Abstract

Understanding mental health professionals’ (MHPs) willingness to treat suicidal older adults is critical in preventative psychotherapy. We examined the effect of a hypothetical patient’s age and suicide severity on MHPs’ willingness to treat or refer them to another therapist. Vignettes of hypothetical patients were presented to 368 MHPs aged 24-72 years. The vignettes had two age conditions (young/old) and three suicidality severity conditions. MHPs completed measures of their levels of willingness to treat/likeliness to refer and their levels of ageism. As suicide severity intensified, MHPs were less willing to treat and more likely to refer. Willingness to treat was the lowest for the old/suicide attempt condition. Ageism moderated the relationships between patient age and willingness to treat: MHPs with higher ageism were less willing to treat older than younger patients, regardless of suicidality severity. Findings indicate that MHPs with higher ageism levels are more reluctant to treat older suicidal patients and highlight the need for training MHPs to reduce ageism and enhance competence in suicide interventions.

Introduction

Every 40 seconds, someone dies by suicide globally (World Health Organization, Citation2019), placing suicide as one of the leading causes of death worldwide. People aged 70 years and over have the highest suicide rate in most countries (Israel Ministry of Health, Citation2020; Obuobi-Donkor et al., Citation2021; World Health Organization, Citation2019). In Israel, the suicide rates are lower than those common in the Western world (6.5 per 100,000 people in Israel compared with 11.7 per 100,000 globally; Israel Ministry of Health, Citation2020). A quarter (n = 500) of all suicide cases each year are of individuals aged 65 and above, with the suicide rate among older adults reaching 21.4 per 100,000, four times the national suicide rate. Considering that the older adult population is projected to increase dramatically in the world (Zeppegno et al., Citation2018) and in Israel (Dwolatzky et al., Citation2017) and that each suicide is a tragic loss that affects many other individuals (e.g., Levi-Belz & Feigelman, Citation2022), these numbers reflect the urgency of improving our ability to prevent suicides among older adults.

To effectively address suicide issues among the elderly population, a comprehensive understanding of the underlying risk factors is imperative. The main known risk factors for older adults’ suicides include becoming a widow/widower, having other mental health disorders, physical illness, and bereavement (Conejero et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, depression and hopelessness were also found to be crucial factors in suicidal risk for this age group (Hernandez et al., Citation2021). Importantly, recent systematic reviews have emphasized the value of early treatment of depression as one of the major effective steps for preventing future suicide (Mann et al., Citation2021; Zalsman et al., Citation2016). Thus, mental health professionals’ (MHPs) willingness to treat older suicidal patients is crucial, as it can comprise a critical “gate” to treatment and ultimately to suicide prevention.

Treating a suicidal patient requires pitting oneself against extreme emotional states, emotional regulation, attentiveness, and discourse that range from emotional pain to acceptance (Jobes, Citation2016). Treating suicidal patients also affect MHPs in many ways, such as arousing negative feelings toward the patient (Maltsberger & Buie, Citation1974), and can also evoke distressing feelings in the therapist, such as anxiety, panic, and doubts about their professional competence (Reeves & Mintz, Citation2001). Notably, more than 60% of therapists who have experienced patients’ death by suicide reported an impairment in their self-competence and changes in how they conduct therapy (Menninger, Citation1991).

Recent studies have demonstrated that MHPs were less willing to treat a suicidal patient than a depressive patient with no suicidal behaviors (e.g., Almaliah‐Rauscher et al., Citation2020; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020). Moreover, most MHPs in these studies who read a vignette of suicidal potential patients were more likely to refer them to another MHP, with the likelihood of referring a depressive patient being much lower. A possible explanation for those findings could be related to some MHPs’ lack of competence in providing effective treatment for suicidal patients (Shiles, Citation2009). An alternate explanation acknowledges the MHPs’ dread of the suicide risk that accompanies treating suicidal patients. Indeed, for most MHPs, the most dreaded treatment outcome is the patient’s death by suicide (Pope & Tabachnick, Citation1993). Importantly however, these cited studies did not examine the possible effects of the hypothetical patient’s age on willingness to treat, thus leaving open the question of to what extent MHPs are prepared to treat older adult patients with or without suicidal ideation and behavior.

Surprisingly, almost no studies have examined MHPs’ willingness to treat, focusing on older suicidal patients. What is known about treating this age group is that MHPs experience a wide range of specific difficulties, such as reluctance and low motivation to accept an older adult for treatment (Bodner et al., Citation2018). Helmes and Gee (Citation2003) found that MHPs ranked an older potential patient as “less able to develop an adequate therapeutic relationship, to have a poorer prognosis, and to be less appropriate for therapy” (p. 663). Specific to the present study, psychiatrists were found to be less interested in treating an older suicidal patient than a young one because they perceived the suicidal tendencies in older adults as logical and normal (Bodner et al., Citation2018). This inclination to avoid accepting older people for therapy or underestimate their suffering may be due to negative perceptions regarding older individuals, termed ageism.

