Abstract

Following bereavement, continuing bonds (CBs) include engaging with memories, illusions, sensory and quasi-sensory perceptions, hallucinations, communication, actions, and belief that evoke an inner relationship with the deceased. To date, the literature has been unable to confirm whether retaining, rather than relinquishing, bonds is helpful. A mixed studies systematic literature search explored how CBs affect grief. Studies on the effect or experience of CBs on adjustment following bereavement were eligible for inclusion. Six computerized databases were searched. A total of 79 of 319 screened studies were included. Three themes were derived from the thematic analysis: (1) comfort and distress, (2) ongoing bonds and relational identity, and (3) uncertainty, conceptualizing, and spirituality. Themes describe the role of CBs for the accommodation of the death story, transformation of the relationship, meaning reconstruction, identity processes, and affirmation of spiritual belief. Results shed light on the adaptive potentials for CBs.

Introduction

Continuing Bonds (CBs) are defined as an ongoing inner relationship with the deceased (Klass et al., Citation2014). CBs include attempts to keep memories alive through dialogue with others, engagement with possessions and photographs, and use of the deceased as a role model. Following an interdisciplinary review, Kamp et al. (Citation2020) proposed the use of the term “Sensory and Quasi-Sensory experiences of the deceased” (SED) to address sensory and perception-like CBs phenomenon that include visual, auditory, tactile, and olfactory features, or more general sense of the deceased being somehow present or nearby. SED includes seeing the deceased appear, receiving communication from them, hearing their voice, or sensing their presence. SEDs have been conceptualized as continued presence (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016), anomalous experiences (Cooper, Citation2017), sense of presence (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011), bereavement hallucinations (Grimby, Citation1993; Kamp et al., Citation2019; Olson et al., Citation1985; Rees, Citation1971), after death communication (Daggett, Citation2005) and spiritual experiences (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014; Sormanti & August, Citation1997).

CBs research has distinguished adaptive and maladaptive potentials following bereavement (Field et al., Citation2003; Stroebe & Schut, Citation2005). In accordance with attachment theory, the internalization of CBs as a secure base is considered adaptive, whereas externalized CBs, such as hallucinations and illusions are associated with unresolved loss (Field & Filanosky, Citation2010). While some associate CBs with concurrent meaning reconstruction (Klass et al., Citation2014), others conceptualize it as a proximity-seeking behavior and loss avoidance strategy that prolongs grief (Maccallum & Bryant, Citation2013). Despite investigation, studies have been unable to confirm whether retaining, rather than relinquishing bonds is helpful following bereavement (Root & Exline, Citation2014; Stroebe & Schut, Citation2005). Research has therefore turned to examine determinants and consequences of types and facets of CBs.

Until recently, research into CBs has emphasized the measurement of grief-related distress as a marker of adjustment (Stroebe et al., Citation2012; Stroebe & Schut, Citation2005). As findings are complicated by the overlapping nature of CBs and grief (Schut et al., Citation2006) some argue that CBs may be one of the ways that grief manifests (Kamp, Moskowitz, et al., Citation2022). Though associations between CBs are well-supported (Field et al., Citation2013; Lalande & Bonanno, Citation2006; Lipp & O’Brien, Citation2022), research is beginning to show that CBs have the potential to bring practical, spiritual, and meaning-orientated outcomes that point to adaptive potentials (Black et al., Citation2022; Field et al., Citation2013; Field & Filanosky, Citation2010; Lipp & O’Brien, Citation2022; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006; Stroebe & Schut, Citation2005). Authors have therefore called for a reconceptualization of what constitutes a “good outcome” following bereavement (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011).

Aims of the review

This review builds on knowledge of CBs and their impact on bereavement outcomes, seeking to synthesize existing literature and identify gaps for further research. Previous reviews have examined the integration of attachment theory, bereavement models (Stroebe et al., Citation2010), CB type (Kamp et al., Citation2020), and the impact of suicide and traumatic loss on CBs (Goodall et al., Citation2022). The current review aims to explore a broader question “How do CBs impact bereavement?” It is the first review to systematically collate and synthesize evidence concerning the role and impact of CBs for the bereaved, across a range of outcomes.

Methods

Protocol and registration

A review protocol was developed following PRISMA-P guidelines and registered on the Prospero international prospective register of systematic reviews related to health and social sciences (see https://www.crd.yor.ac.uk/prospero, registration number: CRD42021227075).

Eligibility criteria

Studies were eligible if they reported on the experience or impact of CBs following bereavement in adults (18 years upwards). CBs were defined as a continued bond with a significant other, after their death. A general unified category for CBs included engaging with memories, possessions, sense of presence experiences, after-death communication, voices, visions, and spiritual experiences. Studies had to report qualitative or quantitative outcomes following bereavement (e.g., grief, post-traumatic growth, meaning). Only studies reporting the loss of a person, and not pets, were included. Only empirical quantitative and/or qualitative research published in English were included. No restrictions were placed on the publication date or location of the research.

Information sources and systematic search

The scope of the review was identified using the Context, How, Issues, Population (CHIP) tool outlined by Shaw (2010). Context attended to bereavement; How addressed the inclusion of qualitative and quantitative studies; Issues addressed the impact and experience of CBs, and Population addressed a focus on bereaved adults. A search strategy was structured using key search terms combined with AND/OR (Boolean logic). Search terms included: bereavement OR grief OR mourning AND “continuing bond*” OR presence OR “afterlife” OR “after death communication” OR “bereavement hallucination” NOT PETS. The strategy was used to systematically search the following electronic databases from inception until February 2021: PsycINFO, CINAHL, Pubmed, Psychology and Behavioral Sciences Collection, SOCINDEX, and Web of Science. Grey literature was identified by searching Ethos e-theses, and by screening the reference lists of included studies. A search of Google Scholar was conducted in February 2023 to capture newly published studies and reports.

Study selection

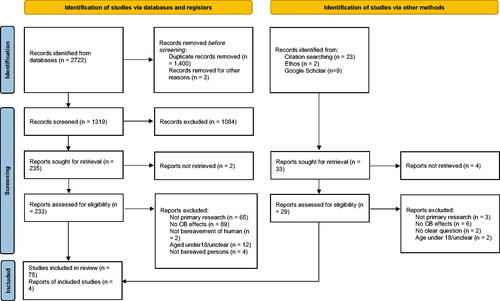

Studies were downloaded into reference management software (Zotero). Following the removal of duplicate papers, abstracts were screened to remove irrelevant articles. Papers identified as relevant to the research question were then read in full and screened against the inclusion criteria by HH. A 10% sample of full-text reports was independently screened by GH. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or involvement of a third member of the research team, CJ. Further papers were sought by reference chaining and citation checking (see ). Common exclusions included a lack of focus on the impact of CBs or the impact on bereavement.

