Abstract

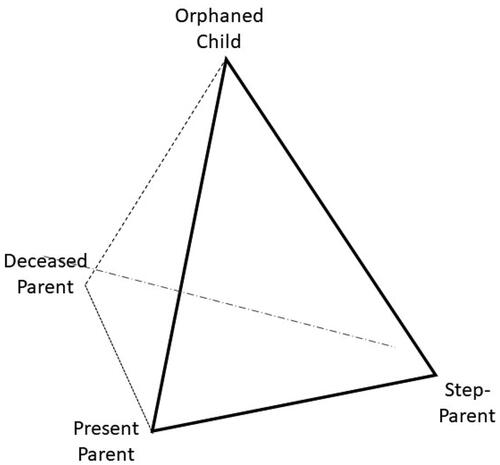

The current qualitative interpretative phenomenological study explored the intricate experiences of Israeli adults who lost a parent during childhood and subsequently navigated the challenges of adapting to a stepfamily dynamic. Through semistructured interviews, nine participants revealed three key themes: “Unbreakable Bonds: Loyalty to the Deceased Parent,” illustrating efforts to preserve the original family structure amid changes; “Replacement Bonds: Loyalty to the New Parent,” depicting the loyalty conflicts arising when connecting with a stepparent; and “Harmonic Bonds: Loyalties to All Three Parents,” showcasing instances in which bereaved children successfully maintained connections with their deceased parent while forming meaningful relationships with their stepparent and living biological parent. The study findings informed a model elucidating the dialectical stance family members may adopt in response to such complexities. The model emphasizes the prioritization of orphaned children’s emotional needs in a pyramid-shaped family structure, in which the psychological presence of the deceased parent remains integral.

Introduction

For young children, the death of a parent is an extreme and potentially traumatic event that inevitably involves the collapse of the familiar family structure (Biank & Werner-Lin, Citation2011; Feigelman et al., Citation2017). Children whose remaining parent remarries face additional emotional challenges related to adjusting to a new family and maintaining relations with living and deceased parental figures (Papernow, Citation2018). Forming triangular family relationships, such as parent–child triads (Minuchin, Citation1985), is one way of coping with such family structures.

When facing varied forms of stress in interpersonal relationships, family members often create “family triangles” consisting of three people who respond to that stress (Kerr & Bowen, Citation1988). According to this approach, two individuals pull in the third to relieve the tension among them and stabilize their relationship. Chronic triangulation is common, usually between two caregivers and a child, in families facing stressful, anxiety-provoking conditions (Ross et al., Citation2016). The current study examined a unique condition in which the child initiates a family triangle in response to stress following the loss of a parent.

From the child’s point of view, the deceased parent, who formed one edge of the family triangle, is no longer present. Additionally, the ability of the living parent to maintain the family structure is damaged due to personal loss and grief. The child has to deal with even more changes imposed on their life when the living parent remarries. When the living caregivers maintain an appropriate caregiver relationship with the child, the triangle is said to be balanced and thus, helpful to the functioning of the family (Ross et al., Citation2016). However, a child triangulated into parental or familial conflict may serve as a scapegoat, mediator, or member of a cross-generational coalition with a caregiver. This triangulation can harm the child’s development and the family structure (Colapinto, Citation2019).

Coalitions and triads in bereaved families

The family triad is a basic construct presented by family system frameworks and generally defined as the involvement of a third person in the relationship of two other people (Minuchin, Citation1985). They are naturally formed when significant emotional relationships occur between a couple or dyad and a third person, such as the relations between two parents and their child. This structure has been categorized in four major groups, according to the nature of the relations between partners (Bell et al., Citation2001): (a) balanced, in which all members are welcome and take part as accepted partners; (b) pushed out or scapegoat, in which one member is viewed as a disturbance to the peaceful existence of the family structure; (c) pulled in (cross-generational coalition), in which a child is invited, intentionally or subconsciously, to play a role in the parental relationship; and (d) mediator, in which the child bridges and connects the parents. Consequently, family triangles can be both helpful and detrimental to emotional equilibrium.

