Abstract

Objective

To assess whether and how beverage companies incentivize universities to maximize sugar-sweetened beverage (SSB) sales through pouring rights contracts.

Methods

Cross-sectional study of contracts between beverage companies and public U.S. universities with 20,000 or more students active in 2018 or 2019. We requested contracts from 143 universities. The primary measures were presence of financial incentives and penalties tied to sales volume.

Results

124 universities (87%) provided 131 unique contracts (64 Coca-Cola, 67 Pepsi). 125 contracts (95%) included at least one provision tying payments to sales volume. The most common incentive type was commissions, found in 104 contracts (79%). Nineteen contracts (15%) provided higher commissions or rebates for carbonated soft drinks compared to bottled water.

Conclusions

Most contracts between universities and beverage companies incentivized universities to market and sell bottled beverages, particularly SSBs. Given the health risks associated with consumption of SSBs, universities should consider their role in promoting them.

Introduction

People in the U.S. face myriad constraints on achieving healthy dietary patterns, including time,Citation1 access,Citation2 and affordability.Citation3,Citation4 Meanwhile, highly-palatable processed foods and beverages are readily accessible, often low-cost, and heavily marketed to consumers.Citation3,Citation5 Processed foods often contain added sugars, especially in the U.S., where packaged foods have a higher median sugar content than other countries, such as Australia.Citation6,Citation7 As a result of these factors, 62% of U.S. males and 66% of females ages 19 to 30 years exceed the recommended daily limit on calories from added sugars.Citation8

Sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs) are the top source of added sugars in the diet of the U.S. population.Citation8 Consuming SSBs is associated with increased risk for heart disease,Citation9,Citation10 diabetes,Citation11 dental disease,Citation12 and obesity.Citation13 For this reason, efforts to improve population health and reduce rates of chronic disease have focused on reducing consumption of SSBs.Citation14,Citation15

Coca-Cola and Pepsi – the two major sellers of SSBsCitation16 – are household names due, in part, to their massive advertising expenditures. Coca-Cola spent $280 million advertising its flagship beverage in the U.S. in 2019.Citation17 PepsiCo spent $224 million advertising its Pepsi brand that same year.Citation17

One way that Coca-Cola and Pepsi advertise their products is through incentive payments aimed at pushing retailers to sell more product through their distribution channels.Citation18,Citation19 Retailers such as convenience stores, grocery stores, and gas stations are known to receive such incentive payments for selling SSBs.Citation19 Coca-Cola and Pepsi also advertise their products through exclusive marketing agreements with venues and institutions, known as “pouring rights” contracts (PRCs). Previous studies examined PRCs at U.S. grade schools,Citation20–22 and found that these contracts included incentive payments. Johanson et al found that schools with PRCs received an average of $18 in annual per-student revenue from the contracts, $12 of which came from commissions on sales.Citation22 Briefel et al found that attending a middle school with a PRC was significantly associated with higher consumption of SSBs.Citation21 These studies raise concerns that incentive payments in PRCs may lead schools to maximize the sales of SSBs in order to maximize contract revenue.

While a 2016 rule from the U.S. Department of Agriculture established that U.S. grade schools are now prohibited from marketing SSBs,Citation23 there are no restrictions on marketing SSBs at public universities. Like PRCs at grade schools, university PRCs raise concerns because of their goal of promoting SSBs to a captive audience at an influential stage of development.Citation24 The gray literature suggests that many U.S. universities maintain PRCs.Citation25 However, no prior research has examined whether contracts between universities and beverage companies include incentive payments. Given that incentive payments in PRCs may affect the availability and marketing of SSBs on university campuses, and environments shaped by PRCs have been associated with increased consumption of SSBs, PRCs may affect SSB consumption and related adverse health outcomes among university students and other members of campus communities.

This paper aims to explore the prevalence of university PRCs, as well as to assess how and with what frequency these contracts incentivize public universities to maximize sales of SSBs on campus.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study of contracts between universities and beverage companies, we examined provisions within these contracts related to funding, marketing activities, health, and nutrition. The Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board (IRB) deemed this study to be exempt.

Data collection

We included all 143 four-year degree-granting public universities in the U.S. with 20,000 or more students, based on a search of the National Center for Education Statistics’ Integrated Postsecondary Education Data System in May 2019.Citation26 We submitted public records requests to each of these universities for contracts “offering rights to sell, market, promote, and/or advertise beverages” on campus. Initial requests were submitted in June and July 2019, and we conducted follow-up on missing or incomplete responses through September 2020.

