Abstract

Objective: The current study examined associations between grandiose and vulnerable subclinical narcissistic traits and alcohol use among college students and whether drinking motives mediated these associations.

Methods and Participants: Young adult college students who reported past month alcohol use were invited to complete self-report online surveys (N = 406; 81% female; Mage = 20.13, SD = 1.69; 10% Hispanic; 85% White).

Results: Results from path analysis using structural equation modeling indicated that there were no direct associations between grandiose or vulnerable subclinical narcissistic traits and alcohol use. However, several drinking motives mediated these associations. Specifically, the association between grandiose traits and alcohol use was mediated by enhancement and social motives. Similarly, the association between vulnerable traits and alcohol use was mediated by enhancement, social and coping motives.

Conclusions: Findings highlight a potential mechanism by which personality traits may contribute to a health risk behavior among young people.

According to the 2022 National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), 67.9% of people ages 18–25 reported they drank alcohol in the past year, and 50.2% reported they drank in the past month.Citation1 College students seem to be particularly at risk as they are routinely exposed to factors that foster alcohol use, such as a campus culture promoting drinking.Citation2,Citation3 Indeed, over half of full-time students report past-month alcohol use,Citation1 with 12.4% consuming more than 10 drinks on an occasion.Citation4 Alarmingly, 1,519 college students aged 18-24 die annually from accidental alcohol-related injuries.Citation5 By sophomore year, nearly all students report having the opportunity to try alcohol, making it one of their earliest exposed substances in this context.Citation6 Gender differences in alcohol consumption have narrowed in recent decades, but most female and male college students still report use.Citation7 Indeed, self-reported past-month use among collegiate females (51.8%) may exceed males (45.7%),Citation1 emphasizing concern for the increased risk of alcohol-related problems by comparison.Citation7 Understanding the factors that impact this health risk behavior are important for prevention efforts among this population.

Narcissism

Narcissism, a personality characteristic in Cluster B, is generally characterized by grandiose sense of self-importance, perceived entitlement or superiority, a need for admiration, and lacking empathy.Citation8 However, scholars have argued narcissism is best understood through a dimensional lensCitation9 and suggest that there are two distinct constructs of narcissism: grandiosity and vulnerability. Although grandiose and vulnerable narcissism share overlapping features, such as entitled self-importance, grandiosity is distinguished by assertiveness, whereas narcissistic vulnerability often relates to feelings of inadequacy and positively correlates with neurotic behavioral traits.Citation10

Importantly, although researchers are still exploring how to best identify under what circumstances subclinical narcissism (i.e., indicating the presence of narcissistic traits in individuals who have not met diagnostic criteria for narcissistic personality disorder) transitions into clinical narcissism,Citation11 both clinical and subclinical narcissistic traits have been linked with alcohol use. For example, narcissistic personality disorder is often comorbid with substance use disordersCitation12 and share traits with known risk factors for alcohol use, such as impulsivity and negative affectivity.Citation13–16

Research also indicates that subclinical narcissistic traits are not only increasing among college populations in recent decades,Citation17,Citation18 but are also positively predictive of undergraduate student alcohol use.Citation19,Citation20 Luhtanen and colleaguesCitation21 found that subclinical narcissistic traits positively predicted later alcohol use quantity, heavy drinking occurrences, and negative alcohol related outcomes. Similarly, Kramer and colleaguesCitation22 found a positive association between college students’ subclinical narcissistic traits and negative alcohol-related outcomes and Welker and colleaguesCitation23 found positive associations between subclinical narcissistic grandiosity and vulnerability with college students’ alcohol use and negative alcohol-related outcomes. Overall, extant evidence highlights that subclinical narcissistic traits may play an important role in alcohol use. However, we know less about why these personality facets are associated with engagement in this health risk behavior. Notably, most of these studies are not among recent cohorts of students.

Understanding why narcissism may be linked with alcohol use is particularly important in the college student population as these individuals are in the developmental period of emerging adulthood, which is characterized by, among other things, identity exploration and being relatively self-focused.Citation24 Individuals in this lifespan stage are continuing the work they started in adolescence by developing their understanding of themselves, their identity, and their roles in society. Narcissistic traits have implications for how individuals see themselves and othersCitation25 and may have adverse impacts on these normative developmental tasks and processes. This is especially true as academic experiences can impact self-esteem (e.g., grade expectationsCitation26) and regularly offer opportunities for individuals to reevaluate their understanding of themselves.

