Abstract

Objective

Improve (HPV) vaccination rates in a college-aged population using a strategic toolkit for student health services.

Participants

Eighteen to twenty-six year-olds enrolled at Johns Hopkins University who utilized the Student Health & Wellness Center (JHU SHWC) during the study period.

Methods

The toolkit comprised of a) continuing medical education (CME) presentation on strategies to improve HPV vaccination, b) campus-wide visual messaging regarding HPV prevalence, genital warts, cancer, and vaccine availability, and c) an electronic medical record (EMR) form prompting discussion about the HPV vaccine during visits.

Results

HPV vaccination rates at JHU SHWC improved from historical baseline 290/2,372 students/year (12.2%) to 515/2,479 students/year (20.8%), [risk ratio (RR) 1.70 (95% CI, 1.47–1.96), p < 0.001]. Additional changes included significant increases in vaccination rate per visit and vaccination rate by gender, especially among male students.

Conclusions

Methods and resources from this toolkit could be successfully adapted and deployed by college health centers.

Introduction

To study and write about the HPV vaccine, it is imperative to review its origins, and give attribution to a patient named Henrietta Lacks. In 1951, Dr. Howard Jones examined Lacks at Johns Hopkins Hospital. She had a cervical tumor with an atypical appearance that was biopsied and later cultured in the laboratory. These cells, described as HeLa cells, grew exceptionally well and were the first human cell line to become immortalized in culture.Citation1 In subsequent decades, HeLa cells would aid in the discovery that HPV was responsible for genital warts, cervical cancer, anogenital cancer, and oropharyngeal cancers.Citation2 We must note that these cells were utilized for scientific research without Lacks or her family’s knowledge or permission. Her story highlights not only the importance of informed consent when obtaining and storing biological specimens, but also the systemic racial disparities that persist in medical care and research.Citation3 It is important to honor her legacy and the impact her cells have had on modern medicine, including the discovery that squamous cell cervical carcinoma is entirely attributable to HPV infection, and leading to development of the breakthrough anti-cancer HPV vaccine.Citation4

The most recently published United States Cancer Statistics data (2013–2017) reported 25,405 new HPV-related cancers in females and 19,925 new cancers in males each year.Citation5 HPV remains the most common sexually transmitted infection in the US. Genital HPV prevalence among adults aged 18–59 was 42.5% of the total population, with 45.2% in males and 39.9% in females. Prevalence of oral HPV was 7.3% among adults aged 18–69, 11.5% in males, and 3.3% in females.Citation6

HPV vaccines have been licensed in the US since 2006, and have demonstrated high levels of efficacy and safety.Citation7 The 9-valent HPV (9vHPV) vaccine is currently the only HPV vaccine distributed in the US. It has demonstrated 96.7% efficacy in preventing infection and disease related to HPV subtypes 6, 11, 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.Citation8 The most common adverse events of HPV vaccination in men and women are pain, swelling, erythema, and pruritus at the injection site. Vaccine-related severe adverse events are rare.Citation9

Research has already shown a significant impact of the HPV vaccine in the young adult population. Prior to vaccine introduction (2003–2006) rates of 4vHPV (subtypes 6, 11, 16, and 18) infection in females aged 14 to 19 years were 11.5%, compared to post-vaccine introduction (2009–2012) rates declined to 4.3%. Similarly in females aged 20 to 24 years, pre-vaccine rates of HPV infection went from 18.5%, to post-vaccine rates of 12.1%.Citation10 Among males post-vaccine introduction (2013–2014) one study detected only 1.8% prevalence of 4vHPV type infections in males aged 14 to19 years old, and 4% prevalence in males 20 to 24 years old. This could be related to the direct impact of recommending the vaccine for males in 2011 or the indirect impact of female vaccination.Citation11

To provide potential protection in older age groups, the FDA expanded the approved age range for the HPV vaccine to ages 27–45 years old in October of 2018. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) updated their recommendations in August of 2019 to reiterate that HPV vaccination should be routinely recommended at age 11 or 12 years, and catch-up vaccination should be recommended for all persons through 26 years who were not fully vaccinated. Shared clinical decision-making is advised for adults 27–45 years old, especially for those with risk factors such as new partners, men who have sex with men, transgender persons, and immunocompromised persons.Citation12

