Abstract

Role confusion is a prominent constituent symptom of Prolonged Grief Disorder in parents after their infants die from sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). We interviewed 31 parents of SIDS infants 2–5 years post-loss examining the parental role before death, at the time of loss, and in bereavement. Thematic analysis found disruption of the role and re-imagined responsibilities for their child’s physical security, emotional security, and meaning. Tasks within these domains changed from concrete and apparent to representational and self-generated. Parents in bereavement locate ongoing, imperative parental responsibilities, particularly asserting their child’s meaningful place in the world and in their family.

In most cases of sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), a parent has placed their seemingly healthy infant to sleep and later discovers them dead. Children dying from SIDS are, by definition, under the age of one year. Their bereaved parents are typically less than 40 years of age, with lives centered on future plans for their young, growing families. New parents are routinely counseled about safe sleep practices during medical encounters for their child and, although more babies currently die of SIDS after being placed to sleep in the supine rather than in the prone position (Trachtenberg et al., Citation2012), the popular view of SIDS is that it is an accident that responsible parents can prevent. A death from SIDS requires a mandated medicolegal investigation and acutely bereaved parents often report that they have been treated with suspicion and accusation at the time when they are struggling with their first moments of loss (Garstang, Citation2018). SIDS is a leading cause of infant mortality in developed countries (Goldstein, Blair, et al., Citation2019).

Grief in parents after the death of a young child is frequently severe (Gamino et al., Citation1998; Middleton et al., Citation1998; Zisook & Lyons, Citation1988), with an elevated risk for Prolonged Grief Disorder (PGD) when compared to other kinship relationships (Kersting et al., Citation2011; Zetumer et al., Citation2015). The sudden unexpected death of a dependent child in early life, in particular, encompasses many risk factors associated with more difficult grief (Michon et al., Citation2003; Morris et al., Citation2019). In previous research, we found that rates of PGD among mothers whose infants died without established cause from SIDS reached 57.1 percent at one year following loss (Goldstein et al., Citation2018), in comparison to the prevalence of 9.8 percent found among bereaved life partners (Lundorff et al., Citation2017). Role confusion was the most prominent and severe of the cognitive and behavioral symptoms that contributed to PGD in these bereaved mothers, and it persisted with little decrease for at least four years post-loss.

The prevailing heuristic of grief as an attachment disorder suggests that the severity of PGD correlates with the intensity of attachment behavior (Shear & Shair, Citation2005), with heightened significance during infancy when this behavior is particularly strong. The behavioral system of dependent and vulnerable infants is oriented around the goal of attaining proximity to the parent, the function of which is protection from harm (Bowlby, Citation1969). Parental caregiving reciprocates this behavior, in part, by responding to the infant’s signals and by keeping their child close to protect them (Ainsworth, Citation1989; Solomon & George, Citation1996). Such strong parental behavior and duties are abruptly interrupted by an infant’s death. Reconciling a child’s death at any age with those duties can be difficult, and the perceived central duty as protector may contribute to a belief that they have failed their child (Fletcher, Citation2002; Oliver, Citation1999; Wing et al., Citation2001). Self-blame, guilt, and shame are commonly experienced among bereaved parents (Duncan & Cacciatore, Citation2015; Ostfeld et al., Citation1993), with 40–50 percent of parents of infants reporting self-blame during the acute period of loss and notable persistence relative to other symptoms associated with bereavement (Duncan & Cacciatore, Citation2015).

The inability to “make sense” of the loss has been found to be the most salient predictor of grief severity (Keesee, Citation2010). While meaning making involves more than a concrete explanation for the cause of death, this finding is especially relevant in SIDS, a diagnosis of exclusion applied only when no explanation can be found. Further, many of the typical ways of constructing meaning after life-altering events, such as drawing lessons from the way their child lived (Lichtenthal & Breitbart, Citation2015; Wheeler, Citation2001), are unavailable to parents who lose an infant to SIDS. Unlike many populations in which meaning making has been studied (Denhup, Citation2017; Meert et al., Citation2015; Nuss, Citation2014), parents whose children die of SIDS uniquely face questions about accountability and frequently face accusations from law enforcement, the medical field, friends or family (Crandall et al., Citation2017; Garstang, Citation2018). The suddenness of their child’s death and their child’s young age may heighten the challenge of reconciling the death with their expectations about a just or fair world (Dyregrov et al., Citation2003; Park, Citation2010; Wijngaards-De Meij et al., Citation2008).

