Abstract

Key word signing (KWS) is an unaided form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) and is frequently used by children with cognitive impairments and their families. Successful implementation of KWS requires a family environment that provides aided language input by modeling the signs. However, families face challenges implementing the signs in their everyday lives. KWS requires effort and sustained parental commitment. Users may also struggle with finding good learning resources and stimulating and enjoyable shared contexts for communication. Signed videos of popular children’s books may help to implement KWS and create a signing environment which exposes children and their families to KWS in meaningful ways. The aim of this study was to create videos of this type and investigate whether and how they might serve as an attractive medium of support for families’ KWS experience. Three families tested the videos. A triangulated qualitative study incorporating interviews and participant observation explored the families’ experience of using these videos as a context for shared communication. The findings suggest that picture book videos supplemented by KWS may be appropriate resources for the use of KWS in everyday family life. They serve as a child-centered activity involving KWS exposure, in which children and their families can participate joyfully and naturally.

The term “augmentative and alternative communication” (AAC) refers to a range of strategies and tools that replace or support natural speech. AAC can involve aided and unaided methods. While aided methods require external devices or tools (such as communication books or tablets), unaided methods rely on the user`s body, and include facial expressions and body language (Beukelman & Mirenda, Citation2013). Key Word Signing (KWS) is a commonly used form of unaided communication for children and adults with cognitive impairments. KWS programs have emerged in various countries around the world (e.g., United Kingdom, Australia, Ireland; Glacken et al., Citation2019). Various programs have found use in Germany; they include MAKATON (see http://www.makaton-deutschland.de/), GUK (see https://www.ds-infocenter.de/), and KWS, which incorporates signs from German Sign Language, the language of Germany’s Deaf community. These systems differ in the representation and performance of signs, but are all based on the principle of supporting the main words in a spoken sentence visually by means of natural gestures and manual signs.

Several studies confirm that the use of signing to accompany and support spoken language can have positive effects on communication skills in individuals with cognitive challenges concomitant with conditions such as Down syndrome, early childhood autism, and intellectual impairment (Clibbens, Citation2001; Launonen, Citation2019; Tan et al., Citation2014; Wagner & Sarimski, Citation2012; Wright et al., Citation2013). KWS has been shown to support the acquisition of speech (Pattison & Robertson, Citation2016; Vandereet et al., Citation2011) and to enhance language comprehension (Loncke et al., Citation2006; Rudolph, Citation2018). Parents of children with complex communication needs report that the use of signs reduces communicative frustration on both sides of the interaction, improves their child’s behavior, and enables them to participate more actively in family life (Glacken et al., Citation2019).

The family of a child who uses AAC plays a central role in the successful implementation of AAC strategies (Goldbart & Marshall, Citation2004). Family members provide crucial aided language input by modeling speech and a corresponding form of AAC in a real-life context (Senner et al., Citation2019). Several studies have found aided language input and modeling interventions to support the implementation of AAC (Chazin et al., Citation2021; Kent-Walsh et al., Citation2015; O’Neill et al., Citation2018; Sennott et al., Citation2016).

Notwithstanding their recognition of the positive effect that KWS can have on children’s communication, families face a range of challenges in the process of learning to communicate using KWS (Glacken et al., Citation2019). Incorporating AAC into day-to-day family life is time-consuming and requires sustained parental commitment. Parents experience it as overwhelming at times (Glacken et al., Citation2019). Successful communication using KWS requires continuous awareness and cognitive effort for the production of the manual signs (Rombouts et al., Citation2017). Given this, positive effects may only become apparent in the long term. Before a child can begin to produce signs themselves, they need substantial augmented input with KWS. The amount of time that can elapse between the family beginning to practise signing and the child actively adopting it can leave many parents in doubt as to their progress (Glacken et al., Citation2019).

Learning to use KWS may entail hesitancy in engaging with this unfamiliar communication form. The acquisition of KWS differs from that of spoken language in that family members need to acquire in a conscious process, approaching it as essentially a kind of foreign language and laboriously learning unaccustomed physical forms of expression and linguistic rules (Braun, Citation2000). Some parents are uncomfortable with using AAC in public due to concerns around the lack of awareness of AAC in broader society or around potential negative responses from people they encounter (Singh et al., Citation2017).

Appropriate training and support services for facilitating the successful acquisition and use of KWS are often in short supply for children and their families (Frizelle & Lyons, Citation2022). In German-speaking countries in particular, appealing and motivating learning material is scarce. Sign dictionaries in the form of large books and ring binders may prove too cumbersome for everyday use. The potential for misinterpreting photographs and illustrations with arrows and markings may mean that a non-specialist translates the sign into movement in an inaccurate manner (Appelbaum, Citation2016). Some collections of signs are now available as audiovisual media in apps (e.g., Wörterfabrik für Unterstützte Kommunikation UG. (n.d.). EiS-App: Eure inklusive Sprachlern-App [EiS-App: Your inclusive language learning app]. Retrieved May 8, 2024, from https://www.eis-app.de; Verlag Karin Kestner GmbH. (n.d.). Der Kestner: Das Wörterbuch der Deutschen Gebärdensprache [The Kestner: Dictionary of German Sign Language]. Retrieved May 8, 2024, from https://web.kestner.de/apps/), enabling caregivers to look up how to perform a sign and facilitating their learning. However, children who require AAC need to experience the use of signs in appropriate everyday interactions (Light & McNaughton, Citation2015).

Looking at picture books together offers many opportunities for experiencing KWS in everyday interactions between children and their parents. If parents or carers embed KWS in their reading of books, children receive high-frequency exposure to signs, which encourages vocabulary development (Frizelle et al., Citation2023; Quinn et al., Citation2020). Children’s participation, attention, and capacity to learn increase when they and their caregivers use KWS during shared picture book reading (Frizelle et al., Citation2023). However, even here, KWS use can fail if the picture books do not include line drawings of manual signs or if parents misinterpret such illustrations. Parents could learn how to use KWS by attending courses that incorporate the guidance of a KWS expert. In the ideal case, however, the day-to-day use of KWS in families would not require caregivers to invest additional time and energy in the endeavor.

In this article, we consider two factors which may support families in learning KWS and putting it into practice. The first of these is bringing the whole family actively on board with KWS; the second is the adoption of an authentic approach to communication development via the provision of enjoyable and meaningful interactions for communication that incorporate the use of KWS. These factors are closely interrelated. The unique role of caregivers in a child’s experience of language means that AAC interventions aligned with the needs of the whole family promise robust results (Goldbart & Marshall, Citation2004; Mandak et al., Citation2017).

Research findings on AAC suggest benefits from incorporating AAC strategies into everyday life as authentic interactions that stimulate the functional and communicative use of AAC in interactive exchanges and that are tailored to the child's individual interests (Light & McNaughton, Citation2015; Mandak et al., Citation2017). This means embedding AAC into activities that are meaningful and motivating to the child. The child should be free to choose what they want to engage with, meaning that the caregiver’s role is to fully follow the child’s impulses and to support the child with natural language teaching techniques (such as embedding the child’s utterances in a wider context, corrective feedback, and unconscious correction; Kaiser & Wright, Citation2013). Alongside training for parents that helps them promote effective interactions, families need opportunities for shared interactions that can develop their skills in communicating with one another (Light et al., Citation2019).

