Abstract

Parental interventions can help parents use strategies to support their child’s language and communication development. The ComAlong courses are parental interventions that focus on responsive communication, enhanced milieu teaching, and augmentative and alternative communication. This interview study aimed to investigate the course leaders’ perceptions of the three ComAlong courses, ComAlong Habilitation, ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder, and ComAlong Toddler, and to evaluate their experiences of the implementation of the courses. Qualitative content analysis was used to analyze the interview data. Thereafter, three categories resulted from the findings: Impact on the Family, A Great Course Concept, and Accessibility of the Courses. The results indicate that participants perceived that the courses had positive effects on both parents and themself. Furthermore, it was described that parents gained knowledge about communication and strategies in how to develop their child’s communication; however, the courses were not accessible to all parents. The collaboration between the parents and course leaders improved, and course leaders viewed the courses as an important part of their work. The following factors had an impact on the implementation: several course leaders in the same workplace, support from colleagues and management, and recruitment of parents to the courses.

Communication is a process created and moderated in interaction with others (Bruner, Citation1983; Fogel, Citation1993). Language and communication are essential for a child’s general development and well-being. A child’s communication difficulties do not just lead to limited ability in communication. On the contrary, there is also a risk of limitations in reading, counting, concentrating, and forming relationships (McCormack et al., Citation2009). Communication and joint attention between the child and the communication partner are essential and facilitated by the ability to make eye contact, shift attention between an object and a person, and follow the eye gaze of the communication partner (Beuker et al., Citation2013; Kasari et al., Citation2006; Tomasello & Farrar, Citation1986). According to previous studies, parental interventions can help parents use strategies that support their children in language and communication development (Fey et al., Citation2006; Kaiser & Roberts, Citation2013; Roberts et al., Citation2019). One example of such interventions is the ComAlong courses, which are parental interventions aiming to give parents of children with communication difficulties knowledge and tools on how to help their children develop communication and language (Fäldt et al., Citation2020; Ferm et al., Citation2011.). The focus of the intervention is responsive communication (Brown & Woods, Citation2015; Roberts & Kaiser, Citation2011), enhanced milieu teaching (Fey et al., Citation2006; Mahoney et al., Citation2006), and augmentative and alternative communication to support communication (AAC) (Branson & Demchak, Citation2009; Light et al., Citation2019; Millar et al., Citation2006). AAC includes gestures, objects, manual signs, graphic signs, pictures, apps and speech-generating devices. The intervention consists of lectures, home assignments, discussions, modeling through video recordings, and mutual analysis of video recordings of the parents’ and child’s interaction in the home environment (Fäldt et al., Citation2020; Ferm et al., Citation2011). AAC is a vital part of ComAlong. It comprises AAC-related theory, tools and different methods, such as speech-generating devices, communication boards, photos and manual signs

ComAlong comprises several courses with somewhat different target groups. ComAlong Habilitation, including seven group sessions, targets parents whose children receive support from habilitation services for their intellectual disability, autism spectrum disorder, or motor impairment (AKKtiv, Citationn.d.; Ferm et al., Citation2011; Jonsson et al., Citation2011; Rensfeldt Flink et al., Citation2022). ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder, including six group sessions, is directed to parents with children with a developmental language disorder who receive support from a speech-language-pathology (SLP) clinic. ComAlong Toddler, which is aimed at parents of children early in the identification and diagnostic process, approximately one to three years of age, can be given in both habilitation services and the SLP clinic. ComAlong Toddler comprises two home visits and five course sessions. The home visits aim to identify the children in need of the course and individualize the intervention in the home setting. The initial home visit occurs before the course sessions, and the SLP assesses the child. The second home visit is a follow-up of the implementation of AAC, responsive communication and enhanced milieu teaching at home and supports the parents using the strategies learned during the course (Fäldt et al., Citation2020). A further difference between the three interventions, based on the target group, is how and what type of AAC is being introduced. In ComAlong Habilitation, more comprehensive AAC methods (e.g., speech generating devices) are often presented, while whereas (ComAlong Toddler, instead focuses on photos, objects, and manual signs.

Two course leaders, one of whom must be a speech-language pathologist, conduct the ComAlong courses. Course leaders attend an accredited 3-day training course (Jonsson et al., Citation2011). The prospective course leaders receive a booklet or a binder with detailed information and access to a website containing all the course material, including PowerPoint presentations and examples of AAC, to hand out during the course sessions. For ComAlong Habilitation and ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder, the prospective course leaders receive video examples during training to use in the course sessions, showing the strategies presented. In ComAlong Toddler, public video examples from Region Uppsala are used (https://regionuppsala.se/tidigintervention; Region Uppsala I. o. f., Citationn.d.).

In the course leader education for ComAlong Toddler, the prospective course leaders conduct a home assignment between the second and third day of training. They reflect on the implementation of ComAlong Toddler in their workplace and video record themselves when coaching the strategies introduced in ComAlong. The video-recorded coaching is shown at the following training course session to allow for self-reflection, individual feedback, and peer learning between the prospective course leaders. Together, this gives the prospective course leaders an experience of the feelings that can arise when video recording oneself. Every second year, there is a course-leader meeting to discuss the latest developments regarding ComAlong and relevant research.

The ComAlong interventions have been implemented in different parts of Sweden and the Nordic countries (AKKtiv, Citationn.d.). An implementation process can be described as an attempt to introduce something new in an organization (Greenhalgh et al., Citation2004). Implementing a method or intervention is not a linear process, and there is a need for different strategies to identify challenges on various levels (Grol & Grimshaw, Citation2003). There are other models, theories, and frameworks for analyzing, planning, and evaluating an implementation process. One framework for evaluation is Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) (Glasgow et al., Citation1999). There is a need for qualitative studies using RE-AIM, as the qualitative approach can enrich the understanding of the implementation and give an insight into why specific results occurred (Holtrop et al., Citation2018).