Despite the prevalence of HPV and associated cancers, and the existence of a safe and effective vaccine, uptake of the vaccine in the US has not been robust. During 2017–2018, 68.1% of adolescents had ≥1 dose of the HPV vaccine, and the percentage of adolescents up-to-date with the complete HPV vaccine series was 51.1%.Citation13 In 2017, 51.5% of adult females and 21.2% of adult males (19–26 years old) reported receipt of at least one dose of HPV vaccine.Citation14

The barriers to HPV vaccination are multifactorial [].Citation15 Numerous studies have been conducted to address these issues. Information campaigns utilizing marketing materials such as posters, brochures, and public service announcements have been only temporarily successful and insufficient when used alone.Citation16 A systematic review showed that strategies focused on changing behavior by providing tools to make a decision (e.g., message framing, patient reminders, provider reminders) required significant effort, and tended to have inconsistent outcomes.Citation17 Interventions that changed the social environment to facilitate vaccination (e.g., decreased financial barriers, novel vaccination locations, government support), and especially school-based vaccine programs, have been highly effective in other countries, but are not as well accepted in the US.Citation17 Parent-targeted educational interventions had some success for improving HPV vaccination in adolescents (11–17 years old), but are not well studied in the young adult population.Citation18

Table 1. Common barriers to HPV vaccinationTable Footnote*.

It has been well-documented that provider communication techniques can positively influence decision-making. Brief, strong, and presumptive recommendations can improve vaccine uptake.Citation19,Citation20 The “presumptive” or “announcement” approach assumes that the parent/patient will agree to the vaccine as part of routine care, whereas the “participatory” or “conversational” approach conveys that the vaccine is potentially optional and open for discussion.Citation21

Student health centers have a unique opportunity to improve HPV vaccination rates as young adults take control of their own healthcare decisions. One study of undergraduate and graduate student focus groups revealed multiple influences on decision-making, including parental opinions, lack of knowledge about the vaccine, uncertainty around vaccination status, and insurance issues.Citation22 Another study in a university setting tried an intervention with a student-directed marketing campaign (e.g., posters, yard signs, social media posts), this was effective in increasing doses of HPV vaccine given by the health center, but showed a larger impact on female students compared to males.Citation23

Materials & methods

This study was reviewed and approved by the Johns Hopkins Medicine Institutional Review Board (JHM IRB). The aim was to improve HPV immunization rates in a college student population (ages 18–26). The study took place at the Johns Hopkins Student Health & Wellness Center (JHU SHWC) that serves students from two campuses. This population consists of approximately 6,000 undergraduates and 2,500 graduate students. In a typical year, the health center sees approximately 5,000 distinct students and has approximately 15,000 visits. A historical baseline of students who visited the health center (August 15, 2017, through May 31, 2018) would serve as a control group regarding demographics and immunization rates to compare with the group subject to potential interventions (August 15, 2018, through May 31, 2019).

An HPV Campus Vaccination Campaign toolkit was created, focused on HPV vaccination in a college health setting. This was developed after a think tank meeting that convened a panel of experts in HPV and student health to discuss overcoming barriers to HPV vaccination. The toolkit combined several of the interventions that were successful in the scientific literature, including educational materials for patients, EMR prompts, clinician education, and strong presumptive vaccine recommendations. Another goal, if successful, would be sharing effective strategies with other college health centers to serve as a foundation for their local, HPV-specific vaccination efforts. The toolkit consisted of the following components:

Visual messaging

Several forms of visual messaging were placed throughout the Homewood and Peabody campuses of Johns Hopkins University to increase awareness of HPV prevalence and HPV vaccine availability in the JHU SHWC. The following is a sample of the messaging content ():

Figure 1. Sample Brochure.

Reproduced with permission from the HPV Campus Vaccination Program website (https://www.hpv-cvc.org).

If there were a vaccine to prevent genital warts, would you get it?

The HPV vaccine prevents genital warts and certain types of cancer in

both men and women. It provides safe, effective, and lasting

protection against HPV infection.

Call the Student Health & Wellness Center today to get vaccinated against HPV.

