Abstract

This systematic review aimed to examine the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality in adults, and the impact of death anxiety interventions on the capability for suicide and suicidality. MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science were extensively searched using purpose-related keywords from the earliest to July 29th, 2022. A total of 376 participants were included across four studies which met inclusion. Death anxiety was found to relate significantly and positively with rescue potential, and although weak, negatively with suicide intent, circumstances of attempt, and a wish to die. There was no relationship between death anxiety and lethality or risk of lethality. Further, no studies examined the effects of death anxiety interventions on the capability for suicide and suicidality. It is imperative that future research implements a more rigorous methodology to establish the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality and establish the impacts of death anxiety interventions on the capability for suicide and suicidality.

Suicide ranks among the top 10 causes of death in most Western countries, with more than 800,000 individuals across all ages dying by suicide each year (World Health Organization, Citation2018). Suicidology research has shown that despite the vast number of individuals who think about suicide, only a small subset of these individuals will progress to a suicide attempt (Chu et al., Citation2017). Guiding our understanding of factors associated with the progression from suicide desire to the suicide attempt, The Interpersonal Psychological Theory of Suicide (IPTS; Joiner, Citation2005; Van Orden et al., Citation2010) has received the largest amount of attention in the suicidology literature. According to IPTS, thwarted belongingness and perceived burdensomeness create a desire for suicide. To engage in a serious or lethal suicide attempt, however, an individual must possess an increased fearlessness of death and pain insensitivity (acquired capability). While the IPTS-acquired capability has remained unchanged, it is hereafter termed capability for suicide to account for the “non-acquired” genetic vulnerability factors often associated with capability for suicide trajectory (for a review see Smith & Cukrowicz, Citation2010).

To test IPTS’ capability for suicide framework, Ma et al. (Citation2016) conducted a systematic review examining the relationship between capability for suicide, suicidal ideation, and suicide attempts. Of 21 studies, nine reported a non-significant relationship between capability for suicide and suicide ideation. However, across 12 studies, the capability for suicide was found to significantly predict suicidal ideation, suicide risk, suicide potential, and suicidality. A similar pattern was observed between capability for suicide and suicide attempts, with four of nine studies reporting a non-significant relationship, and five studies reporting that capability for suicide significantly predicted suicide attempts and self-injurious behaviors. In another systematic and meta-analytic review, the capability for suicide was found to be significantly related (albeit weakly) to suicidal ideation and suicide attempts (Chu et al., Citation2017).

Overall, the growing literature raises questions about the robustness of the interaction between the “desire to die” and “capability for suicide” constructs for the progression from suicidal ideation to attempt. These mixed findings may further suggest that additional capability factors may be limiting our ability to understand factors associated with the progression from suicide ideation to the suicide attempt. Consistent with this, despite improving prevention and treatment strategies suicide rates has remained relatively unchanged in the past 50 years (Franklin et al., Citation2017).

Terror management theory and death anxiety

Three decades of empirical Terror Management Theory research (TMT, for a review, see Greenberg, Citation2012) has demonstrated that a fear of death lies at the root of a wide array of everyday human behavior (Burke et al., Citation2010). TMT argues, however, that the development of adaptive coping mechanisms, or “anxiety buffers” (e.g., self-esteem, attachment, and cultural worldviews) enable most humans to function with minimal overt death anxiety (Iverach et al., Citation2014). For some, however, genetic predispositions and adverse experiences may result in the inability to effectively cope with this fear, lending to maladaptive coping mechanisms (e.g., avoidance) and increased psychological vulnerability (Iverach et al., Citation2014).

Death anxiety has been proposed as a transdiagnostic construct suggested to account for high rates of comorbidity across mental health disorders (Iverach et al., Citation2014; Juhl & Routledge, Citation2016; Menzies & Dar-Nimrod, Citation2017; Menzies et al., Citation2019). Consistent with this, Menzies et al. (Citation2019) demonstrated that death anxiety was associated with symptom severity of 12 psychological disorders (Menzies et al., Citation2019). Experimental studies have similarly provided support for the role of death anxiety as a central driver of body checking and reassurance seeking among individuals with somatic symptom-related disorders (Noyes et al., Citation2002), avoidance among individuals with social anxiety and spider phobias (Strachan et al., Citation2007), and increased handwashing among individuals with obsessive-compulsive disorder (Menzies & Dar-Nimrod, Citation2017).

