Abstract

Background: Universities are at risk for COVID-19 and Fall semester begins in August 2020 for most campuses in the United States. The Southern States, including Mississippi, are experiencing a high incidence of COVID-19. Aims: The objective of this study is to model the impact of face masks and hybrid learning on the COVID-19 epidemic on Mississippi State University (MSU) campus. Methods: We used an age structured deterministic mathematical model of COVID-19 transmission within the MSU campus population, accounting for asymptomatic transmission. We modeled facemasks for the campus population at varying proportions of mask use and effectiveness, and Hyflex model of partial online learning with reduction of people on campus. Results: Facemasks can substantially reduce cases and deaths, even with modest effectiveness. Even 20% uptake of masks will halve the epidemic size. Facemasks combined with Hyflex reduces epidemic size even more. Conclusions: Universal use of face masks and reducing the number of people on campus may allow safer universities reopening.

Article summary line

Scenario analysis for the spread of COVID-19 on US university campuses subject to various intervention methods.

1. Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has affected the United States severely, with nearly three million cases and over 130,000 deaths by July 2020.Citation1 Universities have been using remote learning but are now looking at opening campuses in the Fall Semester and resuming campus activities. This poses a challenge in terms of appropriate infection control measures to ensure the safe re-opening of campuses. The options available are physical distancing, use of hand sanitizer and face covering of any kind. Reduction in the number of people on campus at any one time by use of online or hybrid learning may also be effective as a form of physical distancing by reducing opportunities for person-to-person contact.Citation2 For students on campus, physical distancing may be difficult in classrooms and lecture auditoriums, and the compliance with social distancing may be age dependent.Citation3 One study showed that the lowest compliance with physical distancing was in people aged 18-30 years, with only 52% compliance.Citation3 The number of students on university campuses, in general, can vary from 10,000 to 100,000 or more, and universities are looking to re-open in the fall semester on August 17th 2020.

Mississippi State University (MSU) has nearly 20,000 students, from Mississippi and neighboring states. The majority of students are aged 20-30 years, and there are nearly 6000 faculty and staff. There has been no face to face teaching on campus since March 18th. The state of Mississippi has had more than 33,000 cases and 1,200 deaths as of July 10 2020. The peak incidence of infection in the state is in people aged 18-29 years, with hospitalizations peaking in the 60-69 age group.Citation4

Options for safer re-opening of campuses include HyFlex learning, physical distancing, hand sanitizer and face masks. The hybrid flexible, or HyFlex, course format is an instructional approach that combines face-to-face (F2F) and online learning. Each class session and learning activity is offered in-person, synchronously online, and asynchronously online. Students can decide how to participate. Surgical masks or well-made cloth masks have been shown to be 67% effective against beta coronaviruses such as SARS, MERS CoV and SARS-COV-2.Citation5 However, poor quality cloth masks have low or no efficacy.Citation6 There is also concern that transmission of SARS-COV-2 may be aerosol-borne , with outbreaks described during choral singing and church groups.Citation7 Indoor settings with poor ventilation may also pose a higher aerosol transmission risk.Citation8 The use of face masks during the COVID-19 pandemic has not been evaluated in the setting of a university campus, where the age structure is young and crowded conditions may be present in residential facilities and classrooms.

The aims of this study were to evaluate the impact of face masks and reduced numbers of people on campus on the transmission of SARS-COV-2 at Mississippi State University in order to inform reopening and safer return to the campus for all stakeholders (students, parents, staff and physicians).

2. Methods

A mathematical model of SARS-CoV-2 transmission was developed for Mississippi State University (MSU), with a population of 25,287 people, comprising 19,312 students and 5,976 staff/faculty. The model incorporated standard disease control measures that would normally occur, such as case isolation, contact tracing, and quarantine of contacts. Most students (64%) are from within the state of Mississippi, with another 17% from Alabama, Tennessee, Louisiana and Arkanas. The population of the campus is 0.83% of the 2.97 million residents of the state. The MSU campus population is 25,287 people, and the age structure of the student and staff population is shown in Appendix Table A1.

We used an age-structured deterministic model, with 12 mutually exclusive compartments: susceptible (S), Latent, not infectious (E), Pre-symptomatic infectious and diagnosed (Et), Pre-symptomatic infectious and undiagnosed (Eu), Symptomatic, high infectiousness, diagnosed (I1) and undiagnosed (I2), asymptomatic, high infectiousness (A1), Symptomatic, lower infectiousness, diagnosed (I11) and undiagnosed (I22), Asymptomatic low infectiousness (A2), Recovered (R) and COVID-19 deceased people (D). The varying levels of infectiousness was parametrized using longitudinal data on viral shedding from He et al, which show the peak of infectiousness in the two days prior to symptom onset and the first day of symptoms.Citation9 Each of the compartments is divided into 16 age stratified groups each of 5 years duration, ranging from 0 to 74 years old plus an additional age group of 75+ years.

