Abstract

Objective: To examine changes in psychological distress of college students as a function of demographic and psychological variables over time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants: Subjects were recruited from a large public university in Northeast Ohio using electronic surveys administered at three time points in 2020. Methods: Demographics, positive psychological metrics (flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience) and psychological distress were collected and a mixed linear model was run to estimate their effect on change in distress. Results: Psychological distress did not change significantly across time. Females experienced more psychological distress than males. Higher levels of flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience were associated with less distress overall. Conclusions: Although psychological distress did not change across observed time, previous data suggests heightened psychological distress that remained elevated across observed time during the COVID-19 pandemic. Positive psychological variables were shown to mitigate psychological distress, and the relationship was stable over time.

Introduction

Coronavirus Disease-19 (COVID-19), a respiratory illness resulting from the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), is responsible for drastic health and lifestyle changes on a global scale. In March 2020, the COVID-19 worldwide pandemic led to many colleges and universities abruptly transitioning in-person courses to online formats. Across the United States, college students vacated campuses and were met with stay-at-home orders designed to create physical separation in order to reduce transmission of COVID-19. Even with these and other similar precautions, the rapid spread of COVID-19 led to very large numbers of positive COVID-19 cases, which continue to grow exponentially each day.Citation1 As of October 2021, there were over 242 million cases globally.Citation2

COVID-19 not only causes physical harm to the virus carrier, but this global, public health event has the potential to lead to psychological distress in the general population as well. Amidst challenges such as varying levels of preparedness in different states, the closing of businesses and schools, and strict social restrictions and quarantine conditions, many have found it psychologically challenging to cope with the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Past research has found social isolation can increase the risk of depression and exacerbate feelings of anxiety.Citation3,Citation4

COVID-19 is not the first global disease that has led to quarantine conditions.Citation5 Past infectious disease outbreaks, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-associated Coronavirus disease (SARS-CoV), Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and influenza A (H1N1) spread through countries leading to quarantines.Citation6–9 The impact of disease related quarantines has been linked to a variety of psychological outcomes. Hawryluck et alCitation10 conducted a community assessment of the psychological effects of being quarantined due to a SARS outbreak in Toronto, Canada. The median quarantine duration for those surveyed was 10 days, and 31.2% of the respondents reported symptoms of depression. Jeong et alCitation11 assessed the mental health status of people in Korea experiencing a two-week quarantine due to contact with a MERS patient. Signs of moderate or greater anxiety were observed in 7.6% of the sample during the quarantine and 3% of the sample four to six months after the quarantine. Wang et alCitation12 investigated the psychological impact of students quarantined for seven days compared to those not quarantined during a mass infection of H1N1 at a college in China. There were no significant differences between the quarantined and not quarantined groups on a measure assessing general state of mental health and being female significantly predicted psychological distress for both groups.

Researchers are currently investigating the psychological impact of being quarantined due to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Filgueiras and Stults-KolehmainenCitation13 assessed adults living in Brazil at the beginning of the COVID-19 quarantine and one month later. Depression and anxiety worsened significantly from time one to time two, and women had significantly higher depression and anxiety scores than men. Zhao et alCitation14 investigated psychological factors among individuals in China, mostly college students, self-isolating due to COVID-19 two weeks during the outbreak. The prevalence rate for mild to severe anxiety and depression were 14.4% and 29.7%, respectively, and older participants reported significantly lower anxiety levels than younger participants. Seventeen days after the first case of COVID-19 was diagnosed in the United Kingdom, Smith et alCitation15 began a study assessing individuals over the age of 18 living in the UK who were self-isolating/social distancing. The study found 36.8% of the sample had poor mental health, and anxiety and depression scores were higher than those reported in past studies. In addition, being female and younger was correlated with poorer mental health. Salman et alCitation16 surveyed students at four Pakistani universities after the country imposed a lockdown and universities were informed to closed. Approximately 34% and 45% of those surveyed reported moderate to severe anxiety and depression, respectively. Compared to older respondents, younger participants reported significantly higher depression scores, and females reported significantly higher anxiety and depression scores than males. The National Center for Health Statistics collected anxiety and depression scores from adults age 18 and older. Of those surveyed in April 2020, the race category with the highest percentage of symptoms for anxiety disorder and depressive disorder (43.95) were people identifying as other/multiple races.Citation17

