Abstract

Little is known about those who are widowed while raising dependent children. This study aimed to explore the factors which influence adjustment to partner death. Seven fathers and five mothers were interviewed, and constructivist grounded theory was used. Three interrelated themes were identified: Interpersonal influences, Intrapersonal influences, and Contextual influences. Dependent children meant sole responsibility and increased demands, yet ultimately provided widowed parents a purpose. Participants highlighted the need for increased awareness of young widowhood at a systemic and cultural level, to improve communication around death and young widowhood. Implications included social, financial and therapeutic interventions.

Introduction

The death of a spouse is one of life’s most distressing events (Kim & Kim, Citation2016). Compared to the general population, widowed individuals experience more adverse psychological and physical outcomes (Peña-Longobardo et al., Citation2021). This decline is more pronounced in those widowed at a younger age, who often have no peer group and are less prepared emotionally and practically to cope with loss than older widows (Sasson & Umberson, Citation2014; Scannell-Desch, Citation2003). In the United Kingdom (UK), widowhood typically affects women, with a median age of 76 at widowhood (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2020). Widowhood research has focused on the experience of older, married women (Bennett, Citation2010). Less is known about the experience of young widow(er)s and those unmarried at the time of partner death, despite cohabiting couples constituting a large proportion of the UK population (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2017).

Specific challenges faced by young widow(er)s include navigating pregnancy and parenting alone (Doherty & Scannell-Desch, Citation2008; Glazer et al., Citation2010). Single parents are at a higher risk of poor health and wellbeing outcomes, as well as being more likely to face financial hardship, compared to co-parenting families (Campbell et al., Citation2016; Stack & Meredith, Citation2018). Single parents are often grouped together in research despite varying circumstances (Kroese et al., Citation2021), therefore limited research exists on the unique experience of adjustment for single parents raising dependent children following partner death.

Widowed parents face tasks such as communicating the death to children and managing their children’s grief alongside their own (Sheehan et al., Citation2019). They need to adjust their parenting style as a single person, often taking on roles previously fulfilled by the other parent (Glazer et al., Citation2010). Khosravan et al. (Citation2010) found that Iranian widowed parents developed a paradoxical identity following spousal death: as a hopeless widow and a hopeful mother. This paradoxical identity was referred to as sacrificial parenting, whereby children’s needs and futures were prioritized over their own. Attending to one’s own needs is deemed necessary in developing a positive identity as a single parent (Keating-Lefler & Wilson, Citation2004). The multiple demands of grief and parenting may limit widowed parents’ ability to do this. Increased caregiving demands and parental responsibility in a time of grief constitutes a risk to parents’ wellbeing, as well as their children’s (Falk et al., Citation2021; Yopp & Rosenstein, Citation2012). Conversely, parenting can provide widow(er)s’ with a sense of self-worth and purpose (Edwards et al., Citation2018). Social support can facilitate the transition to single parenthood and support day-to-day demands following spousal death (Glazer et al., Citation2010).

Traditional models are often assumed to demonstrate a linear path of grief, with an expectation of returning to a pre-death state. However, this is rarely the reality of individual experiences (Granek, Citation2015). Recent models conceptualize individual risk and protective factors within the post-death environment, to understand the underlying processes of adjustment (e.g., the contextual resilience framework; Sandler et al., Citation2008; the dual process model [DPM]; Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999). The DPM suggests that effective coping involves oscillation between two processes: loss-orientation (navigating the loss) and restoration-orientation (adjusting to changes and personal growth). It is through these individualized processes that the different tasks of grief are confronted, and at other times avoided. It argues the need for dosage of grieving, whereby respite is fundamental to adaptive coping.

This study aims to increase understanding of young widowhood in the context of parenthood, through exploration of the challenges and factors which facilitate adjustment. This will inform the development of effective interventions to support positive adjustment in widowed parents.

Method

The University of Liverpool Health and Life Sciences Research Ethics Committee approved the study (IPHS-1213-LB-026). The study followed constructivist grounded theory methodology (Charmaz, Citation2006). Grounded theory involves a systematic, inductive, and comparative approach to collecting data for the purpose of constructing theory. Its value, therefore, extends beyond description to interpreting participant meanings, holding explanatory power of the processes apparent in relation to a particular phenomenon (Charmaz, Citation2014). Constructivism acknowledges that multiple perspectives of phenomena may exist in a complex social world. A constructivist approach, therefore, encompasses the reflexivity of the researcher’s perspectives, research situation and social structures (Charmaz, Citation2014). Supervision, a research diary, and memo-writing supported the management of researcher influence upon emerging data and maintained the theory being grounded in widowed parents of dependent children. A widowed parent, expert by experience was actively involved from the beginning of the study and influenced the study’s decision-making processes.