The messaging platforms included patient brochures distributed in the waiting rooms and student information packets at the beginning of the academic semester; posters displayed on public access bulletin boards in University-related buildings; eight slide show videos without sound – each about 15–20 seconds in length; yard signs displayed throughout the campuses; and posters inside shuttle buses that travel between the campuses. All awareness materials provided information on HPV and a call to action to contact the JHU SHWC for more information.

Clinician education

All JHU SHWC clinicians (four medical doctors and six nurse practitioners, specializing in Family Medicine and Pediatrics) received a one-hour CME certified training on HPV infection delivered via PowerPoint presentation. The information in this presentation was developed via literature review, and the topics covered included: HPV prevalence, transmission, clinical presentation, vaccination schedules, and strategies to increase vaccination rates as well as answer commonly asked patient questions. The training was followed by a post-test that required a score of 70% or above to obtain 1.0 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit™.

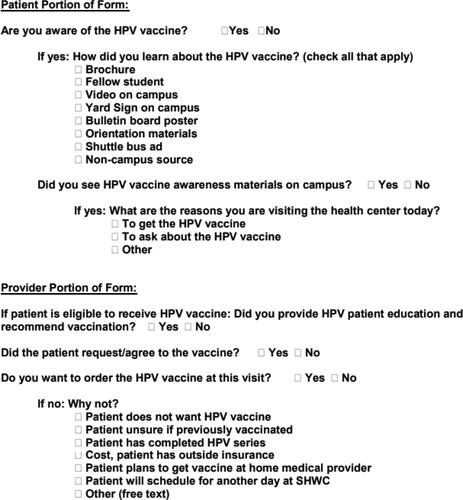

EMR form

We created a customized electronic form in PyraMED P5 ® (a college-health specific EMR platform) that prompted patients to answer some questions about HPV vaccine awareness (). During the study period (August 15, 2018, through May 31, 2019) all distinct patients at JHU SHWC who were 26 years old and younger were prompted to complete this HPV form at self-check-in regardless of their chief complaint or reason for visit. The provider would then review responses with the patient during their visit and complete a provider portion of the form, which included ordering the HPV vaccine if indicated. Prior HPV vaccination records were obtained by patient report, and pre-entrance health data entered in the immunization workplace of P5.

Verbal messaging

Based on the EMR form responses, the provider would determine if the student was eligible for the HPV vaccine. If the patient met eligibility criteria, the provider would give a simple, straightforward, presumptive recommendation for the HPV vaccine. An example would be, “I strongly advise getting the HPV vaccine today because it protects you from a virus that can cause genital warts and cervical, anal or oropharyngeal cancer. This vaccine is safe, effective, and recommended by experts at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and other major medical organizations.”

The vaccine was administered according to ACIP recommendations.Citation12 A three-dose schedule was employed if naive, and a catch-up schedule was employed for those partly immunized. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were in keeping with ACIP recommendations. After confirmation of eligibility and agreement to HPV vaccination by the student, the 9vHPV recombinant vaccine was administered as recommended by the manufacturer. No HPV vaccines were administered for non-FDA approved indications during the study period.Citation24 There was no formal or automatic reminder system for follow up appointments as this was not a feature of our EMR. Students were strongly encouraged to return to the JHU SHWC if they needed additional vaccine doses.

JHU SHWC personnel partnered with EMR staff to obtain the following data from the control and study years: HPV vaccine procurement and administration; the total number of student visits; the number of students who had at least one dose of HPV vaccine; the number of students who had three (or more) doses of the HPV vaccine. In addition, during the study year, HPV EMR form answers were queried to see if students noted awareness campaign materials, and reasons why providers did not give HPV vaccine during visits.

All collected information was kept in a de-identified manner to maintain protected health information (PHI). All comparisons were against historical controls vaccinated by the JHU SHWC in the previous (August 15, 2017, through May 31, 2018) academic year.

The primary outcome variable was the HPV vaccination rate, which was defined as the total number of eligible students per year who received at least one dose of HPV vaccine over the total number of eligible students per inclusion/exclusion criteria. The secondary outcome variables were vaccination rate per visit as a ratio of the total number of vaccinated students over the number of visits within the study period, vaccination rate by gender, and the total number of vaccines purchased and administered. We also looked at patient and provider responses to the HPV EMR form to assess which marketing materials were most effective, as well as the reasons providers did or did not give the HPV vaccination during a visit. Furthermore, we checked the HPV vaccination rates on the two campuses for all students, not just those who visited the health center in the control year. This information was obtained from records submitted during the pre-entrance health form process. Of note, HPV is not one of the required vaccines for admission to JHU.

