandemic amplified a lack of cohesion across providers. One parent (16) explained that she “pretty much begged” her child’s school providers to talk with her child’s private SLP, “because my main goal was just to get them working on the same page, so they weren’t going in opposite directions, but for whatever reason, the school was just incredibly resistant to that”. On the other hand, Parent 32 described the strong collaboration between her child’s school-based SLP and teacher, saying, “They’re working together. They’re planning lessons together. I’m sure that the teacher has learned a great deal from her speech therapist and vice versa… she’s got a great team”.

The second within-process-related factor was family and SLP partnerships. One parent (29), said:

We have a really good communication with the team that she works with. And we collaborate. And that’s a huge, huge bonus, that we just bounce ideas off of each other. And we try to come up with the best plan.

Participants noted the different nature of these partnerships prior to and during the pandemic. This shift was positive for some but difficult for others. Strong partnerships did not simply involve one-way information from the SLP to the parent, nor rely on models of intervention that required the parents to act as if they were the hands in service of the therapist. Instead, the relationships between SLPs and parents were marked by more authentic partnership and responsiveness to one another. One SLP (8) said that she learned “not to shove everything down the [family member’s] throat”. She explained, “I think in the past, I’ve been guilty of it. When they come in, I’m like ‘Here’s this giant stack (laughter) of all these resources’”. She added that she has now begun “trying to meet parents in the middle”.

Within SLP-parent partnerships, the roles and contributions of both parties were clearly important. For parents, factors that shaped partnerships included perceptions about their role and other demands placed on them during the pandemic. Many parents felt overwhelmed by the stress of full-time caregiving along with other responsibilities such as their careers or other children. Parent 31 explained, “They offered Zoom calls, but because I was working and my husband was still working at home, we weren’t really able to participate in it”. Another parent (26) described, “I’m really tired. … We have to reserve our energy for what’s important, which is care providing for our kids, and then try and keep ourselves sane, and then everything else is extra”. Still, others found that they were able to focus more on supporting communication at home during the pandemic. Increasing the use of AAC modeling was brought up frequently. One parent (22) explained:

We’ve been able to model all the time, right? And while he had a fabulously wonderful team at school that was modeling and was trying, he’s not the only student in the class, right? … I think my role is to do everything that I can to facilitate his language during this time. And that just means me having to step up to the plate—all of us here in the house.

SLPs also discussed their own roles, including empowering families. One SLP (72) noted that she was more intentional than she had been previously with how she provided information to families: “if I look back on it [prior to the pandemic], the coaching was probably way more incidental or matter of fact where now we’re doing direct coaching”.

Output-related factors

Outputs was the term to describe shorter-term outcomes or changes, and these had transactional and self-reinforcing roles by cycling back into the system of impact over time. Related to the child, outputs were characterized as (a) changes in emotions and behavior regulation and (b) changes in communication and AAC use. Some parents talked about seeing increases in children’s anxiety, and many participants noted increases in challenging behaviors (self-injurious behavior, meltdowns, etc.). One parent (22) explained, “He’s had heightening anxiety since all of this, obviously. I think everybody has. But when you’re nonverbal it’s a little bit harder to explain that, right? So, it manifests in behaviors”. An SLP (1) said:

I have had some kids that have had some really large increases in challenging behavior, including one kid that never in the entire school year did I deal with a challenging behavior in a session. And since we’ve been doing remote, just about every session has been taken over by challenging behavior.

On the other hand, many parents and SLPs described positive changes in communication and the use of AAC. One parent (18) remarked, “We had to call a plumber, and he actually said, ‘Who help stop bathroom?’ And I was like, oh my gosh. He used to never ask questions”. In the case of both behavior and communication, changes for children in these areas seemed to function over time as factors that cycled back again as inputs. For example, when children had positive changes in communication, parents described this as reinforcing their own efforts to support their child’s communication (e.g., modeling AAC). However, increases in challenging behaviors or children’s anxiety were more likely to compound feelings of being overwhelmed for families, making family efforts to support communication more challenging and less likely to occur.