Research exploring ways in which parents reimagine the parental role when faced with the death of their child has focused on parents whose children died of cancer or life-limiting illnesses (Clancy & Lord, Citation2018; Meert et al., Citation2015; Nuss, Citation2014). These studies found that parents adapt their definition of what it means to be a “good parent” (Hinds et al., Citation2009) at the end of their child’s life through a process that emphasizes several tasks, including “making sure their child feels loved,” “focusing on their child’s health,” and “making informed decisions” (Feudtner et al., Citation2015; Hill et al., Citation2019). For parents whose children die from SIDS, this process of adaptation is not possible prior to death due to its sudden and unexpected nature, affecting the “reorganization” (Bowlby & Parkes, Citation1970) of incorporating loss into a new identity or way of being (Bretherton, Citation1992).

In this qualitative study, we analyzed semi-structured interviews of bereaved parents whose infants had died from SIDS to explore how the parental role toward their infant continues in bereavement. We investigated how parents who lose an infant to SIDS define what it means to be a good parent to their child, and how they view their duty toward their child after their death.

Materials and methods

Sample

Participants were parents of deceased infants enrolled in Robert’s Program in Sudden Unexpected Death in Pediatrics at Boston Children’s Hospital. Fifty-three English-speaking parents from 31 families whose infants (under 1 year of age) had died suddenly and unexpectedly in the prior two to five years were identified as potential participants. We chose the two-year minimal post-loss interval because our previous research found that the association between PGD and the presence of particular pre-loss risk factors (depression, trait anxiety, previous losses, death of only child) or their accumulated number, diminished in significance after two years (Goldstein, Petty, et al., Citation2019). Participants were invited to participate by letter sent by mail and/or email. Participants provided informed consent and were offered a $25 gift card as compensation. This study was approved by The Institutional Review Board of Boston Children’s Hospital.

Procedures

We conducted semi-structured interviews investigating the parental role, parents’ experiences, and their priorities. Interviews were conducted individually with each parent, except for three couples who requested to be interviewed jointly. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, all but one of the interviews were conducted via video teleconference. Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Field notes on the interview, as well as the interviewers’ initial reactions, were documented immediately following each interview. The interviews asked participants to reflect on their parental role and parenting priorities prior to their child’s death, how aspects of their parental role changed in the acute period immediately following their child’s death, and their parental role in bereavement. The interviews included articulation of what the participants understood a “good parent” to be relative to the death of their infant. Demographic data about the participants and their infants were collected.

Data analysis

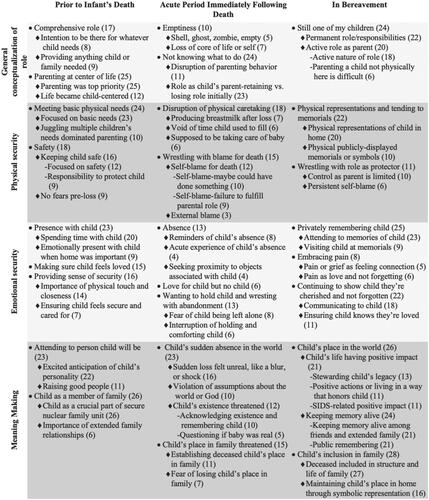

We conducted thematic analysis to identify and interpret themes expressed in the interviews using a multistage, inductive approach. Interview transcripts were uploaded to NVIVO (v.12) qualitative research software program (QSR International Propriety Limited, 2019). The transcripts were manually coded into specific descriptive nodes and grouped into clusters, which were reviewed and revised by EJP and RDG during coding meetings after independent determinations, to ensure the trustworthiness of the data. The most significant nodes (by frequency) in each time period relative to loss were identified and organized into four domains, as shown on the left side of . Nodes in each time period were compared for commonalities and differences to determine emergent themes, which were then revised through iterative review of the data. Exemplary data extracts were selected, and the analytical narrative was developed.

Figure 1. Analytic clusters into which individual nodes were grouped are displayed here. Circular bullet points indicate major clusters of nodes, diamond bullet points beneath indicate nodes within that cluster, and dashed bullet points indicate sub-nodes. The number of interviews in which the node was referenced, out of 28 total interviews, are included in parentheses.

Results

Thirty-one parents (58% mothers; 11% couples), representing 18 families from 10 US states and one province in Canada agreed to be interviewed (58% response rate). Of the 53 individuals invited to participate by letter, 9 declined to participate, 9 were unreachable for follow-up by email or phone, and 4 initially expressed interest but subsequently did not respond to communication. Their infants’ ages at the time of their deaths ranged from 11 days to 10 months, and the mean age of their infants at death was 4 months. Approximately two-thirds of parents had older children, and 84 percent had given birth to subsequent children since their child’s death. The infants of two couples were twins. The demographic information for parents and their children can be found in .

