Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic changed the way people lived, but also the way they died. It accentuated the physical, psychological, social, and spiritual vulnerabilities of patients approaching death. This study explored the lived experience of palliative inpatients during the pandemic. We conducted interviews with 22 palliative inpatients registered in a Canadian urban palliative care program, aimed to uncover how the pandemic impacted participants’ experiences of approaching end-of-life. The reflexive thematic analysis revealed 6 themes: putting off going into hospital, the influence of the pandemic on hospital experience, maintaining dignity in care, emotional impact of nearing death, making sense of end-of-life circumstances and coping with end-of-life. Findings highlight the vulnerability of patients approaching death, and how that was accentuated during the pandemic. Findings reveal how the pandemic strained, threatened, and undermined human connectedness. These lived experiences of palliative inpatients offer guidance for future pandemic planning and strategies for providing optimal palliative care.

The experience of approaching death is fraught with physical, psychological, social, and spiritual challenges (Ciemins et al., Citation2015; Donnelly et al., Citation2018; Yang et al., Citation2012). Toward the end of life, patients often find themselves navigating various issues touching on personal autonomy, control over the dying process, responsive care, psychosocial supports, and optimal communication (Black et al., Citation2018; Donnelly et al., Citation2018; Hansen et al., Citation2022; Rodríguez-Prat et al., Citation2016). Little is known, however, about how these were modified or shaped in the context of the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic.

After the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus outbreak a global pandemic in March of 2020 (Mahase, Citation2020), the end-of-life experience for many patients became distorted in previously unimaginable ways. The pandemic, for instance, saw public health measures imposed, which included visitor restrictions, the widespread use of personal protective equipment (PPE) (Gergerich et al., Citation2021; Harden et al., Citation2020; Muehlhausen et al., Citation2022; Schallenburger et al., Citation2022), and policies designed to maintain social distancing. This resulted in various challenges for patients including isolation and loneliness, a lack of family support, communication struggles with staff, and unmet functional needs based on healthcare providers having less time to attend to their patients’ personal care (Gergerich et al., Citation2021; Harden et al., Citation2020; Muehlhausen et al., Citation2022; Schallenburger et al., Citation2022).

When the study began, there was a significant reduction in the number of hospital admissions to palliative care, likely due to many of the aforementioned challenges, as well as fear of becoming infected with COVID-19. This fear likely reflected how little was known at that time regarding the clinical manifestations of the virus, which spanned from a common cold, to more severe conditions such as respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, multi-organ failure and even death (Guan et al., Citation2020). For many older adults on palliative care wards within hospitals reporting several outbreaks, as well as those at-home in need of palliative care, this was a grave concern and possible deterrent, given that several reports indicated that older adults who had underlying medical conditions were at a higher risk for severe illness from COVID-19 (Xu et al., Citation2020).

The pandemic also saw healthcare providers forced to weigh their obligations toward patient care against obligations for self-protection, while also enforcing strict public health measures (Pankratz et al., Citation2023). This threatened patients’ sense of dignity, given the absence of family and being responded to as a possible source of contagion undermined their sense of being supported, valued, and appreciated as whole persons (Chochinov et al., Citation2020). The absence of family often meant patient isolation, with overburdened healthcare providers struggling to respond to patients’ psychosocial and spiritual needs (Galchutt, Citation2022; Gergerich et al., Citation2021; Schallenburger et al., Citation2022). Public health restrictions left many patients dying alone, prompting the need to examine how notions of dignity and the experience of approaching death were being shaped in the midst of the global pandemic.

The aim of this study was to explore the lived experience of inpatients registered in a Canadian urban palliative care program dying of any cause during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, we set out to answer the question, how did the pandemic influence how these patients approached death in the midst of this global crisis? While there have been a few retrospective studies on the impact of the pandemic on palliative care services (Ersek et al., Citation2021; Lopez et al., Citation2021; Moriyama et al., Citation2021), on understanding the complexities of palliative care provider grief (Kates et al., Citation2021; Rowe et al., Citation2021; Wallace et al., Citation2020; Bradshaw et al., Citation2022;), in-patient palliative care profiles (Hetherington et al., Citation2020), and reports on family perspectives (Dennis et al., Citation2022; Hanna et al., Citation2021; Pauli et al., Citation2022), there has not been a prospective study focused on the lived experience of palliative inpatients during the pandemic, and no data examining how these experiences impinged on dignity from patients’ perspectives.

By examing the experiences of patients dying during the COVID-19 pandemic, we aimed to provide data driven insights that might inform strategies to support patients nearing death, should the world face future equivolent healthcare crises.

Methods and materials

Study settings

This study took place while Manitoba was experiencing the second wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. There was still much uncertainty regarding virus transmissibility, causing the provincial government to focus on urging Manitobans to get vaccinated. Continued surges in COVID-19 cases fueled by more transmissible mutated coronavirus variants led to the imposing of tighter restrictions. At this time, there were 600 outbreaks, 343 within long-term care facilities. Manitobans were told to remain at home except for essential purposes and school closures continued. Mask mandates, testing and contract tracing became more routine, while bed shortages in Intensitve Care Units continued (Barrett et al., Citation2020; Manitoba, Citation2022).

Study design

We used a qualitative study design rooted in reflexive thematic analysis. This approach created the opportunity to analyze the patterns and themes within the dataset to identify the underlying meaning. Thematic analysis is useful when looking for subjective information such as a participant’s experiences, views and opinions. For this reason thematic analysis is often applied to interview data, such as in this study. This allowed for a very detailed exploration of individuals’ experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Van Orden et al., Citation2010).

Participants

Between April 2021 and December 2021, we recruited 22 palliative care inpatients from two care facilities affiliated with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority in Manitoba, Canada. Both these facilities offer specialized palliative care services. Eligiblity criteria included: (a) being 18 years of age or older, (b), having a life expectancy of 6 months or less, (c) the ability to read and speak English (d) being registered within the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority Palliative Care Program and (e) having a Palliative Performance Scale (PPS) score of 40% or higher. The latter threshold identifies patients who are unable to do most activites independently, require assistance with self care, but are competent, able to to provide informed consent and complete the protocol as described (Ho et al., Citation2008).

Procedures

Recruitment took place through referrals made by healthcare providers, who identified patients meeting study eligibility criteria. Eligible patients were asked permission by their healthcare provider to release their name as a potential study participant to a member of our research team, who then informed them about the study in more detail, and answered their questions. Patients were informed that participation was voluntary and refusal would not affect their access to quality, competent care. After written informed consent was obtained, participants provided demographic information and completed an interview.

