Abstract

Research over the past several decades suggests that meaningful psychedelic experiences can engender long-term effects on subjective wellbeing. However, less research has investigated the psychological mechanisms through which these effects may emerge. In the present study, participants (N = 201) completed an online survey that retrospectively measured the acute effects of a meaningful psychedelic experience, as well as changes in subjective well-being and death anxiety. Reductions in death anxiety significantly mediated the effects of mystical experience on satisfaction with life, positive affect, and negative affect. Reductions in death anxiety did not mediate any of the effects of psychological insight. Although correlational, the findings are consistent with the hypothesis that some of the benefits of psychedelic-induced mystical experiences on subjective well-being may emerge due to reductions in death anxiety. Nevertheless, further research is needed to establish a causal effect of reduced death anxiety on well-being in the context of psychedelic experiences.

There has been a resurgence of interest into potential clinical applications of psychedelics over the past several decades. The potential therapeutic effects of psychedelics are increasingly becoming the focus of empirical research (Andersen et al., Citation2021); however, research into the underlying mechanisms that may drive the salutary effects of psychedelics is still in its infancy. Furthermore, research has focused predominantly on clinical applications, with the potential benefits of psychedelic use in naturalistic settings being less studied (Jungaberle et al., Citation2018). Further research into the outcomes of psychedelic experiences is important as psychedelic use is increasing in many countries worldwide (e.g., Chan et al., Citation2022; Livne et al., Citation2022). For instance, recent research suggests that past year use of psychedelics in the USA increased from 1.7% of the population aged 12 years and older in 2002 to 2.2% in 2019 (Livne et al., Citation2022). The main aim of the present study was to investigate reduced death anxiety as a mechanism underpinning the relationship between acute psychedelic effects and improved subjective well-being.

Therapeutic effects of psychedelics

Serotonergic hallucinogens, otherwise known as psychedelics, are a class of psychoactive substances that alter mood, cognitive processes, and perception (Nichols, Citation2016). The most common psychedelics include lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), psilocybin, mescaline, and dimethyltryptamine (DMT; Nichols, Citation2016). In addition to a growing body of work providing preliminary evidence that psychedelic use in clinical contexts may be efficacious for the treatment of a range of psychological disorders (Andersen et al., Citation2021), there may also be a link between psychedelic experiences and more general increases in well-being (Gandy, Citation2019).

Although research is still unpacking why psychedelic experiences might improve subjective well-being, Yaden and Griffiths (Citation2021) review substantial evidence suggesting that the subjective psychedelic experience may be key to their benefits (although see Olson, Citation2020). While psychedelics produce a range of subjective effects, there has been a specific research focus on what has been dubbed the “psychedelic-occasioned mystical experience,” which involves phenomenological components such unity with the external world, a loss of sense of space and time, ineffability, and self-transcendent emotions such as awe (Barrett et al., Citation2015). Although correlational, many studies have now found a positive relationship between the strength of the psychedelic-occasioned mystical experience and the positive outcomes of psychedelic experiences (see Yaden & Griffiths, Citation2021).

In addition to mystical experiences, there has also been a recent focus on the role of psychological insight in psychedelic experiences (Davis et al., Citation2021; Peill et al., Citation2022). The development of personal insight into one’s cognition, behaviors and personal histories is a goal in many psychotherapeutic modalities (Jennissen et al., Citation2018). Davis et al. (Citation2020) recently developed the Psychological Insights Questionnaire (PIQ), which measures ostensible insights into one’s relationships and both maladaptive and adaptive patterns of cognition, emotion, and behavior. The measure builds on earlier work arguing that personal insight may be a key mechanism underpinning the beneficial effects of psychedelics (Pahnke et al., Citation1970; Roseman et al., Citation2017). Davis et al. (Citation2020) found that scores on the PIQ predicted self-reported improvements in depression and anxiety following a psychedelic experience. Similarly, Davis et al. (Citation2021) found that the PIQ predicted changes in well-being following a psychedelic experience, and that it uniquely predicted changes in well-being while controlling for mystical experience (as measured by the Mystical Experience Questionnaire; MEQ).

Psychedelics and death anxiety

In addition to a growing focus on how the acute subjective effects may contribute to longer-term therapeutic effects of psychedelics, research has also begun to consider longer term mediators of the benefits of psychedelics. To this end, a range of “general factors” that might underpin broad therapeutic benefits of psychedelics have been discussed, including increased connectedness (Carhart-Harris et al., Citation2018), meaning in life (Hartogsohn, Citation2018) and psychological flexibility (Davis et al., Citation2020). In contrast to these perspectives, an additional mechanism through which salutary effects of psychedelics may occur is through reductions in death anxiety (Moreton et al., Citation2020), as psychedelic experiences have been found to produce significant reductions in death anxiety in people with advanced or terminal cancer (Reiche et al., Citation2018; Ross, Citation2018), as well as physically healthy people (Griffiths et al., 2018, Griffiths et al., Citation2019).