Table 1. Parent demographic information (n = 31).

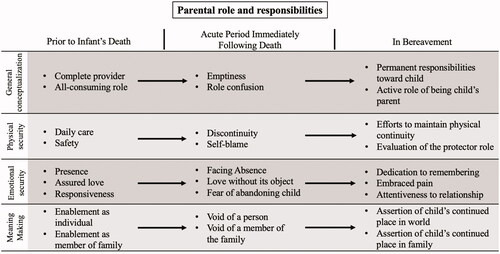

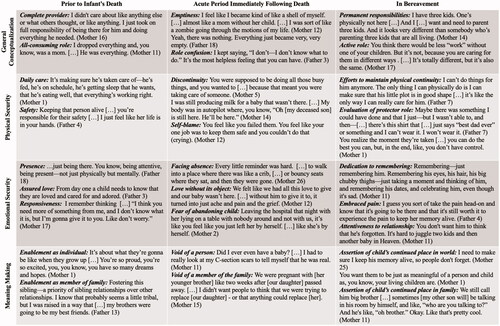

Our analysis followed the time references of the interview cues: prior to the infant’s death, the acute period immediately following the infant’s death, and in bereavement. We identified three main domains when analyzing the parental role across time: physical security, emotional security, and meaning making, with distinct themes in each. The domains and themes are presented in and representative quotations are presented in . The features of each theme are presented below by time period and domain, corresponding with the structure in which they are displayed in .

Figure 2. Themes from the analysis of clustered nodes (in ) are displayed as bullet points within the domains listed vertically on the left side of the figure. Arrows indicate shifts in themes over time.

Figure 3. Representative quotations for each theme. Each grayscale row marks a different domain, and each column marks the time period relative to the child’s death. The arrangement of the quotations mirrors the display of the themes in .

Prior to the infant’s death

The general conceptualization of the parental role was that it is a complete and all-consuming role. Parents described various ways in which they viewed themselves as a complete provider for their child’s needs when their infant was alive. Many reflected on their commitment to “do anything” for their child and to “be there” for whatever they needed. Parents spoke of providing any material needs for their child and making sure “everything was going to be ok” (Father 7). Parents embraced an expansive role of being “responsible for another human being” (Father 4) and some explained that their life’s purpose centered on satisfying the role of being a parent. They spoke of sacrificing personal interests in service of an unquestioned priority.

Domain 1: Physical security

Meeting their child’s basic needs was among the top three parenting tasks across all domains prior to loss. Parents provided for and responded to their infant through practical tasks of feeding, maintaining sleep schedules, and changing diapers. Some parents articulated a sense of responsibility for their child’s health and well-being, while others spoke of “just making sure we got through the day” (Mother 2). When infants slept poorly or had difficulty gaining weight, parents felt a personal responsibility that they failed to meet the responsibilities of their role.

Safety was a focus for a majority of parents prior to loss. They described following safe sleep guidelines, checking on their child in the middle of the night, and feeling responsible for keeping their dependent child alive. Some indicated that their most fundamental responsibility was protecting the life of their child. At the same time, in about a third of the interviews, the parents commented on their illusion of invulnerability, i.e., that they lived without fear that their child might die or in naiveté about the possibility that their child could die. Many operated under the assumption that if they “followed the rules,” their child’s life was not at risk.

Domain 2: Emotional security

Among the three most prominent themes of the overall parental role prior to loss was the importance of being present as they raised their child. “Just being there” (Mother 23), both physically and emotionally, was a highly prioritized aspect of their parental role. Parents spoke of scaling back on work in order to be home and emphasized the importance of being emotionally and cognitively attentive to their child when they were with them.

Many parents also emphasized cultivating a loving environment for their child as one of their most important priorities. The centrality of providing assured love was repeatedly emphasized in interviews. Similarly, providing the child with a sense of security through ready responsiveness to their emotional needs or distress was identified. Many spoke of the importance of holding their child or comforting them with physical touch and closeness, ensuring they felt protected and “cared for.”

Domain 3: Meaning making

Over three-quarters of parents described their anticipation for their child’s future and the unique person they would become. They did not express a duty to create these qualities but instead spoke as custodians for their child while their innate qualities emerged. Approximately a third of parents did, however, emphasize their anticipated responsibility to raise their child to be a “good person” and their intentions to instill values of compassion, generosity, or humility.

Nearly all parents commented on the importance of helping their child become who they were within the context of their family, as a sibling and member of a larger family. Parents expressed hopes that their infant and his or her siblings would grow up to support and protect each other, develop close bonds, or balance each other’s personalities. For many, the joy and fulfillment of seeing these bonds begin to form and evolve contributed to a sense that the infant made their family feel complete. This sense of completeness was expressed by over half of the participants, including first-time parents or parents who were considering having more children.