The vaccination rate during the period of August 15, 2018 – May 31, 2019 (intervention period) was compared with the pre-intervention vaccination rate during the same time in 2017–2018 (control period) using the Poisson regression model with time period as the primary binary predictor. Gender was also considered for statistical adjustment, i.e., intervention vs. control. All tests were two-sided and were conducted at a 0.05 level of statistical significance.

Sample size justification was based on a partial review of historical data and assumed a 10% vaccination rate in the control period. We anticipated that 4,320 patients per academic year time period (i.e., intervention vs. control) would be needed to detect a desired 20% increase in the vaccination rate in the intervention group compared to the control period with 80% statistical power. This effect size was estimated with a statistically significant beta coefficient for the time period in the Poisson regression model, at 0.05 level of statistical significance. The anticipated number of unvaccinated students per year was around 6,400 based on 2016–2017 data. This gave a sufficient sample size, assuming a 30% participation rate per time period. Vaccination rates by time period were also compared separately by sex: male vs. female. With the smallest sample size of 2,800 students per year per time period enrolled, we would be able to detect a 25% increase in the vaccination rate. All statistical analyses were performed with STATA statistical software program (StataCorp. 2015. Stata Statistical Software: Release 14. College Station, TX: StataCorp LP.)

The toolkit was also integrated into a website (https://www.hpv-cvc.org) and subsequently shared with other college health centers via an email to the American College Health Association (ACHA) listserv. As a follow-up to our study, we surveyed the institutions who registered for our website by e-mailing an anonymous survey link. The survey questions were as follows: Did you implement an effort to improve HPV vaccination rates in your student population (yes/no)? What type of effort did you implement (awareness materials, CME presentation, pre-visit patient questionnaire)? If you used the awareness materials provided on the website, which did you use (patient brochure, posters, video slide presentation, yard signs)? Do you have outcomes that you can share (increased vaccination, no change, decreased vaccination, outcomes pending, did not measure outcomes)? How has the COVID-19 pandemic impacted your HPV vaccination efforts (increased, no effect, decreased)? Do you have plans for implementing an effort to improve HPV vaccinations in the future (plan to use awareness materials, CME presentation, pre-visit patient questionnaire, no plans)?

Results

As a baseline, during the control 2017–2018 academic year, 34.6% of all JHU Homewood & Peabody students had records of completing the HPV vaccine series (46% female, 24.1% male). A slightly higher percentage, 46.5% had a history of receiving one or more HPV vaccines (57.9% female, 36.1% male). This is above the national average for adult (age 19–26) HPV vaccination data (in 2017 51.5% of adult females and 21.2% of adult males reported receipt of ≥1 HPV vaccine).Citation14

In the control academic year, 2,372 students would have met eligibility criteria; 1,301 male, and 1,071 female. During the intervention year, 2,479 students met eligibility criteria; 1,372 male, and 1,107 female. Distribution of the number of students by gender was balanced across the two comparison time periods (p = 0.73) ().

Table 2. Gender distribution within the two comparison periods.

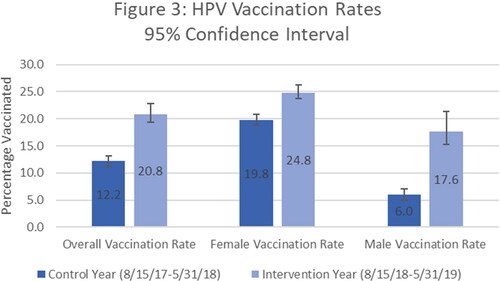

During the control period, 12.2% of students who visited the health center received at least one dose of HPV vaccine vs. 20.8% during the intervention year, yielding a relative rate of 1.70, [95% CI, 1.47–1.96, p < 0.001]. The vaccination rate increase was highest in male students with an almost 3-fold increase (relative rate of 2.93, [95% CI, 2.27–3.78, p < 0.001] ().

