Abstract

Suicide is a global public health challenge. We explore the benefits and challenges of operationalizing strategic objectives of national suicide prevention policies locally. To implement policy effectively, local resources must be mobilized, and we investigate a real-time surveillance, principles-based model led by the police through a multiple case-study design. We found current data collected on deaths by suicide is limited and more localized responses are necessary. Multi-agency communication, utilization of existing local support systems, and emotional support for frontline practitioners is essential. Police are on the frontline for suicide and are uniquely placed to collect data and support families.

Suicide is defined as an action directly or indirectly resulting in a “self-inflicted death,” and globally, every 40 seconds a person dies by suicide (Ilgün et al., Citation2020). For each death, estimates show 20 more attempted suicide (World Health Organization (WHO), Citation2014). Despite being preventable, suicide represents a serious public health problem and in 2013 the World Health Organization (WHO) proposed their Mental Health Action Plan (2013–2020) positioning suicide prevention as a priority (WHO, Citation2014). In 2015 the United Nations General Assembly adopted Sustainable Development Goals, with suicide prevention being a core indicator, to benefit societal wellbeing and the economy (WHO, Citation2018). In response, public health officials in England took a strategic approach to prioritizing suicide prevention through their national policy. This policy highlights several strategic objectives, including, targeting high-risk groups; promoting positive mental health in vulnerable groups; reducing access to means; improving support for those bereaved by suicide; and, supporting research, data collection and monitoring (HM Government, Citation2019).

For policies to be effective, they must be translated and implemented at local levels (Butler & Allen, Citation2008). Such translation is not linear, but iteratively transformed through multiple distributed agencies communicating with each other and via their organizational processes, meaning policy content is reshaped through the incorporation of knowledge from practice (Sausman et al., Citation2016). Suicide prevention strategies must be multisectoral, and tailored to local cultural and social contexts, with clear objectives, targets, indicators, responsibilities, and budget allocations (WHO, Citation2018). Indeed, Public Health England (PHE) produced an online suicide prevention atlas of suicide data for each Local Authority to support implementation (Simms & Scowcroft, Citation2018), recognizing the need to balance national data with community-specific data (WHO, Citation2014).

Different agencies involved are required to take a coordinated interdisciplinary approach and have methods of implementation that work locally. Across these multiple agencies there are professionals who encounter people at risk of or who die by suicide. Frontline responders like the police and fire service are often called to mental health emergencies, including suicidal crises (WHO, Citation2009). The police, then are a particularly important group of professionals. If a person has experienced a “sudden death” the police investigate if the death was self-inflicted or if there is another route of investigation before turning responsibility to the coroner (Leicestershire Police, Citation2017). In these cases, it is usually the police who identify next of kin and communicate with families and other agencies. In a suicidal crisis, the police can address suicide prevention directly, through action at an attempt scene or indirectly, by working in crisis situations with individuals who have high risk factors for suicidality (Sher, Citation2016).

Given the centrality of the role, it is crucial police officers are appropriately trained to identify risks of suicide and understand mental health legislation (WHO, Citation2009). Despite first responder responsibilities, police officers are rarely provided with specialist training in suicide. Evidence demonstrates, however, training in suicide prevention is usually well received as it helps build confidence and knowledge (Marzano et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, training can increase awareness and recognition of impacts to their own mental health and personal emotional responses to suicide (Marzano et al.). Training in suicide prevention and awareness is therefore essential, as police work is a stressful occupation characterized by unpredictable events and exposure to others’ trauma, and there are high levels of depression, alcoholism and suicidal ideation and behavior amongst officers (Violanti et al., Citation2011). Problematically, however, police culture and stigma may mean there is resistance to help-seeking (Violanti, Citation2018).