Research has shown quarantine and social isolation to be associated with increases in psychological distress. However, there appear to be several potential protective factors which may mitigate the risk. Flourishing mental health is a protective factor against anxiety and depression.Citation18 Vidal et alCitation19 administered a flourishing scale to college students and found flourishing was positively associated with improved health outcomes. Another protective factor is social support. Social support is having friends or family that are active in one’s life and can provide information or emotional assistance.Citation20 Li and PengCitation21 surveyed students from a Chinese university during the COVID-19 pandemic and found a significant negative relationship with social support and anxiety. Lechner et alCitation22 found those with increased social support consumed less alcohol during the COVID-19 pandemic, but found that social support did not moderate the relationship between symptoms of psychological distress and increasing alcohol use over time. Resilience has also been shown to be a protective factor. Barzilay et alCitation23 launched a survey through a crowdsourcing research website in the beginning of April 2020. Responses indicated higher resilience scores were negatively correlated with COVID-19 related worry, anxiety, and depression.

The current study aimed to examine changes in psychological distress in college students at a public university in Northeast Ohio across three time points as a function of demographic variables (i.e., race, gender, and class standing) and positive psychological variables (i.e., flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience). These time points overlap with significant events, including campus closure, transition to remote classes, and state-wide stay at home orders and business closures (Time 1: March 2020), about a month into remote learning, quarantine, and closures (Time 2: April 2020), and approximately two weeks after the lifting of stay-at-home orders and the re-opening of many businesses (Time 3: June 2020). Based on the reviewed literature, an elevated level of psychological distress during quarantine periods (Time 1 and Time 2) and a decrease in psychological distress after the quarantine restrictions were lifted (Time 3) were hypothesized. Furthermore, based on previous studies,Citation12–17 Whites and Asians, males, and older students were hypothesized to report less psychological distress than other races, females, and younger students, respectively. Those scoring higher on the protective psychological variables were hypothesized to report less psychological distress than those with lower scores.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 1009 students between the ages of 18 and 77 (mean = 26.0, SD = 8.83) from a large public university in Northeast Ohio. Participants included in the study were those who completed the first three surveys of an ongoing longitudinal study. The majority of the sample was female (79.8%) and White (89.7%). Sample characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of participants (n = 1009) who answered all three surveys.

Procedures

Data for the present analysis was collected at three points in time. In March 2020 (Time 1), approximately two weeks after the university transitioned exclusively to remote learning due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Students enrolled in the spring semester (N = 33,280) were emailed an online baseline survey. A reminder email was sent four days after the initial invitation. As an incentive to complete the survey, participants had the opportunity to win one of six $20 gift cards. A total of 4,276 students (response rate = 12.80%) responded to the Time 1 survey.

Approximately five weeks and ten weeks after the baseline survey, two follow-up surveys (Time 2 and Time 3, respectively) were sent to participants who completed the baseline survey. During the Time 2 survey, many businesses and services were closed (e.g., hair salons, barbershops, in-restaurant dining, fitness centers, sport leagues) and people in the state had been under a stay-at-home order for five weeks.Citation24 Time 3 survey was administered approximately two weeks after the stay-at-home order had been reduced from a state requirement to a strong recommendation. Businesses, such as hair salons, barbershops, and restaurants, had been reopened for about three weeks, and fitness centers and sports leagues had reopened for about two weeks.Citation25,Citation26 Reminder emails were sent three and seven days after the initial invitation for each follow up survey. The surveys were each incentivized with one $100, one $50, and ten $20 gift cards. Time 3 survey offered an additional twenty $10 gift cards. The Time 2 and Time 3 surveys were completed by 1,692 of the 4,276 invited participants (response rate = 39.60%) and 1,552 of the 4,265 invited participants (response rate =36.40%), respectively. The number of participants invited to participate in the Time 3 survey was slightly lower than Time 2 due to participants opting out of the survey during Time 2. For all surveys, participants were informed that their responses would be kept confidential and that the purpose of the study was to assess student wellness during the pandemic. All surveys included questions on depression, anxiety, substance use, perceived social support, and flourishing. The Time 1 survey also included a resiliency scale. While the Time 2 and 3 surveys contained questions pertaining to financial and employment stress as well as social media use. Time 3 included questions assessing the impact of COVID-19.