Ageism was defined by Butler (Citation1975) as “a process of systematic stereotyping and discrimination against people because they are old” (p. 12); ageism is most common in Western countries, but its prevalence is worldwide (McConatha et al., Citation2003). Ageism can be measured explicitly (reflecting thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward older adults) or implicitly (supposedly reflecting unconscious thoughts, feelings, and behaviors toward older adults; Hofmeister-Tóth et al., Citation2021). Terror management theory (Greenberg et al., Citation1997) offers a theoretical framework for understanding the occurrence of ageism, positing that older individuals may evoke existential anxieties related to mortality among younger individuals (Martens et al., Citation2005). Consequently, the ensuing defensive responses can manifest as ageist attitudes and behaviors.

Ageism can appear and be expressed in various ways. For example, an ageistic perspective would consider depression as a normative feature of the aging process and having to endure conditions of physical illnesses and disabilities, life events and losses may be viewed by some as legitimate justifications for suicide (De Leo, Citation2018). Furthermore, it has been found that the more a person holds ageist perceptions, the more permissive they are regarding elderly suicide (Gamliel & Levi-Belz, Citation2016). Another study examined the prevalence of clinical bias toward older adults among clinical psychology practitioners (Pyne, Citation2020). The results showed that practitioners displayed a substantial clinical bias toward elderly patients, suggesting that explicit ageism plays an important role in the differential treatment of older clients. Furthermore, whereas one can expect ageism to lessen in the wake of more clinical experience and exposure, Punchik et al. (Citation2021) showed that with extensive experience and numerous patients, ageist attitudes among practitioners were stronger. Interestingly, no studies have examined the moderating role of ageism on practitioners’ willingness to treat older adults.

The present study

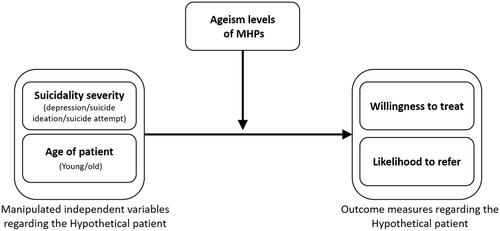

This study sought to narrow the gap in knowledge regarding factors affecting MHPs’ willingness to treat suicidal older adults. Thus, we examined MHPs’ willingness to treat and the likelihood of their referring out suicidal patients in their outpatient office setting. Given older adults’ high suicide rates (World Health Organization, Citation2019) and that older adults in Israel account for about a quarter of all suicides (Israel Ministry of Health, Citation2020), we examined the effect of patient age on the MHPs’ willingness to treat the patient, with the moderation of ageism levels in these associations. As seen in , based on previous research with similar methodology (e.g., Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020), the current experimental study presented participants with vignettes of a case study of a hypothetical patient portrayed with three alternative suicidality conditions: depressive symptoms, active suicide ideation (SI), or a recent suicide attempt (SA). Importantly, however, we took the previous studies a step forward by examining the effect of hypothetical patient age, presenting two age conditions: the hypothetical patient as young (29 years old) or old (74 years old).

After the MPH participants read the relevant vignettes, they responded to several questions concerning the hypothetical case, focusing on their willingness to treat or their inclination to refer the patient to another clinician. We also added a novel examination of the MHPs’ ageism to explore its potential moderating role in the noted effects of suicide severity and age on willingness to treat/likelihood to refer. Four hypotheses were examined:

As the hypothetical patient’s suicidality level intensifies, the MPH will be less willing to treat that person and more likely to refer the patient to another provider.

The hypothetical patient’s age will affect the willingness of MHPs to treat: The MHPs will be less willing to treat an older patient and more likely to refer the patient to another provider.

The combined effects of age and suicide severity levels on the MHPs’ willingness to treat and their likelihood to refer will be higher than of each factor alone: Thus, the least willingness to treat and highest likelihood to refer will be found in the old/high suicidality condition.

The MHPs’ ageism levels will moderate the effects of age and suicide severity conditions on willingness to treat and likelihood to refer.

Methods

Participants

The survey was completed by 369 MHPs in Israel who work in the private and public sectors. One participant did not fully complete the questionnaires, leaving a final study sample of 368 participants. As presented in , the sample comprised 64 males and 304 females aged 21-72 (Mage = 35; SD = 9.12). Regarding professional characteristics, most (n = 205) were trained psychologists, 59 were social workers, and the remainder (n = 104) were art therapists, clinical criminologists, psychiatrists, and other therapist types, such as movement therapists. The participants’ professional seniority averaged six years (SD = 7.44), ranging from a few months to 45 years. The MHPs’ workplace was either public (54%), private (23%), or combined (23%). In addition, 19.8% of the MHPs had previous professional acquaintance with patients who died by suicide, and 19.5% had professional experience with older adult patients.

Table 1. Demographic and professional characteristics of the sample (N = 368).

Procedure

Approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Ruppin Academic Center, which has previously approved different studies employing similar research designs. The research study was electronically distributed in April-June 2022, using the Qualtrics platform, an online survey tool that incorporates measures to identify and prevent duplicate responses. An Internet link to the questionnaire was distributed using snowball sample recruitment and shared in closed social media groups subscribed solely by mental health professionals. The study was described to participants as focusing on mental health and their perceptions of patients with different levels of mental pain. Moreover, it was explained that the study contained a short textual hypothetical case study followed by several questions. Informed consent was obtained after explaining the research procedure, and the consenting individuals were randomly assigned to one of the study’s six case conditions. After reading the assigned vignette, the participants were requested to complete the self-report questionnaires.

Measures

Each participant received a single textual case vignette out of the six conditions (a three [suicidality severity] x two [patient age] design) along with an ageism measure and a demographic and clinical/training information questionnaire to be described.

