Abstract

This study’s goal was to inform the selection of the most frequently used words to serve as a reference for core vocabulary selection for Hebrew-speaking children who require AAC. The paper describes the vocabulary used by 12 Hebrew-speaking preschool children with typical development in two different conditions: peer talk, and peer talk with adult mediation. Language samples were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analyzed using the CHILDES (Child Language Data Exchange System) tools to identify the most frequently used words. The top 200 lexemes (all variations of a single word) in the peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk conditions accounted for 87.15% (n = 5008 tokens) and 86.4% (n = 5331 tokens) of the total tokens produced in each language sample (n = 5746, n = 6168), respectively. A substantially overlapping vocabulary of 337 lexemes accounted for up to 87% (n = 10411) of the tokens produced in the composite list (n = 11914). The results indicate that a relatively small set of words represent a large proportion of the words used by the preschoolers across two different conditions. General versus language-specific implications for core vocabulary selection for children in need of AAC devices are discussed.

Frequency of word usage by Hebrew preschoolers: implications for AAC core vocabulary

Individuals who require augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) who are not literate may comprehend language via the auditory channel but are expected to produce language using unaided AAC (e.g., facial expressions, gestures) or aided AAC (e.g., graphic symbols on communication boards; Loncke, Citation2020; Smith, Citation2015). This asymmetrical input/output poses challenges for AAC system vocabulary selection (Savaldi-Harussi & Fostick, Citation2021; Trembath et al., Citation2007). While children with typical development can access lexicons of thousands of words (Clark, Citation1993), their peers who require AAC primarily access vocabulary selected by others. To better cope with AAC system limitations and facilitate access to frequently used words, AAC systems must be organized efficiently and include both personal and core vocabularies (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020) that enable functional communication (e.g., requests, comments, rejections) and language development in line with peers with typical development (van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012).

Core vocabulary lists include a range of up to 200-400 words used consistently across environments and communication partners and may account for approximately 80% of the total vocabulary in spoken language. Core words lists include both function words (e.g., pronouns, conjunctions, prepositions, determiners, interjections) that provide grammatical information and establish relationships between words, as well as content words (e.g., verbs, nouns, adjectives, adverbs) that convey lexical meaning (Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012). Some authors suggest that core vocabulary is particularly useful for vocabulary selection for AAC systems (Sanders & Blakeley, Citation2021; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012) because it is a relatively small set of words that can be made accessible on AAC systems and can be taught across classroom settings, topics, and activities, laying a strong foundation for language development (Erickson et al., Citation2021; van Tatenhove, Citation2009; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012). Additionally, instant access to frequently used words across settings reduces needed cognitive and motor effort (Hill et al., Citation2014; Marvin et al., Citation1994; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016), and inclusion of function words enables the generation of grammatically correct structures; thus supporting language growth by encouraging use of various linguistic categories (e.g., “that”, “it”, “the”, “a”, “can”; Beukelman & Light, Citation2020).

Another vocabulary selection approach emphasizes the use of content and personalized words for beginning communicators with complex communication needs (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020; Laubscher & Light, Citation2020). Some of these words are part of the core vocabulary (e.g., “go”, “want,” “mom”), while others relate to specific circumstances and are classified as fringe or extended vocabulary (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). While based on the idea that children’s early vocabulary primarily consists of nouns (e.g., people, animals, objects) as found in parental reports and language sample studies (Dromi, Citation1987, Laubscher & Light, Citation2020), vocabulary for nonliterate individuals who use AAC is often chosen from a functional, rather than developmental, perspective (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). Concrete nouns are considered easiest to teach and have functional value for the communicator (Adamson & Boreham, Citation1974); however, vocabulary for preliterate individuals who use AAC should include both essential messages and vocabulary required for language development (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). As such, professionals selecting vocabulary for individuals who use AAC face a challenge: optimizing communication by using a limited number of words while still best representing linguistic morpho-syntactic features to support language growth (Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015; Laubscher & Light, Citation2020; Liu & Sloane, Citation2006; Marvin et al., Citation1994; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012).

Tools developed to help decide which words to prioritize in vocabulary selection and instruction include: (a) environmental or ecological inventories of vocabulary relevant to particular settings (e.g., bedtime, mealtime); (b) communication checklists (e.g., MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory: Words and Sentences; Fenson, Citation2007); (c) developmental vocabularies of age-appropriate words across semantic categories (e.g., substantive words [things, people], generic verbs [e.g., “make”, “give”], relational words [e.g., “big,” “little:”], affirmation/negation [e.g., yes, no], recurrence/discontinuation [e.g., more, all gone]; (Banajee et al., Citation2003; Lahey & Bloom, Citation1977; Laubscher & Light, Citation2020; Morrow et al., Citation1993); and (d) core vocabulary, which is the focus of the current study.

Research has sought to identify core words for different populations and various contexts. Primarily this has involved recording participants in spontaneous or structured discourse, followed by transcription and statistical analysis to calculate word usage frequencies (Beukelman et al., Citation1989; Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016). Core word usage has been studied for Afrikaans (Hattingh & Tönsing, Citation2020), Zulu (Mngomezulu et al., Citation2019), Korean (Shin & Hill, Citation2016), Spanish (Soto & Cooper, Citation2021), Sepedi (Mothapo et al., Citation2021), and, most represented in the literature, English (van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016). English core vocabularies have been studied among toddlers (Banajee et al., Citation2003), preschool children (Beukelman et al., Citation1989; Marvin et al., Citation1994), school-aged children (Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015), adults at mealtimes (Balandin & Iacono, Citation1999), and elderly people during free discourse (Stuart et al., Citation1997).

Banajee et al. (Citation2003) investigated the core vocabulary of 50 typically developing toddlers in preschool settings. All 50 children used the same nine words (e.g., “I”, “no”, “yes/yeah”, “want”, “it”, “that”, “my”, “you”, “more”) serving many pragmatic functions such as requesting, affirming, and negating. Other frequently used words were “go”, “who”, “some”, “help”, “mine”, “the”, “is”, “on”, “in”, “here”, “out”, “off”, and “all done/finished.” Similarly, analyzing language samples of six preschoolers, Beukelman et al. (Citation1989) found the top 25 most frequently used words accounted for 45.1% of the total word sample, the top 50 words accounted for 60%, and the top 250 words accounted for 80% of the total word sample. Frequently occurring words were verbs (e.g.,” want”, “eat”, “go”), demonstratives, prepositions, and adverbs; nouns were absent from the top core words reported. Boenisch and Soto (Citation2015) also provided core vocabulary analysis of 30 typically developing school-aged children attending second, fourth, sixth, and eighth grades. Of these children, 22 were English speakers and eight spoke English as a second language (ESL) based on samples collected during two consecutive school setting activities. Like preschoolers and toddlers, a relatively small core vocabulary was found, representing a large proportion of words used (e.g., the top 100 most frequently used words by the 22 English native speakers accounted for 71% of the total vocabulary while the top 200 words accounted for 80%). The verb “to be” (including all its grammatical variations) was the most frequently used and the second most frequently used word was “I.” Lexical category distribution showed that the percentage of function words (i.e., pronouns, conjunctions, prepositions) decreased as the top 100 most frequently used words expanded to the top 300, while content words (i.e., nouns, adjectives, verbs) increased as more words were included. For instance, the use of nouns increased from 7% in the top 100 words to 20% in the top 300 words. Notably, Boenisch and Soto counted all variations of a word as a single word; this singular default form is referred to as a lexeme in this study.