Data collection

We developed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended interview questions specific to how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted the experience of those receiving inpatient palliative care toward the end-of-life. Interview questions were open-ended in nature, to facilitate a deep exploration of the topic and to receive a rich description of each participant’s experiences.

The protocol was flexible to accommodate and respect individual patients’ needs and capacity for engagement, consistent with qualitative interview guidelines (the interview framework can be found in Appendix A). Interviews took place in patients’ rooms located on palliative care units affiliated with the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority. Interviews were conducted by a research team member trained in qualitative research (SP). Interviews ranged from 40-70 minutes in length, depending on the patient’s willingness and interest responding to our questions, and illness related limitations. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim, de-identified, reviewed for accuracy, and uploaded into NVivo for thematic analysis.

We also explored considerations of dignity embedded within the model of dignity in the terminally ill. The model details various domains that can uphold or impinge on patient dignity. These include illness related factors (things that are mediated or emerge directly from the illness itself), the dignity conserving repertoire (subsumes existential and spiritual dimensions of personhood, and what imbues life with meaning), and the social dignity inventory (includes external factors that can influence whether patients feel their dignity is under assualt or being undermined) (Chochinov et al., Citation2002). We used this model to dicern if the pandemic challenged healthcare providers’ ability to offer dignity conserving care, and how this impacted inpatients’ sense of dignity.

Questionnaires

Demographic questionnaire

After providing consent to a member of the research team, participants completed a demographic self-report questionnaire. This included information on age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, occupational status, annual income, religion, living arrangement, ethnic origin, diagnosis and care setting. Their palliative performance score was calculated by the referring healthcare provider and included in their demographic information.

Study data was collected and managed using REDCap electronic data capture tools hosted at the University of Manitoba. Analysis was undertaken using SPSS software (IBM SPSS Statistics for Macintosh, Version 28.0). Descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation [SD], range, and percentages) were calculated for demographic data and patient outcomes.

Data analysis

Qualitative Data Analysis: When data collection was completed, qualitative analysis began. We engaged in the six-phase approach of reflexive Thematic Analysis to ensure trustworthiness of qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). QSR NVivo 12 qualitative research software (QSR, 2018) was used to assist with data organization.

Researchers began their analysis of the interviews by familiarizing themselves with the data through repeated readings and note taking. The initial coding was led by two members of the research team, who coded for as many themes as possible and extracted codes of data inclusively, as per Braun & Clarke (Citation2006). The purpose of initial coding is to complete line-by-line coding and stay very close to the data. The next phase, focused coding, involves making decisions about the initial codes to categorize the data, without sacrificing the details of the initial codes. Theoretical coding then allows for the creation of connections between the themes and sub-themes. During the next phase, researchers refined themes to create a “thematic map” based on consensus with the full research team (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). This led to some themes being discarded while others collapsed into each other, creating one broader theme. Others required breaking down into still smaller, separate themes, sub-themes and sub-subthemes. Once a satisfactory thematic map was created, we further defined and refined themes to be incorporated into the final analysis.

Reflexivity and rigor

To ensure rigor and trustworthiness of research, several procedures were followed in keeping with those outlined by Braun et al. (Citation2019) Braun & Clarke (Citation2019), and Tracy (Citation2010). Our team represented a broad range of professional experiences in end-of-life care research. Recognizing the possible impact of these differing lenses on the analysis meant researchers had to engage in an open and collaborative exchange of ideas (Braun et al., Citation2019). All team members engaged reflexively in their analyses, recognizing how their own experiences might shape their interpretation of the data (Tracy, Citation2010). In keeping with Braun & Clarke (Citation2019) reflexive thematic analysis procedures, the research team endeavored to recognize “researcher subjectivity, organic and recursive coding processes, and the importance of deep reflection on, and engagement with data” (Braun et al., Citation2019, p. 593). Researchers then coded independently and then came together to discuss their findings and revise the thematic framework accordingly.

The collaborative nature of the research methods applied throughout analysis also served to increase study rigor and credibility (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2003). As new themes emerged, and as codes expanded and collapsed, researchers continued to revisit the coding framework. Further, in keeping with Tracy’s (Citation2010) recommendations for ensuring study rigor, a coding journal was kept as an audit trail for all coding decisions.

Results

Participants were, on average, 83 years old and diagnosed most often with terminal cancer (n = 14; 63.6%). Participants primarily identified as female (n = 14; 63.6%), white (100%), and Christian (n = 17; 77.3%). The majority of participants were married (n-13; 59.1%), retired (n = 19; 86.4%), living alone (n-11; 50%), and had a high school education (n = 16; 72.7%). The average Palliative Performance Score was 49.8% (see )(See Supplementary Material).

Table 1. Characteristics of research participants (n = 22).

Thematic analysis

It is important to preface our findings by stating most participants expressed not having any reference point against which to compare their experience. One participant stated, “I’m getting excellent care here and I don’t really have anything to compare it with” (#09, 63-year-old female). Another stated, “I started with my illness after the virus. OK, so it’s sort of you know, you can’t really compare” (#03, 79-year-old female). Nonetheles, this study aimed to understand how end-of-life experience was shaped by the pandemic.

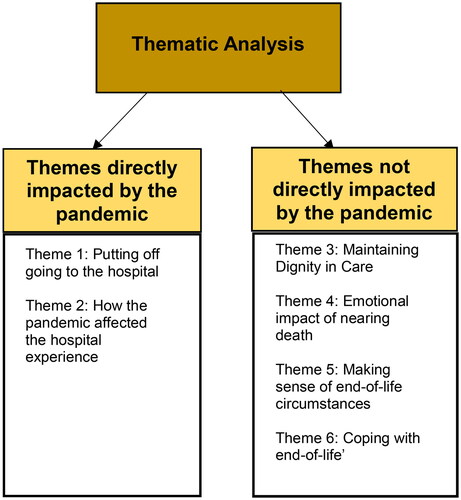

Data analysis revealed 6 main themes describing the overall end-of-life experience during the COVID-19 pandemic, revolving around the initial need for institutional care, the experience in the hospital, and finally, approaching end-of-life. Collectively, this framework contains a detailed and nuanced description of end-of-life experience for palliative inpatients during the pandemic, and how they adapted within the context of this global healthcare crisis. These themes included: 1. putting off going to the hospital; 2. the influence of the pandemic on hospital experience; 3. maintaining dignity in care; 4. emotional impact of nearing death; 5. making sense of end-of-life circumstances; and 6. coping with the imminence of death. Each theme was comprised of one or more subthemes and sub-subthemes.