Given the data are for informing the reopening of campus for the fall semester, we used current disease notification data from July 2020 with a hypothetical campus opening date of July 8th, 2020. The model is simulated for four months starting on July 8th 2020, and we started the epidemic with 6 infected people entering the MSU campus. This was estimated as a proportion of the total daily new notifications in the State two days later (July 10th) of 708, corresponding to the campus population representing 0.83% of the population of the whole state. The cases were distributed in the “latent, not infectious yet” compartment. The rest of the MSU population was considered susceptible. We considered the average latent period to last 5.2 days,Citation10 of which the last two days before symptoms onset are considered infectious.Citation9

In the baseline scenario, using parameters from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and assumed that 35% of cases are asymptomatic.Citation11 We assume transmission is possible from people without symptomsCitation12 and as estimated by the CDC.Citation11 We assumed that 44% of transmissions occur in the last two days of the latent (pre-symptomatic) state in those who develop symptoms.Citation9

Case finding and contact tracing are held as fixed in the model so that the only variation tested is through use of masks and the number of people on campus. We assume 80% of contacts will be traced and quarantined and that this results in a 50% reduction in transmission;Citation13 and 90% of symptomatic cases are isolated after 5 days. Upon infection, a person enters the latent, noninfectious compartment and after 3.2 days will become infectious and may be diagnosed or undiagnosed. When latent people become symptomatic, we assume that the viral load is high the first day and then decreases to lower infectious levels in the following 6 days.Citation9 Symptomatic people will take 1 day to get isolated if they are identified early (such as through contact tracing or outbreak investigation) or 5 days (if they self-present without any active case finding by health authorities) respectively,Citation14 and in this state, once isolated, we assumed zero transmissions. We assumed asymptomatically infected people had equal infectiousness to symptomatic,Citation15 and that 35% of cases asymptomatic or very mild, of which 30% are diagnosed and isolated, and 70% remain undiagnosed.Citation16

Included in the model (outputs not shown) is the transition of infected people to hospitalization or intensive care (ICU) for severe cases and,Citation17,Citation18 in those compartments, people are assumed to not transmit further. Model parameters are shown in Appendix Table A2. Further details of the model (diagram and differential equations) are described in the supplementary material.

In the base case scenario, we tested medical masks, because MSU has procured an adequate stockpile of standard disposable medical masks. The effectiveness of wearing medical masks was assumed to be 67% effective based on a meta-analysis specific to SARS-COV-2, SARS and MERS CoV.Citation5 We assumed 20% effectiveness for a poor quality cloth face covering and 44% a better cloth mask, and 96% for a respirator.Citation5,Citation9,Citation19 We conducted a sensitivity analyses on the effectiveness of mask, which was varied from 20 to 96% to allow for a range of products from poor quality (single layered) cloth face coverings (20%) to N95 respirators (96%).Citation5,Citation9,Citation19 We also did a sensitivity analysis on the proportion of people wearing masks (0, 20, 40, 60 and 80%).

We tested the impact of HyFlex learning methods (part online and part face to face), with a 50% reduction of students and faculty on campus, 20% reduction in social contacts on campus (for example, because physical distancing will be possible in classrooms with fewer people) and 80% wearing a mask.

3. Results

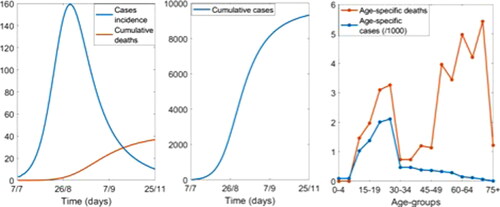

shows the epidemic curve without masks and with standard disease control measures. In this scenario of full campus re-opening, there will be 9,314 cases and 37 deaths by the end of the semester on the 25th November. The epidemic will peak within about 6 weeks of opening. At the peak, there will be 160 new cases a day. While cases are mostly concentrated in people 10 and 34 years old, the death rate is higher in people 50 to 70 years ().

Figure 1. The epidemic curve in the campus population with standard disease control measures but no masks.

