Abstract

In March 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had spread internationally, resulting in governments shutting down concert halls, theatres, and other performance spaces. In this environment, the livestreamed performance flourished, with many musicians embracing the medium, performing to online audiences from their own homes via a variety of social media platforms. Whereas many major performing arts organisations created livestreams that attempted to emulate existing paradigms of concert films, many experimental musicians found ways of subverting these conventions, creating new works that could only have been created during these lockdowns. This article gives an overview of these experimental approaches, documenting the major types of ‘lockdown music’ observed across the international experimental music scene, and exploring their play with the relationships between sound and vision, and with the perception of online liveness. The article then examines a particular case study co-created by the author and composer Damian Barbeler. All My Time is an interdisciplinary work that draws on many of these games of diegesis and syncresis. The pianist duets with an unseen pianist in another country, household appliances become chamber partners with synthesisers, gin bottles are transformed into complex percussion instruments: image and sound seem incompatible, but the audience cannot tell which is live. By documenting the important body of work created during 2020–2021, the article explores how these online performances have expanded the possibilities of interdisciplinary music and the experience of liveness online, forming a basis for a continuing examination of the long-term legacy of ‘lockdown music’.

The COVID-19 pandemic has had many devastating effects on live music performance across the world. Musicians, including those working in contemporary music, were forced to cancel and postpone performances. However, one positive artistic outcome of the first year of the pandemic was the rapid growth of online performances, with many musicians reaching their audiences through their social media platforms. As a result of these unprecedented circumstances, online livestreaming flourished. Although most of these performances attempted to emulate or document the live concert experience, other works expanded and subverted this medium.

This article explores this new online-specific mode of performance in two main sections. The first will give an overview of the main types of innovation found in works performed between 2020 and 2021. This overview is the first major survey of experimental ‘lockdown music’, and provides an important basis for future studies into this body of work. The second section will introduce and provide an auto-ethnographic analysis of my own work (as co-composer and performer) created for livestreamed performance: All My Time (2020), written in collaboration with Australian composer Damian Barbeler for his online HiberNATION Festival. This performance combined live and pre-recorded elements, embracing, rather than hiding, the domestic setting for the performance.

The wide spectrum of music created for online performance in 2020–2021 has already received a significant degree of scholarly and media attention. Lauren Warnecke (Citation2020, 146) has examined responses by dance institutions and communities in the USA. Remi Chiu (Citation2020, 1) has discussed the role of playlists and balcony singing in Milan, drawing comparisons to musical responses to the Milanese plague of 1576. Examining listening habits, Meredith Ward (Citation2021, 8) discussed the phenomenon of watching and listening to silent public spaces streamed on YouTube. And Keley Onderdijk, Freya Acar, and Edith Van Dyck (Citation2021, 4) surveyed 234 instrumentalists and singers in the Netherlands about their motivations for, and experience of, joint music-making online during 2020. There have also been many news articles about livestreaming classical music in outlets such as Vox (Frank Citation2020), BBC News (Hotson Citation2021), the Guardian (Forde Citation2020), the Financial Times (Hunter-Timley Citation2020), the New York Times (Pareles Citation2020), and many others.

However, the specific aesthetic of contemporary/experimental music livestreams has not yet been discussed in detail (the few exceptions are discussed below). This article will not attempt to capture the huge variety of experimental work that has occurred since the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, but it is intended as a step toward discussing the online experimental music of 2020–2021 as a distinctive body of work, which will hopefully attract much more attention in the coming years. After an overview of some film theory and studies of liveness that are relevant to the innovations of 2020–2021, a number of examples of online performances that I have observed will be discussed, divided into categories according to the approach to liveness, the approach to online technology, and the type of interaction between the musicians. Following this, a discussion of my own performance, All My Time, will allow a closer examination of experiments with online presentation, and the challenges in using the internet as a performance medium. Using this sample of online contemporary/experimental music performance during the pandemic, I will identify the main features of this subgenre, and discuss the possible legacy this work will have.

The Aesthetics of Online Performance

Although at the time of writing, the COVID-19 pandemic continues to affect musicians around the world, some musicians are already discussing whether the ‘lockdown performance’ has distinctive characteristics. Neil Luck was one of the first to capture the strangeness of these livestreams, writing in April 2020:

The compressed proscenium of the screen, presenting the vista of an app’s window, offering a glimpse into the miniature stage of the living room, further compressed through optimised video codecs, tiny bitrates, and pithy character limits squashes us in a mise en abyme of increasingly chambered spaces. (Luck Citation2020)

Luck identifies the compositional use of artefacts of streaming technology as a particularly salient feature of experimental online performances: ‘resolution dropouts, audio-clipping, and latency that define the quality of how we now experience the performance of music by others’. Far from being a completely new approach to the screen, Luck views the aesthetics of lockdown performances as an evolution from experiments in cinema, citing film theorist Michel Chion.

