Abstract

Parental suicide in childhood increases the risk of mental ill-health, substance use and premature mortality, particularly through suicide. Postvention supports tailored to the well-being and functioning of suicide-bereaved children and their remaining parents are thus of critical importance to counteract negative development. This explorative cross-sectional study seeks clinically relevant knowledge by investigating posttraumatic stress (PTS), sense of coherence (SOC) and family functioning among children (n = 22), adolescents (n = 18) and parents (n = 40) before their attendance at a family-based grief support program. The results demonstrate critical health outcomes for children and parents, and in particular for adolescents. Clinically relevant symptoms of PTS were found in 36% of children, 65% of adolescents, and 37% of parents. All groups showed lower SOC than the norm. Adolescents reported dysfunctional family functioning for the dimensions Communication and Affective Responsiveness. Psychoeducational and trauma-informed support is recommended where family communication and meaning construction of suicide is given special attention.

A significant body of research has established a link between experience of parental suicide in childhood and the subsequent development of mental health challenges and social difficulties in bereaved children and adolescents throughout their life course. This is primarily evident in the manifestation of psychiatric conditions, such as depression, anxiety, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as impaired social adjustment and increased rates of alcohol and drug use (Andriessen et al., Citation2016; Cerel & Aldrich, Citation2011). These outcomes are mainly assessed through self-reporting compared to the general population and other groups of young parentally bereaved. In addition, a significantly heightened risk of suicide has been established among these young mourners in two systematic reviews (Del Carpio et al., Citation2021; Hua et al., Citation2019). Swedish register studies underscore an increased likelihood of hospitalization for mental health issues, primarily anxiety, depression, and suicidality, as well as substance use (Hjern et al., Citation2014). These analyses highlight a heightened risk of premature mortality, predominantly attributed to preventable causes such as accidents, addiction, violence, and notably, suicide (Hjern et al., Citation2014). It is therefore crucial to recognize suicide-bereaved children as a risk group for negative health outcomes extending into adulthood.

Qualitative research on the experiences of children and young people coping with parental suicide highlights the unique challenges they often face. These challenges include grappling with why their parent ended their life, a circumstance that frequently triggers self-critical responses in the form of self-blame and shame (Schreiber et al., Citation2017; Silvén Hagström, Citation2019). In addition, studies on family functioning and relationships before parental suicide reveal that suicide-bereaved children may bear the burden of preexisting family dysfunction, rejection, and trauma, which can further complicate the grieving process (Andriessen et al., Citation2016; Cerel et al., Citation2008). Moreover, suicide-bereaved families recurrently report how societal stigma surrounding suicide adds another layer of complexity to their grief, often hindering their access to empathy and support (Cerel et al., Citation2008; Silvén Hagström, Citation2021). The impact of the grief of the remaining parent is also a crucial aspect as it significantly affects the support system for the bereaved child. Research on the post-loss characteristics of suicide-bereaved families reveals that the remaining parent, who often plays a pivotal role in providing emotional stability and support, is not only grappling with profound loss but also at an elevated risk of developing mental health issues (Andriessen et al., Citation2016). Moreover, widows with younger children may experience depression, anxiety, and PTS (Falk et al., Citation2021), as well as suicidal thoughts following a spouse’s death (Erlangsen et al., Citation2017). These circumstances can limit the parent’s capacity to engage in child-focused communication and support. Furthermore, the aftermath of suicide can trigger family conflict, perpetuate taboos, and result in a reluctance to address the topic, thereby compromising overall family cohesion (Creuzé et al., Citation2022). In the absence of sufficient information and support, grieving children find themselves in a vulnerable position and professional intervention becomes paramount.