Family triangles are a well-established coping mechanism in times of stress (Kerr & Bowen, Citation1988). Whenever more than three people are involved in stress management, their coping is conceptualized as triangles that function in parallel. The same family members sometimes play a role in more than one triangle. For example, a divorced parent can be involved in two triangles: one with his child and current wife, and the other with his current wife and her daughter from an earlier marriage. When the family structure changes dramatically, like in the case of the loss of a parent, the remaining family members face uncertainty regarding their role in the newly formed family structure. This uncertainty might manifest in worries regarding who are the family members and what are the new family boundaries (Boss, Citation2016; Suanet et al., Citation2013).

Keeping a continuous bond with the deceased parent is common in such cases and essential for the development of the grieving process (Normand et al., Citation1996). However, in some cases, bonds with parents—either living or deceased—can be unbalanced and include boundary ambiguity and crossings. Such cases can be defined as cross-generational coalitions (Colapinto, Citation2019; Kerig & Swanson, Citation2010). These triangles are often a solution for a stressogenic situation, which can be permanent or temporary (Kerr & Bowen, Citation1988). If the living parent remarries, the bereaved child and two living parents have to decide whether to stick to the old familiar triangle structure of a child and two parents and moreover, what kind of relations the family will keep with the deceased parent (Normand et al., Citation1996).

Dealing with conflictual loyalties according to Boszormenyi-Nagy’s contextual theory

Contextual family theory posits that people are born into a complex and unique web of relationships featuring a matrix of motives, entitlements, and choices (i.e. context). The impact of preceding generations endures in the present milieu and stretches into future generations. Shared roots, heritage, and ethnicity form each person’s distinctiveness, with exclusive ties to others (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, Citation1973). At the heart of these connections lies a need for reciprocity and trustworthiness derived from mutuality, with regard for others being integral to maintaining this equilibrium. This contextual theory posits relational ethics as one primary constituent (Le Goff, Citation2001).

The concept of loyalty holds significant importance in this context and is understood as an existential and intergenerational bond rather than a mere feeling of loyalty or disloyalty toward another. Scholars have regarded loyalty as a crucial component of relational ethics, encompassing fairness, reliability, engagement in relationships, solidarity, and reciprocity (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, Citation1973). According to this formulation, a child who receives existence, care, skills, and knowledge from their parents and previous generations is bound to their family by an indestructible tie of debt, even in the face of death, abandonment, separation, or estrangement.

Loyalty inevitably involves choice. It is a process in which a child preferers one parent, so there is always a “chosen” parent and a “banished” parent (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, Citation1973). Thus, loyalty is a triadic, relational, and conflicted matter. Split loyalty, a situation in which “a child is forced to choose one parent’s love at the cost of seeming to betray the other parent” (Le Goff, Citation2001, p. 151), occurs in cases when the child is divided between their parents. In this situation, the child is deprived of the acknowledgment of one parent and their right to exchange with them. Acknowledging this aspect might explain the bereaved child’s mixed feelings when facing the need to adjust to a newly formed family once the living parent remarries (Papernow, Citation2018).

Cultural context of Judaism

Judaism provides a social, cultural, and spiritual framework to life, including specific support and guidance in times of loss (Rubin, Citation2015). Traditionally, upon loss, Jewish people are expected to focus solely on the loss in a period of sacred time called Aninut. After the burial, bereaved Jewish people are expected to withdraw into grief for 7 days (Shiva), then continue mourning along with the continuation of life following certain traditional ceremonies (Shloshim, Shana memorials, etc.). Jewish tradition emphasizes five encompassing elements that provide a holistic framework for bereaved people and their grief. These elements are aimed to help them come to terms and accept the reality of the loss and its implications; encourage a temporary moratorium, followed by gradual restoration of functioning; shape and support continuing bonds with the deceased person; enhance and mobilize social support; and help in the post-loss meaning-making process. This traditional framework is well-established and can offer a comfortable, familiar source of support. However, it might also represent social expectations and demands.

Present study

The relations between stepparents and stepchildren have been studied before, but mostly in families with divorced parents (Bray, Citation2019). Bereaved children’s experiences in newly formed families have been less investigated. Therefore, the present study examined the coping strategies children use to restore their sense of safety in the family structure while living with one parent who remarried after the death of their other parent. We examined intergenerational triangles and loyalties that emerge in this context, a unique case in which cross-generational coalitions and conflictual loyalties might involve both living and deceased family members. This perspective allows a broader understanding of children’s coping methods with parental grief. Considering this condition in its cultural context provides an opportunity to explore its unique nuances. To the best of our knowledge, this aspect of bereaved children’s ongoing relationships with their deceased and living parents has not been previously examined or described.