The use of digital media may also support the implementation of KWS. Parents regard technology-based resources, such as apps and DVDs, that use KWS as helpful (Glacken et al., Citation2019). Some collections of signs are now available as audiovisual media in apps, enabling caregivers to quickly look up how to perform a sign and facilitating their learning. The versatility of digital media allows authors of learning resources and users to choose from a wide range of formats, such as audio, video, text, and/or images, making such media useful in the process of recognizing, understanding, and retaining content that is the subject of learning (Kerres, Citation2018; Zorn, Citation2014; Citation2018). The incorporation of digital media into educational processes can thus help make learning more engaging and accessible for children with and without a cognitive impairment (Bosse et al., Citation2019; Siebert et al., Citation2018). In particular, audiovisual videos may be helpful for the specific issues of children who use AAC and their families. Like KWS, they present auditory and visual information simultaneously. Alongside the ubiquity they have attained via the use of mobile devices in day-to-day family life, short films and videos hold a variety of affective and social associations for children and their families. The enjoyment families gain from watching videos can be an important facilitator of communication (Neuß, Citation2012). Various studies have confirmed the assumption that audiovisual media can support the development of a foreign language under certain conditions (Gola et al., Citation2012; Holler & Schmidt, Citation2010; Kirch, Citation2008; Kirch, Citation2008; Lemish & Rice, Citation1986; Linebarger & Walker, Citation2005). This positive effect may be associated with the immersive element of audiovisual media, which sensitizes children to the sound of the language and the real-world use of individual words, as well as creating learning situations that resemble those found in first language acquisition. Watching television is error-friendly because it does not involve conscious corrections or admonitions (Kirch, Citation2008). It is worth noting here that confirmation of the beneficial effects of audiovisual media is limited to specifically created educational broadcasts that adhere to appropriate design features such as embedding of content in scenarios relevant to viewers' lives, language appropriate for children, repetition, and encouragement to actively participate (through, for instance, the presenter directly addressing the audience; Anderson et al., Citation2000; Kirch, Citation2008; Linebarger & Walker, Citation2005; Wright et al., Citation2001). The study by Linebarger and Walker (Citation2005), which examined the relationship between exposure to television and language acquisition in infants and toddlers aged 6 to 30 months, reported positive outcomes for language acquisition where broadcasts are well-designed, incorporating, for example, a strong narrative and specific language-promoting strategies.

The indications from the existing literature prompt the assumption that audiovisual resources with a specific, needs-based design have a particular capacity to help children and their families meet the challenges they experience when communicating with KWS. The present study therefore follows up this lead by seeking to examine the potential of videos supplemented by KWS. We predicate this work on two key assumptions: First, videos can be an easy-to-use method of creating an environment in which children and their families are exposed to KWS and thus of supporting the use of signs in day-to-day family communication. Second, videos can be an appropriate method of establishing authentic, meaningful, and highly enjoyable shared communication activities including KWS for the whole family. These assumptions refer to theories on AAC modeling intervention approaches in naturalistic interactions; if someone is to learn to communicate using AAC methods, they should be immersed in environments that use AAC (Sennott et al., Citation2016).

Picture book videos are available that incorporate a translation into German Sign Language, but do not use spoken language; by contrast, KWS picture books with accompanying spoken language had yet to be produced. We therefore produced three picture book videos using KWS, in accordance with specific design principles as detailed in . AAC users - children and their families - subsequently watched the videos at home.

Table 1. Scientific findings on factors conducive to learning and the design decisions we derived from them

To evaluate the extent to which the videos met our assumptions, we needed to ascertain the views of children and their caregivers. We wished to identify whether children considered watching these videos with their families as an interesting and motivating activity which enabled them to engage in line with their abilities. In terms of the parents, we sought to establish whether they considered watching these videos to be an easy-to-use, meaningful, and enjoyable activity to share with their children that provided appropriate KWS input for both them and the children. We assumed that parents who took this view would be inclined to watch signed picture book videos regularly with their children, which could potentially increase their use of KWS as a method of communication. Everyday life with a disabled child is often full of time-consuming care and educational tasks over and above those required for a child without a disability; it is therefore important to avoid burdening parents with additional interventions that they might perceive as overwhelming and/or unpleasant. Unlike prior studies that have focused on training caregivers as instructors so they could carry out interventions with their children (one example is the study by Frizelle et al., Citation2023), this study proposed the use of signed picture book videos as an intervention that does not require prior training for the child’s caregivers. The central objective of this intervention is not the learning of a particularly large number of signs, but rather enabling families to experience a stimulating activity together and facilitating meaningful social interactions for families via rich and appropriate exposure to KWS. Even if a child does not sign actively, embedding KWS in audiovisual stories can support their comprehension of the stories’ content.

Our research questions were as follows:

First, how do children engage with videos showing picture books supplemented by KWS?

Second, how do parents experience watching signed picture book videos with their children as a shared context for communication?

Method

Research design

This study aimed to answer these questions using a qualitative exploratory design involving methodological triangulation for data collection, interpretation, and analysis. The choice of this design enabled us to closely study the experience of interaction in an everyday family activity. It provided an accurate, realistic, and expressive reflection of the realities of communication for children with cognitive difficulties. Further, it was suitable for meeting the challenges posed by the study’s topic, such as the limited verbal skills of the children and the lack of research into this matter to date. When working with people who have a cognitive impairment, it is particularly important to retain sufficient flexibility to adapt the research process to their needs; quantitative methods carry the risk of overly restrictive procedures. Another reason for employing methodological triangulation in the present study was to increase the validity and reliability of the individual cases studied; investigating a phenomenon using multiple methods on a small number of cases often produces more meaningful results than using one method on as many cases as possible (Flick, 2012).

We obtained the required ethical approval from the appropriate ethics bodies.

Participants

Three parent-child dyads participated in this study: Laura and her mother Carolin, Leo and his mother Susanna, and Ben and his mother Jennifer (all names are pseudonyms). They met the following criteria for inclusion in the study: (a) the children had moderate to severe cognitive impairments; (b) the children knew that they were able to communicate about things with someone else; (c) they had sufficient attention spans to engage for at least ten minutes; (d) the parents had positive attitudes toward the use of KWS; (e) the children were aged 3-5 years. To ensure that the children met criterion (b), we ascertained the developmental stage of their communication using the Communication Matrix (Rowland & Fried-Oken, Citation2010). We assigned the children to a level on the basis of their parent’s descriptions of their child’s communication skills. shows demographic information on the participating mothers and children.

Table 2. Participant demographics

Each of the participants provided informed consent.

Recruitment

Purposive sampling was used to identify suitable participants. We chose purposive sampling to focus in depth on small samples. Families were identified as suitable for the intervention after they had sought and received advice and information about methods of AAC at an advice and support center in Germany. In all cases, the center had recommended KWS, alongside other AAC methods, as suitable for the child. The first author of this paper, Meike Cruz Leon, worked at the center as an AAC consultant and was involved in advising these families. After having provided the advice, she contacted the families by telephone to explain the project and to ask them if they would like to participate in the study. We followed up by sending out information and asking for the participants’ informed consent.