Figure 1. PRISMA Diagram reporting the study selection process. PRISMA preferred reporting guidelines for systematic reviews and meta-analysis. From: Page et al. (Citation2021). For more information, visit: http://www.prisma-statement.org/

Data extraction and management

Study findings were extracted using a pre-designed extraction form, uploaded to NVivo software, version 12. Data were extracted on the study aim, country, setting, study design, and findings. In accordance with Popay et al. (Citation2006), findings from quantitative studies were summarized as a qualitative description to accommodate analysis.

Data synthesis

To account for heterogeneity in study designs, narrative synthesis, and thematic analysis were conducted (Popay et al., Citation2006; Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The thematic analysis provided a flexible framework compatible with the analysis of both constructivist and essentialist paradigms within a mixed-studies design (Clarke & Braun, Citation2021). The preliminary synthesis included generating a textual summary of the quantitative findings to enable an analysis of the entire data set. The analysis involved inductive coding, organization of codes into descriptive themes, and use of research aims as a framework for interpretation (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). The analysis enabled the categorization of the data in relation to the research question to summarize meaningful themes. As such, each theme captured something important about the data, representing a patterned response (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008). An inductive and integrative approach to coding was maintained to allow important themes and topics to develop from the findings. Only those themes which answered the review question were included in the final synthesis.

Quality assessment

Included studies were reviewed for quality using the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT). HH appraised each study and compared the results with a sample appraised by GH. Key information regarding included studies can be viewed within the Supplementary Files (see Supplementary Tables 1–3).

Table 1. Summary of quality assessment of included studies using the MMAT (N = 79).

Findings

Searches

Initial searches identified 1319 records after duplicate removal. 1083 were excluded following abstract and title screening. Of 236 records assessed for full-text eligibility, 172 were excluded. Key reasons for exclusion included that the study did not describe or measure the effect of CBs within the context of grief or bereavement. Seventy-nine studies were included in the final synthesis representing the experience and influence of continuing bonds for ∼13,366 bereaved individuals. summarizes the quality of included papers in accordance with the MMAT.

Study characteristics

Included studies were conducted in the USA (n = 36), UK (n = 25), Canada (n = 5), Israel (n = 7), China (n = 4), Italy (n = 2), Germany (n = 1), Portugal (n = 2), Australia (n = 1), Japan (n = 2), Turkey (n = 1), and Scandinavia (n = 9). Participants were recruited from bereavement services, bereavement forums, universities, and other community settings. The proportion of participants reported to be women was 73 with 22% of participants reported as men. Three studies explored CBs and SEDs within a male-only sample (Mahat-Shamir et al., Citation2022; Richards et al., Citation1999; Troyer, Citation2014). Reporting of ethnicity was inconsistent, but where reported, White and Christian participants were consistently overrepresented. Studies differed regarding the definition of CBs as a unidimensional or multi-faceted construct. Sample sizes in quantitative studies ranged from 30 to 1031 and drew upon a range of descriptive, correlational, cross-sectional, longitudinal, cohort, and within-person designs. Qualitative studies reported sample sizes ranging from 1 to 50 and incorporated case studies, interview studies, and qualitative survey designs. The review incorporated a similar number of qualitative (n = 34) and quantitative (n = 38) studies with a smaller number using mixed methods (n = 7). Cross-sectional and prospective longitudinal studies explored associations between CBs and bereavement outcomes (e.g., grief, post-traumatic growth) in combination with other known correlates (e.g., attachment style, personality, depression, expectedness of loss, bereavement type, trauma). Qualitative and quantitative descriptive studies explored participants’ experiences of CBs and grief more generally.

Quality appraisal

The most frequent methodological weaknesses within quantitative studies related to nonresponse bias, with response rates reported in only a handful of studies. Within the qualitative papers, similar approaches to recruitment limited heterogeneity within the sample. Consensus regarding the definition of CBs was heterogeneous with studies drawing upon constructed items, use of the Continuing Bonds Scale, and participant constructions of meaning within qualitative studies. Finally, the included studies varied greatly in terms of study design with significant heterogeneity in study samples and measurement instruments limiting comparability.

Thematic findings

Synthesis of the findings generated three key themes: Comfort and distress; Ongoing bonds and relational identity; and Uncertainty, conceptualizing, and spirituality.

Comfort and distress

Comforting presence versus discomforting absence

Across studies, CBs brought comforting memories of the deceased into the present (Black et al., Citation2021; Bird, Citation2002; Grimby, Citation1993; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Kamp, Steffen, et al., Citation2022; Kamp et al., Citation2021; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Comfort was relevant to a wide range of CBs types including engaging with memories (Bailey et al., Citation2015; Boelen et al., Citation2006; Rubin & Shechory-Stahl, Citation2013), after-death communication (Daggett, Citation2005; Elsaesser et al., Citation2021; Kasket, Citation2012), spiritual experiences (Horie, Citation2016; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014; Sormanti & August, Citation1997), keeping possessions (Goldstein et al., Citation2020), SEDs (Black et al., Citation2022; Datson & Marwit, Citation1997; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Kamp et al., Citation2020, Citation2021; Longman et al., Citation1988; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Troyer, Citation2014), dreams of the deceased (Black et al., Citation2021) and mediumship (Testoni et al., Citation2020, Citation2022). Comforts derived from bonds were associated with a sense of the deceased being somehow nearby (Longman et al., Citation1988; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011), accommodating feelings of accessibility, connection, and communication (Bailey et al., Citation2015; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Hearing the deceased’s voice or communicating with them was shown to provide valued opportunities to say goodbye, wish the deceased well, or extend the relationship to benefit from posthumous support (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Kasket, Citation2012; Parker, Citation2005; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011). As spiritual experiences, further benefits were shown to include confirmation that the deceased is at peace within the afterlife, lessening of existential concerns, and hope of reunion (Asai et al., Citation2012; Austad, Citation2015; Black et al., Citation2022; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018; Kamp et al., Citation2019; Kawashima & Kawano, Citation2017; Parker, Citation2005; Sormanti & August, Citation1997; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Testoni et al., Citation2022; Wright et al., Citation2014).

Through direct and symbolic communication, CBs were shown to offer instruction, remind the deceased to carry out tasks, and enable adaptation to new responsibilities (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2005; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011). This communication was deemed particularly beneficial when the bereaved experienced social loneliness, isolation, and day-to-day problems (Chan et al., Citation2005; Conant, Citation1996; Florczak & Lockie, Citation2019; Grimby, Citation1993; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2005; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011).

It is important to note that comfort was shown to occur within the context of distress and sadness about the loss (Black et al., Citation2021; Bird, Citation2002; Grimby, Citation1993; Kamp, Steffen, et al., Citation2022; Kamp et al., Citation2021; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Thus, CBs incorporated discomforting absence, and the foregrounding of grief (Foster et al., Citation2011; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018). This aspect of CBs is illustrated by online memorial use which lessened discomfort associated with forgotten memories and the diminishing of deceased’s life, but evoked fear of reseparation and secondary loss due to deleted content (Bailey et al., Citation2015). Similarly, Hayes and Leudar (Citation2016) show how voices and illusions experienced soon after bereavement brought loss into focus with comfort giving way to the amplification of grief. The oscillation between comforting presence and discomforting absence, or dominance of the latter, was abated by disengagement from CBs (Bird, Citation2002; Foster et al., Citation2011; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Leichtentritt & Mahat-Shamir, Citation2017; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022). Highlighting both comfort and distress, Field and Friedrichs (Citation2004) showed that following the acute phase of grief CBs facilitated positive, rather than negative mood as it did soon after the loss. Supporting this, benefits derived from CBs have further been associated with the extent to which the bereaved are able to make sense of the death in personal, practical, and spiritual terms (Keser & Işıklı, Citation2022; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006).