Acute period immediately following the child’s death

The general conceptualization of the parental role was emptiness and role confusion. About a quarter of participants, both mothers and fathers, spoke of emptiness or being hollowed out after their child died. Some described feeling like a “ghost” or a “shell” of themselves. In a majority of interviews, parents articulated a sense of uncertainty about their role as a parent in the period immediately following their child’s death. A quarter of parents recalled feeling lost or not knowing what to do from moment to moment when their child died. Many emphasized that they continued to see themselves as their deceased child’s parent but were unsure how to fulfill that role. Two recalled wondering if they were still their child’s parent.

Domain 1: Physical security

The sudden interruption of tending to their child’s daily care and sustenance was frequently noted and described in terms of disorientation and yearning to physically care for their child. One father recalled: “I would just be up [in the middle of the night] because I wish that that’s what I was doing” (Father 7). The discontinuity and yearning had a physical component for breastfeeding mothers, whose engorgement or need to pump served as distressing reminders of their tragic interruption. Mothers also described the loss of holding and comforting their child as one that they experienced physically, recounting the sensation of their arms aching or feeling empty. Another recalled still being able to feel her child in her hands.

The death of their infant undermined their assumptions and beliefs as parents that they could and would protect their child. Confronted with this discrepancy, parents blamed themselves for their child’s death, a theme that emerged as among the most commonly emphasized aspects of acute loss. Interestingly, self-blame was not associated with having put their child to sleep in the higher-risk prone position. Some parents expressed guilt for not having somehow prevented their child’s death, or a sense that they must have missed something. For others, the experience of self-blame was accompanied by a sense that they had failed to fulfill a fundamental parental role to protect their child. Only a few parents spoke of external blame from police or medical examiners. Participants did not report experiences of accusation from family members or others in their social circles. Instead, most identified internal sources of blame.

Domain 2: Emotional security

The physical absence of the child dominated the acute loss period. Much that parents encountered in the first months—for example, an empty crib and being around other mothers or babies—were sharp reminders of their child’s absence. Some sought proximity to objects associated with their child, recognizing and accepting the pain that accompanied it.

Some parents recalled not knowing how or where to direct the love they felt for their child and confessed to the need to figure out what to do with that love. This desire to find a way to continue loving was a prominent aspect of acute loss. Without their child to hold and comfort, parents experienced the loss of providing a sense of security to their child, confronting the challenge of not abandoning their child despite their physical absence. A few spoke of being pained by the thought that their infants were alone when they died while others emphasized a feeling of abandonment on leaving the body of their child after death.

Domain 3: Meaning making

Anger and disbelief at their child’s sudden death and absence in the world were dominant features of the acute period following the child’s death. Over a third of parents emphasized experiencing their child’s death as globally and profoundly unjust. They recalled being unable to believe that an apparently healthy child could die; emphasizing that a parent is “not supposed to bury [their] kid” (Mother 2). Many parents expressed ways in which the substantiality of their child’s life felt threatened and spoke of the importance of others acknowledging that their child was here in the world. Some recalled questioning whether their baby was ever real.

The threat to their child’s meaning in the context of their family was also a prominent feature of parents’ experience of acute loss. In a quarter of interviews, parents expressed fear that their child’s place in the family would get lost, a fear that seemed to be amplified for those who became pregnant soon after their child died. They felt responsible for determining how to protect their child’s place and role in their family.

In bereavement

The general conceptualization of the parental role was permanent and active responsibilities. Parents spoke of a continued relationship as a parent to their deceased infant, with ongoing responsibilities in their parental role. They noted both the challenge of parenting a child who had died and an increasing understanding of what that role might entail. An ongoing intention to actively carry out the responsibilities of being a parent to their deceased child, particularly those of assuring their child’s place in the world and family, was almost universally expressed. Doing so required diligent attention to this role, and some emphasized that they were constantly learning and seeking new ways to do this.

Domain 1: Physical security

After their child’s death, the parental role of physically sustaining their infant shifted to assuring the child’s continued physical presence by maintaining, and sometimes tending to, symbolic representations of the child. About one-third of parents expressed the importance of physical memorials honoring their child in public places, such as grave sites, statues, benches or trees, or publicly displaying symbols of their child, including wearing jewelry or tattoos representing their child. Physical representations of, or memorials to, their child within their homes were even more commonly emphasized.