Demographics, clinical training, and practice characteristics

Demographic and clinical practice and training information were collected, including gender, age, years of professional seniority, general experience, experience with older patients, and professional training in suicide prevention (including suicide prevention training regarding suicide risk assessment [minimum four hours] or suicide risk assessment and suicide intervention [minimum 12 hours] operated by the Ministry of Health). The data derived from the measures are presented in .

Experimental manipulation of the suicidality level

As a manipulation check, we assessed the perceived severity of suicidality of the hypothetical patient with two questions (e.g., ‘To what extent do you think the patient is at risk for suicide?'), presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale (higher scores indicating higher risk). A positive significant Pearson correlation was found between the two items, r(368) = .91, p < .001. Consequently, both items were combined into a single measure of the severity of suicidality. Thus, this measure was used as an index to reflect the severity of the hypothetical patient’s suicidality.

Willingness to treat and likelihood to refer

Scales for assessing the degree to which the MHP would be willing to accept the hypothetical patient for treatment and the likelihood of referring him to another clinician were designed for this study. Importantly, despite some overlap between these two outcome variables, using both measures provides a wider portrayal of MHPs’ perceptions of the hypothetical patient. Unwillingness to treat represents a more active and radical position, whereas likelihood to refer a patient represents a more subtle refusal to treat. We chose to examine both outcome measures.

To construct reliable and valid questions to examine these concerns, questions resembling those from previous studies (Hunter, Citation2015; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020; Norheim et al., Citation2013; Samuelsson & Åsberg, Citation2002; Uncapher & Areán, Citation2000) were adapted for the current study. Four items were formulated assessing the degree of willingness to treat (e.g., “To what extent are you willing to treat this patient?”; “If a colleague were to call you and describe this patient’s case, how would you rate your willingness to treat him?”). The items were presented on a 7-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very low chances) through 4 (moderate chances) to 7 (very high chances). The four items were combined into an index of willingness to treat, with the resulting index in the current sample found to have good reliability (Cronbach’s α = .91).

The measure of the likelihood of referring the patient out comprised a single item, rated on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging from 1 (very low chances), through 4 (moderate chances), to 7 (very high chances). The item concerned the likelihood that the participant would refer the patient to another mental health practitioner.

Ageism

Ageism levels of the MHPs were assessed using the Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA; Fraboni et al., Citation1990), which measures ageist attitudes and beliefs toward older adults (e.g., “A lot of older people tend to hoard their money and property”). We used the 18-item Hebrew version, presented on a 6-point Likert-type scale, ranging between 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree). The short version aimed to include only the specific items that align with Israeli society and culture (Bodner & Lazar, Citation2008). The FSA comprises three subscales: contribution ability of older adults (α for current sample = .50), avoidance of older adults (α for current sample = .56), and stereotyped beliefs toward older adults (α for current sample = .72). Previous reliability parameters on this scale ranged from .60 to .80 (Bodner et al., Citation2012).

The vignettes

The decision to use vignettes to examine willingness to treat among MHPs stemmed from its advantages concerning ecological validity and the ability to manipulate specific conditions. All six conditions presented identical crisis background stories and descriptions. The vignette’s story describes a hypothetical male patient experiencing a personal crisis and is referred for treatment. Male gender and personal crisis are two risk factors that suggest an authentic patient seeking treatment due to depression or suicidal urges. Moreover, in all the stories, the hypothetical patient is described as having experienced several traumatic events (e.g., the death of his mother at the age of 9), contributing to the patient’s credibility that he is suffering from mental pain and is seeking treatment.

Different vignettes described the young vs. the older patient, as their ages dictated a need to vary their background. For example, we described the older patient as a widow, as this is a factor recognized as a risk factor for suicide among older adults. Accordingly, the young patient was described as single, a recognized risk factor for suicide among younger adults. However, we maintained identical events and psychological states in the two age conditions. The narrative presented below was constructed based on past suicide-related studies using similar methodologies (Bresin et al., Citation2013; Gamliel & Levi-Belz, Citation2016; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020) to underpin the validity of the current study’s vignettes:

The background story of the young hypothetical patient:

Ronen is a 29-year-old single man with no children and lives alone. In the last few days, he has been seeking psychological treatment. This is his story. Ronen is an only child. His mother died of cancer when he was ten; he remained with his father after her death. After graduation, he moved to the center of the country due to work. After 5 years in his job, his manager informed him he was fired. Over the last two years, Ronen has been in a romantic relationship, which he saw as a long-term commitment. Yet, about a month ago, after a prolonged period of disagreements, his girlfriend informed him that she did not feel she loved him anymore, and they broke up. In recent weeks, he has found himself reviewing events from the relationship over and over again, trying to analyze what caused the breakup. He finds it difficult to persevere in the job search and is very fearful of the future. He truly believes there is no chance he will find love again.

Ronen is a 74-year-old man, a widower with no children, who lives alone. In the last few days, he has been seeking psychological treatment. This is his story. Ronen is the father of three children, two of whom live abroad. Ronen’s wife died about five years ago of cancer. He lives alone in a small apartment. He retired about six years ago, and since then, he has participated in some of the activities of the senior citizen center in his city. The last two years have seen a deterioration in his health, including a decline in his ability to manage independently. He has suffered from repeated joint pains. He has consulted several physicians and has undergone many tests but has yet to receive a formal diagnosis for his condition. About a month ago, he fell in the shower and injured his pelvis. Since then, he has had difficulty in his daily functioning and has experienced concerns about entering a nursing facility. He is also anxious about the prospect of being unable to provide sufficient financial assistance to his children due to the cost of his medical treatments.

