Abstract

This study tested the effects of deep and subtle mortality cues on state autonomy, in addition to the moderating roles of trait autonomy, psychological flexibility, and curiosity. Australian undergraduate students (N = 442) self-reported on moderator variables before being randomly allocated to receive either deep mortality cues, subtle mortality cues, or a control task, and finally reported their state autonomy for life goals. Trait autonomy did not moderate the effect of mortality cues on state autonomy. However, for individuals high on psychological flexibility, any mortality cues led to increased state autonomy compared to the control. For individuals high on curiosity, there was some evidence that only deep mortality cues led to increased state autonomy. These findings help clarify the nature of growth outcomes (in terms of more authentic, autonomous motivation for life goals), and the personal characteristics that facilitate growth-oriented processing of death awareness.

Death awareness can elicit intense anxiety, yet existential psychologists (e.g., May, Citation1950; Yalom, Citation1980) argue that it can also challenge an individual’s worldview, providing an opportunity to revise one’s values and motivations so as to live a more autonomous, “authentic” life. Although this line of reasoning is present in the psychological literature (Martin et al., Citation2004) and holds considerable value to understanding personal growth processes among those exposed to death, very limited empirical research directly examines the construct of autonomy in this context. The present study provides the first experimental tests of whether different forms of mortality cues (stimuli eliciting death awareness) can increase state autonomy, and whether this effect is moderated by trait autonomy, psychological flexibility, and curiosity.

Autonomy is a means of functioning authentically in daily life, whereby one pursues goals that are well-integrated within their value system, rather than goals that are imposed upon them or not fully endorsed (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Ryan & Deci, Citation2004). Autonomy, fundamental to well-being, is underpinned by an unbiased, mindful awareness of one’s beliefs and values, and an openness to evaluate them. Self-determination theory outlines a continuum of motivational types (Ryan & Deci, Citation2002), with intrinsic motivation comprising the most autonomous, driven by interest, enjoyment and/or the inherent value in the activity itself. At the other end of the continuum, extrinsic motivation, driven by the outcomes an activity produces rather than the activity itself, can be more or less autonomous depending on its level of internalization. Integrated and identified motivations are the most autonomous extrinsic motivations, whereby instrumental behaviors are well-aligned with one’s greater value system or consciously endorsed as personally valuable. Extrinsic motivations become non-autonomous when they are introjected—partly internalized but not yet integrated within the self, typically driven by the avoidance of shame or guilt. External motivations are the least autonomous, driven by obtaining rewards, avoiding punishments, or other external forces (e.g., societal demands). According to this framework, research cannot appropriately capture autonomy by simply contrasting intrinsic and extrinsic motivations but must consider the variation in types of extrinsic motivation.

Deep forms of death awareness that are more conscious (Grant & Wade-Benzoni, Citation2009; Vail et al., Citation2012) and/or specific (Cozzolino, Citation2006) often result in personal growth resembling greater autonomy. These processes occur in the context of posttraumatic growth (Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004) and near death experiences (NDEs; Martin & Kleiber, Citation2005). Here, deep mortality cues trigger a reassessment of one’s worldview, and growth occurs when individuals adjust their worldview to accommodate the threatening experience (Park, Citation2010). Growth outcomes commonly include a clarified sense of personal values, re-prioritizing goals toward these, and de-prioritizing extrinsic values (e.g., materialism). In contrast, more subtle forms of death awareness that are non-conscious or comparatively abstract often lead to defensive rather than growth-oriented responses. Terror management theory (TMT; Solomon et al., Citation2004) has demonstrated that subtle mortality cues cause people to inflate their adherence to cultural worldviews (Burke et al., Citation2010). Doing so can provide a sense of security, alleviating the effects of the mortality cues while avoiding processing the cues themselves. These defensive responses involve rigidly affirming preexisting worldviews (e.g., prejudice and stereotyping) and increasing culturally-derived extrinsic motivations (e.g., for materialism).