Measures

Demographics

At Time 1, participants reported their current gender identity. Response options included female, male, trans male/trans man, trans female/trans woman, genderqueer, decline to state, and a write-in option. Due to very small sample sizes for individual categories within transgender, responses were categorized into female, male, and transgender/other. Participants were also asked if they are an international student (yes or no) and whether they are a 100% online student (yes or no). Race, class standing, and GPA for participants were obtained from the University Registrar. Race was collapsed into White, Black/African American, Asian, and Other/Multiracial. Class standing was classified into five categories: Freshman, Sophomore, Junior, Senior, and Graduate.

Flourishing

The Flourishing Scale measures self-perceived success in areas such as relationships, self-esteem, purpose, and optimism.Citation27 Participants utilized a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to respond to 8 statements (e.g., “I lead a purposeful and meaningful life.” and “People respect me.”). The scores were categorized into low (equal to or less than −1 standard deviation from the mean), medium (within + or −1 standard deviation from the mean), and high using (equal to or greater than +1 standard deviations from the mean). With a sample of college students, the Flourishing Scale was found to have high reliabilities and high convergence with comparable measures.Citation28

Perceived social support

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) was used to subjectively assess perception of social support from family, friends, and significant others (e.g., “My family really tries to help me.” and “I can talk about my problems with my friends.”) during all three time points.Citation29 Participants indicated how they currently feel about 12 social support statements using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from “very strongly disagree” to “very strongly agree.” The scores were categorized into low, medium, and high using cutoffs provided by the creators of the scale. The MSPSS has demonstrated very good internal reliability (Cronbach’s coefficient alphas ranging from .84 to .92).Citation30

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS) measures resilience as defined by being able to recover from stress.Citation31 Participants used a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” to indicate their agreement with six statements (e.g., “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times.” and “I tend to take a long time to get over set-backs in my life.”). The scores were categorized into low, medium, and high using cutoffs provided by the creators of the scale. The BRS has been found to have good internal consistency and test-retest reliability.Citation31

Psychological distress

Psychological distress was assessed at all three time points using the four-item Patient Health Questionnaire-4 (PHQ-4).Citation32 The PHQ-4 combines the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (1. Feeling down, depressed, or hopeless. and 2. Little interest or pleasure in doing things.) and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder-2 scales (1. Feeling nervous, anxious, or on edge. and 2. Not being able to stop or control worrying.). At all three time points, participants indicated how bothered they have been by the statements over the past two weeks using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from “not at all” to “nearly every day.” The scores ranged from 0-12 and were placed into the following categories of increasing levels of depression and anxiety severity: normal (0-2), mild (3-5), moderate (6-8), and severe (9-12). The PHQ-4 has been found to be both reliable and valid.Citation32

Statistical analysis

Linear Mixed Modeling with Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) estimation and an unstructured covariance matrix was used to examine the effects of time, demographic variables, and positive psychological variables (i.e., flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience), on symptoms of psychological distress (PHQ-4). We examined changes in PHQ-4 over time as a function of demographic variables in mixed models which included the following independent variables (Model 1) race, time, and the race by time interaction and (Model 2) gender, time, and the gender by time interaction. Each model included the following covariates GPA, international student status, and online student status. Three models examining the effects of time by positive psychological variables used the same independent variable structure and included the scores assessing flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience. Covariates were identical in all models. Due to the exploratory nature of our hypotheses and repeated testing, a Bonferroni correction was applied, with significance set to p = .05/5 = .008.