The output specifically related to SLPs was growth and learning. SLPs sought learning experiences related to telepractice and AAC to meet the challenges of providing services during COVID-19. One SLP (81) talked about using online resources more than she had before (e.g., instructional modules or webinars), saying “I got some really good training on that. … And anything that kind of makes you grow and stretch and step outside your comfort zone is good”. While completing these pieces of training contributed to SLPs’ growth and perceived effectiveness during the pandemic, some noted this added to the workload and overall level of stress. The increase in stress was captured for both parents and SLPs under emotional impact. For example, one SLP (40) said, “That was a huge challenge that I spent many, many hours those first few days teaching myself to be better [at telepractice]”. Some SLPs also reported feeling emotionally drained from worrying about more vulnerable children in their caseloads. One SLP (1) described:

The most difficult thing is parents that I don’t have a lot of communication with. It’s hard to— I worry about those kids, I worry about their parents, I worry if they’re okay… those kids keep me awake at night.

The emotional impact on families was complicated, with many experiencing negative and positive outcomes simultaneously. Participants talked about the increases in anxiety, stress, feeling overwhelmed and even guilt. One parent (28) spoke about the many roles she had to take on during the pandemic, saying “It was very stressful because I was the teacher, I was the speech-language pathologist, I was the activity— I was everything”. Another parent (53), who was both working full time at home and caring for her son, described feeling “pulled in a million directions”, “guilt-ridden” and “trapped”, saying, “It breaks my heart as his mom because I know that he needs something that I’m not able to give him right now”. Yet even with the emotional toll, participants also identified positive outcomes, including one parent (39) who called her experience “empowering”. Another parent (7) described positive emotions despite the difficulties of the pandemic, saying:

As negative as the pandemic has been…I can see the positives from it just because there’s a lot of things that I didn’t know that [my child] knew. And so, it’s been awesome seeing her use her device in ways that I didn’t know that she knew how…It makes me excited for the future to know that there is more that she can be doing, and I want to push towards her doing better and getting better with it than what she ever has been.

Another output factor related to both the SLPs and parents was seeing the other side. Parents and SLPs discussed the ways that service delivery during the pandemic brought the worlds of home and therapy closer together. This change meant they were able to gain insight into the relationship and interactions the child had with the other person. Both a product of and a mechanism for change, “seeing the other side” meant that parents learned more about what SLPs were doing, and SLPs learned more about what parents were doing. This was described as impacting parents and SLPs positively by shifting mindsets and equipping them to work better together. One parent (5) remarked, “I feel like that’s kind of opened doors for me to be able to like I said, see more of what she does, ask more questions one-on-one and get a direct answer”. Another parent (45) said, “I do feel like there’s more collaboration, I guess, more understanding on my part what they’re having her do at school. And I think seeing what she’s doing helps me trust the team more”. SLP 1 explained:

Parents being able to see what I do kind of demystifies it a little bit, I think. Unfortunately, the district is not super supportive of parents observing sessions during normal circumstances. So, it’s been really nice to have parents there more see what I do, see that it’s things they can do that— I’m not a magician.

Similarly, it was helpful for SLPs to see the home environment. One SLP (12) said, “It’s nice to see and communicate more about what’s been going on at home because, I mean, that’s the only environment the kids are in now. So that’s new information”.

At all levels (child, family, SLP), these outputs were seen to cycle back as inputs within the larger system, forming a complex chain of factors reinforced either positively or negatively through a feedback loop. For some, this cycle was seen to have a positive broader impact, making it so that parents and SLPs saw even greater gains in children’s communication than they had before the pandemic. For many others, however, the sequence of reciprocal causes and effects meant that these factors ultimately intensified and aggravated one another, leading to a worsening of the situation for children, families and service providers; thus, the system factors with the CIPO framework had explanatory power in understanding the potential influences on the disparities that were described in the broader impact for children.

Discussion

This study used semi-structured interviews and qualitative methods to reveal parent and SLP perspectives on context-, input-, process- and output-related factors that determined broader impacts of AAC service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic on children, families and SLPs. Although unique characteristics of children, families and SLPs appeared to play a role, it was process-related factors associated with (a) the nature of service provision, and (b) family-service provider partnerships that seemed to play the strongest roles in shaping impact. Furthermore, these processes produced short-term outputs for children, their families and their service providers that played cyclical roles in shaping longer-term or broader impacts (e.g., changes in communication and behavior, seeing the other side, the emotional impact for families and SLPs).