After participants read their respective randomly assigned narrative, the virtual hypothetical patient’s suicidality condition (depression, suicide ideation, or suicide attempt) was presented.

Depression condition

The hypothetical patient’s depressive condition presented depressive symptoms resulting from the patient’s psychological crisis. Items from the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., Citation1988) were incorporated into the case study to construct a credible picture of a person suffering from a depressive episode:

In the last month, Ronen has felt great sadness and despair about his future. He cries a lot, feels worthless, and even experiences himself as a failure, adding to his self-disappointment. He doesn’t enjoy meeting friends as he used to, has trouble concentrating when reading books and newspapers, and feels fatigued and constantly lacking energy. In addition, Ronen does not sleep well at night. Some nights he wakes up multiple times and has a hard time getting back to sleep, and, consequently, finds himself making up hours of sleep during the day. His appetite has decreased, and he has lost weight. These events led to Ronan’s request to receive treatment from you.

Suicide ideation (SI) condition

The hypothetical patient’s suicide ideation condition presented depressive symptoms and active suicide ideation due to the identical crisis. This description was constructed based on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., Citation2011), designed to diagnose the severity of a person’s suicide risk according to his behavior and the actual presenting symptoms. C-SSRS items were incorporated in the vignette to construct a realistic case study of the most accurate situation of a person suffering from a crisis and presenting active suicidal ideation along with a suicide method:

Ronen has suicidal thoughts - he expresses a desire to die by suicide. He has a suicide method but no concrete plan for execution. These thoughts disturb him several times during the day, and he has difficulty stopping them. These events led to Ronen’s request to receive treatment from you.

Suicide attempt (SA) condition

The hypothetical patient’s suicide attempt condition presented suicide risk with a suicide attempt in the previous days. This description was constructed based on the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS; Posner et al., Citation2011), designed to diagnose the severity of a person’s high suicide risk according to his behavior and the actual presenting symptoms. C-SSRS items were selected to construct a realistic case study to portray the most accurate situation of a person suffering from a crisis and presenting active suicidal ideation and a suicide attempt:

Three weeks ago, Ronen attempted suicide. He took a large number of pills before going to sleep. He woke up the next day, was checked into the emergency room and released after two days. These events led to Ronen’s request to receive treatment from you.

Data analysis

The independent variables of the hypothetical patient’s suicidality severity (depression/SI/SA) and age group (young/old) were manipulated, resulting in a 2 × 3 design. Each participant was randomly assigned to one of the six experimental conditions (61 participants in each group). Other independent variables included professional experience and training in suicide prevention as well as ageism levels. The two dependent variables were willingness to treat and likeliness to refer. Analyses were performed using SPSS Version 23.

First, we computed descriptive statistics of demographic and questionnaire data. Second, the associations between the study variables were examined with a series of Pearson correlation analyses. Third, we conducted a manipulation check to examine the difference in rating the hypothetical patient’s suicidality severity. Fourth, the effects of suicidality and age on the likelihood of treating or referring the hypothetical patients were explored using a two-way MANOVA. Finally, to examine our moderation hypotheses, a moderation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro in SPSS (Hayes, Citation2013, Model 2). We evaluated the significance of interaction effects with a “pick-a-point” approach for probing moderation effects. This approach involves selecting representative moderator values (e.g., low = 1SD below the mean, moderate = sample mean, and high = 1SD above the mean) and then estimating the effect of the focal predictor at those values (Hayes & Matthes, Citation2009). These analyses facilitated our understanding of the specific role of each personal characteristic in the link between ageism and the MHPs’ willingness to treat the hypothetical patient.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the outcome measures and ageism factors are presented in . The average level of willingness to treat was 4.81 (SD = 1.40) on a scale of 1-7, representing moderate-high willingness. Interestingly, the levels of likelihood to refer were somewhat higher (M = 4.98, SD = 1.11), representing a moderate-high inclination to refer the patient out. Overall, the participants reported low ageism levels, with the average scores on all three dimensions ranging from 2.2–2.7 on a scale of 1-6. As the study randomized participants to the six vignette groups, no significant differences were found between the groups in demographics or agism levels.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of study variables (N = 368).

Manipulation check

To determine whether the referred patient descriptions adequately distinguished between the suicidality conditions, we examined the difference in the rating of the suicide risk severity of the hypothetical patient as perceived by the MHPs using a one-way ANOVA analysis. Significant differences were found between the groups, F(2,366) = 172.81, p < .001. MHPs who read the hypothetical SA patient’s vignette rated the patient as having a higher suicidal risk (M = 6.28, SD = 0.9) than MHPs who read the hypothetical SI patient’s vignette (M = 5.12, SD = 0.92) and those receiving the hypothetical depressive patient’s vignette (M = 3.88, SD = 1.23).