Results

displays frequencies or means for demographic variables, positive psychological variables, and psychological distress for participants. The majority of participants were female (79.78%), white (89.74%), and domestic students (96.73%), while nearly a quarter (24.4%) of the sample were enrolled in an online program. Participants were distributed fairly evenly across the five class standings with juniors and seniors having slightly less representation. The positive psychological variables were measured at Time 1 and revealed participants, on average, reported high perceived social support and normal levels of resilience and flourishing. The degree of psychological distress remained fairly consistent across the three time points (mean 4.72, SD = 3.35; mean 4.78, SD = 3.35; and mean 4.56, SD = 3.34, respectively).

Bivariate analyses were conducted to establish the independent variables with a statistically significant, unadjusted effect on the dependent variable. The main effects of time on symptoms of psychological distress (PHQ-4) followed by two-way interaction models between time and gender, race, class standing, flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience on ratings of psychological distress across the three time points were examined. None of the two-way interactions with time were statistically significant at p < .008 except resilience. The main effect for time indicated that psychological distress did not change as time progressed (Time 1 to Time 2, b = 0.1, 95% CI −0.24 to 0.35, p = .71; Time 1 to Time 3, b = −0.2, 95% CI −0.46 to 0.13, p = .27).

Linear Mixed Modeling with Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) was used to test five models. Models 1 through 2 examined demographic variables. Model 1 examined the effects of gender and time on psychological distress. The main effect of gender was significant (b = −1.3, 95% CI −1.8 to −0.7, p < .0001), indicating that females experienced more distress overall than males. However, the interaction between gender and time was not significant. There were no significant effects for Model 2 which examined the effects of race and time on psychological distress.

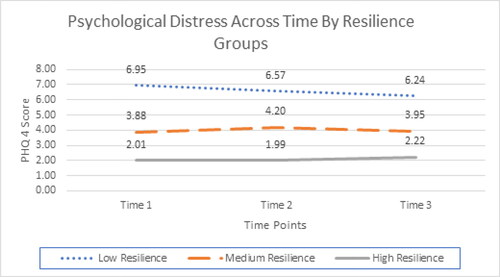

Models 3 through 5 assessed positive psychological variables. Model 3 examined the effects of flourishing and time on psychological distress. The main effect of flourishing was significant indicating that lower flourishing was associated with higher psychological distress overall. Those with a medium flourishing score were, on average, around 2.9 points lower on the psychological distress scale over time compared to those low on the flourishing scale (b = −2.9, 95% CI −3.4 to −2.3, p < .0001). Compared to those who were low on the flourishing scale at baseline, those with a high flourishing score were nearly 5 points lower on the psychological distress scale on average over time (b = −4.9, 95% CI −5.7 to −4.2, p < .0001). The interaction between flourishing and time was not significant. Model 4 examined the effects of perceived social support and time on psychological distress. There was a significant main effect indicating those with higher perceived social support scored, on average, 3.1 points lower on the psychological distress scale over time (b = −3.2, 95% CI −4.4 to −1.98, p < .0001). The interaction between perceived social support and time was not significant. Model 5 examined the effects of resilience and time on psychological distress (). There was a significant main effect indicating those with medium resilience, compared to those with low resilience, had a lower psychological distress score by about 3 points (b = −3.1, 95% CI −3.5 to −2.7, p < .0001). Those with high resilience score nearly 5 points lower on average over time on the psychological distress than those with low resilience over time (b = −5, 95% CI −5.7 to −4.3, p < .0001).

Table 2. Model with adjusted estimates for resilience.

Discussion

On a national and global level, the COVID-19 pandemic created separation, restriction of freedom, and uncertainty surrounding the virus. The objective of the present study was to follow college students across several phases of the pandemic in order to assess psychological distress as well as factors that have been shown to promote psychological well-being. When psychological distress was measured at Time 1 for the current study, news of a worsening pandemic was increasing, and campus closure seemed imminent. Further, classes were moving to a remote format and stay-at-home orders were being enacted. This suggests that psychological distress may have already increased among the participants prior to our Time 1 measurement and the heightened psychological distress continued to be maintained.

