Abstract

Objective: To assess the frequency of preventative COVID-19 behaviors and vaccination willingness among United States (US) college and university students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Participants: Participants (N = 653) were ≥18 years old and students at institutions for higher education in the US in March 2020. Methods: Students self-reported preventative behaviors, willingness to be vaccinated, and social contact patterns during four waves of online surveys from May-August 2020. Results: Student engagement in preventative behaviors was generally high. The majority of students intended to be vaccinated (81.5%). Overall, there were no significant differences in the proportion adopting preventative behaviors or in willingness to be vaccinated by sex or geographic location. The most common reason for willingness to get vaccinated was wanting to contribute to ending COVID-19 outbreaks (44.7%). Conclusions: Early in the pandemic, college students primarily reported willingness to vaccinate and adherence to preventative behaviors. Outreach strategies are needed to continue this momentum.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic, caused by the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, resulted in unprecedented disruption to society globally. Population-wide disease mitigation measures such as social distancing, school and business closures, and stay-at-home orders were undertaken at varying levels across the United States.

The COVID-19 pandemic led to significant behavioral changes due to government mandated policies and public health recommendations. While policies have changed over time to match emerging scientific evidence, individual-level non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) have included social distancing and other preventative measures, including the use of masks or face coverings and handwashing, which may all help curb the spread of COVID-19 to various degrees. Vaccination has also emerged as a significant preventative measure now that vaccines against COVID-19 are available to the general public in the United States. These types of preventative behaviors can provide individual- and population-level benefits and prevent the transmission of COVID-19.Citation1

The lives of students at institutes of higher education were uniquely impacted as colleges and universities closed their campuses and migrated to virtual learning platforms in accordance with mitigation measures beginning in spring of 2020. As colleges and universities reopened, the increased density and mixing of students impacted disease dynamics on campuses and in surrounding communities in ways that are often difficult to predict and control.Citation2–4 Multiple factors can place colleges and universities at higher risk for the spread of infectious diseases, including a large number of students living and studying in close quarters and engaging in activities that can lead to transmission, such as going to bars, restaurants or congregating in other settings.Citation5,Citation6 As of July 2021, the college-aged cohort (18–39 years) also had the lowest proportion of individuals vaccinated or intending to get vaccinated of any age group in the US.Citation7 Young adults are also more likely to have asymptomatic or only mild COVID-19 infections compared to older age groups, which can allow the virus to spread undetected.Citation8–11 Asymptomatic individuals can transmit COVID-19, which may impede the identification of transmission chains among young adults.Citation9,Citation12 For these reasons, college and university students are an important group to consider for COVID-19 prevention and control.

It is necessary to evaluate vaccine willingness and adherence to other preventative behaviors to improve COVID-19 mitigation strategies and messages for individual protection and community disease control. NPI adherence is particularly important for college and university students as many colleges and universities resume in-person classes, sports, and activities and allow students to return to living on campus.

The objective of this paper is to assess a range of COVID-19 preventative behaviors (e.g., handwashing, mask use, reduction of social contacts) and intentions (e.g., vaccination willingness) among a sample of students enrolled in higher education in the United States during the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic to inform the development of COVID-19 mitigation strategies for this population.

Materials and methods

Survey

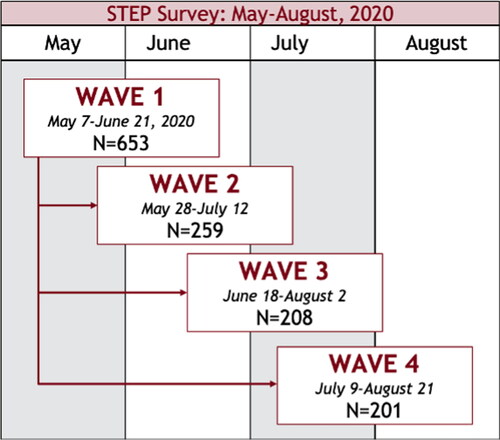

We conducted a series of online surveys between May 7th, 2020 and August 21st, 2020. The first survey (wave 1) was available between May 7th–June 21st, and participants were invited to complete up to 3 additional surveys (). Each participant had the opportunity to complete up to 4 surveys in total through August 21, 2020.

