Abstract

Personal grief takes place in a social context, such as the family setting. This study aimed to understand how Namibian caregivers and children/adolescents communicate parental loss, in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. An ethnographic design was used, in which 38 children, adolescents, and their caregivers were interviewed. The results show that caregivers shared few memories and provided minimal information about the deceased parents. However, the majority of adolescents and children wished for information. A relational Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver model was used to map the reasons for this silence. This model is useful for grief interventions that aim to strengthen communication.

Introduction

Grief is a common human reaction to loss and comprises psychological, social, and cultural processes. While research on grief has been increasing over the last decades, the focus has been mainly on adults or “average” populations. Meanwhile, research on how children experience grief and loss has been largely neglected; especially qualitative studies exploring children’s bereavement experiences, and studies in non-Western settings are limited. When a child loses one or both parents, they are not only dealing with the loss of a loved one, but children often also deal with the loss of a guide and important role model in their lives. Furthermore, the death circumstances play an important role in how one deals with grief and loss.

In this research, we want to study how children in northern Namibia communicate parental loss with caregivers in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. In Southern Africa, the HIV/AIDS pandemic is the most severe. Namibia has a generalized HIV epidemic, with 8.45 percent of the general population living with HIV (U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), Citation2022). Since 2005, rates of AIDS-related deaths have dropped significantly due to ART rollout (UNAIDS, Citation2020), however, HIV/AIDS is still the leading cause of death in Namibia (Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), Citation2020). Many young people are bereaved by one or both parents. Of all Namibian children aged 18 years and below, 11.1 percent lost at least one parent, with 1.4 percent having lost both parents (Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), Citation2017). Orphans in Namibia are mainly taken care of by the extended family. On average, 14 percent of households in Namibia care for orphans who are 18 years or younger (Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA), Citation2017).

There is a dearth of research that focuses on grief communication from the perspective of the young bereaved individual (Cohen & Samp, Citation2018). Family communication about AIDS-related death in southern African settings is often surrounded by silence and secrecy (Wood et al., Citation2006). In Zimbabwe, adults – the sick parent or caregivers following parental loss – do not inform adolescents about parental illness and death (Wood et al., Citation2006). In parts of South Africa, death is not talked about openly with children, nor were memories of the deceased elicited by adults (Van der Heijden & Swartz, Citation2010). In Uganda, orphaned children similarly received little information about the illness and death of their deceased parents (Daniel et al., Citation2007).

However, research from North American and European countries reveals a central role of communication within families in the grieving process (Bosticco & Thomson, Citation2005). Neimeyer (Citation1999) stated that a major loss has implications for the bereaved individual’s sense of identity. Such loss can undermine the coherence of the self-narrative (Neimeyer et al., Citation2010). Sharing stories about the deceased and the loss helps individuals to repair their sense of identity and reassert their understanding of roles within the family (Neimeyer, Citation2001; Walter, Citation1996). While these theoretical perspectives offer insight into the grieving processes of adults, the question remains about how children and adolescents, who are still in the development of a narrative identity, are dealing with grief and loss. It also raises the question of whether these grieving processes take place in a similar way in an African context. For instance, in Malawi, children are encouraged to forget about their parents and acknowledge their new carers as their parents, as part of a social process through which psychological, economic, and social recovery takes place (Hutchinson, Citation2011).

Previous research has revealed that attentive and sensitive parenting communication is associated with less psychopathology following death (Howell et al., Citation2016; Shapiro et al., Citation2014; Weber et al., Citation2021). This means that being able to communicate openly about parental death helps children to cope with death (Raveis et al., Citation1999). While limited research is available on this topic in African contexts, there is evidence of similar findings. In South Africa, caregiver-child communication in contexts of disadvantage and adversity was found to have a protective role; more frequent conversations with caregivers about personal problems and challenges could be responsible for orphan's (and non-orphans) lower anxiety and depression scores (Govender, et al., Citation2014).