The overall vaccination rate per visit increased from 4.4% in the control period to 6.7% in the intervention period, RR 1.54, [95% CI, 1.33–1.77, p < 0.001]. During the study, 888 HPV vaccines were administered vs. 504 in the control period yielding a 76% increase (p < 0.001).

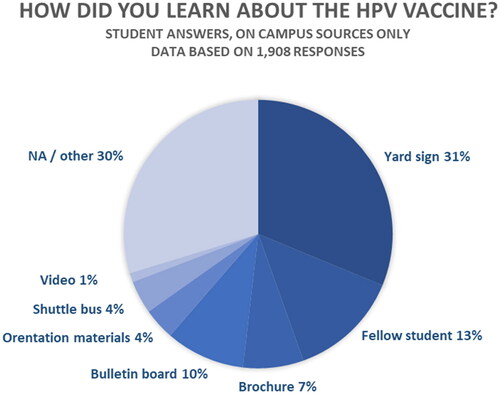

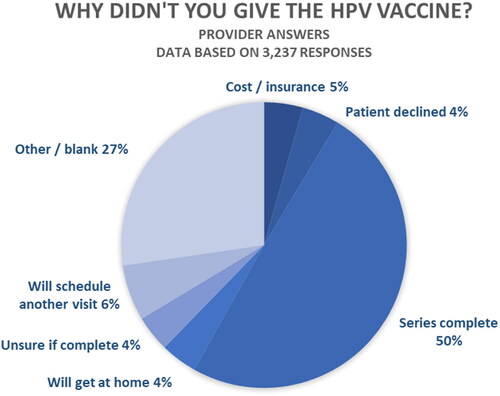

About half of the students who completed the EMR form saw the marketing materials on campus, 1,579 of 3,228 (48.9%) responses. Of all the various marketing materials, the highest number of students noticed the yard signs, 596 responses (18.5%) (). The most frequently cited reason that providers did not give the HPV vaccine during their visit was that the patient already completed the HPV vaccine series, 1,603 responses (49.7%). Only 137 (4%) provider responses reported that patients declined the HPV vaccine ().

To see if our experience with the toolkit was replicated elsewhere, in June 2020 we sent a survey to the 65 institutions that registered for the HPV website. There were 15 respondents (response rate 23.1%), and 13 implemented an effort to improve HPV vaccination rates in their student population (86.7% of respondents). Of the 8 respondents who answered the follow-up questions, most used the awareness materials (87.5%) and pre-visit questionnaire (62.5%), with 2 utilizing the CME presentation (25%). 4 out of 8 (50%) of the institutions reported increased rates/doses of HPV vaccine given as a result of using items from the toolkit. Unfortunately, as this survey was sent in 2020, all 8 respondents acknowledged that the COVID-19 pandemic had an adverse impact on efforts to promote HPV vaccination on campus.

Discussion

This study demonstrates that a well-coordinated campaign with extensive awareness efforts and focused clinical interventions can dramatically impact the rate of HPV vaccinations given on college campuses. Although our sample size was smaller than predicted in our initial justification, the effect was so substantial that we were able to derive highly significant results. The increase was most notable in male students who often cited that they were unaware of HPV consequences or that a provider had never offered them the HPV vaccine in the past. This stands in comparison to another study on a university campus using an awareness campaign which showed a similar 75% increase in doses administered; however, in that study there was a larger increase in uptake for female students.Citation23

Although not a randomized trial, the toolkit component that had the most significant effect leading to immunization was likely the EMR form associated with visit intake that triggered a patient and provider conversation about the HPV vaccine. Such a conclusion may be inferred from the data that shows over half of students (51% who completed the EMR form) did not notice the campaign materials, yet they still agreed to get the vaccine during their visit. This is in alignment with the findings of a large randomized clinical trial of primary care pediatric practices. Intervention practices where clinicians were trained in HPV vaccine communication techniques were less likely to miss opportunities for vaccination (−2.4%), and more likely to initiate the series compared with controls (3.4%).Citation25

Of the marketing materials used, yard signs were the most frequently noticed. The idea to create yard signs stemmed from informal conversations with student groups about ways to deliver information. The students suggested that yard signs stand out from the usual deluge of print and electronic media they consistently receive or fall in their visual fields. A more recent study of qualitative interviews with college students indicates that videos, memes, and infographics would be preferred modalities for HPV information.Citation26

Based on evaluation data and anecdotal comments, the CME presentation to providers was well-received and reinforced their knowledge about the HPV vaccine. Initial provider concerns raised before the study implementation included possible patient delays from filling out extra forms, increased visit time due to additional discussion and administration of HPV vaccine, and fear that patients would be upset talking about HPV when they came to the health center for an unrelated medical issue. However, during the intervention, providers did not notice a significant increase in visit length, and very few patients declined discussion about the vaccine.