Participants

Potential participants were made aware of the survey through outreach via social media (i.e., Twitter and Facebook), email, and word-of-mouth. Individuals were eligible to participate if they were at least 18 years of age at the time they took the wave 1 survey and were enrolled as a student at an institution for higher education in the United States in the month of March 2020. Participants self-reported their sex assigned at birth, age, race, and their residential location at the time of the survey (urban, suburban, or rural).

Vaccination intention

In waves 1 and 4, participants reported on a 5-point Likert scale how likely they would be to get a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine once one was available (very unlikely, somewhat unlikely, uncertain, somewhat likely, very likely). In wave 4, participants who reported they were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” were then asked to select the primary reason they would choose to get a COVID-19 vaccine from a list of options (I want to protect myself, I want to protect my family and loved ones, I am concerned about COVID-19 in general, I want to contribute to ending COVID-19 outbreaks, my doctor or other health care professional recommends vaccines, other). Participants who reported they were “very unlikely,” “somewhat unlikely,” or “uncertain” were then asked to select the primary reason they would not choose to get a COVID-19 vaccine (I am not concerned about COVID-19 in general, I am not concerned about getting COVID-19 myself, I am concerned about the safety of the vaccine, I am concerned about how well the vaccine will protect, I am concerned about the cost of the vaccine, I don’t like needles, other).

Hygiene and mask use

In wave 1 (May-June 2020), participants were asked to recall a typical week in January 2020 and self-report how often (less than once, 1–3 times, 4–7 times, more than 7 times) they washed their hands with soap and water, used hand sanitizer, and cleaned their home with household cleaning products. Participants reported how often they performed these behaviors in the past week as compared to January 2020 (less, about the same, somewhat more, a lot more). Participants also reported how often they wore a mask indoors and outdoors (never, sometimes, often, all the time) in the past week.

Social distancing

In each wave, participants were asked to report how much they agreed or disagreed with a series of statements about social distancing (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree). In the survey, we defined social distancing, also known as physical distancing, based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) definition: “keeping space between yourself and other people outside of your home”Citation13 and we further defined that to practice social distancing means to stay at least 6 feet from other people, to not gather in groups of people, and to stay out of crowded spaces. In waves 3 and 4, participants were also asked to report to what extent they followed the recommendations for social distancing in the past two weeks.

Social contact patterns

In wave 1, respondents were asked to recall a typical week in Fall 2019 and report the total number of people living in their household, the number of older adults (>65 years of age) living in their household, the total number of non-household contacts (defined as ≥ 15 minutes of close contact with people not living in the household), and the number of older adult non-household contacts. In wave 1, participants also reported the total number of people and the number of older adults living in their household in March 2020. In each wave, participants estimated the total number of non-household contacts and older adult non-household contacts in the past week.

Statistical analysis

A respondent was included in the analytic sample if they provided an answer to at least one of the survey questions included in our analysis. We describe the demographic characteristics collected in the wave 1 survey (N, % or mean, SD) of the analytic sample. Analyses were done using R version 1.3.1073.

We summarize adherence to mask-wearing and willingness to get vaccinated by sex and geographic area (i.e., urban, suburban, or rural) participants resided at the time of the survey. We report the frequency of self-reported preventative behaviors in January 2020 compared to the frequency reported during the pandemic based on responses to the wave 1 survey using Pearson’s Chi-squared test. 95% confidence intervals (CIs) are calculated using the Normal approximation to the binomial and reported, and p values less than 0.05 were considered significant. We report the association between the above demographic characteristics and change over time in preventative behaviors in response to the pandemic.

We describe the proportion of participants who report various levels of willingness to get vaccinated against COVID-19, the proportion of respondents who report various degrees of agreement and disagreement with statements regarding social distancing, and the proportion who report following social distancing recommendations. We summarize the median and interquartile range (IQR) for the number of household members and social contacts in Fall 2019 and in each of the waves of the survey.

Institutional review board

This study was determined to be exempt by the University of Minnesota IRB.