To be included in our analysis, universities needed to have at least one contract with a beverage company that established the rights to sell beverages (at least two of the following: bottled water, soft drinks, sports drinks, juice, and energy drinks), and that was active at some point in between January 1, 2018 and December 31, 2019. We excluded universities that provided contracts with vending companies and sports management companies, but no contracts with Coca-Cola or Pepsi. We also excluded supplementary contracts with beverage companies other than Coca-Cola or Pepsi from universities that provided a primary contract (i.e., a contract with exclusivity provisions and/or sponsorship payments) with one of those two companies. If a university had multiple concurrent contracts with the same beverage company that met our inclusion criteria, we treated them as one contract. If a university had concurrent contracts with both Coca-Cola and Pepsi, we treated them as separate contracts. If a university provided multiple contracts that were active between 2018 and 2019, but one had ended and had been replaced by the other, we included only the more recent contract.

We identified data for abstraction based on our review of an initial sample of 10 contracts and themes from beverage contracts previously reported in the gray literature.Citation22,Citation25,Citation27 Two independent coders reviewed each contract in its entirety, capturing text from each contract on each type of provision, or indicating that no such provision was present. When contracts included minor redactions, coders captured as much information as possible or coded a provision as redacted. If entire sections of a contract were redacted, coders indicated that it was unclear whether certain provisions were present. Coders compared each review and reconciled differences through collaborative discussion until we reached consensus. Definitions of specific types of incentive, penalty, and marketing provisions included in this study (Commission, Rebate, Volume Incentive, Volume Minimum, Annual Contract Cash Revenue, Official Sponsor Designation, Official Beverage Designation, Use of University Marks, Sampling, Surveying, In-Kind Beverage Product, and In-Kind Equipment and Merchandise) can be found in . Examples of each provision type can be found in the Supplemental Materials.

Table 1. Definitions of specific types of financial incentive, penalty, and marketing provisions in contracts between Coca-Cola and pepsi and large public universities.

Data analysis

We used an inductive thematic analysis approach to categorize subtypes of provisions within each variable in our codebook and produced descriptive statistics using Microsoft Excel 2010 to characterize the prevalence of each provision type and subtype. We performed a chi-square test of independence to examine the relationships between beverage company and region of the United States,Citation28 presence of each type of incentive or penalty provision, and presence of select marketing provisions.

For commission provisions, in order to compare the incentives for selling carbonated soft drinks (CSD) compared with bottled water, we recorded the commission rate and vend price for 20 oz bottles of CSD and 20 oz bottles of water (Coca-Cola’s Dasani brand or Pepsi’s Aquafina brand). We calculated the average, range, and standard deviation of commission rates, vend prices, and commission revenue per bottle for each beverage type. We then counted the number of contracts with higher, lower, or equal commission rates, vend prices, and commission revenue per bottle between products. For rebate provisions, we calculated the mean, range, and standard deviation of rebates for 24-pack cases of 20 oz CSD and 20 oz water. We then counted the number of contracts with higher, lower, or equal rebates per case between products. For volume incentive provisions, we identified the volume trigger for each provision and calculated the average, range, and standard deviation of the minimum amount of units/year and percentage growth that triggered a volume incentive. We also calculated the average, range, and standard deviation of rebates per case for volume incentives structured as rebates.

For a subset of contracts that provided estimated annual revenue from commissions, rebates, or volume incentives, we calculated the mean, range, and standard deviation of revenue that could be earned from incentives and the proportion of average annual contract cash revenue estimated to derive from volume-based payments.

Results

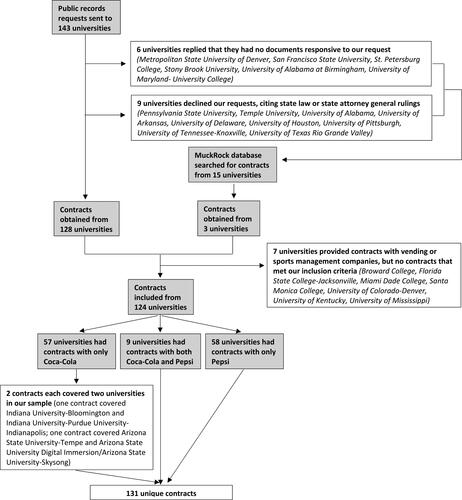

Of 143 universities to which we submitted public records requests, six responded stating that they had no documents responsive to our request; nine denied our request; and 128 produced at least one contract (). The nine universities that denied our request for contracts (listed in ) included three universities in Pennsylvania and one in Delaware that claimed the university and/or records were not subject to the state public records law; two universities in Texas that cited attorney general rulings stating that the universities may withhold the requested records to protect the proprietary interests of Coca-Cola; one university in Alabama and one in Tennessee that stated only state residents may make requests pursuant to their state public records laws; and one university from Arkansas that responded generally that the request did not meet the requirements of the state’s public records law. We searched the College Cola Contract Crowdsource database managed by MuckRock for contracts from the 15 universities that did not produce contracts and obtained contracts from three additional universities (totaling 131).Citation29