Theme 1: Putting off going to the hospital

This theme describes patients delaying going to the hospital due to visitation restrictions, fear of separation from family and friends, feeling like a burden on the seemingly already overburdened healthcare system, and possible risk of infection. Avoiding hospitalization found patients having to tolerate pain or discomfort at home, relying increasingly on loved ones and risking feeling a burden to their family. Some participants indicated they eventually sought care in hospital, despite previous hesitations. At the time of this study, it appeared these aforementioned hesitations around going into hospital were influenced in some ways by the COVID-19 pandemic.

She [wife] was the same type as me. We’d sit out there and watch all the people, then I had to come here [hospital], and I thought it’s not for me. I don’t want to come here. I want to be with my kids. #12 (87-year-old, male).

Tolerating pain and discomfort at home

For some participants, avoiding the hospital meant having to endure pain and discomfort at home.

It’s like having a real sick stomach. You can’t get sick and get rid of it. You’ve got it continuously and it got to a point, I cried. It just feels bad, so that’s more or less why I ended up here, because the boys said they can’t give me the help that I would get here. So, I finally give in and said I would come. #12 (87-year-old, male).

Dependency on family and feeling like a burden

With participants remaining at home, families had to take on greater responsibility for delivery of care. Many participants experienced a decline in their personal health as a result, creating more challenges for their loved ones, causing participants to feel like an even greater burden as the pandemic went on.

Well they took me from Health Sciences Centre and the cancer treatment was radiation and didn’t work, and my wife was too old to take care of me at home. I don’t want to be a burden. #15 (63-year-old, male).

Coming into hospital late

With worsening symptoms and families becoming overwhelmed, participants described deciding to seek hospital care and services. This was often precipitated by mounting symptom severity and the need for emergency attention.

… it was the middle of December, I don’t know the date, I think somebody said 17th or 18th that I went to the hospital. I don’t even know the date, but I was like a goner. #18 (92-year-old, female).

Theme 2: How the pandemic affected the hospital experience

This second theme details the extent to which hospital experiences were impacted by the pandemic. For example, upon admission, participants described the challenges associated with navigating ongoing changes in pandemic policies, with specific concerns centered around mask wearing and policies that prohibited in-person contact, which meant a loss of support from loved ones.

So, nobody came to visit me other than my one son and my daughter. They kept it down to two. And, you know, he used to go grocery shopping for me, you know, that sort of stuff whereas now I don’t get that personal touch anymore … I think there’s no getting personal attention anymore. #3 (79-year-old, female).

Problems with having to wear a mask

To help mitigate virus transmission, participants described their experience of being required to wear a mask within the hospital, with many reporting difficulties breathing through their masks. Other challenges included altered visual perception that affected their certainty with ambulation, and experiencing physical pain behind the ears.

If they had any idea how difficult it is to breathe with your nose things. and I wear glasses, and then the mask. It’s not that it’s inconvenient, or uncomfortable so much as I feel like all I’m concentrating on is this slope in front of me. #9 (63-year-old, female).

Problems related to staff wearing masks

Participants expressed several challenges related not only to themselves wearing masks, but also in their interactions with the attending staff, who were also compelled to adhere to mask wearing policies. Participants expressed various challenges related to interpersonal communication with staff due to mask wearing. Of note, challenges related to facial recognition made it hard for patients to identify their healthcare providers. Participants also reported challenges related to enunciation, hearing others, and being unable to read lips as a result of mask wearing, often having to ask hospital staff to speak louder. Some participants attempted to adapt by writing down staff names as well as details to remember them by. This involved paying closer attention to their voice, body language and eyes.

I don’t mind if they have a mask on, but I had one fellow come in here and he had a hat on, goggles on, a mask on, a yellow gown and I’m like Jesus Murphy. Am I that contagious? #19 (86-year-old, female).

Loss of support from loved ones due to visitor restrictions

Participants lamented restrictive in-person visits from family and friends. As a result of reduced contact, participants found themselves having to rely on a single or select family members for caregiving and emotional support. Many struggled with this and made attempts to find other avenues of emotional support in-hospital.

I did lean more on my son. Because he’s closer in my area … He was so tired when he came with the mask yesterday and we were talking, and my hearing is not too good…It’s good to see him, but I could see he was so tired. He came straight from work yesterday. He hasn’t been home. He comes straight from work and comes to see me. #18 (92-year-old, female).

Finding other ways to feel emotionally supported

Participants described seeking comfort with the permissible communication they could have with their healthcare providers. Although this strategy was limited due to demanding staff schedules, participants appreciated brief conversations and the utilization of humor to alleviate feelings of loneliness. Participants described feeling a sense of unity and community by seeking emotional support from those caring for them.

This is something that happened, and we must live through it. I have a good place to live in. I have a fantastic family of healthcare providers. We are all together. #11 (86-year-old, female).

Staying in touch with loved ones via virtual communication

Participants described the need for virtual communication to help them stay connected to their loved ones. They highlighted phone calls as the primary method of contact, followed by texting and FaceTime. While most described these positively, a few participants described feeling nauseous on the phone and unable to figure out technology, such as Zoom.

The kids are trying to FaceTime also, but I get breathless when I talk too much. And they phone. Grandchildren they’re phoning, they’re great. We’re a close family. #14 (99-year-old, female).

Theme 3: Maintaining dignity in care

This theme, which we labled dignity in care, describes building trust, communicating with staff, and attentiveness to personhood. It was often unclear from participant narratives to what extent dignity in care was directly affected by the pandemic, partly because they lacked a reference point to discern how their end-of-life experience would have unfolded in the absence of a pandemic.

Building trust and communicating with staff

Participants described not being able to spend enough time with their healthcare providers, impeding their ability to convey their concerns. Participants expressed feelings of frustration when healthcare providers were pressed for time and unable to attend to their needs. For many patients, this was perceived as a lack of dignity, whereby they felt healthcare providers didn’t understood their vulnerability, hence undermining their sense of self. In the absence of feeling affirmed, some patients felt unworthy of their healthcare provider’s attention.

They should wait longer to see if you want to go to bed or, I need help with my legs to get on the bed. And they take off right away. Because I can sit down on the bed, but then to twist and turn and get the legs under the covers, it’s hard. They don’t do it at all unless you ask them sometimes. You’ve got to ask. They’re just busier and there’s just so much going on. Busy and they don’t want to be bothered. #16 (90-year-old, female).

Knowing and wanting to be known by healthcare providers

In the absence of families, participants wanted to know their healthcare providers on a more personal level. COVID-19 put a strain on many healthcare providers, making it challenging for them to make time for participants to know them as whole persons. Limited opportunities to know and be known impeded trusting patient-provider relationships. As a function of work demands, participants reported wanting more time from staff to communicate their health issues and assurance of their availability when needed.