Bereavement related distress

For a minority of participants, CBs were sometimes unhelpful, bringing heightened distress, loneliness, and a sense of threat indicative of post-traumatic stress (Black et al., Citation2022; Field et al., Citation2013; Harper et al., Citation2011; Kamp, Steffen, et al., Citation2022; Kamp et al., Citation2021; Keser & Işıklı, Citation2022; Lindstrom, Citation1995; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Testoni et al., Citation2020; Yu et al., Citation2016). Distressing emotional processes included negative mood (Field & Friedrichs, Citation2004), fear (Austad, Citation2015; Kamp et al., Citation2021), heightened grief (Boulware & Bui, Citation2016; Field et al., Citation2013; Lalande & Bonanno, Citation2006; Lipp & O’Brien, Citation2022), separation distress (Epstein et al., Citation2006; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006), guilt and blame (Black et al., Citation2022; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Sormanti & August, Citation1997; Testoni et al., Citation2020), fear of upsetting others (Bird, Citation2002), family tensions (Bailey et al., Citation2015; Foster et al., Citation2011; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011), and concern for one’s mental health (Kamp et al., Citation2021; Keen et al., Citation2013). Following suicide bereavement, Jahn and Spencer-Thomas (Citation2018) reported 4.8% of their sample experienced spiritual experiences of the deceased as harmful with negative appraisals of spiritual experiences including interpretation of the deceased as not at peace (e.g., “I think she may be stuck in limbo and unhappy,” p. 248).

Where CBs were associated with heightened grief, features of the pre-death relationship that complicated the grief process. These included: dependency (Bird, Citation2002; Mancini et al., Citation2015), loss of a child (Field et al., Citation2013; Field & Filanosky, Citation2010), greater closeness (Kamp et al., Citation2020), avoidant attachment (Ho et al., Citation2013; Currier et al., Citation2015; Kamp et al., Citation2020), conflict in the relationship (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Sormanti & August, Citation1997; Testoni et al., Citation2020). Unfinished business was associated with blame, regret, and more distressing and conflictual CBs expressions (Black et al., Citation2022; Parker, Citation2005). Lack of preparedness, unexpected death, violent death, and suicide bereavement were shown to complicate accommodation of the death with CBs bringing distress (Field et al., Citation2013; Field & Filanosky, Citation2010; Ho et al., Citation2013; Currier et al., Citation2015; Parker, Citation2005; Stroebe et al., Citation2012; Yu et al., Citation2016). Following child loss, 26.4% of bereaved mothers associated transitional objects with heightened distress (Goldstein et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the experience of fetal movement, as if the child had not been born, produced significant distress following a miscarriage or perinatal loss (Testoni et al., Citation2020). Moreover, the intense grief felt following child loss was associated with ambivalence about personal mortality and hope for a reunion (Harper et al., Citation2011).

Building on the association between CBs and distress, delineation between internalized and externalized bonds has shown the greater association of externalized bonds with bereavement distress, post-traumatic distress, and complicated grief (Black et al., Citation2022; Ho et al., Citation2013; Epstein et al., Citation2006; Field et al., Citation2013; Field & Filanosky, Citation2010; Kamp et al., Citation2020; Ronen et al., Citation2009; Scholtes & Browne, Citation2015). Distinct facets of CBs were further shown to impact differently with keeping possessions associated with heightened grief when compared with memories; and dreaming and yearning for the deceased associated with greater and more intense separation distress when compared to the sense of presence (Boelen et al., Citation2006; Epstein et al., Citation2006; Keser & Işıklı, Citation2022). In their research, Kamp, Moskowitz, et al. (Citation2022) show that SEDs brought greater emotional loneliness, prolonged grief, and PTSD at 6 months, though when compared to non-experiencers, a similar trajectory for reducing bereavement-related stress was observed at 18 months post-loss.

Non-disclosure and social stigma

Stigma and non-disclosure were consistent findings. Following SEDs, individuals sought support from communities perceived to be more accepting (Kamp et al., Citation2021; Keen et al., Citation2013; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Beyond this, the bereaved described an expectation for SED and other forms of CB expression to meet challenge and rejection (Keen et al., Citation2013; Testoni et al., Citation2022) along with worry about how their continued relationship would be viewed (Keen et al., Citation2013; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Stigma and non-disclosure were associated with fear that others view encounters with the deceased as maladjusted or associated with mental illness (Austad, Citation2015; Keen et al., Citation2013; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Taylor, Citation2005; Testoni et al., Citation2022; Troyer, Citation2014). Dismissive and marginalizing responses from others were reported, for example, “people think I should move on,” “people think I’m crazy” (Sabucedo et al., Citation2021, p. 473). Following a suicide, Jahn and Spencer-Thomas (Citation2018) describe familial concerns that CBs may elevate risk of suicide. Familial tensions were also described initially by Bird (Citation2002) and supported by Steffen and Coyle (Citation2011) who describe differing responses depending on spiritual belief and bereavement trajectory.

Ongoing bonds and relational identity

Identity processes and personal growth

Communication with the deceased, whether online, speaking aloud, or through imagined dialogue, was shown to bring a sense of everyday continuity (Bailey et al., Citation2015; Carnelley et al, Citation2006; Kasket, Citation2012; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Stemen, Citation2022) and interrelatedness (Daggett, Citation2005; Harper et al., Citation2011). Qualitative studies show how CBs continue roles and identities after bereavement (Bird, Citation2002; Conant, Citation1996; Harper et al., Citation2011; Leichtentritt et al., Citation2016; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011). Harper et al. (Citation2011) reported that keeping the graveside clean and tidy extended a nurturing role, with mothers viewing this as “something I can still do” (p. 207). Similarly, Steffen and Coyle (Citation2011) presented a sense of presence as maintaining the experience of motherhood. Following widowhood, Conant (Citation1996) showed that ongoing relationships were orientated around a desire for widows to continue caring for their husbands. Moreover, through sensing the deceased as present, the bereaved derived that the deceased continued to care for them (Chan et al., Citation2005; Conant, Citation1996), with this serving as a source of self-esteem (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011).