There were two sub-themes in parents’ reflections on their parental role to protect their child: persistent self-blame and a revised understanding of whether they ever actually had the power as a parent to keep their child safe. At the time of their interviews, some parents continued to blame themselves for their child’s death, but similar numbers questioned whether it was ever within their control to guarantee their child’s safety. The implications of this tension could be seen in changed attitudes in the care of their other or subsequent children. The complex and often paradoxical implications they noted included anxiety and rigidity about safety alongside a focus on cherishing the present and being more flexible in their parenting.

Domain 2: Emotional security

Many parents spoke of maintaining an emotional presence with their child by setting aside time to reminisce about them, regularly taking quiet moments to remember their child or privately visiting their child’s memorial site; doing so was a part of being their child’s parent. The pain they experienced with this was typically embraced as a manifestation of the continued love they felt for their child. One father put it succinctly, “Pain is love and love is pain.” Others explained that the pain was worth experiencing because it meant they were remembering their child.

Parents described regularly talking or writing to their child as a means of providing assurance to the child that they continued to be cherished. Over half of parents communicated to their child in some way, and some stated they felt guilty if they did not do so frequently or diligently enough. For a few, the communication often included apologizing to their child or telling them that they were missed. Others updated their child on what was happening in their lives or the lives of their families, sometimes asking their child to help them. Parents viewed their communication to their child as a manifestation and cultivation of their ongoing relationship with them.

Domain 3: Meaning making

The responsibility to “keep their child’s memory alive” in the thoughts of other people was the second most-prominent theme of the parental role in bereavement. Parents spoke of daily efforts to maintain their child’s presence in the world, including talking about their child though others avoided it and posting blog entries or photos on social media. Some found it reassuring and important to hear other people talk about their child or say their name, which they experienced as others recognizing their child’s existence and value. Many spoke of the challenges of responding to the question, how many children do you have? or other questions about their family, wanting to acknowledge their deceased child yet admitting to its emotional toll. Parents also identified difficulties in stewarding the memory of a child who died so young because their child had not yet fully developed their personality or formed many relationships outside of their immediate family.

Many parents stated that they acted as a good parent to their child through their actions in the community. These activities included hosting public events or fundraisers to raise awareness and support SIDS research, donating funds to build play areas that families could enjoy together, or supporting other parents who had similarly lost their child. A few parents explained that simply being a kind person or the best version of themselves was an important way of honoring their child’s life and how their child shaped them.

The importance of meaningfully including their child in family life was expressed in every interview. Some parents explained that the family was the most critical realm in which they needed to ensure that their child was honored and had a permanent place. Nearly all parents explained that their deceased child continued to be a sibling to their other children. They celebrated their deceased child’s birthday as a family and talked about them with their living children, including younger children. At the same time, over half of parents emphasized the loss of the sibling relationships for which they had hoped and the unique ways they anticipated their child would shape the dynamics and personalities within the family.

Some parents also noted their responsibility to assert their child as a member of their extended family. They sought ways to continually re-imagine and assert their child’s place and role in the family as grandchild, cousin, and niece or nephew. They appreciated when their extended family talked about their deceased child and reinforced their child’s meaning within the family.

Discussion

We found profound disruption in the responsibilities and meaning participants once believed encompassed good parenting after their infants died from SIDS. Their role as parents changed from one that was concrete and apparent to one that was self-generated and representational, as they continued to operate under an imperative to be their child’s parent in a world where their child was no longer present (Schut et al., Citation2006). Their core responsibilities were tested within three domains of parenting: physical security, emotional security, and meaning making. Threatened by discontinuity and role confusion in each of these domains, parents reconstituted their role with new commitments and responsibilities, notably the creation of meaning by cultivating their child’s legacy and protecting their “existence” in the world and their family. Meaning making went from being an assumed aspect of daily activity to becoming the greatest part of the parent role, as that role shifted from socially validated to personal.

The participants described lives that once displayed the attachment and reciprocal caregiving behavior that characterizes the parent-infant relationship. Their days were centered around their infants’ physical and emotional needs, providing daily care and sustenance as well assuring presence, love, and responsiveness. Parents were immersed in a time of promise and reverent anticipation of who their child would become and how their child would change their family, confident in the significance of both their child and their parental activities. Being the parent to an infant was transformative for both the parent and family unit (Fadjukoff et al., Citation2016).