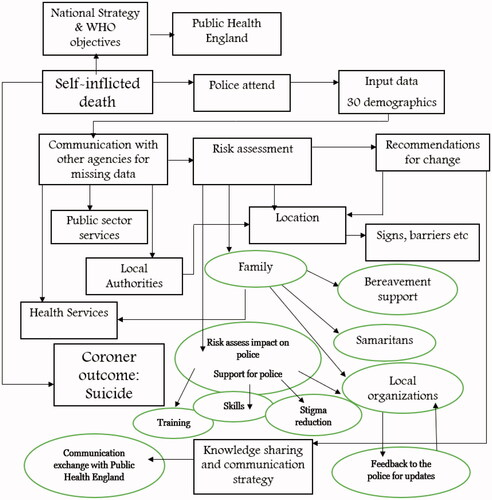

Ultimately, suicide is preventable, and the police are instrumental in understanding local issues, enacting local responses, and collating local data. Modern local responses now advocate real-time surveillance data collection, which can enhance and promote a synthesis of understanding suicidality, crisis management and bereavement support to ensure a coordinated approach to suicide prevention, intervention and postvention. Such joined-up thinking for action was postulated and campaigned for by organizations with harm reduction at the center of their ideology (Harmless, Citation2020). PHE now advocates using local intelligence for joined up thinking and action, recommending using real-time-surveillance data as the foundation (PHE, Citation2020). In other words, a real-time surveillance model is a system that enables an agency to consider and agree if interventions are needed, promote crisis management and support bereaved people; coroners or the police can lead such interventions (PHE, Citation2020). In this paper, we report a model based on real-time surveillance collection of data, for suicide prevention, intervention and postvention. This model was developed through case study research that accounts for how the police force can operationalize systemic principles through a flow-process to ensure provision of the core strategic directives of the PHE suicide prevention plan. The foundational principles of the model are translatable for any local domain for key stakeholders to interpret and transform for use in practice and seeks to meet the requirements of national policy in practice.

The model was iteratively co-created by engaging local inter-disciplinary knowledge and expertise from the police, mental health services, local authorities, charities, and academics, utilizing policy directives, evidence from research literature, and local information and expertise. Such a dialectical pluralist approach to thinking and action (see Johnson, Citation2017) promotes mixing of epistemics, integration of experience, and acknowledgement of wider political ideology. To account for these different elements and the importance of local knowledge, we call this the LOSST LIFFE Model (Learning from Officers’ Suicide Support Tasks: Leicester Investigation of a Framework for Family Engagement).

Method

We utilized a case study design to develop and iteratively shape the model. The development of this model was co-produced, led by BT and engaging the academic team led by MO. We involved a range of additional agencies including the National Health Service (NHS), charity sector (especially Harmless and Leicester Samaritans), and other frontline professionals.

For qualitative research, case study work is one major tradition (Cresswell, Citation1998) and often located within the interpretative paradigm. Case study designs are valuable for research problems that are complex, intersecting, and/or poorly understood. These allow researchers to investigate the business of organizations as well as their interconnections with communities and agencies (Yin, Citation2003). There are different types of case study designs, with different foci and goals. We utilized the instrumental case study approach, whereby each case provides insight into the specific issue to build the theory/model, and the case is selected in relation to existing knowledge (Stake, Citation2005).

We thus, took a multiple-case study approach. Multiple-case study designs enable researchers to explore core issues at stake across cases to transfer the findings to build theory (Yin, Citation2003). Such designs are committed to studying the complexity of real-world situations in depth, accounting for varied perspectives related to it (Simons, Citation2009) and benefitting from prior expert knowledge (Yin, Citation2003).

Data collection

The model reported was created via three stages. First, through engagement with research evidence, PHE directives, and local police knowledge and experience, we created the initial template by identifying important steps in suicide prevention and the types of data that may be needed to address the problem. This early view recognized the value and importance of collating data on self-inflicted deaths at the point of the event, and in a way that extended traditional data collection approaches and allowed us to create a basic process of action that might be implemented in practice. Thus, data collection was our starting point, with the creation of demographic details via a spreadsheet.

Second, we undertook consultative dialogue with different agencies, including PHE, social care, education, mental health, local authorities, and local/national charities, which created opportunities to develop the model through an interdisciplinary lens. The engagement with representatives from different organizations was led by the police, specifically the suicide prevention lead (BT) who through this role consulted, liaised with, and facilitated the implementation of a range of local resources. The police lead documented outcomes of that engagement through reflective practice and key issues identified through consultation informed our developmental work alongside continued attention to the academic literature. In creating the process of flow for the model, we consulted the new strategic plan (HM Government, Citation2019), we mapped its primary objectives against our initial inception of the model, and we made refinements to ensure it was fit for purpose. At this point in the process, we collated many real-world cases of deaths by suicide and we gave our model further modifications using the case study approach. These cases form the data collection reported here.

At the point of writing there were 415 deaths by suicide since the model’s initial inception and each death represents a single case of suicide informing development. As we noted, we gradually built our model, and our case study design is exploratory and qualitative. This means that the final model presented here was informed by the cases, the literature, and the expertise of those involved. To manage the data and decide case selection we attended to the pragmatic issues and the within case-characteristics, focusing predominantly on typicality to promote representativeness (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008). We thematically organized the issues highlighted by the suicide cases and based on typicality, present the three most relevant conceptual categories, with illustrative examples to the development of the model.