Neimeyer et al. (Citation2006) showed that although heightened identity reconstruction increased separation distress; sensemaking, CBs, and positive identity change, brought a reduction in bereavement distress. Further to this, several studies show how CBs support identity transformation (Asai et al., Citation2012; Bird, Citation2002; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Kawashima & Kawano, Citation2017; Mahat-Shamir et al., Citation2022; Marwit & Klass, Citation1995; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). For example, the bereaved have been shown to imagine their afterlife with the person and to make resolutions to find purpose in life (Asai et al., Citation2012). Chan et al. (Citation2005) showed that adopting a similar vision or seeking to finish the work of the deceased provided a source of meaning. Similarly, Bird (Citation2002) showed how statements, such as “What they [the deceased] would have wanted” (p. 65) were used as a source of motivation, reinforced by the deceased spouse directly, or indirectly, through the sense of presence. Moreover, constructing the deceased as a role model involved an imaginal commitment to live life in accordance with the values, desires, and personal characteristics of the deceased along with an eagerness to live up to their wishes with this informing future life choices (Asai et al., Citation2012; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Kawashima & Kawano, Citation2017; Mahat-Shamir et al., Citation2022; Marwit & Klass, Citation1995; Pearce & Komaromy, Citation2022).

Several studies show that CBs brought spiritual and post-traumatic growth (Albuquerque et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Black et al., Citation2022; Elsaesser et al., Citation2021; Parker, Citation2005; Richards et al., Citation1999; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Scholtes & Browne, Citation2015; Stein et al., Citation2018; Yu et al., Citation2016). Although Black et al. (Citation2022) demonstrated that post-traumatic growth followed internalized and externalized CBs, Scholtes and Browne (Citation2015) show post-traumatic growth for internalized bonds only. Albuquerque et al. (Citation2018) reported that internalized bonds, “saying goodbye,” and resilience, significantly increased personal growth, with the effect size attributable to these factors reported as medium to large [Cohen’s f2 = 0.30]. Importantly, findings show that spiritual interpretations and expressions of CBs may contribute to the strengthening of spiritual belief and the lessening of existential concerns (Elsaesser et al., Citation2021; Parker, Citation2005).

Evolving relationships with the deceased: death, unfinished business, agency, and purpose

The studies show that CBs are dynamic with the integration of information accommodating the relocation of the deceased. CBs and SEDs assist the bereaved to tolerate absence, whilst retaining access through recognition of their existence in the afterlife (Keen et al., Citation2013), on a different plane (Daggett, Citation2005), as a spiritual figure (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014), or through internalized memories (Field & Filanosky, Citation2010). Steffen and Coyle (Citation2011) showed how this changed relationship assumed an “as if” quality with the deceased being “somehow” or “almost” present in the life of the bereaved. Envisaging the deceased in the afterlife, or as older and more mature adults, extended narratives into the future, allowing an alternate, less radical ending to the relationship and to the storied description of events leading up to the death (Rubin & Shechory-Stahl, Citation2013).

Dialogical and emotional processes were shown to shape the relationship by providing opportunities for missed goodbyes (Albuquerque et al., Citation2018; Bailey et al., Citation2015; Conant, Citation1996; Cooper, Citation2017; Daggett, Citation2005; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021) and the processing of guilt, and forgiveness (Chan et al., Citation2005; Gassin & Lengel, Citation2014; Parker, Citation2005). Sormanti and August (Citation1997), described how feelings of guilt were resolved when parents experienced connections with their deceased child, as evidence that they were letting their child go, and that letting go was acceptable. Research by Chan et al. (Citation2005) described how mediumship facilitated a lessening of guilt upon receiving contact. The studies show that through dialogue, sense of presence, visions, and voices, provided opportunities to resolve unfinished business concerning the relationship, or the death itself (Chan et al., Citation2005; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2005; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Testoni et al., Citation2020). Parker (Citation2005) found that when this was resolved the bereaved experienced greater comfort and less distress from CBs.

Interestingly, the studies showed that the bereaved placed emphasis on positive and valued aspects of the deceased and remember them in particular ways (Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Rubin & Shechory-Stahl, Citation2013). CBs were often active and purposeful, orienting the bereaved toward agency in the processing of grief. Foster et al. (Citation2011) showed how parents selected photographs, videos, belongings, and scrapbooks as reminders. The agency was evident in bodily inscription through memorial tattoos (Cadell et al., Citation2022), engagement with online legacy pages (Bailey et al., Citation2015), funerary rites, rituals (Pang & Lam, Citation2002), and following SED, through seeking contact and wishing the dead would come (Austad, Citation2015). Suhail et al. (Citation2011) described some of the ways participants recited the Quran to seek forgiveness and ease the transition to the afterlife. This positive framing of the lost relationship around good intentions and socially desirable traits emphasized positive rather than negative memories of the deceased allowing the relationship to evolve (Foster et al., Citation2011; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Suhail et al., Citation2011).

Uncertainty, conceptualizing, and spirituality

Questioning vs. qualifying

SEDs left the bereaved questioning the reality and meaning of contact with the deceased (Conant, Citation1996; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014). Though spiritual worldviews and prior experience increased expression and engagement in SEDs (Chan et al., Citation2005; Kamp et al., Citation2019; Simon-Buller et al., Citation1989), competing explanations were associated with confusion, distress, and worry about deteriorating mental health (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018; Keen et al., Citation2013; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021). Acceptance of SEDs as real required the bereaved to resist perspectives emanating from psychiatric, religious, and cultural discourses (Conant, Citation1996, Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Stemen, Citation2022). Studies showed that the bereaved wrestled with competing frameworks, with spiritual interpretations, inconsistently doubted and believed (Conant, Citation1996; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Troyer, Citation2014). Troyer (Citation2014) showed how widowers drew upon internal (e.g., “My mind was tricking me,” p. 642) and external (e.g., “a sign from heaven,” p. 642) frames of reference to explain post-death encounters with uncertainty accommodating hopeful anticipation of future contact. Traditional discourses, such as “involvement of the mind” and reports of similar experiences by others have been shown to help the bereaved to reconcile tensions whilst retaining a commitment to veridicality (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011). The presence of auditory, olfactory, tactile, and visual experiences was used to qualify encounters as real and tangible (Austad, Citation2015; Troyer, Citation2014). Furthermore, clarity of auditory perceptions and recognizable visual characteristics validated the attribution of sense of presence phenomena belonging to a particular deceased person. Other visual cues included the presence of feathers, butterflies, and the movement of objects (Stemen, Citation2022; Testoni et al., Citation2020). Several studies demonstrate that the bereaved emphasis on the benefits, meaning, and process of engaging with continuing bonds rather than on the mechanisms underlying continued contact is sufficient to accommodate them (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018; Pang & Lam, Citation2002; Stein et al., Citation2018).