A significant increase in the use of AAC systems in Israel since 2015 (due to laws expanding device funding) has necessitated better guidelines to select and organize vocabulary for low- or high-tech AAC systems in Hebrew, the official national language of Israel with Arabic as a language with a special status. To date, this process has not yet been supported by systematic, evidence-based research. It remains based on the experience and educated guesswork of speech-language pathologists (SLPs) working with those who use AAC, developmental word lists from parental questionnaires (e.g., the Hebrew Communicative Developmental Inventory [HCDI], the Hebrew adaptation of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventories [MCDI]; Gendler-Shalev & Dromi, Citation2022; Maital et al., Citation2000), activity-based words, and English core vocabulary translations (Shacham, Citation2015). Moreover, studies of early morphological acquisition and early lexicon development of Hebrew-speaking children with typical development using language samples have primarily focused on specific lexical categories like verbs (Ashkenazi et al., Citation2016; Levie et al., Citation2020; Uziel-Karl, Citation2001), adjectives (Ravid et al., Citation2016), nouns (Ravid, Citation2006), and prepositions (Salmon, Citation2020), rather than comprehensive quantitative accounts more useful to AAC system implementation. An evidence-based core vocabulary would provide Hebrew-speaking individuals using AAC easier access to the most frequently used lexical categories essential for constructing messages most closely resembling spoken Hebrew, and an inventory from which AAC professionals could select appropriate vocabulary for Hebrew-speaking children with AAC needs.

Among additional considerations for vocabulary selection are the linguistic features of Hebrew, a Semitic language with a rich morphological system. All Hebrew verbs and certain nouns and adjectives are formed by integrating a consonantal root into a vocalic (vowel) pattern (e.g., r-q-d + CaCaC → raqad dance.M.3SG.PAST)Footnote1. The Hebrew verb system consists of five active and two passive patterns (denoted by P1, P2, etc.), the most frequent and productive of which is the P1 CaCaC pattern that often denote activity or accomplishment (Berman, Citation1993). Noun derivation is diverse and includes the root + pattern strategy, and a wealth of other means (e.g., affixation: raʕash + an → raʕashan [“rattle”], diminutives: sefer + on → sifron book.DIM [“little book”], deverbal nouns: n-s-ʕ from linsoʕa [“to travel”] → nesiʕa [“trip”], participles functioning as nouns: xole [“patient”]). Adjective derivation further includes affixation, zero conversion (e.g., the use of present participles as adjectives: xole [“sick”]) and reduplication (i.e., repetition of the final syllable: ʕagalgal [“roundish”].

Hebrew verbs (including grammatical verbs like haya [“was”] are inflected for number, gender, person, and tense (present, past, future; Berman, Citation1985). Additionally, verbs may take inflection for mood, e.g., imperative (e.g., shev sit.M.2SG.IMP [“sit!”]) or infinitive (e.g., lashevet sit.INF [“to sit”]). A complete Hebrew verbal paradigm has over 30 inflectional forms. Within sentences, Hebrew verbs agree with their subject noun in number, gender, and person. Nouns (and numerals, construct state) are marked for gender (M, F) and number (SG, PL, DU). The dual affix -ayim marks a pair (e.g., yad-ayim hand-two [“two hands”]). Nouns also alternate between free forms (e.g., yeled [“boy”]) and bound forms used before possessive suffixes (e.g., yald-i child-mine [“my child”]) or as the head of noun compounds (yald-ey gan children of kindergarten [“kindergarten children”]). Adjectives and demonstratives are inflected for number and gender. They agree with their head nouns in number, gender, and definiteness (e.g., ze yeled gadol this boy big.M.SG [“this is a big boy”] vs. zot yalda gdola this girl big.F.SG [“this is a big girl”] vs. ha-yelad-ot ha-gdol-ot ha-ele the-girls the big.F.PL these [“these big girls”]). Finally, pronouns take a free form only as subjects (e.g., ani [“I”], ata [“you”] M.SG, hu [“he”], anaxnu [“we”]). In all other contexts they are suffixed to prepositions, (e.g., shel + ata [“of you”] = shel-xa [“your/yours”]. The possessive particle (shel [“of”]) and existential particles (yesh [“there is”] and eyn [“there isn’t”]) are also inflected for number, gender, and person (e.g., eyneni [“I not exist/not present”] 1SG, eynxem [“you not exist/not present”] M.2PL (but the latter forms are archaic and are rarely used in everyday language).

Non-inflecting categories include personal pronouns, articles and determiners, adverbs, quantifiers, connectors (conjunctions), complementizers, modal adverbs (e.g., asur [“forbidden”], mutar [“allowed”]), question words, negation/assertion words, nouns denoting proper names and places, days/months, and social words (e.g., discourse markers, formulaic greetings, interjections). Additionally, unlike English, Hebrew marks only the definite article (ha-) and has an overt accusative marker (et).

For a morphologically rich language, one critical question about representing Hebrew vocabulary on AAC systems is whether a single communication symbol should represent a word with its affixes or whether stems should be represented separately from their inflectional or derivational forms. This study posited that the layout of the Hebrew communication systems should include both an inventory of the most frequently used words in their fully inflected form for easy access and motor effort along with a set of lexemes (a default word representing a paradigm of inflected forms) which provide navigation options for more inflectional forms. Therefore, the goal of this study is to identify the list of the most frequent Hebrew lexemes and their various grammatical forms that accounted for approximately 80% of the total vocabulary used by preschoolers with typical development. The resulting list may serve as a reference for core vocabulary selection for Hebrew-speaking children who require AAC.

