Abstract

For most of her career thus far, Taylor Swift’s cultural outputs have remained apolitical, often addressing heteronormative notions of romance, young adult life, and heartbreak. In 2019, Swift broke her politicised silence with ‘You Need to Calm Down’, a track which self-proclaims the artist as an ally to LGBTQ+ communities through her co-option of language historically used to silence marginalised voices, and the inclusion of LGBTQ+-identified celebrities in the accompanying music video. Through a critical technocultural discourse analysis (CTDA) approach, and incorporating digital ethnography, this article examines and compares the multimodal response to ‘You Need to Calm Down’ on TikTok and Twitter. CTDA multimodal analysis is utilised as a method to ascertain both the cultural situatedness of the track, its reception through digital spaces, and also how that reception is connected to the conventions of each platform. Through an analysis of over 20,000 tweets utilising the #YouNeedToCalmDown hashtag, and over 100 TikTok videos based on the track, I examine platform-specific discourse: the de-politicised mimetic creativity of TikTok in comparison to the more hegemonic interpretations found on Twitter. Discussion is organised around three themes of response to ‘You Need to Calm Down’: online communities and ambient affiliations, performative allyship, and cancel culture.

Introduction

In 2019, after a thirteen-year career in which she largely remained apolitical in her public persona, even during accusations of white supremacist affiliations, Taylor Swift pronounced herself as an LGBTQ+ ally with ‘You Need to Calm Down’ (henceforth YNTCD). This release is widely regarded as her first politically-motivated record and music video, and aligns with her newfound voice in social justice public discourse.

The online discourse surrounding Swift’s release and declaration both politicised and depoliticised her intended messages. But with a caveat that by depoliticising the message, it does not necessarily become neutral, but rather political, or representational, in other ways. The reception is situated within a broader platform-specific fracturing of media reception which demonstrates the cultural affordances of platforms that have often been overlooked in social media research. In response, André Brock (Citation2018) calls for an increased ‘critical cultural approach’ to new media technologies through critical technocultural discourse analysis (CTDA), which this article uses as a methodological starting point.

By releasing YNTCD, Swift explores three themes in her work: her allyship towards LGBTQ+ communities and pro-gay rights activism; the silencing attempts from her online trolls; and a critique of the ways in which mainstream media pit women against each other, using her relationship with Katy Perry as an example. How these themes were responded to on Twitter and TikTok varied, reflective of the conventions and affordances of the platforms. While the mainstream press is not examined in detail in this article, much of their criticism and review is based on Twitter response, but, as will be outlined, the politicisation and critique of Swift’s allyship is often taken out of context. In addition, TikTok users engage less with the original themes of the song/music video, but instead rework the YNTCD ethos towards something more universal, familiar, and at times tapping into a longer, and gendered, history of ‘silencing’. Instead of an outright politicisation of Swift’s allyship, TikTok users are seen to be layering culturally and historically embedded meanings over what, at first, appear to be quite mundane experiences.

This article explores audience responses to Taylor Swift’s YNTCD through a mixed-methods approach, drawing primarily from CTDA. It compares the discursive and audiovisual reactions of users on Twitter and TikTok, examining how the platform ecologies inform audience participation. Through this exploration, Swift’s intended meanings surrounding allyship, pro-gay rights, and anti-women on women criticism, are found to be mirrored and amplified on Twitter, while TikTok predominantly reinterprets these themes towards a more general, and often humorous, commentary on silencing within familiar relationships, and ecstatic sociability. CTDA calls for an examination of both the media text, and the media environments, or technologies, on which it is taken up, as well as of how audiences participate in culturally situated discourses surrounding a media text. Brock (Citation2018) notes that, throughout the development of the field of social media research, apps and platforms were studied indiscriminately, centring the discourse over interface. With the field being more established, it is now necessary to look critically at the relationships between platform, culture, and ‘offline’ communities, identities, and practices. Within the YNTCD case study in particular, it could be argued that YNTCD functions as a technology of engagement, mediating not only Swift’s meaning, but also the shared meanings of communities and affiliations.

‘You Need to Calm Down’: Swift Speaks

On June 14th, 2019, Taylor Swift released YNTCD as the second single for her seventh studio album, Lover (2019). On June 17th, 2019, the accompanying music video was released, following a series of video stills shared on her social media accounts. According to media interviews which question Swift on her lyrics and audiovisual design, Swift’s intentions for the song and video were to position herself as an ally to LGBTQ+ communities, while also speaking out about negative online discourse, and the ways in which popular female entertainers are pitted against each other in the press and social media.

The origin story or urtext concerns Swift’s desire to ensure that her stance on social justice issues, and LGBTQ+ rights in particular, was made known to the public, as a ‘coming out’ of her position as an ally. In an interview with Vogue (Aguirre Citation2019), when asked about her positionality, Swift responds:

Maybe a year or two ago, Todrick and I are in the car, and he asked me, What would you do if your son was gay?

…

‘The fact that he had to ask me … shocked me and made me realize that I had not made my position clear enough or loud enough,’ she says. ‘If my son was gay, he’d be gay. I don’t understand the question.’

…

If he was thinking that, I can’t imagine what my fans in the LGBTQ community might be thinking, she goes on. ‘It was kind of devastating to realize that I hadn’t been publicly clear about that.

‘The first verse is about trolls and cancel culture,’ she says. ‘The second verse is about homophobes and the people picketing outside our concerts. The third verse is about successful women being pitted against each other.’