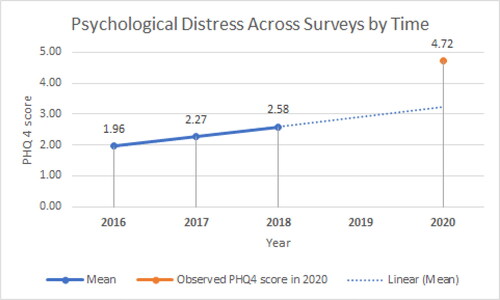

Psychological distress did not significantly change across the three time points of the current study. However, there is evidence of increased levels of psychological distress during the pandemic. In 2016, 2017, and 2018, psychological distress was measured at the participants’ university through a campus-wide survey administered to all enrolled students. To reduce the effects of academic stressors modifying psychological distress, the cross-sectional surveys were active outside of typical midterm and final exam periods. It is likely the majority of those who participated in the current study did not participate in the 2016–2018 survey due to changes in student enrollment status as well as the addition of new students to the sample.

The current participants reported significantly higher levels of psychological distress than in the 2016–2018 surveys when psychological distress was assessed. Using the 2016–2018 data, a linear forecast predicted psychological distress in 2020 to be 3.19; however, the empirical value was 4.72. Both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies examining college students’ mental health reported increases in anxiety and depression during the pandemic.Citation33–35 Therefore, even allowing for the observed upward trend in college students’ psychological distress every year, there is reason to believe the psychological distress reported in the current study is an outlier ().

Figure 1. PHQ-4 scores from years 2016-2018, a linear forecast trendline and the observed value in 2020.

The current study assessed psychological distress in response to the COVID-19 pandemic across three time periods with each time period reflecting a different aspect of the pandemic. As hypothesized, higher levels of flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience were associated with less psychological distress. However, contrary to the hypothesis, psychological distress did not decrease at Time 3 when quarantine restrictions were eased. This may be an indication that the consequences of the pandemic are longer-lasting than the shorter quarantine period. For example, there is potential for financial and/or employment stressors to linger and contribute to psychological distress. Further, future uncertainty about the pandemic may be contributing to elevated levels of distress.

Consistent with past research, regardless of time period, females enrolled in the current study reported higher levels of psychological distress.Citation12,Citation15,Citation36 Psychological distress was assessed by measuring depression and anxiety, and both these mental illnesses have consistently been shown to be more prevalent in females than males. Females are nearly twice as likely to be diagnosed with depression or anxiety than males, and biological, psychosocial, and gender-role hypotheses have been proposed to explain gender differences in psychological distress.Citation37,Citation38 In addition, college students are faced with a variety of potential stressors, such as financial hardships, academic overload, and competition with peers, that may increase psychological distress.Citation39 Females may respond to stressors like these differently than males leading to gender differences in psychological distress.

A significant interaction between resilience and time was observed with a somewhat counterintuitive effect; higher levels of resilience were associated with increased psychological distress over time. An examination of means showed a slight increase in psychological distress between the medium and high resilience groups and a slight decrease in psychological distress in the low resilience group (). However, the high resilience group reported the lowest level of psychological distress across all three time periods followed by the medium resilience group, and then the low resilience group. The increase in psychological distress over time in the high and medium resilience groups could be explained as a regression toward the mean. Another explanation is participants were placed into resilience groups based on Time 1 data. However, researchers acknowledge resilience is context and time specific, and therefore, resilience may have changed across time which could account for the increase in psychological distress for the high and medium resilience groups.Citation40

There are several limitations associated with the current study that should be considered when interpreting the results. Ideally, psychological distress would have been measured prior to the pandemic allowing for a baseline measure to compare changes over time prior to the pandemic and during the pandemic. However, data collected at the university between 2016 and 2018, suggests psychological distress was already elevated by Time 1 and a potential reason why psychological distress did not increase over time. Next, the generalizability of the results is potentially limited due to the sample being comprised of students from one large university. Despite covariation for gender and race, the majority of students at the university are female and white, which further limits generalizability. Furthermore, participants elected to participate in the surveys and reported on their own mental health, which potentially introduce self-selection bias and reporting bias.