It was hypothesized that the Hebrew word list identified in this study would resemble the English core vocabulary list in overall lexicon size and category distribution (Beukelman et al., Citation1989; Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015). The following research questions were posed about the language samples from Hebrew-speaking children with typical development:

What are the most frequently used word lists in the language samples of a group of young children with typical development and what portion of the entire sample do they comprise?

What is the lexical category coverage in the language samples of a group of young children with typical development?

Which lexemes overlap when comparing the samples obtained by the two different elicitation conditions and what portion of the entire sample do they comprise?

Method

Research design

An accepted psycholinguistic method (Uziel-Karl & Berman, Citation2000) and quantitative descriptive observational design (Mngomezulu et al., Citation2019) were used to capture the participants’ natural speech during two peer-talk conditions. Each of the four triads was initially randomly assigned to the peer talk or adult-mediated peer talk condition. After completing the first session in one of the conditions, each triad moved to another quiet room to complete the second part of the study in the second condition. The children had a short break between sessions.

All required ethical approvals were obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at the first author’s university (protocol number AU-HEA-GH-20190130-2). Furthermore, parents were informed of all study aspects via an information letter; and signed a written consent form for their children’s participation in the study. The children were also provided with verbal information on all aspects of the study. Only children who agreed to participate were included in the study.

Participants

Participants in this study were 12 children, six boys and six girls, aged 3;8–5;8 (years/months) (M = 4;8, SD = 0.7). All of the children lived in the same community, attended the same preschool, and knew each other. They were recruited from among acquaintances and personal contacts of the research team. They were native Hebrew speakers with typical sensory, neurological, linguistic, and communicative development. Based on parent reports, all of the participants were verbally and socially active; namely, all of the children were reported to engage in social activities (Beukelman et al., Citation1989). All parents provided signed informed consent for the participation of their children in the research.

Materials

The room was equipped with age-appropriate toys for each condition. For the peer talk condition, toys and games included a puzzle of Bob the BuilderFootnote2, PlaymobilFootnote3 items (e.g., aircraft, medical truck), a ball, a box with toy animals, and a box with kitchen items. For the adult-mediated peer talk condition, two construction games were used, designed for building replicas of models presented on cards. The experimental sessions were recorded using a Philips DVT1150Footnote4 audio recorder placed in a central location in the room.

Researchers

Six research assistants carried out the study. All were third-year speech-language pathology students in the Department of Communication Disorders at the first author’s university. Each assistant was trained by the first author and had hands-on experience interacting and working with young children. The six team members carried out the procedures (meditating sessions, recording, transcribing, and data coding) under the supervision of the first author.

Setting

Recordings took place at the home of a research assistant who lived in the same community as the children. The 12 children were randomly divided into four triads prior to the elicitation of the experimental task (Triad 1: two boys and one girl; Triad 2: three boys; Triad 3: three girls; Triad 4: two girls and one boy). Peer triadic interaction was preferred over a larger group of children because it reflects naturally occurring interaction among children of the same age in which each participant has the opportunity to take an active role, initiate questions, answer questions; and thus reflects the child’s evolving linguistic abilities as expressed in daily communication (Blum-Kulka & Dvir-Gvirsman, Citation2010; Salmon, Citation2020).

Studies have reported that the elicitation method affects children’s production. For example, Evans and Craig (Citation1992) reported that in an interview setting, children produced more complex linguistic structures than in free play, and their vocabulary diversity was greater in the former setting; thus, two different elicitation methods were selected for the current study: (a) peer talk, which aimed to capture naturally occurring conversation during a free play session without adult intervention; and (b) peer talk with adult mediation, in which an adult used a set of prompts to elicit conversation between the children. These specific settings were used to elicit spontaneous speech samples representative of the distribution of various structures in natural spoken language (Ford et al., Citation2008) and to strengthen the choice of the target core vocabulary by identifying overlapping words used during the two different elicitation methods.

Procedures

Each triad met with the research assistants in a quiet room for the two different interactive sessions (peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk). Sessions lasted an average of 40 min (range: 30–50). Each session was audio-recorded using a recording device placed in a central location in the room. During the peer talk condition, the participants were asked to behave as they would normally during playdate interactions. The research assistant served as an observer and did not interfere with the interaction.

During the adult-mediated peer talk condition, the research assistant introduced the construction activity and encouraged the children to interact with one another by saying Let’s see who can build this model. During the activity the research assistant asked the children five questions unrelated to the activity: (a) Tell me about your family, (b) Which games do you like to play at home? (c) What does your room look like? Describe your room to me, (d) Which movie do you like best? and (e) What is the movie bout? Despite the semi-structured interview format only the children’s output was analyzed.

Data collection and transcription

Processing of the audio-recorded interactive sessions was done using the tools of CHILDES (Child Language Data Exchange System) and involved the following steps: First, all recordings were transcribed verbatim by the six research assistants using the CHAT (Codes for the Human Analysis of Transcripts) system with adaptation to Hebrew (MacWhinney, Citation2000; Uziel-Karl, Citation2001). Homonyms were transcribed differently but consistently to differentiate them from each other. Unintelligible words were marked as such in the transcription (i.e., xxx) and were excluded from the analysis. The transcriptions of each condition were then grouped together into one sample; thus yielding two samples: one peer talk, and one adult-mediated peer talk.

Transcription Reliability

The research assistants who transcribed the recording were trained by the first and second authors on the conventions of the Hebrew broad phonemic transcription in CHILDES prior to the beginning of the project. An additional research assistant not part of the study independently transcribed a randomly selected portion of approximately 20% of each of the eight recordings. These transcription samples were compared to the corresponding excerpt of the original transcript. Following Hill et al. (Citation2014), the frequency of agreement was calculated: the ratio F(agree) between the total number of utterances and the total number of words (TNW) in each of the two transcription samples. These global measures were selected because they reflect the overall consistency of transcripts between raters. F(agree) was computed using the Equation: F(agree)% = (ΣF(min)/ΣF(max)) *100 where F(min) is the lowest reported value for TNW, or total number of utterances in the compared samples and F(max) is the highest reported value for TNW or total number of utterances. An inter-rater reliability of 90% is recommended (Hill et al., Citation2014). For the current study, the F(agree) pooled across eight transcripts was 93.8% for TNW and 82.4% for total number of utterances. The discrepancy in the number of utterances is thought to be related to transcribing a whole turn of a specific participant versus transcribing a turn based on utterance boundaries; nevertheless, this discrepancy does not affect the study results as the analysis focuses on word frequency, not grammatical analysis. Following Cucchiarini (Citation1996), word-by-word transcription agreement was established by calculating agreements on words that were identically transcribed, whereas disagreements were counted when a word was omitted, added, or not identically transcribed. Transcription agreements were calculated by the number of agreements divided by the number of agreements and disagreements, multiplied by 100. The percentage of agreement obtained in this study was 83%. There are no standardized criteria for acceptance percentages of transcription agreement. Cucchiarini notes that 75% is an acceptable criterion for word-by-word transcription agreement. As another reliability measure, two of the six research assistants who originally collected the data and transcribed the recordings rechecked all the words on the two word lists (peer talk, adult-mediated peer talk). They re-verified the level of consistency by translating each transcribed word into English and Hebrew; thus for words that had identical translations but were transcribed differently in error, a single unified form was selected based on transcription conventions. For example, according to the broad phonemic transcription conventions for this study, the word “bird” ציפור should have been transcribed as “cipor” but if it was mistakenly transcribed as “tsipor” the latter was eventually corrected to “cipor.”

