Abstract

Objective: Chronic pain is a prevalent health issue among young adults; however, there is limited understanding on how it affects university students. This is the first systematic review of evidence relating to the association between chronic pain and psychological, social and academic functioning in university students. Participants: Four databases were searched for relevant published studies. Data from 18 studies including 10,069 university students, of which 2895 reported having chronic pain, were included in the synthesis. Methods: Due to heterogeneity of data and methodologies, meta-analysis was not possible; therefore, data were synthesized narratively. Results: Our findings showed that students with chronic pain have poorer psychological, social and academic functioning and quality of life, compared to students without chronic pain. Conclusions: These findings suggest that chronic pain presents a challenge in university settings. Research is urgently needed to enable an understanding of how universities can support students who experience chronic pain.

Introduction

University students are faced with a variety of challenges and they are often perceived as a distinct population when considering health. Recently, a lot of attention has been given to mental health in students, as psychological difficulties are highly prevalent in this population.Citation1 However, less is known about the impact of physical health, and in particular, chronic pain in university students. Chronic pain is a persistent or reoccurring pain lasting at least 3 months.Citation2 It affects an estimated 20% of people worldwide, and between 13% and 50% of adults in the UK, of which 10.4–14.3% have moderate to severe disabling pain.Citation3,Citation4 These figures are similar in the US, with an estimated 20.4% of adults experiencing chronic pain and a further 8% experiencing high-impact chronic pain.Citation5 Chronic pain conditions lead to a lot of disability and reduced functioning, with chronic low back pain now recognized as the global leading cause of disability and work absence.Citation6,Citation7 Chronic pain is also associated with reduced psychological, social and work functioning in adults, resulting in high health and societal costs.Citation8,Citation9 Research focusing on pediatric chronic pain samples has also shown that pain is associated with higher school absenteeism and poorer peer and social functioning and quality of life.Citation10–12

Several studies have examined prevalence and correlates of health complaints, including pain, in student samples. These studies show that pain is a common problem among university students and is linked to reduced psychological and social functioning and wellbeing.Citation13–15 For example, the annual prevalence of low back pain in university students, one of the most common pain conditions, was found to be around 40% and it was associated with a variety of psychosocial factors.Citation16–18 University students are also reporting high prevalence of chronic pain, with 54% reporting chronic pain of over 3 months in at least one pain site in a recent study.Citation19 Among those students, 19.1% reported chronic pain in at least three pain sites. However, the majority of past research focused on pain prevalence rather than chronic pain and its impact on function in university students.

Examining such relationships is important as university life is marked with heightened stress and psychological distress, which is in turn associated with disability and poorer academic attainment.Citation15,Citation20 Many students are also likely to be inactive, due to studying for long periods of time.Citation21 All in all, university students are faced with a variety of challenges, often associated with the start of independent living and moving away from home. This is also a period commonly associated with being healthy, agile and enjoying oneself, therefore having a chronic health issue such as chronic pain may be perceived as unusual or may even be stigmatized. In a study by Vickerman and Blundell,Citation22 it was found that 25% of students with disability did not want to identify as disabled on their university application due to the fear that they might be rejected a place. There is also some evidence that many university students are reluctant to disclose their disability or chronic illness to their university’s disability services.Citation23

Even though chronic pain is a highly prevalent health issue, which can have a substantial impact on an individual’s functioning and society as a whole, it is insufficiently researched in university settings.Citation24 To our knowledge, this review is the first attempt to provide an understanding of the underlying evidence for the role of chronic pain in university students’ lives, covering a wide range of chronic pain concerns. Specifically, the current review aims to identify, assess and synthesize research evidence relating to the relationship between chronic pain and psychological, social and academic functioning and quality of life in university students.

Methods

Study protocol

This review methodology was guided by a prospectively registered protocol (PROSPERO: CRD42018111890) with a pre-defined search strategy and registered outcomes of interest. The protocol was developed based on guidance from the Center for Review and Dissemination and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (see Supplementary Files).Citation25,Citation26 Minor deviations from this protocol are noted in the study limitations section.

Information sources

We carried out initial searches of four databases (PsycINFO, PubMed/MEDLINE, Scopus and Web of Science), as recommended by the Center for Review and Dissemination.Citation26 After this, we were able to develop a final list of terms ensuring a balance of specificity and sensitivity when completing the final systematic search. The following key words (MeSH and text words) were used: student, pain, chronic pain, functioning, social, academic, psychological, quality of life, wellbeing. The full search string for one database is included in the Supplemental Materials. The four databases were searched from their beginnings to the 3rd of September 2018 and searches were updated on the 6th of March 2021. Additionally, reference list searches of the initially sourced articles were conducted in order to find additional relevant studies.

Study inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if they were empirical and were published in peer-reviewed journals anywhere in the world, in English language, and with no time limits imposed. Both quantitative and qualitative studies were eligible for inclusion.