Of the 131 universities from which we obtained at least one contract, 124 universities from 38 states provided at least one contract that met our inclusion criteria (seven universities were excluded because they provided contracts with vending or sports management companies but provided no contracts that met our inclusion criteria). Of the 124 universities we included, 57 contracted with Coca-Cola only, 58 contracted with Pepsi only, and nine contracted with both. Twelve universities provided supplementary contracts with Dr. Pepper, Canada Dry, Gatorade, and/or Red Bull, but none had a primary contract with a beverage company other than Coca-Cola or Pepsi. Two contracts each covered two universities included in our sample. We analyzed a total of 131 contracts (64 Coca-Cola, 67 Pepsi). Both companies had contracts with universities across the United States, but Pepsi had a significantly greater presence than Coca-Cola in the West (p = 0.02), (differences between the presence of Coca-Cola versus Pepsi in the Midwest, Northeast, Southeast, or Southwest were not significant at p < 0.05). The length of the contracts’ initial terms ranged from one year to 25 years (mean = 8, SD = 4), with start dates ranging from 1997 to 2019. One-hundred and twenty-four contracts (95%) had at least one type of volume-based financial incentive or penalty and 73 contracts had multiple types. One-hundred and twenty-three contracts (94%) had at least one of provision granting specific marketing rights to the beverage company.

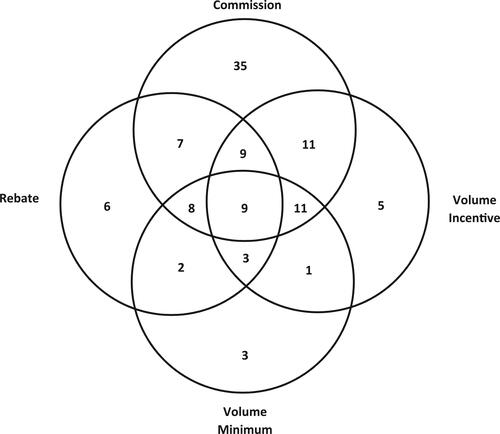

One-hundred and four contracts (79%) included commissions, 44 (34%) included rebates, 49 (37%) included volume incentives, 51 (39%) included volume minimums, and nine (7%) included all four ( & ). demonstrates the wide variability in combinations of incentives and penalties.

Figure 2. Prevalence of different combinations of incentives and penalties tied to sales volume in 131 contracts between beverage companies and large public universities in the United States.

Not pictured:

Commission & Volume Minimum: n = 14; Rebate & Volume Incentive: n = 0; No volume-based provisions: n = 6; Unclear whether contract contains volume-based provisions due to redaction: n = 1

*Numbers represent unique contracts.

Table 2. Prevalence of financial incentives and penalties tied to sales volume in contracts between Coca-Cola and Pepsi and large public universities.

Presence of commissions, rebates, and volume incentives was not associated with one beverage company or the other (p = 0.49, 0.10, and 0.15, respectively), but a higher proportion of Coca-Cola contracts than Pepsi contracts contained volume minimums (p = 0.03). Two contracts’ entire “Considerations” sections were redacted, making it unclear whether they included specific types of volume-based incentives. However, one of these contracts mentioned commissions in another section, making clear that it included at least one type of incentive.

Commissions

Commissions were present in more than half of the contracts with both Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Fifty-five contracts (42%) had Uniform commissions, meaning products were eligible for the same commission rate regardless of beverage type; 43 (33%) had Variable commissions, meaning commission rates were different for at least one type of beverage eligible for commissions; one (1%) applied a Uniform commission in some settings and a Variable commission in others; and five (4%) had commission rates redacted such that it was not possible to discern whether they were Uniform or Variable.

Ninety-six contracts specified the commission rate on 20 oz water and 20 oz CSD or offered commissions on CSD but not water (n = 2). The ranges (16-66%) were the same and mean (42% water, SD = 12%; 44% CSD, SD = 9%) commission rates were similar for both product types. Eighty-two contracts had identical commission rates for both, 11 provided a higher commission rate for CSD compared with water (or no commission on water), and three provided a lower commission rate for CSD compared with water.

