Abstract

Altruism is consistently identified as the dominant motive for body donation. Over 12 months, 843 people who requested body donation information packs also completed research questionnaires that included open-ended questions about their motives. Abductive analysis suggested two distinct sets of altruistic motives: those seeking benefits for medical professionals and patient groups (“medical altruism”) and those seeking benefits for friends and family (“intimate altruism”). Either could facilitate or impede body donation. Altruism may not be best understood as a unitary motive invariably promoting body donation. Rather, it is a characteristic of various motives, each of which seek benefits for specific beneficiaries.

A core question within psychology and social science asks why people engage in behaviors that appear to improve others’ welfare; sometimes collectively called “helping” or “prosocial” behaviors (El Mallah, Citation2020). A complementary question asks why people act “altruistically”, i.e., in attempts to improve others’ welfare (Eisenberg & Miller, Citation1987). More specific questions ask why people try to help, and are helpful, in medical, healthcare, and health-affecting domains such as blood donation, organ donation, or clinical trial participation (Meslin et al., Citation2008).

One such domain is body donation, where people register their willingness for their body to be examined after death in service of medical education, medical training, or medical research. (Readers can find out more about body donation in the UK from https://www.hta.gov.uk/.) In many countries, all or most bodies used for such “anatomical examination” are obtained via donation (Habicht et al., Citation2018). Understanding enhancers of and impediments to body donation is important both to ensure continued ethical supply of a valuable resource and to improve understanding of altruism and the other-affecting behaviors that it can sometimes motivate (Farsides & Smith, Citation2020).

Despite people seeming to have literally hundreds of reasons for registering as body donors (McClea & Stringer, Citation2010), an impressive set of studies from around the world, using various methods, shows remarkable consistency in the sorts of motivational considerations apparently most important to potential body donors. Gürses et al. (Citation2019) make a valuable contribution to this literature and also provide a concise but thorough review of the set of studies to which they are contributing (see especially p. 372, and also Mueller et al., Citation2021). This body of work consistently suggests that the motives most important to body donors include desires to try to: be helpful or useful, show appreciation or gratitude, avoid burial, avoid particular funeral ceremonies, and avoid “waste.”

Given the broad consistency of these findings, it seems timely to examine in more detail what people mean when they report their motives for (or against) body donation. For example, while altruism or something like it is often identified as an important motive, there is arguably a lack of clarity about who people intend to benefit from body donation, and how, and why. Past research suggests that there may be important subdivisions in, and perhaps important overlap among, such motives. More precisely identifying what people seek when considering becoming body donors has the potential to ethically and practically improve recruitment and support of body donors.

Materials and methods

Ethics

Approval for the research was obtained from the Research Governance and Ethics Committee of Brighton and Sussex Medical School (ER/BSMS3867/10). Participants gave written, informed consent, including for the use of anonymized quotes in publications resulting from the research.

Design

People who requested information about and consent forms for body donation were invited to voluntarily complete and return an accompanying questionnaire with the title, “The perceptions of body donors about the act of whole-body donation and body donation practices”.

Sample

In the United Kingdom and Ireland, anatomy offices coordinate body donation activities for geographical areas that include one or more hospital or university anatomy department. Between 1 January 2018 and 1 January 2019, everyone who requested a body donation information pack from any of 4 anatomy offices were also sent an anonymous questionnaire. The four offices were at the Universities of Cardiff (Wales), Dundee (Scotland), and Trinity College Dublin (Eire), plus The London Anatomy Office, which serves eight medical schools in London and the South East of England. Eight hundred and forty-three questionnaires were returned to the participating anatomy offices, who forwarded them to the third author. Selected characteristics of this sample are shown in . Participants’ ages ranged from 19 to 107 years old (Mage = 69.57, SD = 12.47, skew = −.73, Kurtosis = 1.08). Although different numbers of participants were recruited from each site, participants from each region were similarly aged and distributed approximately equally across the genders, religious stances, and relationships represented in .