The population of interest was university students, attending higher education institutions and experiencing chronic pain. Such students are typically aged ≥18 years. Studies were excluded if they focused on primary and secondary school students/pupils. Studies were excluded if pain experiences were related to education specializations and demanding training – for example, physically demanding training such as use of frequent repetitive movements of a particular body part, specific body posture or frequent high stress exposure. This included specific student groups, such as music, athletics, dance, nursing, physical therapy, dental and medical students. There is substantial evidence showing that chronic pain prevalence rates are high among these student groups, associated with the physical demands of the training involved. For example, medical students are typically exposed to high stress and spend more than 7 hours a day sitting down to study,Citation27 while physical therapy students have higher frequency of low back pain than other medical students, which is often linked to bad body posture.Citation28 Studies focusing on these groups often specifically focus on pain associated with the high/specific demands of their training. In order to avoid ambiguity in the interpretation of our findings, studies were also excluded if they did not specifically focus on demanding training. However, if one or more of these groups were part of a larger mixed student sample, a study was included. These specific groups had to comprise less than 50% of the total sample or statistical analysis had to show that they do not differ from other student groups on chronic pain variables. Furthermore, where students were mixed with other populations, such as workers or teachers and their results were not separately analyzed, these studies were excluded.

Chronic pain was our primary variable of interest. Therefore, studies were included if they included participants who reported chronic pain (either primary or secondary chronic pain, according to the International Classification of Diseases-11).Citation29 Chronic primary pain is defined as pain that persists beyond 3 months, causes distress, impairs functioning and cannot be explained by another condition; while chronic secondary pain is described as persistent pain which arises due to other medical conditions.Citation29 Studies were excluded if they solely focused on acute pain. If a study included participants with both acute and chronic pain, it was included if these groups were also analyzed separately and compared.

Studies were excluded if they measured pain prevalence rates or risk factors for developing pain. This is because the main aim of this review was to examine chronic pain in relation to psychological, social and academic functioning and quality of life, as outcome variables. We use the term ‘outcome’ variable tentatively because we anticipate that many included studies will have correlational and/or cross-sectional design. Therefore, our outcome variables of interest were indicators of either psychological, social or academic functioning, as well as quality of life. As chronic pain has been reported to carry adverse effects on psychological, social and occupational functioning and quality of life,Citation30 these outcomes are of particular interest in this population. These variables had to be studied in association with chronic pain variables, such as presence of chronic pain or chronic pain severity. Studies were excluded if they solely measured physical variables (eg, outcomes of physiotherapy, physical activity, physical functioning, body mass index (BMI), sleep, etc.). If a study measured a range of different variables and relationships, results for variables that were not clearly either psychological, social, academic or quality of life were not extracted and included in our synthesis. Finally, if a study used students as a convenience sample and fulfilled all other inclusion criteria, it was included.

Screening of publications

All screening was conducted by three reviewers (DS, CF, RM). Abstracts of all articles were extracted and screened for eligibility by two independent reviewers. Following the initial screening of abstracts, full texts of all included articles were extracted and assessed for eligibility, where at least two reviewers had to agree on the exclusion or inclusion of articles. If necessary, a third reviewer was consulted for a final decision. Deduplication and screening of publications during the first database search was conducted in EPPI Reviewer 4.0.Citation31 Rayyan was used when the search was updated in March 2021.Citation32

Quality assessment of individual studies

Studies were assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal tool.Citation33 shows the assessment questions and whether each study meets each of the criteria. Studies were independently assessed by two reviewers (CF, RM). Disagreements were resolved by consulting a third reviewer (DS), who also assessed a sample of studies to ensure consistency of this processes. We also calculated how many criteria were met by each study; we used these values for guidance only, rather than for excluding studies.

Table 2. Quality assessment of included studies.

Data extraction

Three reviewers (DS, CF, RM) were involved in all stages of data extraction and synthesis. Information from each study was independently extracted by two reviewers and any discrepancies were discussed and resolved with a third reviewer.

The following information was extracted from studies: authors, year of publication, country where the study was conducted, sample size, participants’ sex, age, health issue, pain duration/intensity and university degree, study design, analysis, measured variables (chronic pain and outcome variables relevant to this review) and findings. Findings were extracted narratively (see next section), and they were supported with p values (and effect sizes where available).

Data synthesis

Due to anticipated heterogeneity of data and methodologies, meta-analysis of quantitative evidence was not possible. Consequently, we planned to synthesize evidence narratively. We followed the guidance by the Center for Review and Dissemination which recommend a general narrative synthesis framework consisting of four stages/elements.Citation26 These stages can overlap and do not need to follow this order: (a) developing a theory; (b) developing a preliminary synthesis of findings; (c) exploring relationships within and between studies and (d) assessing the robustness of the synthesis. We decided to group and synthesize extracted findings thematically, according to the variables that were studied in association with chronic pain: psychological functioning variables, social functioning variables, academic functioning variables and quality of life variables. Qualitative studies were planned to be synthesized using a thematic synthesis approach;Citation34 however, since no qualitative studies were identified for inclusion in the synthesis, no further detail is provided here.