Death anxiety and low fearlessness of death

Often used synonymously, death anxiety and fear of death are two distinct theoretical constructs (Castano et al., Citation2011; Lehto & Stein, Citation2009). Despite sharing some overlapping features, the conceptualization and psychological diagnosis, and treatment of fear and anxiety (e.g., phobic versus anxiety disorders) are distinguished by emotional reactions to “real” versus “apprehension/imagined” threat, respectively (Daniel-Watanabe & Fletcher, Citation2022). Throughout death anxiety research, death anxiety is often conceptualized but not limited to, a fear of one’s own death, the deaths of others, the process of dying, and fear of the unknown (Saleem et al., Citation2015; Zuccala et al., Citation2022). Conversely, Joiner (Citation2005) and Van Orden and colleagues (Citation2010) describe IPTS’ fearlessness of death construct as the specific fearlessness of death to one’s own death by suicide.

While numerous inventories measuring death anxiety in response to one’s own death have been developed, there is increasing support for the multidimensional nature of death anxiety. The commonly used Death Anxiety Scale (Templer, Citation1970) has been shown to have a diverse factor structure, further providing support for, and lending researchers to conceptualize death anxiety as a multidimensional construct (Cai et al., Citation2017; Iverach et al., Citation2014). Throughout the capability for suicide literature however, the most widely used measure of capability for suicide, the Acquired Capability for Suicide Scale – Fearlessness of Death (Ribeiro et al., Citation2014) consists of merely one item specific to one’s own death (e.g., the prospect of my own death arouses anxiety in me), a clear distinction from the suggested multifaceted nature of death anxiety. Thus, while fearlessness of death and death anxiety may share similarities, empirically they are conceptualized and measured as distinct constructs.

Death anxiety and suicidality

An extensive body of research has established a relationship between psychopathology and maladaptive coping methods such as suicidality (Scocco et al., Citation2000; Spitzer et al., Citation2018; Velkoff & Smith, Citation2019), although the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality remains an understudied area of research.

Lester (Citation1967) is often credited as having first examined the relationship between the fear of death and suicide potential. In a sample of 43 adolescent students, Lester (Citation1967) found that those who had attempted or threatened suicide were less fearful of death than non-suicidal individuals. Several studies have similarly reported a negative or non-significant relationship between death anxiety and aspects of suicidality. In a sample of 50 adults admitted to the hospital following a recent suicide attempt, Tarter et al. (Citation1974) found no relationship between death anxiety and the number of previous suicide attempts. Goldney (Citation1981) examined correlates of lethality in a sample of 110 adults with a recent suicide attempt, the results indicated lesser death anxiety among those with higher suicide intent. Stiluon et al. (Citation1984) administered 198 students the Death Concern Scale (Dickstein, Citation1972) and 10 vignettes detailing scenarios in which consideration of suicide may increase (i.e., a breakup, death of a loved one, etc). The study found that individuals with higher death concern disagreed with suicidal actions more often than those with lower death concern.

In contrast, however, several studies have suggested that a positive relationship between death anxiety and aspects of suicide may exist. Minear and Brush (Citation1981) found that in a sample of 394 students, those who had strongly considered a suicide attempt endorsed greater anxiety about death. Similarly, in a sample of 62 adolescents and adults, those with greater potential for suicide were more apprehensive about death (D’Attilio & Campbell, Citation1990). Research by Orbach et al. (Citation1993) examined varying levels of fear about death scores and suicide potential in 24 psychiatric and suicidal individuals, 20 psychiatric and non-suicidal, and 27 non-psychiatric and non-suicidal control individuals. Among the psychiatric and suicidal group, a negative correlation was found between the total fear of death score and suicide potential, indicating greater the suicide potential the less fear of death. Among the psychiatric and non-suicidal group, fear of death was found to be unrelated to suicide potential. Notably, in the control group, greater fear of death scores positively correlated with suicide potential, indicating that the greater potential for suicide, the greater the fear of death.

Overall, these mixed results may offer some insights regarding death anxiety and aspects of suicidality. For example, four of the studies examined the relationship among individuals with a reported suicide history and failed to find any relationships. In contrast, three studies found that among individuals with no reported suicide history, a greater fear of death was associated with a greater endorsement of suicidality. However, the findings should be considered in light of their various limitations. The small sample sizes of some of the included studies may suggest that the studies were underpowered, thus limiting the ability to find small to moderate effects. Secondly, of the seven studies, only five included a validated measure of death anxiety, and just three studies included validated suicide measures, which limits the reliability of any conclusions drawn.