Table 1. Selected sample and sub-sample characteristics, by geographical site.

Data collection

The four-page questionnaire included demographic questions and questions relating to the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB, see https://people.umass.edu/aizen/index.html). Using standardized “1 to 7′ response scales, the TPB questions assessed such things as participants” beliefs about, attitudes toward, and intentions regarding registering as a body donor. Because this paper focuses on analysis of participants’ qualitative data, analysis of the TPB data will be reported elsewhere.

Prior to the TPB questions were three open-ended questions: “From your personal point of view, what are the main advantages of becoming a body donor?”; “From your personal point of view, what are the main disadvantages of becoming a body donor?”; and “What is (are) the main reason(s) for your current decision to become, or not to become, a body donor? Please be as specific as you can.” Open-ended questions later in the questionnaire periodically asked participants if they had “any further comments” about answers given to immediately preceding TPB questions. The questionnaire ended, “If there is anything else you would like to tell us, please use the space below”. Answers to the open-ended questions formed the qualitative data set for the study reported here. In total, this comprised over 40,000 words, i.e., an average of about 50 words per participant (ranging from 0 to over 400). Robinson (Citation2021) stresses the necessity and advantages of qualitatively analyzing such relatively brief texts.

Data analysis

In line with recommendations provided by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), and as part of a process of generating a grounded theory of motives for body donation, the first author conducted Thematic Analysis as described by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This involves recursive phases of data familiarization, data coding, theme identification, theme clarification, theme definition and naming, and report production. These phases being recursive facilitate an “abductive” analysis in line with the principles of “constant comparison” (Glaser, Citation1965). In part, this involves alternating between inductive, “bottom-up,” “data-to-theory” analysis (Gerring, Citation1999), and deductive, “top-down,” “theory-to-data” investigation of the adequacy of that analysis (Timmermans & Tavory, Citation2012). Abductive methods are considered a necessary step in scientific development because they are particularly suited to exploring the precise nature (i.e., the qualities) of phenomena under investigation (Eronen & Bringmann, Citation2021). In line with the goal of developing a grounded theory of motives for a particular behavior, analysis sought to identify both themes (i.e., factors that seemed explanatorily important for substantial portions of the sample) and relationships among those themes (e.g., sub-themes, causal relationships, etc.). The first author wrote memos throughout the analytic process to document his thoughts and decisions. Each aspect of the first author’s analysis was checked by at least one of the other authors.

To give a sense of the initial stages of this analysis, the following extract shows part of the qualitative data provided by one participant, “coded” to show labels for potential themes (indicated in brackets that follow potential content for such themes) and potential relationships among themes (with possible sub-themes indicated after colons and possible causality indicated by underlined words).

P[articipant] 412: Feels good (Benefit: Positive affect) to be able to (Possibility) contribute (Benefit: Contribution) to training of health care professionals (Benefit: Medical education) and (Multiple determinants) to leave an ongoing (Enduring) legacy (Benefit: Legacy) after my death (Death) … As I have no close relatives (Absent impediment: Intimates) and (Multiple determinants) I have no religious beliefs (Absent impediment: Religion), I see no point (Benefit: None) in having a funeral or other rites (Absent impediment: Disposal)

To give readers a sense of how themes were identified, developed, and selected for particular attention, the following is an extract from a memo devoted to such matters:

10 Feb 2021: The answer to “Why?” often seems to be “Why not?” Many participants seem to focus on (a) the absence of their need for their cadaver, and (b) the cadaver’s potential for helping medics and researchers and, via them, patients, society, etc. With this combination of considerations, registering for possible donation seems to these participants to be a no-brainer: what would need explanation would be indifference or opposition to body donation.

