Abstract

Objective: This study determined the frequency, reasons for, and side effects of energy drinks (ED) consumption among online students. Participants: Students attending an online university. Methods: Participants were recruited by email and completed a 59-question survey about their prior months ED practices using a combination of validated surveys previously published examining similar constructs in on-campus students. Results: 307 students (age = 32.4 ± 6.5yrs) completed the survey, and 88% reported consuming EDs. Students’ reasons for consuming ED included school (p < .001), work (p < .001), an event/competition (p < .001), pick me up (p < .001), lack of rest (p < .001), more energy (p < .001), and staying awake while driving (p < .001). Only individuals who consumed >10 ED/month reported side effects of headaches (p = .01) and speeding (p = .01). Conclusions: In our sample, a majority of the participants reported consuming ED for various daily activities. Only frequent consumers reported side effects suggesting they had become habituated to caffeine since they drank EDs despite experiencing side effects.

Introduction

The energy drink (ED) market has grown exponentially over the past two decadesCitation1 and is anticipated to grow at 8.2% over the 2020–2027 period.Citation2 The surge, in part, resulted from successful marketing to a target population of young adults between the ages of 18–24 years,Citation3 the younger Millennials and now Gen Z, many of whom are college students. Millennials grew up during the expansion of the Internet, while technology was a central part of Gen Zer’s upbringing.Citation4 Therefore, the marketing strategy is predominantly rooted in an online platform,Citation5 and the online community is densely populated with these young adults.Citation6

Another key factor in the continued growth rate is the variety of energy drink options.Citation7 The definition of an energy drink is a nonalcoholic beverage or dietary supplement that contains caffeine and other additives that provide stimulant energyCitation8,Citation9 such as taurine, guarana, B vitamins, sugarsCitation9, yerba mate, ginsengCitation10, L-carnitine, glucuronolactone, cocoa nut, kola nutCitation11, and milk thistle.Citation12 There is limited scientific evidence to support their energy stimulant claims; however, there is evidence that some of these added ingredients may modulate the effects of caffeine.Citation13 In addition, many energy drink companies have developed proprietary blends of ingredients. These combinations of ingredients in varying quantities determine the flavor as well as the amount and duration of the drink’s "energy boost."Citation14 Because of the instant boost in energy, alertness, and physical and mental stimulation provided by energy drinks, consumer growth, and marketing are now reaching older generations.Citation15

As the growth rate in ED consumption increases, there is the potential for users to become dependent on ED to meet daily obligations, which can lead to a caffeine use disorder or addiction. A study of New Zealanders suggested one in five people may have a caffeine use disorder.Citation16 Thus, ED addiction is a health concern but identifying caffeine addiction in an individual is more difficult to define than other addictive substances, such as drugs or alcohol, because ED is a socially acceptable substance. As a result, many caffeine addicts are self-diagnosed, and there is debate as to whether or not caffeine is a potent enough substance to cause addiction.Citation17

Online college was previously associated with adults over 25 years of age or returning students who have jobs, families, and other obligations making online classes the best option to obtain a college education. But, the enrollment of online college students under 25 is increasing as young adults opt for online enrollment because of lower cost, more scheduling flexibility, and a greater familiarity with navigating online courses.Citation18 Also, the COVID-19 pandemic shifted in-person learning at brick-and-mortar universities to online classes making that, in some cases, the only safe option for a college education.Citation19 Studies have shown that more than 51% of students at in-person learning universities consumed more than one ED each month during the semester and one reason those students reported using ED was for schoolwork.Citation20 The shift of in-person learning to online will likely increase the population of online college students using ED, making it critical to understand the factors that drive online college students to consume ED.

Most of the peer-reviewed research studies have focused on the use of ED by students who attend classes in-person at brick-and-mortar colleges and universities. To our knowledge, there are no studies that have examined the ED intake of students who attend an online university. Studies of students attending institutions with in-person learning find ED are used for various reasons.Citation10,Citation20–24 These reasons include compensating for lack of sleep, remaining alert to study for an exam or to work on a projectCitation20, improving athletic performanceCitation21,Citation22, and mixing with liquor.Citation10,Citation20,Citation23,Citation24 It is not known if online students also consume ED for the same reasons. The purpose of this study was to determine if online college students consume ED, why they consume ED, and if they experience any side effects.