Coding Reliability

The first author coded the words for their lexical categories on both lists (peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk). The second author then re-checked the coding. To resolve disagreements, a third psycholinguist was consulted. Coding was based on dictionary classification and Hebrew grammar books (Coffin & Bolozky, Citation2005; Glinert, Citation2017). To further ensure the reliability of the coding, the assigned lexical categories of the three-word lists were examined by an additional research assistant who was not part of the original project. Only 2% of the words were reclassified.

Data analysis

Frequency analyses

The frequency command (FREQ) in CLAN (Computer Language Analysis) was used to extract an exhaustive list of word forms with their frequencies in descending order separately for each of the two samples (peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk). A word form is defined as any given form of a word, either inflected or non-inflected. All word forms in a sample, including repetitions, were counted as tokens. Excel was then used to calculate the frequency (in percentages) of each word form out of the total number of words (tokens). For example, consider the following 10-word sample: “go”, “go”, “goes”, “gone”, “I”, “no”, “no”, “no”, “boy”, “boys”. This sample includes a total of 10 words (tokens). Applying the FREQ command to this sample yielded a list of seven different word forms with their respective frequencies: 3”no”, 2 “go”,1 “goes”, 1 “gone”,1 “I”, 1 “boy”, 1 “boys”. Using Excel, the coverage and frequency (in percentages), of each word form was calculated out of the total number of words (tokens) as follows: 3/10 “no” (30%), 2/10 “go” (20%), 1/10 “go” (10%), 1/10 “gone” (10%), 1/10 “I” (10%), 1/10 “boy” (10%), and 1/10 “boy” (10%). Then all inflected forms of a single lexeme (e.g., “go”, “goes”, “gone”; “boy”, “boys”) were grouped into one single lexeme (e.g., GO, BOY, respectively). This yielded a list of four lexemes and their coverage (percentages) out of the total number of words in the sample, as follows: 4/10 GO (40%), 3/10 NO (30%), 2/10 BOY (20%), and 1/10 I (10%). Moreover, this example shows that the most frequent word-form of the lexeme GO is “go” (20%).

Lexemes

As previously noted, words that had various grammatical variations were grouped into one single lexeme, whereas non-inflecting words were classified as lexemes a priori. Lexeme frequencies and their percentages were calculated separately for each condition and for the composite list yielding three-word lists: peer talk, adult-mediated peer talk, and the composite list. For each of the word lists, each lexeme was assigned a numerical value based on its frequency, such that the most frequently used lexeme was assigned the value 1. Then the cumulative percentages of the top 20, 50, 100, and 200 lexemes were calculated to identify the coverage of lexemes that accounted for approximately 80% of the total number of words produced in each word list.

Lexical categories, content, and function words

The words in each list were coded for their lexical categories and further divided into content and function words. The content words included verbs, adverbs, adjectives, nouns, modal verbs, and numbers; the function words included pronouns, question words, negations, exclamations, existentials, prepositions, conjunctions, quantifiers, and article-determiners.

Overlapping words

The two word lists, peer talk, and adult-mediated peer talk were compared to identify the vocabulary overlapping across the two samples. The identified overlapping lexemes and their frequencies were color-coded and unified into one list using Excel. The overlapping lexemes list was sorted by alphabetical order and their frequencies were recalculated, as well as their percentages out of the total words produced in the composite list (n = 11,419). Then this list was sorted by the frequency of the lexemes. Each lexeme was assigned a numerical value based on its frequency, such that the most frequently used lexeme was assigned the value 1. For reliability purposes, a research assistant not part of the original data collection team used Excel conditional formatting to compare and then extract the words that appeared on both lists.

Results

Description of the language sample and most frequently used words

describes the total number of tokens and lexemes in the two conditions and in the composite word list. A total of 11,914 tokens were produced by the 12 participants during the two conditions: peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk. Of the total 11,914 tokens, 5,746 tokens and 1,169 different word forms were produced during the adult-mediated peer talk condition and 6,168 tokens and 1,276 different word forms were produced during the peer talk condition. The different word forms were further analyzed and reduced to lexemes. A total of 634 lexemes accounted for the whole sample of tokens (n = 5,746) in the adult-mediated peer talk condition and a total of 639 lexemes accounted for the whole sample of tokens (n = 6,168) in the peer talk condition. The composite list contained a total of 936 different lexemes.

Table 1. Tokens, lexemes and top 20, 50, 100, and 200 most frequently used lexemes in the samples.

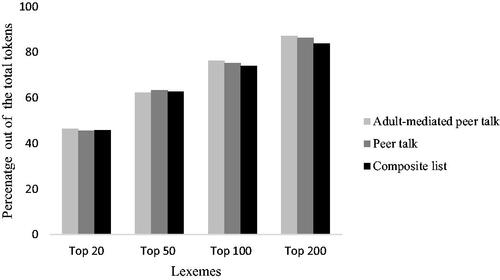

describes the occurrences and coverage of the top 20, 50, 100, and 200 most frequently used lexemes and their various grammatical forms across the three-word lists. For example, the top 20 lexemes occurred 2,671 times, accounting for 46.48% of the total number of tokens produced during the adult mediated condition. Similarly, the top 20 lexemes accounted for 45.67% and 45.74% of the total token number produced during peer talk and the composite list, respectively. The top 20, 50, 100, and 200 most frequently used lexemes accounted for similar percentages across the three word lists, in which the top 200 lexemes accounted for approximately 80% of the total number of tokens produced in each of the word lists, as illustrated in .

The list of the top 200 lexemes which accounted for 83.93% of the tokens (n = 9,999) produced in the composite list, along with their glosses, percentages, and lexical categories is presented in the , Supplemental material.