Method

The present study used interpretive phenomenological analysis (IPA), a qualitative approach most suited to revealing the perception and interpretation of participants’ emotional experiences (Smith & Osborn, Citation2015). This method is designed to enhance integrational notions stemming from various levels of data interpretation; therefore, it was suitable for this study (Clark et al., Citation2019), which aimed to gain a deep understanding of the complex interactions among family members and their perceptions of these interactions.

Participants

The study cohort’s size and demographic composition aligns with the theoretical dimensions of interpretive phenomenological analysis. The purposive selection of participants explicitly targeted individuals with pertinent experiences. Thus, we recruited participants in accordance with two inclusion criteria: (a) individuals who lost a parent at a young age and whose remaining parent remarried, and (b) participants aged 18 (official age of maturity in Israel) or older at the time of the interview. Furthermore, the sample’s modest size and homogeneity ensured prioritization of depth of insight over breadth of data collection (Wagstaff & Williams, Citation2014). Consequently, we used criteria sampling combined with comfort sampling (Patton, Citation2015) to recruit nine Israeli adults who lost their parent at an early age—seven women and two men. Participants’ mean age was 36.3 years (SD = 7.9) at the time of the study, and their mean age when they lost a parent was 10.6 years (SD = 3.8). Five participants had lost their father and four lost their mother due to various causes (illnesses, accidents, etc.). The average time before their living parent remarried was 3.4 years (SD = 2.5), and most participants were married with children at the time of the interview (one was single). All participants were either working or studying.

Procedure

Before beginning this research, we applied for and received approval from the institutional review board of the second author’s university (Approval No. AU-SOC-MMS-20211222). Ethical issues were addressed and discussed throughout the research process, starting from the research planning stage and continuing until publication. For example, we did not interview individuals shortly after their parental loss. Two conversations with each potential participant occurred a few days apart to ensure their voluntary willingness to participate in the research. During initial conversations with potential participants, they received information about the interviewers and researchers to make sure no personal acquaintance would affect the study and its data. Before the research interviews, we provided detailed information to all potential participants concerning the research process, interview setup, and how the narratives were likely to be used. We provided this information both orally and in written form. Careful attention was given to issues of confidentiality, and we assured the participants that their personal details would be changed during the interview transcription process, hence protecting their identity. To ensure participants’ privacy, once they confirmed their participation, no personal identity details were provided to other members of the research team. Interview content was only shared after participants’ names were changed. Pseudonyms are used in this article to ensure anonymity. Additional efforts were made to protect participants’ well-being, such as informing them of available psychological support should they feel emotional distress at any point during the research project; none of the participants used this service.

All potential participants were debriefed on the purpose and procedures of the study, and each participant who agreed to participate provided signed informed consent. They completed in-depth semistructured interviews lasting approximately 2 hours. Participants had the choice to decide where they wanted to meet for the interview. All interviews were held at participants’ home, per their choice. One of the best ways to gain an in-depth understanding of people’s perceptions of their lives and social worlds is through in-depth semistructured interviews (Hollway & Jefferson, Citation2016). This technique is especially appropriate for interpretive phenomenological analysis (Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2012) and when addressing sensitive topics such as loss (Mahat-Shamir et al., Citation2021). In-person, semistructured, one-on-one interviews have traditionally been the best source of rich, detailed information (Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2012). Thus, the interviews were conducted in a flexible manner, with question phrasing adjusted based on the flow of the interview and each participant’s answers. The questions were intended to be an invitation to share personal experiences and engage in thoughtful dialogue regarding the research questions.

The interview guide was based on Mahat-Shamir et al.’s (Citation2021) guidelines for revealing meaning construction in loss and included the following questions: What does losing a parent at a young age mean for you? How do you make sense of your loss? What do you think about yourself in relation to your parent’s death? What do you think about yourself in relation to your surviving parent’s remarriage? Are you still connected to your deceased parent over the passing of time? How? How have your feelings and reactions toward the loss changed over time and after the remarriage of your remaining parent? How did your close family and friends react to your parent’s death? How did your close family and friends react to your parent’s remarriage? In what ways were others involved in your grieving process?

Interviewers were two advanced social workers trained in qualitative interviewing by the second author. To obtain a reflective state, the interviewers received continuous guidance from the second author via weekly meetings throughout the data collection period.