Among 81 contracts for which we were able to assess commission revenue per bottle for CSD and water based on commission rates and vend prices, 62 contracts provided the same commission revenue for both products; 17 provided higher revenue for CSD or commissions on CSD but not water; and two provided higher revenue for water ().

Table 3. Cash value of annual revenue from commissions, rebates, and volume incentives in contracts between Coca-Cola and Pepsi and large public universities.

Rebates

Seventeen Coca-Cola and 27 Pepsi contracts included rebates. Thirty-nine (30%) of all 131 contracts included rebates on Cases of bottles and cans sold in retail or vending, and 13 (10%) included rebates on Gallons of flavored sirup used for fountain dispensing (including eight contracts with rebates for both Cases and Gallons).

Thirty-one contracts specified the rebate amount for cases of 20 oz water and 20 oz CSD, including one that provided higher rebates on CSD than water, one that provided rebates on CSD but not water, and two that provided rebates on water but not CSD.

Volume incentives

Thirty-five contracts (27%) offered volume incentives structured as rebates. Twenty of these were simple rebates (university earns the same cash or rebate value regardless of how much sales volume exceeds trigger threshold) and 15 were stepped rebates (provision includes increasing cash or rebate values triggered by increasing volumes of sales). Another 10 contracts offered volume incentives structured as cash payments, of which two were simple and eight were stepped. Five contracts offered volume incentives that were neither rebates nor cash payments, including two contracts with higher commission rates after the university achieved a volume target, two contracts with a commission on all revenue earned by the company above a specific revenue target, and one contract that provided an increase in university Sponsorship Fees proportional to the increase in annual company revenue.

The lowest level of growth that could trigger a volume incentive, among 14 contracts that specified a percentage growth above the previous year’s volume or some other baseline, ranged from 1%-10%.

Most volume incentive rebates did not specify product type, but one offered higher rebates for 20 oz sparkling and 16 oz energy beverages ($2.00/case) than on all other beverages ($1.00/case).

Cash value of incentives

Among 38 contracts with information on the minimum or guaranteed annual cash revenue from all incentives (commissions, rebates, and/or volume incentives), universities could earn up to $25,000-$775,000 (mean=$253,423, SD=$207,604) per year, accounting for 9-100% of the contract’s average annual cash revenue (mean = 29%, SD = 19%).

Volume minimum

Thirty-nine contracts (30%) had volume minimum adjustment provisions, six contracts (5%) had volume minimum termination provisions, five contracts (4%) had volume minimum extension provisions, and eight contracts (6%) had provisions that met our coding definition of volume minimum but did not fit these categories. These included three provisions stating that if the university fails to meet some unspecified volume threshold, Pepsi may remove Innovation Equipment (beverage dispensing equipment considered by Pepsi to be innovative or updated technology); two stating that the company could alter pricing or add delivery fees if minimums were not met; two stating that the university will not receive any commission payments if commissions fail to reach a specified amount; one stating that if the university decided to “limit the portfolio of products and package sizes offered … Pepsi Beverages Company reserves the right to propose an adjustment to the financial proposal offered”; and one that specified a minimum volume commitment in cases and gallons, but did not specify any particular outcome should the university fail to meet the commitment.

Adjustments tied to a percentage decrease in volume below the previous year’s volume or some other baseline (n= 33) were triggered by a decrease of between 5%-30%. For 31 contracts with adjustment provisions (29 Coca-Cola, 2 Pepsi), the financial penalties faced by the universities were characterized only in general terms (e.g., “Sponsor [beverage company] may elect to adjust the Sponsorship Fees and other consideration to be paid to the University to fairly reflect the diminution of the value of the rights granted to Sponsor”). The other eight contracts (all Pepsi) included dollar values or formulas to calculate the decrease in payments to the universities.

Terminations tied to a percent decrease in volume or revenue (n = 4) were triggered by a decrease of between 20%-50%. One contract stated that the company could terminate the agreement if the university failed to meet an unspecified volume required for the placement of “Innovation Equipment.” The remaining contract stated that if the university fails to meet a “Volume Threshold” of 1.4 million cases and gallons by the end of the 25-year contract term, the company may “terminate the Agreement and obtain a recovery pursuant to the terms and conditions outlined herein.”