Materials and methods

Study design

An online survey was used to collect cross-sectional data on the ED use of students attending a dedicated online higher education institution. The hypotheses that online college students consume energy drinks and how much they consumed in the month before taking the survey were the primary endpoints. The secondary endpoints determine why online college students consume energy drinks and the side effects experienced. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at the American Public University System (APUS).

Recruitment

Subjects were recruited from the Sports and Health Sciences (SHS) and Sports Management (SM) programs at APUS. All classes are virtual, so the student does not attend a physical location. Instead, faculty and students can be located anywhere there is Internet access. The University is accredited and grants associate, bachelor, master, and doctoral degrees. It is a public university open to any student and enrollment in 2020 was 50,000.Citation25 The University has a small, physical location in Charles Town, WV, where specific functions that require a physical location, such as computer support, are completed. The APUS student population is older (median age 32 years), and 88% are working adults. Students live in all 50 states and more than 100 countries, and most are transfer students from other universities. Approximately 60% are on active duty in the military.Citation26

An email invitation to participate in the study was sent to each student in the SHS and SM programs. The email included a description of the study, invited the student to take the survey, and provided a link to the survey. The survey was administered through Survey Monkey. The email invitation was sent to 5,581 students by the SHS and SM administrator. The number of emails returned as "undelivered," and the number of unopened emails was not available. A response rate of <6% is estimated based on the number of emails sent.

Survey

Survey questions (see supplement) were derived from two previously published studies (one published by Malinauskas et alCitation20 and one by Marczinski et alCitation27) that collected information on ED consumption of college students who attended in-person classes at brick-and-mortar institutions. In addition, the International Physical Activity Questionnaire (IPAQ)Citation28 was included to assess physical activity.

The survey was administered online using Survey Monkey Inc. (Survey Monkey, Inc, San Mateo, CA) and consisted of 59 questions that took approximately 20 minutes to complete. The first question required the potential participant to read the consent form and either accept or decline to participate in the study. If they agreed to participate in the study, they were given access to the survey.

Three questions collected demographic information (age, gender, race, and marital status). Three questions asked about their degree and length of association with the university. Four questions asked about employment and how many hours they spent per week on school-related work. Six questions asked about ED consumption and whether they consumed ED for schoolwork, work, event, or competition, a "pick me up," lack of rest, more energy, and staying awake while driving. Respondents were also asked whether they experienced any adverse side effects, specifically headaches, jitters, "jolt and crash," heart palpitations, "speeding," and shaking.

Ten questions asked how many times and how much they drank for several situations such as insufficient sleep, when they needed more energy, when they had to study for an exam or major project, when they drove for an extended period, as an alcohol mixer, or to recover from a hangover. If they responded, "yes," they were asked the number of ED they consumed per day for that situation.

Three questions asked the respondent if they had a positive or negative experience consuming ED, if they enjoyed drinking ED, and how much they spent on ED. One question asked about their knowledge and awareness of various ED ingredients such as taurine, guarana, B-vitamins. This question also asked about their beliefs on the safety and effectiveness of energy drinks compared to other caffeinated beverages and pills. Lastly, they were asked to rate their caffeine consumption.