While the above research suggests that children’s grieving process is influenced by family history, parenting skills, and current family context, there is limited understanding of suicide bereaved children’s, adolescents’ and parents’ well-being and functioning during their help-seeking phase. This is critical knowledge for a better understanding of how postvention supports can effectively align with their specific conditions and needs. The primary objective of this study is to contribute clinically relevant knowledge in this regard. The study builds on prior research highlighting the heightened prevalence of posttraumatic stress in children bereaved by parental suicide (Andriessen et al., Citation2016; Cerel & Aldrich, Citation2011). Its findings indicate the intergenerational transmission of posttraumatic stress derived from parents’ exposure to trauma, stress levels, caregiving capacity, and overall family functioning (Telman et al., Citation2016). Acknowledging the positive association between communication and meaning-making processes and perceived sense of coherence as a protective factor in grief (Boelen & O’Connor, Citation2022; Delgado et al., Citation2023; Leung et al., Citation2022), the components of sense of coherence (SOC) – comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness – also serve as pertinent outcome measures. Consequently, the main aim of this study is to explore self-reported posttraumatic stress (PTS), SOC and family functioning among children, adolescents, and parents prior to their participation in a grief support program for families affected by a parent’s suicide.

Materials and methods

Participants and procedure

The participants were recruited through a grief support program organized by a Swedish nonprofit children’s rights organization (Silvén Hagström, Citation2021). In all, 40 suicide-bereaved families were invited and agreed to participate in this study between 2017 and 2021. With the exception of five children who did not participate in the grief support program, all the family members chose to participate in the study. Parents and children were informed separately about the study using age-appropriate invitations. Both parents and children had to give written informed consent to participate. Parental consent was also required for participating children under the age of 18. The 40 families provided data by filling out a questionnaire in connection with their arrival at the support program. Participants represented three respondent groups: children aged 8–11 years, n = 22 (12 girls and 10 boys); adolescents aged 12–19 years, n = 18 (10 girls and 8 boys); and remaining parents, n = 40 (35 mothers and 5 fathers). A support group leader was available to assist each family with completing the questionnaire, if needed. A majority of the remaining parents reported higher or university education and represented a “white middle class” population, while a minority of parents had more limited educational backgrounds and/or were of other ethnicities. More than half the parents had co-resided with the deceased parent before the suicide. A majority lived with their children as single parents after the suicide, while a few had entered new partner relationships before or after the suicide. For a more detailed description of the participant characteristics, see .

Table 1. Characteristics of the study sample.

The original study design involved two follow-up assessments after the initial assessment, conducted immediately before participation. These follow-ups were intended to assess the effect of the grief support program: the first one month and the second six months post-participation. Unfortunately, the small sample size and drop-out at follow-up by some participants meant that reliable analyses of effect were not possible. However, an assessment of the perceived meaningfulness and impact of the grief support program was conducted through a narrative evaluation (Silvén Hagström, Citation2021). This current study was reviewed and approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Uppsala, Sweden (Id. 2015/504).

Assessments

Posttraumatic stress

The Impact of Events Scale Revised (IES-R) (Horowitz et al., Citation1979; Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997) was used to assess symptoms of posttraumatic stress (PTS) in the past seven days. This scale comprises eight intrusion symptoms, eight avoidance symptoms and six hypervigilance symptoms, giving a total of 22 items. Each item is scored on a scale of 0 to 4. The total scale score ranges from 0 to 88. Mean values equal to or greater than the cutoff of 1.89 on a subscale and 1.8 on the total scale are suggested to denote clinically relevant symptoms (Weiss & Marmar, Citation1997). The Swedish version of the IES-R has proved to be a sound measure of symptoms of posttraumatic stress, with good discriminant validity based on the IES-R total score (Arnberg et al., Citation2014; Sveen et al., Citation2010). In the current study, the internal consistency of the measure, as calculated using Cronbach’s alpha, was high for both parents and adolescents (0.95 and 0.93, respectively).

The children under the age of 12 answered the Children’s Impact of Events Scale (8) (CRIES-8) (Perrin et al., Citation2005). CRIES-8 comprises eight items measuring intrusion and avoidance (4 items each) in the past seven days in relation to a stressful life event. Each item is scored on a 4-point scale, ranging from ‘not at all’ to ‘often.’ The scores rage from 0 to 40. In accordance with previous studies on various populations (Perrin et al., Citation2005), a total score ≥ 17 was used to denote clinically relevant symptoms of PTS. Cronbach’s alpha for the CRIES was high (0.87).