Even though the ComAlong interventions have been delivered in several Nordic countries since 2005, evaluation of course leaders’ experiences is sparse. In a previous study, four course leaders and four parents were interviewed regarding ComAlong Habilitation (Ferm et al., Citation2011). However, course leaders’ experiences of ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder or ComAlong Toddler have not yet been studied thoroughly; nor has there been any studies evaluating the barriers and facilitating factors for implementing these interventions. Even though the three courses are delivered in three different settings and, to some degree, other target groups, the content and structure of the courses are similar. The barriers and facilitators may differ between the settings, and the analysis has considered the specific course given by the participant. Studying course leaders’ experiences in-depth further evaluates the courses and provides valuable information for future development and implementation of such interventions. The aim of this study was to investigate the course leaders’ subjective perceptions of the ComAlong courses and to evaluate their experiences of implementing the courses in relation to Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, and Maintenance.

Method

Research design

This qualitative study used semi-structured individual interviews via a videoconferencing platform. The interviews were performed and transcribed by the first author. Qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach was chosen to obtain a deep understanding of the course leader’s experiences (Lindgren et al., Citation2020). Findings are reported using Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ) guidelines (Tong et al., Citation2007). This study was conducted according to the ethical guidelines described in the Helsinki Declaration. According to Swedish legislation, no ethical approval was necessary as no sensitive personal data was collected.

Researchers

The first and second authors were both SLPs. The first author had a superficial knowledge of ComAlong. The second author developed ComAlong Toddler and had been conducting ComAlong Habilitation, ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder, and ComAlong Toddler courses since 2011.

Participants

In order to be included in the study participants had to be trained in one of the three ComAlong courses: ComAlong Habilitation, ComAlong Developmental Language Disorder, or ComAlong Toddler; and be working in Swedish habilitation services or a speech-language-pathology clinic (SLP Clinic) in Sweden. Recruitment was performed through e-mail and posts on social media. Some of the participants were recruited through snowball sampling. When course leaders showed an interest in participating in the study, an information letter was sent by e-mail to the respondent. Prior to the interviews, the participants were informed about the study, that participation was voluntary, and that they had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. Oral consent to participate was obtained before the interview started. A total of 18 course leaders (16 SLPs, one occupational therapist, and one special educator) participated in the study. The participants worked in 14 different cities, from the south to the north of Sweden. Some were newly trained course leaders and some had taught the course for several years (). The number of courses taught varied, from less than five to more than 10. Even though the aim was to obtain a geographical distribution of participants, four of the respondents worked in one of Sweden’s metropolitan areas and two in the same medium-sized city.

Table 1. Description of participants (N = 18) regarding version delivered, course time period, and number of courses taught.

Materials

Interview guide

An interview guide (Appendix), based on the implementation framework RE-AIM (Glasgow et al., Citation1999) was developed by the research group in collaboration with external researchers having extensive experiences in qualitative studies. The interviews started with questions about the participants’ backgrounds. Specifically, the questions focused on the facilitators and barriers for implementing the courses, the outcome and accessibility for parents, adaptions and use of the courses, and thoughts about maintaining the intervention at the unit. Probing questions were used to evolve participants’ answers, for example, when they gave a short or vague answer.

Video conferencing tools

Procedures

One pilot interview was performed with participant 1. This interview and was included in the Results because it did not lead to any changes in the interview guide. After one participant described ways of maintaining knowledge and developing their roles as course leaders, the question “How do you maintain your knowledge?” was added (Interview 9). The interviews were conducted in Swedish, using video conferencing tools, and lasted between 20 and 57 min.

The interviews were audio-recorded and then transcribed verbatim by the first author. Furthermore, the participants did not get the transcripts in return.

Data analysis

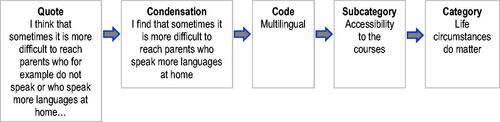

Qualitative content analysis with an inductive approach was used to analyze the data (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004) during a 5-week period. The analysis was performed using Microsoft Excel. The audio recordings and transcribed interviews were reviewed several times and there after separated into meaning units such that every unit had one single meaning by the first author. Thereafter, the meaning units were condensed and coded by the first author. The codes were categorized, inductively into subcategories and, thereafter, merged into categories. For every step in the analysis, a higher level of abstraction was sought (). The categorization process was repeated several times in cooperation between the first and second authors, who discussed the subcategories and categories until a consensus was reached, and the codes analyzed were divided into mutually exclusive subcategories and categories.

Results

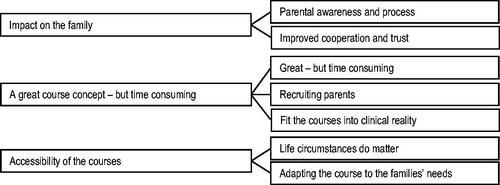

Categories (n = 3) and subcategories (n = 7) are illustrated in . The categories are presented with illustrative quotes from the interviews.

Impact on the family

This category comprised two subcategories: (a) Parental awareness and process, and (b) Improved cooperation and trust.

Parental awareness and process

Generally, the participants explained that they observed that the intervention improved parents’ awareness of communication and that communication includes more than just verbal language. Video-recorded home assignments viewed during the sessions were identified by the participants as partly contributing to the increased parental understanding. The participants also described that parents obtained tools to support their child’s communication and knowledge regarding AAC. However, participants noticed that some parents still did not understand that they played a role in developing their child’s communication. “I think that the parents become more aware of how they can promote their mutual communication in everyday life. That is probably the biggest difference and that they can see all the little things they can do”. (P8)

Furthermore, the participants reported on the development, both for children and parents, where the parents used AAC in communication with their child and seemed appreciative of AAC. For example, the participants noticed an increased use of communication boards in the children’s and parents’ home settings. They described the children as being more interested in communicating, increasing their use of AAC, and engaging in more eye contact.