Experimental evidence indicates that deep (more conscious and/or specific) death awareness elicits growth-oriented outcomes aligned with autonomy. For example (Cozzolino et al., Citation2004), among individuals with more extrinsic values, exposure to deep mortality cues significantly lowered extrinsic behavior (greed), whereas subtle mortality cues significantly increased extrinsic behavior. Among those with less extrinsic values, there were no shifts in extrinsic behavior. Similarly, undergraduate students (Kosloff & Greenberg, Citation2009) devalued extrinsic goals during deep death awareness, but increasingly valued high priority extrinsic goals after subtle death awareness. Also, for those higher in openness to experience (Prentice et al., Citation2018), deep mortality cues elicited shifts toward more intrinsic values. However, to extend the literature and directly demonstrate that death awareness can indeed facilitate increases in autonomy, research must go beyond comparing intrinsic and extrinsic goals and consider the full continuum of autonomy regarding these goals. To this end, Seto et al. (Citation2016) found that deeper recalled experiences related to one’s mortality were associated with higher levels of trait authenticity (partly comprised of autonomous tendencies). Quasi-experimental research has also found that funeral and cemetery workers exposed to deep mortality cues were higher in autonomy than a matched control sample (Arena et al., Citation2022). Despite the ecological validity of these studies, their designs preclude causal inferences.

Beyond the role played by the ostensive depth of mortality cues, individuals differ in their capacity to process death awareness in growth-oriented ways (Cozzolino, Citation2006; Grant & Wade-Benzoni, Citation2009; Vail et al., Citation2012). Thus, the effect of mortality cues on state autonomy may depend on certain personal characteristics serving as moderator variables (Cohen et al., Citation2003). First, it is important to consider individual differences in trait autonomy, in order to extend past research (Cozzolino et al., Citation2004). Individuals may shift from less to more state autonomy, unless they already possess highly autonomous tendencies that are not in need of revision. This expectation aligns with the moderation effect observed by Cozzolino et al. (Citation2004) regarding the related construct of prior extrinsic value orientation. Simultaneously, trait autonomy involves an orientation toward growth (Vail et al., Citation2020), and self-determination theory states that people are most likely to increase their autonomy when they generally “experience a sense of choice, volition, and freedom from external demands” (Ryan & Deci, Citation2002, p. 20). Thus, the opposite effect is also plausible, whereby individuals higher in trait autonomy experience greater increases in state autonomy after contemplating death.

Second, psychological flexibility (Bond et al., Citation2011) describes qualities likely to enhance the growth-oriented processing of death. It involves remaining non-defensively aware of one’s thoughts and feelings in the present moment, to facilitate the flexible adjustment or persistence in behavior to pursue valued outcomes, even in the presence of unwanted internal states. The mindful, non-reactive qualities of psychological flexibility likely enhance the deliberate, conscious processing of death that promote growth responses (Grant & Wade-Benzoni, Citation2009; Vail et al., Citation2012). Moreover, psychological flexibility can increase state autonomy, as an unbiased awareness of one’s values is necessary to acknowledge when behaviors are not autonomous and flexibly adjust them accordingly (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Ryan & Deci, Citation2004).

Thirdly, trait curiosity is comprised of a willingness to embrace rather than avoid the novelty and uncertainty of life, in addition to a proclivity toward expanding one’s experience and understanding (Kashdan et al., Citation2009). Curiosity constitutes an inclination to delve into uncomfortable situations, seeing them as an opportunity to challenge one’s way of thinking, accommodate their worldview and grow as a person. Given the discomfort and uncertainty inherent to death awareness, curious people are more likely to immerse themselves in this challenging experience and approach it as another opportunity for self-expansion. Curiosity is therefore likely to increase state autonomy after contemplating death, as this process necessitates the exploration and revision of one’s identity, and a willingness to face potentially uncomfortable information about oneself (Kernis & Goldman, Citation2006; Ryan & Deci, Citation2004).

The current experiment was the first to test the hypothesis that death awareness can lead to greater state autonomy. We aimed to test whether any mortality cues can increase state autonomy compared to a control, or whether this growth response is limited to deep rather than subtle mortality cues. Although we were interested in the possibility of main effects of mortality cue conditions, testing the moderating roles of certain personal characteristics was considered paramount, particularly given Cozzolino et al. (Citation2004) and Prentice et al. (Citation2018) did not report main effects of mortality cue conditions but only interactions with personal characteristics. To this end, the current study aimed to clarify the contrary potential expectations of trait autonomy as a moderator of mortality-induced growth toward state autonomy and hypothesized that higher flexibility and curiosity would specifically increase such growth.