An overarching theme from these studies is the importance of openness in communication about the parents’ death; however, we also know from previous research that secrecy is one issue surrounding AIDS-related death. Therefore, in this explorative research, we want to investigate how caregiver and children/adolescent communication takes place in this particular grieving context. The research question is: What information about the late parent is desired by children and adolescents and provided to them by caregivers?

Methods

This study is part of a larger research project focusing on orphaned and non-orphaned children and adolescents in northern Namibia. The research design consisted of an ethnographic field study of 18 months in north-central Namibia. The study was mainly carried out in a rural village, consisting of widely spaced homesteads often inhabited by extended families, among Oshiwambo-speaking people. In this region, parentally bereaved children are generally taken care of by maternal relatives.

Procedure and participants

The study included parentally bereaved participants and their caregivers. Purposeful sampling with a random element was used to identify and select information-rich cases (Patton, Citation2002). Ten parentally bereaved children (6 boys and 4 girls) aged 9-–12 years were selected randomly from the Orphans and Vulnerable Children (OVC) registration list provided by the primary school in the village. One girl from the non-orphan group of the larger research project was added as during the research it turned out her father had died some years ago. Eleven parentally bereaved adolescents (3 male, and 8 female) aged 18–21 years participated as well. The adolescents were part of follow-up research and were seven years earlier selected by their teachers as OVC registration lists were not available at that time. Additionally, 11 caregivers of the child group and 6 caregivers of the adolescent group participated (see ). Although the study took place in a region heavily affected by HIV/AIDS, AIDS as the cause of death was not a recruiting criterion, so as not to exclude families where the parent’s cause of death is shrouded in silence. During the study, it turned out that approximately a third of all deaths were HIV related, although more caregivers hinted during interviews that the deceased parent may have been HIV positive. Other causes of death included suicide, but usually, the cause of death remained unclear due to conflicting explanations or because caregivers did not know the cause of death.

Table 1. Characteristics of the child and adolescent participants (N = 38).

Data collection and analysis

The larger research project consisted of various data collection methods including individual interviews, expert interviews, home visits, and participant observation. As the children were not used to voicing their opinion and due to the sensitivity of the research subject, an afterschool Kids Club was started. During these meetings, focus groups, visual techniques, and writing exercises were employed. Meeting with the children over a long period provided the opportunity to build confidence and trust. Furthermore, the themes of the Kids Club were carefully designed, with sensitive topics only discussed when sufficient trust had been built. The present study draws on 3 focus groups with the child group, several semi-structured interviews with children, adolescents, and caregivers, and an interview with an NGO worker. The interviews took place after school time at the primary school with the children, at a secondary school or in the fields with the adolescents, and with caregivers in their homes. The interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim by the first and the third author.

The transcripts were analyzed by the first author on the basis of inductive content analysis which is used when the researched phenomenon is not dealt with in other studies (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008). The transcripts were read in their entirety, then coded and categorized in broader themes using NVivo. At regular stages, during data collection and analysis the findings were discussed with the third author.

Ethical considerations

Research permission was obtained from the Namibian Ministry of Education; ethical approval was granted by the ethical review board of the Vrije Universiteit University Amsterdam. Informed written consent was given by the children and adolescents and their caregivers on behalf of themselves and the child in their care. A meeting with the caregivers was organized to inform them about the features of the research, that participation was voluntary, that they had the right to withdraw and that they were guaranteed confidentiality before consent was sought. Reflexivity in seeking informed consent from children is needed, as due to adult-child power disparity in relation to the researcher children may feel reluctant to refuse or withdraw from participation. It might also be challenging for children to understand what participation in the study entails. In this study, consent was seen as a process whereby children were given multiple opportunities to opt out throughout the research. Furthermore, when consent is sought attention should be paid to how long after the death of a loved one the study is undertaken (Cook, Citation1995). The parent(s) of most child and adolescent participants died at least a year ago, with most of them several years ago. One paternal orphan lost his mother in between two fieldwork visits and was interviewed some months after her death.