Results

Overview

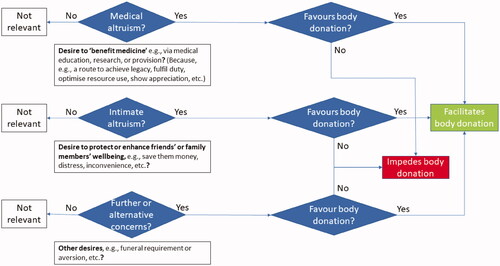

Analysis identified themes which seemed to reflect phenomena that were motivationally important to relatively large numbers of participants. As shown in , three major themes were “medical altruism,” “intimate altruism,” and “further or alternative concerns,” each of which could facilitate or impede body donation.

Various “reasons for medical altruism” were identified, including desires to express “gratitude or appreciation;” to comply with “perceived prescriptions;” to achieve “a good end”; and to “be useful”. Participants seemed to give no clear reasons for their intimate altruism. Although participants often specified how they wanted to benefit their loved ones (e.g., financially), they rarely if ever specified why they wanted to do so.

Several factors distinctive of body donation seemed particularly to facilitate medical altruism: participants having no personal use for their bodies after death (“disembodied altruism”); donation facilitating satisfaction of goals in addition to medically altruistic ones (“altruistic bonus”); and participants seeing possible benefits to medicine as decisive in the absence of identified benefits from non-donation (“waste aversion”).

The “decisions” represented in (using diamond shapes) illustrate the complexity of the relationship between altruism—of different sorts—and body donation attitudes, decisions, and behaviors. Medical altruism or intimate altruism or further concerns (diamonds on the left), if present (“yes”), can be individually sufficient to trigger the question (diamonds on the right) of whether the presence of each of these things promotes positive body donation attitudes. If they do (“yes”), that is a motivational factor pushing toward donation. If they do not (“no”), that is potentially an impediment of registering as a donor. Thus, the behavioral consequences of each motivational concern needs to be considered in terms of whether it promotes or impedes positive donation attitudes and in terms of the effects of any other co-existent motivational factors. In short, it needs to be considered in context.

Medical altruism

Reflecting past findings, the vast majority of participants expressed desires to benefit health care professionals, people or institutions that support such professionals, patient groups, or some combination of some or all of these. We labeled the most inclusive conception of such concern “medical altruism.” Collectively, participants motivated by medical altruism sought to support something like “health and health-care in society,” i.e., a diffuse and largely abstract entity, albeit one sometimes “represented” by particular individuals, e.g., specific professionals from whom participants had received medical care.

Three sub-themes of medical altruism had such frequent and consistent exemplars that data quickly became “informationally redundant” with respect to them. (Informational redundancy occurs when available information does little to affect analytic results despite strenuous consideration and a keen commitment to represent data optimally [Braun & Clarke, Citation2021].) These sub-themes identified medical altruism directed toward medical education (P2: “Genuinely feel I can help NHS to provide staff with opportunity to practice before going on the wards”; P41: “Helps medical students”), medical science (P15: “In some small way I may be helping medical science”; P19: “May help medical advances”), and medical provision (P22: “To assist medical practice;” P36: “To aid and improve health care in the future”). For convenience, we use “medicine” as a collective noun to refer to all intended beneficiaries of medical altruism.

The data left little room for doubt that most participants were motivated—at least in part and to some degree—by medical altruism. Not only did most participants indicate a goal to benefit medicine, many did so in ways that made it clear that this was a goal to which they were emphatically committed: P201: “It is my greatest wish to help in the advancement of all aspects of medicine”; P482: “If I can help the medical profession to learn about the body, I will be at peace knowing mankind will benefit”; P579: “My main reason is to help future medical persons, also help in future research.… If I can help when I die, it's a gift to me.”

Reasons for medical altruism

Participants gave several reasons for wanting to try to benefit medicine via body donation. One reason (or set of reasons) was a desire to express gratitude or appreciation: P160: “A marvelous surgeon … saved my life. I never had the opportunity to express my gratitude to him;” P378: “To recognize the medical care I and other members of my family have received over many years”; P560: “It has been invaluable to me as a student to have the possibility to observe and perform dissection … I would like to return the ‘favour’ one day by allowing future generations the same option.”