Results

Database searching and coding

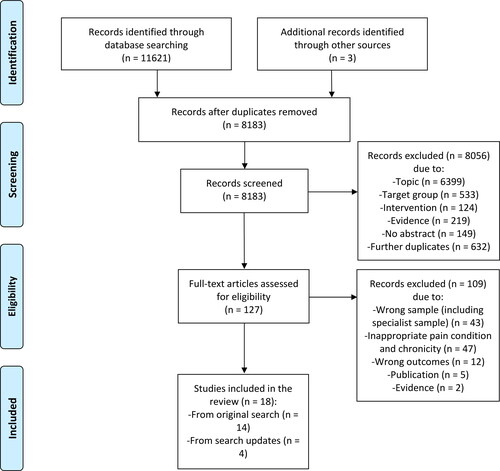

shows the PRISMA flow diagram of the full study selection process conducted for the both the original and updated search; numbers presented in combine searches. It also provides reasons for exclusion. The database searches resulted in identifying 11,621 records; three additional records were identified through hand searching references in eligible records. After deduplicating records; the titles and abstracts of 8183 unique records were screened; 8056 records were excluded at this stage, resulting in a final 127 records for screening at full text. After excluding 109 full-text records, 18 studies were found to be eligible and were included in the final synthesis. All studies were quantitative; no qualitative studies were identified.

Study characteristics

shows study and participant characteristics. In summary, the 18 studies included in the synthesis were published between 1992 and 2020. Studies were published in the United Kingdom (n = 1), Portugal (n = 1), Singapore (n = 1), Turkey (n = 1), Slovenia (n = 1), Japan (n = 1), Brazil (n = 2), Germany (n = 2), China (n = 2), Canada (n = 3) and the United States (n = 3). All studies recruited participants from universities. Six studies collected data online, 10 studies collected data in person, one study did not report their method of data collection, and one study collected data both in person and online. Sixteen studies were cross-sectional and two were longitudinal. All studies used questionnaire design and employed either t test, Chi-square test, MANOVA, ANOVA, correlational or regression analysis, or a combination of these analyses. Three studies included students as convenience sample.Citation35–37

Table 1. Summary of study and participant characteristics of included studies.

Participant characteristics

The 18 studies included 10,069 university students, of which 2895 reported having chronic pain. One study included participants with chronic nonspecific low back pain, one study included participants with chronic musculoskeletal pain, one study included participants with chronic headaches, three studies included participants with Temporomandibular Disorder (TMD), four studies included participants with Irritable Bowel Syndrome (IBS) and eight studies included participants with more than one chronic pain diagnosis or pain location (mixed chronic pain). Thirteen studies used undergraduate students, two of which also included postgraduate students, while two other studies did not specify clearly if any postgraduate students were included. Five studies did not provide information about university degree level. Three studies used psychology students, three studies did not provide information about degree course studied, and the remaining twelve studies included a variety of university degrees. One of these studies had a sample of over 50% of medical students; however, there was no significant difference between them and non-medical students on prevalence of chronic pain, hence this study was included.Citation38 Please see for more information.

Quality assessment

Quality assessment information for all studies is presented in . Five studies met 8/8 criteria, five studies met 7/8 criteria, six studies met 6/8 criteria, one study met 5/8 criteria and one study met 4/8 criteria. In some cases, it was unclear if a criterion was met; this was calculated as not meeting that criterion. No studies were excluded based on quality assessment. All studies satisfied the following criteria: using valid and reliable predictors, using objective and standard criteria for measuring conditions (in this case, pain), assessing outcomes with reliable and valid measures, and applying appropriate statistical methods. Five studies failed to clearly define their inclusion criteria and two studies did not report subjects and study settings in enough detail. Where studies failed most prominently to satisfy criteria was in the reporting of and dealing with confounding factors; seven studies failed to report on potential confounders, while 10 did not take measures to deal with confound variables in their analyses.

Synthesis of evidence

shows how evidence from included studies was synthesized. Results were synthesized narratively and grouped according to the variables that were associated with chronic pain, resulting in four broad categories: (1) psychological functioning; (2) social functioning; (3) academic functioning and (4) quality of life. The majority of studies compared students with chronic pain to those without pain on various psychological, social, academic and quality of life measures. While a small number of studies examined relationships between these variables and pain severity/intensity. Below is a narrative summary of all key findings from .

Table 3. Synthesis of evidence.

Associations with psychological functioning

Several psychological variables were examined across the studies included in the synthesis:

Depression: Results from eight out of nine studies showed that students with chronic pain (mixed chronic pain, TMD, IBS and musculoskeletal chronic pain) had higher levels of depression and that depression was more common among students with chronic pain than in those without, or with infrequent or acute pain.Citation35,Citation38–44 Although, these differences were not found between acute/mild and chronic pain groups in two of these studies.Citation40,Citation42 When measures of depression and anxiety were combined in one of these studies,Citation44 the association between depression and anxiety and presence of TMD was significant.