Marketing rights

Most contracts outlined a series of marketing rights that the beverage company would be granted in exchange for payments to the university. For example, 96 contracts (73%) explicitly granted the company rights to advertise itself as a sponsor of the university or at least one of its components (e.g., the athletics department) (). Similarly, 96 contracts (73%) granted the company rights to advertise its products as official or exclusive beverages of the university. One-hundred and thirteen contracts (86%) granted the company permission to use the university’s marks (e.g., name, logos, colors, and mascots) in promotional activities. Ninety-three contracts (71%) specified that the company could conduct sampling events on campus, and 53 contracts (40%) specified that the company could conduct surveys (i.e., marketing research) on campus. Companies also committed to providing free cases of beverage product in 109 contracts (83%) and free equipment or merchandise in 73 contracts (56%) to increase brand exposure on campus. Each of these types of marketing provisions were found in contracts with both Coca-Cola and Pepsi. Provisions regarding surveys were more common in Coca-Cola contracts than Pepsi contracts (p < 0.01) and provisions regarding free equipment or merchandise were more common in Pepsi contracts than Coca-Cola contracts (p = 0.02) (all other types of marketing provisions were equally likely to be found in contracts with Coca-Cola and Pepsi).

Table 4. Prevalence of select marketing provisions in contracts between Coca-Cola and pepsi and large public universities.

Among eight contracts that did not include any of these marketing provisions, five contracts (4 Coca-Cola, 1 Pepsi) were with universities that had both Coca-Cola and Pepsi contracts (and only one contract included marketing rights), one contract (Pepsi) included other marketing rights related to athletics such as signage and announcements at athletic events, one contract (Pepsi) mentioned that “the University granted exclusive licenses for the use of its marks through [an] Athletics agreement” but this agreement was not included with the response to our FOIA request, and one contract (Coca-Cola) was a beverage service agreement without marketing rights but the university’s website described an exclusive pouring rights contract with Pepsi that was not included with the response to our FOIA request.Citation30

Discussion

In this study of contracts between beverage companies and large public universities, most universities (87%) provided a contract with Coca-Cola, Pepsi, or both, and nearly all of these contracts (95%) had at least one type of incentive or penalty tied to sales volume. Incentives were equally common in Coca-Cola and Pepsi contracts, but Coca-Cola contracts were more likely to contain penalties. We found that universities can earn hundreds of thousands of dollars (some even millions) per year from volume-based payments, providing substantial incentives to maximize product sales. Several universities received greater incentives to sell SSBs than bottled water, potentially incentivizing the promotion of SSBs or disincentivizing university-led efforts to reduce SSB consumption on campus. Most contracts (94%) granted marketing rights to beverage companies, allowing them to advertise beverages on campus and in association with the university.

No prior research has examined contracts of this type, but two studies have evaluated universities’ efforts to reduce sales and promotion of SSBs on campus. In 2015, University of California-San Francisco eliminated SSBs from all campus and medical center venues.Citation31 A study of 214 university employees found a significant 49% decrease in average SSB intake up to one year following the sales ban.Citation31 In 2018, University of British Columbia modified its contract with Coca-Cola to eliminate promotion of SSBs and began implementing an initiative to support healthier beverage choices.Citation32 University of British Columbia piloted removal of SSBs in one dining hall and found no difference in loss of revenue compared with similar campus dining locations.Citation32

Additionally, a study that looked at awareness and opinions of PRCs among 915 students, faculty, and staff at one large, public Midwestern university found that 64% were not previously aware of PRCs, 31% disagreed with universities engaging in pouring rights contracts, and “health concerns” related to SSB consumption was the most common argument against PRCs.Citation33

Despite these examples, our findings demonstrate that most universities continue to promote and sell SSBs through PRCs. Many universities identify as “anchor institutions” with roles in promoting social good, including making positive contributions to neighborhood health.Citation34 Given the health harms associated with SSBs,Citation9–13 universities have an opportunity to change habits and norms surrounding these products by reforming or opting out of PRCs. However, universities may confront barriers to amending or exiting these contracts. Universities that pursue PRCs with an increased focus on health and nutrition may find that the contracts still conflict with those universities’ commitments toward environmental sustainability. For example, the University of California system has committed to phase out procurement of beverages in single-use plastic bottles.Citation35 However, our study found that University of California campuses maintain PRCs which include agreements to sell bottled beverages. Since plastic bottles are made from fossil fuels and require substantial greenhouse gas inputs to manufacture,Citation36 obligations to market and sell bottled beverages under PRCs may also run counter to universities’ commitments to work toward carbon neutrality.Citation37