Coverage of lexical categories

The lexemes, including all their grammatical variations in each condition, were coded for their lexical categories. describes the distribution and coverage of lexical categories in the peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk conditions for top 200 (n = 5008, n = 5331) and 100 (n = 4,380, n = 4,641) lexemes.

Table 2. Coverage of lexical categories in the top 200 and top 100 lexemes across conditions.

Comparison of the lexical category distribution among the top 200 lexemes within each condition shows that six of the 16 lexical categories were used more frequently (higher percentage) during the adult-mediated peer talk condition than during the peer talk condition. For function words, the categories are compared as follows: prepositions: 13.56% versus 12.81%, conjunctions: 8.33% versus 6.51%, personal pronouns: 10.06% versus 7.86%, and existentials: 2% versus 1.56%. Regarding content words, nouns appeared more frequently: 11.78% versus 8.05% as did numbers: 3.21% versus 2.03%.

Ten other lexical categories were used more frequently during the peer talk condition. For functions words the categories were compared as follows: function words: demonstratives 7.77% versus 5.79%, negations: 5.63% versus 4.29% article-determiners: 5.85% versus 3.855, questions: 4.22% versus 2.98%, interjections: 2.76% versus 0.94% complementizers: 1.82% vs. 1.78%; and content words: proper names: 2.145 versus 1.82%, adverbs: 12.83% versus 11.58% and adjectives: 2.74% versus 2.62%.

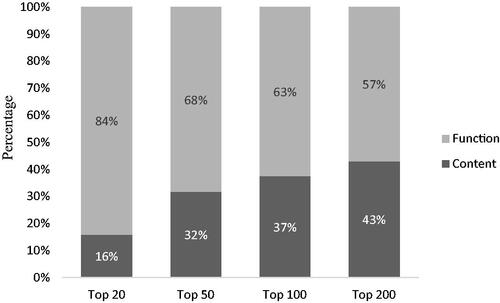

When comparing the coverage between function and content words among the top 20, 50, 100, and 200 most frequently used lexemes in the composite list, the coverage of content words increased as more words were included in the list. The percentages of content words in the top 20, 50, 100, and 200 most frequently used lexemes increased, respectively, as follows: 16%, 32%, 37% and 43%, and the percentages of function words decreased, respectively, as follows: 84%, 68%, 63% and 57%. This is evidence of an increase in the ratio of content to function words coverage when increasing from the top 20 to top 200 most frequently used lexemes, as shown in .

Overlapping words

When comparing the top 20 most frequently used lexemes by the Hebrew-speaking children in the two conditions, there was an overlap of 90% of the lexemes (n = 18) among the top 20. The 18 most frequently used lexemes in Hebrew in both conditions are listed in . These included the personal pronoun “I” (אני), an article-determiner “the” (ה׳ הידעה), conjunctions “and” (ו) and “also” (גם), complementizer “that” (ש), demonstrative pronouns “this” (זה), existential “there” “is/are” (יש), negation “no” (לא), accusative marker “et” (את), prepositions “in/in” “the” “be-/ba”- (בְּ/ּבָּּ), “to” + inflectional paradigm (ל-, לי, לו), “of” + inflectional paradigm (של), question word “what “(מה), and the verbs “want” (לרצות), “to be” (להיות), “to see” (לראות) and “to make” (לעשות).

Table 3. Top 18 lexemes overlapping both peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk conditions in the composite list’s 11,914 tokens.

The overlap analysis resulted in 337 lexemes that were common across the samples of the two conditions. These 337 overlapping lexemes accounted for 5,013 tokens (87.24%) of the adult-mediated condition and 5,402 tokens (87.58%) of the peer talk condition, as shown in . Moreover, these 337 lexemes accounted for 10,411 tokens (87.38%) in the composite list. The list of 337 overlapping lexemes in the composite list, including their rank, percentage, gloss, and lexical category, is presented in , Supplemental material.

Discussion

The present study proposed a method for determining a list of the most frequently used words that may serve as a reference for core vocabulary selection for Hebrew speakers who require AAC. Although there are different approaches to vocabulary selection for non-literate communicators who use AAC, all approaches appear to agree that the selected vocabulary should include both essential messages and vocabulary required for language development (Beukelman & Light, Citation2020). Moreover, following language interventions, the linguistic development of children who use AAC has been shown to follow patterns found in typical development (Savaldi-Harussi et al., Citation2019). This is the rationale for the use of a lexicon derived from typically developing children to serve as a reference for vocabulary selection for individuals who use AAC in the context of constructive teaching and learning practices related to vocabulary acquisition (Erickson et al., Citation2021, van Tatenhove, Citation2009).

Extracting a list of most frequently used words from the language samples of 12 preschool children with typical development across two conditions required a clear definition of what counted as a lexical element. Considering the characteristics of Hebrew (Berman, Citation1985), and the limited space of aided communication layouts (Loncke, Citation2020), all inflected forms of each word type were assigned a single default form or lexeme. Consequently, the word list of the most frequently used words for Hebrew suggested in this study consisted of lexemes (default forms) of inflecting lexical categories (nouns, verbs, adjectives, numbers, demonstrative pronouns, prepositions, and existentials) and non-inflecting lexical categories (personal pronouns, article-determiners, adverbs [including quantifiers], connectors [conjunctions], complementizers, question words, negation and assertion words, nouns denoting proper names, place names, days and months, and interjections [including social words]). Core words were defined as the most frequently used lexemes that account for approximately 80% of the total vocabulary in spoken language (van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012).

Core vocabulary coverage

As reported in other studies, the current study found that a small set of lexemes (default word forms) accounted for approximately 80% of the words used by typically developing Hebrew-speaking preschoolers, as found in the coverage of the top 200 lexemes and the 337 overlapping lexemes. Three wordlists were created in this study: Two word lists for the two conditions (peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk) and a composite list that resulted from combining the lists from the two conditions. The top 200 most frequently used lexemes in the composite list in this study accounted for 83.94% of the words used in the composite list, while the top 20, 50 and 100 accounted for 45.74%, 62.67% and 74% of the words used, respectively. Similar patterns were found for the word lists in each condition and were also observed in core vocabulary studies conducted in other languages, for example, French (Robillard et al., Citation2014), Afrikaans (Hattingh & Tönsing, Citation2020), Sepedi (Mothapo et al., Citation2021), and English. For English, Beukelman et al. (Citation1989) found that the top 25 most frequently used English words accounted for 45.1% of the total word sample and the top 50 words accounted for 60% among six preschoolers. Boenisch and Soto (Citation2015) also found that the top 100 most frequently used English words in the recorded sample accounted for 71.2% of the total vocabulary used by 22 native speakers and 74.8% of the total vocabulary used by eight students for whom English was a second language. The top 200 words accounted for 80.3% and 84.5% of the total vocabulary, respectively.