Drinking motives

Drinking motives, or an individual’s motivations to engage in alcohol use behaviors,Citation27 may be an important factor that helps explain both alcohol use and the association between personality traits and alcohol use among college students. Drinking motives are generally characterized by source as either internal or external.Citation28 Internal drinking motives (coping or enhancement) directly correspond to affect regulation, while external motives (social or conformity) indirectly correspond to affect regulation through environmental factors. These motives can also be characterized by valence as either positive (enhancement or social) or negative (coping or conformity). Notably, a wealth of evidence suggests that each of these motives are linked with alcohol use, albeit in complicated ways. For example, Choi et al.Citation29 found that social and conformity motives were associated with greater alcohol use frequency. However, although social motives were positively related to alcohol use quantity, conformity motives were negatively related, suggesting that students who drank to “fit in” with others drank more often but in lesser amounts on such occasions. Others have similarly found associations between these motives and college student alcohol use,Citation14,Citation30,Citation31 but evidence is mixed. Citation32

Coping motives also have been linked with college student alcohol use. Some research indicates those who report greater coping drinking motives engage in higher levels of problematic drinkingCitation33 and use more alcohol, especially when considering their alcohol expectancies and internalizing symptoms.Citation34 However, others have not found coping motives to play a role in college students drinking.Citation14,Citation31,Citation35 Conversely, enhancement motives have been more consistently associated with alcohol useCitation14,Citation31,Citation33,Citation36 both cross-sectionally and longitudinally.Citation35

Taken together, the literature on relations between college students drinking motives and alcohol use are complicated as findings are mixed. It is important to note that some studies opted to test certain drinking motives as predictors of alcohol use independentlyCitation29,Citation34 rather than collectively, which may have contributed to the disparate findings across samples. However, given each motive has been identified by prior studies as sharing a positive relation to alcohol use among college students, there is collective support for the idea that all drinking motives share a notable relation to alcohol use.

Personality traits and drinking motives

Few studies have investigated drinking motives in relation to personality traits, particularly narcissistic traits, and alcohol use among college students. However, extant evidence indicates that motives may be a potentially important contributor in this relationship. For example, studies suggest associations between enhancement motives with extraversion and coping motives with neuroticism.Citation37,Citation38 More centrally for this study, internal drinking motives have been shown to mediate the relation between common traits across Cluster B personality traits, such as impulsivity and negative affectivity, and alcohol use among adults 11 years following their undergraduate freshman year.Citation39 Similarly, work by Tragesser and colleagues have found that drinking to cope and enhance among middle-aged adultsCitation40 and drinking to enhance among 18- to 21-year-old college studentsCitation41 partially mediated the relations between Cluster B personality traits and diverse alcohol use behaviors and problems.

Although this past work highlights the potentially important role of drinking motives in the associations between a collection of personality traits and alcohol use, it is limited in several ways. First, this work either examined non-college student populations or a truncated age range of college students. Second, in work on college students, participants were only asked to indicate presence of alcohol use disorder symptoms, rather than typical drinking behaviors. Given that approximately 14% of college students 18–22 meet criteria for an alcohol use disorder whereas more than half of all college students report any alcohol use Citation1, it is important for future studies to incorporate a wider range of alcohol use behaviors to better generalize results about this population. Third, coping and enhancement motives were the only two motives measured. Assessing the full range of associations between drinking motives and alcohol outcomes is important to understand these motives as a potential mechanism. Fourth, the results cannot be universally applied for subclinical traits that comprise Cluster B disorders as each disorder has unique symptom criteria, therefore leaving gaps in our understanding of how drinking motives may play a role in the associations between subclinical narcissistic traits and alcohol use. Understanding these relations may help students recognize how their personality traits and drinking motives can contribute to differences in their alcohol use and related outcomes.

Present study

We investigated the potential mediating role of drinking motives in the associations between subclinical narcissistic traits and alcohol use among college students. Specifically, we ask two research questions. First, how are grandiose and vulnerable narcissism associated with alcohol use among college students? Given research has demonstrated links between these personality characteristics and diverse alcohol use outcomes, we expect positive associations between each and alcohol use. Second, how do social, conformity, enhancement, and coping drinking motives mediate these associations? Given the dearth of research on potential mechanisms between narcissism and alcohol use, we make no formal hypotheses and instead treat this question as exploratory.

Method

Participants

Young adult college students from a large, Midwestern University were invited to participate in this self-report online study. Eligible participants included students who were between the ages of 18 and 24 and had consumed alcohol within the past 30 days (N = 406; 81% female; Mage = 20.13, SD = 1.69; 10% Hispanic; 85% White).