Method

Participants

An a priori power analysis estimated a required sample size of 476 to achieve 80% power for a conservative effect size (ΔR2 = .02). A total of 466 undergraduate students at an Australian university participated in the study in exchange for partial course credit, although we removed 5 with incomplete data, and 19 who did not follow instructions for the manipulation task (see Supplementary Materials online), resulting in a final sample of 442 participants (74.9% women; estimated achieved power = .77). Participants’ ages ranged from 18–42 years (M = 19.70, SD = 3.39). The mode ethnicity was Caucasian/European (52.7%), followed by Asian (38.9%) and Middle Eastern (4.5%), with 7.5% reporting other ethnicities.

Materials

Global Motivation Scale (GMS; Guay et al., Citation2003) assessed trait autonomy. Participants responded to 3-item subscales reflecting intrinsic, integrated, identified, introjected, and external motivational tendencies, using a 7-point scale (1= not at all agree to 7= completely agree) to indicate why they do things in general; for example, “because they reflect what I value most in life” (integrated). Items from each subscale were summed. To maximize comparability with other measures, we averaged the integrated and identified subscales, similar to other researchers’ approaches (Guay et al., Citation2003; Vallerand & Blssonnette, Citation1992). Also, similar to others (Guay et al., Citation2003; Sheldon & Kasser, Citation1998), we calculated a weighted overall index of trait autonomy by doubling the intrinsic and external motivation subscales before subtracting the non-autonomous from the autonomous subscales: (2*intrinsic + (integrated + identified)/2) – (introjected + 2*external). Higher scores reflect more autonomous relative to non-autonomous tendencies (α = .83). The GMS has previously demonstrated good structural validity, temporal stability and internal consistency among groups of Canadian college students (Guay et al., Citation2003).

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II; Bond et al.,Citation2011) is a 10-item measure of psychological flexibility, e.g., “it’s OK if I remember something unpleasant”. Responses are on a 7-point scale from 1 (never true) to 7 (always true) and items are summed so that higher scores reflect greater flexibility (α = .88). The AAQ-II has previously demonstrated high temporal stability, internal consistency, discriminant validity, and criterion validity among groups of university students, substance abuse outpatients, and bank/financial services employees across the USA and UK (Bond et al., Citation2011).

Curiosity and Exploration Inventory-II (CEI-II; Kashdan et al., Citation2009) is a 10-item assessment of trait curiosity, e.g., “I view challenging situations as an opportunity to grow and learn”. Responses are on a 1 (slightly or not at all) to 5 (extremely) scale and items were summed to form a total score (α = .87). The CEI-II has previously demonstrated good convergent and structural validity, internal consistency, and item discrimination among samples of university students in the USA (Kashdan et al., Citation2009).

Death awareness manipulation comprised one of three tasks. The deep mortality cue condition involved the only previously tested manipulation of this kind (Cozzolino et al., Citation2004), requiring participants to imagine a scenario where they fail to escape a fatal apartment fire. Four open-ended questions follow the scenario, to deepen participants’ contemplation of how they would think and feel in this scenario, how they would act, how it influences their perception of the life they have led until that point, and how their family would react if the scenario had occurred. The subtle mortality cue condition (Rosenblatt et al., Citation1989) involved the most commonly used manipulation within the TMT literature (Burke et al., Citation2010)—two open-ended questions concerning participants’ thoughts, emotions and beliefs regarding their own death. To induce subtle, non-conscious thoughts of death in line with TMT, a previously used distraction task (Greenberg et al., Citation1994) was implemented following these two questions, requiring participants to read a short, affectively neutral excerpt from a short story. As is commonly done in the literature, the control condition involved the same two open-ended questions used in the subtle mortality cue condition, but replacing references to death with references to undergoing a painful dental procedure (Arndt & Greenberg, Citation1999).