The remaining questions asked about their physical activity using the long version of the IPAQ converted to an online format. The IPAQ was included to assess the relationship between physical activity and ED intake.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using SPSS software (IBM Corp. Released 2020. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp) and Excel (Office 365 ProPlus version). All continuous data were tested for normality of distribution using a combination of histograms and the Shapiro-Wilks test for normality. None of the continuous variables measured in our primary outcome (quantity of energy beverages consumed for various activities) were normally distributed (p < .05). We used a combination of logarithmic, arscine, exponential, and power transformation techniques; however, we were unable to transform both groups to be normally distributed. Since all groups had >30 participants, we justify using parametric analyses using large sample theory.Citation29,Citation30 To identify demographic characteristic differences between groups, we used a combination of Chi-square tests and t-tests to test for differences between groups. After identifying significant differences, we used a series of logistic regressions to identify differences in side effects, reasons for consuming energy beverages, and knowledge of energy beverages. To correct for multiple analyses, we used a Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple analysesCitation31 using a FDR value of 0.10 for each set of hypotheses. Post-hoc, G*Power (v. 3.1) was used to calculate power for all models. When examining the quantity of energy beverages consumed, we used an Analysis of CoVariance (ANCOVA) to determine group differences between beverages. For these analyses, we report Effect Size (ωCitation2) and post-hoc power for all of our analyses. We used a Benjamini-Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction for multiple analyses using a FDR value of 0.10 or 10%.

Results

Subjects

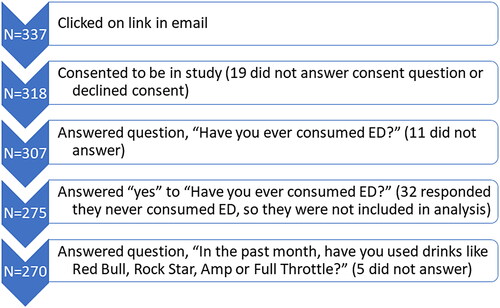

provides details on final subject inclusion. Three hundred and seven subjects were included in the study. Thirty-two did not consume an ED, and 5 said they did not drink an ED in the month prior to the study, so these subjects were not included in the analysis examining factors related to the frequency of ED consumption.

Two hundred and seventy subjects drank ED (). ED drinking frequency was further divided into subjects who infrequently (INFREQ) and frequently (FREQ) drank ED based on the number of ED they consumed in the month prior to the study. INFREQ was defined as a participant who consumed no energy drinks during the month before taking the survey. In contrast, FREQ consumed at least one energy drink within the month before taking the survey. The FREQ drinkers were further subdivided based on the number of ED consumed in the last month. If they consumed <10 ED in that month, they were labeled FREQ < 10, while those who consumed >10 ED were labeled FREQ > 10.

Thirty-two subjects, or 11.6%, responded they never consumed an energy drink. Of the subjects who had tried an ED, 57% had consumed at least one in the month prior to the study, while 43% had not.

The average age for all subjects was 32.4 ± 6.5 years and ranged from 20 to 55 years. The median age was 30 years. Sixty-nine percent (n = 185) were male and 31% (n = 85) were female. The subjects had attended APUS for 2 ± 2.4 years (median = 2). Eighty percent were in a relationship, married, or engaged, while 20% were divorced, single, or widowed. Ninety-one percent were employed, and 71% worked for the military. Of these, 63% said they worked more than 40 h per week. Forty-six percent of those participants that worked more than 40 h a week spent 6–10 h per week studying, while 24% spent 11–15 h per week.

Between the FREQ and INFREQ drinkers, there were no significant differences in age or physical activity level (). The distribution of marital status, employment status, or the number of hours spent studying was similar between FREQ and INFREQ ED consumers and FREQ < 10 and FREQ > 10. Males were more likely than females to consume energy drinks and to consume larger amounts of ED. INFREQ drinkers were less likely to be employed by the military and worked less than 40 h. The military employed 85% of the subjects who drank more than 10 ED per month.

Table 1. Subject characteristics.

ED side effects include headaches, jitters, jolt, heart palpation, speeding, and shaking (). Neither the INFREQ nor FREQ drinkers reported experiencing these side effects. The only group that reported experiencing side effects was the FREQ > 10, and they were more likely to experience headaches and speeding. Additionally, FREQ > 10 reported significantly more adverse effects of consuming energy beverages than FREQ < 10 (1.80 ± 0.21 (FREQ > 10) vs. 1.25 ± 0.17 (FREQ < 10)), p = 0.046).

Table 2. Frequency subjects experienced specific adverse side effects associated with consuming energy drinks.