The doctor stops in but he only stays a minute or two, and says, hi, how are you, and goodbye, type of thing. That’s the time, if you have any concerns you need to catch him quick to bring something up, but he does stop in, and you have that opportunity. If I had something specific, I wanted to talk to him I’d have to catch him. #17 (87-year-old, male).

Providing appropriate information

Given limited opportunity to connect with healthcare providers and the tendency for sporadic communication, participants described being unsure about the reliability of information they received and feeling things were being withheld or misrepresented. This hindered patients’ ability to make informed decisions and contribute to managing their care. This can jeoprodize dignity, by way of denying patients sufficient information to navigate their illness, or imply they are not deserving of said information.

You can tell how people[staff] are… When people are talking to you, but they’re not telling the truth, and they’re going to tell a lie…Or they get uncomfortable with something, you can notice an action. It may just be a shifting in the seat. It may be the blink. I always watch the blink. Everybody’s got a way of blinking under normal circumstances, but then when you catch them on something, the blink is… It’s a lot different. #20 (66-year-old, male).

Attentiveness to personhood

Participants noted sensitivity to care needs, attending to modesty, respecting personal identity, maintaining independence, and the hospital room environment as significant factors in safeguarding personhood. Such attentiveness led patients to feel more emotionally connected and respected by their healthcare provider, consistent with dignity conserving care (Chochinov, Citation2007).

I loved my job [as a nurse] and it was important to me. I mean they do acknowledge that… I will say they do acknowledge that I used to have a job doing that. I do credit them for that. We’ll go for a walk and they’ll ask me about that. So, that’s… I really credit them for that. #05 (60-year-old, female).

Timely attention to care needs

Participants nearing end-of-life describe the importance of timely and sensitive care as a means of upholding their sense of dignity. Participants were often satisfied with care, with their needs being met when required. At other times care needs went unmet, with a lack of attention to personal hygiene being a major concern (e.g., not being able to wash hands after using the washroom, not receiving a bath, washcloth, or towel, and not being helped in and out of bed), especially when staff were in a rush.

I know I can call, or they’ll come in at any time of the day and night and ask if they could do anything or that sort of stuff. Like this morning, I asked my nurse can you really cut my fingernails? You know, you just couldn’t get that at the hospital #03 (80-year-old, male]

Respecting bodily privacy

When relying on healthcare staff for intimate care needs (i.e., bathroom and bathing), participants describe the importance of healthcare providers respecting bodily privacy. In some instances, staff showed respect for personal boundaries, hence upholding patient dignity. Conversely, some participants described feeling berated when experiencing bathroom accidents and a loss of privacy when being washed, particularly for women with male support staff.

Privacy. I haven’t been washed I don’t know in how long. Then they often send a man and I like to wash myself, so. They take your diaper off or whatever they call that and then they give you a red cloth. And I don’t want a man to wash the front of me, I want to do it myself. #02 (98-year-old, female).

Respecting “who we were”

Participants emphasized the importance of acknowledging or affirming who they are or were as a person, and not feel diminished or compromised on the basis of dependency or illness incumbrances

Just remember who we were. Who you see sitting here in this bed is not who we were. I didn’t look like this, I was 110 pounds, I’m now on steroids so I’m 160 pounds. #05 (60-year-old, female).

Loss of independence

With waning mobility and mounting illness, participants described the experience of losing independence and having to rely on others for support. This was often described in terms of transitioning from self-reliance to having to ask others for help. In some instances, especially when resources were limited or staff burned out, this led to feelings of shame, loss of dignity and poor treatment.

Yes, there is one particular instance… During the night for some reason, I would always have to pee at night and I was still in the walking wheelchair, but yet didn’t know how to get out of it and get into the bed or whatever. And so, I called for the bedpan and I wanted to help, so I put it over on the desk, one of these night tables. I was going to do that and I dumped it all over me, the floor, the bed. So, I called and it was this guy, who was on duty and oh he was so mad… And he started pulling off my nighties, you know that you wear one backwards? And then he was trying to get the rest of the bedding off, and I’m lying there, naked, shivering. I said, could I please have a gown? Never mind the gown. He said look at the mess you made here. #9 (63-year-old, female).

Hospital room environment

Having a private, clean, noise-free, and accessible room helped safeguard participants’ sense of dignity. They described valuing having their own space, in some instances large windows, or a view of the outdoors. By contrast, others reported crowded, inaccessible, unorganized, and cluttered rooms. Crowded and disorganized rooms in some cases led to participants personal health information being placed in public areas of their rooms, raising privacy concerns.

I was there for 10 days or 11 days and barely ever saw a towel, or washcloth in the bathroom. They never… Although I can’t say it was dirty. It was not dirty. But they had no receptacles. You didn’t know which was… There was a pile here, and a pile here and you had to guess which ones were clean and which ones had been used. #06 (84-year-old, female).

Theme 4: Emotional impact of nearing death

This theme details how there were facets of approaching death that were or were not impacted by the pandemic. The former included feeling lonely, sad, and confined, along with worrying about and feeling disconnected from family members. On the other hand, challenges such as symptom distress and worries and fears regarding end-of-life seemed less closely linked to COVID-19.

Well, it’s a bit lonely because you really… You can’t have visitors up. You go out in the hallway and walk and there’s no one there. And it’s a very strange kind of feeling not to see other people walking…. I would say the last couple of weeks one of the reasons I came here and as well as pain is I’ve had a lot of anxiety in the evening time. It started at home but it carried on over to the hospital. I don’t know… I can’t pinpoint exactly what it’s about. Maybe it’s some death fears, maybe some other stuff going on. #5 (60-year-old, female).

Feeling lonely, sad, and confined

As a direct consequence of COVID-19 and visitor restriction within hospitals, participants described feeling lonely due to their inability to see children, grandchildren, spouse, and friends. Some referenced the bleak hospital environment with few people passing by in the hallways, and not being able to go outside contributing to a sense of loneliness and confinement.

Just being lonesome all the time, like yeah, I can look outside, but there’s nothing. Yeah. You know, birds if I’m lucky if I see them, you know. My daughter was going to come today … not that she ever stays long, it’s just the idea that she pops in. I feel just sad when my daughter goes home. You know, she’s part of my life. #03 (79-year-old, female).

Emotional toll of symptom distress

Independent of COVID-19, approaching death was taxing in a multitude of ways. Participants described various facets of end-of-life experience, including excessive fatigue, brain fog, anxiety, depression, and sometimes thoughts of early death.

Getting up and getting my mail and I was doing a little bit of exercise and here after it got worse, I felt that I can’t even get out of bed. I need help a lot of time. I realized that I wanted to commit suicide. #12 (87-year-old, male).