The intervention was described as a process, where the parents gained insight as it enhanced their awareness of the child’s level of communication, abilities, difficulties, and general development. They stated that the process could be demanding and emotional.

Some parts of the course can evoke strong feelings among the parents such as sadness or frustration. It isn’t a negative impact of the course. They have those feelings anyway. It is rather a possibility for them to air those feelings; so, it’s something positive in the end. (P9)

According to the participants, the process was facilitated when the parents met other parents in similar life circumstances. The group dynamic was also considered to matter for the outcome. “Above all, we’ve experienced that a lot of parents find it valuable to meet other parents in the same situation, to take part of each other’s video recordings and tips and tricks”. (P11)

Improved cooperation and trust

Participants working in SLP clinics perceived that the course made parents more positive toward receiving further assessments of their child’s development. They also shared that there was a transition during the intervention, as the parents realized that they, in the course, did not need to advocate for their child’s right to be part of interventions.

During the first course session, some parents can be quite dominant, but then they relax and realize that “I don’t need to fight for my child’s health care here like I usually need to. I can just be a parent here and acknowledge that this is hard”. (P13)

The courses were described as creating a mutual language between the course leader and parents, which led to better collaboration in future interventions. The participants explained that the courses resulted in parents being more independent and thus taking a more active role in future interventions.

They have a lot of knowledge about communication and their own role as a parent. It is much easier to work after the course. Because they aren’t waiting for an SLP, they think, “what can I as a parent do now?” (P13)

As a result of the courses, the participants felt they had an enhanced understanding of the families’ life situations, resulting in a more sensitive approach to the parents’ needs. “I get more understanding of the overall situation, and then we can have better discussions that are more suited to them. We discuss together in a more equal way”. (P9)

The participants’ perceptions of what the parents wished for and the need for further interventions differed. Some participants working in the habilitation services voiced an increasing need for interventions. The need for support was less immediate after the intervention but increased with time. “But we see after the course that parents want more, rather than having had enough. They have become aware of what they need and want even more. You can’t give the course and then that’s it”. (P15) Participants working in the SLP clinics expressed that the courses resulted in less need for further SLP interventions.

Participants also mentioned that they had been told that the cooperation with parents in other settings had improved post intervention. “We have received positive feedback from different levels of care around the child. The special educators in the preschools can call to say that they have much better conversations with the parents after the course”. (P9)

A great course concept – but time consuming

This category comprised three subcategories: (a) Routines and delivery, (b) Parent recruitment, and (c) Clinical reality of the courses.

Routines and delivery

Participants appreciated the explicit instructions on how to deliver the intervention and the comprehensive course material. They further described the course sessions as a combination of theory and model learning, and some participants included role-play. “It says exactly what to do, so that’s what I’ve done. That’s kind of unusual for me, but it has worked out well. It’s covered pretty much everything”. (P1)

The preparations for the course sessions were considered time-consuming, particularly initially in the implementation process. Registrations and contact with parents before the sessions were viewed as being labor intensive. On the other hand, the participants stated that there was a greater number of children who received interventions through the courses compared to earlier, as the waiting lists for individual treatment were very long in the SPL clinics. They perceived the courses as a specific intervention for the youngest children in the SLP clinics. “It fits in really well as we can offer parents something when the children are too young for us to work with them directly”. (P10)

As part of ComAlong Toddler, home visits were perceived as an advantage. The home visits enabled the participants to engage with parents who typically did not attend visits at the clinic; moreover, it enabled observations of the child and the parent in the child’s home environment.

Recruiting parents

The procedures to invite the parents to the intervention differed between settings and participants. In the habilitation services, it was essential to prioritize ComAlong over other interventions to ensure that parents were not overwhelmed by too many interventions during the same period. In the habilitation services, colleagues often informed and invited parents to the courses. The participants explained that there were difficulties in motivating parents to attend the courses. In some cases, this challenge was deemed as affecting the implementation of the courses. Factors that facilitated the parental attendance in SLP clinics and habilitation services were having a prior relationship with them and instances where there was an invitation through a personal contact. “With a lot of parents, you need to make a personal contact, motivate why they should attend the course, rather than they themselves requesting the intervention or signing up by themselves”. (P5) Some participants explained that they only invited parents who could adopt the course content. This was foremost described by participants working in habilitation services. Other participants invited all parents.

Fit courses into clinical reality

The courses and giving parents knowledge about their child’s difficulties were described as unquestionable parts of the participants’ work assignment. “It fits well with the mindset of the habilitation services, how we talk about responsive communication, communication, and communication development. This is what we work with all day long but in other ways and individually”. (P8) Moreover, the participants described that the intervention changed their own way of working, which had a positive effect on other interventions, with improved abilities to coach the parents and a more systematic patient work. “Before, I didn’t really have the words for many of the things we talk about. Even though I talked about them in some way, it wasn’t so clear and conscious”. (P8)

Participants’ experiences of other parental courses facilitated the implementation of the ComAlong. Some of them thought that experiences of the patient group as well as that of working with AAC, and having competent group leaders were deemed necessary. “It goes without saying that they should have experience of coaching parents and working with children. To have a lot of real-life examples for credibility”. (P12) From the participants’ perspective, a facilitating factor for implementing the intervention was having several course leaders at the workplace, as the courses were time-consuming. Several participants mentioned the need to have more course leaders in the workplace and that only a few colleagues were allowed to attend the course leader training course. “The teaching of new course leaders has been a bit neglected”. (P16)