Universities opting out of PRCs will have to ensure alternative hydration, such as filtered tap water stations, are readily accessible. Universities will also need to consider the impact of cutting ties with beverage companies on the programs and services that these companies fund. Corporate partnerships such as those with Coca-Cola and Pepsi may provide revenue to universities struggling with loss of revenue from other sources. College enrollment has been declining for years,Citation38 and the COVID-19 pandemic has presented additional financial hardships to universities due to tuition discounting, declining international student enrollment, suspension of athletic programs, and declining support from state governments.Citation39 As one scholar noted in reference to universities and tobacco money, “[T]here are few, if any, corporate sources of untainted funds… As the pressure on universities to find private sources of funding intensifies, academia will be faced with difficult decisions about where to draw the line.”Citation40

Previous research has drawn parallels between the marketing practices of the tobacco industry and the food and beverage industry.Citation41–44 Amidst growing concern over the health effects of cigarettes and unhealthy foods, both industries employed tactics to maintain sales and boost public perception including disputing science in order to instill doubt about the links between products and health harms, launching corporate social responsibility campaigns, and attempting to influence government policy.Citation43,Citation44 Studies have also found that tobacco companies provide financial incentives to retailers,Citation45 similar to those described in this study provided by beverage companies to universities. In 2015, Quebec, Canada passed legislation that explicitly prohibits this practice of tobacco companies offering rebates, gratuities, or other benefits to retailers.Citation46 Similar policies restricting tobacco advertising and promotional activities have been associated with reduced tobacco consumption,Citation47 suggesting they may be useful for reducing consumption of SSBs.

In the United States, the federal government, states, and localities are beginning to pass policies to restrict marketing and advertising of SSBs. In 2016, the U.S. Department of Agriculture issued regulations prohibiting the marketing of food and beverages that fail to meet federal nutrition standards (including SSBs) in elementary, middle, and high schools.Citation23 More than two dozen jurisdictions have passed policies that prohibit SSBs from being the default beverage option for kids’ meals at chain restaurants.Citation48 And in 2020, Berkeley, California passed an ordinance removing SSBs and other unhealthy foods from grocery checkout aisles.Citation49

Several states and localities have also adopted policies that set nutrition guidelines for foods and beverages served and sold in public settings.Citation50 Some of these policies address the sale of SSBs at public universities, but implementation and enforcement in those settings has not been examined. In February 2021, the New York state legislature introduced a bill that would explicitly bar public institutions from promoting SSBs and prohibit public agencies from entering into contracts with volume minimums for SSBs.Citation51 If such a bill passed, it could have important implications for PRCs and SSB reduction efforts.

Strengths of this study include the inclusion of all large public universities and double coding of contracts by different reviewers. The study also had limitations. Our sample included just 18% of public four-year universities and 5% of all four-year universities because we did not include contracts with smaller or private U.S. universities, and therefore generalizability is limited.Citation26 Also, our analysis of the cash value of contracts may not represent our entire sample. We described the provisions present in these contracts, and not the ways in which those provisions are operationalized to inform marketing and sales practices on campuses. Therefore, we were not able to describe any of the actual on-campus advertising practices; where beverages were available on campus; or the extent to which universities received the incentives outlined in their contracts. We did not differentiate between contracts by settings, such as dining halls, campus retail outlets, athletics venues, and hospitals. Finally, we were unable to obtain contracts from some universities which could have biased our sample. In addition to universities that declined to provide contracts citing state laws or attorneys general’s rulings, some universities that responded as having no documents responsive to our request appear to have financial relationships with beverage companies.Citation52,Citation53

Future research should explore additional marketing strategies used in PRCs and variation in contracts based on characteristics such as school size; transparency issues surrounding public disclosure of the terms of university-corporate partnerships; strategies to reduce SSB consumption on university campuses by either modifying or removing contracts with beverage companies; and the impact of modifying or removing such contracts on the health of students, faculty, and staff and the finances of the universities.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements of the United States and was deemed exempt by the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Institutional Review Board.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Rahkovsky IJ, Carlson A. Consumers balance time and money in purchasing convenience foods. 2018. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/89344/err-251.pdf?v=0

- Ver Ploeg M, Larimore E, Wilde P. The influence of foodstore access on grocery shopping and food spending. 2017. https://www.ers.usda.gov/webdocs/publications/85442/eib-180.pdf

- Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Contribution of food prices and diet cost to socioeconomic disparities in diet quality and health: a systematic review and analysis. Nutr Rev. 2015;73(10):643–660. doi:10.1093/nutrit/nuv027

- Conrad Z, Reinhardt S, Boehm R, McDowell A. Higher-diet quality is associated with higher diet costs when eating at home and away from home: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2005–2016. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(15):5047–5057. doi:10.1017/S1368980021002810.