Coverage of lexical categories

The change observed between the top 20 most frequently used lexemes to the top 200 in the coverage of content and function words is supported by previous studies (Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015; Hattingh & Tönsing, Citation2020; Robillard et al., Citation2014). The coverage of function words was high (84%) among the top 20 most frequently used lexemes but decreased as the number of words increased in the sample list from the top 20 to the top 200 (57%). At the same time, the coverage of content words increased gradually from the top 20 (16%) to the top 200 (43%) most frequently used lexemes. This observed pattern is due to the fact that function words belong to closed word class and, consequently, there is a limited amount of them.

A comparison of lexical category distribution between the two conditions in this study revealed that some lexical categories were used more frequently in the adult-mediated elicitation method than in the peer talk condition, and vice versa. For example, prepositions, conjunctions, personal pronouns, existentials, nouns, and numbers were used more frequently in the adult-mediated condition while demonstratives, negation, article-determiners, question words, and interjections were used more frequently during peer talk. This finding might be attributed to the different elicitation methods; the adult-mediated elicitation method (interview) has been shown to generate more complex linguistic structures (Evans & Craig, Citation1992). Indeed, answering questions posed by adults may have facilitated children using more linking words like conjunctions and prepositions, whereas pure peer talk may have enabled more use of negation and interjections.

Lastly, as expected, the most frequently used lexemes in Hebrew were function words. For example, “this”, “I”, “no”, “the”, “to me”, and “and” were among the top six most frequently used words in the composite list. Nouns did not appear in the top 20 words. These six words may be considered core words for vocabulary selection and be used for a variety of pragmatic functions, including requesting, affirming, and negating, as well as generating grammatically correct structures that thereby support language growth (van Tatenhove, Citation2009; Witkowski & Baker, Citation2012).

Overlapping words

A comparison across the two conditions, peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk, shows that despite the different elicitation methods for the language samples, 90% (n = 18) of the top 20 most frequently used lexemes in each condition overlapped and accounted for 43.5% of the tokens in the composite list. Moreover, a comparison of the two conditions yielded a list of 337 overlapping lexemes across the samples, accounting for 87.3% of the tokens in the composite list. These findings are in line with the current literature in which core vocabulary words were found to be consistent across activities and topics (Banajee et. al, 2003; van Tilborg & Deckers, Citation2016). For example, Banajee et al. found that that all 50 children used the same most frequently used nine words (e.g., “I”, “no”, “yes/yeah”, “want”, “it”, “that”, “my”, “you”, and “more”) as well as the words “go”, “who”, “some”, “help”, “mine”, “the”, “is”, “on”, “in”, “here”, “out”, “off”, and “all done/finished”. A comparison of this study’s top 20 most frequently used Hebrew lexemes to previous studies of English indicates they also appear in the top 50 English words, except the accusative marker “et” (את) which is unique to Hebrew.

Specific language characteristics

Beyond the cross-linguistic similarity in the Hebrew and English core vocabulary items, it is also important to look at specific language characteristics (lexicon, grammatical categories), For example, the Hebrew accusative marker et is one of the most frequently used words in the language. Indeed, it ranked in the top 20 lexemes used by the Hebrew-speaking children in this study, but since it has no English equivalent, it does not appear in the English core words lists at all. A limited comparison to one of the English core word lists reveals that of the top 20 most frequently used words in the Hebrew sample, only seven words (35%) are also ranked in the top 20 most frequently used words in English (“I”, “that”, “what”, “the”, “this”, “no”, and “and”; Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015). Given the reliance on English language core vocabulary lists that is currently common in selecting vocabulary to include in AAC systems for children who speak Hebrew, it is important to consider the vocabulary lists identified in this study: the top 200 words in the composite list and the 337 overlapping lexemes list, when selecting core vocabulary for Hebrew-speaking children who use AAC.

Clinical Implications

The similarities in vocabulary size and content/function word distribution between lists of most frequently used words in Hebrew and English may be evidence of a generalized pattern for a core vocabulary and appear to support the inclusion of a small set of frequently occurring (200–400) words in AAC systems. The results of the present study also suggest the potential utility of the word list as a reference for core vocabulary selection for Hebrew-speaking preschool children who require AAC. The Hebrew word list includes function and content lexemes from different grammatical categories, including a specific grammatical category unique to the Hebrew language, namely, the accusative marker “et” (את). The unique characteristics of Hebrew as a Semitic language with rich morphology should be taken into consideration in selection of core words in the communication systems.

To reduce the load of navigation and to facilitate motor planning of the target words, we propose to consider the selection of words for beginning communicators as follows: To include the most frequently used words (inflected forms) on the home page by lexical categories; and less frequently used words could be represented as lexemes (i.e., in their default or uninflected form). For example, for a boy who use AAC, the verb “want” will appear in its masculine singular form “roce” want.M.SG.PRES [“wants”] on a home page. Other, less frequent forms of the verb (e.g., rocim want.M.PL.PRES [“we want”], “raciti” want.1PL.PST [“wanted”]) would appear under the lexeme “lircot” want.INF [“to want”] and would require the user to navigate through the inflectional paradigm of the verb to select the desired form using their meta-linguistic knowledge.

The results of this study also support including function words in communication aids (Boenisch & Soto, Citation2015). As stated before, it may be recommended to target the most frequently used word form for each lexeme under the function words. For example, one of the most frequently used function words in the Hebrew sample is the possessive lexeme “shel” (of) but its most frequent word form on the list was “sheli” [“of + me = mine”]; therefore, a recommended practice might be the appearance of the word form “sheli” [“of + me”] on the homepage of the communication device, while other forms of “shel” [“of“], such as “shelxa” [“of + you = yours”], “shelanu” [“of + us = ours”], would appear under the lexeme “shel”, necessitating the user to navigate through the inflectional paradigm of the preposition “shel” in order to select the target form.

For language growth, it is important to use a systematic language intervention that targets the most frequently occurring function and content words in Hebrew, as function words need to be learned in the context of a sentence.

Limitations and future directions

In the present study a preliminary word list served as a reference for core vocabulary selection for preschool-aged Hebrew-speaking children who use aided communication. Nonetheless, the current research has some limitations that need to be considered. Although participants were around the same age and their communication behavior was sampled from two different conditions, there were only 12 participants; however, there are precedents of other studies with less participants that established word lists that were regarded as core vocabulary.