Although little research has specifically investigated the mechanisms through which psychedelics may reduce death anxiety, there are several candidate mechanisms. Grof (Citation1973) suggested that many of the most profound therapeutic effects of psychedelics stem from the experience of unity, which is the result of an intense sense of agony and death, followed by a sense of rebirth. Conceptual similarities between “ego death” during psychedelic experiences and physical death are also supported by Timmermann et al. (Citation2018) who reported similarities between the acute effects of DMT and near-death experiences (NDEs). Notably, NDEs have been shown to beneficially alter attitudes toward death (Noyes, Citation1980). Moreton et al. (Citation2020) argue that death-like experiences resulting from psychedelics are in line with the principles of “flooding”: a therapeutic technique in which individuals are exposed to their fears directly and all at once. In a similar vein, meta-analytic findings show that deliberate exposure to death-related situations (such as through exposure therapy) significantly reduce death anxiety (Menzies et al., Citation2018). Thus, the reduced death fears following psychedelic experiences may be explained by this subjective confrontation with death that can occur during psychedelic-occasioned mystical experiences.

Similarly, psychological insights during psychedelic experiences might also reduce death anxiety, in the same way that they have been associated with self-reported reductions in general anxiety (Davis et al., Citation2020). Engaging in meaning-seeking and meaning-making processes to better understand oneself and resolve issues in one’s life is argued to be important to overcoming death anxiety (Tomer, Citation1992; Wong, Citation2007). Indeed, therapies centered on meaning-making have been effective in decreasing death anxiety among patients with advanced cancer (e.g., Lo et al., Citation2014). For instance, insights that facilitate a clearer self-concept, make sense of death, or make life seem purposeful, can make death seem less threatening (Tomer, Citation1992; Wong, Citation2007). These types of insights are common during psychedelic experiences (Davis et al., Citation2020; Citation2020). Furthermore, death anxiety is associated with avoidant coping and reactive emotional processing (e.g., Arena et al., Citation2022; Grant & Wade-Benzoni, Citation2009), suggesting that insights into maladaptive cognitive, emotional, or behavioral patterns could help to reduce the avoidant and reactive processes that maintain death anxiety.

If psychedelics do typically reduce fears of death, this has implications for their therapeutic efficacy as research suggests a link between death anxiety and subjective well-being (Fortner & Neimeyer, Citation1999). Building on the work of existential psychotherapists (e.g., May, Citation1967; Yalom, Citation2008), death anxiety has also been argued to be a transdiagnostic construct involved in many manifestations of psychopathology (Arndt et al., Citation2005; Iverach et al., Citation2014). Consistent with this, significant large correlations have been found between death anxiety and the symptom severity of at least 12 different disorders (Menzies et al., Citation2019). Furthermore, reminders of death have been shown to exacerbate avoidance behaviors in specific phobias and social anxiety (Strachan et al., Citation2007), compulsive handwashing in obsessive-compulsive disorder (Menzies & Dar-Nimrod, Citation2017), and body checking and reassurance seeking in anxiety-related conditions such as panic disorder and illness anxiety (Menzies et al., Citation2021). These experimental findings support the notion that death anxiety not only covaries with well-being, but may be the “worm at the core” (James, Citation1902/1985, p. 119) underlying much psychological suffering.

The present study

Research suggests that psychedelic experiences can lead to enduring increases in subjective well-being (Gandy, Citation2019) and have the potential to reduce death anxiety (Moreton et al., Citation2020; Pahnke, Citation1969; Reiche et al., Citation2018). However, no empirical research has examined whether changes in attitudes toward death mediate the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. The current retrospective study aimed to explore whether reduced death anxiety mediated the relationship between the acute effects of meaningful psychedelic experiences (i.e., psychological insights and mystical experiences), and changes in subjective well-being. Research suggests that meaningful experiences from psychedelics are common, with a majority of individuals who take psychedelics in supportive settings rating the experience as one of the most meaningful experiences of their lives (Griffiths et al., Citation2006; Johnson et al., Citation2017). We hypothesized that:

H1: There would be significant increases in subjective well-being from time one (T1; before a meaningful psychedelic experience) to time two (T2; currently);

H2: There would be significant decreases in death anxiety from T1 to T2;

H3: The strength of the psychedelic-occasioned mystical experience would significantly predict improvements in subjective well-being from T1 to T2;

H4: Ostensible psychological insights during a psychedelic experience would significantly predict improvements in subjective well-being from T1 to T2;

H5: Mystical experience would significantly predict changes in death anxiety from T1 to T2;

H6: Ostensible psychological insights would significantly predict changes in death anxiety from T1 to T2; and

H7: There would be significant indirect effects of mystical experience and psychological insights on changes in subjective well-being through decreases in death anxiety from T1 to T2.

Method

Participants and design

Recruitment occurred through a series of targeted advertisements on social media. These included various Facebook groups and Reddit forums focusing on psychedelic experiences. The inclusion criteria were being 18 years or over, having previously taken at least one psychedelic drug (e.g., LSD, DMT, ayahuasca, mescaline or psilocybin) that elicited a meaningful experience in any type of setting, and being fluent in English. A total of 656 participants clicked the URL and landed on the first page of the survey (participant information statement), which stated that the study was investigating meaningful psychedelic experiences but did not reveal the specific aims or hypotheses. In total, 527 participants provided informed consent; of these, 284 participants were excluded for not completing the entire survey. A further seven participants were excluded for not passing an attention check placed approximately a quarter of the way through the survey that required participants to select “Strongly Agree” if they were paying attention. An additional 35 participants were excluded from the present analysis for reporting having had the meaningful experience within the past week or more than ten years ago. This resulted in a final sample of 201 participants.