Sample

All participants experienced the death of a romantic partner, at least two years prior to being interviewed. Participants had at least one dependent child (under 16 years) at the time of their partner’s death. Individuals of all sexual orientations, those in unmarried partnerships, adoptive parents, and women who were pregnant at the time of partner death were all included. Informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to being interviewed.

Participants were recruited via a study advert posted on social media pages of widowhood support groups, in supermarkets, and through word of mouth. Recruitment continued until it was considered that the data had reached theoretical saturation. Seven fathers and five mothers who experienced partner death from 2 to 50 years ago participated; all identified as being in heterosexual relationships. Participants experienced both sudden (n = 8) and expected deaths (n = 5), they ranged in age at the time of partner death, from 24 to 51 years old. To ensure anonymity in reporting, participants are identified as P1–P12, followed by their parental role (mother, M or father, F). Participant demographic information is presented in . Grounded theory allows a heterogeneous sample to be recruited through theoretical sampling, allowing multiple perspectives to be included and comparisons between participants examined. Theoretical sampling involved recruiting individuals with a range of timeframes since partner death, differences in marital status, and varying sex, age, and number of children.

Table 1. Participant demographic information.

Data collection and analysis

Information was collected by in-depth, semi-structured interviews, conducted by the first author. Interviews lasting between one and two hours were audio recorded. Face-to-face interviews were conducted in the participant’s own homes or on the university campus. The pandemic of Covid-19 meant that after participant seven, all interviews took place remotely. Questions followed a chronological order to guide discussions, such as: what was life like with [partner]? What were your experiences initially following the death? What helped/were the significant challenges? Reflecting on the time since the death, how do you think being a parent/your gender/age affected your experience?

Data analysis followed a Charmaz (Citation2014) approach, whereby interviews were transcribed and coded prior to subsequent interviews. The interview guide was adjusted accordingly as data collection and analysis progressed, to further explore emerging concepts and inform theoretical sampling. Each transcript was closely read, and each line was coded by the primary author. Low-level, descriptive codes were integrated to describe larger sections of data, known as focused codes. Synthesis of the most prominent focused codes informed higher-level, interpretive concepts. For example, information gathering, acceptance, and reevaluating life beliefs formed the theoretical code of ‘sense-making’. The coding process was iterative, as transcripts were revisited as new codes emerged, this allowed data to progressively become more theoretical in nature (Charmaz & Henwood, Citation2007). A constant comparison approach supported by memo writing and a matrix of focused codes helped to identify when theoretical saturation had been reached. Microsoft Excel was used to support the coding process.

Grounded theory encourages response validation to support theory development (Charmaz, Citation2014). After completion of data collection, three previous participants provided feedback on the theoretical model. This enhanced the credibility of findings and meant that the final model was co-produced by participants as opposed to being a product of the research team alone.

Results

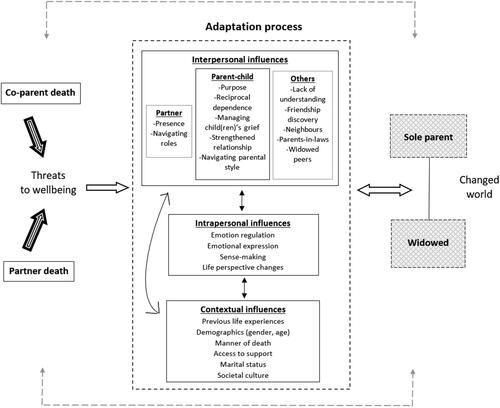

The results gave insights into the experience of grief and adjustment of those widowed while raising dependent children. Participants included both mothers and fathers, who experienced the death of a romantic partner through varying circumstances, 2 to 50 years ago. Deaths included long-term and sudden illnesses, accidental deaths and suicide. Participants were raising one to four children at the time of death, including unborn and adopted children. The death of a partner resulted in a range of threats to participants’ wellbeing, causing disruptions to their identity, mental health, future plans and financial stability. Participants needed to navigate these disruptions to adjust to widowhood and single parenthood. Three interrelated themes were captured in the adjustment process: Interpersonal influences, Intrapersonal influences, and Contextual influences.