The interviewers took opportunities to probe other interesting and important issues that arose if initiated by the participant rather than the interviewer (e.g. notions regarding grief or influences of the grief process on current spousal or parenting issues). The involvement of two interviewers allowed for a broader perspective on the experience being studied, because each interviewer’s approach was somewhat different. Nevertheless, their common professional background and involvement in the training process ensured the overall homogeneity of the data collection methodology. All interviews were conducted in Hebrew, recorded, and transcribed verbatim. Parts of the transcripts were translated for use in this article.

Data analysis

We analyzed the data according to IPA methods. In line with Smith et al. (Citation2022), we initially immersed ourselves in the text while attuning to the participant’s perspective. Subsequently, we engaged in further reading to delve deeper into the nuances, concurrently documenting personal reflections and underlying preconceptions that surface during the process. We interrogated our assumptions regarding the subject matter and continually reassessed our responses and choices, employing research journals for this purpose (Smith & Nizza, Citation2022). Second, we generated exploratory notes wherein we dissected the semantic and linguistic aspects of the transcript. This involved crafting comprehensive descriptions of the data by closely examining the keywords and expressions articulated by the participant. This phase also involved the use of ATLAS.ti. Third, we formulated experiential statements by transitioning from the original transcript to meticulously crafted descriptions, preserving intricacy while distilling core concepts.

Fourth, we embarked on identifying connections among these experiential statements, initiating the process of organizing, amalgamating, and reshaping themes in relation to one another. Fifth, we consolidated and structured experiential statements, assigning names to the Personal Experiential Themes (PETS) pertinent to the case, thereby accentuating its personalized attributes. Sixth, we progressed to the subsequent case, examining another transcript and endeavoring to analyze it autonomously from previous ones, following the same sequential steps. Seventh, we identified patterns across cases, comparing and contrasting Personal Experiential Themes (PETS) to derive interpretations of Group Experiential Themes (GETS).

Rigor

Several strategies were implemented to enhance the findings’ credibility and transferability (Faulkner & Atkinson, Citation2023). We used these strategies in keeping with interpretive phenomenological analysis methodology. First, the use of in-depth semistructured interviews enabled consistency checking and inconsistency clarification during the interviews (Pietkiewicz & Smith, Citation2012). Second, interviews were conducted to capture the realities and perspectives of participants as accurately as possible. Therefore, no attempts were made to push participants toward a certain way of thinking during interviews, and they had many opportunities to clarify their thoughts. Additionally, the authors kept a field journal, and discussions between the two authors were consistently used to identify their potential biases and preconceived assumptions. Third, credibility and transferability were enhanced by the analysis being conducted by two researchers of different academic backgrounds, life stages, and professional experience with bereaved individuals (none of the authors has personal experience with losing a parent at a young age). Despite these differences, no major disagreements regarding the researchers’ analyses occurred. Moreover, a group of colleagues examined their analysis to ensure adherence to the research process, along with participant reflection (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018), enhancing the accuracy and reasonableness of the interpretation of the data. Thus, the data and researcher interpretation were consistently judged from various perspectives at all stages of analysis (Faulkner & Atkinson, Citation2023). This way of working is in keeping with Benner et al. (Citation2009) assertion that using multiple readers to interpret text often leads to additive insights. Furthermore, the following detailed description of the analysis and participants’ exact quotes enable an assessment of the process through which the results were obtained and critical evaluation of the researchers’ interpretation of participants’ input.

Results

The findings present participants’ experiences of coping with parental loss. We begin this section by presenting participants’ descriptions of the multiple challenges they faced at these times, including the double loss of their parents and issues when the remaining parent remarried. Following this part, we present three main themes that emerged from analyzing participants’ data. These themes deal with participants’ attempts to maintain psychological equilibrium and well-being while facing hurdles as they adjusted in the newly formed family. The first theme, “Unbreakable Bonds: Loyalty to the Deceased Parent” captures participants’ anxiety as they realized their new condition as orphans and attempted to retain their known family structure. For some participants, these efforts manifested as keeping a continuous bond with and loyalty to the deceased parent, along with emotional distance from the new stepparent. The second theme, “Replacement Bonds: Loyalty to the New Parent,” features examples of bereaved children solving their loyalty conflict by connecting with their new stepparent. Finally, “Harmonic Bonds: Loyalty to All Three Parents” presents cases in which the bereaved children managed to keep their continuous bond with their deceased parent while establishing a new, meaningful relation with their stepparent and maintaining a meaningful connection with their living biological parent.