Personal Projects Questionnaire (Sheldon & Kasser, Citation1998) assessed state autonomy. Participants first spent at least five minutes brainstorming a minimum of 10 current personal goals. To assess state-level motivations, participants selected the five projects they felt “most motivated to pursue at this point in time” and “in the immediate future”. Four questions were then asked for each selected goal, regarding how much participants pursue them for intrinsic, identified, introjected, and external reasons on a 9-point scale (1= not at all because of this reason to 9= completely because of this reason); e.g., “because you really believe that it is an important goal to have—you endorse it freely and value it wholeheartedly” (identified). Scores for each type of motivation are summed across goals and a weighted overall index of state autonomy is calculated using the formula: (2*intrinsic + identified) – (introjected + 2*external). Higher scores reflect greater overall state autonomy (α = .76). This scale has previously demonstrated good convergent and predictive validity, and acceptable internal consistency among university students in the USA (Sheldon & Kasser, Citation1998).

Procedure

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the university’s Human Research Ethics Committee (protocol 2017/567). Participants completed the study on individual computers in groups of up to 10. After providing informed consent, they answered a brief demographic questionnaire, followed by all scales of moderator variables. Participants were then randomly allocated to one of the three manipulation conditions, deep mortality cues (n = 139 after excluding poor responders), subtle mortality cues (n = 153), or control (n = 150). They finally completed the measure of state autonomy before receiving a full debrief.

Results

All scales were positively intercorrelated to a small–moderate extent at p < .01 (see ). Hierarchical linear regressions were run with state autonomy as the dependent variable (see ). Two contrast-coded condition variables were first calculated using the method outlined by Cohen et al. (Citation2003): the first variable compared both mortality cue conditions vs. control (control= −.67, deep mortality cues= .33, subtle mortality cues= .33,) and the second variable compared deep mortality cues vs. subtle mortality cues (control= 0, deep mortality cues= .5, subtle mortality cues= −.5,). Individual models were run to test the interactive effects between the condition variables and each moderator separately. Main effects were entered in the first step, followed by interaction terms in the second. A combined model was then run to examine the unique effects of each variable when entered simultaneously.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and zero-order correlations for all measures.

Table 2. Hierarchical linear regressions testing the interactive effects of mortality cues, trait autonomy, flexibility, and curiosity on state autonomy.