Even though the intervention was considered an essential part of their work, participants working in the habilitation services felt that their working conditions were negatively affected. They wished to have more support from their coworkers with the administration of the courses. “But on the other hand, you don’t really have the time. I needed to run in the corridors and knock stuff together and laminate the communication boards. You don’t have the time to prepare”. (P4)

Participants experienced varied support from managers and colleagues, and low support was identified as a barrier to implementing the courses. Some participants working in the SLP clinics with ComAlong DLD expressed there was a low interest from the colleagues initially in the implementation process, which hindered the implementation. With time, the colleagues reconsidered and wished for similar interventions for other patient groups. The importance of discussing the courses with colleagues was highlighted, especially if one was a newly trained course leader. One participant, working in habilitation services, stated that giving several ComAlong courses with an experienced course leader could decrease the need for attending the course leader training course. Participants offering ComAlong Toddler mentioned that the training course was comprehensive, and they felt comfortable giving the course with two inexperienced course leaders.

As a result of having the course often, participants kept their knowledge up to date. The knowledge became more and more automatized with time and experience. They further described a need for network meetings and educational days. “I see a need for course leader meetings. To update your own role as a course leader and meet up again. Be updated on the latest research and what is going on nationally. That would be really positive”. (P4)

Accessibility of the courses

The category comprised two subcategories: (a) Life circumstances do matter, and (b) Adapting the courses to the families’ needs.

Life circumstances do matter

The participants felt that the intervention was less accessible to families with multiple languages or those with culturally diverse perspectives on how children develop language and communication. They described this group of parents as having less of a result from the course. However, some participants working in the SLP clinics with ComAlong DLD concluded that the multilingual parents had the highest attendance and best outcome. There were geographical differences in the use of interpreters during the course sessions. In some areas, interpreters were never used or very seldom used, excluding parents who could not understand Swedish. Some participants described that it was challenging to use interpreters, and they experienced that the communication between the parents and the course leader deteriorated when an interpreter was used. Participants working in the SLP clinics with ComAlong Toddler mentioned that they gave parents an individual intervention when there were no vacant courses with an interpreter. Other participants working in the SLP clinics described the courses with the interpreter as a method to reach more parents. Participants also saw a need for comprehensive information regarding multilingualism in the course material.

The participants mentioned that the parents’ life circumstances affected the intervention outcome and the attendance. They explained that they sometimes wished that the courses had more of an effect on parents who could use the knowledge from the courses in communication with the child. Moreover, they described that the courses did not always fulfill the parents’ expectations. Parents with a high level of education were reported as having better outcomes, but others described that the courses could have a better result than expected.

But we also have parents with like, a really low level of education. Before the course, they can be like, “I dunno if I wanna do all that I’ll wait until he starts talking. He is with me here on the farm driving the snow scooter, it’s all right”, and after the course, they have really developed. (P13)

Parents’ motivation, own difficulties, and difficulties in participating in a group setting were also described as affecting the outcome for parents. Participants explained that many families had multiple contacts with health care and authorities, had many children, and had difficulties in getting a leave of absence from work. Factors identified by the participants that affected parents’ opportunities to attend the courses include families’ economic situations, long geographical distances.

It doesn’t always fit in with the juggle of everyday life for all the parents. It is eight sessions, and a lot of parents have to travel for an hour and a half to get here. It isn’t easy for everyone to fit it all in. (P6)

According to the participants, the outcome depended on the children’s language and communicative competence. Participants delivering ComAlong Toddler in the habilitation services and the SLP clinics had varying opinions regarding who was best suited for these courses. Participants working in the habilitation services thought that the courses were suitable for parents of children with developmental language disorders. In contrast, participants working in SLP clinics believed that the course was ideal for parents of children with autism spectrum disorder and intellectual disabilities. Other participants thought that an acceptance of the child’s disabilities impacted the course outcome and parental attendance. “For some, it might have been too early in the process; they don’t take the information on board”. (P5)

Participants expressed that the course had the best outcome if parents attended all the sessions and both parents attended, but all courses had dropouts. Reasons for dropping out could be a lack of time or that the courses were too long. There were fewer dropouts in the ComAlong Toddler courses than during the ComAlong Habilitation courses. They also mentioned long waiting times as a reason why parents did not attend the courses. According to participants working in the SLP clinics, implementation of the courses meant long waiting lists for the interventions, as the referrals had increased. “One difficulty can sometimes be that families have to wait for a long time to come to us. Then, some can feel that ComAlong is offered at too low a level”. (P9)

Adapting the courses to the families’ needs

Participants described that they had modified the courses to be able to reach a variety of parents. These modifications related to the number and length of sessions, resulting in shorter and longer sessions and courses. However, these changes did not increase the number of parents attending the courses. Participants described that they adapted the intervention to meet the parents’ needs, such as parents who had difficulties in attending group sessions due to their disabilities. “It has been a bit tricky for parents to attend all eight sessions. We tightened it to six sessions, and that felt more manageable”. (P15)

Several participants described that they introduced AAC at an earlier stage to enable parents to use AAC during the course. They also selected which AAC to focus on based on the children’s and families’ needs, often single pictures, manual signs or enhanced gestures.

One participant claimed that the need to adapt ComAlong Toddler was less than ComAlong Habilitation. In the habilitation services, the participants occasionally delivered courses targeting parents to children with a specific diagnosis or approximately equal communication abilities. The reason for this was to reduce the risk of parents with a child having a lower ability than the rest of the children feeling distressed. Even though the home visits in ComAlong Toddler were a benefit, some participants had to replace the home visits with clinic visits due to the cost and lack of resources. The participants suggested that home visits were an improvement for the ComAlong Habilitation course. They described the home visits as an opportunity for course leaders to support the parent and the child in their home environment and help them to be able to generalize the course content.