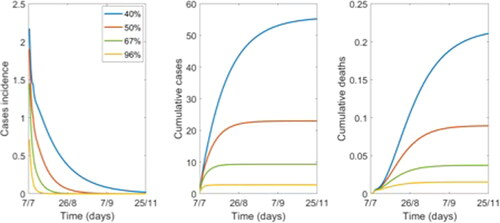

shows the effect of varying the percentage of people on campus wearing a mask. There is a dramatic reduction of cases and almost no deaths if at least 40% of people are wearing a mask () compared to 20% (). However, even at 20% mask use, the cases and deaths are over halved from 9314 cases and 37 deaths (without masks) to 4094 cases and 12 deaths (20% mask use).

Figure 2. Variation in epidemic control by percentage of the population wearing a mask, with 67% efficacy.

Table 1. Variation in epidemic control by percentage of the population wearing a mask, 0-80%.

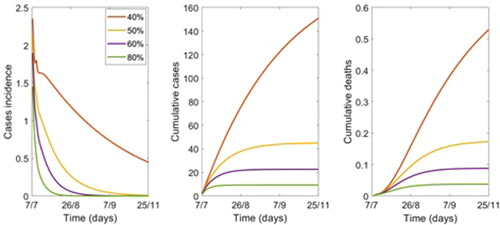

shows the effect of varying mask effectiveness with 80% of people wearing a mask. If at least 80% of people wear a mask, even if only 40% effective, transmission on campus is likely not to result in any deaths (). shows that even a mask of 20% efficacy, if 80% of people are wearing a mask, this more than halves the number of cases and deaths. If the masks are at least 50% effective, the total number of infected could be around 23 people.

Table 2. Variation in epidemic control by effectiveness of masks, with 80% wearing a mask.

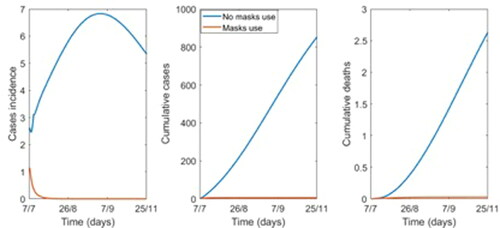

shows the effect of halving the number of people on campus, with and without masks. With no masks, but 50% reduction of people and a 20% reduction in the average number of contacts, using a Hyflex model, there would be 853 cases and 3 deaths by November 25th, compared to 9,314 cases and 37 deaths with full campus opening. Adding mask use for 80% of people will reduce this to six infections and no deaths.

Figure 4. Epidemic curve with a 50% reduction of people on campus, 20% reduction in contact rate, with and without masks (80% wearing, 67% efficacy).

Finally, we tested the sensitivity of the base case scenario results with 80% of people wearing 67% effective masks, when changing the R0 from 2.5 to 1.8 and 3. The results are not very sensitive to the R0 changing if 80% of the population wears masks, indeed with R0 = 1.8, 2.5 and 3 the outbreak will be controlled with 5, 9 and 13 cases respectively and zero deaths (Figure S1 in the supplementary material).

4. Discussion

We showed that universal face mask use on campus, even with masks of lower effectiveness such as cloth masks, will have a substantial impact on COVID-19 transmission on campus if a high proportion of people comply with mask use. There are no randomized controlled trials (RCT) of masks against COVID-19 as yet, but RCTs of masks against other respiratory viruses show efficacy in the protection of well people as well as preventing infected people from onward transmission.Citation19 Masks have also been shown to stop transmission to close contacts in the household, but only if worn by all household members before symptom onset in the index case, confirming the high risk of pre-symptomatic transmission risk.Citation20 One RCT showed that seasonal coronaviruses can be exhaled in normal breathing, but can be completely blocked by the infected person wearing a surgical mask.Citation21 Two infected hair stylists in Missouri, who wore surgical and cloth masks while infected and while serving 139 clients who also used a mixture of cloth and surgical masks, did not infect anyone at the salon.Citation22 This supports the idea that face masks may prevent onward transmission from infected people and also protect well people.

The transmission of COVID-19 may be asymptomatic or occur prior to symptom onset. Outbreak studies show anywhere from 17.9 to 50% of infectious people may be asymptomatic or pre-symptomatic.Citation23–25 As many as 40-45% of infections may be asymptomatic, especially in younger people,Citation16 and a close to half of all transmissions may occur in the two days prior to symptom onset.Citation9 This means that people may be unaware they are infected, and it is not possible to identify all infectious people, especially on a college campus where the majority of the population are young people, who are less likely to be symptomatic.Citation16 Faculty, on the other hand, are older and more at risk of severe disease and complications of COVID-19. For faculty teaching face to face classes, use of masks and physical distancing by students and faculty could reduce the risk of infection transmission.