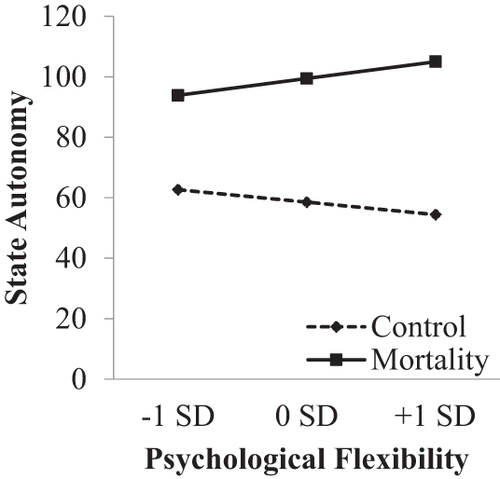

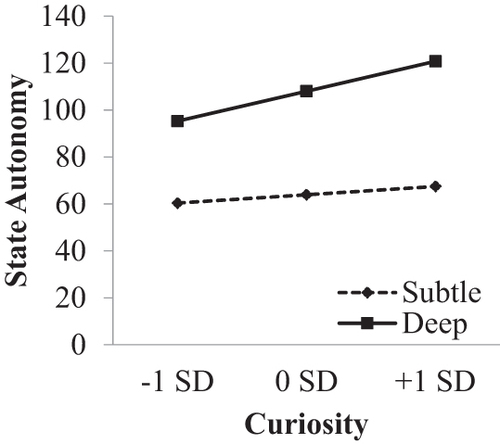

The main effects of the condition variables were non-significant in both steps of each model and there were no significant interactions between either condition variable and trait autonomy. Both psychological flexibility and curiosity were found to moderate the effect of condition on state autonomy, though for curiosity, this effect was only significant in the combined model. Flexibility significantly moderated the effect of being exposed to any mortality cue condition compared to the control task, uniquely accounting for 1.4% of the variance in state autonomy (sr = .12) in the combined model. To clarify the nature of this interaction, tests of simple slopes examined the effect of any mortality cue condition compared to the control for those high and low on psychological flexibility (±1 SD from the mean; see ). Exposure to mortality cues significantly increased state autonomy for individuals high on flexibility; β = .15, t(430) = 2.31, p = .022, CI95%= [1.71, 21.48]; although not for those low on flexibility; β = −.10, t(430) = −1.50, p = .135, CI95%= [−17.45, 2.35]. Psychological flexibility was not found to moderate the relative effects of the two mortality conditions. However, trait curiosity was found to moderate the relative effects of the two mortality conditions in the combined model (see ), uniquely accounting for 0.8% of the variance in state autonomy (sr = .09). Tests of simple slopes revealed that deep mortality cues (as opposed to subtle mortality cues) significantly increased state autonomy for individuals high in curiosity; β = .14, t(430) = 2.21, p = .027, CI95%= [1.46, 24.49]; although not for those low in curiosity; β = −.06, t(430) = −.89, p = .373, CI95%= [−17.27, 6.49]. Curiosity did not moderate the effects of being exposed to any mortality cue condition compared to the control.

Discussion

Among these undergraduates, death awareness did not generally serve as a “wakeup call” (Martin et al., Citation2004, p. 437) to a more autonomous, authentic way of living. However, there was some evidence that death awareness did increase state autonomy for certain individuals, partially supporting hypotheses and highlighting the crucial importance of individual-level characteristics. Contemplating death can increase state autonomy, but not for everyone, just as the posttraumatic growth and meaning-making literature acknowledges that not all individuals exhibit growth in the face of trauma or worldview-threat (Park, Citation2010; Tedeschi & Calhoun, Citation2004).

Notably, trait autonomy did not moderate the effects of death awareness on state autonomy. Testing the moderating role of trait autonomy logically extended past research (Cozzolino et al., Citation2004), and attempted to clarify the direction of this effect, in the context of two plausible yet opposing effect directions based on the literature. However, one potential explanation for the null finding is that both directional pathways are equally valid and statistically counteract each other. That is, trait autonomy may make it less likely that people will need to revise their motivations and grow, while also increasing their ability to revise their motivations and grow when necessary (Joseph & Linley, Citation2005). Future research may consider assessing the moderating role of trait autonomy within other growth responses to death awareness (e.g., seeking new information and experiences). Researchers more broadly interested in the role prior levels of autonomy could consider assessing growth responses to death after priming autonomy (Vail et al., Citation2020). Alternatively, within-person designs could track changes on the same measure of autonomy before and after implementing an extended death awareness manipulation, and subsequently determine whether individuals experiencing (versus not experiencing) growth were initially higher or lower on autonomy.

It appears that greater psychological flexibility may facilitate increased state autonomy following any degree of exposure to mortality (either deep or subtle). This finding is likely due in part to the mindful awareness that forms a substantial component of flexibility, enabling individuals to process subtle mortality cues more consciously and with greater specificity, and therefore similarly to deep mortality cues. In support of this explanation, mindful awareness has been found to increase writing time during a subtle mortality cue manipulation and decrease subsequent suppression of death thoughts (Niemiec et al., Citation2010), suggesting a greater openness to deeply processing mortality. Additionally, the capacity of flexible people to endure uncomfortable experiences may help to maintain focus on specific, individuating aspects of death awareness, and enable them to autonomously guide how these uncomfortable experiences inform their life goals. Therefore, the ostensive depth of mortality cues may not be the only factor involved in how deeply death is processed, as individual-level characteristics like flexibility are also likely to impact depth of processing.

Unlike flexibility, curiosity only facilitated increased state autonomy after deep mortality cues. Highly curious individuals are interested in exploring the unknown, enjoy challenging their understanding of the world and actively seek out these experiences as opportunities for personal development. These qualities would render the conscious and specific exploration of the meaning of their mortality, as provided by the deep mortality cue manipulation task, a valuable opportunity for self-expansion and growth. The subtle mortality cue manipulation task is unlikely to offer quite the same opportunity for curious people, given the more abstract questions and greater dissociation between death thoughts and the assessment of autonomy for personal goals. This evidence, albeit partial, provides some support for arguments that death awareness has differential effects based on the depth of mortality cues (Cozzolino, Citation2006; Vail et al., Citation2012), at least for curious people.