A second reason (or set of reasons) motivating some participants’ medical altruism was a desire to comply with “perceived prescriptions”: P454: “I have a number of friends who died from dementia, Alzheimer’s, motor neuron disease, cancer etc. and felt that if donating my body could help in some small way, I should”; P576: “To help research in the future. Everyone should do it. It should be compulsory”; P626: “A moral obligation.”

A third reason motivating some participants’ medical altruism was a desire to promote “a good end” to their lives, e.g., by enacting their self-perceived traits of helpfulness or by redeeming lives that they thought were lacking in such virtuous qualities: P389: “I have helped people all my life, so to donate my body is the best thing and last thing I can do”; P603: “Giving my body for research would be a fitting way to bringing my life to a close!;” P713: “I don't think that I have contributed very much to anything … in my life, really… Therefore, I feel that to donate my body would be a final selfless act”.

The fourth motive identified as commonly promoting medical altruism was the attractiveness of “being useful:” P61: “Helping to advance the knowledge of the human body.… My husband and I both decided to try to make ourselves useful after death;” P311: “Peace of mind, in anticipation that I can be of some use to assist in research and physically be a contributor to medical research/study of the human body”; P620: “Helping medical education, helping students to learn.… Feels good to think one's body will be useful to others”.

Distinctive facilitators of medical altruism in body donation

Participants often gave the impression that the presence or extent of their medical altruism was highly dependent on circumstances distinctive of and sometimes unique to body donation. Many participants, for example, suggested that their concerns and actions were substantially influenced by the belief that they would not personally experience either the event to which they were committing (i.e., body donation) or any of its consequences (e.g., anatomical examination). It seemed important to these participants that the personal costs to them of these events would be zero, i.e., because they would be dead. We called this “disembodied altruism.” While participants similarly anticipated no personal benefits at the time of or after (posthumous) donation, they often clearly enjoyed anticipating while alive the possibility that others might benefit from their actions: “Once I die, my soul/spirit leaves behind an empty vessel.… I really do not mind what any part of my body is used for. Am just happy at the thought that it can be used for good” (P22); “I don't need my body after I die, so, if I can help others, I would like to do so” (P284); “Bit of a 'feel good' factor to think of doing something useful after one's death. After all, I won't need the husk that is left!” (P783).

Some participants seemed attracted to promoting the medical benefits that donating their body might bring, but this nevertheless seemed potentially secondary to or conditional on donation also satisfying other desires. We called this an “altruistic bonus”: “My son lives [abroad] and I want to make things as easy as possible for him. I then decided that I wanted to continue to be useful after my death” (P209); “I have no one who will pay to … dispose of this vehicle my spirit has used for my lifetime. I'd rather science benefit as opposed to pauper service” (P401); “Donating my body will improve the education of health care professionals and help to advance medical science in the future. The thought of being buried or cremated fills me with dread” (P465).

The opposite of being able to “add altruism” when satisfying other goals is to be unable to satisfy altruistic desires as much as one would like, which we called “altruistic restriction”. This was most obvious when participants were motivated by medical altruism to become posthumous organ donors but felt restricted by circumstances to be able “only” to become body donors, which they found attractive but sub-optimal: P616: “I had [a specified medical condition] … and therefore can't become organ donor. I want to give something back to medicine”; P735: “As I have reached a certain age, I believe that my organs would not be of great use, so I am donating my body;” P790: “I want any suitable organs to save another life. I want the rest of my body to be used for further medical research.”

Associated with both disembodied altruism and altruistic bonus was the belief that—given the alternatives—becoming a body donor was a way to “avoid waste,” e.g., of money, of material resources, or of an opportunity to help: P257: “My body will be of some use to the medical profession. And money would not be wasted on a funeral”; P281: “Why waste a body when it can be used for medical research?;” P616: “What's the point of just being cremated or buried? It's a waste of an opportunity to be part of something greater, to be part of learning and research.”