Spiritual frameworks for meaning

Spiritual worldview explained a greater reporting of sensory and quasi-sensory experiences of the deceased (Kamp et al., Citation2019). Moreover, SEDs contribute to changes in spiritual and religious belief with this bringing comfort and a reduction in fear of death (Keen et al., Citation2013; Parker, Citation2005; Penberthy et al., Citation2021). Changes to spiritual belief included the expansion of religious frameworks of heaven and hell to incorporate the presence of spirits on Earth (Austad, Citation2015; Elsaesser et al., Citation2021; Parker, Citation2005; Richards et al., Citation1999; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021); belief in life after death (Penberthy et al., Citation2021); para-physiological interpretations including hierarchical planes of consciousness (Austad, Citation2015); reincarnation, and belief in an eternal soul (Austad, Citation2015; Conant, Citation1996; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009). Belief in an afterlife brought hope of reunion with death viewed as a temporary separation (Chan et al., Citation2005, Daggett, Citation2005; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014; Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Testoni et al., Citation2020). Although SEDs did not necessarily align with religious belief (Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018; Penberthy et al., Citation2021), negative attribution of EDs (i.e., “stuck in limbo,” p. 248) was associated with religious frameworks (Austad, Citation2015; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2018). Spiritual interpretation therefore emerged as playing a key role in the comforting nature of CBs (Field et al., Citation2013; Grimby, Citation1993; Richards et al., Citation1999) bringing greater openness to uncertainty about the experience, joy, reassurance, love, peace, courage, coping, and hope when compared with medical frameworks (Cooper, Citation2017).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this mixed studies review is the first to systematically review literature that attends to the effect of CBs across a range of outcomes. A key finding is that CBs bring comfort, practical support, and distress, with CBs facilitating oscillation between the comforting presence and absence of the deceased. Considering studies associating some subtypes of CBs with heightened grief (Boelen et al., Citation2006; Field & Filanosky, Citation2010; Kamp et al., Citation2020; Lipp & O’Brien, Citation2022; Schut et al., Citation2006), this finding highlights the relevance of dual-process and two track models of bereavement (Rubin, Citation1999; Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999) in supporting orientation to both restorative and loss orientated coping soon after the loss. Taken together, findings that address the association of CBs with bereavement-related distress highlight that CBs could be one of the cognitive, behavioral, and psychological ways in which grief manifests, rather than an indicator of prolonged grief disorder or complicated grief. Moreover, given studies addressing the adaptive role of meaning reconstruction following bereavement (Keser & Işıklı, Citation2022; Milman et al., Citation2017; Neimeyer et al., Citation2006), findings that address the role of CBs in accommodation of the loss, evolution of the relationship, identity processes, agency and the expansion of spiritual belief are pertinent and show how CBs may facilitate this. A positive ongoing relationship has been shown to affirm and transform identity (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011; Stein et al., Citation2018), as well as spiritual belief (Penberthy et al., Citation2021), with further restorative functions including support for new roles, clarification of values, new identities, and use of the deceased as a role model (Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Marwit & Klass, Citation1995; Suhail et al., Citation2011). Given that bereavement, distress is heightened when loss destabilizes the self (Maccallum & Bryant, Citation2013; Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999) further research that addresses the role of CBs in supporting positive identity processes would be worthwhile.

Though CBs are comforting for most, the finding that distressing experiences may be associated with higher levels of predeath conflict and closeness has important implications for bereavement care providers (Black et al., Citation2022; Gassin & Lengel, Citation2014; Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Parker, Citation2005; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021; Sormanti & August, Citation1997; Testoni et al., Citation2020). Where CBs extend conflictual relationships into the present, maintaining lower levels of self-agency, or incorporate limited mutuality; meaning reconstruction and resolution of unfinished business may be hampered. Moreover, cultural traditions that stigmatize speaking ill of the dead may limit opportunities for the bereaved to disclose or seek emotional support (Klass & Walter, Citation2001). Importantly, the current findings highlight that CBs may be dynamic rather than static, providing opportunities for a changed relationship that integrates new information. As such, research that explores experiences of working through conflict and addressing unfinished business may help bereavement service providers to increase the accessibility of services for this group.

Though the review has focused on the role of CBs following bereavement, findings support health-promoting approaches to palliative care and highlight the importance of promoting a “good death” to improve outcomes for the bereaved (Kellehear, Citation1999; Aoun et al., Citation2018). There are further opportunities to consider how a long course of illness, caregiving relationship, or anticipatory grief might impact CBs, along with consideration of changes to the pre-death relationship that may occur within the context of chronic illness or because of Alzheimer’s and dementia.

Despite its strengths, findings from this review need to be understood within the context of the methodological limitations of the studies included. Most studies have been conducted on females, from White backgrounds and Christian faith. The research has drawn upon a variety of measures to assess adjustment to loss; these include measures developed specifically for symptoms of grief, post-traumatic growth, and qualitative analysis of interviews, but as most CBs research has not used a longitudinal design, it is not possible to draw conclusions upon their long-term impact, or upon what mediates change over time in respect of adjustment. Further to this, the direction of relationships between distressing experiences and CBs remains unclear. A further limitation is concerned with the broad range of terms utilized to identify CBs manifestations, with this limiting the degree to which different forms of CBs can be compared.

Nevertheless, the review contributes unique findings to the wider field of bereavement as well as to counseling and psychotherapy literature. Practitioners should be aware that CBs foreground both presence and absence, bringing loss into focus. In accordance with dual process theory (Stroebe & Schut, Citation1999), the bereaved could be encouraged to engage in loss-orientated and restorative aspects of CBs. Bereavement practitioners should also normalize the various forms of engagement with CBs, particularly when these emerge as external representations of the deceased, or when these are associated with distress, stigma, and a fear of “going crazy.” The bereaved may benefit from addressing unfinished business regarding the death, or the pre-death relationship, with CBs providing an opportunity to express forgiveness, say goodbye, or integrate further information regarding the life and death of the deceased (Albuquerque et al., Citation2018; Bailey et al., Citation2015; Chan et al., Citation2005; Cooper, Citation2017; Daggett, Citation2005; Gassin & Lengel, Citation2014; Hussein & Oyebode, Citation2009; Parker, Citation2005; Sabucedo et al., Citation2021, Testoni et al., Citation2020). Given that spiritual interpretation is often beneficial, bereavement care should attune to spiritual interpretations of CBs but clinicians should be aware that negative associations with the afterlife may bring distress, particularly when the presence of the deceased is unwelcome, experienced as threatening, or when the deceased is perceived to be stuck in limbo (Hayes & Leudar, Citation2016; Jahn & Spencer-Thomas, Citation2014). Considering the range of explanatory frameworks utilized to contextualize SED adoption of a pluralist perspective that retains uncertainty regarding the underlying mechanisms may be beneficial (Steffen & Coyle, Citation2011). As CBs bring benefits outside of grief clinicians should consider the broader functions that CBs and SEDs might serve. In some instances, this may highlight opportunities to attune to attachment insecurity, and self-esteem, or to address social vulnerabilities that further complicate adjustment to loss. Within the context of social loneliness, family tensions, or isolation, the bereaved may therefore benefit from engagement with compassionate communities (Aoun et al., Citation2018).