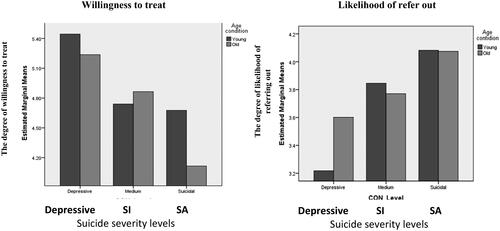

Willingness to treat and likeliness to refer

To examine the differences in willingness to treat and likeliness to refer as a function of the suicidality severity condition (depressive/SI/SA) and patient’s age (young/old), we conducted a two-way MANOVA. Years of experience served as a covariate variable. A significant multivariance effect was found in the suicidality severity condition, F(4,722) = 7.76, p < .001, partial ƞ2 = .041. As seen in , MHPs who read the SA patient’s condition reported the lowest willingness to treat (M = 4.39, SD = 1.47) relative to the SI patient (M = 4.80 SD = 1.35) and the depressive patient (M = 5.35, SD = 1.19). Furthermore, MHPs who read the SA condition reported the highest inclination to refer the patient to another clinician (M = 4.07, SD = 1.56), relative to those who read the SI condition (M = 3.81, SD = 1.52) and the depressive condition (M = 3.40, SD = 1.42). No differences were found for the hypothetical patient’s age (young/old) regarding the willingness to treat and likeliness to refer inclinations. We also examined the combined contribution of suicidality and patient age condition on willingness to treat and likeliness to refer. As seen in , we found that in the SA condition, MHPs reported significantly lower willingness to treat levels for old relative to young patients, F = 4.92, p = .03, partial ƞ2 = .04.

Relationships between ageism and MHPs’ willingness to treat and likeliness to refer

To examine the hypothesis regarding the role of ageism in the willingness to treat and likeliness to refer options, intercorrelations between the study conditions, ageism dimensions, and outcome measures were calculated. The matrix in shows that ageism stereotypes were negatively correlated with willingness to treat and positively correlated with likeliness to refer.

Table 3. Intercorrelations between the study variables and outcome measures of willingness-to-treat and likely-to-refer (N = 368).

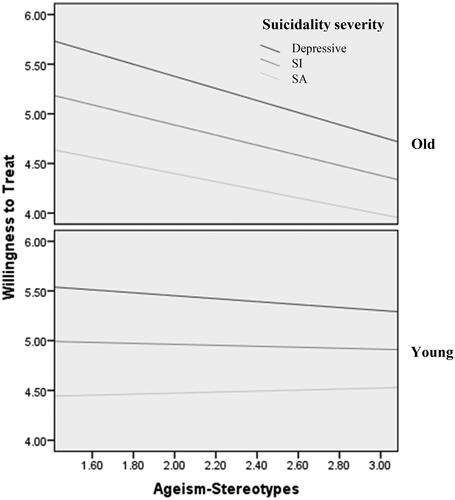

MHPs’ ageism as a moderator of willingness to treat

Following the hierarchical regression results, we employed moderation analyses of significant interactions using the PROCESS macro (Hayes, Citation2013), with willingness to treat as the dependent variable, the hypothetical patient’s age (young/old) and his suicide severity as independent variables, and MHPs ageism stereotype levels as a moderator. To control for previous experience, which could confound the analysis, we entered participants’ years of experience as a therapist as a covariate. As seen in , we found a significant interaction between the two age conditions: In the young-patient condition, ageism stereotype moderated the effect of suicidality levels on willingness to treat; however, in the older-patient condition, we found significant relationships between ageism stereotypes and willingness to treat in all three suicidality conditions (b = −0.46, SE = 0.22, 95% CI [-0.88, −0.04], t(362) = −2.14, p < .03). Thus, while ageism stereotype was not associated with willingness to treat in any of the suicidality severity levels in the young-patient condition, ageism and willingness to treat were significantly correlated in the older-patient condition. Probing the interaction revealed that higher ageistic stereotype beliefs among the MHPs significantly lowered their willingness to treat the older patient in all three suicidality conditions: in the depression condition [b = −0.61, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [-1.01, −0.21], t(362) = −2.97, p < .001], in the SI condition [b =- 0.51, SE = 0.16, 95% CI [-0.82, −0.20], t(362) = −3.23, p < .001] and in the SA condition [b = −0.41, SE = 0.20, 95% CI [-0.81, −0.01], t(362) = −1.99, p < .05].

Discussion

Relative to all life stages, the older adult population presents the highest suicide rate worldwide and in Israel. As treating depression is one of the main strategies to reduce the suicide rate, understanding the factors that may help MHPs increase their willingness to treat older suicidal patients becomes critical. Thus, the main purpose of this study was to shed light on the willingness of MHPs to treat older suicidal patients and its moderating factors. To our knowledge, this is the first study to specifically examine the willingness to treat suicidal older adults in a large MHP sample.

Our findings demonstrate that MHPs who read a vignette of a potentially suicidal patient (with SI or SA) reported a lower willingness to treat and a higher likelihood of referring the patient to another MHP than those reading a depressive patient’s vignette. This finding aligns with previous studies (Almaliah‐Rauscher et al., Citation2020; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2020), highlighting the role of the suicidality factor in MHPs’ decision to accept a patient for psychological treatment. Together, these findings underscore the importance of administering training programs to enhance MHPs’ self-competence and confidence in treating suicidal patients. Such programs have been found helpful in improving MHPs’ willingness to treat suicidal patients (Dexter-Mazza & Freeman, Citation2003; Neimeyer et al., Citation2001; Samuelsson & Åsberg, Citation2002).