Intimate altruism

Many participants expressed concern for the welfare of specific friends and family members, a phenomenon we labeled “intimate altruism”. This concern seemed to be for the welfare of particular individuals (e.g., “my wife”) rather than for an entire social category and all its members (e.g., “my family”) or for a vaguely identified, diffuse, or largely abstract entity (e.g., “medicine”).

When intimate altruism was high, anticipated possible effects on intimate others’ welfare seemed to be a decisive factor in participants’ decision-making and behavioral choices. When intimate altruism was low or absent, participants seemed to reject aspects of intimate others’ welfare as matters of personal concern.

Focusing first on high levels of intimate altruism, some participants suggested that their donation attitudes and behaviors stemmed at least in part from desires to avoid a “traditional” funeral for the specific reason that they wanted to save intimate others money, distress, or inconvenience: P70: “To save distress and cost to my children”; P595: “To save the stress of close relatives facing the formality of a ‘grand’ funeral;” P738: “No funeral service hassles … After my death, I don't want to give any troubles to my brother’s family”.

High levels of intimate altruism seemed also to have the potential to reduce the perceived attraction of body donation. Again, this stemmed from participants wanting to limit intimates’ money, distress, or inconvenience. Some participants seemed especially conscious that bodies are sometimes not accepted and that this can place unwelcome and sometimes unexpected burdens on others. In such circumstances, loved ones might quickly have to make alternative disposal arrangements, at personal expense, at a time when they are already likely to be emotionally wrought: P286 “‘No guarantee a body will be accepted’ is scope for expense, anguish, confusion, dissension, stress, complication for … friends and family who survive me;” P398: “Slight anxiety that things may not go smoothly for next-of-kin at the time of offering body for donation”; P821: “Extra stress to family at time of my death”.

When participants were inclined to donate, as most of them were, intimate altruism could nevertheless motivate them to ensure the approval, or at least the acceptance, of those closest to them, or even to give intimates a say in how or indeed whether donation would occur: P208: “I feel it is important that family should be happy about decision to become a body donor”; P667: “I have reservations about keeping parts after 3 years, as my family asked for final closure;” P800: “[Specified relatives] are the most important in my life and whatever they decide is OK by me.”

People can only be altruistic toward intimate others if they have others with whom they are intimate. In a small number of cases, participants explicitly noted that their decisions might have been different had they had living intimates: P218: “Having no near relatives to be concerned about …”; P321: “As I've lost all my close family and friends, a funeral … is not a necessity now.”

Even when participants had intimates, they sometimes dismissed those intimates’ concerns as inappropriate or misplaced: P310: “Some of the extended family will miss a normal funeral. I've told them have a party and … move on”; P483: “My daughters feel they will not have closure - but I have assured them they will.”

Sometimes participants low in intimate altruism actively rejected intimate others’ concerns as not being personally relevant: P288: “Friends or family may disagree, but … are aware of my decision. My relatives would be inconvenienced whatever I decide”; P383: “I would like my family and friends to have minimum knowledge and involvement”; P745: “Family may by upset but it is my wishes and they just have to accept it.”

Although multiple reasons were readily identifiable for medical altruism, reasons for intimate altruism were mostly conspicuous by their absence. While participants often explained the ways in which they wanted to benefit surviving friends and family (i.e., by saving them money, distress, or inconvenience), they rarely gave any explanation for why they wanted to do such things.

Further or alternative concerns

Although relatively rare, some participant concerns seemed distinctive mainly in not being fairly-obviously related to one or other form of “posthumous altruism,” i.e., concern to benefit others after one’s own death: P451: “No danger of being buried or cremated if in very deep coma (stupid thought but a real fear or dread);” P715: “My body might be treated disrespectfully;” P825: “It will, I hope, help me face death”. As with altruistic concerns, though, these “further or alternative concerns” could either foster or impede body donation and their influence appeared often to be only one aspect of networks of motivational concerns.