Results

Sample

In total, 740 individuals clicked to open the link to the wave 1 online survey. 653 completed at least one of the survey questions included in our analysis. Ninety-five percent of our study population was aged 18–33 years (). 79.9% of our population was female, and 63.8% identified as white or Caucasian.

Table 1. Demographics: Wave 1 (May 7–June 21, 2020).

Vaccination intention

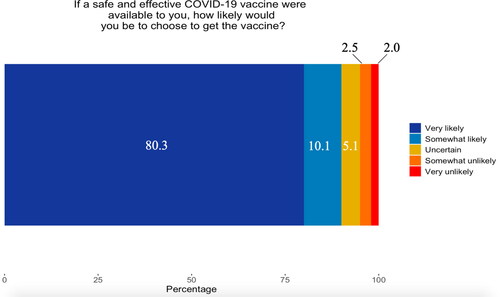

In wave 1, 81.5% (95% CI: 78.4, 84.7) reported being “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to get a COVID-19 vaccine once one was available if it were safe and effective. 11.9% (95% CI: 9.3, 14.5) reported being “uncertain,” and 6.6% (95% CI: 4.6, 8.6) reported being “somewhat unlikely” or “very unlikely” to get a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine once one was available. Willingness to get vaccinated was also measured in wave 4 (). Similar proportions of women [81.8%, (95% CI: 78.3, 85.3)] and men [80.3%, (95% CI: 73.1, 87.5)] reported being “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to get a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine once one was available. A slightly higher proportion of participants living in either suburban or rural areas [83.8%, (95% CI: 79.6, 88.1)] reported being “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to get a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine once one was available compared to participants living in urban areas [78.3%, (95% CI: 73.6, 83.0)].

Figure 2. Percentages of self-reported willingness to get vaccinated with an available safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine in wave 4 (July 9–August 21, 2020).

In wave 4, the most common primary reasons for willingness to get vaccinated reported by participants who were “somewhat likely” or “very likely” to get a COVID-19 vaccine were “I want to contribute to ending COVID-19 outbreaks” [44.7%, (95% CI: 37.4, 52.0)] and “I want to protect my family and loved ones” [25.7%, (95% CI: 19.3, 32.1)]. The most common primary reasons to be unwilling to get vaccinated reported by participants who were “uncertain,” “somewhat unlikely,” or “very unlikely” to get a COVID-19 vaccine were “I am concerned about the safety of the vaccine” [63.2%, (95% CI: 41.5, 84.8)] and “I am concerned about how well the vaccine will protect” [15.8%, (95% CI: −0.6, 32.2)] ().

Table 2. Primary reasons for and against willingness to vaccinate against COVID-19 (N,%) by likelihood of vaccination: July 9–August 21, 2020 (wave 4, N = 198).

Hygiene and mask use

In wave 1, participants reported that prior to the pandemic (January 2020) the following hygiene behaviors were observed more than seven times per week: 79.6% washed their hands with soap and water, 17.8% used hand sanitizer, and 10.1% cleaned their home with household cleaning products. Nearly half (47.0%) reported washing hands with soap and water, 44.0% using hand sanitizer, and 22.7% cleaning their home with household cleaning products “somewhat more” or “a lot more” compared to an average week in January 2020 ().

Table 3. Hygiene behaviors: Wave 1 (May 7–June 21, 2020).

A similar proportion of men and women (81.0% and 79.0%, respectively) self-reported washing hands with soap and water and using hand sanitizer (72.4% and 70.2%, respectively) “somewhat more” or “a lot more” than in January 2020. Although a higher proportion of women (65.7%) compared to men (59.5%) reported increasing cleaning the home “somewhat more” or “a lot more” than in January 2020, the difference was not statistically significant. A higher proportion of participants living in urban areas self-reported handwashing, using hand sanitizer, and cleaning the home “somewhat more” or “a lot more” than in January 2020 compared to suburban and rural areas, but the difference was not statistically significant.