Third, to identify gaps and recognize barriers to implementation, we interviewed 15 police officers to improve process, recognize resource challenges, and find strategic ways to meet the objectives in the national plan at local levels (these data are not reported here in this paper).

Ethics

Ethical approval was granted by the University of Leicester ethics committee. We additionally followed all due process through the internal police approval procedure for data sharing. The police released the secondary data (demographic spreadsheets), suicide notes, and case study material. In this paper, we report details of the case study aspect and focus on how the model was developed.

Results

We identified three case studies that contributed to the iterative building of the model. These cases are selected from a wide range of available examples and thus those that are used here simply highlight the development process of the model.

Case study one: locally generated knowledge

A core thematic conceptual category highlighted in the very early stages was that there was insufficient data collected on persons who died by suicide at a national level. The early inception of the model, therefore, relied on officers inputting data on 30 demographics of individuals who died through self-inflicted death on a pre-determined spreadsheet. The inclusion of these different demographics being systematically recorded oriented to the identified challenge of the need for data. The concept of self-inflicted death is utilized to circumnavigate lengthy delays in the conclusion of suicide, especially as most eventually result in that outcome. Some demographics recorded were known at the scene or easily obtained shortly thereafter, others required active information-seeking. The Office for National Statistics (ONS) typically collects demographics of age, gender, area, occupation and method of death, and our LOSST LIFFE model adds 25 information points. This includes information about the person’s personal life (e.g. if they had children, were married, residential address), their health history (physical, mental), whether anyone witnessed the event and details about the death (location, method). Additional protected characteristics are recorded, like disability, ethnicity, religion, and sexual orientation.

In current police practices there is insufficient access to current data around suicide and this limited knowledge makes it challenging for agencies to respond to and prevent further suicides in a timely manner. The type of data gathering at local level proposed by our LOSST LIFFE model is important, as data provided by the ONS takes time to be released and is limited in scope. Thus, the demographic recording part of the LOSST LIFFE process creates a real-time surveillance data corpus as advocated by PHE (Citation2020), providing a foundation for response that facilitates mobilizing action by the police and local agencies when needed for crisis management, intervention and postvention.

Case study two: location, location, location

The national suicide prevention strategy recognizes the importance of factors like access to means and location (HM Government, Citation2019). Evidence shows approximately one third of deaths by suicide occur in a public location (Owens et al., Citation2009), typically buildings, bridges, or sections of roads and railways (Owens et al., Citation2019). Preventative action relies on agencies, like the police and local authorities, identifying areas of risk (Owens et al., Citation2015). Evidence suggests that restricting means, such as installing barriers and erecting signs is effective (Pirkis et al., Citation2013) as they disturb the suicidal plan by prompting a cognitive interruption (National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), Citation2019).

During the second iteration of our model development, we undertook close interrogations of issues related to the location of a self-inflicted death. We provide our case example here of a problematic carpark that for 12 months saw 3 self-inflicted deaths, 2 attempts, 28 negotiations, and 16 incidents involving other services. Because of the detailed data collection process outlined in case study one, police were able to undertake real-time surveillance of the location and implement locally relevant practical strategies to reduce risk of further death.

The detail in data collection allowed expertise from the local Suicide Audit and Prevention Group to address different areas of support. First, local authorities provided signage around car park entrances (particularly pedestrian entrances) to offer support. Second, the police provided suicide awareness training to carpark staff. This course transcended assisting staff to recognize suicidal behavior by encompassing active resilience and networking opportunities to ensure a pathway for emotional support if they were impacted by a death. Finally, the police addressed the challenge of barriers into the carpark to ensure the purchase of a ticket was necessary to enter. The implementation of barriers was difficult due to the cost without recompense to the carpark company. As part of the LOSST LIFFE initiative through the built-in communication strategy with the Local Authority, the police lead consulted with planning committees for the county through an open dialogic process to account for future risk in planning permission for new car parks.

Case study three: communication and support

The national prevention plan identifies the need for police officers to engage in multi-agency communication and the relevance of seeking additional information about the deceased person (HM Government, Citation2019). HM Government argue it is necessary to provide bereavement support through local partnerships between local authorities, NHS organizations and the voluntary/charitable sector. During the second iterative phase of development, by co-working with other agencies, we were able to implement ideas locally. We achieved this implementation through a county and city-wide partnership pathway to support and inform families and communities after a self-inflicted death. This kind of extended local support framework is crucial. Indeed, the NICE (Citation2019) clarified the necessity of tailored support for those who are bereaved due to suicide because of their increased likelihood of suicidal ideation and suicidal behavior.