- Fazzino TL, Rohde K, Sullivan DK. Hyper-palatable foods: development of a quantitative definition and application to the US food system database. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2019;27(11):1761–1768. doi:10.1002/oby.22639

- Baldridge AS, Huffman MD, Taylor F, et al. The healthfulness of the US packaged food and beverage supply: a cross-sectional study. Nutrients 2019;11(8):1704. doi:10.3390/nu11081704.

- Crino M, Sacks G, Dunford E, et al. Measuring the healthiness of the packaged food supply in Australia. Nutrients 2018;10(6):702. doi:10.3390/nu10060702.

- Dietary Guidelines for Americans, 2020–2025 (2020).

- Malik VS, Hu FB. Fructose and cardiometabolic health: what the evidence from sugar-sweetened beverages tells us. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;66(14):1615–1624. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2015.08.025

- Fung TT, Malik V, Rexrode KM, Manson JE, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sweetened beverage consumption and risk of coronary heart disease in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(4):1037–1042. doi:10.3945/ajcn.2008.27140.

- Malik VS, Popkin BM, Bray GA, Després J-P, Willett WC, Hu FB. Sugar-sweetened beverages and risk of metabolic syndrome and type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(11):2477–2483. doi:10.2337/dc10-1079.

- Laniado N, Sanders AE, Godfrey EM, Salazar CR, Badner VM. Sugar-sweetened beverage consumption and caries experience: An examination of children and adults in the United States, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2011–2014. J Am Dent Assoc. 2020;151(10):782–789. doi:10.1016/j.adaj.2020.06.018.

- Bremer AA, Auinger P, Byrd RS. Sugar-sweetened beverage intake trends in US adolescents and their association with insulin resistance-related parameters. J Nutr Metab. 2010;2010:1–8. doi:10.1155/2010/196476.

- von Philipsborn P, Stratil JM, Burns J, et al. Environmental interventions to reduce the consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and their effects on health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;6(6):CD012292. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD012292.pub2

- Krieger J, Bleich SN, Scarmo S, Ng SW. Sugar-sweetened beverage reduction policies: progress and promise. Annu Rev Public Health. 2021;42:439–461. doi:10.1146/annurev-publhealth-090419-103005

- Conway J. Market share of leading CSD companies in the U.S. 2004–2019. Statista Research Department. https://www.statista.com/statistics/225464/market-share-of-leading-soft-drink-companies-in-the-us-since-2004/

- Ad spend of selected beverage brands in the U.S. 2019. Statista Research Department. https://www.statista.com/statistics/264985/ad-spend-of-selected-beverage-brands-in-the-us/

- Feighery EC, Ribisl KM, Achabal DD, Tyebjee T. Retail trade incentives: how tobacco industry practices compare with those of other industries. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(10):1564–1566. doi:10.2105/ajph.89.10.1564.

- Laska MN, Sindberg LS, Ayala GX, et al. Agreements between small food store retailers and their suppliers: incentivizing unhealthy foods and beverages in four urban settings. Food Policy. 2018;79:324–330. doi:10.1016/j.foodpol.2018.03.001.

- Nestle M. Soft drink "pouring rights": marketing empty calories to children. Public Health Rep. 2000;115(4):308–319. doi:10.1093/phr/115.4.308

- Briefel RR, Crepinsek MK, Cabili C, Wilson A, Gleason PM. School food environments and practices affect dietary behaviors of US public school children. J Am Diet Assoc. 2009;109(2):S91–S107. doi:10.1016/j.jada.2008.10.059.

- Johanson J, Smith J, Wootan M. Raw deal: school beverage contracts less lucrative than they seem. 2006. https://cspinet.org/sites/default/files/attachment/beveragecontracts.pdf

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. National School Lunch Program and School Breakfast Program: nutrition standards for all foods sold in school as required by the Healthy, Hunger-Free Kids Act of 2010. 81 Federal Register 501322016; 2016.

- Nelson MC, Story M, Larson NI, Neumark-Sztainer D, Lytle LA. Emerging adulthood and college-aged youth: an overlooked age for weight-related behavior change. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(10):2205–2211. doi:10.1038/oby.2008.365

- Komatsoulis C. The biggest college rivalry in America: Coke versus Pepsi. MuckRock. https://www.muckrock.com/news/archives/2018/aug/27/colleges-coke-vs-pepsi/

- National Center for Education Statistics. Integrated postsecondary education data system. https://nces.ed.gov/ipeds. Accessed May 2019.