The current review

Growing research on death anxiety and its role in psychopathology has led some researchers to propose that death anxiety should be considered in both the conceptualization and treatment of mental health (Furer et al., Citation2007; Iverach et al., Citation2014; Menzies & Dar-Nimrod, Citation2017). Meta-analytic findings have demonstrated that death anxiety can be ameliorated with treatment, although the impacts of such treatments on other symptoms of psychopathology (e.g., suicidality) remain unclear (Menzies et al., Citation2018). The present study aimed to address these limitations by conducting a systematic review of studies that have investigated the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality in adults and investigated the effects of death anxiety treatments on the capability for suicide and suicidality in adults. That is, the study aimed to address the following research questions:

Is there a relationship between death anxiety and suicidality?

What are the impacts of death anxiety interventions on the capability for suicide and suicidality?

Method

Search strategy

A systematic search was conducted and reported according to the guidelines outlined in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist (Page et al., Citation2021). The protocol for the present study was prospectively registered with PROSPERO on 7th April 2022 [CRD42022301148]. To identify studies for possible inclusion, a systematic search of the electronic databases MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PubMed, and Web of Science was conducted from the earliest to July 29th, 2022. To examine the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality, the search strategy considered all aspects of suicide (e.g., suicide risk, suicidal ideation, suicidal behavior, suicide attempt/history). Databases were searched using a combination of keywords relating to death anxiety (death anxi* OR thanatophobia OR fear* of death OR fear* about death OR dying anxi* OR death attitudes OR death anxiety) intersected with capability for suicide (acquired capability OR nonsuicidal self-injury OR non-suicidal self-injury OR capability for suicide OR interpersonal theory of suicide OR IPT OR self-injurious behavior) and suicidality (suicidality OR suicide* OR attempted suicide). The search terms used Boolean operators of “AND” were searched using all fields, keywords, and DE Subjects (exact) headings. No limitations were placed on the search results.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

To be eligible for inclusion, participants must have been over 18 years; death anxiety and suicidality scores must have been obtained from the validated measure of these constructs; if the study included an intervention, the intervention must have specifically targeted death anxiety; and articles must have been in English. The criteria for exclusion were studies with child or adolescent populations; dissertations, abstracts, and conference presentations; and articles not in the English language.

Selection of studies and selection process

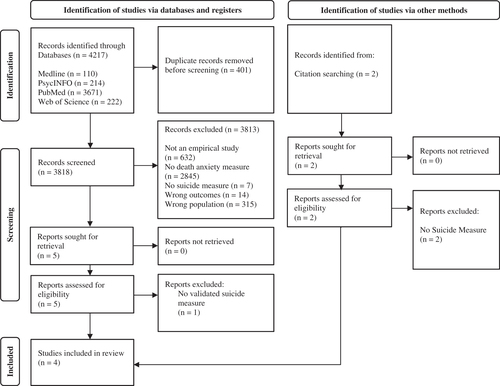

Overall, the search yielded 4219 studies, of which 401 duplicates were removed. Two independent reviewers (MS and RGM) screened the titles and abstracts for the remaining 3818 studies to determine their relevance for inclusion, with substantial inter-rater reliability (Kappa = .67). Primary sources of disagreement centered on distinctions between death anxiety and fearlessness of death constructs, with disagreements settled by consensus. Manual searches of reference lists of relevant studies were conducted to identify further eligible studies. A total of 3813 papers were excluded based on the title and abstract screening as they were not considered to be an empirical study relating to the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality, or the effects of death anxiety interventions on the capability for suicide.

Following this, two independent reviewers (MS and RGM) reviewed the full-text manuscripts of the remaining studies to assess eligibility for inclusion more comprehensively. Disagreements were settled by consensus. One article was excluded due to not having used a validated measure of suicide (Hoelter, Citation1979). This left a total of 4 studies that were analyzed in the systematic review. outlines the process of study inclusion.