FREQ users consumed ED for school, work, competition or event, pick me up, lack of rest, more energy, and keep awake while driving (). In contrast, among the FREQ drinkers, FREQ > 10 was more likely to consume ED for school, work, competitive events, and more energy than the FREQ < 10. Neither group consumed ED for lack of rest, to keep awake, or as a pick me up.

Table 3. The number of subjects that used energy drinks for specific daily activities.

INFREQ and FREQ drinkers differed significantly in quantity and how often they drank because they lacked sleep, they were studying for an exam or major project, and driving (). The same pattern of these life activities was seen between the FREQ > 10 and FREQ < 10. At parties, FREQ drinkers were more apt to mix alcohol with their ED, but they did not attend more parties than INFREQ; they just reported mixing more ED with alcohol than the INFREQ. Among FREQ < 10 vs. FREQ > 10 drinkers, there was no difference in the number of ED mixed with alcohol and how often they attended parties. Both groups had the same ED usage pattern for a hangover.

Table 4. Quantity of energy drinks consumed for specific daily activities.

The data suggested mixed results regarding beliefs about energy drinks, the user’s awareness of some common ingredients, the safety and effectiveness of energy drinks, and other caffeine-based drinks and substances and beliefs about their caffeine intake (). There was no difference between INFREQ and FREQ users in their awareness of taurine, guarana, and B-vitamins or other enhancing ingredients; however, there was a greater awareness of the enhancing ingredients in ED by the FREQ < 10, particularly B-vitamins compared to the FREQ > 10 groups. Additionally, FREQ users believed energy drinks were safer than energy pills and more effective than coffee and soft drinks than INFREQ users. Of the frequent user group, FREQ < 10 users believed energy drinks were more effective than coffee and soft drinks than the FREQ > 10 group (). Also, the FREQ < 10 thought they consumed too much caffeine.

Table 5. Respondents’ agreement/disagreement with the following statements.

The number of ED consumed was significantly correlated with total vigorous physical activity (p = 0.015, R2=0.385). However, ED consumption was not correlated with total physical activity, total moderate activity, total walking, moderate-vigorous physical activity, and time spent sitting during the week and weekend.

Discussion

The distinction between brick and mortar and online colleges/universities has become blurred over the last decade as many brick and mortar institutions offer in-person learning and 100% online classes. This survey was conducted at a university that is entirely virtual or online, allowing students to earn college credit and/or a degree anywhere there is Internet connectivity. Earlier studies reported the use of ED by students who attended in-person classes at brick-and-mortar universities. Our study found online students consumed ED with similar drinking patterns (frequency, side effects, and reasons for consumption) as studies published about students who attend higher educational institutions with in-person learning.

Malinauskas et alCitation20 were the first to report ED use among brick-and-mortar students, and they reported 51% of their participants consumed more than one ED each month for the current semester. Using their survey, our study found 90% of the subjects consumed at least one ED the month prior to the study, nearly double. Several reasons might explain the considerable difference, such as sampling bias or the makeup of the student bodies (e.g., age, marital status, and employment). Our students were recruited from two select curricula, and potential subjects were told the study was about ED consumption, which may have artificially inflated the percent of reported ED drinkers.

Differences in age, marital status, and employment may have contributed to the greater number of ED consumers we observed in our study. In 2017, The National Center for Education Statistics (NCES)Citation32 published enrollment patterns and demographic characteristics of undergraduates who attend "for-profit" and "nonprofit" or "public" institutions. Our online university is considered a for-profit institution according to NCES criteria, while Malinauskas et alCitation20 survey was conducted at a nonprofit/public institution located in the Central Atlantic region of the United States. NCES reported a mean age of 30, 26.1, and 24.7 at for-profit, public, and private nonprofit, respectively. The percentage of age 23 or younger students attending for-profit, public, and private nonprofit was 31.6%, 57.7%, and 70.3%, respectively. This data suggests that older students attend for-profit universities and, indeed, our subjects reflect this age demographic. Several studiesCitation33,Citation34 have shown that caffeine, the primary stimulant in ED, usage increases with age. There is approximately ten years difference in age between our study and those of nonprofit institutions like Malinauskas et al.Citation20

Two-thirds of our subjects were married, and two-thirds of those consumed ED compared to 12-16% of those who reported they were single. Park et alCitation35 found married people compared to nonmarried, 61% vs. 39%, respectively, were more likely to drink ED, but Berger and colleaguesCitation36 found that older married adults were less likely to drink ED.