As an example, officers attended the sudden death of a man who had returned to live with his mother following an accumulation of debt. Two weeks after his death, police revisited the mother to offer bereavement support. The mother was overwhelmed with grief, guilt, and responsibility. Cumulative responsibilities were burdensome, including communication with her son’s landlord who declined to return the deceased person’s personal property, instead retaining it in lieu of debt for rent owed, and managing the mobile phone company who required a death certificate to terminate the contract. The mother had limited personal support due to separation from her son’s father. Through the implementation of the model, police identified a package of localized support systems associated with the model resources, including Citizens Advice, the Samaritans, and The Tomorrow Project. Consequently, by engaging in supportive communication with these locally enacted systems, the mother could find tailored bereavement support for parents experiencing loss. The actions of officers engaging with the mother helped those officers to reflect and strengthen practice, and by consulting other agencies locally the mother received support. It is the case that following a self-inflicted death, bereaved persons will need to be signposted to sources of support and the police can do this. Indeed, although having multiple areas of support could generate confusion, the systematic processes associated with the multidimensional aspects of the LOSST LIFFE model allowed those who are bereaved to make a choice about who they approach for support, empowering them in the creation of their own bereavement pathway.

The outcome: the model

The LOSST LIFFE model is a systemic community-focused operational approach to responding to and preventing suicide. The implementation of this model provides a mechanism for acquiring high levels of demographic detail, methods of interrogating core issues pertinent to incidents, and communication strategies for involving other local agencies at a community and public service level. This model has at its center a systemic ecology recognizing the triad of persons; the deceased person, the family/close network of peers, and the wider public who may be subject to similar risk factors (e.g. location). The model accounts for socio-political systems, organizational systems, local community systems and family systems. The unique value of this model is the focus on real-time surveillance, proactive processes, and localized relevance. In doing so, it utilizes existing resources, tailoring them to suit local situations. It achieves its local focus by operationalizing national strategic objectives in a practical and meaningful way, by providing a set of principles for an action-based method for local social and cultural need. The model is therefore founded on a philosophy of knowledge exchange and implementation, multi-agency dialogue and systemic thinking.

As indicated, the model underwent different iterations. During our third phase, the primary goal was identifying gaps and barriers for implementation. To identify gaps, barriers to implementation, and strategies to inform those practice-based changes, we undertook interviews with police officers. We also added additional demographics to the spreadsheet, taking the total to 33, and include: later died in hospital, former veteran, and recently released from prison. Primary gaps in the model actions during this phase recognized the need for more tailored and proactive family bereavement support as illuminated with case study three. Further gaps recognized the cumulative impact on the police officers themselves, bidirectional feedback between local agencies and the police (rather than unidirectional), and a broader communication strategy for information sharing, especially with PHE. Furthermore, we also implemented a pathway for sharing information allowing other agencies such as the NHS and British Transport Police to share relevant and related data. The process of flow of the model is visually represented in .

Discussion

Suicide is a serious global problem, and countries need practical methods for implementing national suicide prevention plans. England, specifically, took positive steps, with an appointment of a Minister for Patient Safety, Suicide Prevention and Mental Health to oversee policies. Suicide rates have reduced, but statistics suggest they are rising again (see Gayle, Citation2019), and certain groups are especially vulnerable to risk factors associated with suicide. In a recent review, there were a range of factors associated with suicide attempts and suicide capability (Klonsky et al., Citation2017). Risk factors include physical or mental illness, stress, alcohol and substance use, family issues, and economic challenges (Piotrowski & Hartmann, Citation2019), with the most substantive risk being mental health conditions (Randall et al., Citation2014) and these are multidimensional and overlapping (Piotrowski & Hartmann, Citation2019).

The police are one professional group playing a critical role in attending to individuals in crisis, attending scenes of self-inflicted death, and engaging in multi-agency communication to act on suicide response and prevention. Through our case study research, we developed and implemented a model of practice underpinned by national strategic objectives, local organizational knowledge and expertise, and accounts for a wider interdisciplinary research evidence base. The purpose of this model is to outline a set of translatable principles and processes that police forces across England specifically, and other countries generally, can adopt and adapt to suit their own local regions. By taking a systemic approach, the police can tailor existing resources, work effectively with other organizations to create a local environment that is responsive to and takes a proactive position on suicide prevention.