The question of the impact of CBs on bereavement has been shown to be complex impacting emotional, cognitive, and social processes. The field would benefit from expanding definitions of adjustment to loss to incorporate posttraumatic growth, values clarification, spiritual growth, meaning reconstruction, the transformation of identity, social and behavioral adaptation alongside the measurement of grief. It will be interesting for further studies to assess how CBs are affected by mediating factors mentioned within this review, that is, preparedness for death, death circumstances, identity processes, spirituality, afterlife belief, and sense-making. There is a further need for research that attends to broader cultural frameworks for meaning. Though studies have shown that CBs play a role in identity processes these findings have been exploratory, relying on qualitative designs. More research is therefore needed to define and quantify the impact of CBs on identity continuity and self-esteem. Given the evidence that points to unfinished business and conflict as driving distressing experiences, research is needed to maximize attempts to resolve unfinished business and its impact on the bereaved.

Conclusion

Through engaging with memories and SED, Continuing Bonds appear to benefit the bereaved by providing comfort, accommodating the circumstances of the death within a coherent narrative or story, supporting meaning reconstruction, the transformation of self-identity, and affirmation of spiritual belief. These findings suggest that CBs and interventions which promote meaning reconstruction and accommodate spiritual interpretations of CBs should not be discouraged. More research is needed to define and maximize the potential benefits of CBs both within and outside of grief and to develop greater knowledge of factors that may underlie and minimize distressing consequences when CBs go awry.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (29.2 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (94.3 KB)Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (91.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Albuquerque, S., Narciso, I., & Pereira, M. (2018). Posttraumatic growth in bereaved parents: A multidimensional model of associated factors. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 10(2), 199–207. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000305

- Albuquerque, S., Narciso, I., & Pereira, M. (2020). Portuguese version of the continuing bonds scale–16 in a sample of bereaved parents. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 25(3), 245–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2019.1668133

- Aoun, S. M., Breen, L. J., White, I., Rumbold, B., & Kellehear, A. (2018). What sources of bereavement support are perceived helpful by bereaved people and why? Empirical evidence for the compassionate communities approach. Palliative Medicine, 32(8), 1378–1388. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216318774995

- Asai, M., Akizuki, N., Fujimori, M., Matsui, Y., Itoh, K., Ikeda, M., Hayashi, R., Kinoshita, T., Ohtsu, A., Nagai, K., Kinoshita, H., & Uchitomi, Y. (2012). Psychological states and coping strategies after bereavement among spouses of cancer patients: A quantitative study in Japan. Supportive Care in Cancer, 20(12), 3189–3203. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-012-1456-1

- Austad, A. (2015). Passing Away-Passing By’: A qualitative study of experiences and meaning making of post death presence [PhD thesis]. Norwegian School of Theology.

- Bailey, L., Bell, J., & Kennedy, D. (2015). Continuing social presence of the dead: Exploring suicide bereavement through online memorialisation. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 21(1–2), 72–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2014.983554

- Bird, L. (2002). Continuing bonds and difficulty adjusting to marital bereavement [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Birmingham.

- Black, J., Belicki, K., Emberley-Ralph, J., & McCann, A. (2022). Internalized versus externalized continuing bonds: Relations to grief, trauma, attachment, openness to experience, and posttraumatic growth. Death Studies, 46(2), 399–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1737274

- Black, J., Belicki, K., Piro, R., & Hughes, H. (2021). Comforting versus distressing dreams of the deceased: Relations to grief, trauma, attachment, continuing bonds, and post-dream reactions. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 84(2), 525–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820903850

- Boelen, P. A., Stroebe, M. S., Schut, H. A. W., & Zijerveld, A. M. (2006). Continuing bonds and grief: A prospective analysis. Death Studies, 30(8), 767–776. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600852936

- Boulware, D. L., & Bui, N. H. (2016). Bereaved African American adults: The role of social support, religious coping, and continuing bonds. Journal of Loss and Trauma, 21(3), 192–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/15325024.2015.1057455

- Cadell, S., Lambert, M. R., Davidson, D., Greco, C., & Macdonald, M. E. (2022). Memorial tattoos: Advancing continuing bonds theory. Death Studies, 46(1), 132–139. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1716888

- Carnelley, K. B., Wortman, C. B., Bolger, N., & Burke, C. T. (2006). The time course of grief reactions to spousal loss: Evidence from a national probability sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(3), 476–492. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.476

- Caserta, M., Lund, D., & Utz, R. (2015). Inventory of Daily Widowed Life (IDWL). In Techniques of grief therapy: Assessment and intervention. Routledge.

- Chan, C. L. W., Chow, A. Y. M., Ho, S. M. Y., Tsui, Y. K. Y., Tin, A. F., Koo, B. W. K., & Koo, E. W. K. (2005). The experience of Chinese bereaved persons: A preliminary study of meaning making and continuing bonds. Death Studies, 29(10), 923–947. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180500299287

- Clarke, V., & Braun, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage Publications Ltd.

- Conant, R. D. (1996). Memories of the death and life of a spouse: The role of images and sense of presence in grief. Continuing Bonds: New Understandings of Grief, 275(3510), 179.

- Cooper, C. E. (2017). [Spontaneous post-death experiences and the cognition of hope: An examination of bereavement and recovery] [PhD thesis]. University of Northampton.

- Currier, J. M., Irish, J. E. F., Neimeyer, R. A., & Foster, J. D. (2015). Attachment, continuing bonds, and complicated grief following violent loss: Testing a moderated model. Death Studies, 39(1–5), 201–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.975869

- Daggett, L. M. (2005). Continued encounters: The experience of after-death communication. Journal of Holistic Nursing, 23(2), 191–207. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898010105275928

- Datson, S. L., & Marwit, S. J. (1997). Personality constructs and perceived presence of deceased loved ones. Death Studies, 21(2), 131–146.

- Elsaesser, E., Roe, C. A., Cooper, C. E., & Lorimer, D. (2021). The phenomenology and impact of hallucinations concerning the deceased. BJPsych Open, 7(5), e148. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2021.960

- Epstein, R., Kalus, C., & Berger, M. (2006). The continuing bond of the bereaved towards the deceased and adjustment to loss. Mortality, 11(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576270600774935

- Field, N. P., & Filanosky, C. (2010). Continuing bonds, risk factors for complicated grief, and adjustment to bereavement. Death Studies, 34(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180903372269

- Field, N. P., & Friedrichs, M. (2004). Continuing bonds in coping with the death of a husband. Death Studies, 28(7), 597–620. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180490476425

- Field, N. P., Gal-Oz, E., & Bonanno, G. A. (2003). Continuing bonds and adjustment at 5 years after the death of a spouse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(1), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.1.110

- Field, N. P., Packman, W., Ronen, R., Pries, A., Davies, B., & Kramer, R. (2013). Type of continuing bonds expression and its comforting versus distressing nature: Implications for adjustment among bereaved mothers. Death Studies, 37(10), 889–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2012.692458

- Florczak, K. L., & Lockie, N. (2019). Losing a partner: Do continuing bonds bring solace or sorrow? Death Studies, 43(5), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1458761

- Foster, T. L., Gilmer, M. J., Davies, B., Dietrich, M. S., Barrera, M., Fairclough, D. L., Vannatta, K., & Gerhardt, C. A. (2011). Comparison of continuing bonds reported by parents and siblings after a child’s death from cancer. Death Studies, 35(5), 420–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.553308