Public health implications

The results of the present study suggest elevated levels of psychological distress for college students stemming from the COVID-19 pandemic. However, higher levels of flourishing, perceived social support, and resilience were associated with lower levels of psychological distress. College and university officials should pursue programming and services to increase well-being in these areas with a specific focus on females. Research has recommended institutions allow students to have free time, offer smaller classes with fewer lecture hours, therapy, and increase knowledge and understanding of mental health to reduce or prevent psychological distress in females.Citation41 Mental health screenings can be used to recognize students in psychological distress. A continued exploration of the effects of quarantine are needed in order to further mitigate the negative psychological effects of the pandemic.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States of America and received approval from the Institutional Review Board of Kent State University.

Funding

No funding was used to support this research and/or the preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Barbera RJ, Norris F, Wright JH. Embracing Distancing and Cushioning the Blow to the Economy. Johns Hopkins University & Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center; 2020.

- COVID-19 Dashboard. Available at https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Published 2021.

- Goodman LA, Salyers MP, Mueser KT, et al. Recent victimization in women and men with severe mental illness: Prevalence and correlates. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(4):615–632. doi:10.1023/A:1013026318450.

- Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, et al. Social isolation, loneliness and depression in young adulthood: a behavioural genetic analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2016;51(3):339–348. doi:10.1007/s00127-016-1178-7.

- Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome-associated Coronavirus Disease (SARS-CoV). National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System. Available at https://wwwn.cdc.gov/nndss/conditions/severe-acute-respiratory-syndrome-associated-coronavirus-disease/case-definition/2003/07/. Published 2003.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/mers/about/index.html. Published 2019.

- Tong TR. Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Perspect Med Virol. 2006;16(January):43–95. doi:10.1016/S0168-7069(06)16004-8

- Li X, Geng W, Tian H, Lai D. Was mandatory quarantine necessary in China for controlling the 2009 H1N1 pandemic? Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2013;10(10):4690–4700. doi:10.3390/ijerph10104690.

- Hawryluck L, Gold WL, Robinson S, Pogorski S, Galea S, Styra R. SARS control and psychological effects of quarantine, Toronto, Canada. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(7):1206–1212. doi:10.3201/eid1007.030703.

- Jeong H, Yim HW, Song YJ, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to Middle East Respiratory Syndrome. Epidemiol Health. 2016;38:e2016048. doi:10.4178/epih.e2016048.

- Wang Y, Xu B, Zhao G, Cao R, He X, Fu S. Is quarantine related to immediate negative psychological consequences during the 2009 H1N1 epidemic? Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2011;33(1):75–77. doi:10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2010.11.001.

- Filgueiras A, Stults-Kolehmainen M. Factors linked to changes in mental health outcomes among Brazilians in quarantine due to COVID-19. medRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.05.12.20099374.

- Zhao Y, An Y, Tan X, Li X. Mental Health and Its Influencing Factors among Self-Isolating Ordinary Citizens during the Beginning Epidemic of COVID-19. J Loss Trauma. 2020;25(6-7):580–593. doi:10.1080/15325024.2020.1761592.

- Smith L, Jacob L, Yakkundi A, et al. Correlates of symptoms of anxiety and depression and mental wellbeing associated with COVID-19: a cross-sectional study of UK-based respondents. Psychiatry Res. 2020;291:113138. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113138.

- Salman M, Asif N, Mustafa ZU, et al. Psychological Impact of COVID-19 on Pakistani University Students and How They Are Coping. medRxiv Published online January 1, 2020. doi:10.1101/2020.05.21.20108647.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Anxiety and Depression. National Center for Health Statistics. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/covid19/pulse/mental-health.htm. Published 2020.

- Schotanus-Dijkstra M, Drossaert CHC, Pieterse ME, Boon B, Walburg JA, Bohlmeijer ET. An early intervention to promote well-being and flourishing and reduce anxiety and depression: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interv. 2017;9(April 2016):15–24. doi:10.1016/j.invent.2017.04.002.

- Vidal C, Silverman J, Petrillo EK, Lilly FRW. The health promoting effects of social flourishing in young adults: A broad view on the relevance of social relationships. Soc Sci J. 2020; doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2019.08.008.