Caffeine consumption has been positively associated with the number of hours worked.Citation34 Most of our survey participants were employed, and more than 60% were by the military. More than half reported working more than 40 h per week. According to the NCES, 36% of for-profit students are employed while 27% and 18% of public and nonprofit, respectively, are employed full-time. Almost twice as many students employed by the military attend for-profit universities. Attending college online is easier virtually if you have work and family responsibilities. Perhaps, caffeine is used to maintain alertness/cognitive function as the demands of life increase over the lifespan, for example, work and family responsibilities and attending school.

There are a variety of reasons people consume ED. In our study, school or schoolwork, work, competition or event, and the need for more energy were the main situations selected by our heaviest drinkers (>10/month). Malinauskas et alCitation20 found 67% of their participants used ED due to lack of sleep, 65% consumed ED to increase energy, and 54% mixed energy drinks with alcohol. Other researchers have found that people consume ED to compensate for lack of sleep, remain alert to study for an exam or work on a project tCitation20, and mix with liquor.Citation10,Citation20,Citation23,Citation24

A variety of side effects, including increased blood pressure, insomnia, a lack of sleep, poor sleep quality, nervousness, jitters, anxiety, dizziness, gastrointestinal pain, heart palpitations, and allergic reactionsCitation37, have been associated with ED. Our subjects’ most common side effects, headaches and speeding, were reported by those who drank >10 per month. Previous interventional studies have reported inter-individual differences in the type of side-effects reported by individuals with ED consumption.Citation38 However, since our study was a cross-sectional study, we were unable to elucidate inter-individual differences in ED responses.

Frequent drinkers consumed ED when they lacked sleep. Using a stimulant, such as caffeine, to avoid sleeping can have adverse health effects.Citation39 In addition, lack of sleep and poor-quality sleep can slow an individual’s cognitive function Citation40 and have been linked to other health outcomes, such as obesity.Citation41 Yet, many users consume ED because they lack sleep but drinking energy drinks can inhibit sleep.Citation42

ED consumption presumably increases cognitive performance, mood, energetic feelings, and productivity, potentially increasing the likelihood that ED will be misused or abused. Caffeine is the primary stimulant in ED and may be addictive. A typical ED caffeine content ranges from 2 mg/fl oz to 90 mg/fl oz, where concentrated caffeine energy shots can range from 3 mg/fl oz to 500 mg/fl oz (https://www.caffeineinformer.com/the-caffeine-database) Citation43. It is known that regular consumption of caffeinated beverages, i.e., ED, can lead to greater consumption of these drinks as consumers try to maintain the same energy rush and enhanced benefits. The escalating consumption can lead to long-term and more adverse health problems, ranging from minor (such as dehydration or light-headedness) to major (such as renal failure, stroke, cardiorespiratory distress, and even death).Citation21 The World Health Organization recognizes "caffeine use disorder" as a clinical disorder.Citation44 Some of our subjects may have been addicted to ED. One subject drank 6 cans a day, 9 consumed more than 1 per day, but less than 6, 11 consumed one can per day. Only the subjects who consumed more than 10 drinks per month reported experiencing adverse side effects suggesting they may have become habituated to caffeine despite side effects.

Some of our frequent ED drinkers combined ED and alcohol when partying. ED combined with alcohol can lead to other risky behaviors.Citation45 Risky behaviors include impaired driving; prescription medication, illicit drug use and mixing substances; tobacco use; engaging in physical altercations; high-risk sexual activities (unprotected sex or nonconsensual sexual encounters); binge drinking leading to alcohol dependence; and other criminal behaviors.Citation8,Citation10,Citation11,Citation23,Citation46,Citation47 We did not ask about these risky behaviors, but our participants did combine alcohol with one ED on average when they partied.