Our case study design was processual and iterative, and the model has currently been subject to three phases of development and real-world implementation in practice. As such it provides a practice-based evidence approach underpinned by a dialectical pluralist philosophy (Johnson, Citation2017). A dialectical pluralist approach is interdisciplinary, values local practitioner knowledge and experience, and hears the voices of relevant stakeholders. This model has shown great promise in providing a mechanism for real-time surveillance and provides an established basis to assist officers in their data recording and decision-making processes when attending a self-inflicted death. It is wholly necessary to adopt the principles of LOSST LIFFE to achieve national objectives, because local, cultural, and specific community factors need to be addressed and to achieve this relies on local resources in terms of economic, time, expertise, and skills of professionals.

Early evaluation indicates the model is showing signs of success in key domains. For example, there has been a reduction in those bereaved by suicide dying by suicide in Leicestershire, which suggests the bereavement offer added in phase three is having some impact. As part of the bereavement offer, police officers attending any self-inflicted death provide bereaved families with written information that contained local rather than general or national sources of support. Furthermore, the value of the data has provided a tool for developing important initiatives, such as the “start a conversation campaign” across organizations. Although it may seem that empathy and humanity in suicide prevention are central to any endeavor, it is typically overlooked, and yet the implementation of LOSST LIFEE meant officers had a mechanism to respond rapidly to human need. It can be challenging for police officers as they are not working at a population level but are responding to individual events. Police officer responses are particularly evident in the active engagement with local partner agencies (e.g. Leicester Samaritans, Harmless, and GP Practices) to offer support to those bereaved. Academic studies have continued to show people bereaved by suicide are at further risk of suicide (Van Orden et al., Citation2010). We managed to implement LOSST LIFFE into local practice and by using the data generated were able to ensure the commissioning of local programs to support bereaved people as well as giving them a platform to be heard. The LOSST LIFFE model advocates the use of existing resources in doing so, and most forces in England will be associated with Suicide Prevention Groups led by Public Health. For successful crisis management, prevention, and postvention, it is necessary officers take time to attend, collect data, share experiences, and monitor the bereavement support package. The bereavement support aspect is especially important in cases where bereaved relatives resist the conclusion of suicide, or where there are sensitive religious or cultural challenges.

Those working in suicide should never be complacent, whether working in practice or research, and the LOSST LIFFE model is flexible and adaptable to suit changing local situations and evolving guidelines. Future directions require the implementation of the model on a wider scale across England and these discussions are currently in place. As the model becomes more widely adopted, there will be future opportunities for a larger-scale evaluation of the processes. In particular, with greater uptake we will be able to look in more depth how the model is translated to suit different local regions, how this implementation can contribute to the wider national objectives, and the extent to which this implementation might benefit the national communication strategy across agencies.

Although the work reported in this paper is ostensibly limited, as it is based on one large region of England and one police force, it nonetheless represents a wide range of expertise and voices from different professional backgrounds as the model has evolved through natural practices. Furthermore, we note that the region of England (Leicestershire) has a large and ethnically diverse population. The makeup of this population means that there is some representativeness of our findings. Such representation is beneficial, given evidence that the most vulnerable and disadvantaged sectors of society are most affected by suicide (Sun & Zhang, Citation2016), and the model represents and responds to these groups accordingly.

In conclusion, the model in its conception was to provide police and local partners with access to data to improve suicide prevention, intervention and postvention work and understand the risk factors related to suicide in a more efficient manner. Through early implementation, the novel aspect was in its simple innovation in accounting for the value of a humane response, which has not been fully realized despite its central necessity in practice. Leicestershire Police at the beginning of the model development was 179 years old and had no doubt, been attending sudden death (including suspected suicides) for those 179 years. The simplicity and transparency of creating a demographic profile associated with self-inflicted deaths brought to the fore a need to recognize bereaved loved ones, who, often in shock, typically felt overpowering sense of guilt and responsibility. By having an integration of detailed data across a broad spectrum of relevant matters, local support systems, and engagement across agencies, local organizations (including the police) the model allows the identification of new issues arising and a strong platform of response. This moves beyond typical constraints of national suicide prevention and response plans, where police wait for final coroner conclusions and slow the production of knowledge. It is the case that the data collection process means that the local police force can now understand and address suicide and suicide prevention on a scale not possible in other English regions, as the use of the model relies on more than just real-time surveillance data collection to achieve the goals of suicide prevention and includes a coordinated action-focused approach to the multiple domains of suicide work. It is clear, that to tackle suicide, we need a more immediate, flexible, and locally tailored response, which the LOSST LIFFE model promotes.