Anxiety: Results from six out of eight studies showed that students with chronic pain (mixed chronic pain, TMD, nonspecific chronic back pain, IBS and musculoskeletal chronic pain) had higher levels of anxiety or that anxiety was more common than in those without pain.Citation38,Citation40–43,Citation45 Again, this difference was not found between acute and chronic pain in one of these studies.Citation42 Furthermore, state vs. trait-anxiety were found to correlate with the outcomes differently; Pesquiera et al.Citation45 report that the association between TMD presence/severity and trait-anxiety scores was not significant, while the association with state-anxiety was positive and significant.

Mental distress, suicidal indention & meeting criteria for psychiatric disorder: One study found no significant difference in general mental health (a subscale of quality life measure, see below) between students with or without nonspecific chronic low back pain.Citation46 In a second study, suicidal intention was significantly more common in students with IBS than in those without IBS.Citation43 A third study showed significantly elevated values on a mental distress scale and all its subscales (somatization, obsessive–compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity, depression, anxiety, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, psychoticism and hostility) for the IBS group, in comparison to non-IBS group, indicating a generally higher mental strain in those with IBS.Citation47 Finally, a fourth study found that students with IBS were more likely to be diagnosed with a psychiatric disorder (anxiety/depression) than those without IBS.Citation38 The last two studies examined depression and anxiety as part of general mental health assessment; these findings support the depression and anxiety results reported in the previous paragraphs.

Stress: Associations between chronic pain and stress were assessed in four studies, all of which found that students with chronic pain (mixed chronic pain, IBS, chronic headache and TMD) reported higher levels of stress than those without pain.Citation39,Citation40,Citation47,Citation48 One of these studies found a significant difference when comparing students with and without TMD; however, there was not a significant difference between students with mild and moderate TMD.Citation40 In another study, students with IBS reported significantly more stress on eight out of nine stress subscales, many of which related to work and social functioning, so these results to an extent support the social and academic functioning results below.Citation47 Finally, one of these studies specifically focused on the role of daily hassles (defined as a type of stressor), many of which focused on work and social functioning, again supporting our social and academic functioning results below.Citation48

Self-esteem: Associations between pain and self-esteem were assessed by two studies which found that students with chronic pain reported significantly lower levels of self-esteem than those without pain.Citation39,Citation49

The following psychological variables were assessed by one study only:

Perfectionism: Students with chronic headaches reported more self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism than those with non-chronic headaches, but no significant difference was found for other-oriented perfectionism.Citation48 Goal setting: One study found that four out of nine aspects of goal setting (self-efficacy, self-monitoring, self-reward and positive arousal) were significantly lower in students with persistent pain than in those without pain.Citation37 Emotional instability: There were no significant differences in emotional instability reported by students with or without nonspecific chronic low back pain.Citation46 Psychological inflexibility: There were no significant differences in psychological inflexibility between students with chronic pain and those without chronic pain.Citation35 Metacognitions about health: In a sample of students with chronic pain, pain intensity was positively correlated with certain metacognitions about health, including the belief that thoughts are uncontrollable.Citation36

Associations with social functioning

Four studies assessed the relationship between chronic pain and social functioning.Citation36,Citation42,Citation46,Citation50 One study found that students with chronic pain reported lower levels of overall perceived social support than those without pain, as well as perceived family and friends support, however, no significant difference was found for perceived significant other support.Citation42 In the same study, no significant differences were found between students with acute and chronic pain, and between students with acute pain and those without pain on any of these measures. In another study, more pain intensity was correlated with more interference with daily, social and work activities in students with chronic pain.Citation36 A third study found that when comparing chronic health conditions (CHC) that did or did not involve pain; whether or not the CHC involved pain was not associated with social support received from friends or significant others.Citation50 Regarding illness-related support, individuals with CHCs with pain symptomology reported disclosing their CHC status to fewer friends than did those with CHCs without pain; however, pain status was not associated with perceived support following disclosure.Citation50 Finally, a fourth study reported that students with nonspecific chronic low back pain reported significantly poorer social functioning (subscale of a quality of life measure, see below) compared to those without pain.Citation46

Associations with academic functioning

Only two studies assessed the relationship between pain and academic functioning.Citation42,Citation49 One study found that compared to those with non-chronic pain, students with chronic pain reported experiencing significantly higher interferences with schoolwork due to the effects of pain.Citation49 A second study found whether pain was acute or chronic did not predict interference with academic functioning in a sample of students with mixed pain durations.Citation42 However, high levels of pain intensity (regardless of pain being acute or chronic) predicted high levels of interference with academic functioning.Citation42

Associations with quality of life

Three studies found that chronic pain (mixed chronic pain, IBS and nonspecific chronic low back pain) was associated with poorer overall quality of life and several quality of life domains/subscales.Citation46,Citation51,Citation52 A fourth study found a non-significant difference for overall quality of life but it found several significant differences on a number of quality of life domains/subscale; for example, students with chronic pain had more psychological discomfort than those without chronic pain.Citation40

Discussion

We aimed to systematically review and integrate research evidence from studies that examined the relationships between chronic pain and psychological, social and academic functioning and quality of life in university students. The findings were synthesized narratively and indicate that chronic pain is associated with poorer functioning across all studied domains, and that students with chronic pain are faced with greater challenges than those without pain.