Discussion

An abductive analysis of hundreds of people’s self-reported thoughts and feelings about body donation suggested that phrases such as “altruism motivates body donation” and “body donation is motivated by altruism,” while true, are potentially misleading.

At least two distinct targets or manifestations of altruism can influence body donation, medical or intimate, as can further or alternative concerns. Body donation is therefore a “multifinal” behavior that is influenced by many motives, as well as being an “equifinal” one because each influencing factor can motivate the behavior without the others being present (Kruglanski et al., Citation2015).

However, factors that are facilitative of donation for some participants were inhibitive for others. Because in the UK and Ireland organ donation typically precludes body donation, medical altruism could inhibit the latter if participants felt that they could better satisfy their motives by becoming organ rather than body donors. In Kruglanski et al. (Citation2015) terms, posthumous organ donation and body donation are “counterfinal” behaviors, i.e., mutually exclusive ones despite each potentially being motivated by the same desire, here the altruistic desire to benefit medicine.

Sub-themes identified within participants’ reasons for medical altruism suggest that the unique circumstances of body donation effectively remove one set of concerns that is often salient during people’s lives. People without beliefs in an afterlife expect that there will be no “self” and therefore no “self-interest” when their altruistic actions are actually “cashed in”. For these participants, positive anticipatory evaluations (i.e., evaluations in the present about anticipated events, Baumgartner et al., Citation2008) sustain their medical altruism, despite not anticipating experiencing anything when or after donation occurs. As some participants said explicitly, in the absence of other motivationally important factors, why not become a body donor if one construes it as a “zero-cost-some-benefit” situation? People making such calculations can enjoy feeling that they are promoting a future that they like thinking about while alive, while also thinking that they will literally have nothing to lose when their good deed is implemented.

Another set of potential inhibitors of body donation are removed if participants are unconcerned about intimate altruism; either because they have no intimates or because they are indifferent about affecting their welfare. While some participants were clear that their intimates’ welfare mattered to them and that these concerns substantially affected their actions, for other participants intimates’ welfare was a matter of personal indifference.

What the discussion above and make clear is that the relationship between altruism and body donation is highly context-dependent and depends on many factors. Although altruism can motivate body donation, it does not always do so, and it is rarely if ever the only motivational concern that prospective donors have (Bolt et al., Citation2010; Olejaz & Hoeyer, Citation2016). This accords with many expected-utility models of decision-making (such as the theory of planned behavior), including those prominent within altruism and prosocial behavior literatures, e.g., the arousal: cost-reward model (Dovidio et al., Citation1991). However, as noted by Batson (Citation1987), decision-makers need not attend all possible concerns and anticipated consequences of all possible actions, even when their deliberation is relatively extensive and calm. In some circumstances, when considered benefits are substantial and considered costs approach zero, decisions are easy and people may wonder what reasons there could be to do anything other than what they decide to do (Ent et al., Citation2020).

The current study is clearly limited in investigating motives for a single behavior using a single cross-sectional data set initially analyzed by a single researcher (Small & Cook, Citation2021). Its findings will obviously be enhanced to the extent that these limitations are addressed. However, theory development is a social and temporal process and, in line with the theory of science adopted by Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967) among others, we consider the claims made in this article only to be the best possible ones at this time, hopefully to be superseded by improved understanding as we and others gather and take into account further data, including others’ empirical and theoretical discoveries.

Even though this study investigated motivations for a single behavior, there are reasons to expect its main findings will be replicable in and generalizable to other populations and behavioral domains (Maxwell, Citation2021). Theoretical and empirical work makes it clear that people can be concerned about the welfare of many things other than narrow self-interest (Batson, Citation1994; Frankfurt, Citation1982); that altruistic concerns can both promote and inhibit the same behavior (Martin & Olson, Citation2013); and that many behaviors which are sometimes and in-part motivated by other-concern are often also or instead motivated by a variety of non-altruistic concerns, including living organ donation (Balliet et al., Citation2019), posthumous organ donation (Guedj et al., Citation2011), and consenting to relatives’ posthumous donation (Darnell et al., Citation2020).