Blended learning and online learning can also reduce the risk by reducing the number of people on campus at any one time, and by making physical distancing more feasible within closed classroom settings. We showed that this will reduce infection risk, even without masks. However, a combination of reduced people on campus through the Hyflex learning model, along with reduced social contacts on campus and mask wearing would dramatically reduce the infection rate. The HyFlex option essentially reduces the face-to-face interaction time of the classes. These data can inform university administrators to determine to percentage of classes to adopt the online HyFlex or even online model.

Like many other universities, the Fall 2020 semester of Mississippi State is shortened and is planned to end before Thanksgiving. There will be no more class meetings, including examinations, after November 25th. Whilst we did not model this, shortening the semester is also likely to reduce the risk of infection, and this is an additional measure to mitigate risk on campuses.

The limitations of this study include uncertainty about the efficacy of face covering, including cloth masks and face shields, which many people may use. The data for surgical masks was more robust,Citation5 but there is a vast array of different cloth face covering options of untested effectiveness. Furthermore, many trials of masks efficacy are from healthcare settings, which may not be applicable to campus settings, where students may not wear masks for prolonged times. The CDC recommends cloth face coverings in the communityCitation26 and face covering is required in Mississippi State University and the City of Starkville, home to MSU. Although MSU has procured surgical masks, cloth masks may also be used. Some cloth face coverings, such as a bandana or scarf, or even a poorly made cloth mask, may have no or very low effectiveness. The only available RCT of cloth masks showed no efficacy of a 2-layered cotton mask in Vietnamese health workers.Citation6 A face covering of any kind does reduce outward respiratory droplet emissions.Citation27 However, good design principles such as the use of multiple layers, a water-resistant outer layer, good facial fit and daily washing of cloth masks should result in protection.Citation28 The other limitation is that the amount of airborne transmission is unknown,Citation8 and if high, masks may have less effectiveness, as good facial fit and high filtration efficiency (such as with a N95 respirator) are required for airborne pathogens. Nonetheless, the finding from the hair salon in Missouri, that a mixture of cloth and surgical masks prevented transmission, supports the assumptions in our model.Citation22 We also modeled the start of semester from July 10, instead of August 17th, because we wanted to use actual COVID-19 notification data to estimate the number of cases at the start of the modeled epidemic. This was done because we wanted to inform campus opening in a timely way. This results in a slightly longer semester and would over-estimate cases. However, disease incidence is increasing in Mississippi, so if the number of cases in August was much higher than in July, the modeled epidemic would also be larger. Future studies will focus on continuously collecting data related to face covering and infection to update and calibrate the model. The difference between our prediction and the actual numbers will be examined and the potential causes will be investigated. Finally, people may still get infected outside the university campus, and this study only models infections acquired on campus. From an outbreak control perspective, infections arising on campus are important, as they may result in closure of campus and place students and staff at risk. Popular strategies such as untargeted mass testing are less likely to be as cost-effective as mass masking. We also assumed high levels of contact tracing and case finding in the model - during a large epidemic rates may be low, and therefore the need for masks even greater.

In summary, a high level of face mask use on campus by students and staff can enable safer resumption of campus activities. These must be used along with other hygiene measures such as handwashing and physical distancing. Clear instructions on how to make well designed cloth masks will assist in ensuring better effectiveness of cloth face coverings. Risk can be reduced further by use of blended and online learning to reduce the number of people on campus and increase the feasibility of physical distancing.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of Australia and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of University of New South Wales.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (118 KB)Additional information

Funding

References

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report – 171. Available at: https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200323-sitrep-63-covid-19.pdf?sfvrsn=b617302d_2. Published 2020. Accessed May 6, 2020.

- Kucharski AJ, Klepac P, Conlan AJK, et al. Effectiveness of isolation, testing, contact tracing and physical distancing on reducing transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in different settings: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020;20:1151–1160. doi:10.1016/s1473-3099(20)30457-6.

- Moore RC, Lee A, Hancock JT, Halley M, Linos E. Experience with social distancing early in the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States: implications for public health messaging. medRxiv. 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.04.08.20057067.

- Mississippi State Department of Health. COVID-19 in Mississippi. Available at: https://msdh.ms.gov/msdhsite/_static/14,0,420.html#Mississippi. Published 2020. Accessed June 20, 2020.