Participants first completed basic demographics. Next, they were instructed to recall a particularly meaningful psychedelic experience. Participants then completed a set of measures relating to what occurred during that experience. Following this, they answered another set of measures relating to how they were in the past before that particular psychedelic experience. The wording varied according to how long ago the participant had indicated that the experience was. For instance, if their chosen experience occurred in “these last 3 years,” they answered the questions about how they thought they were three years ago before the experience. After these measures, participants then completed the same set of questions, but re-worded to now measure how they were at the current point in their life. Lastly, participants had the opportunity to enter a draw to win one of two Amazon gift vouchers ($100 AUD). Data was collected between 15 June 2020 and 3 September 2020. All procedures were approved by the University of Wollongong Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2020/149).

Measures

Measures of the psychedelic experience

Mystical experience

The Mystical Experience Questionnaire-30 (MEQ30; Barrett et al., Citation2015) comprises four factors: Mystical-type experiences (e.g., feelings of unity and sacredness), Positive mood, Transcendence of time and space, and Ineffability. Each item was rated on a 6-point scale from 0 (none, not at all) to 5 (extreme [more than any other time in my life and stronger than 4]). In the current study, the average score across the entire scale was used, as per recommendations that this is most appropriate when there are no specific hypotheses about the individual factors (Barrett et al., Citation2015). Previous studies have demonstrated the internal reliability of the total item scale (Davis et al., Citation2020), and there was excellent internal consistency in the current sample (α = .92).

Psychological insight

The Psychological Insight Questionnaire (PIQ; Davis et al., Citation2020) measures ostensible psychological insights during a psychedelic experience. Participants were asked to reflect on their chosen experience with a psychedelic and to rate the intensity of 28 insight experiences during the reported experience (e.g., “awareness of uncomfortable or painful feelings I previously avoided”) on a 6-point Likert-type scale (0 = none; not at all to 5 = extreme; more than ever before in my life). A mean score on these items was computed. The internal consistency in the current sample was excellent (α = .95).

Pre-post measures

Life satisfaction

The Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., Citation1985) is a five-item questionnaire that measures the cognitive component of subjective well-being (e.g., “the conditions in my life are excellent”). Participants rate each item on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). A mean score was calculated, with higher scores indicating greater life satisfaction. The scale was asked from the perspective of before the participant’s meaningful psychedelic experience, as well as from their current perspective. When using total scores, Diener et al. (1985) describe the following categories: 30–35 (Extremely Satisfied), 25–29 (Satisfied), 20–24 (Slightly satisfied), 15–19 (Slightly Dissatisfied), 10–14 (Dissatisfied) and 5–9 (Extremely Dissatisfied). In a review of research using the SWLS, Pavot and Diener (Citation2009) noted that although there was significant variance in mean scores across populations, most samples reviewed had a mean between 23 and 28. The SWLS has been shown to be a reliable measure of life satisfaction (Vassar, Citation2008). Previous research by Davis et al. (Citation2021) using a similar retrospective design (with a focus on an “insightful experience”) found changes in SWLS mean scores (Mchange = 1.15) from before to after the experience. In the current sample, the internal consistency was good for both pre (α = .89) and post (α = .87) SWLS scores.

Subjective wellbeing

The Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al., Citation2010) was used to assess the affective component of subjective well-being. The SPANE has 12 items, of which six assess positive affect and six assess negative affect. Participants are asked to rate how often they experience various emotions (e.g., pleasant, afraid), with each item rated on a scale from 1 (very rarely or never) to 5 (very often or always). When rating each of the emotions, the questions were asked from the perspective of before their meaningful psychedelic experience, as well as how the participant generally feels at this current point in their life. The SPANE yields a positive affect score as well as a negative affect score, and both subscales have been shown to have good internal consistency (Diener et al., Citation2010). Previous research on college students found total score normative means of 22.05 (SD = 3.73) for positive affect and 15.36 (SD = 3.95) for negative affect (Diener et al., Citation2010) In the present study, an average score was calculated for each respondent. In the current sample, internal consistencies of the two subscales were good for both pre and post positive affect (α’s = .89), and pre (α =.86) and post (α = .84) negative affect.

Death anxiety

The Death Attitude Profile-Revised—Fear of Death Subscale (DAP-R; Wong et al., Citation1994) was used to measure death anxiety. Each of the seven items (e.g., “the prospect of my own death arouses anxiety in me”) is rated on a scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Prior studies have demonstrated the good internal consistency and construct validity of the DAP-R (Zuccala et al., Citation2022). Wong et al. (Citation1994) reported normative means of 3.25 (18–29 years old), 3.10 (30–59 years old) and 2.72 (60–90 years old) for the Fear of Death Subscale. In the current sample, there was excellent internal consistency for both pre and post (α’s = .92). Recently, Sweeney et al. (Citation2022) used the DAP-R in a study with a similar retrospective design and found an average change score of −2.13 from before to after a psychedelic experience on the Fear of Death Subscale.