Participants mentioned that a digital or an interactive version on the web could reach more parents. In that case, the opinion was that the digital procedure had to be taught during the training course for course leaders. “Several have asked for a web version, an interactive short version on the web. For those parents who really want a lot but who only have time between eight and ten at night”. (P16)

Furthermore, participants discussed how parents in regions with long geographical distances or parents with financial problems could be reached. Suggestions included an outreach clinic and to offer home visits. Those participants working in the SLP clinics with ComAlong Toddler discussed the possibility of reaching parents by having courses in other cities in the county, while participants working in the habilitation services had already tried this without success. Other suggestions were that parents who previously attended the courses could act as informants to other parents. According to the participants working in the SLP clinics, several children of the parents that attended the course underwent developmental assessments during the course period. These participants described a need for collaboration with child health services and clinics performing developmental assessments to reach out to all parents and more groups of parents. It was also mentioned that offering the courses earlier in the health care process, such as Child health services, would be ideal. One participant also explained that after the implementation of ComAlong Toddler, the Child health services had started to invite children at risk to additional visits for developmental surveillance. “This is a team effort; if something needs developing in any way, it would be the cooperation with the child health care services. To find ways to hold it all together. So that you reach everyone”. (P1)

Discussion

This study explored the experiences of course leaders who provided a parental intervention that combined responsive communication, enhanced milieu teaching, and augmentative and alternative communication. The experiences differ between the settings and courses given, mainly regarding facilitators and barriers, but the main results are consistent.

The intervention was described as a process, where parents could gain a greater insight and enhanced knowledge of communication and use of communication enhancing tools, including AAC. The participants described various accessibility issues and outcomes of the intervention, depending on parental factors, such as educational level; practical, cultural, and language barriers; and the child’s level of communication. Through the intervention, there was improved cooperation with the families, using a mutual language; moreover, the participants were able to get a better insight into the parents’ life circumstances. The barriers to implementation included time-consuming administration, difficulties in recruiting families to the intervention, few course leaders in the workplace, and inadequate support from managers and colleagues. Facilitators for implementation were access to prepared material, explicit instructions on how to hold the course, the balance between theory and modeling during sessions, and the courses matching the common approach to communication in the workplace. The results are discussed based on the chosen framework for evaluation in this study, RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) and the qualitative approach to RE-AIM described in Holtrop et al. (Citation2018).

Reach

The participating course leaders reported several reasons for parents not attending the courses, including difficulties getting a leave of absence from work, economic situations, geographical distances, and having multiple health care contacts, all of which correspond to previously identified intervention barriers (Lingwood et al., Citation2020; Pennington & Thomson, Citation2007). The barrier due to multiple health care contacts was mainly mentioned by participants working in habilitation services, highlighting the specific demands in this setting with children having multiple needs. In both the present study and Pennington & Thomson (Citation2007), the descriptions regarding accessibility differs between the participants. Some assert that the intervention is not accessible to parents with disabilities, low levels of education, and language barriers, while others claim that the intervention was suited for all parents. ComAlong was described as adaptable to match parents’ needs. The varying levels of access to educated translators may explain some of the differences in accessibility. Some regions never offered courses with translators, which results in inequalities (Williams et al., Citation2018). In the SLP setting, one reason for parents not participating in the courses was the long wait times for interventions. This presents a risk, as parental engagement decreases every month they must wait, and the probability of nonattendance increases with longer waiting times (Curran et al., Citation2015). Even though the intervention was depicted as a means to shorten wait times, the participants described that recruitment, preparations, and administration were time-consuming. These administrative demands could be minimized by more administration support, which the participants requested. If an intervention is provided at the right time and with less wait time, attendance might increase (Curran et al., Citation2015), leading to higher effectiveness.

The participants stated that the course was a demanding process for the parents, who could feel sorrow and distress upon realizing their children’s difficulties, which can be obstacles to AAC interventions (Moorcroft et al, Citation2021). As previously noted, having interactions with other parents (Fäldt et al., Citation2020; O'Toole et al., Citation2021; Pennington & Thomson, Citation2007; Rensfeldt Flink et al., Citation2022); was described as a facilitating factor in addressing the sorrow and distress.

Effectiveness

Previous studies investigating the effectiveness or outcome of parent-directed interventions in SLP services have shown that parents have tools and strategies to help their children communicate as well as increased insight into their child’s communication abilities, which are vital aspects of responsive communication (Amsbary, Citation2019; Fäldt et al., Citation2020; Ferm et al., Citation2011). Pennington and Thomson (Citation2007) found that parents were more responsive to the child’s attempts to communicate, after the Hanen Program. In the present study, the participants described that they perceived that parents obtained tools to support their child’s communication development and knowledge regarding AAC. It was also mentioned that some parents did not realize that they had a role to play in their child’s communication development. The participants also reported on the child’s development, for example, an increased interest in communicating, increased use of AAC, and enhanced eye contact. This is similar to the results found by O'Toole et al. (Citation2021), who studied different parent-child interaction therapies and Fäldt et al. (Citation2020), who described improvements in pre-verbal social skills.

The participants described enhanced parental knowledge and that they developed in their work with a new vocabulary and deepened knowledge, which, in turn, had a positive effect on other interventions. This is also mentioned in a study by Ferm et al. (Citation2011), where course leaders for ComAlong Habilitation explained that they talked about communication more frequently since they started giving ComAlong.

The outcomes of the courses, as described by the participants, included developing a mutual language between the parents and the practitioners and increased collaboration with the families, which resulted in better outcomes in future interventions. Specifically, parents were more active in forthcoming interventions and had enhanced knowledge about communication development and stimulating their child’s language.