Appraisal of quality

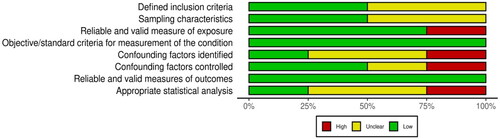

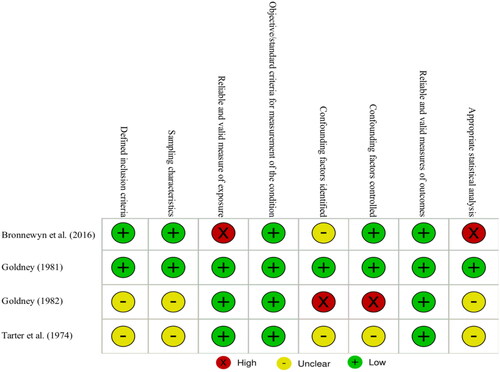

Assessment of the methodological quality of the included studies was conducted by two authors independently (MS and REM) using the 8-item Joanna Briggs Institute Checklist for Analytical Cross-Sectional Studies (Moola et al., Citation2017). This appraisal tool considers the methodological quality of a study and determines the extent to which the possibility of risk of bias (ROB) across the studies design, conduct, and analysis was addressed (Moola et al., Citation2017). Criteria included bias arising from selection, exposure, and outcome measures, confounding variables, and analysis type. Across each criterion, each study was graded “high”, “unclear”, or “low”. Substantial inter-rater reliability was obtained (Kappa = 0.78) and disagreements were settled by consensus. Of the four included studies, only one study was coded as having a low risk of bias across all domains. The detailed results of this risk of bias analysis can be found in and .

Results

Participant group

Among the 4 studies, the sample size varied between 50 participants and 113, with a mean sample size of 94 (SD = 25.66, N total = 376). The mean age of participants ranged between 22.40 and 73.61 years, and the mean age across the studies was 29.84 years (SD = 14.91). The percentage of females across the studies was 75.94% (SD = 26.91).

All of the studies utilized inpatient samples. Three consisted of participants following a recent suicide attempt (Goldney, Citation1981, Citation1982; Tarter et al., Citation1974), and one did not include suicide ideation or suicide history information (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2016). Two studies used the same participant group (Goldney, Citation1981, Citation1982), although one of these studies had a control comparison group (Goldney, Citation1982). One study included participants with somatic disorders and psychiatric symptoms, however, disorder-specific information was omitted (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2016). Another included participants with diagnoses of “neurotic depression” (65.45%), schizophrenia (7.27%), schizoaffective disorder (5.45%), and anorexia nervosa (1.82%) (Goldney, Citation1981). The detailed characteristics and results of the included studies can be found in .

Table 1. Characteristics of studies included in the review with death anxiety and suicide related outcome measures.

Study descriptions

The mean time since the study publication was 43 years (SD = 3.56). Overall, two studies reported the method of suicide attempt among participants (e.g., overdose; Goldney, Citation1981, Citation1982). Consistent with much of the literature, 100% of the studies used a cross-sectional design. One study examined participant’s death anxiety, risk of self-destruction, and potential for rescue following a recent suicide attempt (Tarter et al., Citation1974). One study examined participant’s death anxiety and correlates of lethality following a recent suicide attempt (Goldney, Citation1981). In a subsequent study, the death anxiety scores from the prior sample were compared to a non-suicidal control group on measures of self-reported attempt scores, correlates of lethality scores, and circumstances of the suicide attempt (defined as e.g., isolation, precautions against discovery/intervention, suicide note, preparation for the attempt, help-seeking following attempt) (Goldney, Citation1982). One study examined the relationship between death anxiety and a wish to die (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2016).

All studies used a self-report measure of death anxiety. Three studies administered the Templer (Citation1970) unidimensional 15-item Death Anxiety Scale (DAS) (Goldney, Citation1981, Citation1982; Tarter et al., Citation1974), whereas the fourth study used the Multidimensional Death Attitudes Profiles-R (Wong et al., Citation1994). Across the studies, three differing measures of suicidality were used. The two studies by Goldney (Citation1981, Citation1982) used the 15-item interview-administered and self-report Suicidal Intent Scale (Beck et al., Citation1974). However, only Goldney (Citation1982) reported findings on circumstances of the suicide attempt and self-reported attempt scores. As a measure of lethality and suicide intent, Tarter et al. (Citation1974) used the interview-administered Risk-Rescue Scale (Weisman & Worden, Citation1972). As a measure of a wish to die, Bonnewyn et al. (Citation2016) used one item from the 21-item Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation (Beck et al., Citation1988) measuring the intensity of suicidal ideation as (1) I have no wish to die, (2) I have a moderate wish to die, and (3) I have a strong wish to die.