Procedure

Data were collected in October and November 2021. Participants were initially recruited through a research participation sign-up system for students seeking extra credit in psychology classes. Through this system, interested participants were able to access the online survey link and complete it on their own time. This system keeps survey responses anonymous while also tracking study completion for instructors to grant extra credit. After several weeks of data collection through this system, the study was opened to all university undergraduate students aged 18–24 using an undergraduate targeted university wide email which provided a link to the online survey for interested participants to complete on their own time. After providing informed consent, screener questions were used to exclude participants who were not between the ages of 18–24 or had not consumed alcohol in the past month. The anonymous self-report survey took an average of 20–25 min to complete.

Measures

Past-month alcohol use

Two items were used to assess the quantity and frequency of participants’ alcohol consumption. Participants were asked the following: (1) During the past 30 days, how often did you usually have any kind of drink containing alcohol? (2) Think of all the times you have had a drink during the past 30 days. How many alcoholic drinks did you have on a typical day when you drank alcohol? Participants were provided with a drop-down selection of 0–30 to indicate the number of days and drinks within the past 30 days. A quantity X frequency score was calculated to reflect total alcohol consumption with greater scores indicating greater alcohol use. Previous research has used similar quantity and frequency scales to measure alcohol useCitation42 and has demonstrated moderate to good test-retest reliability.Citation43 Past month alcohol use was logarithmically transformed for analyses to account for the positive skew.

Subclinical narcissistic traits

The Five-Factor Narcissism Inventory-Short Form FFNI-SF;Citation44 is a 60-item measure comprising 15 personality traits that was used to measure the prevalence and severity of subclinical grandiose (e.g., I am extremely ambitious and I only associate myself with people of my caliber) and vulnerable (e.g., I feel ashamed when people judge me) narcissistic traits in participants. Response options included a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (disagree strongly) to 5 (agree strongly). Subclinical grandiose traits were measured based on the sum of 44 items (α = .89) measuring indifference, exhibitionism, authoritativeness, grandiose fantasies, manipulativeness, exploitativeness, lack of empathy, arrogance, acclaim seeking, and thrill-seeking. Subclinical vulnerable traits were measured based on the sum of 16 items (α = .82) measuring reactive anger, shame, need for admiration, and distrust. Higher scores indicated stronger subclinical traits. The FFNI-SF has demonstrated good convergent validity in studies that include undergraduate students,Citation44 aligning with the notion that narcissism is viewed through a dimensional lens.Citation45

Drinking motives

The 20-item Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised DMQ-R;Citation27 was used to measure reasons for participant alcohol use. This measure was broken into four subscales with 5 items: (a) social (e.g., To celebrate a special occasion with friends?; α = .87, (b) coping (e.g., To cheer up when you are in a bad mood; α = .88), (c) enhancement (e.g., Because it makes social gathering more fun; α = .89), and (d) conformity (e.g., You drink to fit in with a group you like?; α = .88. Response options ranged from 1 (almost/never) to 5 (almost always/always) to indicate the reasons for their alcohol use. A mean score was calculated for each scale with greater scores indicating greater endorsement of that motive. The DMQ-R factor structure has been validated in previous literature across the college student population and the scale has demonstrated acceptable internal reliability.Citation46,Citation47

Analytic strategy

First, descriptive statistics were used to examine univariate distributions and bivariate associations. Next, linear structural equation modeling was used to examine the direct effects of grandiose and vulnerable narcissist traits on past month alcohol use and the potential mediating role of drinking motives in these relations. Full information maximum likelihood was used to address missing data. To assess mediation, the -medsem- package in Stata was used which follows Zhao and colleaguesCitation48 approach for testing mediation.

Results

Univariate descriptive statistics and bivariate associations are displayed in . Generally, positive correlations were observed among the drinking motives and between alcohol use and drinking motives. Grandiose and vulnerable traits were correlated but only grandiose traits were positively correlated with alcohol use. Finally, grandiose traits were positively correlated with all motives except conformity and vulnerable motives were positively correlated with all motives except social.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations among study variables.

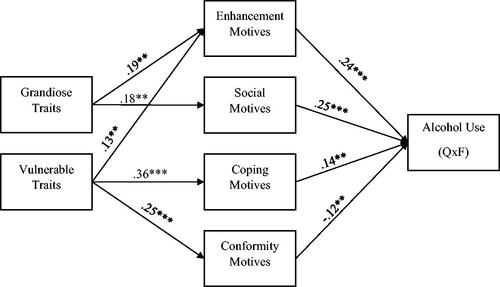

Results from a path analysis using linear structural equation models are displayed in and . The direct effects of grandiose and vulnerable motives were not significantly associated with alcohol use. However, grandiose traits were positively associated with enhancement and social motives, whereas vulnerable traits were positively associated with enhancement, coping, conformity motives. Enhancement, social, and coping motives were positively, whereas conformity motives were negatively associated with alcohol use. Examination of the effects indicated that the association between grandiose traits and alcohol use was fully mediated by enhancement (b = .003, SE = .001, p = .005) and social motives (b = .003, SE = .001, p = .006). Similarly, the association between vulnerable traits and alcohol use was fully mediated by enhancement (b = .004, SE = .002, p = .025), coping (b = .005, SE = .002, p = .044), and social motives (b = −0.044, SE = .002, p = .023).