Worries and fears

As a result of COVID-19, participants expressed concerns regarding personal safety and the well-being of their families and themselves. Independent of the pandemic, patients shared fears of suffering and dying common within terminal illness.

People all around me dying and then younger children. I’ve lived a life. I’ve lived a life pretty good. It was good and everything and now we’d better watch like not to pass onto somebody else. #18 (92-year-old, female).

Theme 5: Making sense of end-of-life circumstances

This theme details how in anticipation of death, participants reflected on their ability to reason through and understand end-of-life experiences. Sub themes include, trying to process being ill, end-of-life not being as expected, feeling unable to change end-of-life circumstances, trying to “go with the flow”, and being too sick to care. While much of this was independent of COVID-19 and not unlike what is typically seen in terminally ill patients, some participants reflected on how their final days were being shaped by COVID-19 restrictions and most notably reduced time with family.

Like I’ve lived a life a little bit and I still am planning to enjoy but yes… Oh, so it’s kind of tough when I found that [cancer diagnosis] out, but I thought, what can you do? You know, you get something like that, I don’t know if there’s any hope. We didn’t travel. We were saving money to build a home for grandchildren, great-grandchildren and that. And life was wonderful, but it wasn’t quite how it was ending up and I couldn’t understand it. It was hard for me to understand where did things go. Life was so good. #18 (92-year-old, female).

Trying to process life-limiting illness

Participants reported trying to process and come to terms with life-limiting illnesses. They conveyed feeling shocked, overwhelmed, and unsure about what to expect. Some posed existential questions about why they had to suffer and were unable to recover. Given their proximity to death and the deeply personal and internal nature of these struggles, the influence of COVID-19 relative to this theme appeared limited.

People said you’ll never make five years. You made five years and now you’ve got to make six years and so I was very high and then the next day we met with our oncologist, who’s a great guy and he said, your last CT scan showed the tumours are growing. The chemo you’re on is the third line. It’s not working and it’s giving you these very bad side effects, so I think we should stop all treatment and just go into palliative care. So, within 24 hours I was at the highest point I’ve been in a long time, to the lowest point I’ve been in a long time and now I’m back in between. #21 (65-year-old, male).

End-of-life not as expected

Participants spoke about their dissatisfaction with having to spend their remaining time in a hospital. Many longed to travel or be at home with family. While COVID-19 may have hindered some of these activities (e.g., travel and visitor restrictions), this was also likely a consequence of being sick and hospitalized.

… I thought I would enjoy my cottage and I haven’t been down there now, not once this year. Once last year. That’s all. #12 (87-year-old, male).

Controlling end-of-life circumstances

Participants discussed their experiences and perceptions of controlling their end-of-life circumstances. Within this, some participants reported feeling frustrated and helpless, with many feeling unable to control their end-of-life experience. Other participants discussed adjusting and accepting their illness, including pandemic restrictions. Some participants also reported being too sick to care (i.e., dealing with severe end-of-life medical conditions overshadowed any influence of COVID-19).

This is not a hospital. This is jail. I’m going to die here. I have cancer of the brain and cancer of the left lung…I’m not coping with it. I’m just sitting here waiting. Well, I don’t know if waiting is coping. I would assume not but I can’t get proactive, not while I’m sitting here, farting in bed. #15 (63-year-old, male).

Theme 6: Coping with end-of-life

This theme details how the pandemic and approaching death were profound overlapping events for study participants. They invoked various coping strategies to navigate ongoing challenges. Subthemes within this overarching theme include gratitude and perspective taking, leaning on spirituality, finding distraction, and relying on social support. Participants also spoke of feeling unable to engage in some previously available coping methods and missing being at home. They described coping methods that allowed them to make peace or come to terms with approaching death.

Gratitude/perspective taking

Many patients shared the importance of having a positive outlook, feeling content, satisfied, and thankful. Many compared their situations with others they felt were worse off.

In the hospital. No, I think that they’ve dealt with it really well. What’s going on in the outside world, I’m sure is pretty darn difficult for people trying to live their daily lives through it. Here I’m kind of selfish… Because I’m sick, I’m kind of self-absorbed. #06 (84-year-old, female).

Relying on spirituality

Participants described the importance of spirituality and their relationship with God, indicating this was an important aspect of coping and coming to terms with end-of-life.

Like every day is a special day and I believe in God. I thank… Every morning I say, thank you for another day. I have become very, very spiritual. I am thankful that God has given me strength. I get emotional about that. #10 (83-year-old, female).

Finding distractions

Participants listed various ways of distracting themselves as a means of coping with end-of-life (e.g., television, phone, computer, tablets); others described the importance of keeping occupied with toys, games and books.

Well, try and bring things to distract yourself with. Try and learn something too. I have my iPad and I play solitaire. And I have the Silly Putty and I’m going to get some other things to fidget with. That’s all I can think of is just bring things to distract yourself. #05 (60-year-old, female).

Having social support

Patients described the importance of utilizing available social supports, including family and friends. They also spoke about the importance of visitors in preserving their mental health, even if it were a single person or care provider.

She’ll [daughter] be here Friday nights, usually. Saturday or Sunday and she can book off, like yesterday she was here. She booked off school, came around the middle of the day, had lunch with me. She bought a lunch on the way, and we had lunch. #07 (95-year-old, male).

Missing leisure activities and home environment

Although participants found ways to cope, they also described limitations in their ability to do so. Some spoke of being unable to get fresh air, walk outside, go to the gym, or volunteer. Being in hospital, and often confined to their room and not being able to go home resulted in missing various activities (e.g., gardening), their bed, and personal amenities.

Well, because I don’t belong here [hospital]. I shouldn’t be here. I need to do things at home, repair little things, walk around the garden with my wife and help her with things that now has to do herself, or have others do it. Such as little home repairs and so on. I miss that…You’re better be in your own home, in your own garden and do things everybody else does and that I miss. Lying in bed here at midday, during the day is not normal and so I miss that. #04 (88-year-old, male).

The six core sub-themes and corresponding sub-subthemes can be found in .

Many of the aforementioned themes were impacted either directly or not directly by the pandemic, as seen in .

Table A2. The six core themes with corresponding sub-themes and sub-subthemes.

Discussion

This study was designed to capture the lived experiences of palliative care inpatients during the COVID-19 pandemic. To date, research has largely focused on the perspectives of family members and healthcare providers of patients approaching death during this recent global healthcare crisis (Silvera et al., Citation2021). To redress this gap in the literature, we interviewed patients dying in the midst of COVID-19 due to any cause. Our detailed qualitative analysis saw six themes emerge, reflecting the trajectory of anticipating the need for institutional care, the experience in the hospital, and then approaching end-of-life. These include putting off going to the hospital, and how the pandemic affected time in hospital. Participants also reflected on maintaining dignity in care. Albeit not specific to COVID-19, various themes emerged related to the dying experience, including, emotional impact of nearing death, making sense of end-of-life circumstances, and coping with end-of-life.