This system of impact seems to explain the variability and disparities that were evident and that echoed both prior literature that has identified inherent challenges with remote learning for children in low-income families (Colvin et al., Citation2022), and other emerging research about how the pandemic has deepened and widened preexisting inequities for children in the US (Slavin & Storey, Citation2020). When input- and process-related factors combined to lead to positive short-term changes, these positive outcomes returned to the systems as inputs and led to even more positive outcomes. These findings replicate those found prior to the pandemic, which suggests there are numerous potential benefits to telepractice (Casale et al., Citation2017). During the pandemic, similar positive benefits were found when input- and process-related factors aligned in supportive ways. For example, when SLPs could spend time in children’s natural environments via telepractice to parent-coached intervention, positive gains from the child were also reported. When stakeholders started from a place of disadvantage (e.g., families with fewer supports, greater demands; SLPs with fewer supports; children who received fewer and lower-quality services during the pandemic), they were often more likely to experience negative short-term outcomes (e.g., increases in challenging behaviors, parent stress), which then cycled back as inputs. These inequities place urgency on understanding how to intervene to stop widening disparities and improve access to critically needed services for all children who use AAC and their families.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided a unique opportunity for service providers such as SLPs to observe and better understand children in their home environments. Even though SLPs in the current study were typically delivering telepractice services for the first time, many reported they found it more successful than expected, particularly when they engaged in the use of technology that fit family preferences, and offered consultation and coaching alongside direct services – both of which are known to be effective strategies for providing telepractice prior to the pandemic (Camden & Silva, Citation2020). Telepractice within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic provided many SLPs and parents with a lens through which to see the other stakeholder’s perspectives, which was credited with contributing to positive outcomes that occurred. This finding extends prior research of Camden and Silva, who reported similar perspectives from physical therapists and occupational therapists regarding the benefits of “seeing into” the client’s home for the first time. With this finding comes an emphasis on the importance of family-service provider partnerships, as well as questions about how SLPs and parents can develop trusting relationships when they may have different views, goals and prior experiences. During discussions of the current findings, the research team was reminded of Allport’s (Citation1954) theoretical work on intergroup contact, which proposed that interaction between members of different groups would lead to increased trust and understanding when members of the two groups face a shared challenge with equal-status power and common goals. Looking to the post-pandemic future, these ideas raise questions about how a narrative of shared challenges with common goals and equal-status partnerships between parents and service providers could benefit children with complex communication needs and their families.

Implications

The COVID-19 pandemic has necessitated in-the-moment problem-solving and changes to routines and priorities; the current study highlights the strength and resilience of children with AAC needs, their families and their service providers. Although there is a need to reduce inequities and improve support for all children who use AAC during the pandemic and beyond, we recommend taking a strengths-based approach to solving the evolving needs of families and children who receive services and the service providers who deliver them. This type of approach builds on the capabilities of each of these stakeholders by capitalizing on preexisting skills, experiences and resources.

At the policy level, the findings suggest that strategies are needed to disrupt widening disparities. Effective education and healthcare policies could eliminate or reduce barriers such as lack of access to communication services, AAC systems and technology for telepractice (e.g., consistent internet access). Policies are also needed to provide direct support for overburdened families caring for their children; this will be especially important to families that have lost in-person care support usually provided at the school level.

The findings also have implications for stakeholders who train and educate preservice and practicing service providers. SLP supports were an important input factor contributing to the impact of this study, and service providers working with children who require AAC may need and want training and support related to both telepractice and AAC more generally (Biggs, Rossi, et al., Citation2022). Useful support may focus on how SLPs and other service providers can implement evidence-based AAC practices, build strong partnerships with families, and provide effective services via telepractice.