Sense of coherence

Derived from Antonovsky’s salutogenic theory (Antonovsky, Citation2001), sense of coherence can be viewed as a measure of health, but can also be looked on as the ability to cope with stressful events (Eriksson & Lindström, Citation2005). Thus, SOC reflects a person’s resources and dispositional orientation that enable him or her to manage tension, reflect on internal and external resources, and deal with stressors in a health-promoting manner. A 13-item sense of coherence scale (SOC-13) is used to measure SOC based on three fundamental elements: Comprehensibility (5 items), Manageability (4 items) and Meaningfulness (4 items) (Antonovsky, Citation2001). Items are assessed on a 7-point scale to give a total score that ranges from 13 to 91. Scores of under 60 are indicative of a low SOC, of 61 to 75 of a moderate SOC and above 75 of a high SOC. The SOC-13 has been shown to be a reliable, valid and cross culturally applicable instrument (Eriksson & Lindström, Citation2005). Cronbach’s alphas were high for both adolescents (0.77) and parents (0.78).

In the children under the age of 12, SOC was assessed using the child-adapted version, ‘How do I feel?’ (Margalit, Citation1998). This scale comprises 19 items, three of which are ‘diversion’ questions that should be easy for the child to answer and are not included in the analysis. The remaining statements assess Comprehensibility (5 items), Manageability (7 items), and Meaningfulness (4 items). The total score ranges from 16 to 64 and higher scores indicate a higher SOC (Margalit, Citation1998). The Cronbach’s alpha for the scale was low (0.42).

Family functioning

Family functioning was assessed using the McMaster Family Assessment Device (FAD), which consists of 60 items on seven dimensions of family functioning: Problem solving (6 items), Communication (9 items), Roles (11 items), Affective responsiveness (6 items), Affective involvement (7 items), Behavior control (9 items) and General functioning (12 items) (Epstein et al., Citation1983). The children and adolescents filled out a shortened version of the FAD to reduce respondent burden. Specifically, the children and adolescents were assessed on the 27 items under Communication, Affective responsiveness, and General functioning.

Each item was answered on a scale of 1 (totally disagree) to 4 (totally agree). A low score on the scale indicates a healthy family climate while a high score represents a dysfunctional family climate. The following cutoff scores were used for each dimension to denote dysfunctional family functioning: General functioning, a score of ≥ 2.00; Roles, ≥ 2.30; Communication/Problem solving/Affective responsiveness, ≥2.20; Affective involvement, ≥ 2.10; and Behavior control, ≥1.90 (Epstein et al., Citation1983). The Cronbach’s alphas for both the full and the adapted versions were high (parents, 0.90; adolescents, 0.94; and children, 0.89).

Statistical analyses

Analyses of the responses of the three groups – children, adolescents and remaining parents– were performed separately. All the analyses were based on valid responses, i.e., only complete answers with no imputation of missing data, and conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 28 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). A two-sided P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Descriptive analyses were used to describe the demographic characteristics of the participants and to summarize the results of each outcome measure, with an emphasis on the proportion of individuals with clinically relevant symptoms of PTS, low SOC and dysfunctional family functioning according to the cutoff values. For the SOC-13 scale, the Student’s t-test was used to compare the group means of our respondent groups with norm group mean data from previous data sets (Langius & Björvell, Citation1993; Margalit, Citation1998; Nilsson et al., Citation2003; Räty et al., Citation2003). The Pearson correlation coefficient and paired t-tests were used to assess the correspondence of mean scores of the outcome measures.

Results

Posttraumatic stress

Clinically significant symptoms of PTS were reported by 36% (n = 8) of children and 65% (n = 11) of adolescents (). The group mean value for the children was 17.1 (SD = 11), which denotes clinically relevant symptoms of PTS according to the clinical cutoff for the CRIES-8 measure (see ) (Perrin et al., Citation2005). The adolescents reported mean values on the avoidance and hypervigilance subscales above the cutoff of 1.89, while the mean value for intrusion did not denote clinically significant levels of symptoms ().

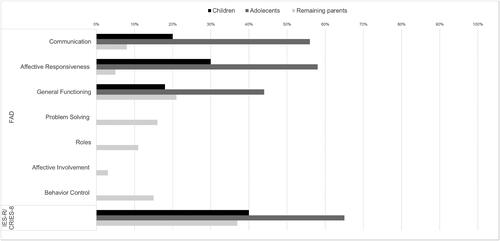

Figure 1. Proportion of children, adolescents and remaining parents who report above the cutoff indicative of dysfunctional family functioning in each dimesion of the FAD measure as well as clinically relevant symptoms of PTS according to cutoff scores of the IES-R (parents and adolescents) and CRIES-8 (children).