Consistent with our findings, reductions in rates of hospitalizations for palliative care patients emerged globally during the pandemic (Guven et al., Citation2020; Stock et al., Citation2020; Wentlandt et al., Citation2021). This has seen patients and families having to navigate a difficult calculus, pitting tolerance of symptoms against fears of being separated from one another. A national study of American hospitals reported that those that enforced restricted visitation saw significant reductions in patient ratings of medical staff, responsiveness, sepsis rates and more falls (Silvera et al., Citation2021). According to families of long-term, palliative and hospice patients, strict visitation bans during end-of-life care were associated with strong emotional burden for patients and family members alike. These restrictions severely impinged on the continuity of emotional support and attention to care needs, also impacting shared decision-making toward end-of-life (Pacolli et al., Citation2022). This suggests that at the time of this study, hospital avoidance due to COVID-19 related fears was likely driven by family caregivers and patients alike. Late referral to palliative care services is associated with poorer short-term bereavement outcomes, (Wittenberg-Lyles & Sanchez-Reilly, Citation2008) underscoring the importance of interventions such as online visits or virtual therapies when conditions impede dying patients and their families being together at this critical time (Benson et al., Citation2019; Demiris et al., Citation2019).

Participants inability to see and touch loved ones compounded the emotional distress associated with end-of-life experiences. Harden et al. (Citation2020) reported three cases of severe social isolation and loneliness during the pandemic, which included an inpatient, an outpatient and a resident in an assisted living facility. Feeling isolated was sometimes compounded by PPE, and particularly wearing masks, interfering with interpersonal communication, enunciation, and an inability to identify healthcare providers. This sometimes led to what has been described as impoverished care, wherein healthcare providers weighed their obligations toward patient care against considerations of self-protection and that of their families (Chochinov et al., Citation2020).

“If the first casualty of war is truth, the first casualty of COVID-19 for patients nearing death is human dignity” (Chochinov et al., Citation2020, p. 1). Participants reported various struggles maintaining dignity and challenges associated with building trust, communication with staff and attentiveness to personhood. The latter was vulnerable and often overlooked in the wake of healthcare providers’ uncertainties surrounding viral transmission, overstretched hospital capacities, excessive workloads, disrupted PPE supplies and widespread social and economic disruptions (Pfefferbaum & North, Citation2020; Williamson et al., Citation2020). Several studies have raised the issue of healthcare provider burnout, fatigue and moral injury developing during the pandemic (Spalluto et al., Citation2020). Burnout often sees healthcare providers disengage from emotional and psychosocial facets of care, consistent with our findings regarding the importance of personhood and person-centered care. It would seem that dignity conserving strategies privileging the human side of medicine must be harmonized with public health strategies, balancing the need for safety and protection, with compassionate, person-centered palliative care (Chochinov, Citation2023; Hadler et al., Citation2023).

Coping strategies that participants engaged in, such as relying on spirituality, practicing gratitude, utilizing social supports and keeping occupied with hobbies, were also reported in a Danish study of outpatients and described as a means of maintaining a sense of control (Konradsen et al., Citation2021). While spiritual care has been described as “a deeper immunity” (Roman et al., Citation2020), most healthcare providers remained ill-equipped to offer this form of support (Mthembu et al., Citation2016). This is consistent with our findings, wherein participants identified the importance of spirituality as means of coping with end-of-life.

Study strengths and limitations

This study is unique in providing first-hand insights into the lived experience of inpatients dying during the COVID-19 pandemic. The in-depth semi-structured qualitative interviews conducted with palliative care inpatients allowed for the exploration of topics of concern not easily captured by validated measures alone. Participants were recruited from multiple healthcare institutions in Manitoba, Canada, allowing for a more holistic understanding of their lived experience. The study took place over the course of 1 year, capturing the many stages of the pandemic, thus reflecting patient experiences from when the virus was novel and a largely unknown entity, up until knowledge pertaining to transmission and vaccination became more widespread.

There are a few limitations that should be noted. First, this study did not capture the perspectives of families or healthcare providers; these were examined in independent studies, using separate and distinct recruitment strategies. While all participants were Caucasian, there was broader diversity in age, gender, religion, and illness. Moreover, although patients were informed that interviews would remain anonymous, some remained cautious with how much they shared, fearing what they said which could impact their treatment. Further, participants were receiving palliative care services from highly specialized teams with specific expertise in end-of-life care. A very large number of patients received end-of-life care on regular wards for example, or at home with family during the pandemic. We cannot assume their experiences would map perfectly onto those reported within this study.

Conclusion

The COVID-19 pandemic not only changed the way people lived, but also the way they died. Patients reported previously unimaginable distortions in care, profoundly affecting their final months, weeks and days of life. Those receiving inpatient palliative care encountered pandemic policies that affected their decisions on when to go into hospital, influenced their hospital stay, and to varying degrees, shaped their end-of-life experience. Each of these reflect the importance of human connectedness and ways in which the pandemic strained, threatened, and undermined those vital connections. In a system where human beings care for one another, it is “fitting that the human connection needed at its core was revealed to be so essential” (Silvera et al., Citation2021).

Our findings highlight the vulnerability of patients approaching death, and how the recent global pandemic accentuated that vulnerability. While infection control insists on measures based on separation and isolation, the basic human need for love, dignity, and care approaching death insists on proximity and connection. Understanding the landscape of these opposing forces is critical in shaping care for dying patients under less-than-optimal conditions. Insights gleaned from this study offer critical guidance for future pandemic planning or equivolent global healthcare crisises, helping shape strategies for the care of those nearing death.