Aesthetically, the YNTCD music video is set in a pastel, colour-blocked trailer park, inhabited by Taylor Swift and various queer or ally-identified celebrities. These celebrities include drag queens dressed in the images of female singers who have ongoing associations with queer communities, evoking simulacra of allyship in this aestheticized trailer park. While the video has faced criticisms of homonormativity (Lewis Citation2019; Bennett Citation2014), it nevertheless does function as a noteworthy text of queer representation. In addition, the video features a group of ‘trailer trash’ protesters, depicted in opposition to the hyper-colourful celebrities. This imagery has been criticised in the mainstream press as a misguided representation of the poor and working class (Hubbs Citation2019; Lewis Citation2019), prompting Swift to clarify that it is intended to be a personification of religious protesters:

Meanwhile, the protesters in the video reference a real-life religious group that pickets outside Swift’s concerts, not the white working class in general, as some have assumed. ‘So many artists have them at their shows, and it’s such a confounding, confusing, infuriating thing to have outside of joyful concerts,’ she tells me. ‘Obviously I don’t want to mention the actual entity, because they would get excited about that. Giving them press is not on my list of priorities’. (Aguirre Citation2019)

Methodologies

Methodologically, this study is grounded in Brock’s (Citation2018) CTDA method, and built on a digital ethnography foundation. The use of CTDA is to respond to Brock’s calls to move away from ‘generalities’ of the internet ‘without unpacking the ideological content of those generalities’ (Brock Citation2018, 1019). In responding to the discourse of Swift’s video, I also respond to the cultural context of where the discourse exists, and the affordances of each platform’s design. Brock lists two requirements for CTDA research: that the theoretical framework should ‘draw directly from the perspectives of the group under examination’ (Brock Citation2018, 1017) and that critical technoculture is incorporated into said framework. CTDA examines culture as technological artefact, and is a:

critical cultural approach to the Internet and new media technologies, one that interrogates their material and semiotic complexities, framed by the extant offline cultural and social practices its users engage in as they use these digital artefacts. (Brock Citation2018, 1013)

CTDA, as a methodology, is quite prescriptive and not yet widely used, but its application could extend to all aspects of internet use, and the communities that come together or form online. For example, Miriam Sweeney and Kelsea Whaley (Citation2019) use CTDA to analyse the technocultural properties of emoji skin tones, connecting the Unicode technical writing to cultural understandings of emojis and skin colour, and how these modifiers continue to centre whiteness. Apryl Williams’ (Citation2017) CTDA work examines fat people of colour on Tumblr, and their counter-narratives to hegemonic depictions of thinness. Catherine Knight-Steele (Citation2018) investigates how Black blogger discourse challenges oppressive systems. And Rachel Kuo (Citation2018) examines the intersections of feminist and racial justice discourse through the Twitter hashtags, #NotYourAsianSideKick, and #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen. Brock, himself, originally used CTDA for research into racialised and marginalised groups, but notes that it can be extended to other ‘ism’ discourses and ideologies (Citation2018; Sweeney and Brock Citation2013).

The current research began with ongoing participant observation of both TikTok and Twitter as sites of public engagement with popular music texts and artists. As the commitment to undertake research on Swift’s YNTCD video reactions emerged, such participant observation became more concerted, adopting a digital ethnographic exploration of audience practices surrounding the video, and, in particular, the differences in reception between the two apps. As Pink (Citation2009) notes, this contextual and embodied engagement with social media is integral to the ethnographic experience, particularly when working across platforms and online/offline communities, in a co-production of knowledge. Postill and Pink (Citation2012) write of the ‘messy fieldwork environment’ of internet research as it intersects with the researcher’s way of knowing. This study is no less messy.

Data collection differed between TikTok and Twitter, owing to the API restrictions of the apps. As Twitter restricts general use of its API to historical tweets within the past seven days, and/or real-time data mining with limitations, Sandbox enterprise API access was acquired, allowing for full-history search utilising a Python script. Historical tweet searching was limited to tweets in English containing the #YouNeedToCalmDown hashtag, which returned 20,448 results. The full dataset was coded in Nvivo through word frequency and text search functions, alongside mind mapping techniques, in order to determine the main themes of the dataset. Rapidminer was then used to generate a proportional sample of 500 tweets, which were coded by hand for sentiment/attitude.

For sentiment coding, I coded tweets as positive if they demonstrate support for the song/video, support for gay rights, and/or a general positive attitude. Tweets are coded as neutral if they contain factual information without bias, and negative tweets are those that are explicitly negative towards the song/video, towards communities/individuals, or just in general attitude. Issues that arise in sentiment coding of tweets is the need to understand the meaning of the tweets, as tied to the language conventions of the platform. As such, it is important to have knowledge of the platform-specific semiotics in order to code sentiment and attitude accurately. For example, ‘I’m dead’ as a form of praise, ‘stan’ as an indication of a high level of fan praise, and sarcasm which can only be understood within the wider context of the user’s tweets, and wider Twitter language conventions.

As there is currently no API that allows for data mining of TikTok videos, the TikTok dataset was collected manually, by searching within the app, and collecting relevant compilation videos on YouTube. Part of the limitation of this research is the lack of ability to download complete datasets of TikTok videos, as well as the influence of geolocation and algorithms on search results built into the app functionality. In total, 109 videos were compiled and manually coded in regard to video themes.

Research Limitations

A number of limitations exist within this research, including researcher decisions, copyright restrictions, and API limitations. By narrowing my focus to only tweets that utilise the #YouNeedToCalmDown hashtag, and TikTok videos that use the YNTCD audio, this eliminates potentially differing results through the exploration of other hashtags, such as #YNTCD, or TikTok videos that reference #YouNeedToCalmDown, but without Swift’s audio. It is generally accepted that hashtags are often used as amplification, community building, and/or digital protest (Gruzd, Wellman, and Takhteyev Citation2011; Zimmerman Citation2017; Tremayne Citation2014), and it is entirely possible that different findings would emerge based on different hashtags/videos. For example, users may not want to align themselves publicly with Swift’s fandom, or may utilise selected hashtags as a way to co-opt, or disrupt, community/fan messages, as noted in Christina Neumayer and Bjarki Valtysson’s (Citation2013) study of neo-Nazi’s on Twitter, whereby the #19februar, #13februar and #RaZ10 hashtags served as a site of conflict between neo-Nazi and antifa groups.