- Gassin, E. A., & Lengel, G. J. (2014). Let me hear of your mercy in the mourning: Forgiveness, grief, and continuing bonds. Death Studies, 38(6–10), 465–475. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2013.792661

- Goldstein, R. D., Petty, C. R., Morris, S. E., Human, M., Odendaal, H., Elliott, A. J., Tobacco, D., Angal, J., Brink, L., & Prigerson, H. G. (2020). Transitional objects of grief. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 98, 152161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2020.152161

- Goodall, R., Krysinska, K., & Andriessen, K. (2022). Continuing bonds after loss by suicide: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2963. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052963

- Grimby, A. (1993). Bereavement among elderly people: Grief reactions, hallucinations, and quality of life. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 87(1), 72–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03332.x

- Harper, M., O'Connor, R., Dickson, A., & O'Carroll, R. (2011). Mothers continuing bonds and ambivalence to personal mortality after the death of their child—An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 16(2), 203–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2010.532558

- Hayes, J., & Leudar, I. (2016). Experiences of continued presence: On the practical consequences of ‘hallucinations’ in bereavement. Psychology and Psychotherapy, 89(2), 194–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12067

- Ho, S. M. Y., Chan, I. S. F., Ma, E. P. W., & Field, N. P. (2013). Continuing bonds, attachment style, and adjustment in the conjugal bereavement among Hong Kong Chinese. Death Studies, 37(3), 248–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.634086

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., Gagnon, M.-P., Griffiths, F., Nicolau, B., O’Cathain, A., Rousseau, M., Vedel, I. & Pluye, P. (2018). Mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT), version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291.

- Horie, N. (2016). Continuing bonds in the Tōhoku disaster area. Journal of Religion in Japan, 5(2–3), 199–226. https://doi.org/10.1163/22118349-00502006

- Hussein, H., & Oyebode, J. R. (2009). Influences of religion and culture on continuing bonds in a sample of British Muslims of Pakistani origin. Death Studies, 33(10), 890–912. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180903251554

- Jahn, D. R., & Spencer-Thomas, S. (2014). Continuing bonds through after-death spiritual experiences in individuals bereaved by suicide. Journal of Spirituality in Mental Health, 16(4), 311–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/19349637.2015.957612

- Jahn, D. R., & Spencer-Thomas, S. (2018). A qualitative examination of continuing bonds through spiritual experiences in individuals bereaved by suicide. Religions, 9(8), 248. https://doi.org/10.3390/rel9080248

- Kamp, K. S., Moskowitz, A., Due, H., & Spindler, H. (2022). Are sensory experiences of one’s deceased spouse associated with bereavement-related distress? OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 26(1), 00302228221078686. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221078686

- Kamp, K. S., O'Connor, M., Spindler, H., & Moskowitz, A. (2019). Bereavement hallucinations after the loss of a spouse: Associations with psychopathological measures, personality and coping style. Death Studies, 43(4), 260–269. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1458759

- Kamp, K. S., Steffen, E. M., Alderson-Day, B., Allen, P., Austad, A., Hayes, J., Larøi, F., Ratcliffe, M., & Sabucedo, P. (2020). Sensory and quasi-sensory experiences of the deceased in bereavement: An interdisciplinary and integrative review. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 46(6), 1367–1381. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbaa113

- Kamp, K. S., Steffen, E. M., Moskowitz, A., & Spindler, H. (2022). Sensory experiences of one’s deceased spouse in older adults: An analysis of predisposing factors. Aging & Mental Health, 26(1), 140–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2020.1839865

- Kamp, K. S., Steffen, E. M., Moskowitz, A., & Spindler, H. (2021). Prevalence and phenomenology of sensory experiences of a deceased spouse: A survey of bereaved older adults. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 00302228211016224.

- Kasket, E. (2012). Continuing bonds in the age of social networking: Facebook as a modern-day medium. Bereavement Care, 31(2), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/02682621.2012.710493

- Kawashima, D., & Kawano, K. (2017). Meaning reconstruction process after suicide: Life-story of a Japanese woman who lost her son to suicide. Omega, 75(4), 360–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222816652805

- Keen, C., Murray, C. D., & Payne, S. (2013). A qualitative exploration of sensing the presence of the deceased following bereavement. Mortality, 18(4), 339–357. https://doi.org/10.1080/13576275.2013.819320

- Kellehear, A. (1999). Health-promoting palliative care: Developing a social model for practice. Mortality, 4(1), 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/713685967

- Keser, E., & Işıklı, S. (2022). Investigation of the relationship between continuing bonds and adjustment after the death of a first‐degree family member by using the Multidimensional Continuing Bonds Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23210

- Klass, D., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. (2014). Continuing bonds: New understandings of grief. Taylor & Francis.

- Klass, D., & Walter, T. (2001). Processes of grieving: How bonds are continued. In M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, W. Stroebe, & H. Schut (Eds.), Handbook of bereavement research: Consequences, coping, and care (pp. 431–448). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10436-018

- Lalande, C. M., & Bonanno, G. A. (2006). Culture and continuing bonds: A prospective comparison of bereavement in the United States and the People’s Republic of China. Death Studies, 30(4), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180500544708

- Leichtentritt, R. D., Mahat Shamir, M., Barak, A., & Yerushalmi, A. (2016). Bodies as means for continuing post-death relationships. Journal of Health Psychology, 21(5), 738–749. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105314536751

- Leichtentritt, R. D., & Mahat-Shamir, M. (2017). Mothers’ continuing bond with the baby: The case of feticide. Qualitative Health Research, 27(5), 665–676. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315616626

- Lindstrom, T. C. (1995). Experiencing the presence of the dead: Discrepancies in ‘The Sensing Experience’ and their psychological concomitants. Omega: Journal of Death & Dying, 31(1), 11–21.

- Lipp, N. S., & O’Brien, K. M. (2022). Bereaved college students: Social support, coping style, continuing bonds, and social media use as predictors of complicated grief and posttraumatic growth. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 85(1), 178–203. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222820941952

- Longman, A. J., Lindstrom, B., & Clark, M. (1988). Sensory-perceptual experiences of bereaved individuals: Additional cues for survivors. The American Journal of Hospice Care, 5(4), 42–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/104990918800500407

- Maccallum, F., & Bryant, R. A. (2013). A cognitive attachment model of prolonged grief: Integrating attachments, memory, and identity. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(6), 713–727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.05.001

- Mahat-Shamir, M., Lebowitz, K., & Hamama-Raz, Y. (2022). ‘You did not desert me my brothers in arms’: The continuing bond experience of men who have lost a brother in arms. Death Studies, 46(2), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1737275

- Mancini, A. D., Sinan, B., & Bonanno, G. A. (2015). Predictors of prolonged grief, resilience, and recovery among bereaved spouses: Predictors of bereavement trajectories. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 71(12), 1245–1258. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22224