The study had several significant limitations. JHU SHWC does not accept insurance other than the Student Health Benefit Plan, which covers vaccines at 100%. Students with different insurance plans would need to pay the entire cost of the immunization out-of-pocket and submit a receipt to their insurance company for reimbursement. As the HPV vaccine poses a significant upfront cost, many students would be unable to pay at the time of service and were concerned that insurance reimbursement was not guaranteed. If the JHU SHWC was able to accept more insurance plans, the effect of the intervention might have been even more significant. Students with outside insurance plans were encouraged to get the HPV vaccine at a pharmacy or their home primary care office where they could utilize insurance; however, we did not reliably receive follow-up information as to whether students followed through with this recommendation.

Another major issue was inaccurate vaccination data obtained from the pre-entrance health form. Many students did not include information about prior HPV vaccination in their health records since this was not a ‘required’ vaccine for admission. Due to incomplete records and patients not remembering their vaccination history, there was uncertainty on the part of patients and providers as to whether they still needed more doses of the HPV vaccine. This was evidenced in the provider portion of the EMR form, in which 50% of the responses stated the reason providers did not give the HPV vaccine during their visit was that the patient reported completion of the HPV series. Therefore, an additional limitation of this study was that there was no system in place to obtain accurate and complete records at the time of each visit. Making the HPV vaccine a mandatory pre-entrance health requirement, or collecting data from state immunization registries may help overcome this challenge.

The EMR also contained other potential inaccuracies and limitations. For example, HPV vaccine history could have been entered erroneously by a student or provider when pre-entrance health records were received. Also challenging, the precise number of enrolled students on campus during the control and intervention periods was somewhat affected by some who were inappropriately ‘inactivated’ in our EMR for various reasons (e.g., prior medical leave of absence, switching from an undergraduate program to graduate program, etc.). This led to them being excluded by the study data design. The EMR also did not have the ability to create automated reminders for students to get subsequent vaccine doses, thus potentially losing some students to follow-up.

Lastly, our EMR does not have detailed race/ethnicity data so we were unable to analyze these important variables. The patient demographic information comes into the EMR as a download from the registrar’s office which limits the information shared. In the race/ethnicity field the only information populated is “Hispanic” or “non-Hispanic” which does not suffice for meaningful analysis. In the future we will explore whether the registrar can share more information on race/ethnicity for study purposes.

Overall, the HPV-directed interventions reinforced the key role college health centers can play in advancing vaccination using a multipronged approach targeting both patients and providers. Improving HPV vaccine acceptance in college-aged adults could even have a downstream effect on HPV vaccination rates for future generations.Citation27 We hope to continue this research, with a greater emphasis on the cancer-prevention message, social media strategies, as well as a closer look at our male student population, and potential systemic barriers to HPV vaccination that may disproportionally affect men. In this era of increasing vaccine hesitancy, we must take every opportunity to educate our patients and increase immunization rates for preventable diseases.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Johns Hopkins Medicine.

To claim CME credit

Visit https://hopkinscme.cloud-cme.com to view CME information and to complete online testing to earn your CME credit.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to: John Gentile and Michael Speidel from Medical Logix, LLC, for assisting with project conceptualization and producing the CME and marketing components. Linda Ziegler and Alexandra Morrel from SHWC for their work on the EMR and clinical implementation of the project. Dana Marks from PyraMED Client Care Services for working on the EMR data collection algorithms. Gayane Yenokyan, PhD from the Biostatistics Consulting Center at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health for conducting the statistical analysis.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Jones HW, Jr. Record of the first physician to see Henrietta Lacks at the Johns Hopkins Hospital: history of the beginning of the HeLa cell line. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;176(6):S227–S228. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(97)70379-X.