The lack of a complete dataset for TikTok videos necessitates that much of this research becomes a co-creation of knowledge, based on my own searching strategies and results that are often framed by algorithmic predictions. Beyond TikTok’s geolocation restrictions, there is no master feed on TikTok whereby you can view all videos published, in the same way that you cannot view all of Twitter. Twitter user experience is based on who you actively follow, whereas TikTok feeds are organised around your followers, as well as a ‘For You’ page/feed, which is algorithmically produced. For myself, as a late 30s, female, white Canadian emigrant in the United Kingdom, my TikTok experience would no doubt be much different than that of the main demographic of users; I am often shown videos that are hashtagged #Over30TikTok. Demographically, 57% of users are based in China (using the Douyin app), and while demographics were originally skewed towards a quite young user group, more recently it has been found that 60% of US users are between 16 and 24, and over 50% of users in the United States are aged 18–34. Because users under the age of 18 are not included in most published demographics, it is fair to assume that underage users may actually skew the data downwards, if they were to be included (Iqbal Citation2020).

Copyright restrictions also pose a serious limitation to this study, for a number of reasons: TikTok data collection; the ways in which certain audio files are restricted in particular countries; and the dynamic nature of copyright and infringement practices. This study is also a reminder of the ephemeral nature of the internet, where, in some ways, the adage that ‘the internet is forever’ does not always hold true. When YNTCD was originally released, Swift’s version was used as the basis for TikTok videos internationally, but, at some unknown point, the audio was restricted to the United States, limiting the videos I could access from the United Kingdom. Utilising the curated YouTube playlists of TikTok videos imposes an additional layer of taste preferences and value judgements, which is perhaps not a limitation, but reflective of the realistic interactions of subjects and communities within social media research, and demonstrates the fluidity of texts across social media platforms, extending the networks of audience attention and participation.

Whereas remix and reproduction are central to the ethos of TikTok, elements of remix are nevertheless also integrated into Twitter, particularly in the participatory fan and audience practices, in relation to popular media/cultural texts (Jenkins Citation2006). The relationship between copyright ownership, social media, and fan-created works ties into bigger issues in the industry surrounding creativity and intellectual property. For example, TikTok does provide licenced audio for use, but users are not restricted to licenced works when uploading audio. Like YouTube, it is up to the copyright owners to issue warnings and take-down notices.

Findings

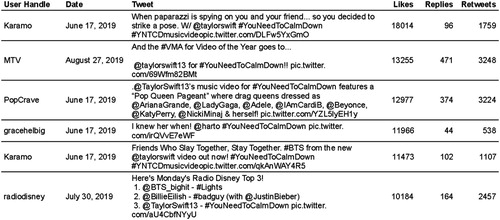

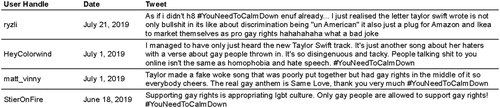

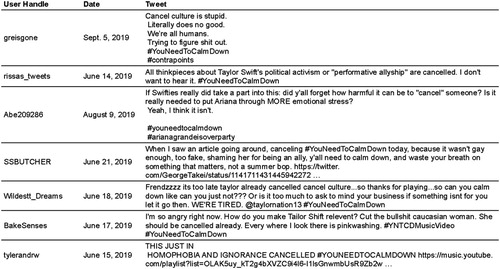

While at first glance it might not seem methodologically appropriate to compare the predominantly text-based outputs of Twitter with the audiovisual format of Tiktok, it should nevertheless be noted that in the 20,448 tweets with the #YouNeedToCalmDown hashtag dated between 13 June 2019 and 13 September 2019, 8.2% (n = 1,675) contain videos, 23.6% (n = 5,855) contain at least one image, and in total, 36% (n = 7,530) contain elements other than text. The most engaged-with tweets, as found in , are those from verified sources, most notably celebrities (such as Karamo and Bobby Berk, who were also featured in the music video), media institutions (such as MTV, RadioDisney), and promotional media (such as PopCrave, and Swift fandom sites). Traditional celebrity presence is less highlighted in TikTok, and much more aligned with ephermeral celebrity, or micro-celebrity cultures (Marwick and boyd Citation2011; Senft Citation2008) that develop from within the app.

Content analysis of the complete Twitter dataset reveals four main themes: ‘gay’ (with subthemes of ‘pride’ and ‘shade’); ‘queens’ and ‘crown’; Katy Perry; and positive listening experiences. Listening practices are not explored in this article, but within this theme, users are generally encouraging others to stream the video/track on various platforms (Spotify, YouTube), and also expressing support in the form of terms such as ‘liking’ and ‘loving’ the song. Within the streaming market economy, it makes sense that people would direct others to stream the track/video, as this is currently a major form of revenue (if not a problematic economic model) for artists. Streams translate into chart status, and further exposure.