Figure 1. Structural model for association among study variables. Only statistically significant pathways are displayed. Standardized pathways displayed. Measurement errors have been omitted for clarity. *p < . 01; **p < . 001; ***p < . 001.

Table 2. Coefficients for direct and indirect paths among study variables.

Discussion

Results from the current study suggest that drinking motives mediated the associations between grandiose and vulnerable narcissist traits and college students’ alcohol use. Unsurprisingly, since subclinical narcissistic traits are characterized by a sense of self-importance, perceived entitlement or superiority, and a need for admiration, both enhancement and social motives for grandiose traits and enhancement motives for vulnerable traits mediated associations with alcohol use. In other words, like past research,Citation41 these internal positive motives to enhance an experience or external positive motives to obtain social rewardsCitation27 may help explain why both individuals who are self-focused would engage in more alcohol use.

Coping and conformity motives also mediated vulnerable narcissistic traits albeit in different ways. Greater vulnerable traits were associated with greater coping motives which, in turn, was associated with greater alcohol use. Narcissistic vulnerability often relates to feelings of inadequacyCitation49 and neurotic behavioral traits.Citation50 Students who drink to cope also are more likely to display neurotic personality traits, such as emotional instability,Citation38,Citation51 which is significantly associated with vulnerable narcissism.Citation52 This may explain why those with vulnerable traits were more driven to consume alcohol by this internal negative motivation. Although vulnerable traits were associated with greater conformity motives, conformity motives were associated with less alcohol use. A notable trait of vulnerable narcissism is a fragile self-concept, contingent upon validation from peers.Citation53 Perhaps students with these traits were more concerned about the negative outcomes resulting from criticism or fear of embarrassment related to alcohol use. This consideration may also help explain why vulnerable traits were not associated with social motives. Perhaps individuals’ fragile self-concept and the underlying feelings of inadequacy make the external positive social motives less tangible for those with vulnerable traits. Alternatively, perhaps other contextual variables in the drinking environment (e.g., availability, drinking norms, perceived enforcement, etc.Citation54) were stronger drivers of students’ behaviors. Future research would benefit from exploring these alternative drivers of alcohol use in the context of one’s personality in the future.

Drinking to conform did not mediate the relation between grandiose traits and alcohol use. This relation is peculiar because individuals with low self-esteem are more likely to conform to social norms, particularly female college studentsCitation55 compared to students with inflated levels of self-esteem, a common trait of grandiose narcissism.Citation56 However, this relation may be partially explained by narcissistic-tolerance theory, which argues that individuals are more tolerant and accepting of others who report similar degrees of narcissistic traits and are similar in their level of these traits to that of their friends.Citation57 It is possible that students with a high degree of subclinical grandiose traits may be motivated to drink in a similar fashion to friends, given that students who recognize that their friends drink are more willing to drink themselves.Citation58

Drinking to cope also did not mediate the effect of subclinical grandiose traits on alcohol use. It may be that drinking to cope aligns more with those with vulnerable than grandiose traits given links with emotional instability.Citation38,Citation51 Further, students with high degrees of subclinical grandiose traits may be less likely to drink to cope since grandiose narcissism is negatively associated with guilt and shame, which are primary components of negative emotionality.Citation59

Limitations and future directions

Although this study provides important insights into the ways cognitive-motivational factors contribute to links between narcissistic personality traits and alcohol use among college students, we note several limitations and areas of future research. First, given this study relied on a cross-sectional design, causal inferences cannot be made. Longitudinal examinations of the links between subclinical narcissistic traits, drinking motives, and alcohol use or of how these traits and behaviors change and covary over time with drinking motives are needed. This is particularly important given young adulthood is often the age of onset for substance use disorders,Citation60 young people are actively exploring their identities and social roles,Citation24 and this period includes shifts in legal drinking status. Additionally, future studies should explore additional mediating or moderating factors that may play a role in the observed associations. For example, perceived stress severity and social relationshipsCitation61,Citation62 are factors which not only may invite drinking to cope or conform but also may uniquely interact with narcissism traits to impact drinking.