Especially given that survivors of the deceased must implement posthumous donation wishes, the variation of concern shown in the present sample for close others’ interests and welfare suggests that an important area for future research is to seek intimates’ views about their loved ones’ donation preferences. Participants in the current study often noted intimates’ qualms about their decisions (cf. Ahmadian et al., Citation2020). It seems important to know more about intimates’ experiences and actions after their loved ones’ deaths. Do they feel compelled and perhaps resentful at “having” to act against their own personal preferences, or do they perhaps mislead donors into (only) thinking that they will comply with their wishes? The present study highlights the value of being clear about who people seek to be altruistic toward, when, and in what ways. Do body donors’ intimates feel that donors are being suitably altruistic toward them?

Although various reasons for participants’ medical altruism were identified, this was not the case for participants’ intimate altruism. Perhaps participants thought that it was “obvious” why they would want to be considerate of intimates’ welfare and try to protect or promote it (cf, Robinson et al., Citation2019). It remains the case that some participants did not do such things and future research might profitably investigate both reasons for people’s intimate altruism and variance in such altruism. At the risk of repetition, perhaps it is time to move away from questions like “When are people altruistic?” and “Which behaviors are altruistically motivated?” toward questions that attend to detail, nuance, and context, e.g., “When and why are people altruistic in particular ways and to a particular extent towards particular others?” This is likely to have practical as well as theoretical and scientific implications. Recruiting and retaining people willing to become body donors is likely to be more effective, efficient, and ethical to the extent that the specific nature and boundary conditions of their motives are contextually understood.

Disclosure statement

In accordance with Taylor & Francis policy and our ethical obligations as researchers, we are reporting that we have no known potential competing interests.

References

- Ahmadian, S., Khaghanizadeh, M., Khaleghi, E., Zarghami, H., & Ebadi, A. (2020). Stressors experienced by the family members of brain-dead people during the process of organ donation: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 44(12), 759–770. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1609137

- Balliet, W., Kazley, A. S., Johnson, E., Holland-Carter, L., Maurer, S., Correll, J., Marlow, N., Chavin, K., & Baliga, P. (2019). The non-directed living kidney donor: Why donate to strangers? Journal of Renal Care, 45(2), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jorc.12267

- Batson, C. D. (1994). Why act for the public good? Four answers. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 20(5), 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167294205016

- Batson, C. D. (1987). Prosocial motivation: Is it ever truly altruistic? In L. Berkowitz (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 20, pp. 65–122). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0065-2601(08)60412-8

- Baumgartner, H., Pieters, R., & Bagozzi, R. P. (2008). Future‐oriented emotions: Conceptualization and behavioral effects. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(4), 685–696. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.467

- Bolt, S., Venbrux, E., Eisinga, R., Kuks, J. B., Veening, J. G., & Gerrits, P. O. (2010). Motivation for body donation to science: More than an altruistic act. Annals of Anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger: Official Organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft, 192(2), 70–74. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2010.02.002

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 13(2), 201–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Darnell, W. H., Real, K., & Bernard, A. (2020). Exploring family decisions to refuse organ donation at imminent death. Qualitative Health Research, 30(4), 572–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732319858614

- Dovidio, J. F., Piliavin, J. A., Gaertner, S. L., Schroeder, D. A., & Clark, R. D., III, (1991). The arousal: cost-reward model and the process of intervention: A review of the evidence. In M. S. Clark (Ed.), Review of personality and social psychology, Vol. 12. Prosocial behavior (pp. 86–118). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Eisenberg, N., & Miller, P. A. (1987). The relation of empathy to prosocial and related behaviors. Psychological Bulletin, 101(1), 91–119. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.101.1.91

- El Mallah, S. (2020). Conceptualization and measurement of adolescent prosocial behavior: Looking back and moving forward. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 30(S1), 15–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/jora.12476