Regarding the role of the patient’s age in willingness to treat, we did not observe an effect for the age condition, as MHPs’ willingness to treat/likelihood to refer were unaffected by the hypothetical patient’s age. Importantly, however, we found an interaction between suicidality levels and age, as MHPs were less willing to treat the older suicidal patient than the young suicidal patient. This interaction can be understood as multiple intersectional discrimination (Crenshaw, Citation1991; Doron et al., Citation2018), which asserts that older suicidal patients are at double risk for discrimination due to their higher suicide risk and their old age. Previous studies on intersectionality in aging have mostly examined the combination of age and gender (e.g., Hochreiter, Citation2014; Stavrevska & Smith, Citation2020; Warner & Brown, Citation2011). Thus, going beyond previous studies, the present study introduces a novel combination of potential discrimination incorporating age and severity of suicidality, showing that ageism levels generally and the ageism stereotype dimension specifically have a moderating role in the willingness to treat older adults.

Specifically, we found that MHPs with higher levels of ageism reported a significantly lower willingness to treat an older patient than a young patient, regardless of the patient’s suicidality severity. This finding aligns with a previous work (Bodner et al., Citation2018) highlighting that ageist attitudes may cause cognitive distortion toward older adults, such as downplaying assessment of suicidality risk for older patients, as depression is viewed as a normative condition in old age (thus, minimizing the need for intervention and treatment). Ageist attitudes may lead to ageist behavior, which, in our context, implies a reluctance to accept older, potentially suicidal patients to therapy. Bodner et al. (Citation2012) showed that men tend to engage in more avoidance of older adults than women. Our sample being mostly female may account for the lack of contribution of avoidance within the ageism measure. These findings suggest that ageism can play a critical role in therapists’ willingness to treat a potential patient and the likelihood of their referring the patient to another MHP, especially in the private clinical field, where patient selection is more common.

Several limitations of this study warrant mention. While the research measures MHPs’ behavioral intentions toward potential patients, the self-report methodology may be biased by factors such as social rationality, expectations and high moral standards, shame, and a desire to project a moral and professional self-image. Second, the measured intentions may not fully reflect MHPs’ actual behavior toward patients regarding their acceptance or rejection of treatment in the clinics. Future research can investigate actual MHP treatment acceptance rates for suicidal patients and compare them with their corresponding behavioral intentions.

An additional limitation relates to the participants’ demographic data. Specifically, the research focused on collecting information regarding age, gender, and professional experience, whereas variables such as religion, culture, marital status, geographic location, and others were not considered. Exploring these additional variables in future research endeavors could provide further insight into the attitudes of MHPs. For instance, it is plausible to anticipate that religiously observant Jews may exhibit fewer permissive attitudes toward suicide due to the injunction against suicide in Jewish law (Gearing & Lizardi, Citation2009). Another limitation of the study relates to the MHPs’ clinical training. Professional history, such as experience with older patients or other relevant training, may have affected the results. Our assumption was that more experience would lead to greater self-competence in treating older patients. However, sometimes clinicians’ experience can work in the opposite direction, such as when previous therapy ended in a patient’s suicide (Punchik et al., Citation2021). Thus, previous experience can positively or negatively affect self-competence and willingness to treat. It would be valuable to investigate if MHPs who participated in clinical training for suicide prevention would differ from non-trainees in their behavioral intentions regarding suicidal patients. Whereas suicidality prevention training programs may affect behavioral intentions, they may not necessarily impact actual behavior in the same way. Future studies should examine the effect of training programs on self-competence and behavioral intentions to treat older suicidal patients by considering the nature and duration of the training program. This could help determine what training format in the clinical field should be promoted to prevent older adult suicides.

These limitations notwithstanding, our study provides important empirical evidence that a patient’s age and suicidality severity can affect MHPs’ willingness to treat a potential patient. Furthermore, ageism strongly affected the MHPs’ willingness to treat a patient beyond the effect of suicidality severity. These findings raise important implications for clinical practice. Given the high prevalence of suicide in the elderly population and recognizing that we live in an aging society, raising ageism awareness among MHPs is critical. An outgrowth of awareness could lead to developing programs (e.g., Nemiroff, Citation2022) to mitigate ageism stereotypes and facilitate a greater openness and inclination to treat older suicidal adults. The results of this study should encourage health departments to mandate training for ageism among MHPs where disparities and discrimination against older adults are documented in clinical practice generally and in suicide prevention specifically. We believe such training can improve MHPs’ views regarding treating suicidal old patients and thus be an important step toward diminishing the high suicide rate among older adults globally and in Israel.