Second, students may have responded to self-report survey items with a social desirability or neutral bias. Although data were scrutinized for quality (e.g., quickly completed surveys were removed from analyses), additional considerations are warranted. Although quantity-frequency questionnaires are commonly used self-report methods to assess alcohol consumption,Citation63 future studies may benefit from exploring alternative options such as the Handheld Assisted Network Diary (HAND) or the online Timeline Follow-back (TLFB). Both instruments have shown acceptable reliability and validity when used with college studentsCitation64,Citation65 recording comparable levels of alcohol intake.Citation66 Using either the HAND or the TLFB in conjunction with a drink visual to standardize resultsCitation67 and including an additional quantity and frequency measures within a longitudinal study could prove useful.

Third, although the current study sample was not unexpected given sampling from a predominately white institution and predominantly female major, due to the sample consisting primarily of white females, findings may not generalize to other populations. Additional research is needed to replicate the current study findings with male and gender diverse and racially and ethnically diverse college student samples. This will be particularly important given the narrowing but known differences in alcohol use behaviors across gendersCitation7 and some evidence of drinking motive differences across genders and racial-ethnic groups.Citation68,Citation69 Further, as college campuses become increasingly racially and-ethnically diverse, a closer examination of intersections between how narcissistic traits, which are concerned with the self, are experienced by marginalized groups or those who seek belonging and are linked to drinking motives and alcohol use is needed. These unique experiences may have important implications for drinking motives, highlighting the need for future research.

Fourth, although students are more likely to exhibit narcissistic traits at a subclinical level, future research would benefit by employing a diagnostic interview to identify the extent of narcissism pathology across campuses. This may provide additional important insights into the ways narcissism is linked with alcohol use via cognitive-motivational factors. Lastly, this study did not account for the distinct sub-motives which encompass drinking to cope (coping-anxiety and coping-depression motives), or social tension reduction.Citation70 Future studies would benefit by using a modified DMQ-RCitation71 or Young Adult Alcohol Motives ScaleCitation70 to further investigate the significance of this distinction.

Conclusions and implications

Extending past research to investigate both grandiose and vulnerable traits and a range of drinking motives, we found that drinking motives mediate the relations between these traits and alcohol use among college students. Specifically, findings suggest that subclinical narcissistic traits may be a risk factor for diverse drinking motives and therefore alcohol use, given motives are linked with use in this population. Findings may inform efforts to reduce the harm associated with alcohol use among college students by identifying individuals particularly at risk for greater engagement. Such efforts can include campus-wide engagement and awareness programs addressing what factors contribute to particular drinking motives, motivation and motivation-related therapeutic approaches to better align student health behaviors with values relevant to their self-concept, and behavioral interventions administered by campus mental health counselors to better manage alcohol intake upon under external and internal influences. Further, findings may inform intervention efforts by campus counseling centers to foster help-seeking behaviors, especially among students who exhibit narcissistic personality traits, given evidence of the impact of these traits on treatment engagement and outcomes.Citation72,Citation73 Finally, these findings may inform prevention efforts for those with narcissistic traits or disorders and this study highlights the unique roles different drinking motives play in alcohol use behavior for those with grandiose and vulnerable traits.

Conflict of interest disclosure

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report. The authors confirm that the research presented in this article met the ethical guidelines, including adherence to the legal requirements, of the United States of America and received approval from the Illinois State University Institutional Review Board.

References

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH) releases. Available at: https://www.samhsa.gov/data/release/2022-national-survey-drug-use-and-health-nsduh-releases#annual-national-report. 2022. Accessed May 1, 2024.

- Lorant V, Nicaise P, Soto VE, d’Hoore W. Alcohol drinking among college students: college responsibility for personal troubles. BMC Public Health. 2013;13(1):615. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-13-615.

- McCabe SE, Veliz P, Schulenberg JE. How collegiate fraternity and sorority involvement relates to substance use during young adulthood and substance use disorders in early midlife: A national longitudinal study. J Adolesc Health. 2018;62(3S):S35–S43. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.09.029.

- Patrick ME, Terry-McElrath YM. High-intensity drinking by underage young adults in the United States. Addiction. 2017;112(1):82–93. doi:10.1111/add.13556.

- Hingson R, Wenxing Z, Smyth D, Zha W. Magnitude and trends in heavy episodic drinking, alcohol-impaired driving, and alcohol-related mortality and overdose hospitalizations among emerging adults of college ages 18-24 in the United States, 1998-2014. J Stud Alcohol & Drugs. 2017;78(4):540–548. doi:10.15288/jsad.2017.78.540.

- Arria A, Caldeira K, O’Grady K, et al. Drug Exposure opportunities and use patterns among college students: Results of a longitudinal prospective cohort study. Subst Abus. 2008;29(4):19–38. doi:10.1080/08897070802418451.