Organismic valuing theory (Joseph & Linley, Citation2005) provides a framework to better understand the underlying processes at play in the moderation effects for both flexibility and curiosity. This perspective suggests that accommodation processes are at play, where, in order to experience growth, flexible and curious individuals do not simply assimilate a threatening event within their preexisting worldview, but make adjustments to their worldview in light of the event. In doing so, they move beyond the avoidance of the threat and become actively engaged in a process of meaning-making, reevaluating their beliefs about how things are relationally connected in their world (Park, Citation2010) and what is of value or significance in their life (Janoff-Bulman & Frantz, Citation1997). Therefore, flexibility and curiosity likely facilitate growth-oriented responses to death awareness, by decreasing avoidance of threatening mortality cues and increasing the ability to accommodate the meaning structures underpinning one’s autonomy.

We note that reported effect sizes were small, perhaps due to the inability of the experimental manipulations to accurately mimic in vivo confrontations with death. The experimental nature of the present study enables causal inferences, although it comes at the cost of ecological validity. It is in combination with quasi-experimental findings that genuine confrontations with mortality relate to greater autonomy (Arena et al., Citation2022) that the present results become more compelling. The age of the current sample may have also reduced the effects of death awareness. It is likely easier for younger people to make use of the proximal defenses described by TMT (Solomon et al., Citation2004), whereby one avoids contemplation of mortality by reassuring oneself that death is a far-removed problem in a distant hypothetical future.

This study intended to compare the types of death awareness theorized to lead to differential outcomes by manipulating the depth of mortality cues; however, a limitation of this approach is that it does not clarify the respective underlying roles of conscious awareness and specificity. It may be that one of these factors is more or entirely responsible for differential effects, although we note that only limited differences were found between deep and subtle mortality cue conditions. The findings of Kosloff and Greenberg (Citation2009) suggest that conscious awareness may be sufficient to explain some differential effects, although these authors also suggest that the specificity of mortality cues may function to maintain conscious attention on mortality. Thus, more tailored research is needed to tease apart the mechanisms responsible for growth responses to death. The deep and subtle mortality cue conditions also differed in other respects. The specific mode of dying described in the deep mortality cue task is improbable and potentially avoidable, in comparison to the general inevitability of death described in the subtle mortality cue task. The deep mortality cue task also makes family salient, feasibly contributing toward state autonomy for intimacy, although family salience is characteristic of the specific way death is contemplated during traumas and NDEs. Further work in this area may benefit from devising manipulations that remove the influence of these factors or can isolate and explore their unique impact.

Autonomy should continue to be studied as a growth response to death awareness, using varied samples and methods that will help to understand the reach and limits of such responses. Very little research has directly assessed this construct in such circumstances and doing so could help determine the extent to which autonomy accounts for many diverse growth outcomes. Furthermore, using motivational indices could help to corroborate retrospective, self-report measures of posttraumatic growth that have been criticized as potentially illusory in nature (e.g., Zoellner & Maercker, Citation2006). The present findings also set the stage for future research to explore other personal characteristics that enhance autonomy in response to death awareness. These may include openness-related constructs like attitudes toward ambiguity (Lauriola et al., Citation2016), or emotion regulation and approach-oriented coping strategies (given their role in facilitating goal pursuits and promoting both flexibility and coherence in personality processes; Koole, Citation2009).

The findings have practical implications regarding pathways to improve the lives of people struggling with traumatic or existential crises. The way people deal with death has been suggested to inform the development and maintenance of a number of psychological disorders (Iverach et al., Citation2014). As such, this research has implications for the treatment of existential distress; notably, that fostering psychological flexibility, and potentially curiosity, may enable growth-oriented responding. One main aim of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) is to increase flexibility, and previous research has found increased flexibility to predict the efficacy of ACT in treating distress associated with terminal illness (Hulbert-Williams et al., Citation2015). The present findings dovetail with this research and provide complementary experimental evidence for the importance of flexibility in dealing with existential concerns. Although we assessed flexibility at the trait level, our findings are consistent with the notion that training flexibility may be a key pathway for improving well-being in people suffering from existential distress. In addition, the present research has implications for death education and death-related self-awareness training for health professionals and counselors (e.g., Smith-Cumberland, Citation2006; Stella, Citation2016), by demonstrating the potential for such practices to have positive motivational consequences. For those working with the seriously ill, injured, or bereaved, increased autonomy is also likely to have positive consequences for the clients they serve, by promoting the prosocial, values-based actions inherent to these professions.