Sentiment analysis of the 500-tweet sample demonstrates an overwhelmingly positive response: 48% (n = 240) of the sample are coded as positive in sentiment, with an additional 46% (n = 228) coded as neutral. Only 6.4% (n = 32) of the tweets are coded as negative. It should be noted that this includes all negative tweets, as found in the sample, whether the negativity is directed toward Swift or others. For example, negative sentiment is often directed towards those who criticised Swift for her approach to allyship:

@figureswift: ‘When Taylor said we all got crowns, she means we ALL got crowns. Except those who take this positive song negatively. Shame on y’all. #YouNeedToCalmdown, seriously’ (2019, June 15)

@this_wade: ‘If you’re mad about a genuine ally celebrating pride with her friends and celebrating LGBTQ artists: #YOUNEEDTOCALMDOWN’ (2019, June 17)

@AndrewMaltbie: ‘Trump’s tweets reveal who he does – and does not – see as American – Vox #TrumpIsRacist #clearv #MoronInChief He IS The #only #problem with #OurLand ‘GO HOME You #Racist #SonofaBitch #YouNeedToCalmDown #Stop making the #USA worse & #split #asshole!!!!!http:/www.voc.com/identities/2019/7/15/20695427/donald-trump-tweet-racist-aoc-tlaib-omar-pressley-nationalism … ’ (2019, July 16)

@foxnbacon: ‘I know we’re supposed to be in love with this Taylor Swift video but the song is just lacking. #YouNeedToCalmDown’ (2019, June 18)

@gayvalidation: ‘#YouNeedToCalmDown is just Bad Blood with gay men instead of Victoria Secret models.’ (2019, June 17)

@MrsKingAnge: ‘Wow #YouNeedToCalmDown is such a triggering song. Also, telling someons to calm down only makes the situation worse. #nextsongplease’ (2019, June 14)

This reporting strategy has potentially significant ramifications for how meaning circulates within a society. To disproportionately promote controversy and crisis as public sentiment over, in this case, a quite balanced and positive response to a media text, runs the risk of further dividing cultural and political groups, and amplifying conflict. This is not to say that Twitter is without voices of controversy, crisis, and critique, but that in this specific case study, positive responses are often downplayed in reporting of Twitter sentiment by the mainstream press, indicating that this reporting strategy should be further examined, especially in regard to how news is circulated that might not intend to be ‘fake news’, but actually is. In the words of Kanye West (Citation2020), ‘You know that it’s fake if it’s in the news’.

To connect these findings to the ecology of Twitter, they highlight how voices can be amplified and associated with public sentiment, though they are not necessarily reflective of the majority. Further questions need to be asked about how voices are amplified, especially when this is then connected to wider issues such as Twitter’s cancel culture (Ng Citation2020). Swift, in addressing her online ‘trolls’ in YNTCD, is effectively making a commentary on Twitter’s prevalence towards hive-mind critiques of individuals, which, compounded with the 280-character limit, negates complicated discussions and analytical debate in favour of silencing opinions through a shut-down of discourse, or calls to ‘calm down’. For context, Ng defines cancel culture as:

the withdrawal of any kind of support … for those who are assessed to have said or done something unacceptable or highly problematic, generally from a social justice perspective especially alert to sexism, heterosexism, homophobia, racism, bullying, and related issues. (Ng Citation2020, 623)

With these shifts in demographics, more attention has been paid to ‘drama’ and controversy, and social justice themes have also been increasingly incorporated into video themes. Although YNTCD was released before the largest influx (thus far) of older users, these pre-existing shifts in demographic and content provided a space that was well-positioned to respond to Swift’s video and social justice themes.

Of the 109 TikTok videos utilising Taylor Swift’s originally recorded chorus to YNTCD, the dataset was then reduced to 96 videos, by excluding those that did not utilise the YNTCD challenge. The remaining 96 videos all follow the same format: a set-up where someone (either the user or the user pretending to be someone or something else) is being loud, obnoxious, or excessively expressive in some way; and a response where someone/thing reacts to such behaviour (usually the same user, but playing a different role) by lip synching to the ‘you need to calm down; you’re being too loud’ lines as if they were saying these to the first subject. A typical format is as follows:

Scene 1: (lyrics overlaid on shot of creator acting out youthful exuberance) *Friends screaming/laughing loudly at 4am in my house*

Scene 2: (lyrics overlaid on shot of creator looking annoyed) *Me with strict parents*

Scene 3: (creator lip-synching to lyrics: You need to calm down, you’re being too loud)

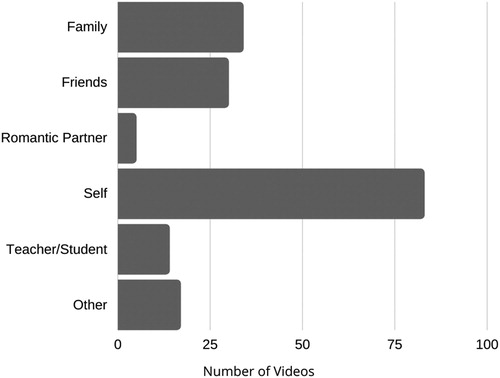

Group dances are popular on TikTok, and dance videos are increasingly a way in which youth measure the meaning of music in their lives (Fogarty Woehrel Citation2021), but the current case study suggests that the #YouNeedToCalmDown challenge is largely an individual one, with the humour of one person playing multiples roles in a conversation being used to downplay the seriousness of the event. The challenge format also provides an easy-to-create video format with the potential to go viral, based not only on the popularity of the challenge, but also on the song itself. Because of the individualism of the challenge, the point of view of the videos is mostly a combination of switching between first-person POV and the POV of the respondent, under the assumption that, in those moments, the viewer takes on the role of the first subject, viewing the scenario through their perspective. In this study’s dataset, POV (where the viewer as viewing subject) is observed in 18% (n = 17) videos, selfie (where the creator filming themselves as their own subjectivity) in 8.3% (n = 8), and mixed (videos that switch between subject creator and other subject positions in their POVs) occupying the majority with 74% (n = 71).