Across the three studies consisting of participants with a recent suicide attempt, two reported that death anxiety and suicidality measures were administered within with 48 hr, or between 5–7 days of hospital admission (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2016; Tarter et al., Citation1974).

Relationship between death anxiety and suicidality

Across three studies, an inverse relationship between death anxiety and factors of suicidality was observed. Bonnewyn et al. (Citation2016) found a significant, negative relationship between death anxiety and a wish to die. Among those with a recent suicide attempt, Goldney (Citation1981) observed a significant, although the weak negative correlation between death anxiety scores and suicide intent scores. Using the same suicide attempt group, Goldney (Citation1982) found a significant, although the weak, and negative correlation between the death anxiety and circumstances of the attempt, self-reported intent, and total intent scores.

Goldney (Citation1981) found no significant difference between death anxiety scores and high, moderate, and low suicide groups. Goldney (Citation1982) observed no significant difference between death anxiety scores of the suicide attempt group and controls. Tarter (Citation1974) similarly found no significant difference between the means of first and multiple suicide attempters death anxiety.

Across studies examining factors of lethality, Goldney (Citation1982) found no significant difference between death anxiety scores and high lethality, intermediate lethality, and low lethality suicide attempt groups. Similarly, Tarter (Citation1974) observed no significant relationship between death anxiety and lethality, and death anxiety and risk of lethality among those with a recent suicide attempt. Further, no significant difference was found between the first and multiple attempt groups lethality, and risk of lethality scores (Tarter, Citation1974).

There was a small and significant positive correlation between death anxiety and rescue potential (Tarter, Citation1974). There was no significant difference between death anxiety and potential for rescue between first and multiple suicide attempters (Tarter, Citation1974).

Impacts of death anxiety interventions on capability for suicide and suicidality

No studies were found that examined the impact of a death anxiety intervention on suicidality.

Discussion

The primary aim of the present study was to systematically examine the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality, and the impact of psychological treatments on death anxiety, capability for suicide, and suicidality in adults. This systematic review identified 4 studies that investigated the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality and found a significant, although weak, negative relationship between death anxiety and suicide intent, circumstances of the attempt, and a wish to die. There was no relationship between death anxiety and lethality or risk of the lethality of a suicide attempt. Although, results found death anxiety to be significantly, and positively related to rescue potential. While the review aimed to examine the impact of psychological treatments on death anxiety, capability for suicide, and suicidality, no studies were found to examine this relationship.

The lack of a significant finding between death anxiety and lethality appears consistent with broader research demonstrating low correlations between suicide intent and lethality among those who attempted suicide (Yang et al., Citation2022). In the present study, lethality was not related to death anxiety, indicating that one’s level of death anxiety is unrelated to the degree of threat to life from the suicide attempt method. However, the finding that suicide intent varied inversely with death anxiety may suggest that the lethality of an attempt is not indicative of the seriousness of an individual’s suicide intent, rather, that the outcome of the attempt may be influenced by available methods at the time of the attempt. Further, the positive relationship between death anxiety and rescue potential may suggest that whilst the lethality of such an attempt may not influence the method chosen when death anxiety is high and suicide intent low, individuals may place themselves in situations where the opportunity for rescue is high. Subsequently, when death anxiety is low and suicide intent is high, lethality may be unrelated, although individuals may place themselves in situations where the potential for rescue is low.

Caution is warranted however when interpreting these results. Given the findings of an inverse relationship between death anxiety and suicide intent, circumstances of the attempt, and a wish to die, it may be reasonable to hypothesize that higher death anxiety may lead to lower suicide intent and subsequently greater rescue potential. However, causal inferences cannot be drawn given the cross-sectional nature of the studies. Secondly, in the present study, the correlations were statistically small, with death anxiety scores accounting for less than 10% of the variance in suicide intent and the potential for rescue scores. One interpretation for this may be due to sampling methods within the included studies. Three of the included studies had participants who had made a recent suicide attempt (Goldney, Citation1981, Citation1982; Tarter et al., Citation1974). Another study included participants with comorbid somatic disorders (Bonnewyn et al., Citation2016). When considered through an IPTS lens suggesting it is the fearlessness of death (and habituation to pain) that is necessary for the transition to the suicide attempt, it is possible that death anxiety was no longer a factor for participants who had attempted suicide as they may have already developed a fearlessness of death and pain insensitivity. This, and previous findings suggesting that greater death anxiety was associated with greater endorsement of suicidality among those with no reported suicide history, may further provide some defining factors about the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality (D’Attilio & Campbell, Citation1990; Minear & Brush, Citation1981).