Results

Demographics

Demographics and aspects of the meaningful experience can be seen in . The mean age was 32.90 years (SD = 11.47). In total, 116 participants identified as male, 78 as female, six as another gender, and one selected “prefer not to say.”

Table 1. Descriptive table of demographic variables.

Changes in subjective well-being and fear of death

First, we were interested in assessing the number of participants who reported increases or decreases in subjective well-being or death anxiety from T1 to T2. In total, 87.06% reported increases in satisfaction with life, 9.95% reported decreases, and 2.99% reported no change. Regarding positive affect, 79.60% reported an increase, 11.44% reported a decrease, and 8.96% reported no change. When negative affect was examined, 81.01% reported a decrease, 9.95% reported an increase, and 8.96% reported no change. Regarding death anxiety, 79.10% reported a decrease, 16.92% reported an increase, and 3.98% reported no change.

Next, we were interested in whether there were overall changes in subjective well-being and fear of death averaged across the sample. Four one-way repeated-measures analyses of variance (ANOVAs) were conducted to compare participants’ subjective well-being and death anxiety before a meaningful psychedelic experience and currently (see ). There were significant improvements in mean scores from before to after a meaningful psychedelic experience for all variables. For satisfaction with life, the average total (summed) scores of participants moved from 19.44 (in the “Slightly dissatisfied” range) to 29.70 (in the “Satisfied” range).

Table 2. Changes in fear of death and subjective well-being.

Correlations between study variables

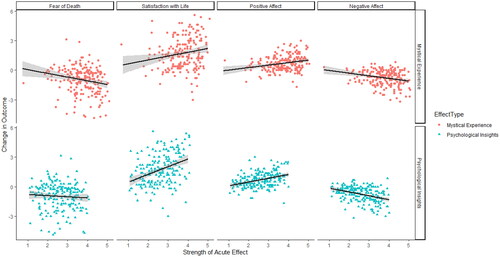

A bivariate correlational analysis was used to determine the strength of the relationship between the acute effects, and changes in subjective well-being and death anxiety (see and ). Mystical experience and psychological insight were moderately positively correlated. Mystical experience showed small to moderate correlations with increased subjective well-being (all measures) and decreased fear of death. Psychological insight was moderately correlated with increased subjective well-being (all measures) but did not significantly correlate with changes in fear of death.

Figure 1. Relationships between acute subjective effects, and changes in fear of death and subjective well-being measures.

Table 3. Pearson’s bivariate correlations between study variables.

Mediation analyses

Six separate mediation models were conducted to test for the effects of psychological insights and mystical experience on satisfaction with life, positive affect, and negative affect through fear of death. Model 4 on PROCESS (Hayes, Citation2022) was used with 5000 bootstrapped samples on the indirect effect and 95% confidence intervals. Mystical experience and psychological insight were entered alternatively as the independent variable and covariate to ascertain the unique effects of each of these aspects of the psychedelic experience. For all mediation analyses, non-standardized regression coefficients were calculated. As seen in , there were significant indirect effects of mystical experience on all three measures of subjective well-being through changes in fear of death. There were no significant indirect effects of psychological insight through fear of death.

Table 4. Total, direct, and indirect effects of mystical experience and psychological insight.

Discussion

The present retrospective cross-sectional study aimed to investigate whether: (a) there would be retrospective increases in subjective well-being and decreases in death anxiety following a meaningful psychedelic experience (H1/H2); (b) psychedelic-occasioned mystical and insight experiences would correlate positively with changes in subjective well-being (H3/H4); these acute psychedelic effects would correlate with reductions in death anxiety (H5/H6); and whether reductions in death anxiety would mediate the relationship between acute subjective effects and improved subjective well-being (H7). Overall, the results were largely consistent with these hypotheses.

In support of H1 and H2, most participants reported increases in subjective well-being and decreases in fear of death from before the chosen psychedelic experience to “presently”. This is not surprising given that the study specifically only sampled participants who had had a self-described personally meaningful experience. Nevertheless, the present data is consistent with prior evidence (e.g., Griffiths et al., Citation2006) that psychedelic experiences can lead to longer term changes in these constructs. In support of H3 and H4, both mystical experience and psychological insights significantly predicted increases in all three measured facets of subjective well-being. Interestingly, when both mystical experience and psychological insight were included in a model together, insight was a stronger predictor on all three measures of subjective well-being. In support of H5, mystical experience significantly predicted reduced death anxiety. However, in contrast to H6, psychological insight did not. While there were no indirect effects of psychological insight on subjective well-being through reduced fear of death, there was a significant indirect effect of mystical experience, thus providing partial support for H7.