Finally, there are clinical and educational implications for SLPs. Parents reflected positively on the new ability to see and participate more in their child’s therapy session, and SLPs reflected positively on the opportunity to see into the child’s natural environment. Moving forward, both during and beyond the pandemic, SLPs should consider ways of being more transparent about what happens at school or in the clinic (e.g., providing an opportunity for a family to videoconference into a session during the school day, sending a recorded video of their child working with the SLP). In addition, SLPs should ensure that they elicit information about the home environment and interactions between the child and other family members to inform intervention goals and strategies. Innovative ways to deliver services that include sessions conducted via telepractice should be considered beyond the pandemic to provide maximum support to families and children in their home settings and potentially strengthen SLP-family partnerships for service delivery.

Limitations and future directions

It is important to note that the findings (a) reflect primarily the experiences of children and families who were receiving services, (b) portray the experiences of parents and SLPs in the US, (c) capture perspectives at one point in time and (d) discuss perceptions of impact and not measurable changes in children’s skills.

The decision to conduct interviews via Zoom was a practical one. At the time of the study, very little was known about COVID-19 or how to limit its spread. In-person research was not considered safe, and face-to-face research with human subjects was prohibited by many research ethics boards. Conducting interviews via Zoom allowed us to reach participants across the US but also likely limited participation from SLPs and parents in both rural and urban settings who may have had limited access to technology and/or telepractice experience, possibly explaining why the majority of participants (56% of parents and 52% of SLPs) described their location as suburban. Parents and SLPs without internet access or access to computers are likely to be the same individuals who were most negatively impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic and the resulting changes in service delivery. As a result, the impacts of COVID described in this research are unlikely to generalize to populations that are not able to access the technology support needed for teletherapy. Concern about the lack of contact with these families is reflected in many of the SLP interviews, and future research should explicitly target families and children who were lost in the transition to telepractice to identify ways to better support them during and beyond the pandemic.

Other limitations include that most participants were female. This was expected for SLPs, given that 96% of SLPs in the US are female (American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, Citation2019); however, the parents interviewed were also primarily female (n = 1 male), which means that parent perspectives are mostly those of mothers. Additionally, of the parents interviewed, 76% (n = 19) were employed outside the home, which may partly explain why they reported feeling overwhelmed with trying to “do it all”.

This study focused exclusively on the experiences of parents and SLPs in the United States of America. Although these findings may not generalize across the globe, this decision was a purposeful one. Recognizing that pre-pandemic service-delivery models were inherently different across the world and that governments made different decisions related to school and business operations during COVID-19, limiting recruitment to one country felt necessary to better understand the experiences of parents and SLPs within one particular context.

Finally, this study captures the perceptions of parents and SLPs on the impact of the pandemic during a small window of time, from July to August 2020. As this pandemic continues across the world, continued research is needed to document the impact of COVID-19 and rapidly changing policies on SLPs, families and children over time. Future research should also quantitatively investigate the impact of the pandemic on SLPs, families and children who use AAC to supplement the findings of the current study and provide a more complete picture.

Conclusion

This research contributes critical insight into the experiences of families and SLPs who receive and deliver AAC services during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. Although a number of questions for future research are raised, the findings offer explanations for widening disparities and suggest the need for urgency in identifying support to alleviate pandemic-related challenges for families and children. Findings also highlight the critical role of access to quality AAC services and family-service provider partnerships, underscoring the importance of further research, advocacy and practice in these areas during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

2020-0040_Supplemental_for_T_F_Oct_8.docx

Download MS Word (19.6 KB)Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the efforts of Brianna Coltellino, Erica Emery and Abbie Allen in data collection and analysis for this project. The authors also thank the parents and SLPs who graciously shared their experiences with us.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Chromebook is a trademark of Google LLC, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 04043, U.S.A.