There is no guarantee that individuals will accept the call to pursue an autonomous life described by existentialists when confronting death (Martin et al., Citation2004; May, Citation1950). They may instead choose the less daunting route of avoiding change and the anxiety of abandoning what they know, yet this study identified psychological constructs that may encourage positive growth in the face of death. By seeking to understand factors that enable people to deal with confrontations with death constructively, we can begin to understand how to develop this capacity in others and thereby enrich their lives.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (15.1 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to sincerely thank Dr Carolyn MacCann for her guidance during parts of this project.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available as per the conditions of ethical approval for this study. Participants did not consent to have their anonymous data shared publicly.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arena, A. F. A., MacCann, C., Moreton, S. G., Menzies, R. E., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2022). Living authentically in the face of death: Predictors of autonomous motivation among individuals exposed to chronic mortality cues compared to a matched community sample. OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying, 302228221074160. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228221074160

- Arndt, J., & Greenberg, J. (1999). The effects of a self-esteem boost and mortality salience on responses to boost relevant and irrelevant worldview threats. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 25(11), 1331–1341. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167299259001

- Bond, F. W., Hayes, S. C., Baer, R. A., Carpenter, K. M., Guenole, N., Orcutt, H. K., Waltz, T., & Zettle, R. D. (2011). Preliminary psychometric properties of the Acceptance and Action Questionnaire–II: A revised measure of psychological inflexibility and experiential avoidance. Behavior Therapy, 42(4), 676–688. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.03.007

- Burke, B. L., Martens, A., & Faucher, E. H. (2010). Two decades of terror management theory: A meta-analysis of mortality salience research. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 14(2), 155–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868309352321

- Cohen, J., Cohen, P., West, S. G., & Aiken, L. S. (2003). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). L. Erlbaum Associates.

- Cozzolino, P. J. (2006). Death contemplation, growth, and defense: Converging evidence of dual-existential systems? Psychological Inquiry, 17(4), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/10478400701366944

- Cozzolino, P. J., Staples, A. D., Meyers, L. S., & Samboceti, J. (2004). Greed, death, and values: From terror management to transcendence management theory. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 30(3), 278–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203260716

- Grant, A., & Wade-Benzoni, K. (2009). The hot and cool of death awareness at work: Mortality cues, aging, and self-protective and prosocial motivations. Academy of Management Review, 34(4), 600–622. https://doi.org/10.5465/AMR.2009.44882929

- Greenberg, J., Pyszczynski, T., Solomon, S., Simon, L., & Breus, M. (1994). Role of consciousness and accessibility of death-related thoughts in mortality salience effects. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 627–637. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.627

- Guay, F., Mageau, G. A., & Vallerand, R. J. (2003). On the hierarchical structure of self-determined motivation: A test of top-down, bottom-up, reciprocal, and horizontal effects. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(8), 992–1004. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167203253297

- Iverach, L., Menzies, R. G., & Menzies, R. E. (2014). Death anxiety and its role in psychopathology: Reviewing the status of a transdiagnostic construct. Clinical Psychology Review, 34(7), 580–593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2014.09.002

- Janoff-Bulman, R., & Frantz, C. M. (1997). The impact of trauma on meaning: From meaningless world to meaningful life. In C. Brewin & M. J. Power (Eds.), The transformation of meaning in psychological therapies: Integrating theory and practice. Wiley.

- Joseph, S., & Linley, P. A. (2005). Positive adjustment to threatening events: An organismic valuing theory of growth through adversity. Review of General Psychology, 9(3), 262–280. https://doi.org/10.1037/1089-2680.9.3.262

- Kashdan, T. B., Gallagher, M. W., Silvia, P. J., Winterstein, B. P., Breen, W. E., Terhar, D., & Steger, M. F. (2009). The curiosity and exploration inventory-II: Development, factor structure, and psychometrics. Journal of Research in Personality, 43(6), 987–998. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2009.04.011

- Kernis, M. H., & Goldman, B. M. (2006). A multicomponent conceptualization of authenticity: Theory and research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 38, 283–357. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(06)38006-9