Interpersonal influences

Relationships and responses from others following the death impacted the process of adjustment. Children, for example, were viewed as a part of their partner, therefore provided a source of continued connection with them: “They were part of him, part of a reminder, that a little bit of him was still alive, in memory!” (P1M). Maintaining a connection with deceased loved ones is well documented within widowhood literature, including young widow(er)s (Jones et al., Citation2019).

Childcare demands provided a distraction from loss, “you can’t spend your time wallowing for yourself” (P6F). Parenthood gave participants a purpose following the death. Children depended on participants as their only surviving parent, which served as a motivating factor to cope with grief: “You coped because you got no choice… the fact that they were young, the fact that you had to look after them, you had to feed them and care for them and keep them warm and safe” (P1M).

This dependence was reciprocated: “I depended on them for my survival probably as much as they depended on me” (P11F). Parental responsibility protected participants from the adverse psychological effects of loss:

[Having a son] it saved my life. Definitely. I don’t think I’d have been here… In them early days, I remember… the doctor saying to me have you had any thoughts about suicide and I straight away said yes absolutely of course I have, but I’ve got an eight-year-old at home, so it ain’t gonna happen. You—I can guarantee that I would never do that to him. (P7F)

The shared experience of loss ultimately strengthened the relationship participants had with their children: “we’re closer because we were always together” (P1M). Participants described a need to manage their children’s grief alongside their own, an additional demand viewed as unique to being a widowed parent with young children: “They [divorced parents] think their situation is the same as yours, and it so isn’t… You have not got bereaved children to deal with. You haven’t got this twenty-four-seven, fifty-two weeks of the year” (P4M).

Social support that was forthcoming and easily accessible was valued, namely support from neighbors, described as “always knocking asking if you needed anything or to grab you something from the shops” (P12M). On the other hand, some relationships were challenged after the death, as participants experienced a lack of support where it was expected:

You do definitely discover who your real friends are. Some people you just don’t see for dust… you know the ones that you can rely on…. You don’t want to ask for help and they don’t ask you they just do it for you. (P12M)

Participants reflected on how people made comparisons to their own experiences, which was perceived as unhelpful and increased feelings of being misunderstood:

She said I kind of know what you’re going through, I just took my dog to the vets… How can you possibly compare taking your dog to the vet, with a mum and a wife passing away? But people would say the weirdest outlandish things and I’d think you’ve not got, no, you’ve got no clue what you’re on about… just you wait until you lose an actual loved one and then you’ll know the difference between your dog dying, your cat dying and your boyfriend, or your husband or your son dying. There is absolutely, just no comparison you know. (P7F)

Participant’s parents-in-law (their partner’s parents; whether legally married or not) were seen to share in their experience of grief, which appeared to provide them with a source of support that understood the magnitude of their loss: “I saw [wife]’s mum, and they were absolutely destroyed right because that was their daughter” (P3F). Maintaining a connection with their partner’s family after the death was important to maintain a link with the deceased. Furthermore, it was sought on behalf of the children, so they had a continued connection with their deceased parent and vice versa: “[Son]’s all he’s [father-in-law] got you know. Of [wife] left really” (P7F). Parents-in-law were also discussed as a vital source of childcare following the death, which supported sole parenthood.

Participants came to value relationships with widowed others following the death. Peer support facilitated positive adjustment through shared understanding, shared thinking and interconnectedness: “I think the only way you understand grief is by feeling it” (P11F). Having “a black humor to death” (P2F) was discussed as key in peer communication, potentially demonstrating a safe way for widow(er)s to express grief. This supports previous findings of the benefits of peer-support and humor in widowhood (Holmgren, Citation2019; Lund et al., Citation2008). Unhelpful responses from others served to strengthen connections between widowed individuals, as a sense of division exists between the widowed and non-widowed, suggested by P4M: “the widowed community call the non-widowed muggles”.

Intrapersonal influences

Intrapersonal processes impacted adjustment, such as participants being able to speak openly about their distress and make sense of the death. In bereavement, a range of emotions was experienced: “I yo-yo’d… between absolute fury with him, and then devastation at his loss” (P4M). Engaging with distressing emotions was emphasized as important in processing grief: “you’ve got to go through it in order to get around it” (P8M). An enduring need to manage fears, emotions and reconstruct beliefs was emphasized: “I don’t think I’ll ever get over it. I think I’ll just learn to live with it” (P3F). This demonstrates the non-linear nature of grief and the ongoing process of adjustment.