Psychedelics and well-being

Although limited by a retrospective design, the present findings are consistent with the suggestion that psychedelic experiences have the potential to lead to longer term changes in subjective well-being in specific instances. The finding that the strength of the mystical experience predicted self-reported changes in well-being was not surprising and dovetails with an expansive body of studies documenting salutary effects of mystical experiences (Yaden & Griffiths, Citation2021). The finding that psychological insights was related to changes in well-being also adds to a small number of recent studies using this measure that have found psychological insights during a psychedelic experience to predict changes in anxiety and depression (Davis et al., Citation2020; Fauvel et al., Citation2021) and subjective well-being (Davis et al., Citation2021). Interestingly, in the present study, the predictive effects of mystical experience on subjective well-being became nonsignificant when controlling for the effects of psychological insight, suggesting that insight may be a more robust predictor of changes in well-being.

Psychedelics and death anxiety

The present findings are also consistent with growing research suggesting that psychedelic experiences can often reduce death anxiety. The finding that mystical experience predicted self-reported changes in death anxiety is consistent with earlier suggestions by Pahnke (Citation1969) and Grof (Citation1972) that acute psychedelic effects have the potential to change fundamental attitudes, including those regarding death.

The finding that psychological insight did not predict reduced death anxiety was unexpected. Ostensive insights into the nature of consciousness or the meaning of life have been suggested to play a role in why psychedelics might reduce death anxiety and psychological distress (Moreton et al., Citation2020). However, the current finding converges with a similar recent study that found the MEQ-30 predicted reduced death anxiety, while the PIQ did not (Moreton et al., Citation2022). Additionally, the present study replicated this finding using a different measure of death anxiety to that used by Moreton et al. (Citation2022; Collett-Lester Fear of Death Scale—Death of Self subscale). As Moreton et al. (Citation2022) suggest, the lack of predictive power of the PIQ could be due to the narrow breadth of its content domain, which assesses insights into one’s relationships and adaptive or maladaptive cognitions, emotions and behaviors, with little to no content pertaining to philosophical insights into the nature of consciousness or the ultimate meaning of life. Nonetheless, the PIQ does contain themes of increased interpersonal connection and, to a small degree, insights regarding how to live meaningfully—both of which have been found to predict reduced death anxiety (e.g., Florian & Mikulincer, Citation1998; Routledge & Juhl, Citation2010). Moreton et al. (Citation2020) have suggested that changes in these constructs may partially explain why psychedelics can decrease death anxiety. Thus, it is interesting and unexpected that the PIQ did not predict changes in death anxiety.

The present findings suggest that mystical experiences may be important for reducing death anxiety but shed little insight on the mechanisms through which mystical experience may reduce death anxiety. There are many reasons why this may be the case, including that mystical experiences frequently involve exposure to death-like experiences, and decrease focus on the self (which is a necessary precondition for death anxiety; Pyszczynski et al., Citation1990). The exact psychological mechanisms through which psychedelics reduce death anxiety is an understudied area and, as noted by Yaden and Griffiths (Citation2021), there are likely a multitude of cognitive and affective pathways through which the effects of psychedelic-induced mystical experiences may emerge.

The mediating role of death anxiety

As psychological insight did not predict self-reported change in death anxiety, it was not surprising that change in death anxiety did not mediate the relationship between psychological insight and change in well-being. However, change in death anxiety was a significant mediator of the relationship between mystical experience and change in well-being. This may indicate that the mechanisms by which mystical experience exerts its effect on well-being are more related to reductions in death anxiety than the equivalent mechanisms for psychological insights (at least as measured by the PIQ). While this study cannot provide definitive answers to the mechanisms underlying the positive effects of psychedelics, it does reinforce the value in pursuing death anxiety as one potential mechanism of these effects.

Limitations and future research

The present study provides evidence of associations between acute subjective effects of psychedelics, death anxiety and well-being. Although the significant correlations are consistent with what would be expected if causal relations existed, caution should be taken in interpreting the reported associations in a causal manner. For instance, it is possible that changes in well-being might in fact drive changes in death anxiety. Alternatively, the relationship might be driven by changes in other unmeasured confounding factors, such as changes in connectedness or meaning in life, subsequently resulting in changes in both death anxiety and well-being.

A limitation of retrospective designs is that accurate recall could be compromised by the passage of time. Measuring from the perspective of before the experience to the present meant that for some participants, a significant amount of time had passed. On one hand, this might imply that the benefits of the meaningful experience last for many years. On the other hand, the significant passage of time for some participants might have compromised accurate recall, as well as introduced noise due to life events in the intervening time-period. Limitations in memory might also be compounded by motivational biases in the self-selected sample. It is plausible that the population of people who would volunteer to participate in the present study would be positively predisposed to psychedelics, and this may have affected the results. It was for this reason that the study did not aim to attempt to make conclusions about psychedelic experiences in general and limited the sampling to “meaningful experiences,” as it was anticipated that there would be a positive bias in the sampling of participants willing to participate in studies about psychedelics.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to estimate the proportion of psychedelic experiences in naturalistic settings that lead to meaningful experiences, as respondents of voluntary online surveys do not typically constitute a representative sample. As such, it needs to be acknowledged that the present study captures a subset of psychedelic experiences and further research is needed to further understand the effects of non-meaningful or, indeed, negative psychedelic experiences on death anxiety. In a similar vein, consideration needs to be given to the large drop-out rate of the present study, which may have affected the results due to nonrandom attrition, thus further skewing the results. The drop-out rate also meant that, while the sample size was not small, the study was insufficiently powered to detect small associations (e.g. r = .10; power = 0.8, α = .05).