- Koole, S. L. (2009). The psychology of emotion regulation: An integrative review. Cognition & Emotion, 23(1), 4–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930802619031

- Kosloff, S., & Greenberg, J. (2009). Pearls in the desert: Death reminders provoke immediate derogation of extrinsic goals, but delayed inflation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(1), 197–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2008.08.022

- Lauriola, M., Foschi, R., Mosca, O., & Weller, J. (2016). Attitude toward ambiguity: Empirically robust factors in self-report personality scales. Assessment, 23(3), 353–373. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191115577188

- Martin, L. L., Campbell, W. K., & Henry, C. D. (2004). The roar of awakening: Mortality acknowledgment as a call to authentic living. In J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, & T. A. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 431–448). Guildford Press.

- Martin, L. L., & Kleiber, D. A. (2005). Letting go of the negative: Psychological growth from a close brush with death. Traumatology, 11(4), 221–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/153476560501100403

- May, R. (1950). The meaning of anxiety. Ronald Press Co.

- Niemiec, C. P., Kashdan, T. B., Breen, W. E., Brown, K. W., Cozzolino, P. J., Levesque- Bristol, C., & Ryan, R. M. (2010). Being present in the face of existential threat: The role of trait mindfulness in reducing defensive responses to mortality salience. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(2), 344–365. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019388

- Park, C. L. (2010). Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 257–301. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018301

- Prentice, M., Kasser, T., & Sheldon, K. M. (2018). Openness to experience predicts intrinsic value shifts after deliberating one’s own death. Death Studies, 42(4), 205–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1334016

- Hulbert-Williams, N. J., Storey, L., & Wilson, K. G. (2015). Psychological interventions for patients with cancer: Psychological flexibility and the potential utility of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy. European Journal of Cancer Care, 24(1), 15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecc.12223

- Rosenblatt, A., Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., Pyszczynski, T., & Lyon, D. (1989). Evidence for terror management theory I: The effects of mortality salience on reactions to those who violate or uphold cultural values. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(4), 681–690. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.4.681

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2002). Overview of self-determination theory: An organismic dialectical perspective. In E. L. Deci & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 3–33). University of Rochester Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2004). Autonomy is no illusion: Self-determination theory and the empirical study of authenticity, awareness, and will. In J. Greenberg, S. L. Koole, & T. A. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 455–484). Guilford Press.

- Seto, E., Hicks, J. A., Vess, M., & Geraci, L. (2016). The association between vivid thoughts of death and authenticity. Motivation and Emotion, 40(4), 520–540. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9556-8

- Sheldon, K. M., & Kasser, T. (1998). Pursuing personal goals: Skills enable progress, but not all progress is beneficial. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 24(12), 1319–1331. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672982412006

- Smith-Cumberland, T. (2006). The evaluation of two death education programs for EMTs using the theory of planned behavior. Death Studies, 30(7), 637–647. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180600776028

- Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (2004). The cultural animal: Twenty years of terror management theory and research. In J. Greenberg, S. Koole, & T. Pyszczynski (Eds.), Handbook of experimental existential psychology (pp. 13–34). Guilford Press.

- Stella, M. (2016). Befriending death: A mindfulness-based approach to cultivating self-awareness in counselling students. Death Studies, 40(1), 32–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2015.1056566

- Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

- Vail, K. E., Conti, J. P., Goad, A. N., & Horner, D. E. (2020). Existential threat fuels worldview defense, but not after priming autonomy orientation. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 42(3), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2020.1726747

- Vail, K. E., Juhl, J., Arndt, J., Vess, M., Routledge, C., & Rutjens, B. T. (2012). When death is good for life: considering the positive trajectories of terror management. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 16(4), 303–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868312440046

- Vallerand, R. J., & Blssonnette, R. (1992). Intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivational styles as predictors of behavior: A prospective study. Journal of Personality, 60(3), 599–620. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00922.x

- Yalom, I. D. (1980). Existential psychotherapy. Basic Books.

- Zoellner, T., & Maercker, A. (2006). Posttraumatic growth in clinical psychology—A critical review and introduction of a two component model. Clinical Psychology Review, 26(5), 626–653. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.01.008