Materials

We chose three children’s books that met three criteria: popularity with and familiarity to young audiences, occurrence of numerous repetitive sentence patterns and prompts, and vocabulary in keeping with children’s day-to-day lives. The books were written by Maar (Citation1998), Carle (Citation1987) and Rathmann (Citation2006).Footnote1

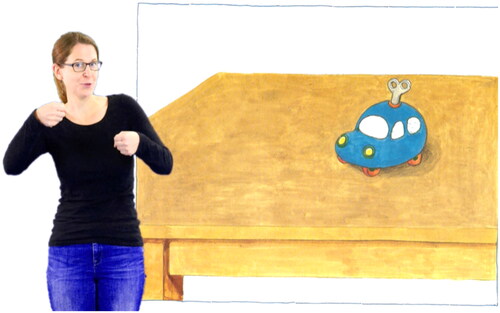

Creating the videos entailed filming the first author, Meike Cruz Leon, who is trained in KWS, reading the books aloud and performing KWS in real time (). We identified key words to sign using criteria as follows: Does the word contribute to the essential understanding of the sentence? Is the word part of the core vocabulary according to Sachse et al. (Citation2009) and can it be used in a variety of situations in everyday life? Is the word shown as an illustration on the relevant page of the book? This resulted in the inclusion of 35 signs in the video of Today is the Mouse's Birthday, 34 signs in Good Night, Gorilla, and 48 signs in The Very Hungry Caterpillar. The signs we used are based on German Sign Language; a professional sign language interpreter supported us with the translation process. At the end of the video, the presenter repeated the most important words from the story, their signs, and the corresponding graphic AAC symbolsFootnote2,Footnote3. Each video had a duration of 7-9 min.

Figure 1. Presenter reading the picture books aloud and performing key word signing Note. Illustration by Maar (Citation1998). Video by Meike Cruz Leon.

Procedures

Study setting

The study took place in the homes of the participating families. The families received five home visits for data collection.

Data collection

Data collection incorporated video recording of children`s behavior while watching the signed picture book videos and interviews with mothers about their experiences. On our first visit to their homes, the families received a tablet device containing the three picture book videos, which they were to keep and use for a period of around five weeks. Three further home visits at intervals of 1 to 2 weeks followed, at the convenience of the parents, during which we observed and video recorded the children during use of the videos.

For two of the children the videos were collected by the first author, Meike Cruz Leon. The other child did not engage when she was present; this child preferred to play and move about the room rather than sitting quietly in front of the video. The collection of video data therefore took place at a different time of day by a friend of the mother, with whom the child was familiar. The final body of material for analysis encompassed eight video recordings showing the participants interacting with the videos, three each of two of the children, and two of the other child.

We made a fifth home visit to interview mothers using the episodic interview technique as described by Flick (Citation2011), encouraging the participants to relate everyday situations involving the video resources on their own initiative while also asking specific questions (Flick, Citation2011).

Data analysis

Analysis of the video recordings aimed at evaluating the levels of enjoyment and engagement in the activity shown by the participating children, not at counting the number of signs they produced. As small children cannot communicate their engagement and enjoyment directly, we required a suitable method for observing and interpreting it. We sought to measure the children’s attention or involvement. One possibility could have been the use of the Pivotal Behavior Rating Scale (PVBRS; Mahoney, Citation1998), which serves to measure children’s “initiation and attention.” The videos run continuously without stopping; the fact that, under these conditions, an involved child watching the video would be unlikely to initiate any activities led us to refrain from measuring initiation. The PVBRS (Mahoney, Citation1998) component attention might have served as a suitable measure. We chose, however, to use measures of involvement from the Leuven Involvement Scale (Laevers et al., Citation2010) as the most suitable aids to our interpretation of children’s expressions of engagement. This scale evaluates the behaviors of small children while engaging in activities (MacRae & Jones, Citation2023). Basing it on Piagetian developmental psychology, Laevers draws on Csikszentmihalyi’s theory of flow to set out the connections between involvement, enjoyment, and engagement. Csikszentmihalyi (Citation1990) describes flow as a state of complete absorption in an activity where the individual doing the activity perceives it as an appropriate challenge. Involvement and, by extension, flow will not occur if an activity either exceeds or falls below children’s level of competence (MacRae & Jones, Citation2023). We found the Leuven Involvement Scale useful for the present research due to its alignment with the assumptions underlying theories of child communication development, such as a need for activities to be motivating and the imperative to avoid explicit teaching and its focus on how the child engages. Involvement, in this context, means interacting with one thing with perseverance, concentration, and evident internal engagement (Laevers et al., Citation2010). Involvement is not amenable to direct and objective quantification; this notwithstanding, Laevers et al. (Citation2010) suggest nine indicators of a child’s internal engagement, which we set out below. Prior to the analysis, we drew up criteria for the interpretation of a behavior or response during viewing of the picture book videos as corresponding to one of the nine indicators. We give these criteria in parentheses after each indicator.

Concentration (eyes focus on the video or on the parent; external stimuli do not distract the child)

Energy (reacts to the content of the video by pointing to the screen, gesturing, signing, and vocalizing; shows enthusiasm and dedication; sits still rather than showing restlessness)

Complexity and creativity (shows a new behavior; varies in reactions rather than repeating routine responses)

Facial expression and posture (shows an emotional response, such as smiling or laughing, watches the screen intently; sits upright while watching)

Persistence (sits throughout the videos rather than moving away)

Precision (repeats attempt to sign and make gestures; responds with reference to the video and the parent)

Reaction time (responds immediately to the content of the video or to reactions from the parent)

Verbal utterances (makes vocalizations, imitates signs, repeats words and utterances, comments with reference to the story, responds to questions from the parent or from the KWS presenter, communicates to parent and asks questions with reference to the story)

Satisfaction (appears to be interested, fascinated, happy).

We reviewed the video recordings on this basis and documented the child’s responses in line with the indicators described by Laevers et al. (Citation2010). We then proceeded to assess the level of involvement in each case, ranging from Level 1 (“no activity”) to Level 5 (“sustained intense activity”). provides a detailed description of each level.

Table 3. The five levels of the Leuven involvement scale

We analyzed the caregiver interviews using qualitative content analysis as set out by Mayring (Citation2015). The choice of qualitative content analysis took place after we had considered the use of grounded theory (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990), but rejected it as not serving our purpose ideally; the grounded theory methodology seeks, in general, to create new theories, while the aim of our study was rather to structure parents’ perceptions of the videos using a clear method of analysis guided by unambiguous rules. Qualitative content analysis, as a method of ascertaining and capture social reality as perceived by individuals, appeared more suitable to us in this context. We aimed at discovering inductive categories that would reveal the mothers’ personal perceptions and experiences of watching the picture book videos. The technique involves seven stages. The first of these involved identifying the unit of analysis; we decided to analyze every complete statement made by the mothers about their experience of using these multimedia-enhanced resources in their day-to-day routines with their children. The second stage of analysis entailed the paraphrasing of content-bearing passages of the interviews. Next, we determined the level of abstraction of a first reduction. By generalizing, in stage four, all utterances referring to the experience of using the resources day to day with the children, we were able to identify and delete paraphrases that duplicated content included elsewhere. Further reduction (stage five) took place via summarizing several statements that resembled one another and occurred repeatedly in the material. The sixth stage consisted in grouping the statements into inductive categories. The following example specifies the procedure as we used it: We reduced and generalized the statement made by Laura’s mother, “The children, both, not only Laura, also her sister,” to the siblings are sharing in the activity, enabling us to assign the statement to the category Bringing family and friends on board. We reduced and generalized the mother’s statement “And then I noticed that he [the father] was also really interested in signing, too. And that also awakened that a bit. I thought that was quite good. And he actually enjoyed doing it” to the father’s interest in KWS was awakened, which we assigned to the same category. The seventh stage of the process involved a final check that sought to ensure the representation of the interviewees’ original utterances within a system of categories (see Results) which emerged through participating parents’ descriptions of their experience with the use of the videos.