As this study dealt with parental loss and a stigmatized disease (HIV/AIDS), a generally careful approach to the study was employed. Consultations took place with local health workers: staff from NGOs working with HIV-affected children in the region, a social worker, and a psychologist. Furthermore, the third author has worked as a counselor for adolescents in the region and could draw on personal experiences because she herself lost both her parents as a child. At the end of the study, all children and adolescents evaluated their overall participation positively; it gave them a chance to talk about their loss and they shared that they felt they were being listened to. Adolescents perceived sharing their stories in the focus groups as encouraging as they could give each other advice. The adolescents also hoped their participation would raise awareness about their situation. One commented, “When people read about me, they are going to learn about children that have lost their parents.”

Results

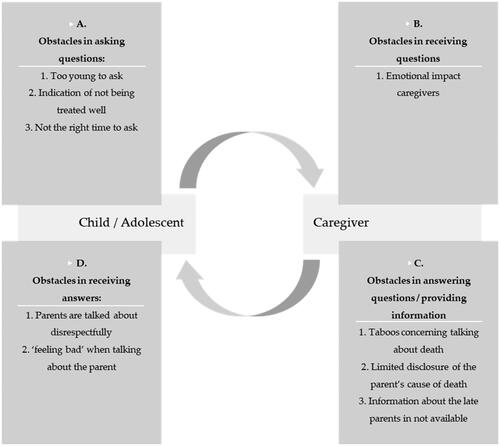

The results are presented in two steps, first, the focus is on more general aspects of limited child-caregiver communication on parental loss, and in the second, obstacles are mentioned that underlie this limited communication. Key themes that were identified during the analysis were memory sharing, information about the parent, and information about the parent’s cause of death. The analysis further showed that the late parents were hardly discussed within the households. Therefore, within the key themes, different obstacles were listed that limited caregiver-child communication. A relational Sender-Message-Channel-Receiver (SMCR) model was used to map these obstacles (see ). The SMCR model of communication (Berlo, Citation1960) shows the elements of a communication process. Scholars have suggested adapting the SMCR model by making it relational: the receiver provides feedback to the sender. This relational SMCR model will be discussed below in relation to the data.

Limited caregiver-child communication on parental loss

In general, caregivers provided minimal information about the deceased parents and shared few memories about them with the children or adolescents in their care. Only a few caregivers spoke about the deceased parents; shows the type of memories and information they shared. These caregivers felt this was important as the deceased parent had ‘left memories behind’ or that through the HIV/AIDS epidemic, many children did not know their parents. Largely, the parents’ cause of death was not disclosed. More than half of the child and adolescent respondents said they received no information about what caused their parent’s death or were only told they died of a disease. A few children and adolescents were informed that their parent had died of AIDS. Others mentioned various other causes of death, but this was often not confirmed by their caregivers.

Table 2. Provided and desired information about the deceased parents.

However, most of the adolescents and half of the child group desired information and wished to hear memories about the deceased parents (see ). Those who did not know their parent because the parent had died when they were young, or because the father had not been present in their mother’s life, were generally eager to hear about the parent’s behavior, character, and life circumstances. A female, double orphaned adolescent reported that receiving information about the late parent was important to understand her own behavior: “Sometimes a child can behave in a certain way and it is how the father or mother was behaving.” Especially adolescents wished to know what caused their parent’s death, and some of them felt that the truth was withheld from them. For instance, a male adolescent lost both his parents when he was young. He remembered that they had been sick before they died. He wished to be informed about their cause of death, but relatives only told him that a serious disease caused their deathFootnote1. He stated, “I have this feeling that they know, but cannot tell me.”

Yet, several child participants did not desire information about their late parents as it would make them sad, or they felt they had received enough information. A few adolescents did not have a need for information as the late father had been absent in their lives before their death. A female, paternal orphaned adolescent reported, “It does not help anything, even if I have information about him, I do not know him.”

Obstacles in caregiver-child communication on parental loss

Several reasons for this limited communication were identified. gives an overview of how the different difficulties may relate to each other. The themes of this model are not mutually exclusive but are presented as separate categories for the sake of clarity. Four categories of obstacles are: obstacles perceived by children and adolescents in asking questions to the caregivers; problems that caregivers experience in receiving questions; reasons for caregivers to not provide children and adolescents with information or answer their questions; and difficulties from children and adolescents with receiving information about their deceased parents. The various facets of these four obstacles are discussed below.