Our findings provide granularity to the role confusion that has been noted to be a prominent feature of this time for bereaved parents (Goldstein et al., Citation2018). Their child’s unexpected death caused a sudden cessation or discontinuation of their ability to provide physical and emotional security and challenged both the meaning of parenthood and their beliefs about what being a good parent entailed. Parents described profoundly disorienting, often visceral, experiences of the interrupted physical and emotional circuits of caretaking. Mothers, in particular, reported physical manifestations of this discontinuity. The sustenance, love, and responsiveness that they had previously directed to their child were suddenly left without their object or reciprocation. Parents felt that they had failed at their most essential duty as a parent: to ensure their child’s safety and survival. Their role as a parent to the deceased infant became less and less apparent to others as time went on.

A large discrepancy ensued between what they intended to provide as a parent and their inability to keep their child safe, leading to confusion, emptiness and self-blame. “Parental vulnerability,” helplessness due to the inability to protect one’s child from harm that propels the parent to “re-defining parenthood” (Nuss, Citation2014), was noted to be especially acute among participants. Importantly, the sense of control and parental self-efficacy described in parents caring for their children through terminal illness (Sullivan et al., Citation2020) were unavailable to them.

Many parents experienced the death of their child as a violation of the basic order of the universe and the meaning of their parenthood. They felt betrayed and abandoned by God or the world, echoing the shattering of their “assumptive world” (Lichtenthal & Breitbart, Citation2015; Parkes, Citation1971, Citation1976; Price & Jones, Citation2015; Wheeler, Citation2001), and parents in this study experienced emptiness and apprehension about the erasure of their child in the world and in their family (Wheeler, Citation2001).

The parental role in bereavement centered on actions that affirmed their child’s existence, resisting the void left by their child’s absence by finding ways to assert the core duties they performed when their child was alive. They reconstructed ways of providing physical and emotional security to their child by devoting time for being present to their child’s memories, maintaining physical memorials, embracing the pain of loss as an act of love, and by privately talking or writing to them.

Their commitment to protect and advocate for their child’s importance in the world was predominant, and parents conveyed the effort required to assert it. By taking on new responsibilities to nurture their child’s memory and legacy as core aspects of their parental role in bereavement, they addressed multiple meaning-related challenges (Lichtenthal & Breitbart, Citation2015) to reestablish their identity as a parent. They worked to preserve the sense that their child’s life had meaning, many expressing reverence for their child’s influence on them as a person and parent, and this was especially clear in the importance they placed on maintaining their child’s place in the nuclear family. This affirmation required adaptation as the living family grew and changed without the deceased child and as younger siblings grew to be older than the deceased child. Their deceased child was a part of the life and structure of their family—the middle child, or the big sibling to a younger child not yet born when they died.

Parents also described the effects of their infant’s death on how they were a parent to their other children, suggesting an intergenerational transmission of this profound family event. The loss became part of their family’s history and values. Supporting their living children’s developing understanding of death and grief, their relationship with their deceased sibling, and their capacity for resilience became new parenting priorities. Greater emphasis on cherishing the present and being flexible in their parenting coexisted alongside heightened anxiety about safety and a restricted sense of self-efficacy in their ability to protect their child from harm. This intergenerational transmission of loss merits further exploration and quantitative analysis in future studies.

The generalizability of this research is limited by sample size and possible selection bias. Due to convenience sampling from an established cohort, the demographics of the sample are not representative of the racial composition of SIDS deaths and are biased to over-represent parents with sufficient resources to access our program. One aspect of the stigma of SIDS is that these deaths are socially disenfranchized, and the parental role may change differently in other kinds of deaths for which there may be greater sympathy (e.g., childhood cancer). Given the size of the cohort, we lacked power to make useful correlations about PGD and its constituent symptoms and chose not to screen for it in our cohort. Future research with larger samples sizes could further define the role of grief severity in post-loss parenting.

Bereaved parents after SIDS redefined their role to continue nurturing the presence of a deceased child and to incorporate the child’s death into the family’s character. Despite these efforts, parents continued to struggle with role confusion, experienced most fundamentally in not being able to protect their child and their significance to the world. This research generated hypotheses about the transformation of the parental role in bereavement and may have implications for clinical care of parents and their children after SIDS by increasing awareness of its longstanding consequences.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the parents who participated in this study for their generosity in sharing their stories. This work was supported by the Harvard Medical School Fellowship, funded by the Harvard Medical School Office of Scholarly Engagement, and the Jude Zayac Foundation Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential competing interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Ainsworth, M. S. (1989). Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychologist, 44(4), 709–716. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.44.4.709

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Volume I Attachment. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J., & Parkes, C. M. (1970). Separation and loss within the family. In E. J. Anthony & C. Koupernik (Eds.), The child in his family: International yearbook of child psychiatry and allied professions (pp. 197–216). Wiley.