Following the courses, the parents’ needs were different, depending on the setting. Practitioners working in habilitation described parents having an increased need for interventions with time. Those working in SLP clinics found there was a decreased need following the course. Prior research has shown that a family-centered approach in an intervention leads to increased self-efficacy in parents (Dunst et al., Citation2007). A family-centered approach and collaborative practice are deemed to be essential when support is needed for a child’s language development (Klatte et al., Citation2020).

Adoption and implementation

Participants discussed how the risk of parental distress could be reduced by targeting parents whose children had approximately equal communication abilities. These findings, as well as the study of ComAlong targeting children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities (Rensfeldt Flink et al., Citation2022), support the development of more specific ComAlong interventions, at least in the habilitation services. The obstacle with different communication abilities in the same course is not mentioned by parents attending ComAlong Toddler (Fäldt et al., Citation2020). Implementation in the RE-AIM framework includes structure regarding adaptions of the intervention and can assist in the analysis of why and how the intervention was changed (Holtrop et al., Citation2018). One of the most common adaptions mentioned by participants working in habilitation services was to minimize the number of sessions in the course, suggesting that the seven sessions are too many, given the demands placed on families in their everyday lives. In contrast, participating parents in Ferm et al. (Citation2011) agree that eight sessions were appropriate (4.4 on a 5-point scale) even though several parents commented on the number of sessions. Participants giving the ComAlong Toddler course described that the home visits were amended due to time constraints, even though the participants highlighted the benefits of home visits. The home visits were also suggested as an improvement of ComAlong Habilitation as these enabled individualization and coaching in the home environment which are considered as vital (Woods et al., Citation2011). By the described modification to introduce AAC earlier and focusing on single images, manual signs or gestures, course leaders can reduce the challenge for parents to implement AAC as described by Moorcroft et al. (Citation2021).

One result of the courses was that the practitioners came to an enhanced understanding of the families’ life situations, which can be described as barriers and facilitators of the parental implementation of strategies (Klatte et al., Citation2020). This enhanced understanding can, in turn, lead to a more specific response to the family’s needs. If practitioners take the time to explore parents’ priorities, resources, capabilities, values, and beliefs, a shared understanding of expectations, roles, and responsibilities will be achieved, leading to a better outcome for children (Klatte et al., Citation2020). A collaboration like this will bridge barriers and motivate parents to actively participate in interventions (Klatte et al., Citation2020), which the participants described as being a result of the courses.

Maintenance

The participants commented that collaboration and support from colleagues and leaders in the workplace affected the implementation and maintenance of the courses. Opinions on how well the courses seem to be rooted in colleagues and managers differ. Some viewed the courses as a prominent part of their work, while others fought for more colleagues to be trained and wanted more support from colleagues and managers. ComAlong is foremost presented on the website AKKtiv.se, which lacks information directed to managers and decision-makers (AKKtiv, Citationn.d.). The paucity of information on the website as well as the participants’ descriptions suggest that a bottom-up approach has been used to implement ComAlong, which impacts the maintenance of the intervention. There are many benefits with bottom-up implementation, which is seen as more effective and sustainable than top-down driven change (Gifford et al., Citation2012; Sabatier, Citation1986; Thomann et al., Citation2018); however, there is also a great need to engage all stakeholders in the implementation of interventions. This can result in a sense of ownership among colleagues and leaders, leading to better support and adaption and long-term maintenance. The need for support from colleagues to motivate parents to engage in communication interventions has also been found by (Pennington & Thomson, Citation2007) who investigated therapists’ experiences of providing the Hanen Program, where motivation from the team was the most successful method to involve parents. Engaging all stakeholders also leads to equity and transparency (Harden et al., Citation2018). The participants felt that equity in ComAlong was lacking, as some practitioners select which parents to invite based on who they think may benefit from the intervention; however, others stated that the intervention had a better outcome than what they had expected beforehand.

Clinical implications

Based on the experiences of the participants, there are benefits of implementing parental courses such as ComAlong, which combine responsive communication, enhanced milieu teaching, and AAC for children, parents, and clinicians. The intervention develops children’s communication, parents’ knowledge and use of communication enhancing strategies, improves parent-clinician teamwork, and increases clinicians’ competence. There are, however, barriers to implementation and maintenance of the interventions, such as administrative burden, deficient support from managers, workload, waiting time for interventions, and difficulties in recruiting families to be part of the intervention. The reach of ComAlong could be increased by offering web courses, developing the use of translators, and having target specific groups in the interventions.

Limitations and future directions

The recruitment of participants aimed at heterogeneity in terms of number of ComAlong courses they delivered, number of years since attending the course-leader training, and geographical spread. Although the sample was fairly heterogeneous with regard to experiences of giving the courses, the courses attended, and specific setting delivering the intervention, transferability might be affected by the predominance of participants from two major cities. Moreover, the participants’ interest in ComAlong as the sampling procedure did not reach practitioners that had not succeeded in giving the ComAlong course. A majority of participants were SLPs. Only one occupational therapist and one special educator participated in the study. Half of the participants and only two of the professionals were asked the question regarding how the knowledge gained during the course leader training was kept alive, which may have impacted the result. Although data analysis was performed by the two authors and discussed thoroughly until a consensus was reached, there was no external assessor involved in the analysis process, which may have affected reliability. In the results, the participants reported an increased parental awareness of communication och that parents obtained tools to support their child’s communication; however, it is important to take into consideration that this is the participants’ subjective point of view and not a description from the parents. Parents were not interviewed in this study and no objective data were collected. In the results, there is evidence of low accessibility to the courses; thus, there is a need to further investigate from a parental perspective, which factors contribute to the low accessibility and how to overcome these barriers. Furthermore, there is a need to investigate if the intervention is applicable to parents who experience social adversity.