In her study on the management of hysteria by police, Mardi Kidwell finds that in co-present situations, ‘gaze is a central … mechanism for entry into, coordination, and maintenance of face-to-face interaction’ (Kidwell Citation2006, 745). As police officers seek to counteract hysteria, procuring one’s gaze is an imperative step towards directive action. Through the role-playing of imperatives to ‘calm down’ on TikTok, the gaze is offered to the viewer, as they both witness the effects of the controlling gaze, and the results, as they view the ‘hysterical’ subject’s response. This analysis could be further extended into theories of voyeurism and scopophilia (Mulvey Citation1975), which are unfortunately outside the scope of this article.

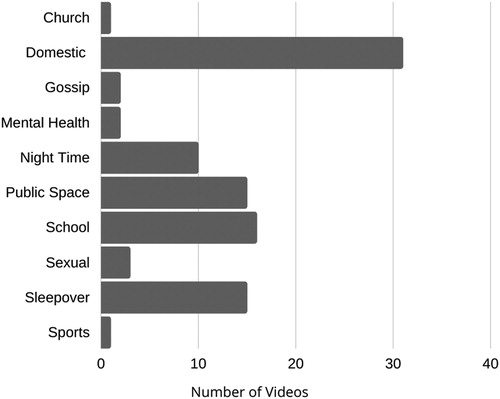

Space and place are identified as important qualities of the TikTok video dataset. The themes of the video demonstrate key features in the relationship between app use, personal relationships, and the spaces in which they occur. Within the narratives of these videos, when considering the implied locations of each video, 63% (n = 66) take place in domestic environments, 17% (n = 18) in public spaces, and 16% (n = 16) in school, presumably high/secondary school. That being said, only one video was actually recorded in a public space, with the remainder being recorded in what appears to be creators’ homes, and, for the most part, bedrooms. The spaces and places are further broken down in to provide more nuance in how space/place connects to the narrative theme.

Given the relatively young age of the users, it is unsurprising that only 3% (n = 3) of videos were of an explicitly sexual nature, and both were providing a POV of one subject looking towards another subject (the creator), and implying that they should be quieter while receiving oral sex. These videos feel largely out of sync with the themes of the remainder, which predominantly centre around people being too loud at sleepovers, where either the user, or the parents of the house they are in, would like them to ‘calm down’.

Due to the young age of the creators, it is also unsurprising that not only are most of these narratives set in domestic spaces or schools, but they are also built around a storyline of the user interacting with either their friends or family—but role playing both parts in the video. As shows, the creator is present as themselves in 86% (n = 83), alongside a role-played version of their friends (30%, n = 31), or family members (35%, n = 34).

Discussion

CTDA calls for a theoretical framework that emerges from the cultural context of the texts being analysed. As both Swift’s video and the response to said video focus on themes of gay rights, female friendship, and online discourse, my findings are nevertheless examined through a feminist and queer theory lens. I also draw on theories of allyship and silencing, in response to Swift’s intended positionality as an ally to LGBTQ+ communities, and the historical context of telling someone to ‘calm down’. This discussion is organised around the three themes of intention and response to YNTCD, reframed as: online communities and ambient affiliations, performative allies, and cancel culture.

Communities & Ambient Affiliations

Investigations of community formation, collective identity, and audience engagement are common frameworks in social media research (Marwick and boyd Citation2011), especially research located in Twitter (Brown et al. Citation2017; Highfield, Harrington, and Bruns Citation2013; Deller Citation2011), and drawing from this, the current study acknowledges that online discourse and engagement are not necessarily removed from offline activities. That being said, owing to the relative newness of TikTok, there is currently no TikTok-specific established framework of analysis. In addition, as outlined above, existing research utilising CTDA and social media platforms tends to incorporate frameworks of counterpublics, imagined communities, subaltern communities, and the like. In this post-social media era, how community and identity exist holistically is cross-platform, but also platform-dependent. Each social media interface affords variances in how a presentation of self and forms of communication can occur, in combination with technocultural conventions that are specific to a platform. Social media are also largely democratic environments, allowing for forms of resistance to dominant/hegemonic conventions, both within the online space and off.

Partially due the nature of the data collection process, the existence of communities in both the tweets and TikTok videos are not well-formed in connection with YNTCD. Associations only loosely exist based on hashtags, song choice, and the structure of the memetic challenge. Regardless of the political nature of Swift’s intended meaning, neither the tweets nor the TikToks demonstrate strong alignment with communities based on counterpublics, the subaltern, and so on. Instead, we see something more akin to ambient affiliation, with individuals temporarily brought together through their reception to the media text, and/or participation in video challenges. It is the experience of such participation that affords affiliation, but not necessarily one that meets the level of ‘community’.

Michelle Zappavigna defines ambient affiliation as a co-present, impermanent community, ‘bonding around evolving topics of interest’ (Citation2011, 800). In her research on #Obama tweets, she outlines how linguistic functions, like the hashtag, bring about these affiliations of discursive communities. This affiliation is seen in the #YouNeedToCalmDown tweets, as the hashtag has both semiotic and social potential, but these affiliations can also be extended into the audiovisual format of TikTok, where we find ambient affiliations based on challenges, and audio choices. TikTok affiliation also occurs in how users allude and recognise communities in their everyday lives, as connected to their domestic, public, and school spaces.

Communities of friendship, family, and peerage, are mediated through the TikTok challenge and its standardised format, allowing young creators to connect with others through their shared experiences of familial relationships. The videos tap into a commonality of experience that youth face in interactions with authority figures (parents, teachers), and also in negotiating one’s position within a peer group. That these videos are being shot and edited largely in one’s bedroom, only further connects these practices to wider accounts of the shifting of bedroom culture online, whereby the process of working through one’s emotions and experiences, through journaling or talking with friends, is relocated online and into the public domain, and thereby subject to public debate and discourse (Avdeeff Citation2021; Hodkinson and Lincoln Citation2008; Bovill and Livingstone Citation2001).