- White AM. Gender differences in the epidemiology of alcohol use in the United States. Alcohol Res. 2020;40(2):01. doi:10.35946/arcr.v40.2.01.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. 2013. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Aslinger EN, Manuck SB, Pilkonis PA, Simms LJ, Wright AGC. Narcissist or narcissistic? Evaluation of the latent structure of narcissistic personality disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2018;127(5):496–502. doi:10.1037/abn0000363.

- Krizan Z, Herlache AD. The narcissism spectrum model: A synthetic view of narcissistic personality. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2018;22(1):3–31. doi:10.1177/1088868316685018.

- Mitra P, Fluyau D. Narcissistic Personality Disorder. StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2023.

- Köck P, Walter M. Personality disorder and substance use disorder—An update. Mental Health and Prevention. 2018;12:82–89. doi:10.1016/j.mhp.2018.10.003.

- Alcorn JL, III, Gowin JL, Green CE, Swann AC, Moeller FG, Lane SD. Aggression, impulsivity, and psychopathic traits in combined antisocial personality disorder and substance use disorder. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25(3):229–232. doi:10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12030060.

- Fisher S, Hsu W-W, Adams Z, Arsenault C, Milich R. The effect of impulsivity and drinking motives on alcohol outcomes in college students: a 3-year longitudinal analysis. J Am Coll Health. 2022;70(6):1624–1633. doi:10.1080/07448481.2020.1817033.

- James LM, Taylor J. Impulsivity and negative emotionality associated with substance use problems and Cluster B personality in college students. Addict Behav. 2007;32(4):714–727. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.06.012.

- You DS, Rassu FS, Meagher MW. Emotion regulation strategies moderate the impact of negative affect induction on alcohol craving in college drinkers: an experimental paradigm. J Am Coll Health. 2023;71(5):1538–1546. doi:10.1080/07448481.2021.1942884.

- Dingfelder SF. Reflecting on narcissism: Are young people more self-obsessed than ever before?. Monitor on Psychology. 2011;42(2):64.

- Twenge JM, Konrath S, Foster JD, Keith Campbell W, Bushman BJ. Egos inflating over time: A cross-temporal meta-analysis of the narcissistic personality inventory. J Pers. 2008;76(4):875–902. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2008.00507.x.

- Crawford E, Moore CF, Ahl VE. The roles of risk perception and borderline and antisocial personality characteristics in college alcohol use and abuse. J Applied Social Pyschol. 2004;34(7):1371–1394. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.2004.tb02011.x.

- Hill EM. The role of narcissism in health-risk and health-protective behaviors. J Health Psychol. 2016;21(9):2021–2032. doi:10.1177/1359105315569858.

- Luhtanen RK, Crocker J. Alcohol use in college students: Effects of level of self-esteem, narcissism, and contingencies of self-worth. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(1):99–103. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.19.1.99.

- Kramer MP, Wilborn DD, Spencer CC, Stevenson BL, Dvorak RD. Protective behavioral strategies moderate the association between narcissistic traits and alcohol pathology in college student drinkers. Subst Use Misuse. 2019;54(5):863–867. doi:10.1080/10826084.2018.1547909.

- Welker LE, Simons RM, Simons JS. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: Associations with alcohol use, alcohol problems and problem recognition. J Am Coll Health. 2019;67(3):226–234. doi:10.1080/07448481.2018.1470092.

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469.

- Di Pierro R, Fanti E. Self-concept in narcissism: Profile comparisons of narcissistic manifestations on facets of the self. Clin Neuropsychiatry. 2021;18(4):211–222.

- Chung JM, Robins RW, Trzesniewski KH, Noftle EE, Roberts BW, Widaman KF. Continuity and change in self-esteem during emerging adulthood. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2014;106(3):469–483. doi:10.1037/a0035135.

- Cooper ML. Motivations for alcohol use among adolescents: Development and validation of a four-factor model. Psychological Assessment. 1994;6(2):117–128. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117.

- Roos CR, Pearson MR, Brown DB. Drinking motives mediate the negative associations between mindfulness facets and alcohol outcomes among college students. Psychol Addict Behav. 2015;29(1):176–183. doi:10.1037/a0038529.

- Choi J, Park D-J, Noh G-Y. Exploration of the independent and joint influences of social norms and drinking motives on Korean college students’ alcohol consumption. J Health Commun. 2016;21(6):678–687. doi:10.1080/10810730.2016.1153762.

- Nehlin C, Öster C. Measuring drinking motives in undergraduates: An exploration of the Drinking Motives Questionnaire-Revised in Swedish students. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2019;14(1):49. : doi:10.1186/s13011-019-0239-9.

- Skalisky J, Wielgus MD, Aldrich JT, Mezulis AH. Motives for and impairment associated with alcohol and marijuana use among college students. Addict Behav. 2019;88:137–143. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.028.