Overuse or dependence on ED as an addiction is yet to be substantiated with qualitative data. Based on the DSM-IV criteria for evaluating substance dependenceCitation17, only a small percentage of caffeine users would likely meet the criteria for caffeine dependence, it can be subjectively believed that dependence may exist based on individual claims of experiencing withdrawal symptoms.Citation17 For example, in one study, 11% of 6778 participants stated they had experienced withdrawals. Still, even in that capacity, there are debates about whether caffeine is strong enough to cause addiction.Citation17

ED use has been paired with physical activity. Many athletes drink ED to improve sports performance.Citation21,Citation22 While our subjects were not trained athletes, more than 60% were associated with the military, requiring a minimum fitness level. We did not find ED use was associated with physical activity except when it was vigorous. We do not know if ED were used to enhance performance or to recover after a workout.

Our study had several potential limitations. First, the population may not represent all online students; for example, a greater percentage of our students were associated with the military than the general population. Second, the survey was administered online, which is known to have a lower response rate than alternative modes, such as in-person, like the study reported by Malinauskas et al.Citation20 Although online questionnaires are commonplace, our response rate was lower than expected.Citation48 We sent one email and did not follow up with a second email to encourage more students to complete the survey. Also, we do not know how many people opened and read the email; perhaps that rate is low for our student population. Although we had a low response rate, for the purposes of our study, the models in our findings were sufficiently powered and significant even with stringent criteria for controlling for Type I and Type II errors.

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first reporting ED use by students attending an online university. This study suggests more online students consume ED in a similar pattern and for the same reasons as in-person college students. The side effects experienced by our online group are similar to those reported in other studies of college students, with the most common being headaches. Caffeine is the most commonly used drug worldwideCitation49, the primary stimulant in EDs, and EDs are among the most rapidly growing markets. The long-term impacts of ED consumption on a public health scale remain to be fully understood. In conclusion, we found that more online students drink EDs than younger students attending in-person learning institutions but for the same reasons. Despite different lifestyles, there still appears to be a need to meet daily obligations with an energy stimulant.

Conclusions

Energy drink usage was explored at an online university. The participants consumed ED in part to help them stay awake to study but also in a variety of other life situations similar to students who attend in-person learning universities. Therefore, a greater awareness is needed, perhaps by means of public education, policy implementation, public health proclamations, or the like that address issues concerning energy drink consumption in college students.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of USA and received approval from the Institutional Review Board at American Public University System.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Stefany Primeaux for her review of the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Nadeem IM, Shanmugaraj A, Sakha S, Horner NS, Ayeni OR, Khan M. Energy drinks and their adverse health effects: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Health. 2021;13(3):265–277. doi:10.1177/1941738120949181.

- Sports LR, Drinks E. Global Market Trajectory & Analytics. 2020. https://www.researchandmarkets.com/reports/338469/sports_and_energy_drinks_global_market?utm_source=BW&utm_medium=PressRelease&utm_code=97rz6m&utm_campaign=1436156±-±%2493.2 ± Billion ± Sports ± and ± Energy ± Drinks ± Market±-±Global ± Trajectory±%26 ± Analytics ± Report ± 2020-2027&utm_exec = chdo54prd

- Buchanan L, Yeatman H, Kelly B, Kariippanon K. Digital promotion of energy drinks to young adults is more strongly linked to consumption than other media. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2018;50(9):888–895. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2018.05.022.

- LeDuc D. Who is generation Z: The Pew Charitable Trusts; 2019 [cited 2022 July 1]. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/trust/archive/spring-2019/who-is-generation-z

- Pollack CC, Kim J, Emond JA, Brand J, Gilbert-Diamond D, Masterson TD. Prevalence and strategies of energy drink, soda, processed snack, candy and restaurant product marketing on the online streaming platform Twitch. Public Health Nutr. 2020;23(15):2793–2803. doi:10.1017/S1368980020002128.

- Auxier B, Anderson M. Social media use in 2021: Pew Research Center: Internet, Science & Tech.; 2022 [cited 2022 June 29]. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/04/07/social-media-use-in-2021/

- Reportlinker.Com. United States Energy Drink Market - Growth, Trends, and Forecasts (2020–2025). 2020.