Variables that were captured most frequently were depression and anxiety. Higher levels of depression were found in students with chronic pain (compared to students without pain) in all but one study. Interestingly, the only study that did not show a significant difference was published much earlier than the studies that showed significant differences.Citation49 This may suggest that depression has become a more substantial problem in recent years. It might also reflect a shift in public perceptions relating to mental health, and young people’s greater readiness to share their concerns. Similar findings were found for anxiety, where the majority of studies showed that students with chronic pain were more anxious than those without chronic pain. More prominent differences were found between chronic pain and no pain groups, than when comparisons were made between acute/infrequent and chronic pain groups.Citation40,Citation42 However, only a small number of studies made such comparisons, therefore this finding should be interpreted with caution. Overall, findings related to depression and anxiety are supported by past research, which repeatedly finds a positive relationship between chronic pain and depression and anxiety in non-student samples.Citation53–55 Generally, university life is associated with poorer mental health compared to the general population.Citation20 Our findings suggest that this may be more prominent in students who experience chronic pain than those who do not, as indicated by elevated mental distress, suicidal intention and meeting criteria for psychiatric disorder in groups with chronic pain.Citation38,Citation43,Citation47 These findings indicate a higher mental strain on students with IBS specifically and further research is needed to examine this in other chronic pain groups. However, there were no significant differences in emotional instability and psychological inflexibility between students with and without chronic pain.Citation35,Citation46

Students with chronic pain reported higher perfectionism and lower self-esteem.Citation39,Citation48,Citation49 This is supported by research involving non-student populations which found a link between pain and lower self-esteem in adults and between perfectionism and pain in youth.Citation56,Citation57 The association between perfectionism and academic variables has been described as complex, as it can have both a positive and negative relationship with academic attainments.Citation58 Furthermore, several aspects of goal setting were significantly lower in students with chronic pain than in students without pain,Citation37 which may have implications for their academic functioning.

The majority of findings reported in this review indicate that students with chronic pain have significantly poorer quality of life compared to those without pain. These findings are in line with past research showing a relationship between chronic pain and quality of life in both adults and adolescents.Citation10,Citation59 Being at university is also associated with stress,Citation15 for example, stress is considered a leading cause of headaches in university students.Citation60 All studies that examined the relationship between stress and pain in our review found that students with chronic pain had higher levels of stress than those without pain, indicating that chronic pain might bring added pressure to students who experience it. In addition, university students with chronic pain reported more work-related stress and stress relating to social recognition, tension and isolation than students without pain.Citation47 This suggests that providing appropriate support to students with chronic pain within university settings is crucial; this is indicated by the studies which reported significantly lower perceived social support in students with chronic pain compared to those without pain,Citation42 more interference with daily, social and work activities,Citation36 and unwillingness to disclose their pain condition.Citation50 Academic support is also important, as pain is likely to interfere with academic tasks and progress as shown by two studies in this review.Citation42,Citation49 Evidence from studies addressing both adult and adolescent samples support these findings.Citation61,Citation62

Implications for future research and practice

More research is needed to examine the impact of chronic pain on university students’ functioning. Such research is currently scarce, particularly research relating to social and academic functioning. Only a small number of studies included in our review examined this. In comparison, the majority of past research focused on examining pain complaints (regardless of pain duration or chronicity), pain prevalence rates and/or risk factors for developing pain in students. Such studies were excluded from our review as they lacked a clear focus on students who suffer from chronic pain and the impact of this pain on their functioning and quality of life. When such research is conducted, it is important that researchers clearly measure and report their assessment of pain chronicity;Citation63 some studies had to be excluded from this review due to this issue. There is also a need for longitudinal research in this population, in particular the transition from secondary to tertiary education is important to study as it is filled with challenges. More understanding is required on the challenges that students with chronic pain face as they progress through higher education and transition to employment/further education, and how this might hinder their success and affect their wellbeing.

A potential barrier to supporting students with chronic pain at university is their unwillingness to disclose their chronic pain condition. For example, one of the studies included in this review found that students with chronic health conditions and pain symptomology reported disclosing their chronic health status to fewer friends than those that had chronic health conditions without pain symptomology.Citation50 Pain is not commonly associated with young age, therefore social perceptions and stigma may contribute to young people hiding their chronic pain condition from others. Research is needed to examine public attitudes toward chronic pain in young people. University support services may need to encourage these students to come forward and seek support, but currently there is a lack of understanding and clear pathways for detecting students with chronic medical conditions.Citation64 Our findings suggest that students who experience chronic pain may need a diverse support package that would address their psychological, social and academic needs. Research suggests that certain interventions may be helpful in university settings; for example, Firth et al.Citation65 examined the role of mindfulness and self-efficacy in pain perception, stress and academic performance in university students. Their findings suggest that self-efficacy is important for both pain and academic performance, while mindfulness influenced wellbeing and lowered stress. University health services may also consider introducing peer support schemes. Finally, the majority of past research has focused on undergraduate students or mixed groups, more research is needed on postgraduate students who experience chronic pain.