Participants agreed that expressing grief was helpful in positive adjustment: “I just found it [blogging] the most… relieving thing in the world to do! To get it out of my head” (P7F). Participants benefited from speaking out about their grief, or, regretted that they had not shared enough: “If I had been able to share more closely what I felt… been able to offload a bit that would have helped” (P6F). This subsequently influenced their parenting, as participants acknowledged that being transparent about death and distress was an important part of managing the children’s grief and their own: “If you think you’re withholding something from a child on the basis you’re protecting them, you’re not. You should always be transparent” (P3F).

Participants reported themselves as wholly changed because of their loss: “I’m not the same person that I was” (P9F). Part of the adjustment process was to make sense of the loss and adapt to a “new you” (P2F). Information gathering was important in making sense of the death: “I got the medical notes, I got the post-mortem, I got the BNF [British National Formulary] book…” (P3F). This was more apparent in those participants who had experienced sudden losses such as P5F: “You’re just so blown away by how unjust it is… I contacted erm a solicitor’s firm because I couldn’t understand how they didn’t spot the cancer”. Being informed, as well as accountability had implied importance within the sense-making process. An acknowledgement and acceptance of the death were described as important within the sense-making process and in moving forward:

I know of widows who still, 5 years down the line are still struggling… Because they can’t let go… they haven’t gone through the process right to come out of the other end and accept that it’s a thing now, that they’ve gone. (P9F)

Participants endeavored to live a full and happy life from their experiences, described as the “widows’ mantra” (P9F):

You’ve got one life to live, so go and live it!… it’s not so much that losing them frees you, you just realise that they went through their lives not doing certain things themselves… You can’t be like that anymore. You’ve got to do the things you want to do because you might get run over by a bus tomorrow and they’re gone. (P9F)

As P9 showed, a sense of liberation was experienced. By coming to terms with and making sense of the loss, participants were able to focus on achieving a meaningful life despite death. Participants spoke of activities and life decisions never considered possible before. This speaks to meaning-making that is grounded in action, which Armour (Citation2003) described as “living in ways that give purpose to the loved one’s death” (p. 526). Haase and Johnston (Citation2012) also found meaning-making to be an important coping mechanism for young widows (see also Neimeyer, Citation1998, Citation2005).

Contextual influences

The circumstances surrounding bereavement, including previous life experiences, impacted the process of adjustment and influenced inter- and intra- personal processes. The experience of previous losses and challenging life events was perceived as helpful in coping with partner bereavement. As stated by P8M, “I think in terms of that resilience… it was already there”. Older parents, compared to younger parents discussed advantages of increased life experience to adjusting to sole parenthood:

It was much easier for me to give up all of my own stuff because I’d had so many years of doing it before …you know I don’t think I would have been able to be as dedicated to my kids [if younger] (P10M)

Early life experiences were also identified as influential in navigating sole parenting and participant’s ability to express emotions:

I just think it was the way I was brought up. We weren’t the sort of family who openly shared our feelings or showed our emotions. And I think some of that rubbed off on me…. I tried not to be the father that my father was to me. (P6F)

These findings suggest that life experiences prior to becoming widowed and a sole parent impacts adjustment. van Wielink et al. (Citation2020) noted life experiences preceding the loss are formative, which influence individual response to change and loss. Fathers, in particular, discussed struggles with adjustment. This may have been due to the significance attributed to and absence of the mother figure: “I think you do look at mum as being you know sort of the lynch pin of a family and it’s very difficult not having that” (P5F). “Women are more geared up to the emotional side than men are… more sensitive to do it, so I’ve had to soften, myself, and that’s been a challenge” (P3F). This suggests mothers and fathers have different experiences following partner death, which supports previous findings of gender differences in widowhood (Lee et al., Citation2001). Fathers shared the perspective that single parent families tend to be mothers, which negatively impacted their experiences, as they often felt judged:

I used to feel I’d have to be twice as good as single mum to be taken seriously as a dad. I didn’t think anybody thought a man was capable of bringing up children… in most situations, if a family split, kids are with the mum, that was the way of the world (P6F)

UK statistics show that women account for 86% of lone parents with dependent children (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2016). This suggests that the unexpected occurrence of being a sole father posed additional challenges for widowed fathers.