- Kraak VI, Davy BM, Rockwell MS, Kostelnik S, Hedrick VE. Policy recommendations to address energy drink marketing and consumption by vulnerable populations in the United States. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2020;120(5):767–777. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2020.01.013.

- Health NNCfCaI. Energy Drinks: National Insitutes of Health; 2018 [updated July 2018]. https://www.nccih.nih.gov/health/energy-drinks

- Spierer DK, Blanding N, Santella A. Energy drink consumption and associated health behaviors among university students in an urban setting. J Community Health. 2014;39(1):132–138. doi:10.1007/s10900-013-9749-y.

- Ishak WW, Ugochukwu C, Bagot K, Khalili D, Zaky C. Energy drinks: psychological effects and impact on well-being and quality of life-a literature review. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2012;9(1):25–34.

- B, Ua RIA, Reaching Others w E D R, U, at Buffalo. 2011. http://www.buffalo.edu/cria/news_events/es/es1.html

- Boolani A, Fuller DT, Mondal S, Wilkinson T, Darie CC, Gumpricht E. Caffeine-containing, adaptogenic-rich drink modulates the effects of caffeine on mental performance and cognitive parameters: a double-blinded, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Nutrients 2020;12(7):1922–1942. doi:10.3390/nu12071922.

- Heckman M, Sherry K, Gonzalez de Mejia E. Energy drinks: an assessment of their market size, consumer demographics, ingredient profile, functionality, and regulations in the United States. Compr Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2010;9(3):303–317. doi:10.1111/j.1541-4337.2010.00111.x.

- Roy A, Deshmukh R, Energy Drinks Market Size, Share, Demand. | Industry Analysis 2026: Allied Market Research; 2019. https://www.alliedmarketresearch.com/energy-drink-market

- Booth N, Saxton J, Rodda SN. Estimates of caffeine use disorder, caffeine withdrawal, harm and help-seeking in New Zealand: a cross-sectional survey. Addict Behav. 2020;109:106470. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106470.

- Persad LA. Energy drinks and the neurophysiological impact of caffeine. Front Neurosci. 2011;5(116):1–8.

- Haynie D. Younger Students Increasingly Drawn to Online Learning, Study Finds. 2015. https://www.usnews.com/education/online-education/articles/2015/07/17/younger-students-increasingly-drawn-to-online-learning-study-finds

- United Nations. Policy Brief: Education during COVID-19 and beyond. New York: United Nations; 2020 [updated July 1, 2022]. https://unsdg.un.org/sites/default/files/2020-08/sg_policy_brief_covid-19_and_education_august_2020.pdf.

- Malinauskas BM, Aeby VG, Overton RF, Carpenter-Aeby T, Barber-Heidal K. A survey of energy drink consumption patterns among college students. Nutr J. 2007;31(6):35. doi:10.1186/1475-2891-6-35.

- Bulut B, Beyhun NE, Topbas M, Can G. Energy drink use in university students and associated factors. J Community Health. 2014;39(5):1004–1011. doi:10.1007/s10900-014-9849-3.

- Buxton C, Hagan JE. A survey of energy drinks consumption practices among student -athletes in Ghana: lessons for developing health education intervention programmes. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2012;9(1):9.

- Brache K, Stockwell T. Drinking patterns and risk behaviors associated with combined alcohol and energy drink consumption in college drinkers. Addict Behav. 2011;36(12):1133–1140. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.07.003.

- Oglesby LW, Amrani KA, Wynveen CJ, Gallucci AR. Do energy drink consumers study more? J Community Health. 2018;43(1):48–54. doi:10.1007/s10900-017-0386-8.

- Da D. DATAUSA: DATAUSA; 2022 [cited 2022]. https://datausa.io/profile/university/american-public-university-system#about

- University AP. APUS Fast Facts: Student Profile; 2020. http://www.apus.edu/about-us/facts.htm

- Marczinski C. Alcohol mixed with energy drinks: Consumption patterns and motivations for use in US college students. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8:3232–3245. doi:10.3390/ijerph8083232.