Limitations

This is the first systematic review of evidence focusing on chronic pain in university students and its relationship with their psychological, social and academic functioning and their quality of life. As such, the review helps to provide directions for future research and practice. However, there are some limitations to this review. Due to a diversity of measures used in the included studies and/or insufficient number of studies, a meta-analysis of results was not possible. The majority of studies included in this review were cross-sectional and questionnaire-based studies, this means that the findings should be interpreted with caution and no causal relationships can be inferred. This also means that we were not able to develop a theoretical model based on these findings, which we proposed to do in our pre-registration report. It was also difficult to make meaningful comparisons between different chronic pain conditions because a small number of studies assessed the same chronic pain condition.

A further limitation is that not many studies included participants who reported on a physician-confirmed chronic pain diagnosis; the majority of studies based this on self-report. Moreover, due to a lack of clarity about whether chronic or acute pain was assessed, we excluded several studies that might have provided further evidence on our relationships of interest. However, we believe that our strict inclusion criteria contributed to the clarity of our findings. Our review represents a culturally diverse sample of university students (see ); this of course is an advantage as it contributes to the external validity of our findings. However, higher education systems differ across the world, therefore culture can also be viewed as a potential confound within our synthesis of evidence. Finally, because some outcome variables were assessed by a single study, their findings should be interpreted with caution.

Conclusion

Overall, the findings from this review indicate that students with chronic pain are faced with greater psychological, social and academic challenges and have poorer quality of life, compared to students without chronic pain. These findings are in line with evidence from studies examining non-student populations. They suggest that university students are not protected from experiencing adverse effects of chronic pain due to their youth or agility; this is a misconception that may prevent these students disclosing and discussing their pain experiences openly with others.Citation23 More young people go to university today than ever before and chronic pain is a substantial health issue, yet research on the impact of chronic pain on university students and support they need is lacking. Such research is urgently needed to enable a better understanding and support of this growing population.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of UK.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Mikolajczyk RT, Brzoska P, Maier C, et al. Factors associated with self-rated health status in university students: a cross-sectional study in three European countries. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:215. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-8-215.

- IASP Terminology – IASP. Available at: https://www.iasp-pain.org/Education/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=1698. Accessed March 20, 2021.

- Fayaz A, Croft P, Langford RM, Donaldson LJ, Jones GT. Prevalence of chronic pain in the UK: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population studies. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010364. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010364.

- Macfarlane GJ. The epidemiology of chronic pain. Pain. 2016;157(10):2158–2159. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000676.

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al . Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults – United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6736a2.

- Vos T, Abajobir AA, Abate KH, et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 328 diseases and injuries for 195 countries, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2017;390(10100):1211–1259. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32154-2.

- Lim SS, Vos T, Flaxman AD, et al. A comparative risk assessment of burden of disease and injury attributable to 67 risk factors and risk factor clusters in 21 regions, 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet. 2012;380(9859):2224–2260. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)61766-8.

- Dueñas M, Ojeda B, Salazar A, Mico JA, Failde I. A review of chronic pain impact on patients, their social environment and the health care system. J Pain Res. 2016;9:457–467. doi:10.2147/JPR.S105892.

- Phillips CJ. Economic burden of chronic pain. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2006;6(5):591–601. doi:10.1586/14737167.6.5.591.

- Hunfeld JAM, Perquin CW, Duivenvoorden HJ, et al. Chronic pain and its impact on quality of life in adolescents and their families. J Pediatr Psychol. 2001;26(3):145–153. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/26.3.145.

- Haraldstad K, Sørum R, Eide H, Natvig GK, Helseth S . Pain in children and adolescents: prevalence, impact on daily life, and parents’ perception, a school survey. Scand J Caring Sci. 2011;25(1):27–36. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6712.2010.00785.x.

- Gorodzinsky AY, Hainsworth KR, Weisman SJ. School functioning and chronic pain: a review of methods and measures. J Pediatr Psychol. 2011;36(9):991–1002. doi:10.1093/jpepsy/jsr038.

- Robertson D, Kumbhare D, Nolet P, Srbely J, Newton G. Associations between low back pain and depression and somatization in a Canadian emerging adult population. J Can Chiropr Assoc. 2017;61(2):96–105.

- El Ansari W, Stock C, Snelgrove S, et al. Feeling healthy? A survey of physical and psychological wellbeing of students from seven universities in the UK. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(5):1308–1323. doi:10.3390/ijerph8051308.

- El Ansari W, Oskrochi R, Haghgoo G . Are students’ symptoms and health complaints associated with perceived stress at university? Perspectives from the United Kingdom and Egypt. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(10):9981–10002. doi:10.3390/ijerph111009981.

- Stock C, Mikolajczyk RT, Bilir N, et al. Gender differences in students’ health complaints: a survey in seven countries. J Public Health. 2008;16(5):353–360. doi:10.1007/s10389-007-0173-6.