The processes of sense-making and acceptance were identified as being more difficult for participants who had witnessed partner distress and deterioration prior to their death, such as through long-term illness (see also Prigerson et al., Citation2003; Stroebe et al., Citation2007): “It’s really hard watching someone you love die… to me, you would be much better to have a full and active life and then just go. As to fight a battle you’re going to lose” (P2F). The (in)ability to preserve a positive image of their partner was problematic. P3M, for example, witnessed his wife’s suffering in hospital and stated: “some of the images I’m continually haunted by”. This highlights the relational nature between the circumstances surrounding the death and intrapersonal processes.

Following the death, all participants had to navigate financial management, yet varying support from employers impacted their experiences. For example:

She said [boss], well the leave policy says that you can have a week’s paid leave for a family crisis, or, if you want to have longer you have to book it as a holiday, or, take it as sick leave if you can get doctor’s note. And I just thought are you having a laugh? (P4M).

This differed from P11F, who had a positive experience from his employer:

I received a phone call from HR and they just said look are you ok to speak this is literally just a personal phone call, we want to know how you are and if there’s anything we can do to help. So I explained the situation and they just said look- we’re going to pay your basic salary for 6 months you call us when you’re ready.

P11F later added that his employer also supported him in a work role change and adjusted his working hours to better suit sole parenthood. The level of support from employers impacted the financial stability of participants, which in turn impacted their wellbeing. Employers that allowed time off work following the death, allowed participants time to grieve and better adjust to their new roles.

Marital status impacted access to financial support, as unmarried participants were not entitled to bereavement support from the UK government: “You know all of these things… piled on just because we weren’t married” (P10M). This highlights the inherent political importance placed on marriage within the UK society.

Participants discussed the role of sociocultural attitudes toward death, describing society as naïve and suggesting that “we don’t prepare for death as a society” (P8M). A lack of societal understanding was problematic, as participants felt unable to connect with others to express their grief: “We [widow(er)s] are a beacon to the reality that this can happen, and people are shy of it. So they don’t know how to communicate with you” (P8M).

In UK society, death and dying are not openly discussed (Department of Health, Citation2008). Participants discussed how being widowed at a younger age further affected this: “it’s awkward as hell you know when you do meet people because no-one expects it” (P10M). It is acknowledged that cohort effects may have also impacted participants' experiences, given the large time frame since partner death (2-50 years ago).

Discussion

The findings lend support for a preliminary model, which highlights the underlying processes and influential factors in the adjustment following partner death while raising dependent children. The model presents the significance of the death by the dual roles of the deceased: partner and co-parent. The death threatened participants’ physical and psychological wellbeing. To move forward from these threats to wellbeing, participants navigated a process of adjustment. The concept of adaptation best captured the experience of adjusting to a changed world following a loss. The process of adaptation was associated with survival and was influenced by interpersonal, intrapersonal and contextual factors. The model does not provide a timeframe for ‘normal’ recovery as in some models, as this overlooks variability in response to loss and can elicit unhelpful responses from others (Wortman & Silver, Citation1989). Instead, it demonstrates the importance of context, unique to each individual. The model shares features with Sandler et al. (Citation2008)’s contextual resilience framework, which also attempts to understand the processes underlying adaptation and bereavement outcomes. It, too, emphasizes the role of environmental and individual-level risk and protective factors in changes following death ().

Participants felt misunderstood by society, which strengthened relations with people with shared experiences of bereavement (children, parents-in-law and widowed peers). Despite an overwhelming sense of sole responsibility, dependent children provided participants a purpose to survive and move forward after loss. They also provided a present connection with their deceased partner. The strengthened parent-child relationship centered on reciprocal dependence, which may reflect a factor unique to those widowed with dependent children. Children provided surviving parents purpose, distraction and companionship, which indicates the ways in which dependent children can support bereaved parents. In contrast, Ha et al. (Citation2006) found that older widowed parents’ dependence on adult children was centered on financial, legal and practical support after loss. Children were a key motivator in transitioning adversity into a meaningful story, which gives insight into the underlying interactions between the inter- and intra- personal adaptive processes.