Children and adolescents: Obstacles in asking questions

Children were considered too young to understand or deal with death-related issues, and questions about their late parents were perceived as inappropriate, unnecessary, or the child was considered to have received enough information. The grandmother of a male paternal orphaned child related, “I think for those who have pictures – pictures are enough to show a child how the late parent looked like. I do not see it necessary to tell a child stories about the late parent.” Caregivers were also afraid that asking questions could lead to further questions, which they felt uncomfortable answering. If children asked questions, they would be told to keep quiet, or their questions were ignored by caregivers, as a great-aunt who took care of a paternal orphaned child reported, “Children should not ask a lot about their late parents. If a child asks you once, you pretend to be busy the next time he asks, to stop him bothering you with questions.”

Children and adolescents therefore generally did not ask questions about their late parents. They mentioned they could start asking questions about their parents when they were older, from ages 18-21 years onwards. Nevertheless, several participants who had reached this age were still not informed, especially not about their parents’ cause of death. A male, double orphaned adolescent expressed his frustration about still not receiving this information, stating, “I want to know now. It is my mother and not just somebody.”

Children avoided asking about their parents in foster households because it could disturb their caregiver; it would indicate that a child was unhappy in the household or not treated well by its foster caregivers. This was confirmed by the caregiver respondents. Other children mentioned “not feeling free” to ask questions due to a lack of familiarity with their caregivers. A girl who lived with her aunt and uncle expressed that due to these reasons writing a letter to her deceased father would not be accepted in her foster household:

I always think of writing a letter to my father, but people at my house like to search other people's bags. If I write it and put it in my bag, and if they find it, the house will become too small for me because they would be angry at me. Not only would they be angry, but I would also be beaten, not only that, but they would also be complaining endlessly, and I would not be allowed to eat. (Female child, paternal orphan)

Caregivers: Obstacles in receiving questions

Surviving parents and grandparents mentioned that questions from children about their deceased parents confronted them with the loss, it would hurt them, and it reminded them that the child had to grow up without the parent. The surviving mother of a male child participant reported, “If a child starts to ask you, these are heart-moving questions, because I would not be in a situation where I am now. It is always on my mind that he left me alone with many children.” To avoid this emotional burden, a child should not talk or ask about the late parent and was often prevented from talking. Children and adolescents confirmed this. For instance, a male, paternal orphaned adolescent explained that he had many questions about his late father but that he could not ask them: “My mother does not like that part. She says it brings her bad memories.”

Caregivers: Obstacles in answering questions and providing information

Although deceased people were remembered, talking about death was inappropriate and may be considered taboo among Oshiwambo-speaking people. An NGO worker explained:

It is like a taboo; you do not talk about things before they happen. If you talk about it, you want it to happen to you, which means you want misfortune to come your way. It is like cursing yourself.

Caregivers listed several reasons for limited disclosure. Firstly, in the past, Oshiwambo-speaking people almost never spoke about the sickness which led to the death of a parent, and even today it was considered “difficult” or “unnecessary” to inform children about it. Secondly, some caregivers who were not closely related to the child in their care, such as a great-aunt or a child’s grandmother’s cousin, felt that disclosure of the late parent’s cause of death was the responsibility of closely related relatives. Thirdly, in case the parent had died of AIDS, negative consequences of HIV disclosure were mentioned. HIV-related stigma and shame were important reasons for the non-disclosure of the late parent’s HIV infection, or delayed disclosure when children had reached adulthood. Caregivers were concerned that children would not be able to keep the diagnosis secret and that the parent was talked about negatively. Furthermore, caregivers feared that children might be bullied when the late parent’s HIV infection became known. A male, paternal orphaned adolescent, therefore, felt that the HIV/AIDS diagnosis should be kept a secret for children:

HIV is embarrassing; children should not be told about that. Sometimes children would be asked: “What caused the death of your parents?” The child says: “HIV/AIDS.” Others are listening and from there, they would be shouting at each other: “Your mother died of HIV/AIDS.” (Male adolescent, paternal orphan)

They are only told that their father passed away but are not told the specific illness the father was suffering from. When they have grown up, they should be told: your father died this kind of death, so if you are not behaving you will die. If I tell them when they are young, they might be scared or shocked because some circumstances surrounding the cause of death are shocking. The child may think; I might be carrying the disease my father had. (Great-aunt, caregiver of female paternal orphaned adolescent)

Caregivers could often not provide the child with information or answer questions about the life circumstances of the parent, as they simply lacked such information. This was especially the case when a child stayed with distant relatives or when the late father had not been present in the child’s life before his death. For instance, a great-aunt, the caregiver of a male paternal orphaned boy expressed, “I do not know anything about his father so I really cannot tell him about his father.”

Children and adolescents: Obstacles in receiving answers

In some cases, household members spoke disrespectfully about the late parent in front of the child or adolescent, which made them “feel bad.” A female adolescent related that her mother’s behavior was talked about negatively in her foster household, the household of her great-aunt:

If your mother did not behave well, and she did bad things, and the story would be told in front of everyone, and other children would make fun of me about what my mother used to do, then it is not good that they talk about my mother. And these children would say their mothers do not do things like that. (Female adolescent, maternal orphan)

Even though many children wished for information about their deceased parents, at the same time, it made them unhappy when they were discussed in the household. It reminded them about their loss, and they feared talking about death: “I do not like a dead person to be spoken about.” Some adolescents felt that receiving information about their late parents even increased their sadness. For instance, an adolescent had always wished for information about her father. However, after she had received a picture of him, and was told about his personality and living circumstances, she realized that it had increased her sense of loss:

It is not good to know things because you will think about your father, and you will cry often, which is not good. Even when I am busy with something and start - thinking about my father I start to cry; because I do not know him, but others know their father. (Female adolescent, paternal orphan)

Discussion

Our goal was to enhance understanding of how communication on parental loss takes place among caregivers and children/adolescents in the context of the HIV/AIDS epidemic in Namibia. The present study demonstrated that generally the deceased parent was hardly talked about, and little information was provided about the parent. For caregivers, it was almost self-evident not to raise the subject. Several children and adolescents refrained from discussing their late parents as well: it would protect them from sadness and worries, or they said they had enough information. However, the larger part of child and adolescent participants wished to form an image of their parent; get clarity about their cause of death and showed a need to talk about the loss suffered. It is therefore important to understand the reasons underlying this silence. Barlo (1960) points out in his SMCR model that communication between the sender and receiver is, amongst others, shaped by social systems and culture. This study showed indeed that various socio-cultural, but also practical and emotional factors prevented caregivers and children from talking about parental loss. These diverse factors are mapped in a relational SMCR model.

The obstacles presented in the model partly relate specifically to the Namibian and African cultural contexts and partly resemble global issues that are found in the general grief literature on how children are included in grieving traditions. For instance, the child obstacle ‘too young to ask’ relates to clear hierarchal relations between children and adults, and authoritarian and unidirectional parenting styles. Such parenting styles are also found in discussing HIV and sexuality in diverse sub-Saharan African countries (Bastien et al., Citation2011). Hierarchical relations underly the notion that children asking questions about sensitive topics would demonstrate a lack of respect (Denis, Citation2009). In the present study, caregivers stop children from asking questions as they fear their own emotional distress. American parents who have lost a child similarly often wish to “spare” themselves and the remaining children the emotional burden of retelling the story (DeMaso et al., Citation1997, p.1299).

The study showed that the topic of parental death, and particularly HIV-related death, is taboo. Similar taboos are found in South Africa, such as speaking about death in general (Mdleleni- et al., Citation2004), and talking to children about death (Van der Heijden & Swartz, Citation2010). A low rate of informing orphans about AIDS as the parental cause of death is in accordance with a low HIV disclosure rate of parents to their children worldwide (Qiao et al., Citation2013), and the reasons for nondisclosure mentioned in this study resemble motives mentioned in the global literature (Schrimshaw & Siegel, Citation2002, Thomas et al., Citation2009).