Conclusion

The findings in the study indicate that ComAlong Habilitation, Developmental Language Disorder, and Toddler are courses that give parents knowledge and insight into their child’s communication difficulties, communication in general, and strategies to support their child’s communication development; as well as knowledge about AAC they used to increase their use of AAC in communication with their child. It was evident, however, that the courses were not easily accessible to all parents, depending on the parents’ life circumstances and availability of an interpreter. The findings also indicate that the courses make the parents understand that they have an active role in developing their child’s communication; in addition, the mutual language between the course leader and the parent increased. The courses were viewed as an unquestionable part of some of the participants’ work assignment. The results show that facilitating factors for implementing the courses and maintenance of the courses include having support from the management and colleagues and having several course leaders at the unit. In contrast, lack of support and the difficulty in recruiting parents can be obstacles to implementing the interventions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AKKtiv (n.d) AKK tidig intervention https://www.akktiv.se/

- Amsbary, J. A. (2019). An exploration of parents’ perceptions participating in an intervention for their toddlers with autism spectrum disorder [Dissertation/Thesis]. ProQuest Dissertations Publishing (Publication Number Dissertation/Thesis)].

- Beuker, K. T., Rommelse, N. N. J., Donders, R., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2013). Development of early communication skills in the first two years of life. Infant Behavior & Development, 36(1), 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.infbeh.2012.11.001

- Branson, D., & Demchak, M. (2009). Dec). The use of augmentative and alternative communication methods with infants and toddlers with disabilities: A research review. Augmentative and Alternative Communication 25(4), 274–286. doi:10.3109/07434610903384529

- Brown, J. A., & Woods, J. J. (2015, March 1). Effects of a triadic parent-implemented home-based communication intervention for toddlers. Journal of Early Intervention, 37(1), 44–68. doi:10.1177/1053815115589350

- Bruner, J. S. (1983). Child’s talk: Learning to use language. New York: Oxford University.

- Curran, A., Flynn, C., Antonijevic-Elliott, S., & Lyons, R. (2015). Non-attendance and utilization of a speech and language therapy service: A retrospective pilot study of school-aged referrals. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 50(5), 665–675. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12165

- Dunst, C. J., Trivette, C. M., & Hamby, D. W. (2007). Meta-analysis of family-centered helpgiving practices research. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 13(4), 370–378. doi:10.1002/mrdd.20176

- Ferm, U., Andersson, M., Broberg, M., Liljegren, T., & Thunberg, G. (2011). Parents and course leaders’ experiences of the ComAlong augmentative and alternative communication early intervention course. Disability Studies Quarterly, 31(4). doi:10.18061/dsq.v31i4.1718

- Fey, M. E., Warren, S. F., Brady, N., Finestack, L. H., Bredin-Oja, S. L., Fairchild, M., Sokol, S., & Yoder, P. J. (2006). Early effects of responsivity education/prelinguistic milieu teaching for children with developmental delays and their parents. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(3), 526–547. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2006/039)

- Fogel, A. (1993). Two principles of communication: Co-regulation and framing. In J. Nadel & L. Camaioni (Eds.), New perspectives in early communication development (pp. 9–22). Routledge.

- Fäldt, A., Fabian, H., Thunberg, G., & Lucas, S. (2020). “All of a sudden we noticed a difference at home too”: Parents’ perception of a parent-focused early communication and AAC intervention for toddlers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 36(3), 143–154. doi:10.1080/07434618.2020.1811757

- Gifford J, Boury D, Finney L, Garrow V, Hatcher C, Meredith M, Rann R. (2012) What makes change successful in the NHS? A review of change programmes in NHS South of England. Available at https://www.roffeypark.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/NHS-South-of-England-What-makes-change-successful-report1.pdf (accessed 7 July 2023).

- Glasgow, R. E., Vogt, T. M., & Boles, S. M. (1999). Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: The RE-AIM framework. American Journal of Public Health, 89(9), 1322–1327. doi:10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). 2004/02/01/). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. doi:10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Greenhalgh, T., Robert, G., Macfarlane, F., Bate, P., & Kyriakidou, O. (2004). Diffusion of innovations in service organizations: Systematic review and recommendations. The Milbank Quarterly, 82(4), 581–629. doi:10.1111/j.0887-378X.2004.00325.x

- Grol, R., & Grimshaw, J. (2003). From best evidence to best practice: Effective implementation of change in patients’ care. Lancet, 362(9391), 1225–1230. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)14546-1

- Harden, S. M., Smith, M. L., Ory, M. G., Smith-Ray, R. L., Estabrooks, P. A., & Glasgow, R. E. (2018). RE-AIM in clinical, community, and corporate settings: Perspectives, strategies, and recommendations to enhance public health impact. Frontiers in Public Health, 6, 71–71. doi:10.3389/fpubh.2018.00071

- Holtrop, J. S., Rabin, B. A., & Glasgow, R. E. (2018). Qualitative approaches to use of the RE-AIM framework: Rationale and methods. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 177–177. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-2938-8

- Jonsson, A., Kristoffersson, L., Ferm, U., & Thunberg, G. (2011). The ComAlong Communication Boards: Parents’ use and experiences of aided language stimulation. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 27(2), 103–116. doi:10.3109/07434618.2011.580780

- Kaiser, A. P., & Roberts, M. Y. (2013). Feb). Parent-implemented enhanced milieu teaching with preschool children who have intellectual disabilities. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 56(1), 295–309. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2012/11-0231)

- Kasari, C., Freeman, S., & Paparella, T. (2006). Jun). Joint attention and symbolic play in young children with autism: A randomized controlled intervention study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 47(6), 611–620. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01567.x

- Klatte, I. S., Lyons, R., Davies, K., Harding, S., Marshall, J., McKean, C., & Roulstone, S. (2020). 2020/07/01). Collaboration between parents and SLTs produces optimal outcomes for children attending speech and language therapy: Gathering the evidence. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 55(4), 618–628. doi:10.1111/1460-6984.12538

- Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Caron, J. (2019). New and emerging AAC technology supports for children with complex communication needs and their communication partners: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(1), 26–41. doi:10.1080/07434618.2018.1557251

- Lindgren, B.-M., Lundman, B., & Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108, 103632. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103632

- Lingwood, J., Levy, R., Billington, J., & Rowland, C. (2020). Barriers and solutions to participation in family-based education interventions. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 23(2), 185–198. doi:10.1080/13645579.2019.1645377

- Mahoney, G., Perales, F., Wiggers, B., & Herman, B. (2006, August). Responsive teaching: Early intervention for children with Down syndrome and other disabilities. Down’s Syndrome, Research and Practice, 11(1), 18–28. doi:10.3104/perspectives.311

- McCormack, J., McLeod, S., McAllister, L., & Harrison, L. J. (2009). A systematic review of the association between childhood speech impairment and participation across the lifespan. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 11(2), 155–170. doi:10.1080/17549500802676859

- Millar, D. C., Light, J. C., & Schlosser, R. W. (2006). The impact of augmentative and alternative communication intervention on the speech production of individuals with developmental disabilities: A research review. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 49(2), 248–264. doi:10.1044/1092-4388(2006/021)

- Moorcroft, A., Scarinci, N., & Meyer, C. (2021). “I've had a love-hate, I mean mostly hate relationship with these PODD books”: Parent perceptions of how they and their child contributed to AAC rejection and abandonment. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology, 16(1), 72–82. doi:10.1080/17483107.2019.1632944

- O'Toole, C., Lyons, R., & Houghton, C. (2021). A qualitative evidence synthesis of parental experiences and perceptions of parent-child interaction therapy for preschool children with communication difficulties. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 64(8), 3159–3185. doi:10.1044/2021_JSLHR-20-00732

- Pennington, L., & Thomson, K. (2007). It takes two to talk The Hanen Program and families of children with motor disorders: A UK perspective. Child: Care, Health and Development, 33(6), 691–702. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2214.2007.00800.x

- Region Uppsala, I. o. f. (n.d). Tidig intervention – Kom igång med lek och kommunikation. Region Uppsala. Retrieved 30-12-2021 from https://regionuppsala.se/tidigintervention

- Rensfeldt Flink, A., Åsberg Johnels, J., Broberg, M., & Thunberg, G. (2022). Examining perceptions of a communication course for parents of children with profound intellectual and multiple disabilities. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities, 68(2), 156–167. doi:10.1080/20473869.2020.1721160

- Roberts, M. Y., Curtis, P. R., Sone, B. J., & Hampton, L. H. (2019). Association of parent training with child language development a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Pediatrics, 173(7), 671–680. doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.1197

- Roberts, M. Y., & Kaiser, A. P. (2011). The effectiveness of parent-implemented language interventions: A meta-analysis. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 20(3), 180–199. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2011/10-0055)

- Sabatier, P. A. (1986). Top-down and bottom-up approaches to implementation research: A critical analysis and suggested synthesis. Journal of Public Policy, 6(1), 21–48. doi:10.1017/S0143814X00003846

- Thomann, E., van Engen, N., & Tummers, L. (2018). The necessity of discretion: A behavioral evaluation of bottom-up implementation theory. Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory, 28(4), 583–601. doi:10.1093/jopart/muy024

- Tomasello, M., & Farrar, M. J. (1986). Joint attention and early language. Child Development, 57(6), 1454–1463. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.1986.tb00470.x

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Williams, A., Oulton, K., Sell, D., & Wray, J. (2018). Healthcare professional and interpreter perspectives on working with and caring for non-English speaking families in a tertiary paediatric healthcare setting. Ethnicity & Health, 23(7), 767–780. doi:10.1080/13557858.2017.1294662

- Woods, J. J., Wilcox, M. J., Friedman, M., & Murch, T. (2011, July). Collaborative consultation in natural environments: Strategies to enhance family-centered supports and services. Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 42(3), 379–392. doi:10.1044/0161-1461(2011/10-0016)

Appendix

Interview guide for ComAlong course leaders

Background questions

Have you been a course leader? How many times?

When did you attend the course-leader training?

How long have ComAlong courses been offered at your workplace?

Main and probing questions

Explain how you deliver ComAlong courses

Have you done any adjustments to ComAlong to be able to deliver the courses? What adjustments? Why?

Has the introduction of ComAlong courses worked in your workplace?

What have you done to be able to implement ComAlong courses?

How has this been difficult/easy?

How does ComAlong relate/differ to your way of working?

Have you received support from your manager and colleagues in delivering ComAlong courses?

What has that been like?

What does your manager do to enable you to provide ComAlong courses?

How have ComAlong courses changed your way of working?

What impact have ComAlong courses had on parents and children?

Can you give an example of how ComAlong had a positive/negative/unexpected impact?

Has ComAlong had the desired impact?

Are some parents impacted differently by the courses than others? In what way?

Which parents access and attend ComAlong courses?

Are there some parents who do not have access to the courses? Why?

Are there some parents in particular who you would like to attend the course?

How could more parents get access to ComAlong courses?

Have any parents dropped out during ComAlong courses? If so, why have they dropped out?

Which parents do you invite to ComAlong courses? How are they invited?

Do you continue to offer ComAlong courses? Why/Why not?

How do you keep the knowledge you gained from the course leader training alive?

Have you attended a course leader network meeting?

Do you regularly discuss ComAlong in your workplace?

What do you think about the future of ComAlong?

Will you continue to provide ComAlong courses?

What needs to be done in order for you to provide the courses?

What might future course leaders need to provide the courses?

How do you evaluate the ComAlong courses at your workplace?

Is there anything else you want to tell me?