All participants described the loss of a parent as shattering a safeguarding psychological shield. Most of them described the chaos that accompanied the death of their parent and the changes it brought to their seemingly safe world. For example, Sarah, who lost her mother when she was 11 years old, described:

Upon my mother’s death, the house was very stressful. … There were many fighting and shouting matches between my father and my brother. … But I also had some good moments with her, when she talked to me … but in the final weeks, she was all medicated and painful, and I was very lonely.

My father turned off. He would sit for whole evenings and cry. And I was really afraid because he was so sad and withdrawn. Half of him was gone when she [her mother] died. … And I felt lonely and worried and had no one to turn to. No one was there for me. It was like losing both parents.

Theme 1: Unbreakable bonds: loyalty to the deceased parent

Participants described a threat of losing their remaining parent, which is natural after losing one parent, as an emotional response to the remaining parent’s new spousal relationship. Noga, who lost her father when she was 6, described:

When they told me they were getting married, I cried more than I did when I was told that my father died … as if crying about his loss, which didn’t happen back then, came out now. … I felt abandoned, as if [the new husband] took away the only thing I had, the only anchor left in my life. So, I would prefer if he wasn’t a part of my life.

Their resistance to the new spousal connection was an attempt to preserve security in the original family unit, or at least its remains. These bereaved children perceived the new spousal relationship as an additional form of abandonment on the part of their living parent, thus encouraging them to hold strongly to their bond with the deceased parent. Other participants described various forms of continuing the bond they had with their deceased parent throughout the years as a way of maintaining their original psychological family structure.

However, keeping these connections had consequences for their relations with their living parental figures. Ziva, who lost her mother when she was 12, explained how she understood the potential conflict of living with her father and his new spouse in a newly formed family while keeping a bond with her biological mother:

I was safeguarding my [late] mother’s existence. … For a long time, I used to smell her clothes, and even bought her kind of perfume to remember her odour. … When my dad got married, he stopped visiting her grave, and I couldn’t accept that. I had a really, really hard time with it. … I saw my parents as a solid unit, and suddenly it was different. I realized that he is actually a separate person who was married to my mother for a period of time, and now it was over. I couldn’t understand how it would be from now on.

A stepparent joining the family might also unintentionally cause pain because they symbolize the continued development of life and the fact that the deceased parent will no longer play an active part in the family. Omer, who lost her father when she was 15, said that after her mother remarried: “I had to fight for the continuation of my original nuclear family and for us staying together.” Thus, in light of the living parent’s commitment to a new marriage, some family members experience the pain associated with their loss once again and might fear abandoning their deceased parent’s memory. As the parental triangle collapses, orphaned children might look for ways to rehabilitate it or keep it safe.

Theme 2: Replacement bonds: loyalty to the new parent

Children naturally tend to keep their loyalty to both of their parents. Consequently, when one parent dies and the surviving parent remarries, their children encounter a challenge. In this new condition, they have to manage their loyalty to the deceased parent while also accepting a new parent, who represents the surviving parent’s decision to move forward with life. It is challenging for children to exhibit loyalty to one parent without experiencing disloyalty toward the other and they may encounter split loyalty (Le Goff, Citation2001).

Establishing a coalition with the new stepparent is one solution that four participants described in response to their loss-related distress. For example, Jane, who lost her mother when she was 9, described:

At first, I hated my father’s new wife. It felt this new marriage was a betrayal and lack of loyalty toward my mother. Marrying my father means taking my mother’s place, which means forgetting her even more. … But when I realized that I had no way to change it, I started to really need my stepmother. At some point, I even wanted to call her “mother.” It was a very deep need. … And she also made a huge effort so that we would build new and good relations within our home. But allowing me to call her “mother” was too difficult for her, too, so she told me, “Let’s settle for [her name].”

Omer, who lost her father when she was 15, described the emotional complexities involved with this experience:

At first, I called my mother’s new spouse “father,” and I agreed that he would hug me and was excited by it, because I had never received a paternal hug before and it really moved me. But after some time, I made clear that I would not treat him as a father, we would maintain distance and keep “touch” [an Orthodox Jewish tradition that prevents strangers, men and women, from touching each other, even in a platonic way]. Mom didn’t agree with me about it, so I made the decision myself … because he is not our father. I appreciate and am grateful for him very much, but there are things where only my mother is welcome.