- Bretherton, I. (1992). The origins of attachment theory: John Bowlby and Mary Ainsworth. Developmental Psychology, 28(5), 759–775. https://doi.org/10.1080/00140136508930819

- Clancy, S., & Lord, B. (2018). Making meaning after the death of a child. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 27(4), xv–xxiv. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2018.05.011

- Crandall, L. G., Reno, L., Himes, B., & Robinson, D. (2017). The diagnostic shift of SIDS to undetermined: Are there unintended consequences? Academic Forensic Pathology, 7(2), 212–220. https://doi.org/10.23907/2017.022

- Denhup, C. Y. (2017). A new state of being: The lived experience of parental bereavement. Omega, 74(3), 345–360. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815598455

- Duncan, C., & Cacciatore, J. (2015). A systematic review of the peer-reviewed literature on self-blame, guilt, and shame. Omega, 71(4), 312–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815572604

- Dyregrov, K., Nordanger, D., & Dyregrov, A. (2003). Predictors of psychosocial distress after suicide, sids and accidents. Death Studies, 27(2), 143–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180302892

- Fadjukoff, P., Pulkkinen, L., Lyyra, A. L., & Kokko, K. (2016). Parental identity and its relation to parenting and psychological functioning in middle age. Parenting, Science and Practice, 16(2), 87–107. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2016.1134989

- Feudtner, C., Walter, J. K., Faerber, J. A., Hill, D. L., Carroll, K. W., Mollen, C. J., Miller, V. A., Morrison, W. E., Munson, D., Kang, T. I., & Hinds, P. S. (2015). Good-parent beliefs of parents of seriously ill children. JAMA Pediatrics, 169(1), 39–47. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.2341

- Fletcher, P. N. (2002). Experiences in family bereavement. Family & Community Health, 25(1), 57–70. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003727-200204000-00009

- Gamino, L. A., Sewell, K. W., & Easterling, L. W. (1998). Scott & white grief study: An empirical test of predictors of intensified mourning. Death Studies, 22(4), 333–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811898201524

- Garstang, J. (2018). Parental perspectives. In J. R. Duncan & R. W. Byard (Eds.), SIDS sudden infant and early childhood death: The past, the present and the future (pp. 123–141). University of Adelaide Press.

- Goldstein, R. D., Blair, P. S., Sens, M. A., Shapiro-Mendoza, C. K., Krous, H. F., Rognum, T. O., & Moon, R. Y. (2019). Inconsistent classification of unexplained sudden deaths in infants and children hinders surveillance, prevention and research: Recommendations from The 3rd International Congress on Sudden Infant and Child Death. Forensic Science, Medicine, and Pathology, 15(4), 622–628. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12024-019-00156-9

- Goldstein, R. D., Lederman, R. I., Lichtenthal, W. G., Morris, S. E., Human, M., Elliott, A. J., Tobacco, D., Angal, J., Odendaal, H., Kinney, H. C., & Prigerson, H. G. (2018). The grief of mothers after the sudden unexpected death of their infants. Pediatrics, 141(5), e20173651. Article 20173651. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3651

- Goldstein, R. D., Petty, C. R., Morris, S. E., Human, M., Odendaal, H., Elliott, A., Tobacco, D., Angal, J., Brink, L., Kinney, H. C., & Prigerson, H. G. (2019). Pre-loss personal factors and prolonged grief disorder in bereaved mothers. Psychological Medicine, 49(14), 2370–2378. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291718003264

- Hill, D. L., Faerber, J. A., Li, Y., Miller, V. A., Carroll, K. W., Morrison, W., Hinds, P. S., & Feudtner, C. (2019). Changes over time in good-parent beliefs among parents of children with serious illness: A two-year cohort study. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 58(2), 190–197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2019.04.018

- Hinds, P. S., Oakes, L. L., Hicks, J., Powell, B., Srivastava, D. K., Spunt, S. L., Harper, J., Baker, J. N., West, N. K., & Furman, W. L. (2009). “Trying to be a good parent” as defined by interviews with parents who made phase I, terminal care, and resuscitation decisions for their children”. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 27(35), 5979–5985. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0204

- Keesee, C. N. (2010). Predictors of grief following the death of one’s child. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(10), 430–441. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp

- Kersting, A., Brähler, E., Glaesmer, H., & Wagner, B. (2011). Prevalence of complicated grief in a representative population-based sample. Journal of Affective Disorders, 131(1–3), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.032

- Lichtenthal, W. G., & Breitbart, W. (2015). The central role of meaning in adjustment to the loss of a child to cancer: Implications for the development of meaning-centered grief therapy. Current Opinion in Supportive and Palliative Care, 9(1), 46–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/SPC.0000000000000117