Results

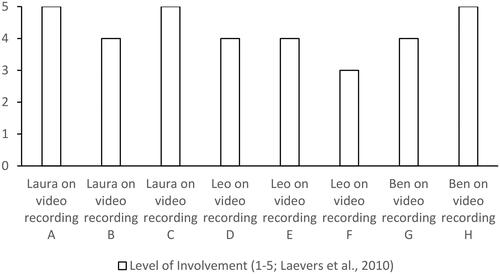

We first detail the results from the eight observational video recordings, using the Leuven Involvement Scale (Laevers et al., Citation2010) for analysis, and follow this with the findings of the three interviews.

Analysis of the video recordings of children’s involvement

summarizes key findings from the analysis of children’s involvement as documented in the video recordings. In the eight situations recorded, we identified three levels of involvement in total. We observed participation with “intense moments” (Level 4) in three of the video recordings and “sustained intense activity” (Level 5) in four. A medium level of involvement occurred in only one video recording, in which we found exclusively “continuous activity without intensity” (Level 3; Laevers et al., Citation2010); in all other cases, the involvement recorded was at Levels 4 and 5. The section that follows describes instances of the three different levels of involvement we detected across the eight video recordings. We explain our assessment of the level of involvement in each case, drawing on the observations from the video recordings and their correlation with the characteristics of the relevant level on the Leuven Involvement Scale as set out in . Our intent is for these three excerpts from the analysis to demonstrate a broad range of children’s interaction and engagement with the videos and illuminate criteria for the assessment of children’s involvement. Words written in capital letters are key word signed.

Continuous activity without intensity (Level 3)

An example of involvement level 3 appeared in Leo’s behavior in video recording F. During the observation, Leo was more or less continuously engaged with the story. He seemed to have little interest in it (3a). He consciously and intentionally followed the story (3c), but needed support from his mother Susanna to maintain his concentration. Leo produced gestures with reference to the story (such as laying his head on his mother’s shoulder and closing his eyes when the story references sleep); imitated signs immediately with reference to the story (e.g., DEAR, GORILLA); repeated statements; answered questions from his mother and the narrator; asked questions about the story. Susanna asked Leo questions, which he later answered, yet in a manner that appeared more routine than eager. Then he became restless on his chair, and his gaze wandered off. When the story was over, he shouted “Finished” loudly, indicating that he wanted the activity to end so he could do something else, although he allowed Susanna to motivate him to continue. Phases of relatively intense activity occurred, but are subject to repeated interruption (3d).

Activity with intense moments (level 4)

An example of involvement level 4 occurred in Laura’s behavior in video recording B: Laura showed intense involvement for at least half of the observation (4a). Some periods of concentration with intense focus were observable, occasionally interrupted by instances of her eyes moving off elsewhere. Laura appeared to be babbling aloud without reference to the story, although she signed with reference to the story, which was why we rated this activity as more routine than intensely involved (4c). Eventually, Laura’s mother, Carolin, became increasingly active in directing her attention to the learning opportunity, making use of prompts and questions and addressing her directly. Laura ended the activity before the story was even complete. We assessed her engagement at level 4 because she showed some intense phases of concentration and high readiness to respond. We further noted a distinct receptivity to interesting stimuli; for example, she grunted when the pig appeared on the screen; pretended to put something in Carolin’s hand when the narrator signed GIFT; signed ANIMAL when presenter asks “What ANIMAL is COMING here?”; moved her body up and down when the kangaroo appeared; raised her hand to her eyes when narrator said “LOOK”. These responses suggested that the activity engaged her to a highly meaningful degree (4b).

Sustained intense activity (Level 5)

An example of involvement level 5 was reflected in Ben’s behavior in video recording H: Ben appeared clearly engrossed in the activity and captivated by the story (5a). His eyes were permanently focused on the video (5b). Only toward the end of the video did his gaze wander once. Ben continuously expressed his motivation through lively and alert responses that make a natural and congruent impression, in keeping with the activity; for instance, he pinched his nose and tried to imitate the sign PIG; vocalized “oh” several times; pointed to the video (5c). Although his expressions and actions repeatedly showed similar patterns (such as the verbal utterance oh and the PIG gesture), these probably represented skills and competencies that were available to Ben at his developmental level. Intense looking and pointing with accompanying sounds revealed some positive energy in Ben (5d).

Analysis of the interviews with mothers

The section that follows describes eight inductive categories that emerged during the qualitative content analysis. In forming these categories, we sought to structure and describe the experiences of mothers.

Category 1: Helping family members become language role models

This category outlines the improvement Carolin, Jennifer, and Susanna noted in their KWS skills via the use of the signed videos, reinforcing their positive attitudes to the use of signing in communication with their children. All mothers considered the use of KWS in day-to-day family life to have increased after taking part in the study. They said they had, on a variety of occasions, tried to use the signs in everyday communication with their children. In addition, Carolin, Jennifer, and Susanna found themselves able to become more effective KWS models by observing the narrator using KWS.

Jennifer: Well, I think it was good and important, not only for my son but also for those of us around him, because we learned a different way of supporting [communication] with facial expressions. Not just the gestures, but also facial expressions to go with them […].

They also noted that the stories encouraged them to model initially inconspicuous and “unimportant” words that they would not otherwise have looked up in a sign dictionary. Jennifer reflected on her experience as follows:

Jennifer: Well, I also learned something new, learned words that I can still use, because I wouldn’t have thought of [them] that way, somehow, because I was busy with EATING and DRINKING, or OUCH, PAIN, such things, or […] it’s always about the little things, and now I always do that in the evening, when we go to bed, I use GOOD NIGHT.

Category 2: Bringing family and friends on board

The signed picture book videos provided an opportunity for the whole family to engage with signing. The children’s siblings could watch along and learn the signs, thus also becoming KWS role models.

Jennifer: And that’s what [Ben’s sister] is already doing when [we watch] Benjamin the Elephant, she has also made ELEPHANT. “Look, an ELEPHANT!” So she’s doing it too. She can already do it better than me. Sometimes I ask her “what was [the sign for] that again?” “Yes mum, [it goes like] this and this”.

The mobile hardware enabled the children to take their stories on visits to others, such as their grandparents, and watch them together. The videos thus increased understanding among those around the children of their communicative situations as child users of AAC, alongside raising awareness of signing as an alternative form of communication.