Second, the assignment of most words into lexical categories was based on Hebrew grammar books, dictionaries, and the Hebrew Language Academy website resource, rather than on natural context. Given that Hebrew’s present participles can function as nouns, verbs, or adjectives without an overt change of form, a context-based analysis could have proven useful for part-of-speech disambiguation. On the other hand, given that the same word form can function as several parts of speech simultaneously, it should not make a difference for users of AAC, who can use the same form in different communicative contexts. Third, commonality scores (i.e., the number of participants using a specific word) were not considered in the identification of the core vocabulary.

Furthermore, additional research is needed to identify core vocabulary produced by different populations, including children with intellectual disabilities and autism spectrum disorder. It is also necessary to test how the identified vocabulary list of the current study could serve as a vocabulary reference for children who require AAC at different stages of AAC intervention and learning practice. Lastly, future research should address the issue of the AAC system layout given the differences between Hebrew and English and the challenges of applying what is known about layout organization in English to Hebrew.

Conclusion

This study adds to the growing body of cross-linguistic research conducted to assist professionals in selecting a core vocabulary for AAC systems. It is innovative in proposing and implementing a systematic methodology used in the AAC field for determining a word list to serve as a reference for core vocabulary selection for Hebrew-speaking children who use AAC. No pronounced differences were found in core vocabulary size or distribution of content and function words among the top 100 and 200 most frequently used words of the Hebrew-speaking children, between the two different conditions (peer talk and adult-mediated peer talk) or in comparable studies in English. This suggests the possibility of an underlying consistency in words included in the core vocabulary used by children across settings and languages.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Bat-Hen Simhi, Or Ohana, Adi Hadad, Tal Flour, Ortal Vered, Shefi Shukrun, Matan Shemi, and Jonathan Feldman for their assistance throughout the study in data collection, transcription, and coding. Special thanks to Prof. Sharon Armon-Lotem for her valuable feedback on issues relating to linguistic disambiguation and to Dr. Chen Gafni for his consultation on language sampling analysis. The authors thank the editors and anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on various versions of this paper. Lastly, the authors thank all the children and their parents for participating in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The following abbreviations are used in this paper: Person = 1, 2, 3. SG = singular; PL = plural; F = feminine; M = masculine; DU = dual; DIM = diminutive; PRES = present tense; PAST = past tense; FUT = future tense; IMP = imperative. INF = infinitive; P1 = CaCaC; P2 = niCCaC; P3 = CiC(C)eC; P4 = hitCaC(C)eC; P5= -hiCCiC.

2 Bob the Builder is a British animated children’s series created by Keith Chapman

3 Playmobil® is a brand of the Horst Brandstätter Group, headquartered in Germany. https://www.playmobil.cn/en/about/

4 Philips DVT1150® is a product of Philips Speech Processing Solutions www.dictation.philips.com/products/audio-video-recorders/voicetracer-audio-recorder-dvt1150

References

- Adamson, G. W., & Boreham, J. (1974). The use of an association measure based on character structure to identify semantically related pairs of words and document titles. Information Storage and Retrieval, 10(7-8), 253–260. doi:10.1016/0020-0271(74)90020-5

- Ashkenazi, O., Ravid, D., & Gillis, S. (2016). Breaking into the Hebrew verb system: A learning problem. First Language, 36(5), 505–524. doi:10.1177/0142723716648865

- Balandin, S., & Iacono, T. (1999). Crews, wusses and whoppas: Core and fringe vocabularies of Australian meal-break conversation in the workplace. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 15(2), 95–109. doi:10.1080/07434619912331278605

- Banajee, M., Dicarlo, C., & Stricklin, B. S. (2003). Core vocabulary determination for toddlers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 19(2), 67–73. doi:10.1080/0743461031000112034

- Berman, R. A. (1985). The acquisition of Hebrew. In D. I. Slobin (Ed.), The crosslinguistic study of language acquisition: Vol. 1. The data; Vol. 2. Theoretical issues (pp. 255–371). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Berman, R. A. (1993). Marking of verb transitivity by Hebrew-speaking children. Journal of Child Language, 20(3), 641–669. doi:10.1017/s0305000900008527

- Beukelman, D., Jones, R., & Rowan, M. (1989). Frequency of word usage by nondisabled peers in integrated preschool classrooms. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 5(4), 243–248. doi:10.1080/07434618912331275296

- Beukelman, D. R., & Light, J. C. (2020). Vocabulary selection and message management. In D. R. & J. C. Light (Eds.), Augmentative & alternative communication: supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (5th ed., pp. 159–180). Brookes Publishing.

- Blum-Kulka, S., & Dvir-Gvirsman, S. (2010). Peer interaction and learning. In P. P. B. McGaw (Ed.), International encyclopedia of education. (3rd ed., pp. 444–449). Elsevier.

- Boenisch, J., & Soto, G. (2015). The oral core vocabulary of typically developing English-speaking school-aged children: Implications for AAC practice. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(1), 77–84. doi:10.3109/07434618.2014.1001521

- Clark, E. V. (1993). The lexicon in acquisition. Cambridge University Press.

- Coffin, E. A., & Bolozky, S. (2005). A reference grammar of Modern Hebrew. Cambridge University Press.

- Cucchiarini, C. (1996). Assessing transcription agreement: Methodological aspects. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 10(2), 131–155. doi:10.3109/02699209608985167

- Dromi, E. (1987). Early lexical development. Cambridge University Press.

- Evans, J. L., & Craig, H. K. (1992). Language sample collection and analysis: Interview compared to Peer Talk assessment contexts. Journal of Speech and Hearing Research, 35(2), 343–353. doi:10.1044/jshr.3502.343

- Erickson, K. A., Geist, L., Hatch, P., & Quick, N. (2021). The challenge of symbolic communication for school-aged students with the most significant cognitive disabilities. In B. Ogletree (Ed.), Augmentative and alternative communication: challenges and solutions (pp. 253–282). Plural Publishing.

- Fenson, L. (2007). MacArthur-Bates communicative development inventories. Paul H. Brookes Publishing Company.

- Ford, J. H., Gaskill, M. J., & Lemp, J. (2008). What? you want me to do a language sample? Perspectives on Swallowing and Swallowing Disorders, 9(4), 135–139. doi:10.1044/sbi9.4.135

- Gendler-Shalev, H., & Dromi, E. (2022). The Hebrew Web Communicative Development Inventory (MB-CDI): Lexical development growth curves. Journal of Child Language, 49(3), 486–502. doi:10.1017/S0305000921000179

- Glinert, L. (2017). Modern Hebrew: An essential grammar. Routledge.