Children who have experienced the loss of a parent and witnessed their surviving parent remarry often grapple with complex psychological needs. This need revolves around seeking a connection with the stepparent to maintain a sense of security in the new family dynamic. Simultaneously, they deeply cherish their bond with the deceased biological parent and find it too painful to let go of that connection. Consequently, these children often find it challenging to invest fully in a relationship with the stepparent as a direct replacement for the deceased parent. Instead, they navigate a delicate balance, choosing to remain loyal to all three individuals involved—both parents, living and deceased, and the new stepparent, as demonstrated in the following theme.

Theme 3: Harmonic bonds: loyalties to all three parents

Participants described different ways of solving their conflictual conditions, establishing good coalitions with their living parents, and protecting their bond with the deceased parent. Orit, who lost her mother when she was 8, described this unique facet of her coalition with her new parent:

My father was a terribly rigid person, and even as a child, I understood that a woman at home would make it easier for me to deal with him, so I received his new partner with open arms. … From the moment he introduced her to me, I was constantly making sure that she would stay with us. I would call to invite her, prepare everything for them, make sure she would come, that there would be a nice atmosphere. … But she wasn’t trying to fill my mom’s place, and I didn’t want her to fill her place either. I wasn’t ready to give up on my mother and lose her again. … And I think the relationship between me and my father has become better since [stepmother’s name] joined us.

I truly accepted [mother’s second husband] when I realized that he was my ally, not a rival or an enemy. I realized that he does not threaten my mother’s attention, but that he cares for her, and that this can be my way of helping her as well. I have come to terms with the fact that he is not going to be a replacement for my dad, and Mom also acknowledges that.

Discussion

The findings present participants’ endeavors to reconcile their split loyalties, which involved different combinations of maintaining allegiance to the deceased parent and repudiating or embracing the new parent and disowning the deceased one. Between these ends of the continuum, participants struggled to harmonize their loyalties to all three parents, living and deceased, biological and stepparent. Interpersonal coalitions are a natural response in times of stress (Colapinto, Citation2019), and the participants of the current study used them to cope with changes in their families.

Maintaining a continuous relationship with a deceased parent has unique meaning for bereaved children and often holds a special place in their heart that can last throughout life (Papernow, Citation2018). The findings of the current study are in line with this understanding, and our participants used several idiosyncratic metaphors to refer to their relationships with their parents, such as “anchor,” “solid unit” etc. Similarly, they emphasized that even though they accepted the relationship with their stepparent as part of their changing world, it would always exist alongside the continuing bond to their original parent. Thus, they expressed dual loyalty—a situation in which the child holds even and balanced relationships with all their parents—as a more balanced solution than split loyalty. Acceptance of this dual loyalty by the living parents might inspire trust and confidence in the bereaved child’s shattered world. Also, it can reassure the child that there is no intention to replace their deceased biological parent with the stepparent—a commonly perceived threat voiced by the current study’s participants.

Only by using such an approach can the newly formed family become whole, because it allows all living members to reshape their familial coalitions, including those with the stepparent and deceased parent, as legitimate partners in the stepfamily architecture (Papernow, Citation2018). As Papernow (Citation2018) put it, death ends life, not the relationship, and “becoming a stepfamily is a process, not an event” (p. 46).

However, this process can be tough because it contains built-in loyalty and bonds. Bereaved children might feel like they are betraying the deceased parent by forming triangles and coalitions with new family members, especially the new stepparent. Putting pressure on children to accept the stepparent like a biological parent can leave them feeling alone with their loss, fearful of losing their living parent to a new spouse, and guilty about not fulfilling their living parent’s expectations (Blank & Werner-Lin, Citation2011). When coping with this complicated challenge is involved with developmental characteristics, such as a child’s less advanced cognitive state or an adolescent’s rigidness or rebelliousness, it can be doubly hard for the child and parents. Because the parents inevitably play a crucial role in the bereaved child’s development, they both affect that development and are affected by the child’s reactions. Hence, this situation holds the risk of developing into a vicious cycle.