- Kennedy C, Kassab O, Gilkey D, Linnel S, Morris D. Psychosocial factors and low back pain among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2008;57(2):191–195. doi:10.3200/JACH.57.2.191-196.

- Gilkey DP, Keefe TJ, Peel JL, Kassab OM, Kennedy CA. Risk factors associated with back pain: a cross-sectional study of 963 college students. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2010;33(2):88–95. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2009.12.005.

- Grasdalsmoen M, Engdahl B, Fjeld MK, et al. Physical exercise and chronic pain in university students. PLOS One. 2020;15(6):e0235419. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0235419.

- Stallman HM. Psychological distress in university students: a comparison with general population data. Aust Psychol. 2010;45(4):249–257. doi:10.1080/00050067.2010.482109.

- Felez-Nobrega M, Hillman CH, Dowd KP, Cirera E, Puig-Ribera A . ActivPAL™ determined sedentary behaviour, physical activity and academic achievement in college students. J Sports Sci. 2018;36(20):2311–2316. doi:10.1080/02640414.2018.1451212.

- Vickerman P, Blundell M. Hearing the voices of disabled students in higher education. Disabil Soc. 2010;25(1):21–32. doi:10.1080/09687590903363290.

- Hughes K, Corcoran T, Slee R. Health-inclusive higher education: listening to students with disabilities or chronic illnesses. High Educ Res Dev. 2016;35(3):488–501. doi:10.1080/07294360.2015.1107885.

- Mills SEE, Nicolson KP, Smith BH. Chronic pain: a review of its epidemiology and associated factors in population-based studies. Br J Anaesth. 2019;123(2):e273–e283. doi:10.1016/j.bja.2019.03.023.

- Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group TP, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

- Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). Systematic Reviews: CRD’s Guidance for Undertaking Reviews in Health Care. 3rd ed. Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York; 2009.

- Amelot A, Mathon B, Haddad R, Renault M-C, Duguet A, Steichen O. Low back pain among medical students: a burden and an impact to consider! Spine. 2019;44(19):1390–1395. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000003067.

- Vincent-Onabajo GO, Nweze E, Kachalla Gujba F, et al. Prevalence of low back pain among undergraduate physiotherapy students in Nigeria. Pain Res Treat. 2016;2016:1–4. doi:10.1155/2016/1230384.

- Nicholas M, Vlaeyen JWS, Rief W, et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic primary pain. PAIN. 2019;160(1):28–37. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001390.

- Kawai K, Kawai AT, Wollan P, Yawn BP. Adverse impacts of chronic pain on health-related quality of life, work productivity, depression and anxiety in a community-based study. Fam Pract. 2017;34(6):656–661. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmx034.

- Thomas J, Brunton J, Graziosi S. EPPI-Reviewer 4: Software for Research Synthesis. EPPI-Centre Software. Social Science Research Unit, UCL Institute of Education; 2010.

- Ouzzani M, Hammady H, Fedorowicz Z, Elmagarmid A . Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Syst Rev. 2016;5(1):210. doi:10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4.

- Moola S, Munn Z, Tufanaru C, et al. Chapter 7: Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: Aromataris E, Munn Z, eds. JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. JBI; 2020.

- Thomas J, Harden A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2008;8(1):45. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-8-45.

- Kato T. Effect of psychological inflexibility on depressive symptoms and sleep disturbance among Japanese young women with chronic pain. IJERPH. 2020;17(20):7426. doi:10.3390/ijerph17207426.

- Rachor GS, Penney AM. Exploring metacognitions in health anxiety and chronic pain: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Psychol. 2020;8(1):81. doi:10.1186/s40359-020-00455-9.

- Karoly P, Lecci L. Motivational correlates of self-reported persistent pain in young adults. Clin J Pain. 1997;13(2):104–109. doi:10.1097/00002508-199706000-00004.

- Shen L, Kong H, Hou X. Prevalence of irritable bowel syndrome and its relationship with psychological stress status in Chinese university students. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;24(12):1885–1890. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1746.2009.05943.x.

- Graham JE, Streitel KL. Sleep quality and acute pain severity among young adults with and without chronic pain: the role of biobehavioral factors. J Behav Med. 2010;33(5):335–345. doi:10.1007/s10865-010-9263-y.

- Natu VP, Yap AU-J, Su MH, Ali NMI, Ansari A. Temporomandibular disorder symptoms and their association with quality of life, emotional states and sleep quality in South-East Asian youths. J Oral Rehabil. 2018;45(10):756–763. doi:10.1111/joor.12692.

- Soyuer F, Ünalan D, Elmali F. Musculoskeletal Complaints of University Students and Associated Physical Activity and Psychosocial Factors. 2012;6(1):294–300.

- Serbic D, Zhao J, He J. The role of pain, disability and perceived social support in psychological and academic functioning of university students with pain: an observational study. Int J Adolesc Med Health. 2020.

- Jiang C, Xu Y, Sharma S, et al. Psychosocial factors associated with irritable bowel syndrome development in Chinese college freshmen. J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2019;25(2):233–240. doi:10.5056/jnm18028.