- Craig CL, Marshall AL, Sjostrom M, et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2003;35(8):1381–1395. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000078924.61453.FB.

- Chernoff H. Large-Sample Theory: Parametric Case. The Annals of Mathematical Statistics. 1956;27(1):1–22. doi:10.1214/aoms/1177728347.

- Lehmann EL. Elements of Large-Sample Theory. New York: Springer; 2004.

- Li A, Barber RF. Multiple testing with the structure-adaptive Benjamini–Hochberg algorithm. J R Stat Soc: Ser B (Stat Methodol). 2019;81(1):45–74. doi:10.1111/rssb.12298.

- Arbiet C, Horn L. A profile of the enrollment patterns and demographic characteristics of undergraduates at for-profit institutions. US Dept of Education; 2017.

- Planning Committee for a Workshop on Potential Health Hazards Associated with Consumption of Caffeine in Food and Dietary Supplements; Food and Nutrition Board; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Caffeine in Food and Dietary Supplements: Examining Safety: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US); 2014.

- Lieberman HA, Fulgoni VL, III. Daily patterns of caffeine intake and the association of intake with multiple sociodemographic and lifestyle factors in US adults based on the NHANES 2007-2012 surveys. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2019;119(1):106–114. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2018.08.152.

- Park SO, Blanck HM, Sherry B. Characteristics associated with consumption of sports and energy drinks among US adults: National Health Interview Survey. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2013;113(1):112–119. doi:10.1016/j.jand.2012.09.019.

- Berger LK, Fendrich M, Chen HY, Arria AM, Cisler RA. Sociodemographic correlates of energy drink consumption with and without alcohol: results of a community survey. Addict Behav. 2011;36(5):516–519. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.12.027.

- Kallmyer T. Energy Drink Side Effects: Caffeine Informer; 2019. https://www.caffeineinformer.com/energy-drink-side-effects

- Fuller DT, Smith ML, Boolani A. Trait energy and fatigue modify the effects of caffeine on mood, cognitive and fine-motor task performance: a post-hoc study. Nutrients 2021;13(2):412–436. doi:10.3390/nu13020412.

- Itani OJ, Watanabe N, Kaneita Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: a systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2017;32:225–246. doi:10.1016/j.sleep.2016.08.006.

- O’Callaghan FM, Reid N. Effects of caffeine on sleep quality and daytime functioning. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. 2018;11:263–271. doi:10.2147/RMHP.S156404.

- Al Khatib HH, Darzi J, Pot GK. The effects of partial sleep deprivation on energy balance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2017;71(5):614–624. doi:10.1038/ejcn.2016.201.

- Watson EC, Kohler M, Banks S. Caffeine consumption and sleep quality in Australian adults. Nutrients 2016;4(8):479. doi:10.3390/nu8080479.

- Informer C. Caffeine Content of Drinks; 2021. https://www.caffeineinformer.com/the-caffeine-database

- Meredith S, Juliano L, Hughes J, Griffiths R. Caffeine use disorder: a comprehensive review and research agenda. J Caffeine Res. 2013;3(3):114–130. doi:10.1089/jcr.2013.0016.

- Marczinski CF. Energy drinks mixed with alcohol: what are the risks? Nutr Rev. 2014;Suppl 1(1):98–107. doi:10.1111/nure.12127.

- Higgins JP, Tuttle TD, Higgins CL. Energy beverages: content and safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(11):1033–1041. doi:10.4065/mcp.2010.0381.

- Luneke AC, Glassman TJ, Dake JA, Blavos AA, Thompson AJ, Kruse-Diehr AJ. Energy drink expectancies among college students. J Am Coll Health. 2020;Jul(16):1–9.

- Lallukka T, Pietilainen O, Jappinen S, Laaksonen M, Lahti J, Rahkonen O. Factors associated with health survey response among young employees: a register-based study using online, mailed and telephone interview data collection methods. BMC Public Health. 2020;20(1):184. doi:10.1186/s12889-020-8241-8.

- Ferre S. Caffeine and substance use disorders. J Caffeine Res. 2013;3(2):57–58.