Category 3: Encouraging the child’s activity

Carolin, Jennifer, and Susanna spoke about perceiving their children as actively engaged in the material. They observed intense listening, imitation of gestures, production of sounds, naming of and commenting on what they saw. The exact types of engagement noted differed according to each child’s individual abilities. Carolin described her daughter’s participation as follows: “So the more we watch it, the more repetition she does, I would say. So that’s where it starts with the animals now. That she also does the LION a bit now. She hasn’t done that before.” Jennifer, commenting on observing her son, noted: “[H]e started to do the things that are easy to do, PIG… well, he held his nose and started grunting and GORILLA he kind of does it like that. But I know what he means and I think that he simply can’t yet perform the other things so well because of his motor skills.”

Category 4: Making learning fun and entertaining

The interviewees considered learning using the picture book videos to have been a fun and entertaining experience for their families. Carolin emphasized the informality of the program and compared it to the entertainment value that TV shows have for children. She perceived a positive learning effect in their use, an effect that effectively emerged alongside the activity rather than being its explicit central focus.

Carolin: It’s not a chore, something you feel you have to do. You can build it into your day and the kids enjoy it. It’s almost like watching television now. That’s great. They love it anyway. And then they learn something in the process. It doesn’t really get any better than that.

Category 5: Setting children’s communication development in motion

The participating mothers’ descriptions of their children’s learning suggested that these audiovisual resources supported the children’s productive and receptive language skills. Carolin described it like this: “FULL and GORILLA. That’s already firmly linked. And that’s pretty cool. Because they’re already really taking it on board a little bit.” Jennifer stated that her child “started doing the [signs] that are easy, PIG, he didn’t, so he held his nose like that and started grunting, and GORILLA. That’s kind of what he does.”

Susanna made more reference than the other mothers to the expansion of her child’s spoken vocabulary, which the resources appear to have stimulated. In her interview, she listed individual words from the stories that her son learned by watching the videos. Susanna noted that it was precisely the multimodal presentation of information in the videos that supported her son’s understanding of the stories: “with the help of the signs, he immediately grasped the story the first time he looked at it.”

Category 6: Easy incorporation into daily routines

The families incorporated the use of the signed picture books into their daily routines according to their children’s needs. The mothers played videos when they observed that their children were in a receptive frame of mind. Jennifer noted that she had chosen to work with the videos at a time of day when she perceived her son “to be ready”, to be “getting calmer” or to have met any need to “let off steam.” Mothers experienced the tablet’s ready availability and portability as a great benefit. Carolin liked the way the family could “take it [the tablet] with [them].”

Category 7: Supportive effects of video design choices

Carolin, Jennifer, and Susanna experienced various design choices in the signed picture book videos as supportive in their children’s learning processes. These included the frequent repetition of words, the adaptation of the level of linguistic input to the child’s abilities, and the real-world quality of the vocabulary included. All mothers considered that the incorporation of the signs into stories helped their children retain as well as learn them, as Carolin pointed out:

Carolin: Through the stories, you just remember it really well. That’s why I have more difficulty with the individual signs [i.e., on their own, outside the context of a story]. Then [I’m thinking] how did that go again, what was that again? And so, when I have the story, I have the story in my head.

Category 8: Disadvantageous video design choices

Carolin, Jennifer, and Susanna named factors relating to the videos that they experienced as deleterious to engagement. They perceived their children as less engaged when they watched the videos too often:

Susanna: If he had watched it too many times in a row. Exactly, then he got impatient and wanted to go straight to the next book or something or wanted to stop completely or do something completely different with the tablet.

Discussion

The high scores attained on the Leuven Involvement Scale during interaction with the videos and the experiences of the participating children’s mothers, as articulated and analyzed in the interviews, indicate that the signed picture book videos developed in this study proved to be a meaningful activity in which parents were able to participate together with their children to develop communication skills. The videos further showed considerable entertainment value and were adaptable to the children’s and families’ individual needs. Our observations suggest that the study’s child participants were largely able to engage intensely and actively with the videos notwithstanding their difficulties, and were also able to take the signs on board and produce them during the video activity. Evidence of this from the observations included exceptionally long attention spans, intense observation of the screen, concentration, joyful facial expressions, upright posture, imitation of signs and gestures, enquiring verbal utterances, and responses to the narrator. Our use of the Leuven Involvement Scale in this context validated its applicability to the analysis of the children’s behavior; the scale enabled us to describe the participants’ receptive behaviors and emotional engagement in a precise and nuanced manner.

The comments made by the participating mothers in the interviews suggest that their experience of watching the signed picture books with their children was positive. They noted that they could incorporate the resources into their families’ daily routines with little extra effort; the videos thus represented an opportunity for them to develop KWS skills alongside their children in an entertaining way that had real significance to their communication.

How participants perceived the videos’ design

We consider the participants’ positive experience with and response to these multimedia resources to be attributable to decisions taken during their planning and design. Some statements made during the interviews are readable as indicators of how we successfully realized the design criteria we had originally identified as significant through our engagement with theories in this area. We categorized the design criteria as follows:

Embedding signing in coherent stories

The incorporation of KWS into the telling of a children’s story enabled an authentic and naturalistic communication context. Children were exposed to KWS at an unconscious level and during an everyday activity which they will have perceived as accessible and motivating. Our findings, in line with those of the study by Frizelle et al. (Citation2023), appear to suggest that KWS embedded in the sharing of books is conducive to a child’s engagement and motivation. The signed picture book videos may represent an opportunity to experience a form of AAC in a real-life context, which Light and McNaughton (Citation2015) cite as an urgent need in the context of AAC interventions.

One participating mother noted that the use of signs embedded in stories enabled her child to retain them more easily than did their disjointed presentation in a dictionary of signs. Our findings are in agreement with those from a longitudinal study by Linebarger and Walker (Citation2005), which posits that a well-structured narrative may aid the learning of vocabulary through audiovisual media.

Informality and immersivity

The immersive concept behind the signed picture book videos we produced meant that the implementation of KWS took place effectively “in the background.” The videos drew on the idea of immersion to create situations that are as similar as possible to those that occur in first language acquisition. Watching videos is error-friendly; no overt correction, admonition, or prompting takes place (Kirch, Citation2008). These factors may have contributed to supporting the children’s involvement. The videos were evidently fun for the children to watch, a characteristic of audiovisual media that research in media education has noted as particularly conducive to learning (Neuß, Citation2012).

An “anytime, anyplace” learning medium

The provision of the picture book videos on tablets made watching independent of spatial and temporal circumstances. Participating mothers were able to decide for themselves when the child appeared likely to be receptive to and engage in the activity. Some of them incorporated the signed picture book videos into daily routines at home, such as their children’s bedtime routine; this practice may result in increased use of KWS. Similarly, Nunes and Hanline (Citation2007) observed effective and positive intervention outcomes when they incorporated a picture communication system, as a form of AAC, into children’s day-to-day home lives.

Putting signs into action beyond the resources; teaching with moving images

Participating mothers experienced observing the videos’ narrator as helpful. The narrator produced the signs in a concrete, specific context, making the practice of KWS directly experiential and real world-centered. The videos therefore showed the mothers how they might use features of a sign that communicated meaning, such as facial expressions, in a manner specific to the context at hand. The signed picture book videos provided the adult with a clear model of signs in action, enabling them to achieve profound understanding of what KWS is, how it can be used, and its potential significance to children who use AAC. In contrast to the findings of other work, that reported parents feeling they did not know enough about AAC systems and noted that this perceived lack of knowledge prevents successful use of AAC (Singh et al., Citation2017), the mothers in our study felt that their knowledge of KWS increased through engaging with the videos.