The proportion of participants who reported wearing masks indoors “often” or “all the time” generally increased across all waves of the survey for both sexes and for both urban/suburban and rural locations (). In wave 1, 77.3% (95% CI: 73.4, 81.1) of women said they wore masks “often” or “all the time” while in public indoors, compared to 70.1% of men (95% CI: 61.8, 78.4). 57.5% (95% CI: 53.0, 62.0) of women and 59.0% (95% CI: 50.1, 67.9) of men said they wore masks “often” or “all the time” while in public outdoors. Participants living in urban or suburban areas at the time of the survey were more likely to wear masks indoors “often” or “all the time” than participants living in rural areas across all waves of the survey.

Table 4. Mask use by demographics, by wave.

Social distancing

In wave 1, 92.9% (95% CI: 90.8, 95.0) of participants agreed or strongly agreed social distancing was necessary for them, which increased to 94.5% (95% CI: 91.7, 97.3), 95.0% (95% CI: 92.0, 98.0), and 97.5% (95% CI: 95.3, 99.7) in waves 2, 3, and 4, respectively. In wave 1, the vast majority agreed or strongly agreed social distancing was necessary for older adults [98.3%, (95% CI: 97.3, 99.3)], for people with underlying health conditions [98.3%, (95% CI: 97.3, 99.3)], and in areas of the country with large outbreaks [98.0%, (95% CI: 96.8, 99.1)]. These proportions remained consistent in each subsequent study wave. 90.6% (95% CI: 86.6, 94.6) and 94.5% (95% CI: 91.3, 97.6) reported “very closely” or “somewhat closely” following the recommendations for social distancing in waves 3 and 4, respectively.

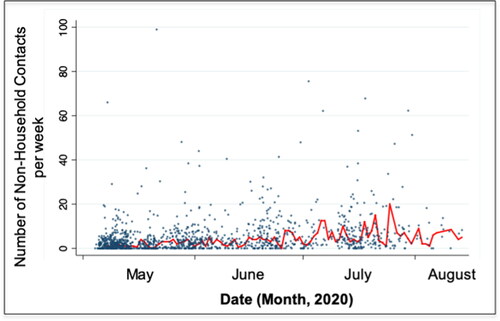

Social contact patterns

When asked to recall Fall of 2019, participants estimated a median of 30 (IQR: 10–60) total non-household contacts per week and 2 (IQR: 0–5) non-household older adult contacts per week. Compared to Fall 2019, total non-household contacts were significantly decreased with participants reporting that the median number of total non-household contacts in the past week was 1 (IQR: 0–3), 2 (IQR: 1–6), 5 (IQR: 2–10) and 5 (IQR: 2–10) in waves 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively (). The number of non-household older adult contacts was 0 (IQR: 0) at baseline and remained below 1 at all follow-up surveys.

Discussion

Our study examined the prevalence of behaviors intended to prevent and control COVID-19 including vaccination willingness, performing hygiene behaviors, wearing masks, and social distancing for COVID-19 among college and university students at multiple time points early on during the COVID-19 pandemic (May–August, 2020). In our sample, we found the self-reported willingness to receive a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine, adherence to mask-wearing and hygiene behaviors was high, with no significant difference between sexes and urban, suburban, or rural residents. We found participants generally agreed with and reported following social distancing recommendations, but the number of non-household contacts increased over time.

Despite a majority of participants in this study reporting that they were "somewhat likely” or “very likely” to receive a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccination, the college and university-aged cohort remains below the target level of COVID-19 vaccine coverage. As of July 2021, the young adult population in the US (age 18-39) had the lowest vaccination coverage when compared to other age groups,Citation7 which may have been due, in part, to the phased vaccine eligibility. However, with continuing sub-optimal levels of vaccination in this age group, additional preventative measures may still be needed to effectively prevent outbreaks in the college and university age group. In our study, we found the most common reasons for wanting to get a safe and effective COVID-19 vaccine were wanting to help end COVID-19 outbreaks and to protect family and loved ones; these reasons could become messages that would appeal to other young adults and could be the target of public health messaging about COVID-19 vaccination in order to increase vaccination coverage among students.