These TikTok affiliations do not appear to show any indication of Swift fandom, or engagement with the three themes of the YNTCD video/song. The song merely exists as a medium for the narrative format, documenting common experiences of being told, or telling another, that they are being ‘too loud’ and ‘need to calm down’. The track functions well within the format of the app, as the chorus fits nicely into the 15 s timeframe, and is deterministic enough to create a narrative that is easy to engage with, and provides enough information for viewers to understand, relate to, and be drawn in with the POV experience.

Performative Allies

In an interview with Vogue magazine (Aguirre Citation2019), Swift outlines her motivation for publicly declaring herself an ally to queer communities:

Rights are being stripped from basically everyone who isn’t a straight white cisgender male. I didn’t realize until recently that I could advocate for a community that I’m not a part of. It’s hard to know how to do that without being so fearful of making a mistake that you just freeze. Because my mistakes are very loud. When I make a mistake, it echoes through the canyons of the world. It’s clickbait, and it’s a part of my life story, and it’s a part of my career arc.

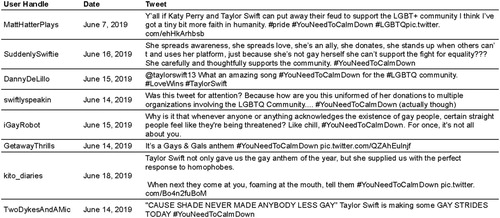

While the press utilise tweets to provide evidence of this discourse of queer baiting and pink washing, the #YouNeedToCalmDown dataset demonstrates a positive response to Swift’s position as ally, regardless of its potential performativity. This performance may be tied to issues of homonormativity in how queerness is represented in the video, but many fans are still happy to see this representation in the media, especially for someone with the level of platform that Swift has, and even more so when compared to how politicised messages have been received and denigrated historically by country music artists, like the Dixie Chicks. Swift has shifted from country to pop music, but nevertheless still retains connections to that cultural space ().

Narratives of queer identities, or notions of being an ally are not evidenced in any of the 109 TikTok videos using the YNTCD audio. That aspect of Swift’s text is entirely negated on TikTok, owing to the way in which audio is reworked on the app. This is not exclusive to Swift’s audio, but is a common feature of the app, where sounds and lyrics are repurposed for new aims, aligned with various ‘challenges’. In addition, users often draw attention to this phenomenon, when challenges are particularly out of sync with the song’s original ‘meaning’.

Just as technologies afford unintended uses, so do audiovisual texts. TikTok draws attention to how users participate in media texts, both responding and producing through innovation and remix. These ‘unintended’ responses are more prevalent on TikTok than they are on Twitter, which increasingly values and centres cultural ownership of texts, and the authenticity of interpretation as connected to identity politics.

You Need to Calm Down & Cancel Culture

Taylor Swift opens YNTCD with:

You are somebody that I don’t know

But you’re taken shots at me like it’s Patrón

And I’m just like, damn, it’s 7 AM

Say it in the street, that’s a knock-out

But you say it in a Tweet, that’s a cop-out

And I’m just like, ‘Hey, are you okay?’

For some listeners, by conflating these experiences, Swift was, herself, participating in a form of cancel culture, trivialising queer marginalisation by centring the online bullying of a highly privileged, straight, cis-gender white woman. It was perceived as negating the importance of being an effective ally, further demonstrating the performativity of her positionality. Intriguingly, the critique seems less about Swift’s position as ally, and more about her conflation of LGBTQ+ marginalisation with her own struggles as a celebrity. Although academic research into allies is often examined through student, not celebrity allies, there are some comparisons that can be made here. Kendrick Brown and Joan Ostrove define allies as ‘dominant group members who work to end prejudice in their personal and professional lives, and relinquish social privileges conferred by their group status through their support of nondominant groups’ (Brown and Ostrove Citation2013, 2211), and by not relinquishing her social privileges, Swift’s allyship is interpreted as performance.

Camille Baker (Citation2004) provides further nuance to our understanding of allies, noting that allies exist along a continuum from ‘potential’ to ‘active’ ally. With YNTCD, Swift moved from a potential ally, one whose views remain anonymous in the public domain and lacking the confidence for public exposure, to an active ally, directly challenging homophobia and heterosexism. Although Baker is speaking of students in her research, her point that ‘potential allies can become more visibly engaged if they are encouraged to speak their minds’ (Baker Citation2004, 66) still holds true in this instance: following the largescale response to YNTCD, Swift has since retreated from overtly political themes in her most recent album, Folklore. This new adult contemporary era marks a personal safe space of unpolitical themes, entirely removed from social activism. Knight-Steele (Citation2018), echoing Stuart Hall (Citation1981), notes that ‘privilege dictates that when those of the dominant group create art and entertainment there is no burden of representation’ (Knight-Steele Citation2018, 118–119), and Swift’s positionality allows her to move in and out of these politics of representation at will. However, this is not meant to diminish the efforts she has made with LGBTQA+ representation within this video, or the wider industry shifts she has instigated within the problematic streaming economy.

Instead of being subject to the cancel culture that Swift sings about in YNTCD for her performative allyship, she finds overwhelming support on Twitter. With the recent escalation of cancel culture on Twitter with the #MeToo movement, culminating in the ‘cancellation’ of non-celebrity individuals to little long-term effect, Ng notes that ‘cancel culture itself is now subject to being cancelled’ (Ng Citation2020, 623). This is reflected in the #YouNeedtoCalmDown dataset, where very few tweets using the term ‘cancel’ are doing so in order to cancel Swift. Alternatively, cancel is used as a way to discuss the mainstream media’s attempts to weaponize Swift fandom towards cancel culture ().