- Marwit, S. J., & Klass, D. (1995). Grief and the role of the inner representation of the deceased. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 30(4), 283–298. https://doi.org/10.2190/PEAA-P5AK-L6T8-5700

- Milman, E., Neimeyer, R. A., Fitzpatrick, M., MacKinnon, C. J., Muis, K. R., & Cohen, S. R. (2017). Prolonged grief symptomatology following violent loss: The mediating role of meaning. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(Suppl 6), 1503522. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1503522

- Neimeyer, R. A., Baldwin, S. A., & Gillies, J. (2006). Continuing bonds and reconstructing meaning: Mitigating complications in bereavement. Death Studies, 30(8), 715–738. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600848322

- Olson, P. R., Suddeth, J. A., Peterson, P. J., & Egelhoff, C. (1985). Hallucinations of widowhood. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 33(8), 543–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.1985.tb04619.x

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: an updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pang, T. H., & Lam, C. (2002). The widowers’ bereavement process and death rituals: Hong Kong experiences. Illness, Crisis & Loss, 10(4), 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/105413702236511

- Parker, J. S. (2005). Extraordinary experiences of the bereaved and adaptive outcomes of grief. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 51(4), 257–283. https://doi.org/10.2190/FM7M-314B-U3RT-E2CB

- Pearce, C., & Komaromy, C. (2022). Recovering the body in grief: Physical absence and embodied presence. Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine, 26(4), 393–410. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459320931914

- Penberthy, J. K., Pehlivanova, M., Kalelioglu, T., Roe, C. A., Cooper, C. E., Lorimer, D., & Elsaesser, E. (2021). Factors moderating the impact of after death communications on beliefs and spirituality. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 00302228211029160. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228211029160

- Popay, J., Roberts, H., Sowden, A., Petticrew, M., Arai, L., Rodgers, M., Britten, N., Roen, K., & Duffy, S. (2006). Guidance on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews. A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme Version, 1(1), b92.

- Rees, W. D. (1971). The hallucinations of widowhood. BMJ, 4(5778), 37–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.4.5778.37

- Richards, T. A., Acree, M., & Folkman, S. (1999). Spiritual aspects of loss among partners of men with AIDS: Postbereavement follow-up. Death Studies, 23(2), 105–127. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201109

- Ronen, R., Packman, W., Field, N. P., Davies, B., Kramer, R., & Long, J. K. (2009). The relationship between grief adjustment and continuing bonds for parents who have lost a child. Omega, 60(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.60.1.a

- Root, B. L., & Exline, J. J. (2014). The role of continuing bonds in coping with grief: Overview and future directions. Death Studies, 38(1–5), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2012.712608

- Rubin, S. S. (1999). The two-track model of bereavement: Overview, retrospect, and prospect. Death Studies, 23(8), 681–714. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899200731

- Rubin, S. S., & Shechory-Stahl, M. (2013). The continuing bonds of bereaved parents: A ten-year follow-up study with the two-track model of bereavement. Omega, 66(4), 365–384. https://doi.org/10.2190/om.66.4.f

- Sabucedo, P., Hayes, J., & Evans, C. (2021). Narratives of experiences of presence in bereavement: Sources of comfort, ambivalence and distress. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 49(6), 814–831. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1983156

- Scholtes, D., & Browne, M. (2015). Internalized and externalized continuing bonds in bereaved parents: Their relationship with grief intensity and personal growth. Death Studies, 39(1–5), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.890680

- Schut, H. A. W., Stroebe, M. S., Boelen, P. A., & Zijerveld, A. M. (2006). Continuing relationships with the deceased: Disentangling bonds and grief. Death Studies, 30(8), 757–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600850666

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (1999). The dual process model of coping with bereavement: Rationale and description. Death Studies, 23(3), 197–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811899201046

- Simon-Buller, S., Christopherson, V. A., & Jones, R. A. (1989). Correlates of sensing the presence of a deceased spouse. OMEGA-Journal of Death and Dying, 19(1), 21–30. https://doi.org/10.2190/4QV9-186V-JXTC-4N0B

- Sormanti, M., & August, J. (1997). Parental bereavement: Spiritual connections with deceased children. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 67(3), 460–469. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0080247

- Steffen, E., & Coyle, A. (2011). Sense of presence experiences and meaning-making in bereavement: A qualitative analysis. Death Studies, 35(7), 579–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2011.584758

- Stein, C. H., Petrowski, C. E., Gonzales, S. M., Mattei, G. M., Majcher, J. H., Froemming, M. W., Greenberg, S. C., Dulek, E. B., & Benoit, M. F. (2018). A matter of life and death: Understanding continuing bonds and post-traumatic growth when young adults experience the loss of a close friend. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 27(3), 725–738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-017-0943-x

- Stemen, S. E. (2022). ‘I can’t explain it’: An examination of social convoys and after death communication narratives. Death Studies, 46(7), 1631–1640. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2020.1825296

- Stroebe, M. S., Abakoumkin, G., Stroebe, W., & Schut, H. (2012). Continuing bonds in adjustment to bereavement: Impact of abrupt versus gradual separation. Personal Relationships, 19(2), 255–266. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2011.01352.x

- Stroebe, M., & Schut, H. (2005). To continue or relinquish bonds: A review of consequences for the bereaved. Death Studies, 29(6), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180590962659

- Stroebe, M., Schut, H., & Boerner, K. (2010). Continuing bonds in adaptation to bereavement: Toward theoretical integration. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(2), 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.11.007

- Suhail, K., Jamil, N., Oyebode, J., & Ajmal, M. A. (2011). Continuing bonds in bereaved Pakistani Muslims: Effects of culture and religion. Death Studies, 35(1), 22–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/0748118100376559224501848

- Taylor, S. F. (2005). Between the idea and the reality: A study of the counselling experiences of bereaved people who sense the presence of the deceased. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 5(1), 53–61.

- Testoni, I., Bregoli, J., Pompele, S., & Maccarini, A. (2020). Social support in perinatal grief and mothers’ continuing bonds: A qualitative study with Italian mourners. Affilia, 35(4), 485–502. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109920906784

- Testoni, I., Pompele, S., Liberale, L., & Tressoldi, P. (2022). Limits and meanings to the challenging territory of mediumship. A qualitative study with grievers. European Journal of Science and Theology, 18(3), 97–109.

- Thomas, J., & Harden, A. (2008). Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 8(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

- Troyer, J. M. (2014). Older widowers and postdeath encounters: A qualitative investigation. Death Studies, 38(6–10), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2014.924829

- Wright, S. T., Kerr, C. W., Doroszczuk, N. M., Kuszczak, S. M., Hang, P. C., & Luczkiewicz, D. L. (2014). The impact of dreams of the deceased on bereavement: A survey of hospice caregivers. The American Journal of Hospice & Palliative Care, 31(2), 132–138. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909113479201

- Yu, W., He, L., Xu, W., Wang, J., & Prigerson, H. G. (2016). Continuing bonds and bereavement adjustment among bereaved mainland Chinese. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 204(10), 758–763. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000550