Parents described being equally dependent on their children, which provided some protection from the adverse psychological effects of grief. In the absence of a co-parent, the death prompted participants to reflect on their early experiences, including their own experiences of being parented, which shaped their approach to sole parenting. The influence of early experiences supports the attachment theory and the impact of loss on attachment patterns (Bowlby, Citation1969, Citation1973).

Participants felt that facing loss and engaging with their grief was important for positive adaptation. Emotion regulation and expression facilitated this process, which in turn were influenced by early experiences and access to outlets to express their grief. Outlets for grief, such as peer support, humor and blogging, were considered helpful in alleviating overwhelming feelings caused by grief.

Finding meaning in suffering was prominent within participants’ narratives, emphasizing a shift from surviving to thriving following partner death. This supports the need to reconstruct a world of meaning that has been challenged by loss (Neimeyer, Citation1998; Neimeyer et al., Citation2010). Sense-making is recognized as an interpersonal as well as an intrapersonal process, as meaning is embedded in socially and culturally constructed belief systems (Shotter, Citation1997).

The findings highlighted sociocultural expectations of parents, which differed for mothers and fathers. Additionally, societal expectations of lone parents being mothers was shared as an additional challenge that widowed fathers faced. UK statistics show that both widowed individuals and single parents are more likely to be women (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2016, Citation2020). This gave insight into the qualitatively different experiences of widowed fathers. This matches quantitative findings by Edwards et al. (Citation2018), who found that widowed fathers reported high parental pressures and perceived inadequacies in raising children without a mother.

Social and financial support reduced the demands on the participants and supported the management of everyday stressors. This supports the DPM’s process of oscillation, where grief is at times avoided and at other times confronted (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999). The DPM argues that respite from stressors of grief is needed for adaptive coping.

The current study addresses a gap in the research, where limited literature is available on young widowhood and even less so on young, widowed parents. Theoretical sampling allowed for a range of individual circumstances and demographics to be included, allowing for the exploration of similarities and differences in participant experiences. This supported the development of a detailed theoretical explanatory model. The study highlighted a unique challenge unmarried widow(er)s face in accessing financial support after partner death. Limitations included the study’s small sample size, lack of ethnic diversity and being a self-selected sample. Most widowhood research involves people of White ethnicity and from the majority ethnic group. Incorporating participants from diverse backgrounds may provide insights into different cultural, religious, or spiritual beliefs which could influence experiences. This is further emphasized by the importance ascribed to sociocultural expectations of grief and parenting in the current study. Further research involving participants who were not legally married to their partners at the time of death, would allow further exploration of the unique challenges this population face. It would be valuable to explore the experiences of individuals in same-sex relationships, and raising children at the time of partner death, to better support this underrepresented group.

Implications

The findings suggest adaptation to loss is best understood by recognizing a range of dynamic influential factors (interpersonal, intrapersonal and contextual). This highlights the need for a holistic, multifaceted approach in providing support to widowed parents. The findings provide insights into the processes by which widowed parents make sense of partner death: tolerating distress, acquiring information, and adjusting life perspectives to cope with life where loss is a reality. Psychological intervention could provide an outlet for the expression of grief, support sense-making, and promote values-based living. Interpersonally, peer-support groups could provide validation, practical and emotional support. Services could help family and friends to better understand and therefore support widowed parents, through offering interventions such as psychoeducation around death. The shared loss with one’s children also suggests the importance of systemic interventions that focus on the family unit. In the UK, individual and family support following death is currently available through third sector services such as Bereavement UK and Care for The Family. Increased collaboration between services such as these and the NHS would help to ensure effective support is widely accessible. At a cultural level, systemic changes are needed to challenge taboo subjects such as death and young widowhood. Community initiatives and media campaigns could raise awareness of the issues that young widow(er)s face, including sole parenting. Being able to express one’s grief was considered helpful within adjustment, services should therefore provide and utilize platforms that enable this (e.g. social media).

Unmarried participants faced increased challenges, such as restricted access to financial bereavement support. Current UK legislation denies unmarried widowed parents’ entitlement to financial support (UK Government, Citation2021a). The findings emphasize the value of financial support in adapting to life as a widowed parent, therefore urges the government to acknowledge the impact of social circumstances and give more consideration to the economic drivers of distress. Establishing social and financial support systems that reduce everyday demands would help to ensure the wellbeing of widowed parents and the wellbeing of their children. This could include the introduction of standardized compassionate leave entitlement for widowed parents of dependent children, which does not currently exist in the UK (UK Government, Citation2021b) ().