Swift’s Twitter audience responds by cancelling cancel culture. Tweets demonstrate a positive response to Swift’s role in increasing queer representation, and her active allyship, in the cancelling of bigotry. Although there are very few tweets which are engaging in nuanced, critical discourse around allyship and LGBTQ+ activism, what is not being witnessed is a complete shut-down of discussion surrounding these issues. If anything, they represent an exasperation at having to defend Swift, and continually fight against LGBTQ+ marginalisation and homophobia in the public domain.

Neither a 280 character tweet, a one minute TikTok, nor a two minute and 51 s music video, affords the space to have a critically engaged and nuanced conversation about representation and gay rights. However, it is interesting to note that, by telling trolls and anti-LGBTQ+ protesters to ‘calm down’, Swift is perpetuating elements of cancel culture by shutting down possibilities of complex discourse and debate. Her work still becomes representative of the cancel culture now endemic in Twitter, both reflecting her audience and legitimising the cancel culture which they seek to redress. The question then becomes whether the narrative of being too loud and the imperative to ‘calm down’ in the TikTok format is, indeed, shifting the politicised nature of Swift’s text, or whether it is a form of cancel culture-lite, connecting to historical and ongoing practices of silencing, which are often gendered.

Conclusion

The TikTok YNTCD challenge may have ‘silenced’ Swift’s pro-LGBTQ+ message, but not through the delegitimization that can be seen in Twitter’s cancel culture. TikTok, instead, can be seen legitimising a commonality of experience through the YNTCD challenge. This is seen not only in this challenge, but throughout TikTok: a sense that putting one’s subjective experiences on the app serves to validate personal experiences, especially for topics that youth (and even adults) find difficult to speak about in person, out of fear of being different. The online disinhibition effect (Suler Citation2005) encourages such sharing of the personal, and in the TikTok comment sections users express gratitude and support by discovering and validating these commonalities. As youth are figuring out their place in the world, and in their own bodies, some spaces of TikTok have become places of validation, breaking down presumed hegemonic understandings of identity, bodily functions, and relationships.

In one of the few currently published works on TikTok, Juan Carlos Medina Serrano et al. note that, due to the audiovisual nature of the app, and the lack of sharing of pre-existing content as is often done on Twitter, the users inevitably become the content. Therefore, ‘every TikTok user is a performer who externalises personal political opinion via an audiovisual act’ (Citation2020, n.p.), highlighting an interactivity of political communication. The results of the current study reflect this interactivity of engagement, through the popularity of the YNTCD challenge format, and the political communication is seen in the reimagination of Swift’s intended meanings. Twitter response, in comparison, aligns more explicitly with Swift’s meanings, providing a positive response to the media text.

To conclude, this article is as much about methodology as it is about critical engagement with Swift’s music video as media text. It examines the ways in which audience response is often platform-dependent, owing to the conventions and cultures apparent within interfaces and platforms. In doing so, it also lays the groundwork for further research examining how meaning circulates through social media, counter to mainstream press narratives.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Melissa K. Avdeeff

Melissa K. Avdeeff is an Assistant Professor in the School of Media & Performing Arts at Coventry University. As a scholar of all things popular, her research is at the intersections of technology, posthumanism, sociability, and reception. She has published works on Beyoncé and celebrity self-representation on Instagram; Justin Bieber and historiography of YouTubers; iPod culture, taste, and sociability; and the audio uncanny valley in AI popular music.

References

- Abraham, Amelia. 2019. “Why Culture’s ‘Queerbaiting’ Leaves Me Cold.” The Guardian, June 29. https://www.theguardian.com/global/2019/jun/29/why-cultures-queerbaiting-leaves-me-cold-amelia-abraham

- Aguirre, Abby. 2019. “Taylor Swift on Sexism, Scrutiny, and Standing Up for Herself.” Vogue, August 8. https://www.vogue.com/article/taylor-swift-cover-september-2019

- Avdeeff, Melissa. 2021. “‘Girl I’m Tryna Kick It With Ya’: Tracing the Reception of the Embodiment of Girl/Bedroom Culture in ‘7/11’.” In Beyoncé: At Work, On Screen, and Online, edited by Martin Iddon, and Melanie L. Marshall, 226–250. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Baker, Camille. 2004. “The Importance of LGBT Allies.” In Interrupting Heteronormativity: Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Pedagogy in Responsible Teaching at Syracuse University, edited by Kathleen Farrell, Nisha Gupta, and Mary Queen, 65–70. Syracuse, New York, NY: Books 14.

- Bennett, Lucy. 2014. “‘If We Stick Together We Can Do Anything’: Lady Gaga Fandom, Philanthropy and Activism through Social Media.” Celebrity Studies 5 (1-2): 138–152.

- Bovill, Moira, and Sonia M. Livingstone. 2001. Bedroom Culture and the Privatization of Media Use [online]. London: LSE Research Online. http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/archive/00000672

- Brock, André. 2018. “Critical Technocultural Discourse Analysis.” New Media & Society 20 (3): 1012–1030.

- Brown, Kendrick T., and Joan M. Ostrove. 2013. “What Does it Mean to Be an Ally?: The Perception of Allies from the Perspective of People of Color.” Journal of Applied Social Psychology 43: 2211–2222.

- Brown, Melissa, Rashawn Ray, Ed Summers, and Neil Fraistat. 2017. “#SayHerName: A Case Study of Intersectional Social Media Activism.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40 (11): 1831–1846.

- Deller, Ruth. 2011. “Twittering On: Audience Research and Participation Using Twitter.” Participations 8 (1): 216–245.