Other factors that hindered caregiver-child communication are rooted in patterns of child fosterage. Madhavan (Citation2004) argues that attention to child fosterage is pivotal in understanding orphans’ circumstances, particularly in the context of the HIV epidemic. Such patterns influenced and obstructed caregiver-child communication in various ways. For instance, children feared that caregivers would interpret questions about their parents as criticism of the way they treated orphans in their care, and children often could not find ‘the right time’ to ask their remaining parent about their deceased parent when this parent sporadically visited them in their foster families. Besides, caregivers often could not provide information about the late parent as they simply had not known the parent, for instance as the child was fostered by distant relatives. Furthermore, children were hurt when their deceased parent was spoken about negatively in the foster family.

How do these findings relate to grief theories, which have been mainly developed by Northern American and European scholars? The children’s and adolescents’ wish to form an accurate picture of their parents, and their parent’s life seemed to be related to identity issues. This offers support for the argumentation of Neimeyer (Citation1999) that loss may impact one’s sense of self. Besides, the Dual Process model of coping with bereavement (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1998) appears useful to shed light on the emphasis on silence in dealing with loss in northern Namibia. A premise of this model is the occurrence of diverse types of coping within different cultures and individuals. In the here studied cultural context, not sharing memories and information is part of the cultural system. Besides, several caregivers and some children and adolescents opted for silence as this would protect them from feeling sad. This approach seems in line with the restoration-orientated approach in the Dual Process model. Thus, instead of confronting grief, other patterns of adjustment are applied. Grief is a multi-layered process that reveals various negative emotions, such as sadness, guilt, shame, and anger, but these emotions are very much intertwined within the broader grief culture. Understanding grief from various perspectives asks for more research in non-Western contexts to reveal the unique cultural sensitivities that underline this complex emotion. This study stresses the notion that grief is socially constructed and not ‘only’ taking place within the mind (Jakoby, Citation2012). Moreover, the study encourages more research into the grief of children to re-develop existing grief models from the perspective of younger populations. What are the implications of grief from a narrative perspective, when children are still in the development of a narrative identity? What unique cultural implications of narrative development apply to the here interviewed children and caregivers? More research, into the narrative and meaning-making development of children in relation to grief, should be considered.

There are several limitations to this study. The sample was relatively small which limits the validity of generalizations from the findings. Furthermore, the foster situation of the respondents was not homogenous. It differed in closeness to the caregiver (close versus distantly related relatives) and in family size (a few nuclear families versus large extended families) which likely affected the family communication on loss. In this study, we focused on obstacles in intergenerational communication. An exciting area for future research is to map strengths in caregiver-child communication within the model; this contributes to understanding resilience in dealing with parental loss.

Lastly, our findings suggest some directions for interventions. Since many adolescents and children wish to receive information and share memories about their late parents, it is important to consider how caregiver-child communication can be improved. Scholars argue that to design effective interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, there is a need to understand the role and function of intergenerational communication in different contexts (Vaz et al., Citation2010). For instance, in existing bereavement programs targeting this region, the positioning of caregivers tends to be overlooked (Wood et al., Citation2006). The present study might in two ways inform bereavement interventions that focus on assisting children and youth in dealing with parental loss in sub-Saharan African countries. Firstly, it presents a model of grief communication, which can help organizations that conduct bereavement interventions in understanding and strengthening caregiver-child communication. The model can be applied as a tool to map both obstacles and strengths on social, cultural, emotional, and practical levels. Although the model is used here in a Namibian context, it is essentially trans-cultural in nature. More specifically the model relates to cultures that share similar values in caregiver-child communication about sensitive topics, such as death, grief, and HIV. Cohen and Samp (Citation2018) argue that models of grief communication are rare, “which is problematic due to its salience in intrapersonal, interpersonal, and societal contexts” (p. 239). Secondly, the model focuses particularly on dyadic interactions. This focus gives insight into the dynamics between the position of the child/adolescent and the caregiver within intergenerational communication. Penner et al. (Citation2020) state that there is a need for a focus on dyadic relations in family interventions in sub-Saharan Africa. Penner et al. (Citation2020), in their review of studies that evaluated caregiver and family interventions to support OVC mental health, found that most of these interventions focused on the use of behavioral and cognitive strategies to improve caregiving behavior and parenting skills. They argue that instead of relying on the import of caregiver skills, a focus on naturally occurring dyadic interactions is more relevant in the context of OVC in sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion

In northern Namibia, as in other southern African settings, there is little openness in discussing the death of parents in a family setting, especially AIDS-related deaths. Openness in communication about the parent’s death seems to help children to cope with the loss, although this needs to be further examined in various cultural settings. In this study, the SMRC model helps to explain the ways in which caregivers and children/adolescents in their custody discuss and don’t discuss the death of the child’s parent(s) in Namibia. The reasons for being silent about the deceased parent are diverse and include amongst others hierarchal relations, taboos, protection against sadness, nondisclosure of the deceased parent’s HIV infection, and fosterage-related issues. By doing so, this study contributes to our understanding of grief communication from the perspective of the young bereaved individual.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the children, adolescents, and caregivers who participated in the interviews.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Caregivers often share the final cause of death of a HIV infected person which is written on the death certificate with the child, but keep the HIV/AIDS diagnosis secret.

References

- Bastien, S., Kajula, L. J., & Muhwezi, W. W. (2011). A review of studies of parent-child communication about sexuality and HIV/AIDS in sub-Saharan Africa. Reproductive Health, 8(25), 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-8-25

- Berlo, D. (1960). The process of communication. Rinehart, & Winston.

- Bosticco, C., & Thompson, T. (2005). The role of communication and storytelling in the family grieving system. Journal of Family Communication, 5(4), 255–278. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327698jfc0504_2

- Cohen, H., & Samp, J. A. (2018). Grief communication: Exploring disclosure and avoidance across the developmental spectrum. Western Journal of Communication, 82(2), 238–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2017.1326622

- Cook, A. S. (1995). Ethical issues in bereavement research: An overview. Death Studies, 19(2), 103–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481189508252719

- Daniel, M., Malinga Apila, H., Bj Rgo, R., & Therese Lie, G. (2007). Breaching cultural silence: Enhancing resilience among Ugandan orphans. African Journal of AIDS Research, 6(2), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085900709490405

- DeMaso, D. R., Meyer, E. C., & Beasley, P. J. (1997). What do I say to my surviving children? Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 36(9), 1299–1302. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-199709000-00024

- Denis, P. (2009). Are Zulu children allowed to ask questions? Silence, death and memory in the time of AIDS. In B. Carton, J. Sithole, & J. Laband (Eds.), Being Zulu, Contested Identities Past and Present. (p. 1–14). Retrieved June 8, 2022 fromhttp://www.kznhass-history.net/files/seminars/Denis2003.pdf

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Govender, K., Reardon, C., Quinlan, T., & George, G. (2014). Children’s psychosocial wellbeing in the context of HIV/AIDS and poverty: A comparative investigation of orphaned and non-orphaned children living in South Africa. BMC Public Health, 14, 615. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-615

- Howell, K. H., Barret-Becker, E. P., Burnside, A. N., Wamser-Nanney, R., Layne, C. M., & Kaplow, J. B. (2016). Children facing parental cancer versus parental death: The buffering effects of positive parenting and emotional expression. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(1), 152–164. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0198-3

- Hutchinson, E. (2011). The psychological well-being of orphans in Malawi: “Forgetting” as a means of recovering from parental death. Vulnerable Children and Youth Studies, 6(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/17450128.2010.525672

- Jakoby, N. R. (2012). Grief as a social emotion: Theoretical perspectives. Death Studies, 36(8), 679–711. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.584013

- Joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). (2020). Namibia country factsheet 2020. Retrieved 2022, July 20 from https://www.unaids.org/en/regionscountries/countries/namibia