- Hefner J, Eisenberg D. Social support and mental health among college students. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2009;79(4):491–499. doi:10.1037/a0016918.

- Li Y, Peng J. Coping strategies as predictors of anxiety: Exploring positive experience of chinese university in health education in COVID-19 pandemic. CE. 2020;11(05):735–750. doi:10.4236/ce.2020.115053.

- Lechner WV, Laurene KR, Patel S, Anderson M, Grega C, Kenne DR. Changes in alcohol use as a function of psychological distress and social support following COVID-19 related University closings. Addict Behav. 2020;110(May):106527. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106527.

- Barzilay R, Moore TM, Greenberg DM, et al. Resilience, COVID-19-related stress, anxiety and depression during the pandemic in a large population enriched for healthcare providers. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10(1). doi:10.1038/s41398-020-00982-4.

- Governor of Ohio. Ohio Issues “Stay at Home” Order; New Restrictions Placed on Day Cares for Children. Available at https://governor.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/governor/media/news-and-media/ohio-issues-stay-at-home-order-and-new-restrictions-placed-on-day-cares-for-children. Published 2020.

- Governor of Ohio. Governor DeWine Announces Details of Ohio’s Responsible RestartOhio Plan. Available at https://governor.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/governor/media/news-and-media/covid19-update-april-27. Published 2020.

- Ohio Department of Health. COVID-19 Update: New Responsible RestartOhio Opening Dates. Available at https://coronavirus.ohio.gov/wps/portal/gov/covid-19/resources/news-releases-news-you-can-use/new-restartohio-opening-dates. Published 2020.

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, et al. New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2009;39:247–266.

- Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, et al. New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Soc Indic Res. 2010;97(2):143–156. doi:10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

- Zimet GD, Dahlem NW, Zimet SG, Farley GK. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1988;52(1):30–41. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2.

- Zimet GD, Powell SS, Farley GK, Werkman S, Berkoff KA. Psychometric Characteristics of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J Pers Assess. 1990;55(3-4):610–617. doi:10.1080/00223891.1990.9674095.

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. Int J Behav Med. 2008;15(3):194–200. doi:10.1080/10705500802222972.

- Kroenke K, SpitzerRobert L, Williams JBW, Löwe B. An ultra-brief screening scale for anxiety and depression: the PHQ-4. Psychosomatics. 2009;50(6):613–621.

- Huckins JF, da Silva AW, Wang W, et al. Mental health and behavior of college students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic: Longitudinal smartphone and ecological momentary assessment study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(6):e20185. doi:10.2196/20185.

- Son C, Hegde S, Smith A, Wang X, Sasangohar F. Effects of COVID-19 on college students’ mental health in the United States: Interview survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e21279– 14. doi:10.2196/21279.

- Wang X, Hegde S, Son C, Keller B, Smith A, Sasangohar F. Investigating mental health of US college students during the COVID-19 pandemic: Cross-sectional survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(9):e22817. doi:10.2196/22817.

- Salameh P, Salamé J, Waked M, Barbour B, Zeidan N, Baldi I. Risk perception, motives and behaviours in university students. Int J Adolesc Youth. 2014;19(3):279–292. doi:10.1080/02673843.2014.919599.

- Women and Anxiety. Anxiety & Depression Association of America. Availalble at https://adaa.org/find-help-for/women/anxiety. Published 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Women and Depression. Anxiety & Depression Association of America. Availalble at https://adaa.org/find-help-for/women/depression. Published 2021. Accessed August 13, 2021.

- Tosevski DL, Milovancevic MP, Gajic SD. Personality and psychopathology of university students. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2010;23(1):48–52. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e328333d625.

- Herrman H, Stewart DE, Diaz-Granados N, Berger EL, Jackson B, Yuen T. What is resilience? Can J Psychiatry. 2011;56(5):258–265. doi:10.1177/070674371105600504.

- Vázquez FL, Otero P, Díaz O. Psychological distress and related factors in female college students. J Am Coll Health. 2012;60(3):219–225. doi:10.1080/07448481.2011.587485.