- Wahesh E, Lewis TF, Wyrick DL, Ackerman TA. Perceived norms, outcome expectancies, and collegiate drinking: Examining the mediating role of drinking motives. J Addict Offender Couns. 2015;36(2):81–100. doi:10.1002/jaoc.12005.

- Aurora P, Klanecky AK. Drinking motives mediate emotion regulation difficulties and problem drinking in college students. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2016;42(3):341–350.

- Wemm SE, Ernestus SM, Glanton Holzhauer C, Vaysman R, Wulfert E, Israel AC. Internalizing risk factors for college students’ alcohol use: A combined person- and variable-centered approach. Subst Use Misuse. 2018;53(4):629–640. doi:10.1080/10826084.2017.1355385.

- Read JP, Wood MD, Kahler CW, Maddock JE, Palfai TP. Examining the role of drinking motives in college student alcohol use and problems. Psychol Addict Behav. 2003;17(1):13–23. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.17.1.13.

- Cook MA, Newins AR, Dvorak RD, Stevenson BL. What about this time? Within- and between-person associations between drinking motives and alcohol outcomes. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2020;28(5):567–575. doi:10.1037/pha0000332.

- Cooper ML, Agocha VB, Sheldon MS. A motivational perspective on risky behaviors: the role of personality and affect regulatory processes. J Pers. 2000;68(6):1059–1088. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00126.

- Stewart SH, Loughlin HL, Rhyno E. Internal drinking motives mediate personality domain—drinking relations in young adults. Personality Individual Differ. 2001;30(2):271–286. doi:10.1016/S0191-8869(00)00044-1.

- Trull TJ, Waudby CJ, Sher KJ. Alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders and personality disorder symptoms. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2004;12(1):65–75. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.12.1.65.

- Tragesser SL, Sher KJ, Trull TJ, Park A. Personality disorder symptoms, drinking motives, and alcohol use and consequences: Cross-sectional and prospective mediation. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2007;15(3):282–292. doi:10.1037/1064-1297.15.3.282.

- Tragesser SL, Trull TJ, Sher KJ, Park A. Drinking motives as mediators in the relation between personality disorder symptoms and alcohol use disorder. J Pers Disord. 2008;22(5):525–537. doi:10.1521/pedi.2008.22.5.525.

- Finan LJ, Schulz J, Gordon MS, Ohannessian CM. Parental problem drinking and adolescent externalizing behaviors: The mediating role of family functioning. J Adolesc. 2015;43(1):100–110. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.05.001.

- Spirito A, Bromberg JR, Casper TC, et al. Reliability and validity of a two-question alcohol screen in the pediatric emergency department. Pediatrics 2016;138(6):1–10. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-0691.

- Sherman ED, Miller JD, Few LR, et al. Development of a hort form of the five-factor narcissism inventory: the FFNI-SF. Psychol Assess. 2015;27(3):1110–1116. doi:10.1037/pas000010010.1037/pas0000100.supp.

- Trull TJ, Widiger TA. Dimensional models of personality: the five-factor model and the DSM-5. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15(2):135–146. doi:10.31887/DCNS.2013.15.2/ttrull.

- MacLean MG, Lecci L. A comparison of models of drinking motives in a university sample. Psychol Addic Behav. 2000;14(1):83–87. doi:10.1037/0893-164X.14.1.83.

- Martens MP, Rocha TL, Martin JL, Serrao HF. Drinking motives and college students: further examination of a four-factor model. J Couns Psychol. 2008;55(2):289–295. doi:10.1037/0022-0167.55.2.289.

- Zhao X, Lynch JG, Jr, Chen Q. Reconsidering Baron and Kenny: myths and truths about mediation analysis. J Consum Res. 2010;37(2):197–206. doi:10.1086/651257.

- Pincus AL, Roche MJ. Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability. In: Campbell WK, Miller JD, eds. The Handbook of Narcissism and Narcissistic Personality Disorder: Theoretical Approaches, Empirical Findings, and Treatments. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; 2011:31–40.

- Miller JD, Hoffman BJ, Gaughan ET, Gentile B, Maples J, Keith Campbell W. Grandiose and vulnerable narcissism: a nomological network analysis. J Pers. 2011;79(5):1013–1042. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00711.x.

- Simons JS, Gaher RM, Oliver MNI, Bush JA, Palmer MA. An experience sampling study of associations between affect and alcohol use and problems among college students. J Stud Alcohol. 2005;66(4):459–469. doi:10.15288/jsa.2005.66.459.

- Dickinson KA, Pincus AL. Interpersonal analysis of grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. J Pers Disord. 2003;17(3):188–207. doi:10.1521/pedi.17.3.188.22146.