Further research is needed into the effects of psychedelics on death anxiety. There remain several questions that need further clarification: (a) what proportion of psychedelic experiences lead to reductions in death anxiety; (b) how long do these effects typically last; and (c) what are the causal factors that determine whether psychedelic experiences reduce death anxiety? Further research is needed into how reduced death anxiety as a result of psychedelic use might mediate the beneficial effects of psychedelics. For instance, Moreton et al. (Citation2022) found that reduced death anxiety was related to reduced obsessions and compulsions following a meaningful psychedelic experience. In a similar vein, future research could investigate whether reduced death anxiety might also mediate the therapeutic effects of psychedelics on other disorders in which death anxiety is implicated.

Recent research has seen a focus on psychological insights in the context of psychedelic experiences. However, the PIQ has a relatively narrow content domain—being limited to insights into relationships and adaptive or maladaptive cognitions, emotions, and behaviors. Further work is needed to develop measures of insight that also capture insights into metaphysical, religious, and spiritual domains, given their theoretical potential to contribute to some of the salutary effects of psychedelics. Recent work by Timmermann et al. (Citation2021) suggests that psychedelic experiences may typically lead to changes in metaphysical beliefs—specifically, moving from a materialist to some form of non-materialist worldview. It has previously been suggested that changed beliefs around the nature of consciousness might explain the effects of psychedelics on death anxiety (Moreton et al., Citation2020) and, as such, a measure of psychological insights that captures ostensible metaphysical insights may more strongly predict changes in death anxiety following psychedelic experiences.

Future research may also consider diverse forms of well-being that may be affected as a result of reduced death anxiety following psychedelic experiences. While the present study focused on subjective or hedonic well-being, there is likely to be value in considering effects on eudemonic well-being, which emphasizes a sense of personal growth and meaning or purpose (Ryan & Deci, Citation2001; Ryff, Citation2014). Both psychedelic experiences and the resolution of issues pertaining to death anxiety have been tied to improvements in these types of well-being (e.g., Griffiths et al., Citation2006, Citation2008; May, Citation1967; Yalom, Citation1980), and future research might consider the role of reduced death anxiety in mediating the effects of psychedelic experiences on eudemonic well-being.

Conclusion

Early psychedelic researchers (e.g., Pahnke, Citation1969) speculated that that psychedelic-induced mystical experience could have profound effects on people’s relationship with death. Concurrently, researchers and psychotherapists from the existential tradition were developing ideas suggesting that death anxiety may be the “worm at the core” (James, Citation1902/1985, p. 119) of much psychological dysfunction (Becker, Citation1973; Yalom, Citation1980). The present study found that reductions in death anxiety mediated the effects of psychedelic-induced mystical experiences on changes in subjective well-being. Although retrospective, the present study provides a foundation for further research testing reduced death anxiety as a causal factor involved in the benefits of psychedelics, and helps guide further research into why, how, and for whom psychedelics may reduce death anxiety.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andersen, K. A., Carhart‐Harris, R., Nutt, D. J., & Erritzoe, D. (2021). Therapeutic effects of classic serotonergic psychedelics: A systematic review of modern‐era clinical studies. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 143(2), 101–118. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.13249

- Arena, A. F., MacCann, C., Moreton, S. G., Menzies, R. E., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2022). Living authentically in the face of death: Predictors of autonomous motivation among individuals exposed to chronic mortality cues compared to a matched community sample. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221074160

- Arndt, J., Routledge, C., Cox, C. R., & Goldenberg, J. L. (2005). The worm at the core: A terror management perspective on the roots of psychological dysfunction. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 11(3), 191–213.

- Barrett, F. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2015). Validation of the revised Mystical Experience Questionnaire in experimental sessions with psilocybin. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 29(11), 1182–1190. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881115609019

- Becker, E. (1973). The denial of death. Free Press.

- Carhart-Harris, R., Erritzoe, D., Haijen, E., Kaelen, M., & Watts, R. (2018). Psychedelics and connectedness. Psychopharmacology, 235(2), 547–550. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-017-4701-y

- Chan, G., Sun, T., Lim, C., Yuen, W. S., Stjepanović, D., Rutherford, B., Hall, W., Johnson, B., & Leung, J. (2022). An age-period-cohort analysis of trends in psychedelic and ecstasy use in the Australian population. Addictive behaviors, 127, 107216.

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., & Griffiths, R. R. (2020). Psychological flexibility mediates the relations between acute psychedelic effects and subjective decreases in depression and anxiety. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 15, 39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2019.11.004

- Davis, A. K., Barrett, F. S., So, S., Gukasyan, N., Swift, T. C., & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). Development of the Psychological Insight Questionnaire among a sample of people who have consumed psilocybin or LSD. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 35(4), 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120967878

- Davis, A. K., Clifton, J. M., Weaver, E. G., Hurwitz, E. S., Johnson, M. W., & Griffiths, R. R. (2020). Survey of entity encounter experiences occasioned by inhaled N, N-dimethyltryptamine: Phenomenology, interpretation, and enduring effects. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 34(9), 1008–1020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881120916143

- Diener, E. D., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71–75.

- Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D-w., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97(2), 143–156.

- Fauvel, B., Strika-Bruneau, L., & Piolino, P. (2021). Changes in self-rumination and self-compassion mediate the effect of psychedelic experiences on decreases in depression, anxiety, and stress. Psychology of Consciousness: Theory, Research, and Practice, https://doi.org/10.1037/cns0000283

- Florian, V., & Mikulincer, M. (1998). Symbolic immortality and the management of the terror of death: the moderating role of attachment style. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 725–734. https://doi.org/10.1037//0022-3514.74.3.725

- Fortner, B. V., & Neimeyer, R. A. (1999). Death anxiety in older adults: A quantitative review. Death studies, 23(5), 387–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899200920

- Gandy, S. (2019). Psychedelics and potential benefits in “healthy normals”: A review of the literature. Journal of Psychedelic Studies, 3(3), 280–287. https://doi.org/10.1556/2054.2019.029

- Grant, A. M., & Wade-Benzoni, K. A. (2009). The hot and cool of death awareness at work: Mortality cues, aging, and self-protective and prosocial motivations. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 600–622.

- Griffiths, R. R., Hurwitz, E. S., Davis, A. K., Johnson, M. W., & Jesse, R. (2019). Survey of subjective “God encounter experiences”: Comparisons among naturally occurring experiences and those occasioned by the classic psychedelics psilocybin, LSD, ayahuasca, or DMT. Plos one, 14(4), e0214377. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0214377

- Griffiths, R. R., Johnson, M. W., Richards, W. A., Richards, B. D., Jesse, R., MacLean, K. A., Barrett, F. S., Cosimano, M. P., & Klinedinst, M. A. (2018). Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 32(1), 49–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117731279

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., Johnson, M. W., McCann, U. D., & Jesse, R. (2008). Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. Journal of Psychopharmacology (Oxford, England), 22(6), 621–632. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881108094300

- Griffiths, R. R., Richards, W. A., McCann, U., & Jesse, R. (2006). Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacology, 187(3), 268–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-006-0457-5

- Grof, S. (1972). Varieties of transpersonal experiences: Observations from LSD psychotherapy. The Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 4(1), 45.

- Grof, S. (1973). Theoretical and empirical basis of transpersonal psychology and psychotherapy: Observations from LSD research. Journal of Transpersonal Psychology, 5(1), 15–53.

- Hartogsohn, I. (2018). The Meaning-Enhancing Properties of Psychedelics and Their Mediator Role in Psychedelic Therapy, Spirituality, and Creativity. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 12, 129. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2018.00129

- Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (3rd ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Iverach, L., Menzies, R. G., & Menzies, R. E. (2014). Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical psychology Review, 34(7), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.09.002

- James, W. (1902/1985). The varieties of religious experience: A study in human nature. Harvard University Press.

- Jennissen, S., Huber, J., Ehrenthal, J. C., Schauenburg, H., & Dinger, U. (2018). Association between insight and outcome of psychotherapy: systematic review and meta-analysis. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 175(10), 961–969. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2018.17080847

- Johnson, M. W., Garcia-Romeu, A., & Griffiths, R. R. (2017). Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 43(1), 55–60. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2016.1170135

- Jungaberle, H., Thal, S., Zeuch, A., Rougemont-Bücking, A., von Heyden, M., Aicher, H., & Scheidegger, M. (2018). Positive psychology in the investigation of psychedelics and entactogens: A critical review. Neuropharmacology, 142, 179–199. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuropharm.2018.06.034

- Livne, O., Shmulewitz, D., Walsh, C., & Hasin, D. S. (2022). Adolescent and adult time trends in US hallucinogen use, 2002–19: any use, and use of ecstasy, LSD and PCP. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 117(12), 3099–3109. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.15987

- Lo, C., Hales, S., Jung, J., Chiu, A., Panday, T., Rydall, A., Nissim, R., Malfitano, C., Petricone-Westwood, D., Zimmermann, C., & Rodin, G. (2014). Managing Cancer And Living Meaningfully (CALM): phase 2 trial of a brief individual psychotherapy for patients with advanced cancer. Palliative medicine, 28(3), 234–242.

- May, R. (1967). The meaning of anxiety. (Revised ed.). W.W Norton.

- Menzies, R. E., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2017). Death anxiety and its relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000263

- Menzies, R. E., Sharpe, L., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2021). The effect of mortality salience on bodily scanning behaviors in anxiety-related disorders. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 130(2), 141–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000577

- Menzies, R. E., Sharpe, L., & Dar‐Nimrod, I. (2019). The relationship between death anxiety and severity of mental illnesses. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(4), 452–467.