Ethical approval

The University of Manitoba’s Health Research Ethics Board approved this study (HS24291, H2020:423).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.2 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Barrett, K., Khan, Y. A., Mac, S., Ximenes, R., Naimark, D. M. J., & Sander, B. (2020). Estimation of COVID-19–induced depletion of hospital resources in Ontario, Canada. CMAJ: Canadian Medical Association Journal = Journal de L’Association Medicale Canadienne, 192(24), E640–E646. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.200715

- Benson, J. J., Oliver, D. P., Washington, K. T., Rolbiecki, A. J., Lombardo, C. B., Garza, J. E., & Demiris, G. (2019). Online social support groups for informal caregivers of hospice patients with cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing: The Official Journal of European Oncology Nursing Society, 44, 101698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejon.2019.101698

- Black, A., McGlinchey, T., Gambles, M., Ellershaw, J., & Mayland, C. R. (2018). The “lived experience” of palliative care patients in one acute hospital setting - A qualitative study. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 91. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0345-x

- Bradshaw, A., Dunleavy, L., Garner, I., Preston, N., Bajwah, S., Cripps, R., Fraser, L. K., Maddocks, M., Hocaoglu, M., Murtagh, F. E. M., Oluyase, A. O., Sleeman, K. E., Higginson, I. J., & Walshe, C. (2022). Experiences of staff providing specialist palliative care during COVID-19: A multiple qualitative case study. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine, 115(6), 220–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/01410768221077366

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., Hayfield, N., & Terry, G. (2019). Thematic analysis. https://link.springer.com/referenceworkentry/10.1007/978-981-10-5251-4_103

- Chochinov, H. M. (2007). Dignity and the essence of medicine: The A, B, C, and D of dignity conserving care. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 335(7612), 184–187. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.39244.650926.47

- Chochinov, H. M. (2023). Intensive caring: Reminding patients they matter. 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1200/JCO.23.00042

- Chochinov, H. M., Bolton, J., & Sareen, J. (2020). Death, dying, and dignity in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 23(10), 1294–1295. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2020.0406

- Chochinov, H. M., Hack, T., McClement, S., Harlos, M., & Kristjanson, L. (2002). Dignity in the terminally ill: A developing empirical model. Social Science and Medicine, 54, 433–443.

- Ciemins, E. L., Brant, J., Kersten, D., Mullette, E., & Dickerson, D. (2015). A qualitative analysis of patient and family perspectives of palliative care. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 18(3), 282–285. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2014.0155

- Demiris, G., Oliver, D. P., Washington, K., & Pike, K. (2019). A problem-solving intervention for hospice family caregivers: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 67(7), 1345–1352. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15894

- Dennis, B., Vanstone, M., Swinton, M., Brandt Vegas, D., Dionne, J. C., Cheung, A., Clarke, F. J., Hoad, N., Boyle, A., Huynh, J., Toledo, F., Soth, M., Neville, T. H., Fiest, K., & Cook, D. J. (2022). Sacrifice and solidarity: A qualitative study of family experiences of death and bereavement in critical care settings during the pandemic. BMJ Open, 12(1), e058768. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-058768

- Donnelly, S., Prizeman, G., Coimín, D., Korn, B., & Hynes, G. (2018). Voices that matter: End-of-life care in two acute hospitals from the perspective of bereaved relatives. BMC Palliative Care, 17(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-018-0365-6

- Ersek, M., Smith, D., Griffin, H., Carpenter, J. G., Feder, S. L., Shreve, S. T., Nelson, F. X., Kinder, D., Thorpe, J. M., & Kutney-Lee, A. (2021). End-of-life care in the time of COVID-19: Communication matters more than ever. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(2), 213–222.e2. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.024

- Fish, E. C., & Lloyd, A. (2022). Moral distress amongst palliative care doctors working during the COVID-19 pandemic: A narrative-focussed interview study. Palliative Medicine, 36(6), 955–963. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221088930

- Galchutt, P. (2022). Transforming spiritual care. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC, 76(1), 73–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/15423050221079563

- Gergerich, E., Mallonee, J., Gherardi, S., Kale-Cheever, M., & Duga, F. (2021). Strengths and struggles for families involved in hospice care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Social Work in End-of-Life & Palliative Care, 17(2-3), 198–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/15524256.2020.1845907

- Guan, W., Liang, W., He, J., & Zhong, N. (2020). Cardiovascular comorbidity and its impact on patients with COVID-19. European Respiratory Journal, 55(6), 2001227. https://doi.org/10.1183/13993003.01227-2020

- Guven, D. C., Aktas, B. Y., Aksun, M. S., Ucgul, E., Sahin, T. K., Yildirim, H. C., Guner, G., Kertmen, N., Dizdar, O., Kilickap, S., Aksoy, S., Yalcin, S., Turker, A., Uckun, F. M., & Arik, Z. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic: Changes in cancer admissions. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002468

- Hadler, R. A., Weeks, S., Rosa, W. E., Choate, S., Goldshore, M., Julião, M., Mergler, B., Nelson, J., Soodalter, J., Zhuang, C., & Chochinov, H. M. (2023). Top ten tips palliative care clinicians should know about dignity-conserving practice. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 27(4), 537–544. https://doi.org/10.1089/jpm.2023.0544

- Hanna, J. R., Rapa, E., Dalton, L. J., Hughes, R., McGlinchey, T., Bennett, K. M., Donnellan, W. J., Mason, S. R., & Mayland, C. R. (2021). A qualitative study of bereaved relatives’ end of life experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Palliative Medicine, 35(5), 843–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163211004210

- Hansen, T., Sevenius Nilsen, T., Knapstad, M., Skirbekk, V., Skogen, J., Vedaa, Ø., & Nes, R. B. (2022). Covid-fatigued? A longitudinal study of Norwegian older adults’ psychosocial well-being before and during early and later stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. European Journal of Ageing, 19(3), 463–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-021-00648-0

- Harden, K., Price, D. M., Mason, H., & Bigelow, A. (2020). COVID-19 shines a spotlight on the age-old problem of social isolation. Journal of Hospice and Palliative Nursing: JHPN: The Official Journal of the Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, 22(6), 435–441. https://doi.org/10.1097/NJH.0000000000000693

- Hetherington, L., Johnston, B., Kotronoulas, G., Finlay, F., Keeley, P., & McKeown, A. (2020). COVID-19 and hospital palliative care – A service evaluation exploring the symptoms and outcomes of 186 patients and the impact of the pandemic on specialist Hospital Palliative Care. Palliative Medicine, 34(9), 1256–1262. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216320949786

- Ho, F., Lau, F., Downing, M. G., & Lesperance, M. (2008). A reliability and validity study of the Palliative Performance Scale. BMC Palliative Care, 7(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-684X-7-10

- Kates, J., Gerolamo, A., & Pogorzelska-Maziarz, M. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on the hospice and palliative care workforce. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 38(3), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12827

- Konradsen, H., True, T. S., Vedsegaard, H. W., Wind, G., & Marsaa, K. (2021). Maintaining control: A qualitative study of being a patient in need of specialized palliative care during the COVID-19 pandemic. Progress in Palliative Care, 29(4), 186–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/09699260.2021.1872139

- Lopez, S., Finuf, K. D., Marziliano, A., Sinvani, L., & Burns, E. A. (2021). Palliative care consultation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A retrospective study of characteristics, outcomes, and unmet needs. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(2), 267–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.015

- Mahase, E. (2020). Covid-19: WHO declares pandemic because of “alarming levels” of spread, severity, and inaction. BMJ (Clinical Research ed.), 368, m1036. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1036