For example, guilt-laden magical thinking, fantasies of reunion, and continuous devastation and regret about the life that could have been had their parent lived might bother the bereaved child for years after the loss (Blank & Werner-Lin, Citation2011). Once the living parent remarries, these fantasies might affect the new family. The participants of the current study described experiencing this scenario. According to contextual family theory, since birth, children engage in mutual, active giving toward their parents, and parents attain self-validation by fulfilling their parental duties through relationships with their children. This act of giving to parents is valuable for children because it prepares them to receive in the future, thus creating a reciprocal cycle of mutual self-validation (Le Goff, Citation2001). Although the child–parent relationship is characterized by asymmetry, acknowledgment from parents is integral to the child’s self-validation and continuity of existence. Any refusal of the child’s contributions by parents can lead to unjust treatment and development of a harmful sense of entitlement (Boszormenyi-Nagy & Spark, Citation1973). The current study’s participants described such efforts to arrange their world after the loss, including struggles to create stable, safe relations with the adults on whom they depended.

In the case of parental loss, the deceased parent’s absence inevitably damages the fulfillment of the child’s developmental needs. Moreover, it affects their coping sources, because they lack familiar support to accomplish normative or grief-related developmental tasks. If the surviving parent is too occupied with their own grief, the child might feel even more stressed and anxious, having seemingly lost both parents. Participants in the current study described such conditions and suggested that accepting their stepparent was one way to support their living parent’s rehabilitation or regain an active, living parent. Because children’s grief never fully resolves (Blank & Werner-Lin, Citation2011), they have to face related challenges throughout their lives, often at different life transitions, which offers opportunities to resolve these issues again and in different ways during their maturation process. Children who face traumatic loss at a relatively young age tend to cope with the trauma through behavioral solutions, because life summons them forward with new challenges that demand their adaptation. Specifically, Jewish tradition encourages keeping continuous bonds with deceased people (Rubin, Citation2015). Hence, participants in the current study dealt with the complex task of moving forward with their life while maintaining a connection to their painful past. The current study shed light on this sensitive topic, which is often overlooked, and highlighted the nondichotomous nature of these children’s coping methods.

Clinical implementations

Because the relationship with the deceased parent is an influential factor in a newly formed family (Normand et al., Citation1996), bereaved family members, professional clinicians, and others who treat children in such states would benefit from acknowledging the complicated emotional powers they face as they are emotionally tossed among edges of familial triangles. This condition is illustrated in . According to this understanding, the relationship with the deceased parent persists in the background of the new family’s life. One task for psychotherapists when supporting children and families coping with such a condition is to help the whole family system regain its emotional equilibrium through balancing the different familial relationships. Gaining this balance can enhance the family’s harmony and peace of mind.

Study limitations

This study relied on a specific, relatively small cohort of Jewish Israeli citizens. Although Israeli culture is very diverse and the participants had various levels of religious orthodoxy, their cultural norms and values may have influenced how they perceived and expressed their experiences. Orphans who belong to different cultures and societies where other cultural codes are observed might cope with this type of loss differently. For example, it is possible that people of traditional and collectivist cultures, where remarriage after loss is perceived in a more dichotomous way—encouraged or criticized—might face different powers that shape their coping. Moreover, because the participants were recalling events from their childhood, which occurred decades ago, the data they provided were based on their memory and could be incorrect. However, participants’ experiences and knowledge are a well-established source of data to study the human experience and have been the basic feature of the validated qualitative field of research for many decades. Further research is recommended to better understand the broader aspects and various nuances of children’s longitudinal coping with parental loss. Long-term research that follows a larger and more heterogenous population might serve this purpose.

Conclusion

When children face the traumatic loss of a parent followed by the remarriage of their remaining parent, they tend to develop various coping mechanisms. Establishing a parental triangle is a common phenomenon in such cases. Different emotional powers are involved in this process, influencing the child’s continuous coping with their loss. Acknowledging the complex nature of this process is crucial to support orphaned children and their family members in dealing with this challenging grief-related task.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Bell, L. G., Bell, D. C., & Nakata, Y. (2001). Triangulation and adolescent development in the U.S. and Japan. Family Process, 40(2), 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1545-5300.2001.4020100173.x

- Benner, P. E., Tanner, C. A., & Chesla, C. A. (2009). Expertise in nursing practice: Caring, clinical judgment and ethics. Springer.

- Biank, N. M., & Werner-Lin, A. (2011). Growing up with grief: Revisiting the death of a parent over the life course. Omega, 63(3), 271–290. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.63.3.e

- Boss, P. (2016). The context and process of theory development: The story of ambiguous loss. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 8(3), 269–286. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12152

- Boszormenyi-Nagy, I., & Spark, G. (1973). Invisible loyalties: Reciprocity in intergenerational family therapy. Brunner/Mazel.