Table 2. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children, adolescents and remaining parents according to CRIES-8 (children) and IES-R (adolescents and parents), respectively.

Overall, 37% (n = 14) of the parents reported clinically relevant symptoms of PTS (). The highest proportion of clinically relevant symptoms of PTS was found for the intrusion subscale, where almost half of parents reported symptoms above the cutoff (, n = 18; 45%). As a group, parents reported symptoms of PTS below clinical cutoffs on all subscales of the IES-R.

Sense of coherence

The SOC outcomes for all the respondent groups are presented in . The mean value for the children (n = 20, M = 42.4, SD = 3.9) was significantly lower than that of the norm group of children aged 9 years old (n = 76, M = 48.7, SD = 5.7; t(94) = 4.655, P < 0.001) (Margalit, Citation1998). Similarly, the mean value for the adolescents (n = 18, M = 55.4, SD = 10.7) was significantly lower than Swedish norm data (M = 61) and control data from a previous study on adolescents performed in Sweden (n = 282, M = 63.7, SD = 12.1; t(298) = 2.839, P = 0.005) (Räty et al., Citation2003). The majority of adolescents (n = 12; 67%) reported low SOC, about a quarter (n = 5; 28%) moderate SOC and one adolescent reported high SOC.

Table 3. Sense of coherence (SOC)Table Footnotea of children, adolescents and remaining parents.

Remaining parents (n = 40, M = 57.4, SD = 11.1) reported significantly lower SOC than Swedish norm data (n = 145, M = 61, SD = 9, t(183) = 2.125, P = 0.035) (Langius & Björvell, Citation1993). The majority of the remaining parents (n = 24; 60%) reported low SOC, about one-third (n = 14; 35%) moderate SOC and two parents (5%) reported high SOC.

Family functioning

The proportion of children who reported values over the cutoff for each dimension of family functioning, which denotes dysfunctional functioning, was 18% (General functioning), 20% (Communication), and 30% (Affective responsiveness) (). The mean values for all three dimensions reported by the children were lower than the cutoff scores (Epstein, Bishop & Levin, Citation1978; Epstein et al., Citation1983).

The proportion of adolescents who reported values over the cutoff for each dimension of family functioning was 18% (General functioning), 20% (Communication), and 30% (Affective responsiveness) (). However, the mean values for Communication and Affective responsiveness as answered by adolescents were above cutoff scores, indicative of dysfunctional family functioning in these dimensions (). Two children and six adolescents reported dysfunctional family functioning in all three dimensions, and four children and five adolescents in two out of the three dimensions.

Table 4. Family functioning as reported by children, adolescents and remaining parents.

Among the remaining parents, the proportion reporting values over the cutoff ranged from 3% (n = 1) for the Affective involvement dimension to 21% (n = 8) for General functioning, (). As a group, parents reported lower mean values than the cutoff scores in all the dimensions.

Cross-sectional analyses of outcomes: Children and adolescents

Children who reported dysfunction in Communication reported statistically significantly lower SOC than children below the cutoff for Communication (M = 39; SD = 4 vs. M = 44: SD = 3; t(18) = 44.439, P < 0.001). The children’s reports on SOC showed a strongly negative correlation with the family functioning dimensions Communication (r(19) = –0.72, P < 0.001) and Affective responsiveness (r(17) = –0.67, P = 0.003). Similarly, children who reported dysfunction in the Affective responsiveness dimension reported statistically significantly lower SOC than children below the cutoff for Affective responsiveness (M = 39; SD = 4 vs. M = 44: SD = 4; t(16) = 40.667, P < 0.001). Moreover, a moderate to strong positive correlation was found between PTS and the family functioning dimension General functioning (r(19) = 0.62, P = 0.004).