In one of our three cases, it became evident that the signed video picture books enabled the child’s grandparents and friends to understand the potential of signs in aiding communication with the child. As a result, the mother received increased support from family members when using KWS. This data appears promising in light of the finding by Singh et al. (Citation2017) that a lack of support from wider family can inhibit the use of AAC.

Frequent repetition

Linguists regard repetition and recurrent routines as important factors in successful language acquisition, as they make it easier for children to incorporate stimuli into their own communicative repertoires and participate in daily activities (Aktas, Citation2012). The participating mothers further considered the frequent repetitions in the videos to be helpful for the process of acquiring the signs. Evidently, as shown by their use of signs in the interviews, they were successful in learning signs through the videos with little effort and in incorporating them into their everyday use of language.

Design factors Non-Conducive to engagement and learning

Too much repetition risked a negative effect on involvement if the children watched the signed picture book videos too many times in a row. When sharing books with children, adults can vary their delivery; a video, by contrast, is the same every time. It is evidently not helpful for children to watch a video over and over again; ascertaining an appropriate level of repetition in this context requires further research. An adult may make varied use of the videos by picking up the signs and demonstrating their use in a range of motivating everyday communicative situations.

Although the use of the tablet had some advantages in our setting, provision of the videos in a different format may also be useful. Mothers noted two disadvantages of the tablet: first, the requirement to hold it during the videos, leaving their hands occupied and not free for signing; second, the potential for the device to distract the children from the videos. Showing the videos on a smart TV could ameliorate these issues.

Implications for professional practice

The findings provide illuminating indications for the design of opportunities and resources that aim to promote language development, specifically the acquisition of KWS, in children who use AAC. As well as opening up horizons on what such opportunities and resources might look like, the study’s results underline the conclusions of other work on the importance of access to engaging, needs-based resources for successful use of AAC in its various forms (Dark et al., Citation2019) and the need for well-designed media content for the enhancement of learning (Linebarger & Walker, Citation2005; Wright et al., Citation2001).

In view of the ubiquity of audiovisual and digital media in, and their diverse influence on, day-to-day family life, it would appear sensible to bring together research findings from a range of disciplines when designing new interventions and resources. Our study provides pointers for incorporating KWS into the structures of family life. The videos appear to enable simple and straightforward enrichment of day-to-day environments with natural communicative language opportunities, creating familiarity with what may initially be an unfamiliar form of communication and enabling caregivers in particular to gain a more profound understanding of what KWS is and how it can be used. In thus advancing users’ familiarity with and knowledge of KWS, such resources may help enable child users of AAC to achieve their potential by removing currently existing barriers to its use that arise due to unutilized technical possibilities and inaccurate perceptions of AAC at individual and societal level. Ultimately, as Cologon and Mevawalla (Citation2018) have previously noted, they may be able to promote inclusion. Videos using KWS can improve multimodal access to language and entertainment for children who use AAC. Embedding KWS in picture book videos may also raise the societal profile of alternative forms of communication, increasing their perception as valuable aids to interaction for a range of people, and help create shared communicative situations which are accessible to children with and without language impairments alike.

Limitations and future directions

Our mixed-methods approach permitted us to record in detail the experiences of the participating mothers and children. While the data we collected demonstrates the value of qualitative research findings, one characteristic of the process was the small size of our sample; these findings therefore effectively amount to initial impressions of how families using AAC interacted with the signed picture book videos.

While we experienced participating families as enthusiastic toward the resources, we are aware, due not least to analogous findings in the literature (Kerres, Citation2018), of the possibility that motivation for their use might lessen with time as the novelty wears off. A learner engaging with a new learning medium will show greater enthusiasm initially than later on (De Witt & Czerwionka, Citation2013). Language acquisition depends primarily on constant and diverse experiences and interactions with the language in day-to-day life. Caregivers thus face the challenge of incorporating the information – in this case, the signs – into family life on an ongoing basis.

The fact that, in this study, the same person collected the data and provided the families with professional advice and support on using AAC means that we cannot exclude the possibility of social desirability effects underlying some of the statements participants made in interviews and their expressions of enthusiasm for the resources. This limits the validity of our observations of children’s interest and involvement and of mothers’ statements. This said, we consider the findings on the how of the participants’ interactions with the audiovisual materials to be unaffected by this limitation; this covers areas such as how the children interacted with the videos, relatives coming on board with KWS through the videos’ use, and caregivers incorporating KWS into daily routines.

The great heterogeneity of target groups and the complexity of communication processes supported by multimedia resources are two of the challenges that complicate research into the effectiveness of such resources in acquiring KWS. Nevertheless, this study provides promising indications of the technological potential of digital media in accessible education for individuals with cognitive impairments. Researchers in media didactics posit the helpfulness of flexibly using multimedia resources with target groups that rely on a specific, prepared learning experience (Tulodziecki & Herzig, Citation2004). The signed picture book videos we created could attain a wide reach if they were made available on an internet platform. This availability would contribute significantly to equality of educational opportunity for children with specific educational needs and their families, currently often faced, especially in rural areas, with a lack of educational and therapeutic provision using AAC methods.

A multiple baseline design was beyond the scope of this pilot study. We are therefore unable to determine whether the signed picture book videos are more or less suitable for their purpose than are other interventions. There remains a need for further research to test the benefits of multimedia resources to the process of using KWS. One conceivable approach might consist of a study with a control group setting, with the control group receiving only an electronic sign dictionary rather than picture book videos. Given the benefits of embedding KWS in the sharing of picture books (Frizelle et al., Citation2023), the frequency of children’s and their parents’ signing during book sharing before and after watching the videos may be an illuminating issue to explore.

Conclusion

Our findings show that the signed picture book videos were associated with high levels of involvement among our child participants. We conclude that the videos, with their specific design, positively affected the children’s involvement. Their mothers described their families’ experiences with these videos as having helped them to become language role models, bringing family and friends on board and encouraging the child’s activity. The findings suggest that picture book videos supplemented by KWS and including needs-based design features may be appropriate resources for the implementation of KWS in everyday family life. We therefore surmise that the videos can serve as an activity to aid the establishment of authentic and enjoyable shared communication contexts within families, exposing the interactants to KWS.

We conclude that the videos’ potential for language content comprehension and low-effort, motivated learning of KWS is worth further investigation. Digital media such as television and videos are part of everyday life for most families today. The incorporation of key word signs into family media content may enrich the communicative environment at home in a simple and authentic manner, as well as advancing families’ understanding of what KWS is and how it can be used for communicating with children with complex communication needs.

Acknowledgements

We extend our thanks to the reviewers for their constructive feedback and suggestions on improving the article. Most emphatically, we wish to thank the children and their caregivers for their vital participation in in our study. This contribution has been developed in the project PLan_CV. Within the funding programme FH-Personal, the project PLan_CV (reference number 03FHP109) is funded by the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and Joint Science Conference (GWK).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 All publishers consented to the use of the book for this research in writing or by phone.

2 Two of the videos are accessible at https://www.th-koeln.de/hochschule/mit-der-maus-gebaerden-lernen_78351.php.

3 from METACOM symbols © Annette Kitzinger.