- Lundorff, M., Holmgren, H., Zachariae, R., Farver-Vestergaard, I., & O'Connor, M. (2017). Prevalence of prolonged grief disorder in adult bereavement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 212, 138–149. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.030

- Meert, K. L., Eggly, S., Kavanaugh, K., Berg, R. A., Wessel, D. L., Newth, C. J. L., Shanley, T. P., Harrison, R., Dalton, H., Dean, J. M., Doctor, A., Jenkins, T., & Park, C. L. (2015). Meaning making during parent-physician bereavement meetings after a child's death. Health Psychology, 34(4), 453–461. https://doi.org/10.1037/hea0000153

- Michon, B., Balkou, S., Hivon, R., & Cyr, C. (2003). Death of a child: Parental perception of grief intensity – End-of-life and bereavement care. Paediatrics & Child Health, 8(6), 363–366. https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/8.6.363

- Middleton, W., Raphael, B., Burnett, P., & Martinek, N. (1998). A longitudinal study comparing bereavement phenomena in recently bereaved spouses, adult children and parents. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 32(2), 235–241. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048679809062734

- Morris, S., Fletcher, K., & Goldstein, R. (2019). The grief of parents after the death of a young child. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 26(3), 321–338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-018-9590-7

- Nuss, S. L. (2014). Redefining parenthood: Surviving the death of a child. Cancer Nursing, 37(1), E51–E60. https://doi.org/10.1097/NCC.0b013e3182a0da1f

- Oliver, L. E. (1999). Effects of a child’s death on the marital relationship: A review. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 39(3), 197–227. https://doi.org/10.2190/1L3J-42VC-BE4H-LFVU

- Ostfeld, B. M., Ryan, T., Hiatt, M., & Hegyi, T. (1993). Maternal grief after sudden infant death syndrome. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics, 14(3), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004703-199306010-00005

- Park, C. L. (2010). Making Sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

- Parkes, C. M. (1971). Psycho-social transitions: A field for study. Social Science & Medicine, 5(2), 101–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/0037-7856(71)90091-6

- Parkes, C. M. (1976). Determinants of outcome following bereavement. OMEGA – Journal of Death and Dying, 6(4), 303–323. https://doi.org/10.2190/PR0R-GLPD-5FPB-422L

- Price, J. E., & Jones, A. M. (2015). Living through the life-altering loss of a child: A narrative review. Issues in Comprehensive Pediatric Nursing, 38(3), 222–240. https://doi.org/10.3109/01460862.2015.1045102

- Schut, H. A. W., Stroebe, M. S., Boelen, P. A., & Zijerveld, A. M. (2006). Continuing relationships with the deceased: Disentangling bonds and grief. Death Studies, 30(8), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600850666

- Shear, K., & Shair, H. (2005). Attachment, loss, and complicated grief. Developmental Psychobiology, 47(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1002/dev.20091

- Solomon, J., & George, C. (1996). Defining the caregiving system: Toward a theory of caregiving. Infant Mental Health Journal, 17(3), 183–197. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199623)17:3<183::AID-IMHJ1>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Sullivan, J. E., Gillam, L. H., & Monagle, P. T. (2020). After an end-of-life decision: Parents’ reflections on living with an end-of-life decision for their child . Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 56(7), 1060–1065. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14816

- Trachtenberg, F. L., Haas, E. A., Kinney, H. C., Stanley, C., & Krous, H. F. (2012). Risk factor changes for Sudden Infant Death Syndrome after initiation of back-to-sleep campaign. Pediatrics, 129(4), 630–638. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1419

- Wheeler, I. (2001). Parental bereavement: The crisis of meaning. Death Studies, 25(1), 51–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180126147

- Wijngaards-De Meij, L., Stroebe, M., Stroebe, W., Schut, H., Van Den Bout, J., Van Der Heijden, P. G. M., & Dijkstra, I. (2008). The impact of circumstances surrounding the death of a child on parents’ grief. Death Studies, 32(3), 237–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701881263

- Wing, D. G., Clance, P. R., Burge-Callaway, K., & Armistead, L. (2001). Understanding gender differences in bereavement following the death of an infant: Implications for treatment. Psychotherapy, 38(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-3204.38.1.60

- Zetumer, S., Young, I., Shear, M. K., Skritskaya, N., Lebowitz, B., Simon, N., Reynolds, C., Mauro, C., & Zisook, S. (2015). The impact of losing a child on the clinical presentation of complicated grief. Journal of Affective Disorders, 170, 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.08.021

- Zisook, S., & Lyons, L. (1988). Grief and relationship to the deceased. International Journal of Family Psychiatry, 9(2), 135–146.