Overall, the finding that death anxiety was weakly related to suicide intent, as well as the lack of significant difference between the death anxiety scores of a suicide attempt group and control group (Goldney, Citation1982), may suggest that it is premature to conclude that individuals who report a fear of death will not make attempts on their life.

While two systematic reviews have examined the impacts of psychological interventions on death anxiety (total included studies = 17; Grossman et al., Citation2018; Menzies et al., Citation2018), no studies have examined the impacts of death anxiety interventions on suicidality. This highlights that despite decades of empirical suicidology and TMT research examining the impacts of death on human behavior, these two fields have remained largely independent of each other. While no apparent adverse findings have emerged from the death anxiety treatment literature, it remains imperative to establish the impacts of death anxiety interventions on aspects of suicidality, especially among individuals who may be at increased risk to a “desire to die” constructs and habituation to pain through existing self-harming behaviors.

The current body of evidence however is not without notable limitations. Given the small number of studies, and their publication dates (>20 years) it is unclear to what extent the current study’s findings are relevant and generalizable to contemporary death anxiety and suicidality research, and the wider population more broadly. Further, while TMT posits the development of death anxiety “buffers” are universal, many of these studies have been conducted in Western cultural settings, which is problematic as research suggests that death fears may differ along cultural lines (Ma-kellams & Blascovich, Citation2012). Thus, as the present reviews included studies used samples from Western populations, the present findings may be limited in their broader generalizability. Finally, the current study found that the methodological quality of three of the four included studies was of some concern; only one of four studies indicated a low risk of bias across all domains. Thus, the robustness of the results from the present study are unclear.

Conclusion, implications, and future research

Suicidality remains among the most prevalent, devastating, and potentially preventable major public health concerns worldwide. Despite major advancements in medical and psychological research, it is evident that continuing to understand the factors associated with the progression from suicide desire to suicide attempt is imperative. The suicidology literature proposes that a capability for suicide, consisting of a fearlessness of death and habituation to pain, is necessary for the transition from suicide desire to the suicide attempt. Preliminary death anxiety research similarly suggests that a relationship between death anxiety and suicidality may exist. While contemporary scholars suggest that death anxiety reduction treatments may be important interventions for clinical psychologists in dealing with a range of disorders, the impact of such treatments on the capability for suicide remain unclear.

To our knowledge, the present study was the first to systematically examine the relationship between death anxiety and suicidality. Our findings of the notable gap between the suicidology and death anxiety treatment research may serve as a basis for further examination of both the death anxiety treatment research and the risk assessment processes within death anxiety treatment. To begin to reconcile discrepancies in the literature, it is imperative that future research examine the impacts of death anxiety intervention on aspects of suicidality, as well as empirically establish death anxiety and fearlessness of death as individual constructs. The causal nature between death anxiety and suicidality must be similarly established through rigorous laboratory experiments, and established among those with and without a suicide attempt history.

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgement to the Graduate School of Health, The University of Technology Sydney, Sydney, Australia, for providing funding to publish as open access.

Disclosure statement

Melissa A. Sims, Rachel E. Menzies & Ross G. Menzies declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Beck, A. T., Schuyler, D., & Herman, J. (1974). Development of the suicide intent scales. In A. T. Beck, H. L. P. Resnick, & D. J. Lettieri (Eds.), Prediction of suicide (pp. 54–56). Charles Press.

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Ranieri, W. F. (1988). Scale for suicide ideation: Psychometric properties of a self-report version. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 499–505. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198807)44:4<499::AID-JCLP2270440404>3.0.CO;2-6

- Bonnewyn, A., Shah, A., Bruffaerts, R., & Demyttenaere, K. (2016). Are religiousness and death attitudes associated with the wish to die in older people? International Psychogeriatrics, 28(3), 397–404. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610215001192

- Burke, B. L., Martens, A., & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 155–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309352321

- Cai, W., Tang, Y.-L., Wu, S., & Li, H. (2017). Scale of death anxiety (SDA): Development and validation. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 858–858. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00858