- Madhavan, S. (2004). Fosterage patterns in the age of AIDS: Continuity and change. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 58(7), 1443–1454. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00341-1

- Mdleleni-Bookholane, T., Schoeman, W., & Van der Merwe, I. (2004). The development in the understanding of death among black South African learners from the Eastern Cape, South Africa. Health SA Gesondheid, 9(4), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.4102/hsag.v9i4.176

- Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA). (2017). Namibia Inter-censal Demographic Survey 2016 Report. Namibia Statistics Agency, Windhoek

- Namibia Statistics Agency (NSA). (2020). Namibia Mortality and Causes of Death Statistics report, 2016 and 2017. Namibia Statistics Agency, Windhoek.

- Neimeyer, R. A. (2001). Reauthoring life narratives: grief theory as meaning reconstruction. Israel Journal of Psychiatry and Related Sciences, 38, 171–183.

- Neimeyer, R. A. (1999). Narrative strategies in grief therapy. Journal of Constructivist Psychology, 12(1), 65–85. https://doi.org/10.1080/107205399266226

- Neimeyer, R. A., Burke, L. A., Mackay, M. M., & Van Dyke Stringer, J. G. (2010). Grief therapy and the reconstruction of meaning: From principles to practice. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 40(2), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-009-9135-3

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods. (3th ed). Sage Publications, Inc.

- Penner, F., Sharp, C., Marais, L., Shohet, C., Givon, D., & Boivin, M. (2020). Community-based caregiver and family interventions to support the mental health of orphans and vulnerable children: Review and future directions. In M. Tan (Ed.), HIV and Childhood: Growing up Affected by HIV. New Directions for Child and Adolescent Development., 171, 77–105. https://doi.org/10.1002/cad.20352

- Qiao, S., Li, X., & Stanton, B. (2013). Disclosure of parental HIV infection to children: A systematic review of global literature. AIDS and Behavior, 17(1), 369–389. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-011-0069-x

- Raveis, V. H., Siegel, K., & Karus, D. (1999). Children’s psychological distress following the death of a parent. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 28(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021697230387

- Schrimshaw, E., & Siegel, K. (2002). HIV-infected mothers’ disclosure to their uninfected children: Rates, reasons, and reactions. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 19(1), 19–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407502191002

- Shapiro, D., Howell, K., & Kaplow, J. (2014). Associations among mother–child communication quality, childhood maladaptive grief, and depressive symptoms. Death Studies, 38(1-5), 172–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2012.738771

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1998). Culture and grief. Bereavement Care, 17(1), 7–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682629808657425

- Thomas, B., Nyamathi, A., & Swaminathan, S. (2009). Impact of HIV/AIDS on mothers in Southern India: A qualitative study. AIDS and Behavior, 13(5), 989–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-008-9478-x

- U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR). (2022). Namibia country operational plan 2022 Strategic Direction Summary. Retrieved 2022, December 18 from https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Namibia-COP22-SDS.pdf

- Van der Heijden, I., & Swartz, S. (2010). Bereavement, silence and culture within a peer-led HIV/AIDS prevention strategy for vulnerable children in South Africa. African Journal of AIDS Research, 9(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2010.484563

- Vaz, L. M. E., Eng, E., Maman, S., Tshikandu, T., & Behets, F. (2010). Telling children they have HIV: Lessons learned from findings of a qualitative study in Sub-Saharan Africa. AIDS Patient Care and STDs, 24(4), 247–256. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2009.0217

- Walter, T. (1996). A new model of grief: Bereavement and biography. Mortality, 1(1), 7–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685822

- Weber, M., Alvariza, A., Kreicbergs, U., & Sveen, J. (2021). Family communication and psychological health in children and adolescents following a parent’s death from cancer. Omega, 83(3), 630–648. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222819859965

- Wood, K., Chase, E., & Aggleton, P. (2006). ‘Telling the truth is the best thing’: Teenage orphans’ experiences of parental AIDS-related illness and bereavement in Zimbabwe. Social Science & Medicine, 63(7), 1923–1933. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.04.027