- Chu DK, Akl EA, Duda S, et al. Physical distancing, face masks, and eye protection to prevent person-to-person transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and COVID-19: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2020;395(10242):1973–1987. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31142-9.

- MacIntyre CR, Seale H, Dung TC, et al. A cluster randomised trial of cloth masks compared with medical masks in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2015;5(4):e006577 doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006577.

- Hamner L, Dubbel P, Capron I, et al. High SARS-CoV-2 attack rate following exposure at a choir practice – Skagit County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(19):606–610. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6919e6.

- Morawska L, Milton DK. It is time to address airborne transmission of COVID-19. Clin Infect Dis. 2020;71:2311–2313. doi:10.1093/cid/ciaa939.

- He X, Lau EHY, Wu P, et al. Temporal dynamics in viral shedding and transmissibility of COVID-19. Nat Med. 2020;6:672–675. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0869-5.

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1199–1207. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2001316.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. COVID-19 pandemic planning scenarios. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/planning-scenarios.html. Published 2020. Accessed July 10, 2020.

- Bai Y, Yao L, Wei T, et al. Presumed asymptomatic carrier transmission of COVID-19. JAMA. 2020;323(14):1406. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.2565.

- Zhang S, Diao M, Yu W, Pei L, Lin Z, Chen D. Estimation of the reproductive number of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) and the probable outbreak size on the Diamond Princess cruise ship: a data-driven analysis. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;93:201–204. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.02.033.

- Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020;323(11):1061. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.1585.

- He D, Zhao S, Lin Q, et al. The relative transmissibility of asymptomatic COVID-19 infections among close contacts. Int J Infect Dis. 2020;94:145–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2020.04.034.

- Oran DP, Topol EJ. Prevalence of Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173(5):362–367. doi:10.7326/M20-3012.

- Garg S, Kim L, Whitaker M, et al. Hospitalization rates and characteristics of patients hospitalized with laboratory-confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 – COVID-NET, 14 States, March 1-30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; 69(15):458–464. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6915e3.

- Richardson S, Hirsch JS, Narasimhan M, et al. Presenting characteristics, comorbidities, and outcomes among 5700 patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the New York City Area. JAMA. 2020;323:2052–2059. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.6775.

- MacIntyre CR, Chughtai AAA. rapid systematic review of the efficacy of face masks and respirators against coronaviruses and other respiratory transmissible viruses for the community, healthcare workers and sick patients. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020; 108:103629. doi:10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2020.103629.

- Wang Y, Tian H, Zhang L, et al. Reduction of secondary transmission of SARS-CoV-2 in households by face mask use, disinfection and social distancing: a cohort study in Beijing, China. BMJ Glob Health. 2020;5(5):e002794. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002794.

- Leung NHL, Chu DKW, Shiu EYC, et al. Respiratory virus shedding in exhaled breath and efficacy of face masks. Nat Med. 2020;26:676–680. doi:10.1038/s41591-020-0843-2.

- Hendrix MJ, Walde C, Findleym K, Trotman R. Absence of apparent transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from two stylists after exposure at a hair salon with a universal face covering policy – Springfield, Missouri, May 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020; ePub: 14 July 2020.

- Mizumoto K, Kagaya K, Zarebski A, Chowell G. Estimating the asymptomatic proportion of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) cases on board the Diamond Princess cruise ship, Yokohama, Japan, 2020 separator commenting unavailable. Eurosurveillance. 2020;25(10):2000180. doi:10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.10.2000180.

- Byambasuren O, Cardona M, Bell K, Clark J, McLaws M-L, Glasziou P. Estimating the extent of asymptomatic COVID-19 and its potential for community transmission: systematic review and meta-analysis. medRxiv. 2020;2020.05.10.20097543.

- Kimball A, Hatfield KM, Arons M, CDC COVID-19 Investigation Team, et al. Asymptomatic and presymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in residents of a long-term care skilled nursing facility – King County, Washington, March 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(13):377–381. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6913e1.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Recommendation regarding the use of cloth face coverings, especially in areas of significant community-based transmission. USA: CDC; 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/prevent-getting-sick/cloth-face-cover.html.

- Bahl P, Bhattacharjee S, de Silva C, et al. Face coverings and mask to minimise droplet dispersion and aerosolisation: a video case study. Thorax. 2020;75(11):1024–1025. doi:10.1136/thoraxjnl-2020-215748.

- Chughtai AA, Seale H, Macintyre CR. Effectiveness of cloth masks for protection against severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26(10):e200948.doi:10.3201/eid2610.200948.