References

- Aktas, M. (2012). Entwicklungsorientierte Sprachdiagnostik und -förderung bei Kindern mit geistiger Behinderung. [Development-centered language diagnostics and support in children with cognitive disabilities]. Elsevier GmbH, Urban & Fischer.

- Anderson, D. R., Bryant, J., Wilder, A., Santomero, A., Williams, M., & Crawley, A. M. (2000). Researching Blue’s Clues: Viewing behavior and impact. Media Psychology, 2(2), 179–194. https://doi.org/10.1207/S1532785XMEP0202_4

- Appelbaum, B. (2016). Gebärden in der Sprach- und Kommunikationsförderung [Signs in language and communication research]. Schulz-Kirchner-Verlag.

- Beukelman, D., & Mirenda, P. (2013). Augmentative and alternative communication: Supporting children and adults with complex communication needs (4th ed.). Brookes Publishing.

- Bosse, I., Schluchter, J.-R., & Zorn, I. (Eds.). (2019). Handbuch Inklusion und Medienbildung [Handbook of inclusion and media education]. Beltz Juventa. Retrieved from https://content-select.com/de/portal/media/view/5c84e9c3-d654-40a6-9304-646eb0dd2d03

- Braun, U. (2000). Keine Angst vor Gebärden [Who’s afraid of signs?]. Unterstützte Kommunikation, 4(2000), 6–11.

- Carle, E. (1987). Die kleine Raupe Nimmersatt [The Very Hungry Caterpillar]. (E. Carle, Illus.). Gerstenberg-Verlag.

- Chazin, K. T., Ledford, J. R., & Pak, N. S. (2021). A systematic review of augmented input interventions and exploratory analysis of moderators. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 30(3), 1210–1223. https://doi.org/10.1044/2020_AJSLP-20-00102

- Clibbens, J. (2001). Signing and lexical development in children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome Research and Practice, 7(3), 101–105. https://doi.org/10.3104/reviews.119

- Cologon, K., & Mevawalla, Z. (2018). Increasing inclusion in early childhood: Key word sign as a communication partner intervention. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 22(8), 902–920. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2017.1412515

- Cruz Leon, M. (2023). Gebärdenlernen mit Bilderbuch-Videos [Learning to sign with picture book videos]. Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-41070-4

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow. The psychology of optimal experience. (1. Aufl.). Harper & Row.

- Dark, L., Brownlie, E., & Bloomberg, K. (2019). Selecting, developing and supporting key word sign vocabularies for children with developmental disabilities. In N. Grove & K. Launonen (Eds.), Manual sign acquisition in children with developmental disabilities (pp. 215–245). Nova Science Publishers.

- De Witt, C., & Czerwionka, T. (2013). Mediendidaktik: Studientexte für Erwachsenenbildung. [Media didactics: Texts for study for adult education] (2nd ed.). Bertelsmann Verlag.

- Fisch, S. M. (2017). Bridging theory and practice: Applying cognitive and educational theory to the design of educational media. In F. C. Blumberg & P. J. Brooks (Eds.), Cognitive development in digital contexts (pp. 217–234). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809481-5.00011-0

- Flick, U. (2011). Das Episodische Interview [The episodic interview]. In G. Oelerich & H. Otto (Eds.), Empirische Forschung und Soziale Arbeit: Ein Studienbuch [Empirical research and social work: A study guide] (pp. 273–280). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

- Flick, U. (2012). Qualitative Forschung. Ein Handbuch [Qualitative research. A handbook]. Rowohlt Verlag.

- Frizelle, P., Allenby, R., Hassett, E., Holland, O., Ryan, E., Dahly, D., & O'Toole, C. (2023). Embedding key word sign prompts in a shared book reading activity: The impact on communication between children with Down syndrome and their parents. International Journal of Language & Communication Disorders, 58(4), 1029–1045. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12842

- Frizelle, P., & Lyons, C. (2022). The development of a core key word signing vocabulary (Lámh) to facilitate communication with children with Down syndrome in the first year of mainstream primary school in Ireland. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md.: 1985), 38(1), 53–66. https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/iaac20 https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2022.2050298

- Glacken, M., Healy, D., Gilrane, U., Gowan, S. H.-M., Dolan, S., Walsh-Gallagher, D., & Jennings, C. (2019). Key word signing: Parents’ experiences of an unaided form of augmentative and alternative communication (Lámh). Journal of Intellectual Disabilities, 23(3), 327–343. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744629518790825

- Goldbart, J., & Marshall, J. (2004). Pushes and Pulls” on the parents of children who use AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 20(4), 194–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434610400010960

- Gola, A. A. H., Mayeux, L., & Naigles, L. R. (2012). Electronic media as incidental language teachers. In D. G. Singer & J. L. Singer (Eds.), Handbook of children and the media (pp. 139–156). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Grimm, H. (1990). Über den Einfluss der Umweltsprache auf die kindliche Sprachentwicklung [On the influence of the language of the child’s environment on children’s language development]. In K. Neumann & M. Charlton (Eds.), Spracherwerb und Mediengebrauch [Language acquisition and the use of media] (pp. 99–112). Gunter Narr Verlag.

- Holler, A., & Schmidt, J. (2010). Wer steigt in die Rakete? Sprachförderung mit der Vorschulsendung JoNaLu [Who’s getting into the rocket? Supporting language with the preschool [television] program JoNaLu. Televizion, 23, 25–28. https://www.br-online.de/jugend/izi/deutsch/publikation/televizion/23_2010_2/Holler_Schmidt-JoNaLu.pdf

- Kaiser, A., & Wright, C. (2013). Enhanced milieu teaching: Incorporating AAC into naturalistic teaching with young children and their partners. Perspectives on Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 22(1), 37–50. https://doi.org/10.1044/aac22.1.37

- Kent-Walsh, J., Murza, K. A., Malani, M. D., & Binger, C. (2015). Effects of communication partner instruction on the communication of individuals using AAC: A meta-analysis. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md.: 1985), 31(4), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2015.1052153

- Kerres, M. (2018). Konzeption und Entwicklung digitaler Lernangebote [Design and development of digital learning programs and resources]. De Gruyter.

- Kirch, M. (2008). Sprachenlernen mit dem Fernsehen. Können Programme das Lernen einer zusätzlichen Sprache fördern? [Learning languages with television: Can programs support the learning of an additional language?]. Televizion, 21, 44–47. https://www.br-online.de/jugend/izi/deutsch/publikation/televizion/21_2008_2

- Laevers, F., Declercq, B., & Stanton, F. (2010). Observing involvement: The Kent – Leuven partnership [early years foundation stage]: A video-training pack. CEGO Publishers.

- Launonen, K. (2019). Sign acquisition in Down syndrome: Longitudinal perspectives. In N. Groves & K. Launonen (Eds.), Manual sign acquisition in children with developmental disabilities (pp. 89–114). Nova.