Acknowledgment

Barney Thorne would like to acknowledge the assistance, support and care afforded to him by former suicide prevention lead, Luke Russell and Fred Swaffield, who built the database and system Leicestershire Police use.

References

- Butler, M., & Allen, P. (2008). Understanding policy implementation processes as self-organizing systems. Public Management Review, 10(3), 421–440. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14719030802002923

- Cresswell, J. (1998). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five traditions. Sage.

- Gayle, D. (2019). Suicide rates in UK increase to highest level since 2002. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2019/sep/03/suicides-rate-in-uk-increase-to-highest-level-since-2002

- Harmless. (2020). Resource hub. https://harmless.org.uk/resource-hub/.

- HM Government. (2019). Cross-government suicide prevention workplan. HM Government.

- Ilgün, G., Yetim, B., Demirci, S., & Konca, M. (2020). Individual and socio-demographic determinants of suicide: An examination of WHO countries. International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 66(2), 124–128. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764019888951

- Johnson, R. (2017). Dialectical pluralism: a metaparadigm whose time has come. Journal of Mixed Methods Research, 11(2), 156–173. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1558689815607692

- Leicestershire Police. (2017). Investigation of deaths policy. https://www.leics.police.uk/SysSiteAssets/foi-media/leicestershire/policies/investigation_of_deaths_policy_po19.0_sept_17.pdf.

- Klonsky, E., Qiu, T., & Saffer, B. (2017). Recent advances in differentiating suicide attempters from suicide ideators. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 30(1), 15–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0000000000000294

- Marzano, L., Smith, M., Long, M., Kisby, C., & Hawton, K. (2016). Police and suicide prevention: Evaluation of a training program. Crisis, 37(3), 194–204. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000381

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2019). Suicide prevention: Quality standard. NICE.

- Owens, C., Derges, J., & Abraham, C. (2019). Intervening to prevent a suicide in a public place: A qualitative study of effective interventions by lay people. BMJ Open, 9(11), e-032319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-032319

- Owens, C., Hardwick, R., Charles, N., & Watkinson, G. (2015). Preventing suicides in public places: A practice resource. Public Health England.

- Owens, C., Lloyd-Tomlins, S., Emmens, T., & Aitken, P. (2009). Suicides in public places: Findings from one English County. European Journal of Public Health, 19(6), 580–582. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckp052

- Piotrowski, N., & Hartmann, P. (2019). Magill’s medical guide. Salem Press.

- Pirkis, J., Spittal, M., Cox, G., Robinson, J., Cheung, Y., & Studdert, D. (2013). The effectiveness of structural interventions at suicide hotspots: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 42(2), 541–548. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyt021

- Public Health England. (2020). Local suicide prevention planning: A practical resource. PHE.

- Randall, J., Walld, R., Finlayson, G., Sareen, J., Martens, P., & Bolton, J. (2014). Acute risk of suicide and suicide attempts associated with recent diagnosis of mental disorders: A population-based, propensity score matched analysis. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 60(6), 245–257.

- Sausman, C., Oborn, E., & Barrett, M. (2016). Policy translation through localisation: Implementing national policy in the UK. Policy & Politics, 44(4), 563–589. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1332/030557315X14298807527143

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research: A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Sher, L. (2016). Commentary: Police and suicide prevention. Frontiers in Public Health, 4, 119. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00119

- Simms, C., & Scowcroft, E. (2018). Suicide statistics report: Latest statistics for the UK and Republic of Ireland. Samaritans.

- Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. Sage.

- Stake, R. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N Denzin & Y Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (pp: 443–466). Sage.

- Sun, B., & Zhang, J. (2016). Economic and sociological correlates of suicides: Multilevel analysis of the time series data in the United Kingdom. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 61(2), 345–351. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1556-4029.13033

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

- Violanti, J. (2018). Police officer suicide. Oxford Research Encyclopaedias.

- Violanti, J., O’Hara, A., & Tate, T. (2011). On the edge: Recent perspectives on police suicide. Charles C Thomas Publishers.

- World Health Organization. (2009). Preventing suicide: A resource for police, firefighters and other first line responders. WHO.

- World Health Organization. (2014). Preventing suicide: A global imperative. WHO.

- World Health Organization. (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: Progress, examples and indicators. WHO.

- Yin, R. (2003). Case study research: design and methods (3rd ed). Sage.