For the patients, sensitivity to signs of rejection and feelings of burdening the therapist can become more palpable upon encountering a therapist with a low willingness to treat, especially for suicidal patients that may have inherent feelings of isolation and lack of belonging (Gvion & Levi-Belz, Citation2018; Levi-Belz et al., Citation2014). The present findings provide theoretical and practical support for the recognition that therapists who work with suicidal patients must acknowledge and manage negative feelings toward their patients; thus, fostering therapists’ self-awareness should be an important component of any suicide prevention training for professionals. Future research should examine other moderating factors, such as professional confidence, that may affect MHPs’ treatment decisions and explore effective training programs for suicide prevention and interventions to decrease ageism. Examining these factors more deeply may help improve MHPs’ behavioral intentions and actual behaviors relating to treating older suicidal patients so that more lives can be saved.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Almaliah‐Rauscher, S., Ettinger, N., Levi‐Belz, Y., & Gvion, Y. (2020). “Will you treat me? I'm suicidal!” The effect of patient gender, suicidal severity, and therapist characteristics on the therapist’s likelihood to treat a hypothetical suicidal patient. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 27(3), 278–287. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2426

- Beck, A. T., Steer, R. A., & Carbin, M. G. (1988). Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clinical Psychology Review, 8(1), 77–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(88)90050-5

- Bodner, E., & Lazar, A. (2008). Ageism among Israeli students: structure and demographic influences. International Psychogeriatrics, 20(5), 1046–1058. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610208007151

- Bodner, E., Bergman, Y. S., & Cohen-Fridel, S. (2012). Different dimensions of ageist attitudes among men and women: A multigenerational perspective. International Psychogeriatrics, 24(6), 895–901. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610211002936

- Bodner, E., Palgi, Y., & Wyman, M. F. (2018). Ageism in mental health assessment and treatment of older adults. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (vol. 19, pp. 241–262). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_15

- Bresin, K., Sand, E., & Gordon, K. H. (2013). Non-suicidal self-injury from the observer’s perspective: A vignette study. Archives of Suicide Research, 17(3), 185–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.805636

- Butler, R. N. (1975). Why survive? Being old in America. Harper & Row.

- Conejero, I., Olié, E., Courtet, P., & Calati, R. (2018). Suicide in older adults: current perspectives. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 13, 691–699. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S130670

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 43(6), 1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

- De Leo, D. (2018). Ageism and suicide prevention. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 5(3), 192–193. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30472-8

- Dexter-Mazza, E. T., & Freeman, K. A. (2003). Graduate training and the treatment of suicidal clients: The students’ perspective. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 33(2), 211–218. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.33.2.211.22769

- Doron, I. I., Numhauser-Henning, A., Spanier, B., Georgantzi, N., & Mantovani, E. (2018). Ageism and anti-ageism in the legal system: A review of key themes. In L. Ayalon & C. Tesch-Römer (Eds.), Contemporary perspectives on ageism (vol. 19, pp. 303–319), Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-73820-8_19

- Dwolatzky, T., Brodsky, J., Azaiza, F., Clarfield, A. M., Jacobs, J. M., & Litwin, H. (2017). Coming of age: Health-care challenges of an ageing population in Israel. Lancet (London, England), 389(10088), 2542–2550. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30789-4

- Fraboni, M., Saltstone, R., & Hughes, S. (1990). The Fraboni Scale of Ageism (FSA): An attempt at a more precise measure of ageism. Canadian Journal on Aging / La Revue Canadienne du Vieillissement, 9(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980800016093

- Gamliel, E., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2016). To end life or to save life: Ageism moderates the effect of message framing on attitudes towards older adults’ suicide. International Psychogeriatrics, 28(8), 1383–1390. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610216000636

- Gearing, R. E., & Lizardi, D. (2009). Religion and suicide. Journal of Religion and Health, 48(3), 332–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-008-9181-2

- Greenberg, J., Solomon, S., & Pyszczynski, T. (1997). Terror management theory of self-esteem and cultural worldviews: Empirical assessments and conceptual refinements. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 29, 61–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(08)60016-7

- Gvion, Y., & Levi-Belz, Y. (2018). Serious suicide attempts: Systematic review of psychological risk factors. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9, 56. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00056

- Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

- Hayes, A. F., & Matthes, J. (2009). Computational procedures for probing interactions in OLS and logistic regression: SPSS and SAS implementations. Behavior Research Methods, 41(3), 924–936. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.3.924

- Helmes, E., & Gee, S. (2003). Attitudes of Australian therapists toward older clients: Educational and training imperatives. Educational Gerontology, 29(8), 657–670. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270390225640

- Hernandez, S. C., Overholser, J. C., Philips, K. L., Lavacot, J., & Stockmeier, C. A. (2021). Suicide among older adults: Interactions among key risk factors. International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine, 56(6), 408–421. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217420982387

- Hochreiter, S. (2014). Race, class, gender? Intersectionality troubles. Journal of Research in Gender Studies, 4(2), 401–408.

- Hofmeister-Tóth, Á., Neulinger, Á., & Debreceni, J. (2021). Measuring discrimination against older people applying the Fraboni Scale of Ageism. Information, 12(11), 458. https://doi.org/10.3390/info12110458

- Hunter, N. (2015). Clinical trainees’ personal history of suicidality and the effects on attitudes towards suicidal patients. The New School Psychology Bulletin, 13(1), 38–46.

- Israel Ministry of Health. (2020). Suicidality in Israel. https://www.health.gov.il/English/News_and_Events/Spokespersons_Messages/Pages/09082020_01.aspx

- Jobes, D. A. (2016). Managing suicidal risk: A collaborative approach. Guilford Publications.