A strongly negative correlation was found between adolescents’ reports of SOC and all dimensions of family functioning (Communication: r(18) = –0.68, P = 0.002; Affective responsiveness: r(17)–0.71, P = 0.002; General functioning: r(17)–0.65, P = 0.005). Adolescents who reported family dysfunction reported statistically significantly lower SOC than adolescents below the cutoffs (Communication: M = 50, SD = 9 vs. M = 63, SD = 9, t(17) = 21.085, P < 0.001; Affective responsiveness: M = 49, SD = 9 vs. M = 62, t(16) = 19.911, P < 0.001; General functioning: M = 51; SD = 10 vs. M = 60, SD = 10, t(16) = 20.253, P < 0.001). Moreover, we found a moderately negative correlation in the adolescents (r(17) = –0.57, P = 0.017) between SOC and PTS. Of the adolescents with low SOC, 75% (n = 9) reported clinical symptoms of PTS. Half the adolescents (n = 2; 50%) with moderate SOC reported PTS above the clinical cutoff, while the adolescents reporting high SOC were below the clinical cutoff for PTS. No statistically significant correlation was found for adolescents’ reports of family functioning and PTS.

There was a strongly negative correlation (r(38) = –0.70, P < 0.001) between SOC and PTS for the remaining parents. Of those with low SOC, 59% (n = 13) reported clinically relevant symptoms of PTS. The corresponding proportion for parents with moderate SOC was 7% (n = 1). No statistically significant correlation was found between either family functioning or SOC and PTS.

Discussion

The study investigated self-reported PTS, SOC and family functioning in children, adolescents, and remaining parents prior to their participation in a grief support program for families affected by a parent’s suicide. About one-third of the children, two-thirds of the adolescents and two-fifths of the remaining parents reported clinically relevant symptoms of PTS. This highlights a notably high incidence of PTS across all groups, with adolescents emerging as particularly vulnerable. These findings align with a study by Pfeffer et al. (Citation2002), which investigated anxiety and depression levels in suicide-bereaved children and adolescents on their enrollment in a family-based grief support program. In that case, however, the sample had undergone screening to exclude psychiatric morbidity, a procedure not implemented in the current study. The estimates of PTS correlated with self-reported SOC, with results for all respondents showing lower SOC than norm data. While a correlation between PTS and SOC has been demonstrated following various types of events (Schäfer et al., Citation2019), to our knowledge, this relationship has not been investigated in the specific context of family suicide bereavement. Prior investigations have also confirmed a correlation between low SOC in parents and a parallel decrease in SOC in their children, especially as the children mature (Leung et al., Citation2022). This implies that parents may find it difficult to instill comprehension, manageability, and meaningfulness in their children when essential resources are lacking. The reporting by children and parents overall denoted healthy family functioning, while the adolescents, and particularly those with clinical symptoms of PTS and low SOC, reported dysfunctional functioning concerning Communication and Affective responsiveness. This correlation further underscores the impact of parents’ constrained resources on the children’s resilience and health. Collectively, these findings suggest that a significant proportion of all the respondent groups experienced poor well-being and functioning to an extent that calls for early intervention and professional support.

The elevated levels of self-reported PTS identified, coupled with perceived low SOC and deficits in responsiveness and communication, underscore serious concerns, although these findings are not unexpected. Families bereaved by suicide frequently grapple with preexisting mental health challenges and social issues, along with heightened levels of stress and dysfunctional familial dynamics (Andriessen et al., Citation2016; Cerel et al., Citation2008). Moreover, a significant number of parents in this study assumed the role of single parent following the suicide, which entails a transition to more extensive caring responsibilities and an accompanying increase in parenting-related stress. Additionally, there is a prevailing argument regarding the scarcity of support services available to both young mourners and their parents (Wilson & Marshall, Citation2010), and most families had not received any suicide-specific support in connection with the parental loss. Furthermore, the detrimental impact of stigmatizing responses to suicide, which are characterized by insecurity, avoidance, distorted communication, blame, and unhelpful advice, often contributes to impaired social interactions (Feigelman et al., Citation2009). This, in turn, results in grieving families frequently encountering restricted access to social support (Kaspersen et al., Citation2022). Given that children heavily depend on their parents to navigate the grieving process, the findings of the current study emphasize the imperative of early identification and the provision of grief support to families affected by suicide. Such timely and accessible grief assistance with a low threshold shows promise in mitigating barriers to communication and parental support, thereby facilitating the family’s processing of a traumatic parental loss (Bergman et al., Citation2017).