- Castano, E., Leidner, B., Bonacossa, A., Nikkah, J., Perrulli, R., Spencer, B., & Humphrey, N. (2011). Ideology, fear of death, and death anxiety. Political Psychology, 32(4), 601–621. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9221.2011.00822.x

- Chu, C., Buchman-Schmitt, J. M., Stanley, I. H., Hom, M. A., Tucker, R. P., Hagan, C. R., Rogers, M. L., Podlogar, M. C., Chiurliza, B., Ringer, F. B., Michaels, M. S., Patros, C. H. G., & Joiner, T. E. (2017). The interpersonal theory of suicide: A systematic review and meta-analysis of a decade of cross-national research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(12), 1313–1345. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000123

- D’Attilio, J. P., & Campbell, B. (1990). Relationship between death anxiety and suicide potential in an adolescent population. Psychological Reports, 67(3), 975–978. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1990.67.3.975

- Daniel-Watanabe, L., & Fletcher, P. C. (2022). Are fear and anxiety truly distinct? Biological Psychiatry Global Open Science, 2(4), 341–349. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsgos.2021.09.006

- Dickstein, L. S. (1972). Death concern: Measurement and correlates. Psychological Reports, 30(2), 563–571. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1972.30.2.563

- Franklin, J. C., Ribeiro, J. D., Fox, K. R., Bentley, K. H., Kleiman, E. M., Huang, X., Musacchio, K. M., Jaroszewski, A. C., Chang, B. P., & Nock, M. K. (2017). Risk factors for suicidal thoughts and behaviors: A meta-analysis of 50 years of research. Psychological Bulletin, 143(2), 187–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000084

- Furer, P., Walker, J. R., & Stein, M. B. (2007). Treating health anxiety and fear of death a practitioner’s guide. Springer-Verlag.

- Goldney, R. D. (1982). Attempted suicide and death anxiety. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 43(4), 159.

- Goldney, R. D. (1981). Attempted suicide in young women: Correlates of lethality. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 139(5), 382–390. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.139.5.382

- Greenberg, J. (2012). Terror management theory: From genesis to revelations. In P. R. Shaver, & M. Mikulincer (Eds.), Meaning, mortality, and choice: The social psychology of existential concerns (pp. 17–35). American Psychological Association.

- Grossman, C. H., Brooker, J., Michael, N., & Kissane, D. (2018). Death anxiety interventions in patients with advanced cancer: A systematic review. Palliative Medicine, 32(1), 172–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216317722123

- Hoelter, J. W. (1979). Religiosity, fear of death and suicide acceptability. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 9(3), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.1979.tb00561.x

- Iverach, L., Menzies, R. G., & Menzies, R. E. (2014). Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.09.002

- Joiner. (2005). Why people die by suicide. Harvard University Press.

- Juhl, J., & Routledge, C. (2016). Putting the terror in terror management theory: Evidence that the awareness of death does cause anxiety and undermine psychological well-being. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 25(2), 99–103. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721415625218

- Lehto, R. H., & Stein, K. F. (2009). Death Anxiety: An Analysis of an Evolving Concept. Research and Theory for Nursing Practice, 23(1), 23–41. https://doi.org/10.1891/1541-6577.23.1.23

- Lester, D. (1967). Fear of death of suicidal persons. Psychological Reports, 20(3 Suppl), 1077–1078. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1967.20.3c.1077

- Ma, J., Batterham, P. J., Calear, A. L., & Han, J. (2016). A systematic review of the predictions of the interpersonal–psychological theory of suicidal behavior. Clinical Psychology Review, 46, 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.04.008

- Ma-Kellams, C., & Blascovich, J. (2012). Enjoying life in the face of death: East―West differences in responses to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 103(5), 773–786. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029366

- Menzies, R. E., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2017). Death anxiety and its relationship with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(4), 367–377. https://doi.org/10.1037/abn0000263

- Menzies, R. E., Sharpe, L., & Dar‐Nimrod, I. (2019). The relationship between death anxiety and severity of mental illnesses. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 58(4), 452–467. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12229

- Menzies, R. E., Zuccala, M., Sharpe, L., & Dar-Nimrod, I. (2018). The effects of psychosocial interventions on death anxiety: A meta-analysis and systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 59, 64–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.09.004

- Minear, J. D., & Brush, L. R. (1981). The correlations of attitudes toward suicide with death anxiety, religiosity, and personal closeness to suicide. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 11(4), 317–324. https://doi.org/10.2190/YP62-4U57-V8CJ-XYNH