- Bray, J. H. (2019). Remarriage and stepfamilies. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (pp. 707–724). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000099-039

- Clark, V. L. P., Wang, S. C., & Toraman, S. (2019). Applying qualitative and mixed methods research in family psychology. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Foundations, methods, and contemporary issues across the lifespan (pp. 317–333). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000099-018

- Colapinto, J. (2019). Structural family therapy. In B. H. Fiese, M. Celano, K. Deater-Deckard, E. N. Jouriles, & M. A. Whisman (Eds.), APA handbook of contemporary family psychology: Family therapy and training (pp. 107–121). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000101-007

- Faulkner, S. L., & Atkinson, J. D. (2023). Evaluating qualitative research. In: S. L. Faulkner & J. D. Atkinson (Eds.), Qualitative methods in communication and media. Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780190944056.003.0007

- Feigelman, W., Rosen, Z., Joiner, T., Silva, C., & Mueller, A. S. (2017). Examining longer-term effects of parental death in adolescents and young adults: Evidence from the national longitudinal survey of adolescent to adult health. Death Studies, 41(3), 133–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2016.1226990

- Hollway, W., & Jefferson, T. (2016). Eliciting narrative through the in-depth interview. Qualitative Inquiry, 3(1), 53–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049700300103

- Kerig, P. K., & Swanson, J. A. (2010). Ties that bind: Triangulation, boundary dissolution, and the effects of interparental conflict on child development. In M. S. Schulz, M. Kline Pruett, P. K. Kerig, & R. D. Parke (Eds.), Strengthening couple relationships for optimal child development: Lessons from research and intervention (pp. 59–76). American Psychological Association.

- Kerr, M. E., & Bowen, M. (1988). Family evaluation: An approach based on Bowen theory. W. W. Norton & Co.

- Le Goff, J. F. (2001). Boszormenyi-Nagy and contextual therapy: An overview. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 22(3), 147–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1467-8438.2001.tb00469.x

- Mahat-Shamir, M., Neimeyer, R. A., & Pitcho-Prelorentzos, S. (2021). Designing in-depth semi-structured interviews for revealing meaning reconstruction after loss. Death Studies, 45(2), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2019.1617388

- Minuchin, P. (1985). Families and individual development: Provocations from the field of family therapy. Child Development, 56(2), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129720

- Normand, C. L., Silverman, P. R., & Nickman, S. L. (1996). Bereaved children’s changing relationships with the deceased. In D. Klass, P. R. Silverman, & S. L. Nickman (Eds.), Continuing bonds (pp. 87–111). Taylor & Francis.

- Papernow, P. L. (2018). Clinical guidelines for working with stepfamilies: What family, couple, individual, and child therapists need to know. Family Process, 57(1), 25–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12321

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods: Integrating theory and practice. (4th ed.). Sage.

- Pietkiewicz, I., & Smith, J. A. (2012). A practical guide to using interpretative phenomenological analysis in qualitative research psychology. Psychological Journal, 18(2), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.14691/cppj.20.1.7

- Ross, A. S., Hinshaw, A. B., & Murdock, N. L. (2016). Integrating the relational matrix: Attachment style, differentiation of self, triangulation, and experiential avoidance. Contemporary Family Therapy, 38(4), 400–411. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-016-9395-5

- Rubin, S. S. (2015). Loss and mourning in the Jewish tradition. Omega, 70(1), 79–98. https://doi.org/10.2190/OM.70.1.h

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2022). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. SAGE.

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Smith, J. A., & Nizza, I. E. (2022). Essentials of interpretative phenomenological analysis. American Psychological Association.

- Smith, J. A., & Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis. In J. A. Smith (Ed.), Qualitative psychology: A practical guide to research methods (3rd ed., pp. 25–52). Sage.

- Suanet, B., van der Pas, S., & van Tilburg, T. G. (2013). Who is in the stepfamily? Change in stepparents’ family boundaries between 1992 and 2009. Journal of Marriage and Family, 75(5), 1070–1083. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12053

- Wagstaff, C., & Williams, B. (2014). Specific design features of an interpretative phenomenological analysis study. Nurse Researcher, 21(3), 8–12. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2014.01.21.3.8.e1226