Table 2. Summary of implications.

Conclusion

Dependent children presented a range of additional challenges for widow(er)s to navigate, while managing their own grief. Yet children ultimately provided a purpose, which motivated parents to survive and adapt to life after loss. The impact of sociocultural attitudes of widowhood and single parents were highlighted as influencing the adjustment process. Differences existed within mothers’ and fathers’ experiences, but all participants spoke of current life with pride and a sense of personal growth due to their experiences. This study enhances understanding the experiences of young, widowed parents and how they adapt to one of life’s most distressing events. From this, more effective interventions can be developed to support this deserving population.

Acknowledgments

We thank profusely the widow(er)s who participated in the study, who shared their stories so openly. It was a privilege to hear your experiences, which showed the strength that is possible in the face of one of life’s most distressing events.

Disclosure statement

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Armour, M. (2003). Meaning making in the aftermath of homicide. Death Studies, 27(6), 519–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180302884

- Bennett, K. M. (2010). “You can't spend years with someone and just cast them aside”: Augmented identity in older British widows. Journal of Women & Aging, 22(3), 204–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2010.495571

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss. Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Attachment and loss: Separation anxiety and loss. Basic Books.

- Campbell, M., Thomson, H., Fenton, C., & Gibson, M. (2016). Lone parents, health, wellbeing and welfare to work: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Bmc Public Health, 16(188), 188–110. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-2880-9

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. SAGE Publications.

- Charmaz, K. (2014). Constructing grounding theory. (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications.

- Charmaz, K., & Henwood, K. (2007). Grounded theory in psychology. In C. Willig & W. Stainton-Rogers (Eds.), Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology. (pp. 238–256). SAGE Publications.

- Department of Health (2008). End of life care strategy: Promoting high quality care for all adults at the end of life. National Health Service.

- Doherty, M. E., & Scannell-Desch, E. (2008). The lived experience of widowhood during pregnancy. Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health, 53(2), 103–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmwh.2007.12.004

- Edwards, T. P., Yopp, J. M., Park, E. M., Deal, A., Biesecker, B. B., & Rosenstein, D. L. (2018). Widowed parenting self-efficacy scale: A new measure. Death Studies, 42(4), 247–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1339743

- Falk, M. W., Angelhoff, C., Alvariza, A., Kreicbergs, U., & Sveen, J. (2021). Psychological symptoms in widowed parents with minor children, 2-4 years after the loss of a partner to cancer. Psycho-oncology, 30(7), 1112–1118. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5658

- Glazer, H. R., Clark, M. D., Thomas, R., & Haxton, H. (2010). Parenting after the death of a spouse. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 27(8), 532–536. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909110366851

- Granek, L. (2015). The psychologization of grief and its depictions within mainstream North American media. Springer Publishing.

- Ha, J. H., Carr, D., Utz, R. L., & Nesse, R. (2006). Older adults' perceptions of intergenerational support after widowhood: How do men and women differ? Journal of Family Issues, 27(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X05277810

- Haase, T. J., & Johnston, N. (2012). Making meaning out of loss: A story and study of young widowhood. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 7(3), 204–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2012.710170

- Holmgren, H. (2019). Life came to a full stop: The experiences of widowed fathers. Journal of Death and Dying, 84(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222819880713

- Jones, E., Oka, M., Clark, J., Gardner, H., Hunt, R., & Dutson, S. (2019). Lived experience of young widowed individuals: A qualitative study. Death Studies, 43(3), 183–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1445137

- Keating-Lefler, R., & Wilson, M. E. (2004). The experience of becoming a mother for single, unpartnered, Medicaid-eligible, first-time mothers. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 36(1), 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1547-5069.2004.04007.x

- Khosravan, S., Salehi, S., Ahmadi, F., & Sharif, F. (2010). A qualitative study of the impact of spousal death on changed parenting practices of Iranian single-parent widows. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal, 12(4), 388–395.