- Zur Hausen H. Papillomaviruses in the causation of human cancers—a brief historical account. Virology 2009;384(2):260–265. doi:10.1016/j.virol.2008.11.046.

- Nature Editorial Board. Henrietta Lacks: science must right a historical wrong. Nature 2020;585(7823):7.

- Frazer I. Prevention of cervical cancer through papillomavirus vaccination. Nat Rev Immunol. 2004;4(1):46–54. doi:10.1038/nri1260.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Cancers associated with human papillomavirus, United States—2013–2017. USCS Data Brief, no 18. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/uscs/about/data-briefs/no18-hpv-assoc-cancers-UnitedStates-2013-2017.htm. Published 2020.

- McQuillan G, Kruszon-Moran D, Markowitz LE, et al. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. NCHS Data Brief 2017;(280):1–8.

- Gardasil Vaccine Safety. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/safety-availability-biologics/gardasil-vaccine-safety.

- Joura EA, Giuliano AR, Iversen OE, et al. A 9-valent HPV vaccine against infection and intraepithelial neoplasia in women. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(8):711–723. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1405044.

- Castellsagué X, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men. Vaccine 2015;33(48):6892–6901. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2015.06.088.

- Markowitz LE, Liu G, Hariri S, Steinau M, Dunne EF, Unger ER. Prevalence of HPV after introduction of the vaccination program in the United States. Pediatrics 2016;137(3):e20151968. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-1968.

- Gargano JW, Unger ER, Liu G, et al. Prevalence of genital human papillomavirus in males, United States, 2013-2014. J Infect Dis. 2017;215(7):1070–1079. doi:10.1093/infdis/jix057.

- Meites E, Szilagyi PG, Chesson HW, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination for adults: updated recommendations of the advisory committee on immunization practices. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(32):698–702. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6832a3.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al . National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years—United States, 2018. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2019;68(33):718–723. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6833a2.

- Hung MC, Williams WW, Lu PJ, et al. Vaccination coverage among adults in the United States, National Health Interview Survey. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/imz-managers/coverage/adultvaxview/pubs-resources/NHIS-2017.html. Published 2017.

- Attia AC, Wolf J, Núñez AE. On surmounting the barriers to HPV vaccination: we can do better. Ann Med. 2018;50(3):209–225. doi:10.1080/07853890.2018.1426875.

- Cates JR, Diehl SJ, Crandell JL, et al. Intervention effects from a social marketing campaign to promote HPV vaccination in preteen boys. Vaccine 2014;32(33):4171–4178. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2014.05.044.

- Walling EB, Benzoni N, Dornfeld J, et al. Interventions to improve HPV vaccine uptake: a systematic review. Pediatrics 2016;138(1):e20153863. doi:10.1542/peds.2015-3863.

- Dixon BE, Zimet GD, Xiao S, et al. An educational intervention to improve HPV vaccination: a cluster randomized trial. Pediatrics 2019;143(1):e20181457. doi:10.1542/peds.2018-1457.

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, et al. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics 2017;139(1):e20161764. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764.

- Dempsey AF, O’Leary ST . Human papillomavirus vaccination: narrative review of studies on how providers’ vaccine communication affects attitudes and uptake. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(2S):S23–S27. doi:10.1016/j.acap.2017.09.001.

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics 2013;132(6):1037–1046. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2037.

- Glenn BA, Nonzee NJ, Tieu L, et al. Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination in the transition between adolescence and adulthood. Vaccine 2021;39(25):3435–3444.

- Gerend MA, Murdock C, Grove K. An intervention for increasing HPV vaccination on a university campus. Vaccine 2020;38(4):725–729. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2019.11.028.

- . Gardasil 9. U.S. Food & Drug Administration. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/vaccines-blood-biologics/vaccines/gardasil-9.

- Szilagyi PG, Humiston SG, Stephens-Shields AJ, et al. Effect of training pediatric clinicians in human papillomavirus communication strategies on human papillomavirus vaccination rates: a cluster randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;e210766.

- Koskan A, Cantley A, Li R, Silvestro K, Helitzer D. College students’ digital media preferences for future HPV vaccine campaigns. J Cancer Educ 2021;1–9.

- Robison SG, Osborn AW. The concordance of parent and child immunization. Pediatrics 2017;139(5):e20162883. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-2883.