- Hattingh, D., & Tönsing, K. M. (2020). The core vocabulary of South African Afrikaans-speaking grade R learners without disabilities. The South African Journal of Communication Disorders = Die Suid-Afrikaanse Tydskrif Vir Kommunikasieafwykings, 67(1), e1–e8. doi:10.4102/sajcd.v67i1.701

- Hill, K., Kovacs, T., & Shin, S. (2014). Reliability of brain-computer interface language sample transcription procedures. Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development, 51(4), 579–590. doi:10.1682/JRRD.2013.05.0102

- Lahey, M., & Bloom, L. (1977). Planning a first lexicon: Which words to teach first. The Journal of Speech and Hearing Disorders, 42(3), 340–350. doi:10.1044/jshd.4203.340

- Laubscher, E., & Light, J. (2020). Core vocabulary lists for young children and considerations for early language development: A narrative review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 36(1), 43–53. doi:10.1080/07434618.2020.1737964

- Levie, R., Ashkenazi, O., Eitan Stanzas, S., Zwilling, R. C., Raz, E., Hershkovitz, L., & Ravid, D. (2020). The route to the derivational verb family in Hebrew: A psycholinguistic study of acquisition and development. Morphology, 30(1), 1–60. doi:10.1007/s11525-020-09348-4

- Loncke, F. (2020). Augmentative and alternative communication: Models and applications. Plural Publishing.

- Liu, C., & Sloane, Z. (2006). Developing a core vocabulary for a Mandarin Chinese AAC system using word frequency data. International Journal of Computer Processing of Languages, 19(04), 285–300. doi:10.1142/S0219427906001530

- MacWhinney, B. (2000). The CHILDES project: Tools for analyzing talk (3rd. ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Maital, S. L., Dromi, E., Sagi, A., & Bornstein, M. H. (2000). The Hebrew communicative development inventory: Language specific properties and cross-linguistic generalizations. Journal of Child Language, 27(1), 43–67. doi:10.1017/s0305000999004006

- Mngomezulu, J., Tönsing, K. M., Dada, S., & Bokaba, N. B. (2019). Determining a Zulu core vocabulary for children who use augmentative and alternative communication. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(4), 274–284. doi:10.1080/07434618.2019.1692902

- Marvin, C., Beukelman, D., & Bilyeu, D. (1994). Vocabulary-use patterns in preschool children: Effects of context and time sampling. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10(4), 224–236. doi:10.1080/07434619412331276930

- Mothapo, N. R., Tönsing, K. M., & Morwane, R. E. (2021). Determining the core vocabulary used by Sepedi-speaking children during regular preschool activities. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 23(3), 295–304. doi:10.1080/17549507.2020.1821774

- Morrow, D. R., Mirenda, P., Beukelman, D. R., & Yorkston, K. M. (1993). Vocabulary selection for augmentative communication systems: a comparison of three techniques. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 2(2), 19–30. doi:10.1044/1058-0360.0202.19

- Ravid, D. (2006). Semantic development in textual contexts during the school years: Noun Scale analyses. Journal of Child Language, 33(4), 791–821. doi:10.1017/S0305000906007586

- Ravid, D., Bar-On, A., Levie, R., & Douani, O. (2016). Hebrew adjective lexicons in developmental perspective: Subjective register and morphology. The Mental Lexicon, 11(3), 401–428. doi:10.1075/ml.11.3.04rav

- Robillard, M., Mayer-Crittenden, C., Minor-Corriveau, M., & Bélanger, R. (2014). Monolingual and bilingual children with and without primary language impairment: Core vocabulary comparison. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 30(3), 267–278. doi:10.3109/07434618.2014.921240

- Salmon, E. (2020). Lexical and grammatical aspects of the acquisition of prepositions in Hebrew: A sample study in the childhood years (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Tel Aviv University.

- Sanders, E. J., & Blakeley, A. (2021). Vocabulary in dialogic reading: Implications for AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 37(4), 217–228. doi:10.1080/07434618.2021.2016961

- Savaldi-Harussi, G., Lustigman, L., & Soto, G. (2019). The emergence of clause construction in children who use speech generating devices. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 35(2), 109–119. doi:10.1080/07434618.2019.1584642

- Savaldi-Harussi, G. & Fostick, L. (2021). Comparison of Preschooler Verbal and Graphic Symbol Production Across Different Syntactic Structures. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 702652. Comparison of Preschooler Verbal and Graphic Symbol Production Across Different Syntactic Structures. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 702652.

- Shacham, S. (2015). Efshar Lomar” Generic communication boards based on core words. Israel Augmentative and Alternative Communication Annual Journal, 31, 52–60.

- Shin, S., & Hill, K. (2016). Korean word frequency and commonality study for augmentative and alternative communication. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 51(4), 415–429. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12218

- Smith, M. M. (2015). Language development of individuals who require aided communication: Reflections on state of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md. : 1985), 31(3), 215–233. doi:10.3109/07434618.2015.1062553

- Soto, G., & Cooper, B. (2021). An early Spanish vocabulary for children who require AAC: Developmental and linguistic considerations. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 37(1), 64–74. doi:10.1080/07434618.2021.1881822

- Stuart, S., Beukelman, D., & King, J. (1997). Vocabulary use during extended conversations by two cohorts of older adults. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 13(1), 40–47. doi:10.1080/07434619712331277828

- Trembath, D., Balandin, S., & Togher, L. (2007). Vocabulary selection for Australian children who use augmentative and alternative communication. Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 32(4), 291–301. doi:10.1080/13668250701689298

- Uziel-Karl, S., & Berman, R. (2000). Where’s ellipsis? Whether and why there are missing arguments in Hebrew child language? Linguistics, 38(3), 457–482.

- Uziel-Karl, S. (2001). A multidimensional perspective on the acquisition of verb argument structure (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Tel-Aviv University. doi:10.1515/ling.38.3.457

- van Tatenhove, G. (2009). Building language competence with students using AAC devices: Six challenges. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 18(2), 38–47. doi:10.1044/aac18.2.38

- van Tilborg, A., & Deckers, S. R. (2016). Vocabulary selection in AAC: Application of core vocabulary in atypical populations. Perspectives of the ASHA Special Interest Groups, 1(12), 125–138. doi:10.1044/persp1.SIG12.125

- Witkowski, D., & Baker, B. (2012). Addressing the content vocabulary with core: Theory and practice for nonliterate or emerging literate students. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 21(3), 74–81. doi:10.1044/aac21.3.74