References

- Aishworiya, R., & Kang, Y. Q. (2021). Including children with developmental disabilities in the equation during this COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(6), 2155–2158. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04670-6

- Akemoglu, Y., Muharib, R., & Meadan, H. (2020). A systematic and quality review of parent implemented language and communication interventions conducted via telepractice. Journal of Behavioral Education, 29(2), 282–316. doi:10.1007/s10864-019-09356-3

- Allport, G. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Addison-Wesley.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2019). A demographic snapshot of SLPs. The ASHA Leader, 24, 32–32. doi:10.1044/leader.AAG.24072019.32

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2020). COVID-19 Tracker Survey, May 2020. https://www.asha.org/Research/memberdata/COVID-19-Tracker-Survey/

- Ando, H., Cousins, R., & Young, C. (2014). Achieving saturation in thematic analysis: Development and refinement of a codebook. Comprehensive Psychology, 3, 1–7. doi:10.2466/03.CP.3.4

- Beukelman, D. R., & Light, J. C. (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (5th ed.). Paul H. Brookes Publishing Co.

- Biggs, E. E., Rossi, E. B., Douglas, S. N., Therrien, M. C. S., & Snodgrass, M. R. (2022). Preparedness, training, and support for augmentative and alternative communication telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 53(2), 335–359. doi:10.1044/2021_LSHSS-21-00159

- Biggs, E. E., Therrien, M. C. S., Douglas, S. N., & Snodgrass, M. R. (2022). Augmentative and alternative communication telepractice during the COVID-19 pandemic: A national survey of speech-language pathologists. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 31(1), 303–321. doi:10.1044/2021_AJSLP-21-00036

- Brady, N. C., Bruce, S., Goldman, A., Erickson, K., Mineo, B., Ogletree, B. T., Paul, D., Romski, M. A., Sevcik, R., Siegel, E., Schoonover, J., Snell, M., Sylvester, L., & Wilkinson, K. (2016). Communication services and supports for individuals with severe disabilities: Guidance for assessment and intervention. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 121(2), 121–138. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-121.2.121

- Camden, C., & Silva, M. (2020). Pediatric telehealth: Opportunities created by the COVID-19 and suggestions to sustain its use to support families of children with disabilities. Physical and Occupational Therapy in Pediatrics. Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/01943638.2020.1825032

- Casale, E. G., Stainbrook, J. A., Staubitz, J. E., Weitlauf, A. S., & Juarez, A. P. (2017). The promise of telepractice to address functional and behavioral needs of persons with autism spectrum disorder. International Review of Research in Developmental Disabilities, 53, 235–295. doi:10.1016/bs.irrdd.2017.08.002

- Colvin, M. K., Reesman, J., & Glen, T. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 related educational disruption on children and adolescents: An interim data summary and commentary on ten considerations for neuropsychological practice. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(1), 45–71. doi:10.1080/13854046.2021.1970230

- Constantino, J. N., Sahin, M., Piven, J., Rodgers, R., & Tschida, J. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities: Clinical and scientific priorities. American Journal of Psychiatry, 177(11), 1091–1093. Advance online publication. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060780

- Daks, J. S., Peltz, J. S., & Rogge, R. D. (2020). Psychological flexibility and inflexibility as sources of resiliency and risk during a pandemic: Modeling the cascade of COVID-19 stress on family systems with a contextual behavioral science lens. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.003

- Fong, R., Tsai, C. F., & Yiu, O. Y. (2021). The implementation of telepractice in speech language pathology in Hong Kong during the COVID-19 pandemic. Telemedicine and e-Health, 27(1), 30–38. doi:10.1089/tmj.2020.0223

- Fontanesi, L., Marchetti, D., Mazza, C., Di Giandomenico, S., Roma, P., & Verrocchio, M. C. (2020). The effect of the COVID-19 lockdown on parents: A call to adopt urgent measures. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 12(S1), S79–S81. doi:10.1037/tra0000672

- Goldbart, J., & Marshall, J. (2004). “Pushes and pulls” on the parents of children who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20(4), 194–208. doi:10.1080/07434610400010960

- Granlund, M., Björck-Åkesson, E., Wilder, J., & Ylvén, R. (2008). AAC interventions for children in a family environment: Implementing evidence in practice. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 24(3), 207–219. doi:10.1080/08990220802387935

- Guest, G., Bunce, A., & Johnson, L. (2006). How many interviews are enough?: An experiment with data saturation and variability. Field Methods, 18(1), 59–82. doi:10.1177/1525822X05279903