The findings call for implementation of psycho-educational and trauma-informed interventions tailored to help suicide-bereaved family members comprehend and manage parental loss. Moreover, these results underscore the critical importance of family-oriented support to strengthen the coping abilities of the family system, promote open communication, and facilitate meaning construction. However, it is essential to recognize that support does not have to be limited to family counseling. Suicide-bereaved adolescents often prefer not to participate in grief therapy with their parents. Instead, they desire psycho-educational support in a safe professional environment that validates and normalizes their grief experiences and enhances their coping skills (Andriessen et al., Citation2022; Ross et al., Citation2021). This could be facilitated in a professionally led peer group setting, complemented by family conversations or exercises to foster communication and support within the family regarding the specific loss. For instance, family activities could be designed to support the shared construction of memories of the deceased parent and meaning construction of suicide (Winchester Nadeau, Citation2001). In addition, in such a professional context, it could be beneficial to educate parents about children’s grief responses and needs following a parental suicide, while also enhancing their capacity to provide emotional support (Ross et al., Citation2021). Ultimately, integrating individual processing into a family approach to suicide-bereavement is believed to have the potential to enhance the comprehensibility, manageability, and meaningfulness of the grieving process among both parents and children. This approach would aim to mitigate complicated grief and promote posttraumatic growth (Delgado et al., Citation2023; Neimeyer et al., Citation2014). Finally, given the risks of polyvictimization, trauma-informed support must extend beyond parental suicide to include evaluation of other traumatic experiences (Telman et al., Citation2016). While individualized trauma support may be needed, there is promising evidence to suggest that adding a parental component to individual trauma treatment can improve outcomes for children with posttraumatic stress symptoms (Mavranezouli et al., Citation2020). Family-based cognitive-behavioral therapy, taking a psychoeducational approach, also shows promise in addressing ineffective beliefs linked to complicated grief and suicidal ideation in suicide-bereaved family members (de Groot et al., Citation2010).

The study’s findings should be interpreted with several limitations in mind. A high proportion of participants came from well-educated families, potentially introducing socioeconomic bias. Participant selection was linked to participation in a grief support program, potentially excluding voices from less advantaged families. The small sample size and the predominance of father loss to suicide also limit generalizability. Future research should address these limitations by expanding participant numbers and ensuring greater diversity. Despite the IES-R measure’s good diagnostic utility, particularly in monitoring internal experiences of health and distress in children as young as 6 or 7 (Adkins et al., Citation2008), reliance on self-reporting could introduce response bias (Roseman et al., Citation2016). Self-reporting in this study served as a screening tool rather than a diagnostic instrument. The low Cronbach’s alpha of the child-adapted version of SOC, How do I feel, raises concerns about its suitability. Larger studies are needed to determine the psychometric properties of this scale. Finally, the effectiveness of the support program was not assessed in this study. Future longitudinal studies are encouraged to evaluate the impact of accessible support resources on suicide-bereaved families.

The findings underscore the vulnerability of families bereaved by parental suicide, accentuating the critical need for these families to receive professional support specifically tailored to their unique health conditions and needs. This study contributes clinically relevant knowledge, and provides insights that can guide the development of targeted and effective support programs based on the family system as a potential resource in grief. Moreover, the the study advocates for a comprehensive initiative aimed at identifying and delivering grief support to these mourners, with a particular emphasis on addressing the unique needs of adolescents in such circumstances.

Acknowledgements

The authors sincerely thank the children, adolescents and parents for their valuable contributions to this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adkins, J. W., Weathers, F. W., McDevitt-Murphy, M., & Daniels, J. B. (2008). Psychometric properties of seven self-report measures of posttraumatic stress disorder in college students with mixed civilian trauma exposure. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 22(8), 1393–1402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2008.02.002

- Andriessen, K., Krysinska, K., Rickwood, D., & Pirkis, J. (2022). Finding a safe space: A qualitative study of what makes help helpful for adolescents bereaved by suicide. Death Studies, 46(10), 2456–2466. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2021.1970049

- Andriessen, K., Draper, B., Dudley, M., & Mitchell, P. (2016). Pre- and post-loss features of adolescent suicide bereavement: A systematic review. Death Studies, 40(4), 229–246. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2015.1128497

- Antonovsky, A. (2001). Unravelling the mystery of health: How people manage stress and stay well. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