- Ent, M. R., Sjåstad, H., von Hippel, W., & Baumeister, R. F. (2020). Helping behavior is non-zero-sum: Helper and recipient autobiographical accounts of help. Evolution and Human Behavior, 41(3), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2020.02.004

- Eronen, M. I., & Bringmann, L. F. (2021). The theory crisis in psychology: How to move forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science : A Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 16(4), 779–788. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620970586

- Farsides, T., & Smith, C. F. (2020). Consent in body donation. European Journal of Anatomy, 24(3), 239–248. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/48q3x

- Frankfurt, H. (1982). The importance of what we care about. Synthese, 53(2), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00484902

- Gerring, J. (1999). What makes a concept good? A criterial framework for understanding concept formation in the social sciences. Polity, 31(3), 357–393. https://doi.org/10.2307/3235246

- Glaser, B. G. (1965). The constant comparative method of qualitative analysis. Social Problems, 12(4), 436–445. https://doi.org/10.2307/798843

- Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203793206

- Guedj, M., Sastre, M., & Mullet, E. (2011). Donating organs: A theory-driven inventory of motives. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 16 (4), 418–429. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2011.555770

- Gürses, İ. A., Ertaş, A., Gürtekin, B., Coşkun, O., Üzel, M., Gayretli, Ö., & Demirci, M. S. (2019). Profile and motivations of registered Whole-Body Donors in Turkey: Istanbul University Experience. Anatomical Sciences Education, 12(4), 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/ase.1849

- Habicht, J. L., Kiessling, C., & Winkelmann, A. (2018). Bodies for anatomy education in medical schools: an overview of the sources of cadavers worldwide. Academic Medicine : Journal of the Association of American Medical Colleges, 93(9), 1293–1300. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002227

- Kruglanski, A. W., Chernikova, M., Babush, M., Dugas, M., & Schumpe, B. (2015). The architecture of goal systems: Multifinality, equifinality, and counterfinality in means-end relations. Advances in Motivation Science, 2, 69–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.adms.2015.04.001

- Martin, A., & Olson, K. R. (2013). When kids know better: Paternalistic helping in 3-year-old children. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2071–2081. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031715

- Maxwell, J. A. (2021). Why qualitative methods are necessary for generalization. Qualitative Psychology, 8(1), 111–118. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000173

- McClea, K., & Stringer, M. D. (2010). The profile of body donors at the Otago School of Medical Sciences—Has it changed? New Zealand Medical Journal, 123(1312), 9–17.

- Meslin, E. M., Rooney, P. M., & Wolf, J. G. (2008). Health-related philanthropy: Toward understanding the relationship between the donation of the body (and its parts) and traditional forms of philanthropic giving. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 37(1_suppl), 44S–62S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764007310531

- Mueller, C. M., Allison, S. M., & Conway, M. L. (2021). Mississippi’s whole body donors: Analysis of donor pool demographics and their rationale for donation. Annals of Anatomy = Anatomischer Anzeiger: Official Organ of the Anatomische Gesellschaft, 234, 151673. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aanat.2020.151673

- Olejaz, M., & Hoeyer, K. (2016). Meet the donors: A qualitative analysis of what donation means to Danish whole body donors. European Journal of Anatomy, 20(1), 19–29.

- Robinson, E. L., Hart, B., & Sanders, S. (2019). It’s okay to talk about death: Exploring the end-of-life wishes of healthy young adults. Death Studies, 43(6), 389–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1478913

- Robinson, O. C. (2021). Conducting thematic analysis on brief texts: The structured tabular approach. Qualitative Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1037/qup0000189

- Small, M. L., & Cook, J. M. (2021). Using interviews to understand why: Challenges and strategies in the study of motivated action. Sociological Methods & Research. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124121995552

- Timmermans, S., & Tavory, I. (2012). Theory construction in qualitative research: From grounded theory to abductive analysis. Sociological Theory, 30(3), 167–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/0735275112457914