- Levi-Belz, Y., & Feigelman, W. (2022). Pulling together-The protective role of belongingness for depression, suicidal ideation and behavior among suicide-bereaved individuals. Crisis, 43(4), 278–288. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910/a000784

- Levi-Belz, Y., Barzilay, S., Levy, D., & David, O. (2020). To treat or not to treat: The effect of hypothetical patients’ suicidal severity on therapists’ willingness to treat. Archives of Suicide Research : official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 24(3), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1632233

- Levi-Belz, Y., Gvion, Y., Horesh, N., Fischel, T., Treves, I., Or, E., Stein-Reisner, O., Weiser, M., Shem David, H., & Apter, A. (2014). Mental pain, communication difficulties, and medically serious suicide attempts: A case-control study. Archives of Suicide Research, 18(1), 74–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2013.809041

- Maltsberger, J. T., & Buie, D. H. (1974). Countertransference hate in the treatment of suicidal patients. Archives of General Psychiatry, 30(5), 625–633. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1974.01760110049005

- Mann, J. J., Michel, C. A., & Auerbach, R. P. (2021). Improving suicide prevention through evidence-based strategies: a systematic review. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 178(7), 611–624. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2020.20060864

- Martens, A., Goldenberg, J. L., & Greenberg, J. (2005). A terror management perspective on ageism. Journal of Social Issues, 61(2), 223–239. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.2005.00403.x

- McConatha, J. T., Schnell, F., Volkwein, K., Riley, L., & Leach, E. (2003). Attitudes toward aging: A comparative analysis of young adults from the United States and Germany. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 57(3), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.2190/K8Q8-5549-0Y4K-UGG0

- Menninger, W. W. (1991). Patient suicide and its impact on the psychotherapist. Bulletin of the Menninger Clinic, 55(2), 216–227.

- Neimeyer, R. A., Fortner, B., & Melby, D. (2001). Personal and professional factors and suicide intervention skills. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 31(1), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.31.1.71.21307

- Nemiroff, L. (2022). We can do better: Addressing ageism against older adults in healthcare. Healthcare Management Forum, 35(2), 118–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/08404704221080882

- Norheim, A. B., Grimholt, T. K., & Ekeberg, Ø. (2013). Attitudes towards suicidal behaviour in outpatient clinics among mental health professionals in Oslo. BMC Psychiatry, 13(1), 90. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-13-90

- Obuobi-Donkor, G., Nkire, N., & Agyapong, V. I. (2021). Prevalence of major depressive disorder and correlates of thoughts of death, suicidal behaviour, and death by suicide in the geriatric population—A general review of literature. Behavioral Sciences, 11(11), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11110142

- Pope, K. S., & Tabachnick, B. G. (1993). Therapists’ anger, hate, fear, and sexual feelings: National survey of therapist responses, client characteristics, critical events, formal complaints, and training. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 24(2), 142–152. https://doi.org/10.1037/0735-7028.24.2.142

- Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, D. A., Yershova, K. V., Oquendo, M. A., Currier, G. W., Melvin, G. A., Greenhill, L., Shen, S., & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial validity and internal consistency findings from three multisite studies with adolescents and adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704

- Punchik, B., Tkacheva, O., Runikhina, N., Sharashkina, N., Ostapenko, V., Samson, T., Freud, T., & Press, Y. (2021). Ageism among physicians and nurses in Russia. Rejuvenation Research, 24(4), 297–301. https://doi.org/10.1089/rej.2020.2376

- Pyne, K. (2020). Age bias in clinical judgment: Moderating effects of ageism and multiculturalism [Doctoral thesis, University of Denver]. Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 1834. https://digitalcommons.du.edu/etd/1834

- Reeves, A., & Mintz, R. (2001). Counsellors’ experiences of working with suicidal clients: An exploratory study. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 1(3), 172–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733140112331385030

- Samuelsson, M., & Åsberg, M. (2002). Training program in suicide prevention for psychiatric nursing personnel enhance attitudes to attempted suicide patients. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 39(1), 115–121. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0020-7489(00)00110-3

- Shiles, M. (2009). Discriminatory referrals: Uncovering a potential ethical dilemma facing practitioners. Ethics & Behavior, 19(2), 142–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420902772777

- Stavrevska, E. B., & Smith, S. (2020). Intersectionality and peace. In The Palgrave encyclopedia of peace and conflict studies (pp. 1–8). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-11795-5_120-1

- Uncapher, H., & Areán, P. A. (2000). Physicians are less willing to treat suicidal ideation in older patients. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 48(2), 188–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03910.x

- Warner, D. F., & Brown, T. H. (2011). Understanding how race/ethnicity and gender define age-trajectories of disability: An intersectionality approach. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 72(8), 1236–1248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.02.034

- World Health Organization. (2019). Suicide: One person dies every 40 seconds. www.who.int/news/item/09-09-2019-suicide-one-person-dies-every-40-seconds

- Zalsman, G., Hawton, K., Wasserman, D., van Heeringen, K., Arensman, E., Sarchiapone, M., Carli, V., Höschl, C., Barzilay, R., Balazs, J., Purebl, G., Kahn, J. P., Sáiz, P. A., Lipsicas, C. B., Bobes, J., Cozman, D., Hegerl, U., & Zohar, J. (2016). Suicide prevention strategies revisited: 10-year systematic review. The Lancet. Psychiatry, 3(7), 646–659. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30030-X

- Zeppegno, P., Gattoni, E., Mastrangelo, M., Gramaglia, C., & Sarchiapone, M. (2018). Psychosocial suicide prevention interventions in the elderly: A mini-review of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2713. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02713