- Fogarty Woehrel, Mary. 2021. “Unlikely Resemblances: Beyoncé, ‘Single Ladies,’ and Comparative Judgment of Popular Dance.” In Beyoncé: At Work, On Screen, and Online, edited by Martin Iddon, and Melanie L. Marshall, 179–197. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

- Gruzd, Anatoliy, Barry Wellman, and Yuri Takhteyev. 2011. “Imagining Twitter as an Imagined Community.” American Behavioral Scientist 55 (10): 1294–1318.

- Hall, Stuart. 1981. “Notes on Deconstructing the ‘Popular’.” In People’s History and Socialist Theory, edited by Raphael Samuel, 227–240. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Highfield, Tim, Stephen Harrington, and Axel Bruns. 2013. “Twitter as a Technology for Audiencing and Fandom.” Information, Communications, and Society 16 (3): 315–339.

- Hodkinson, Paul, and Sian Lincoln. 2008. “Online Journals as Virtual Bedrooms?: Young People, Identity and Personal Space.” Young 16 (1): 27–46.

- Hubbs, Nadine. 2019. “The Poor-Shaming Vision of Pride in Taylor Swift’s ‘You Need to Calm Down’.” frieze, June 26. https://www.frieze.com/article/poor-shaming-vision-pride-taylor-swifts-you-need-calm-down.

- Iqbal, Mansoor. 2020. “TikTok Revenue and Usage Statistics (2020).” Business of Apps, June 23. https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/.

- Jenkins, Henry. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Kehrberg, Amanda. 2015. “‘I Love You, Please Notice Me’: The Hierarchical Rhetoric of Twitter Fandom.” Celebrity Studies 6 (1): 85–99.

- Kidwell, Mardi. 2006. “‘Calm Down!’: The Role of Gaze in the Interactional Management of Hysteria by the Police.” Discourse Studies 8 (6): 745–770.

- Knight-Steele, Catherine. 2018. “Black Bloggers and their Varied Publics: The Everyday Politics of Black Discourse Online.” Television & New Media 19 (2): 112–127.

- Kuo, Rachel. 2018. “Racial Justice Activist Hashtags: Counterpublics and Discourse Circulation.” New Media & Society 20 (2): 496–514.

- Lewis, Rachel Charlene. 2019. “Do We Need to Calm Down?: A Roundtable about Taylor Swift and Classism in Music Videos.” bitchmedia, July 3. https://www.bitchmedia.org/article/taylor-swift-you-need-to-calm-down-classism

- Marwick, Alice, and danah boyd. 2011. “I Tweet Honestly, I Tweet Passionately: Twitter Users, Context Collapse, and the Imagined Audience.” New Media & Society 13 (1): 114–133.

- Mulvey, Laura. 1975. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” Screen 16 (13): 6–18.

- Neumayer, Christina, and Bjarki Valtysson. 2013. “Tweets Against Nazis?: Twitter, Power, and Networked Publics in Anti-Fascist Protests.” Journal of Media and Communication Research 55: 3–20.

- Ng, Eve. 2020. “No Grand Pronouncements Here … : Reflections on Cancel Culture and Digital Media Participation.” Television & New Media 21 (6): 621–627.

- Pink, Sarah. 2009. Doing Sensory Ethnography. London: Sage.

- Postill, John, and Sarah Pink. 2012. “Social Media Ethnography: The Digital Researcher in a Messy Web.” Media International Australia 123–134.

- Richards, Victoria. 2020. “Yes, We've Joined Our Kids On TikTok. This is Why We Love It.” Huffpost, May 3. https://www.huffingtonpost.co.uk/entry/we-are-family-the-boom-of-parent-child-tiktoks_uk_5eaad2d7c5b6efb0d33cff03

- Ross, Andrew. 2019. “Discursive Delegitimisation in Metaphorical #SecondCivilWarLetters: An Analysis of a Collective Twitter Hashtag Response.” Critical Discourse Studies, doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2019.1661861.

- Senft, Theresa. 2008. Camgirls: Celebrity and Community in the Age of Social Networks. New York, NY: Peter Lang.

- Serrano, Juan Carlos Medina, Orestis Papakyriakopoulos, and Simon Hegelich. 2020. “Dancing to the Partisan Beat: A First Analysis of Political Communication on TikTok.” Association for Computing Machinery, Southampton, UK, July 7–10.

- Suler, John. 2005. “The Online Disinhibition Effect.” Applied Psychoanalytic Studies 2 (2): 184–188.

- Sweeney, Miriam E., and Kelsey Whaley. 2019. “Technically White: Emoji Skin-Tone Modifiers as American Technoculture.” First Monday 24 (7).

- Sweeney, Miriam E., and André Brock. 2013. “Critical Informatics: New Methods and Practices.” 77th ASIS&T Annual Meeting, Seattle, USA, October 31–November 5.

- Tremayne, Mark. 2014. “Anatomy of Protest in the Digital Era: A Network Analysis of Twitter and Occupy Wall Street.” Social Movement Studies 13 (1): 110–126.

- West, Kanye. 2020. “Wash Us in the Blood.” Single. GOOD; Def Jam, 2020, digital. Kanye West, Ronny J., Dr Dre, and Dem Jointz.

- Williams, Apryl. 2017. “Fat People of Color: Emergent Intersectional Discourse Online.” Social Sciences 6 (15): 1–16.

- Zappavigna, Michele. 2011. “Ambient Affiliation: A Linguistic Perspective on Twitter.” New Media & Society 13 (5): 788–806.

- Zheng, Jenny. 2019. “Christine and the Queens on Taylor Swift’s “You Need to Calm Down.” Paper, October 1. https://www.papermag.com/chris-taylor-swift-lgbtq-2640810907.html?rebelltitem=3#rebelltitem3

- Zimmerman, Tegan. 2017. “#Intersectionality: The Fourth Wave Feminist Twitter Community.” Atlantis 38 (1): 54–70.