- Menzies, R. E., Zuccala, M., Sharpe, L., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2018). The effects of psychosocial interventions on death anxiety: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 59, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.09.004

- Moreton, S. G., Burden-Hill, A., & Menzies, R. E. (2022). Reduced death anxiety and obsessive beliefs as mediators of the therapeutic effects of psychedelics on obsessive compulsive disorder symptomology. Clinical Psychologist, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13284207.2022.2086793

- Moreton, S. G., Szalla, L., Menzies, R. E., & Arena, A. F. (2020). Embedding existential psychology within psychedelic science: reduced death anxiety as a mediator of the therapeutic effects of psychedelics. Psychopharmacology, 237(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00213-019-05391-0

- Nichols, D. E. (2016). Psychedelics. Pharmacological reviews, 68(2), 264–355. https://doi.org/10.1124/pr.115.011478

- Noyes, R. Jr. (1980). Attitude change following near-death experiences. Psychiatry, 43(3), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/00332747.1980.11024070

- Olson, D. E. (2020). The subjective effects of psychedelics may not be necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), 563–567.

- Pahnke, W. N. (1969). The psychedelic mystical experience in the human encounter with death. Harvard Theological Review, 62(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0017816000027577

- Pahnke, W. N., Kurland, A. A., Unger, S., Savage, C., & Grof, S. (1970). The experimental use of psychedelic (LSD) psychotherapy. JAMA, 212(11), 1856–1863. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.1970.03170240060010

- Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2009). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. In Assessing well-being (pp. 101–117). Springer.

- Peill, J. M., Trinci, K. E., Kettner, H., Mertens, L. J., Roseman, L., Timmermann, C., Rosas, F. E., Lyons, T., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2022). Validation of the Psychological Insight Scale: A new scale to assess psychological insight following a psychedelic experience. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 36(1), 31–45.

- Pyszczynski, T., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., & Hamilton, J. (1990). A terror management analysis of self-awareness and anxiety: The hierarchy of terror. Anxiety Research, 2(3), 177–195.

- Reiche, S., Hermle, L., Gutwinski, S., Jungaberle, H., Gasser, P., & Majić, T. (2018). Serotonergic hallucinogens in the treatment of anxiety and depression in patients suffering from a life-threatening disease: A systematic review. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 81, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.09.012

- Roseman, L., Nutt, D. J., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2017). Quality of acute psychedelic experience predicts therapeutic efficacy of psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Frontiers in Pharmacology, 8, 974. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphar.2017.00974

- Ross, S. (2018). Therapeutic use of classic psychedelics to treat cancer-related psychiatric distress. International Review of Psychiatry, 30(4), 317–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540261.2018.1482261

- Routledge, C., & Juhl, J. (2010). When death thoughts lead to death fears: Mortality salience increases death anxiety for individuals who lack meaning in life. Cognition and Emotion, 24(5), 848–854.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual review of Psychology, 52(1), 141–166.

- Ryff, C. D. (2014). Psychological well-being revisited: Advances in the science and practice of eudaimonia. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 83(1), 10–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353263

- Strachan, E., Schimel, J., Arndt, J., Williams, T., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (2007). Terror mismanagement: Evidence that mortality salience exacerbates phobic and compulsive behaviors. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1137–1151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207303018

- Sweeney, M. M., Nayak, S., Hurwitz, E. S., Mitchell, L. N., Swift, T. C., & Griffiths, R. R. (2022). Comparison of psychedelic and near-death or other non-ordinary experiences in changing attitudes about death and dying. PloS one, 17(8), e0271926. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0271926

- Timmermann, C., Kettner, H., Letheby, C., Roseman, L., Rosas, F. E., & Carhart-Harris, R. L. (2021). Psychedelics alter metaphysical beliefs. Scientific reports, 11(1), 1–13.

- Timmermann, C., Roseman, L., Williams, L., Erritzoe, D., Martial, C., Cassol, H., Laureys, S., Nutt, D., & Carhart-Harris, R. (2018). DMT models the near-death experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1424. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.01424

- Tomer, A. (1992). Death anxiety in adult life—theoretical perspectives. Death studies, 16(6), 475–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189208252594

- Vassar, M. (2008). A note on the score reliability for the Satisfaction With Life Scale: An RG study. Social Indicators Research, 86(1), 47–57.

- Wong, P. T. (2007). Meaning management theory and death acceptance. In Existential and spiritual issues in death attitudes (pp. 91–114). Psychology Press.

- Wong, P. T., Reker, G. T., & Gesser, G. (1994). Death attitude profile-revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. Death anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation, and Application, 121, 121–148.

- Yaden, D. B., & Griffiths, R. R. (2021). The subjective effects of psychedelics are necessary for their enduring therapeutic effects. ACS pharmacology & Translational Science, 4(2), 568–572. https://doi.org/10.1021/acsptsci.0c00194

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy (Vol. 1). Basic Books New York.

- Yalom, I. D. (2008). Staring at the sun: Overcoming the terror of death. The Humanistic Psychologist, 36(3–4), 283–297. https://doi.org/10.1080/08873260802350006

- Zuccala, M., Menzies, R. E., Hunt, C. J., & Abbott, M. J. (2022). A systematic review of the psychometric properties of death anxiety self-report measures. Death studies, 46(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1699203