- Mahadevan N, Jordan C. Desperately seeking status: How desires for, and perceived attainment of, status and inclusion relate to grandiose and vulnerable narcissism. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2022;48(5):704–717. doi:10.1177/01461672211021189.

- Finan LJ, Lipperman-Kreda S. Changes in drinking contexts over the night course: Concurrent and lagged associations with adolescents’ nightly alcohol use. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2020;44(12):2611–2617. doi:10.1111/acer.14486.

- Schick MR, Nalven T, Spillane NS. Drinking to fit in: The effects of drinking motives and self-esteem on alcohol use among female college students. Subst Use Misuse. 2022;57(1):76–85. doi:10.1080/10826084.2021.1990334.

- Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: Sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, ed. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Vol 32. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000:1–62.

- Maaß U, Lämmle L, Bensch D, Ziegler M. Narcissists of a feather flock together: Narcissism and the similarity of friends. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2016;42(3):366–384. doi:10.1177/0146167216629114.

- Litt D, Stock M, Lewis M. Drinking to fit in: examining the need to belong as a moderator of perceptions of best friends’ alcohol use and related risk cognitions among college students. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2012;34(4):313–321. doi:10.1080/01973533.2012.693357.

- Czarna AZ, Zajenkowski M, Dufner M. How does it feel to be a narcissist? Narcissism and emotions. In: Hermann AB T, Foster J. eds. Handbook of Trait Narcissism: Key Advances, Research Methods, and Controversies. Springer; 2018:255–263 (eBook).

- Kessler RC. The epidemiology of dual diagnosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56(10):730–737. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.06.034.

- Courtney JB, West AB, Russell MA, Almeida DM, Conroy DE. College students’ day-to-day maladaptive drinking responses to stress severity and stressor-related guilt and anger. Ann Behav Med. 2024;58(2):131–143. doi:10.1093/abm/kaad065.

- Goon S, Slotnick M, Leung CW. Associations between subjective social status and health behaviors among college students. J Nutr Educ Behav. 2024;56(3):184–192. doi:10.1016/j.jneb.2023.12.005.

- Stevens JE, Shireman E, Steinley D, Piasecki TM, Vinson D, Sher KJ. Item responses in quantity–frequency questionnaires: implications for data generalizability. Assessment 2020;27(5):1029–1044. doi:10.1177/1073191119858398.

- Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, et al. Alcohol assessment using wireless handheld computers: a pilot study. Addict Behav. 2007;32(12):3065–3070. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.04.012.

- Pedersen ER, Grow J, Duncan S, Neighbors C, Larimer ME. Concurrent validity of an online version of the Timeline Followback assessment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2012;26(3):672–677. doi:10.1037/a0027945.

- Bernhardt JM, Usdan S, Mays D, Martin R, Cremeens J, Arriola KJ. Alcohol assessment among college students using wireless mobile technology. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2009;70(5):771–775. doi:10.15288/jsad.2009.70.771.

- Marini C, Northover NS, Gold ND, et al. A systematic approach to standardizing drinking outcomes from timeline followback data. Subst Abuse. 2023;17:11782218231157558. doi:10.1177/11782218231157558.

- Straka BC, Gaither SE, Acheson SK, Swartzwelder HS. Mixed’ drinking motivations: A comparison of majority, multiracial, and minority college students. Social Psychol Personality Sci. 2020;11(5):676–687. doi:10.1177/1948550619883294.

- Temmen CD, Crockett LJ. Relations of stress and drinking motives to young adult alcohol misuse: variations by gender. J Youth Adolesc. 2020;49(4):907–920. doi:10.1007/s10964-019-01144-6.

- King SE, Skrzynski CJ, Bachrach RL, Wright AGC, Creswell KG. A reexamination of drinking motives in young adults: the development and initial validation of the young adult alcohol motives scale. Assessment. 2023;30(8):2398–2416. doi:10.1177/10731911221146515.

- Grant VV, Stewart SH, O’Connor RM, Blackwell E, Conrod PJ. Psychometric evaluation of the five-factor Modified Drinking Motives Questionnaire–Revised in undergraduates. Addict Behav. 2007;32(11):2611–2632. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2007.07.004.

- Pincus AL, Cain NM, Wright AGC. Narcissistic grandiosity and narcissistic vulnerability in psychotherapy. Personal Disord. 2014;5(4):439–443. doi:10.1037/per0000031.

- Ellison WD, Levy KN, Cain NM, Ansell EB, Pincus AL. The impact of pathological narcissism on psychotherapy utilization, initial symptom severity, and early-treatment symptom change: A naturalistic investigation. J Pers Assess. 2013;95(3):291–300. doi:10.1080/00223891.2012.742904.