- Manitoba. (2022). Provincial respiratory surveillance report. https://www.gov.mb.ca/health/publichealth/surveillance/covid-19/2022/week_17/index.html

- Moriyama, D., Scherer, J. S., Sullivan, R., Lowy, J., & Berger, J. T. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 surge on clinical palliative care: A descriptive study from a New York hospital system. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 61(3), e1–e5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.12.011

- Mthembu, T. G., Wegner, L., & Roman, N. V. (2016). Teaching spirituality and spiritual care in health sciences education: A systematic review. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences, 22(1), 1036–1057. http://hdl/handle.net/10520/EJC200068

- Muehlhausen, B. L., Desjardins, C. M., Chappelle, C., Schwartzman, G., Tata-Mbeng, B., & Fitchett, G. (2022). Managing spiritual care departments during the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. The Journal of Pastoral Care & Counseling: JPCC, 76(4), 294–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/15423050221122029

- Pacolli, L., Wahidie, D., Erdogdu, I. Ö., Yilmaz-Aslan, Y., & Brzoska, P. (2022). Strategies addressing the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic in long-term, palliative and hospice care: A qualitative study on the perspectives of Patients’ family members. Reports, 5(3), 26. https://doi.org/10.3390/reports5030026

- Pankratz, L., Gill, G., Pirzada, S., Papineau, K., Reynolds, K., Riviere, C. L., Bolton, J. M., Hensel, J. M., Olafson, K., Kredentser, M. S., El-Gabalawy, R., Hiebert, T., & Chochinov, H. M. (2023). “It took so much of the humanness away”: Health care professional experiences providing care to dying patients during COVID-19. Death Studies, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2023.2266639

- Pauli, B., Strupp, J., Schloesser, K., Voltz, R., Jung, N., Leisse, C., Bausewein, C., Pralong, A., & Simon, S. T, PallPan consortium. (2022). It’s like standing in front of a prison fence – Dying during the SARS-CoV2 pandemic: A qualitative study of bereaved relatives’ experiences. Palliative Medicine, 36(4), 708–716. https://doi.org/10.1177/02692163221076355

- Pfefferbaum, B., & North, C. (2020). Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. The New England Journal of Medicine, 383(6), 510–512. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2013466

- Rodríguez-Prat, A., Monforte-Royo, C., Porta-Sales, J., Escribano, X., & Balaguer, A. (2016). Patient perspectives of dignity, autonomy and control at the end of life: Systematic review and meta-ethnography. PloS One, 11(3), e0151435. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0151435

- Roman, N. V., Mthembu, T. G., Hoosen, M., & Roman, N. (2020). Spiritual care – ‘A deeper immunity’ – A response to Covid-19 pandemic. African Journal of Primary Health Care and Medicine, 12(1), 2071–2928. https://doi.org/10.4102/phcfm.v12i1.2456

- Rowe, J. G., Potts, M., McGhie, R., Dinh, A., Engel, I., England, K., & Sinclair, C. T. (2021). Palliative care practice during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A descriptive qualitative study of palliative care clinicians. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(6), 1111–1116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.06.013

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 905–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253488

- Schallenburger, M., Reuters, M. C., Schwartz, J., Fischer, M., Roch, C., Werner, L., Bausewein, C., Simon, S. T., van Oorschot, B., & Neukirchen, M. (2022). Inpatient generalist palliative care during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic – experiences, challenges and potential solutions from the perspective of health care workers. BMC Palliative Care, 21(1), 63. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-022-00958-9

- Silvera, G. A., Wolf, J. A., Stanowski, A., & Studer, Q. (2021). The influence of COVID-19 visitation restrictions on patient experience and safety outcomes: A critical role for subjective advocates. Patient Experience Journal, 8(1), 30–39. https://doi.org/10.35680/2372-0247.1596

- Spalluto, L. B., Planz, V. B., Stokes, L. S., Pierce, R., Aronoff, D. M., Mcpheeters, M. L., & Omary, R. A. (2020). Transparency and trust during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2020.04.026

- Stock, L., Brown, M., & Bradley, G. (2020). First do no harm with COVID-19: Corona collateral damage syndrome. The Western Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(4), 746–747. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2020.5.48013

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Van Orden, K. A., Witte, T. K., Cukrowicz, K. C., Braithwaite, S. R., Selby, E. A., & Joiner, T. E. (2010). The interpersonal theory of suicide. Psychological Review, 117(2), 575–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018697

- Wallace, C. L., Wladkowski, S. P., Gibson, A., & White, P. (2020). Grief during the COVID-19 pandemic: Considerations for palliative care providers. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 60(1), e70–e76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.04.012

- Wentlandt, K., Cook, R., Morgan, M., Nowell, A., Kaya, E., & Zimmermann, C. (2021). Palliative care in Toronto during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management, 62(3), 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2021.01.137

- Williamson, V., Murphy, D., & Greenberg, N. (2020). COVID-19 and experiences of moral injury in front-line key workers. Occupational Medicine (Oxford, England), 70(5), 317–319. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqaa052

- Wittenberg-Lyles, E. M., & Sanchez-Reilly, S. (2008). Palliative care for elderly patients with advanced cancer: A long-term intervention for end-of-life care. Patient Education and Counseling, 71(3), 351–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pec.2008.02.023

- Xu, J., Yang, X., Yang, L., Zou, X., Wang, Y., Wu, Y., Zhou, T., Yuan, Y., Qi, H., Fu, S., Liu, H., Xia, J., Xu, Z., Yu, Y., Li, R., Ouyang, Y., Wang, R., Ren, L., Hu, Y., … Shang, Y. (2020). Clinical course and predictors of 60-day mortality in 239 critically ill patients with COVID-19: A multicenter retrospective study from Wuhan, China. Critical Care, 24(1), 394. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-03098-9

- Yang, G. M., Ewing, G., & Booth, S. (2012). What is the role of specialist palliative care in an acute hospital setting? A qualitative study exploring views of patients and carers. Palliative Medicine, 26(8), 1011–1017. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269216311425097

Appendix 1.

Interview framework

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected the way you are coping with your illness?

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your care?

The COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in policies that include limited visitors (for patients in institutional settings), physical distancing and the use of personal protective equipment (PPE). How have these policies affected your care and how you feel about your care?

For most people who are ill, being treated with dignity means feeling that others understand and appreciate who they are as a person. Has the pandemic affected your sense of being treated with dignity? Please provide examples of when you felt dignity was supported and when you felt it was not.

What have you learned from your experience of being ill at this time (i.e. in the midst of a pandemic) that you would like to pass along to other patients, families and/or healthcare providers?