- Jeste, S., Hyde, C., Distefano, C., Halladay, A., Ray, S., Porath, M., Wilson, R. B., & Thurm, A. (2020). Changes in access to educational and healthcare services for individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities during COVID-19 restrictions. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(11), 825–833. doi:10.111/jir.12776

- John Hopkins University of Medicine. (2020). Coronavirus Resource Center. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/

- Mandak, K., & Light, J. (2018). Family-centered services for children with ASD and limited speech: The experiences of parents and speech-language pathologists. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 48(4), 1311–1324. doi:10.1007/s10803-017-3241-y

- Masonbrink, A. R., & Hurley, E. (2020). Advocating for children during the COVID-19 school closures. Pediatrics, 146(3), e20201440. doi:10.1542/peds.2020-1440

- Miller, C. (2020, July 16). In the same towns, private schools are reopening while public schools are not. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/07/16/upshot/coronavirus-school-reopening-private-public-gap.html

- Neece, C. L., Green, S. A., & Baker, B. L. (2012). Parenting stress and child behavior problems: A transactional relationship over time. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 117(1), 48–66. doi:10.1352/1944-7558-117.1.48

- Neece, C., McIntyre, L. L., & Fenning, R. (2020). Examining the impact of COVID-19 in ethnically diverse families with young children with intellectual and developmental disabilities. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 64(10), 739–749.

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Pavičić Dokoza, K. (2020). Telepractice as a reaction to the COVID-19 crisis: Insights from Croatian SLP settings. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 12(2), 93–104. doi:10.5195/ijt.2020.6325

- Provenzi, L., Grumi, S., & Borgatti, R. (2020). Alone with the kids: Tele-medicine for children with special healthcare needs during COVID-19 emergency. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2193. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02.193

- Reilly, S., Harper, M., & Goldfeld, S. (2016). The demand for speech pathology services for children: Do we need more or just different? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 52(12), 1057–1061. doi:10.1111/jpc.13318

- Saldaña, J. (2021). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (4th ed.). Sage Publications.

- Sandelowski, M. (2000). Whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in Nursing & Health, 23(4), 334–340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:4%3C334::AID-NUR9%3E3.0.CO;2-G

- Sandelowski, M. (2010). What’s in a name? Qualitative description revisited. Research in Nursing & Health, 33(1), 77–84. doi:http://doi.org/10.1002/nur.20362

- Scheerens, J. (1990). School effectiveness research and the development of process indicators of school functioning. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 1(1), 61–80. doi:10.1080/0924345900010106

- Simacek, J., Dimian, A. F., & McComas, J. J. (2017). Communication intervention for young children with severe neurodevelopmental disabilities via telehealth. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 47(3), 744–767. doi:10.1007/s10803-016-3006z

- Slavin, R. E., & Storey, N. (2020). The US educational response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Best Evidence of Chinese Education, 5(2), 617–633. doi:10.15354/bece.20.or027

- Smith, A. C., Thomas, E., Snoswell, C. L., Haydon, H., Mehrotra, A., Clemensen, J., & Caffery, L. J. (2020). Telehealth for global emergencies: Implications for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 26(5), 309–313. doi:10.1177/1357633X20916567

- Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Biller, M. F., Appel, K. E., Meadan, H., & Halle, J. W. (2017). Telepractice in speech–language therapy: The use of online technologies for parent training and coaching. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 38(4), 242–254. doi:10.1177/1525740116680424

- Tucker, J. K. (2012). Perspectives of speech-language pathologists on the use of telepractice in schools: Quantitative survey results. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 4(2), 61–72. doi:10.5195/IJT.2012.6100

- White, L. C., Law, J. K., Daniels, A. M., Toroney, J., Vernoia, B., Xiao, S., Feliciano, P., & Chung, W. K. (2021). Brief report: Impact of COVID-19 on individuals with ASD and their caregivers: A perspective from the SPARK cohort. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 51(10), 3766–3773. doi:10.1007/s10803-020-04816-6

- Woodman, A. C., Mawdsley, H. P., & Hauser-Cram, P. (2015). Parenting stress and child behavior problems within families of children with developmental disabilities: Transactional relations across 15 years. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 36, 264–276. doi:10.1016/j.ridd.2014.10.011