- Lemish, D., & Rice, M. L. (1986). Television as a talking picture book: A prop for language acquisition. Journal of Child Language, 13(2), 251–274. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0305000900008047

- Light, J., & McNaughton, D. (2015). Designing AAC research and intervention to improve outcomes for individuals with complex communication needs. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 31(2), 85–96. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2015.1036458

- Light, J., McNaughton, D., & Caron, J. (2019). New and emerging AAC technology supports for children with complex communication needs and their communication partner: State of the science and future research directions. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 35(1), 26–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2018.1557251

- Linebarger, D. L., & Walker, D. (2005). Infants’ and toddlers’ television viewing and language outcomes. American Behavioral Scientist, 48(5), 624–645. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764204271505

- Loncke, F. T., Campbell, J., England, A. M., & Haley, T. (2006). Multimodality: A basis for augmentative and alternative communication–psycholinguistic, cognitive, and clinical/educational aspects. Disability and Rehabilitation, 28(3), 169–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280500384168

- Maar, P. (1998). Die Maus, die hat Geburtstag heut [Today is the Mouse's Birthday] (P. Maar, Illus.). Oetinger Media GmbH.

- MacRae, C., & Jones, L. (2023). A philosophical reflection on the “Leuven Scale” and young children’s expressions of involvement. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 36(2), 234–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1828650

- Mahoney, G. (1998). Pivotal behavior rating scale (revised). Family Child Learning Center.

- Mandak, K., O'Neill, T., Light, J., & Fosco, G. M. (2017). Bridging the gap from values to actions: A family systems framework for family-centered AAC services. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33(1), 32–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2016.1271453

- Mayring, P. (2015). Qualitative Inhaltsanalyse: Grundlagen und Techniken [Qualitative content analysis: Fundamental aspects and techniques]. Beltz.

- Neuß, N. (2012). Kinder & Medien. Was Erwachsene wissen sollten [Children and media: What adults need to know]. Friedrich Verlag GmbH.

- Nunes, D., & Hanline, M. F. (2007). Enhancing the alternative and augmentative communication use of a child with autism through a parent‐implemented naturalistic intervention. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 54(2), 177–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/10349120701330495

- O'Neill, T., Light, J., & Pope, L. (2018). Effects of interventions that include aided augmentative and alternative communication input on the communication of individuals with complex communication needs: A meta-analysis. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 61(7), 1743–1765. https://doi.org/10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-17-0132

- Pattison, A. E., & Robertson, R. E. (2016). Simultaneous presentation of speech and sign prompts to increase MLU in children with intellectual disability. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 37(3), 141–147. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525740115583633

- Quinn, A. D., Kaiser, A., & Ledford, J. (2020). Teaching preschoolers with down syndrome using augmentative and alternative communication modeling during small group dialogic reading. American Journal of Speech-Language Pathology, 29(1), 80–100. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_ajslp-19-0017

- Rathmann, P. (2006). Gute Nacht, Gorilla [Good Night, Gorilla] (P. Rathmann, Illus.). Moritz-Verlag.

- Rombouts, E., Maes, B., & Zink, I. (2017). Beliefs and habits: Staff experiences with key word signing in special schools and group residential homes. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 33(2), 87–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2017.1301550

- Rowland, C., & Fried-Oken, M. (2010). Communication Matrix: A clinical and research assessment tool targeting children with severe communication disorders. Journal of Pediatric Rehabilitation Medicine, 3(4), 319–329. https://doi.org/10.3233/prm-2010-0144

- Rudolph, A. (2018). Der Einfluss von lautsprachunterstützenden Gebärden auf das Sprachverständnis von Kindern mit Intelligenzminderung - eine explorative Untersuchung [The influence of gestures and signs supporting verbal language on comprehension of language among children with an intellectual disability]. uk & forschung, 8, 13–22.

- Sachse, S., & Boenisch, J. (2009). Kern- und Randvokabular in der Unterstützten Kommunikation: Grundlagen und Anwendung [Core and fringe vocabulary in AAC: Basics and applications]. In ISAAC Germany (Ed.), Handbuch der Unterstützten Kommunikation, Teil 1 [Handbook of augmentative and alternative communication, part 1] (pp. 30–40). Von Loeper.

- Senner, J. E., Post, K. A., Baud, M. R., Patterson, B., Bolin, B., Lopez, J., & Williams, E. (2019). Effects of parent instruction in partner-augmented input on parent and child speech generating device use. Technology and Disability, 31(1-2), 27–38. https://doi.org/10.3233/TAD-190228

- Sennott, S. C., Light, J. C., & McNaughton, D. (2016). AAC modeling intervention research review. Research and Practice for Persons with Severe Disabilities, 41(2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1177/1540796916638822

- Siebert, S., Najemnik, N., & Zorn, I. (2018). Digitale Medien in der Frühpädagogik: Zwischen Ermöglichung und Verhinderung von Teilhabe bei Aktivitäten mit Tablets [Digital media in early years education: Activities with tablet computers promoting or preventing inclusive participation]. Merz Wissenschaft, 62(6), 89–101.

- Singh, J. S., Hussein, H. N., Kamal, R. M., & Hassan, F. H. (2017). Reflections of Malaysian parents of children with developmental disabilities on their experiences with AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication (Baltimore, Md.: 1985), 33(2), 110–120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434618.2017.1309457

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. M. (1990). Basics of qualitative research: Grounded theory procedures and techniques. Sage Publications.

- Tan, X. Y., Trembath, D., Bloomberg, K., Iacono, T., & Caithness, T. (2014). Acquisition and generalization of key word signing by three children with autism. Developmental Neurorehabilitation, 17(2), 125–136. https://doi.org/10.3109/17518423.2013.863236

- Tulodziecki, G., & Herzig, B. (2004). Handbuch Medienpädagogik: Mediendidaktik [Handbook of media pedagogy: Media didactics]. kopaed.

- Vandereet, J., Maes, B., Lembrechts, D., & Zink, I. (2011). Expressive vocabulary acquisition in children with intellectual disability: Speech or manual signs? Journal of Intellectual & Developmental Disability, 36(2), 91–104. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668250.2011.572547

- Wagner, S., & Sarimski, K. (2012). Entwicklung des Wortschatzes für Gebärden und Worte bei Kindern mit Down-Syndrom im Verlauf [Development of sign and verbal vocabulary over time in children with Down Syndrome]. Uk & forschung, 2, 19–22.

- Wright, J. C., Huston, A. C., Murphy, K. C., St. Peters, M., Piñon, M., Scantlin, R., & Kotler, J. (2001). The relations of early television viewing to school readiness and vocabulary of children from low-income families: The early window project. Child Development, 72(5), 1347–1366. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.T01-1-00352

- Wright, C. A., Kaiser, A. P., Reikowsky, D. I., & Roberts, M. Y. (2013). Effects of a naturalistic sign intervention on expressive language of toddlers with Down syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research: JSLHR, 56(3), 994–1008. https://doi.org/10.1044/1092-4388(2012/12-0060)

- Zorn, I. (2014). Selbst-, Welt- und Technologieverhältnisse im Umgang mit Digitalen Medien [Relationships with the self, the world, and technology in interaction with digital media]. In W. Marotzki, N. Meder, D. M. Meister, & U. Sander (Eds.), Medienbildung und Gesellschaft: Perspektiven der Medienbildung. [Media education and society: Perspectives from media education] (pp. 91–120). Springer VS.

- Zorn, I. (2018). Kommunikation und Lernprozesse beim Einsatz Digitaler Medien in Lernkontexten [Communication and processes of learning in the use of digital media in learning contexts]. In I. C. Vogel (Eds.), Kommunikation in der Schule [Communication in schools] (2nd ed., pp. 177–201). UTB; Klinkhardt, Julius.