- Kim, Y., & Kim, C.-S. (2016). Will the pain of losing a husband last forever? The effect of transition to widowhood on mental health. Development and Society, 45(1), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.21588/dns/2016.45.1.007

- Kroese, J., Bernasco, W., Liefbroer, A. C., & Rouwendal, J. (2021). Growing up in single-parent families and the criminal involvement of adolescents: A systematic review. Psychology of Crime and Law, 27(1), 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2020.1774589

- Lee, G. R., DeMaris, A., Bavin, S., & Sullivan, R. (2001). Gender differences in the depressive effect of widowhood in later life. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(1), S56–S61. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.1.s56

- Lund, D. A., Utz, R., Caserta, M. S., & de Vries, B. (2008). Humor, laughter, and happiness in the daily lives of recently bereaved spouses. Omega, 58(2), 87–105. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.58.2.a

- Neimeyer, R. (1998). Lessons of loss: A guide to coping. McGraw-Hill.

- Neimeyer, R. (2005). Grief, loss, and the quest for meaning: Narrative contributions to bereavement care. Bereavement Care, 24(2), 27–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682620508657628

- Neimeyer, R. A., Burke, L. A., Mackay, M. M., & van Dyke Stringer, J. G. (2010). Grief therapy and the reconstruction of meaning: From principles to practice. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9135-3

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2016). Lone parents with dependent children by marital status of parent, by sex, UK: 1996 to 2015. Retreived from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/adhocs/005660loneparentswithdependentchildrenbymaritalstatusofparentbysexuk1996to2015

- Office for National Statistics (ONS). (2017). Families and households in the UK: 2017. Retreived from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/families/bulletins/familiesandhouseholds/2017#:∼:text=growing%20the%20fastest-,In%202017%20there%20were%2019.0%20million%20families%20in%20the%20UK,most%20common%20type%20of%20family.

- Office for National Statistics (ONS) (2020). Average age of becoming a widow(er): Estimates using the ONS longitudinal study, England and Wales, 1997 to 2017. Retreived from: https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/adhocs/11434averageageofbecomingawidowerestimatesusingtheonslongitudinalstudyenglandandwales1997to2017

- Peña-Longobardo, L. M., Rodríguez-Sánchez, B., & Oliva-Moreno, J. (2021). The impact of widowhood on wellbeing, health, and care use: A longitudinal analysis across Europe. Economics and Human Biology, 43, 101049–101013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ehb.2021.101049

- Prigerson, H. G., Cherlin, E., Chen, J. H., Kasl, S. V., Hurzeler, R., & Bradley, E. H. (2003). The stressful caregiving adult reactions to experiences of dying (SCARED) scale: A measure for assessing caregiver exposure to distress in terminal care. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 11(3), 309–319. https://doi.org/10.1097/00019442-200305000-00008

- Sandler, I., Wolchik, S., & Ayers, T. (2008). Resilience rather than recovery: A contextual framework on adaptation following bereavement. Death Studies, 32(1), 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180701741343

- Sasson, I., & Umberson, D. J. (2014). Widowhood and depression: New light on gender differences, selection, and psychological adjustment. The Journals of Gerontology. Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 69(1), 135–145. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt058

- Scannell-Desch, E. (2003). Women's adjustment to widowhood. Theory, research, and interventions. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 41(5), 28–36. https://doi.org/10.3928/0279-3695-20030501-10

- Sheehan, D. K., Hansen, D., Stephenson, P., Mayo, M., Albataineh, R., & Anaba, E. (2019). Telling adolescents that a parent has died. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing, 21(2), 152–159. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000506

- Shotter, J. (1997). The social construction of our inner selves. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 10(1), 7–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/10720539708404609

- Stack, R. J., & Meredith, A. (2018). The impact of financial hardship on single parents: An exploration of the journey from social distress to seeking help. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 39(2), 233–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10834-017-9551-6

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Stroebe, W. (2007). Health outcomes of bereavement. The Lancet, 370(9603), 1960–1973. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61816-9

- UK Government (2021a). Bereavement Support Payment. Retreived from: https://www.gov.uk/bereavement-support-payment

- UK Government (2021b). Time off for family and dependents. Retrieved from: https://www.gov.uk/time-off-for-dependants

- van Wielink, J., Wilhelm, L., & van Geelen-Merks, D. (2020). Loss, grief, and attachment in life transitions: A clinician's guide to secure base counselling. Routledge.

- Wortman, C. B., & Silver, R. C. (1989). The myths of coping with loss. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 57(3), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.57.3.349

- Yopp, J. M., & Rosenstein, D. L. (2012). Single fatherhood due to cancer. Psycho-oncology, 21(12), 1362–1366. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.2033