- Cecil AM. Pouring rights: academic misconduct. Crossfit Journal. 2017. https://journal.crossfit.com/article/pouring-rights-cecil-2

- Geographic N. United States Regions. https://www.nationalgeographic.org/maps/united-states-regions/

- MuckRock. College Cola Contract Crowdsource. https://www.muckrock.com/foi/list/?page=1&per_page=100&date_range_0=07%2F20%2F2018&status=done&q=Pepsi

- University of Wisconsin Milwaukee. Student organizations manual.

- Epel ES, Hartman A, Jacobs LM, et al. Association of a workplace sales ban on sugar-sweetened beverages with employee consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages and health. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(1):9–8. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4434.

- Di Sebastiano KM, Kozicky S, Baker M, Dolf M, Faulkner G. The University of British Columbia healthy beverage initiative: changing the beverage landscape on a large post-secondary campus. Public Health Nutr. 2021;24(1):125–135. doi:10.1017/S1368980020003316

- Thompson HG, Whitaker KM, Young R, Carr LJ. University stakeholders largely unaware and unsupportive of university pouring rights contracts with companies supplying sugar-sweetened beverages. J Am Coll Health. 2021:1–8. doi:10.1080/07448481.2021.1891920.

- Ehlenz MM. Defining university anchor institution strategies: comparing theory to practice. Plan Theory Pract. 2018;19(1):74–92. doi:10.1080/14649357.2017.1406980.

- University of California Office of the President. Policy on sustainable practices. 2020.

- Benavides PT, Dunn JB, Han J, Biddy M, Markham J. Exploring comparative energy and environmental benefits of virgin, recycled, and bio-derived pet bottles. ACS Sustainable Chem Eng. 2018;6(8):9725–9733. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b00750.

- Earls M. Colleges commit to carbon neutrality. Getting there is hard. Second Nature. https://secondnature.org/media/colleges-commit-to-carbon-neutrality-getting-there-is-hard/

- National Student Clearinghouse Research Center. Overview: spring 2021 enrollment estimates. 2021. https://nscresearchcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/CTEE_Report_Spring_2021.pdf

- Friga PN. How much has Covid cost colleges? $183 Billion. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-fight-covids-financial-crush

- Cohen JE. Universities and tobacco money. BMJ. 2001;323(7303):1–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7303.1.

- Nguyen KH, Glantz SA, Palmer CN, Schmidt LA. Tobacco industry involvement in children’s sugary drinks market. BMJ. 2019;364:l736. doi:10.1136/bmj.l736

- Nguyen KH, Glantz SA, Palmer CN, Schmidt LA. Transferring racial/ethnic marketing strategies from tobacco to food corporations: Philip Morris and Kraft General Foods. Am J Public Health. 2020;110(3):329–336. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2019.305482

- Dorfman L, Cheyne A, Friedman LC, Wadud A, Gottlieb M. Soda and tobacco industry corporate social responsibility campaigns: how do they compare? PLoS Med. 2012;9(6):e1001241. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1001241

- Brownell KD, Warner KE. The perils of ignoring history: big tobacco played dirty and millions died. How similar is big food? Milbank Q. 2009;87(1):259–294. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2009.00555.x

- Reimold AE, Lee JGL, Ribisl KM. Tobacco company agreements with tobacco retailers for price discounts and prime placement of products and advertising: a scoping review. Tob Control. 2022:1–10. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2021-057026.

- Government of Quebec. Tobacco control act. 2015.

- Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21(2):147–153. doi:10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416

- Center for Science in the Public Interest. State and local restaurant kids’ meal policies. 2021. https://cspinet.org/sites/default/files/attachment/CSPI_chart_local_kids_meal_policies_November_2021.pdf

- Berkeley City Council. Ordinance No. 7, 734-N.S. 2020.

- Silverman J, Amico A. A roadmap for comprehensive food service guidelines. 2019. https://cspinet.org/sites/default/files/attachment/Roadmap_for_Comprehensive_FSG_5-6-21.pdf

- New York State Assembly. Assembly Bill A5682A. 2021–2022.

- Board of Directors Minutes-November 16, 2018. Stony Brook University. https://www.stonybrook.edu/commcms/fsa/about/board-of-directors/_2018-11-16.php. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- University of Alabama and Coca-Cola Seal Refreshing Deal on Campus. PRNewswire. https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/university-of-alabama-and-coca-cola-seal-refreshing-deal-on-campus-300677527.html