- Arnberg, F. K., Michel, P. O., & Johannesson, K. B. (2014). Properties of Swedish posttraumatic stress measures after a disaster. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(4), 402–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.02.005

- Bergman, A.-S., Axberg, U., & Hanson, E. (2017). When a parent dies: A systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers. BMC Palliative Care, 16(1):223. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0223-y

- Boelen, P. A., & O’Connor, M. (2022). Is a sense of coherence associated with prolonged grief, depression, and satisfaction with life after bereavement? A longitudinal study. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 29(5), 1599–1610. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2774

- Cerel, J., & Aldrich, R. S. (2011). The impact of suicide on children and adolescents. In J. R. Jordan & J. L. McIntosh (Eds.), Grief after suicide: Understanding the consequences and caring for the survivors (pp. 81–92). Routledge.

- Cerel, J., Jordan, J. R., & Duberstein, P. R. (2008). The impact of suicide on the family. Crisis, 29(1), 38–44. https://doi.org/10.1027/0227-5910.29.1.38

- Creuzé, C., Lestienne, L., Vieux, M., Chalancon, B., Poulet, E., & Leaune, E. (2022). Lived experiences of suicide bereavement within families: A qualitative study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(20), 13070. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph192013070

- de Groot, M., Neeleman, J., van der Meer, K., & Burger, H. (2010). Family-based cognitive-behavior grief therapy to prevent complicated grief in relatives of suicide victims: The mediating role of suicide ideation. Suicide & Life-Threatening Behavior, 40(5), 425–437. https://doi.org/10.1521/suli.2010.40.5.425

- Del Carpio, L., Paul, S., Paterson, A., & Rasmussen, S. (2021). A systematic review of controlled studies of suicidal and self-harming behaviours in adolescents following bereavement by suicide. PLoS One, 16(7), e0254203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254203

- Delgado, H., Goergen, J., Tyler, J., & Windham, H. (2023). A loss by suicide: The relationship between meaning-making, posttraumatic growth, and complicated grief. Omega, 2023, 302228231193184. https://doi.org/10.1177/00302228231193184

- Epstein, N. B., Baldwin, L. M., & Bishop, D. S. (1983). The McMaster Family Assessment device. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 9(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1983.tb01497.x

- Epstein, N. B., Bishop, D. S., & Levin, S. (1978). The McMaster model of family functioning. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 4(4), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1978.tb00537.x

- Eriksson, M., & Lindström, B. (2005). Validity of Antonovsky’s sense of coherence scale: A systematic review. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 59(6), 460–466. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2003.018085

- Erlangsen, A., Runeson, B., Bolton, J. M., Wilcox, H. C., Forman, J. L., Krogh, J., Shear, M. K., Nordentoft, M., & Conwell, Y. (2017). Association between spousal suicide and mental, physical, and social health outcomes: A longitudinal and nationwide register-based study. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 456–464. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0226

- Falk, M. W., Angelhoff, C., Alvariza, A., Kreicbergs, U., & Sveen, J. (2021). Psychological symptoms in widowed parents with minor children, 2–4 years after the loss of a partner to cancer. Psycho‐Oncology, 30(7), 1112–1119. https://doi.org/10.1002/pon.5658

- Feigelman, W., Gorman, B., & Jordan, J. (2009). Stigmatization and suicide bereavement. Death Studies, 33(7), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481180902979973

- Hjern, A., Arat, A., Rostila, M., Berg, L., & Vinnerljung, B. (2014). Hälsa och sociala livsvillkor hos unga vuxna som förlorat en förälder i dödsfall under barndomen [Health and social living conditions of young adults who lost a parent through lethal causes during childhood]. Report 2014:3. Swedish Family Care Competence Centre (SFCCC), Linnaeus University.

- Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of event scale: A measure of subjective stress. Psychosomatic Medicine, 41(3), 209–218. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004

- Hua, P., Bugeja, L., & Maple, M. (2019). A systematic review on the relationship between childhood exposure to external cause parental death, including suicide, on subsequent suicidal behaviour. Journal of Affective Disorders, 257, 723–734. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.07.082

- Kaspersen, S. L., Kalseth, J., Stene Larsen, K., & Reneflot, A. (2022). Use of health services and support resources by immediate family members bereaved by suicide: A Scoping Review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10016. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610016

- Langius, A., & Björvell, H. (1993). Coping ability and functional status in a Swedish population sample. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 7(1), 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.1993.tb00154.x

- Leung, G. S. M., Lai, J. S. K., Cheung, M. C., Qiaobing, W., & Yuan, R. (2022). Caregivers’ traumatic experiences and children’s psychosocial difficulties: The mediation effect of caregivers’ sense of coherence. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 17(3), 1597–1614. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-021-09966-y

- Margalit, M. (1998). Loneliness and coherence among preschool children with learning disabilities. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 31(2), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940210164920

- Mavranezouli, I., Megnin-Viggars, O., Daly, C., Dias, S., Stockton, S., Meiser-Stedman, R., Trickey, D., & Pilling, S. (2020). Research review: Psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with posttraumatic stress disorder, a network meta-analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 61(1), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13094

- Neimeyer, R. A., Klass, D., & Dennis, M. A. (2014). A social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies, 38(6–10), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187/07481187

- Nilsson, B., Holmgren, L., Stegmayr, B., & Westman, G. (2003). Sense of coherence – Stability over time and relation to health, disease, and psychosocial changes in a general population: A longitudinal study. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 31(4), 297–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/14034940210164920

- Perrin, S., Meiser-Stedman, R., & Smith, P. (2005). The Children’s revised impact of event scale (CRIES): Validity as a screening instrument for PTSD. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 33(4), 487–498. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465805002419

- Pfeffer, C. R., Jiang, H., Kakuma, T., Hwang, J., & Metsch, M. (2002). Group intervention for children bereaved by the suicide of a relative. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(5), 505–513. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200205000-00007

- Roseman, M., Kloda, L. A., & Thombs, B. D. (2016). Accuracy of depression screening tools to detect major depression in children and adolescent: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 61(12), 746–757. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743716651833

- Ross, A. M., Krysinska, K., Rickwood, D., Pirkis, J., & Andriessen, K. (2021). How best to provide help to bereaved adolescents: A Delphi consensus study. BMC Psychiatry, 21(1), 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03591-7

- Räty, L. K. A., Wilde Larsson, B. M., & Söderfeldt, B. A. (2003). Health-related quality of life in youth: A comparison between adolescents and young adults with uncomplicated epilepsy and healthy controls. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 33(4), 252–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00101-0

- Schreiber, J. K., Sands, D. C., & Jordan, J. R. (2017). The perceived experience of children bereaved by parental suicide. Omega, 75(2), 184–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222815612297

- Schäfer, S. K., Becker, N., King, L., Horsch, A., & Michael, T. (2019). The relationship between sense of coherence and posttraumatic stress: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1562839. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2018.1562839

- Silvén Hagström, A. (2021). A narrative evaluation of a grief support camp for families affected by a parent’s suicide. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 783066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.783066

- Silvén Hagström, A. (2019). Why did he choose to die?: A meaning-searching approach to parental suicide bereavement in youth. Death Studies, 43(2), 113–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2018.1457604

- Sveen, J., Low, A., Dyster, A., Ekselius, L., Willebrand, M., & Gerdin, B. (2010). Validation of a Swedish version of the Impact of Event Scale-Revised (IES-R) in patients with burns. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 24(6), 618–622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.03.021

- Telman, M. D., Overbeek, M. M., de Schipper, J. C., Lamers-Winkelman, F., Finkenauer, C., & Schuengel, C. (2016). Family functioning and children’s posttraumatic stress symptoms in a referred sample exposed to interparental violence. Journal of Family Violence, 31(1), 127–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-015-9769-8

- Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The impact of the event scale: Revised. In J. P. Wilson, & T. M. Keane (Eds.). Assessing psychological trauma and PTSD: A practitioner’s handbook (pp. 399–411). Guilford Press.

- Wilson, A., & Marshall, A. (2010). The support needs and experiences of suicidally bereaved families and friends. Death Studies, 34(7), 625–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481181003761567

- Winchester Nadeau, J. (2001). Family construction of meaning. In R. Neimeyer, (Ed.). Meaning reconstruction and the experience of loss (pp. 95–111). American Psychological Association.