A similar study that surveyed a national population of college students aged 18–22 in April 2020 found 55% of participants had attended in-person gatherings of 2–9 people outside their household since March 1, 2020,Citation14 and about three-quarters of participants reported compliance with CDC-recommended social distancing measures and most followed suggested hygiene guidelines (if incompletely). Only about half of participants always wore a face mask in public.Citation12 Similarly, we found that the performance of hygiene behaviors has overall increased, although we found higher levels of mask-wearing in participants (77% of women and 70% of men reported wearing masks often or all the time while in public indoors).

Demographics such as gender and age have already been found to influence engagement in hand hygiene and mask-wearing behaviors.Citation15 Engagement in preventative behaviors by the student population is important, as colleges and universities can also impact the surrounding population. For example, following a 62.7% increase in COVID-19 incidence in 18 to 22-year-olds between August 2–29, 2020, a survey of colleges in September 2020 found that counties with a college student population of at least 10% reported an increase in COVID-19 cases compared to counties with a smaller student population.Citation16

We found that from May-August 2020 the proportion of participants who reported wearing masks indoors “often” or “all the time” (compared to “sometimes” or “never”) increased overall across all waves of the survey for all demographic groups. Surveys of American adults have found mask-wearing is also partisan and geographically influenced, although self-reported compliance is typically around 80%.Citation17 Studies outside of the US have also found moderate rates of compliance in preventative behaviors in adolescents.Citation18,Citation19 However, the compliance levels of young adults during the early months of the COVID-19 pandemic – in particular college and university students – were still primarily unknown prior to this survey.

Social distancing is also a highly effective method to reduce transmission, but strict measures such as complete lockdown are not sustainable for an extended period of time. We observed in our sample that the number of in-person contacts increased significantly over the summer months; however, the number of contacts did not reach pre-pandemic levels during the survey period. Unfortunately, as people experience quarantine fatigue, gatherings with non-household members threaten to undo the gains that can be made by following social distancing rules and regulations. The reduction in preventative behavior engagement over time emphasizes the importance of continued clear risk reduction communication.

While willingness to engage in preventative behaviors was generally high for our sample of college and university students at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, participation in preventative behaviors that limited social interactions, such as reducing in-person gatherings, steadily waned over time. There is an urgent need for formal recommendations and guidance for “safer socializing” to offer harm reduction strategies and provide the tools needed to help the general public, including college- and university-aged individuals, differentiate between low-risk and high-risk activities. In future pandemics and/or future waves of the COVID-19 pandemic, the duration of adherence to recommended but socially restrictive preventative behaviors may even be shorter due to fatigue in college and university student populations after SARS-CoV-2-related restrictions. Thus, further research into how behavioral choices align or fail to align with public health recommendations is needed both for the COVID-19 pandemic and to establish a toolkit for mitigating the impact of pandemics and other disease threats in the future.

To our knowledge, this is one of the first studies to assess the preventative health behaviors of college and university students over time during the initial phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. However, this study is not without limitations. Our survey demographics were skewed as participants were primarily white and female. This study drew a convenience sample of college students, and thus is not intended to be representative of all students at institutes for higher education in the United States. An additional limitation is that at the time of this survey, many college attendees were at home due to school closures or summer break, so this study may not reflect student behavior while on campus. In our survey, we did not differentiate between respirators, procedure masks, or cloth face coverings which offer varying degrees of personal protection and source control. Additionally, vaccines against COVID-19 were not available during our study period, so this study may not reflect participant attitudes about the COVID-19 vaccines that may be currently available to students.

As colleges continue to reopen (and in some cases, experience extensive outbreaks of COVID-19Citation20), additional research needs to be undertaken to determine how adherence to important preventative behaviors such as vaccination and mask-wearing among college attendees has changed compared to adherence at the onset of the pandemic.

Conclusion

Engagement in preventative behaviors against COVID-19 by college and university students was generally high during the first four months of the COVID-19 pandemic. Urban, suburban, and rural environments were associated with different reported frequencies of mask-wearing. Overall, the majority of students reported themselves willing to get vaccinated against COVID-19. Specific strategies for COVID-19 prevention aimed at students are necessary to ensure adherence is maintained throughout the later stages of the pandemic. Comparing early adherence to preventative behaviors to current behaviors in on-campus college and university students is an important next step.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States and received approval from the University of Minnesota.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Moghadas SM, Fitzpatrick MC, Sah P, et al. The implications of silent transmission for the control of COVID-19 outbreaks. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(30):17513–17515. doi:10.1073/pnas.2008373117.