- Moola, S., Munn, Z., Tufanaru, C., Aromataris, E., Sears, K., Sfetcu, R., Currie, M., Qureshi, R., Mattis, P., Lisy, K., & Mu, P. F. (2017). Systematic reviews of etiology and risk. In: E. Aromataris, & Z. Munn, (Eds.), Joanna Briggs Institute reviewer’s manual. The Joanna Briggs Institute. https://reviewersmanual.joannabriggs.org/

- Noyes, R., Stuart, S., Longley, S. L., Langbehn, D. R., & Happel, R. L. (2002). Hypochondriasis and fear of death. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 190(8), 503–509. https://doi.org/10.1097/00005053-200208000-00002

- Orbach, I., Kedem, P., Gorchover, O., Apter, A., & Tyano, S. (1993). Fears of death in suicidal and nonsuicidal adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(4), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.4.553

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Ribeiro, J. D., Witte, T. K., Van Orden, K. A., Selby, E. A., Gordon, K. H., Bender, T. W., & Joiner, T. E. (2014). Fearlessness about death: The psychometric properties and construct validity of the revision to the acquired capability for suicide scale. Psychological Assessment, 26(1), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034858

- Saleem, T., Gul, S., & Saleem, S. (2015). Death anxiety scale: Translation and validation in patients with cardiovascular disease. The Professional Medical Journal, 22(6), 723–732. https://doi.org/10.29309/TPMJ/2015.22.06.1239

- Scocco, P., Marietta, P., Tonietto, M., Dello Buono, M., & De Leo, D. (2000). The role of psychopathology and suicidal intention in predicting suicide risk: A longitudinal study. Psychopathology, 33(3), 143–150. https://doi.org/10.1159/000029136

- Smith, P. N., & Cukrowicz, K. C. (2010). Capable of suicide: A functional model of the acquired capability component of the interpersonal-psychological theory of suicide. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(3), 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.3.266

- Spitzer, E. G., Zuromski, K. L., Davis, M. T., Witte, T. K., & Weathers, F. (2018). Posttraumatic stress disorder symptom clusters and acquired capability for suicide: A re-examination using DSM‐5 criteria. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 48(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12341

- Stiluon, J. M., McDowell, E. E., & Shamblin, J. B. (1984). The suicide attitude vignette experience: A method for measuring adolescent attitudes toward suicide. Death Education, 8, 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481188408252489

- Strachan, E., Schimel, J., Arndt, J., Williams, T., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Greenberg, J. (2007). Terror mismanagement: Evidence that mortality salience exacerbates phobic and compulsive behaviours. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 33(8), 1137–1151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167207303018

- Tarter, R. E., Templer, D. I., & Perley, R. L. (1974). Death anxiety in suicide attempters. Psychological Reports, 34(3), 895–897. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1974.34.3.895

- Templer, D. I. (1970). The construction and validation of a death anxiety scale. The Journal of General Psychology, 82(2d Half), 165–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.1970.9920634

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

- Velkoff, E. A., & Smith, A. R. (2019). Examining patterns of change in the acquired capability for suicide among eating disorder patients. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 49(4), 1032–1043. https://doi.org/10.1111/sltb.12505

- Weisman, A. D., & Worden, J. W. (1972). Risk-rescue rating in suicide assessment. Archives of General Psychiatry, 26(6), 553–560. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1972.01750240065010

- Wong, P. T. P., Reker, G. F., & Gesser, G. (1994). Death attitudes profile-revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. In R. A. Neimeyer (Ed.), Death anxiety handbook: Research, instrumentation, and application (pp. 121–148). Taylor & Francis.

- World Health Organization. (2018). National suicide prevention strategies: Progress, examples, and indicators. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/279765.

- Yang, H. J., Jung, Y. E., Park, J. H., & Kim, M. D. (2022). The moderating effects of accurate expectations of lethality in the relationships between suicide intent and medical lethality on suicide attempts. Clinical Psychopharmacology and Neuroscience, 20(1), 180–184. https://doi.org/10.9758/cpn.2022.20.1.180

- Zuccala, M., Menzies, R. E., Hunt, C. J., & Abbott, M. J. (2022). A systematic review of the psychometric properties of death anxiety self-report measures. Death Studies, 46(2), 257–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1699203