- Minghelli B, Morgado M, Caro T. Association of temporomandibular disorder symptoms with anxiety and depression in Portuguese college students. J Oral Sci. 2014;56(2):127–133. doi:10.2334/josnusd.56.127.

- Pesqueira AA, Zuim PRJ, Monteiro DR, Ribeiro PDP, Garcia AR. Relationship between psychological factors and symptoms of TMD in university undergraduate students. Acta Odontol Latinoam. 2010;23(3):182–187.

- Furtado RNV, Ribeiro LH, de Arruda Abdo B, Descio FJ, Martucci Junior CE, Serruya DC. Nonspecific low back pain in young adults: associated risk factors. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed. 2014;54(5):371–377. doi:10.1016/j.rbr.2014.03.018.

- Gulewitsch MD, Enck P, Schwille-Kiuntke J, Weimer K, Schlarb AA. Mental strain and chronic stress among university students with symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2013;2013:206574. doi:10.1155/2013/206574.

- Bottos S, Dewey D . Perfectionists’ appraisal of daily hassles and chronic headache. Headache J Head Face Pain. 2004;44(8):772–779. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.2004.04144.x.

- Thomas M, Roy R, Cook A, Marykuca S. Chronic pain in college students. Can Fam Physician. 1992;38:2597–2601.

- Feldman ECH, Macaulay T, Tran ST, Miller SA, Buscemi J, Greenley RN. Relationships between disease factors and social support in college students with chronic physical illnesses. Child Health Care. 2020;49(3):267–286. doi:10.1080/02739615.2020.1723100.

- Klemenc-Ketis Z, Kersnik J, Eder K, Colarič D. Factors associated with health-related quality of life among university students. Srp Arh Celok Lek. 2011;139(3–4):197–202. doi:10.2298/sarh1104197k.

- Gulewitsch MD, Enck P, Hautzinger M, Schlarb AA. Irritable bowel syndrome symptoms among German students: prevalence, characteristics, and associations to somatic complaints, sleep, quality of life, and childhood abdominal pain. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(4):311–316. doi:10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283457b1e.

- Serbic D, Pincus T, Fife-Schaw C, Dawson H. Diagnostic uncertainty, guilt, mood, and disability in back pain. Health Psychol. 2016;35(1):50–59. doi:10.1037/hea0000272.

- Pincus T, McCracken LM. Psychological factors and treatment opportunities in low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2013;27(5):625–635. doi:10.1016/j.berh.2013.09.010.

- Linton SJ, Bergbom S. Understanding the link between depression and pain. Scand J Pain. 2011;2(2):47–54. doi:10.1016/j.sjpain.2011.01.005.

- Galvez-Sánchez CMR, del Paso GA, Duschek S. Cognitive impairments in fibromyalgia syndrome: associations with positive and negative affect, alexithymia, pain catastrophizing and self-esteem. Front Psychol. 2018;9:377.

- Randall ET, Smith KR, Kronman CA, Conroy C, Smith AM, Simons LE. Feeling the pressure to be perfect: effect on pain-related distress and dysfunction in youth with chronic pain. J Pain. 2018;19(4):418–429. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2017.11.012.

- Madigan DJ. A meta-analysis of perfectionism and academic achievement. Educ Psychol Rev. 2019;31(4):967–989. doi:10.1007/s10648-019-09484-2.

- Scholich SL, Hallner D, Wittenberg RH, Hasenbring MI, Rusu AC. The relationship between pain, disability, quality of life and cognitive-behavioural factors in chronic back pain. Disabil Rehabil. 2012;34(23):1993–2000. doi:10.3109/09638288.2012.667187.

- Forgays DG, Rzewnicki R, Ober AJ, Forgays DK. Headache in college students: a comparison of four populations. Headache J Head Face Pain. 1993;33(4):182–190. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1993.hed33040182.x.

- Blyth FM, March LM, Nicholas MK, Cousins MJ. Chronic pain, work performance and litigation. Pain. 2003;103(1–2):41–47. doi:10.1016/S0304-3959(02)00380-9.

- Simons LE, Logan DE, Chastain L, Stein M. The relation of social functioning to school impairment among adolescents with chronic pain. Clin J Pain. 2010;26(1):16–22. doi:10.1097/AJP.0b013e3181b511c2.

- Steingrimsdottir ÓA, Landmark T, Macfarlane GJ, Nielsen CS. Defining chronic pain in epidemiological studies: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PAIN .2017;158(11):2092–2107. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001009.

- Lemly DC, Lawlor K, Scherer EA, Kelemen S, Weitzman ER. College health service capacity to support youth with chronic medical conditions. Pediatrics. 2014;134(5):885–891. doi:10.1542/peds.2014-1304.

- Firth AM, Cavallini I, Sütterlin S, Lugo RG. Mindfulness and self-efficacy in pain perception, stress and academic performance. The influence of mindfulness on cognitive processes. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2019;12:565–574. doi:10.2147/PRBM.S206666.