- Benneyan J, Gehrke C, Ilies I, Nehls N. Community and campus COVID-19 risk uncertainty under university reopening scenarios: model-based analysis. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2021;7(4):e24292. doi:10.2196/24292.

- Pray IW, Kocharian A, Mason J, Westergaard R, Meiman J. Trends in outbreak-associated cases of COVID-19 – Wisconsin, March-November 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4):114–117. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a2.

- Fox MD, Bailey DC, Seamon MD, Miranda ML. Response to a COVID-19 outbreak on a University Campus – Indiana, August 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(4):118–122. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7004a3.

- Sami S, Turbyfill CR, Daniel-Wayman S, et al. Community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 associated with a local bar opening event – Illinois, February 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(14):528–532. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7014e3.

- Guy GP, Jr., Lee FC, Sunshine G, et al. Association of state-issued mask mandates and allowing on-premises restaurant dining with county-level COVID-19 case and death growth rates – United States, March 1-December 31, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(10):350–354., doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7010e3.

- Baack BN, Abad N, Yankey D, et al. COVID-19 vaccination coverage and intent among adults aged 18-39 years – United States, March-May 2021. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2021;70(25):928–933. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7025e2.

- He G, Sun W, Fang P, et al. The clinical feature of silent infections of novel coronavirus infection (COVID-19) in Wenzhou. J Med Virol. 2020;92(10):1761–1763. doi:10.1002/jmv.25861.

- Huang L, Zhang X, Zhang X, et al. Rapid asymptomatic transmission of COVID-19 during the incubation period demonstrating strong infectivity in a cluster of youngsters aged 16-23 years outside Wuhan and characteristics of young patients with COVID-19: a prospective contact-tracing study. J Infect. 2020;80(6):e1–e13. doi:10.1016/j.jinf.2020.03.006.

- Liao J, Fan S, Chen J, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of COVID-19 in adolescents and young adults. Innovation (Camb). 2020;1(1):100001. doi:10.1016/j.xinn.2020.04.001.

- Gandhi M, Yokoe DS, Havlir DV. Asymptomatic transmission, the Achilles’ Heel of current strategies to control Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(22):2158–2160. doi:10.1056/NEJMe2009758.

- Dowd JB, Andriano L, Brazel DM, et al. Demographic science aids in understanding the spread and fatality rates of COVID-19. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(18):9696–9698. doi:10.1073/pnas.2004911117.

- National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (NCIRD) DoVD. Social Distancing. In: Services USDoHH, editor.: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2020.

- Cohen AK, Hoyt LT, Dull B. A descriptive study of COVID-19-related experiences and perspectives of a national sample of college students in Spring 2020. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(3):369–375. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.06.009.

- Lee M, You M. Psychological and behavioral responses in South Korea during the early stages of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(9):2977.

- Walke HT, Honein MA, Redfield RR. Preventing and responding to COVID-19 on college campuses. JAMA. 2020;324(17):1727. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.20027.

- Josh Katz MS-K, Kevin Quealy. A detailed map of who is wearing masks in the U.S. The New York Times, July 17, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2020/07/17/upshot/coronavirus-face-mask-map.html. Accessed August 14, 2020.

- Guzek D, Skolmowska D, Glabska D. Analysis of gender-dependent personal protective behaviors in a national sample: polish adolescents’ COVID-19 experience (PLACE-19) study. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5770.

- Chen X, Ran L, Liu Q, Hu Q, Du X, Tan X. Hand hygiene, mask-wearing behaviors and its associated factors during the COVID-19 epidemic: a cross-sectional study among primary school students in Wuhan, China. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(8):2893.

- Reilly K. Coronavirus outbreaks linked to fraternity houses are a warning for college campuses. TIME USA, July 13, 2020. https://time.com/5865251/coronavirus-fraternities-colleges/. Accessed August 11, 2020.