Chion (Citation1994, 22–26) identifies three modes of listening: causal (where the source of the sound is identifiable) coded (where the sound carries information to be decoded, such as language), and reduced (where the sound is divorced from a source). These are all at play in online performances, sometimes unintentionally, and sometimes with many in close succession: crossing the boundaries of on- and offscreen, ambient and non-diegetic sounds (78), and shifting between spatial and subjective ‘points of audition’ (88). Crossing these boundaries isn’t novel; the novelty is in the way they are crossed in this online environment. Points of audition are altered by the placement of the microphone on a phone, the binary of on- and offscreen is broken down when the performer is their own cameraperson, ambient and non-diegetic sounds are affected by deliberate manipulations of the video using DIY editing tools, in addition to the unintentional artefacts of recording in a living room rather than a sound-proofed studio, and the compression of audio and loss of fidelity by streaming platforms. Most fundamentally, the online performances I will discuss below play with subversion of what Chion calls the ‘audio-visual contract’, which is ‘a kind of symbolic contract that the audio-viewer enters into, agreeing to think of sound and image as forming a single entity’ (Citation1994, 16). The most innovative works of the last year played with the limitations of equipment and the medium, employing post-Lynchian filmic effects using an iPhone, or as Caitlin Rowley and Josh Spear of Bastard Assignments have discussed, using the glitching artefacts of livestreams as compositional material:

In the Lockdown Jams, we embrace glitch and celebrate its presence. It seems to create an uncertainty, implying that the Internet or medium is itself alive and listening, and that we are live, too. (Citation2021, 15)

Another important factor that gradually changed over the last year was the attitude toward ‘liveness’ online. Philip Auslander has written about the historical contingency of the word ‘live’. What once connoted physical and temporal co-presence between audience and musician becomes less clear when we speak of ‘live broadcasts’ (where the audience and musician are only temporally co-present) and even less clear for ‘live recordings’, when neither of the initial conditions are met (Auslander Citation2008, 61). What makes these live is the audience’s engagement with liveness, as Auslander explains:

The liveness of listening to or watching the recording is primarily affective: live recordings allow the listener a sense of participating in a specific performance and a vicarious relationship to the audience for that performance not accessible through studio productions. (61)

But again, this liveness is different from the online performances of 2020, which had no audience for listeners to vicariously relate to. Auslander points to Nick Couldry’s solution: finding liveness online in social co-presence (Couldry Citation2004, 356). We can also consider online performances as a type of virtual liveness, as defined by Paul Sanden:

Virtual liveness is a perception of liveness—a perception of performance—that embraces a musical experience’s grounding in the various incursions of electronic sound technologies. It involves an extension of the whole concept of performance to include things … which would seem to conflict with traditional definitions of what performance is—and more importantly is not—while at the same time making room (sometimes through simulation or technological enhancement) for certain elements of those traditional definitions to persist. (Sanden Citation2019, 183)

As I will discuss later, some musicians in 2020–2021 dogmatically understood live performance according to Auslander’s definition of ‘live broadcast’, while many others were closer to Sanden’s virtual liveness, playing with traditional approaches while using digital manipulation of the audio-visual materials in ways that deliberately subvert these traditional definitions.

Many of the more novel types of online performance seen in 2020–2021 predate the pandemic by several years. Jason Stanyek and Sumanth Gopinath point to the Starmaker YouTube channel (launched in 2014, starting as an app in 2010), where teenage singers can publish homemade videos as a method of broadcasting musical selfies.Footnote1 The performances by many contemporary/experimental musicians in lockdown were not so far removed from these videos, broadcasting to the public from living rooms and bedrooms (Gopinath and Stanyek Citation2019, 104). Assembled multitrack ‘ensemble’ videos by orchestras, choirs and other large institutions also have pre-pandemic precedents in projects such as Eric Whitacre’s ‘Virtual Choir’, which assembles thousands of user-generated videos and dates back to his Lux Aurumque (2009). I have previously written about my collaboration with Alexander Schubert on WIKI-PIANO.NET (2018), a work open to editing and constant re-creation by the Internet public, itself influenced by the Reddit-based crowdsourced artwork, Place (2017) (Kanga Citation2020, 6).Footnote2 As with experimental video techniques, crowdsourced creativity had been explored and tested before the pandemic, but it found new life and relevance in the lockdown environment.

The dissemination of these works in online spaces allows us to view these works as memetic. A number of other authors in this Special Issue discuss the work of Limor Shifman, whose theory on memes is already highly influential, and relevant to many types of social media-based music (Besada Citation2022; Freitas Citation2022; Viñuela Citation2022). Of particular relevance here is Shifman’s observation that memes facilitate the collision of different types of cultural production, from amateur to experimental to market-driven creations:

Since memes serve as the building blocks of complex cultures, we need to focus not only on the texts but also on the cultural practices surrounding them. Jean Burgess suggests treating YouTube videos as mediating ideas that are practiced within social networks, shaped by cultural norms and expectations … . These examples of historical roots highlight the ways in which practices of re-creating videos and images blur the lines between private and public, professional and amateur, market and non-market driven activities. Thus, Internet memes can be seen as sites in which historical modes of cultural production meet the new affordances of Web 2.0. (Shifman Citation2014, 34)

Not all online performances are memetic, but all of them need to find creative ways to engage with their wider musical culture, and the more specific culture of online performance. In March 2020, historical modes of cultural production and the new affordances of Web 2.0 collided under extreme circumstances, and the examples that follow are among the most interesting results of this collision.

An Overview of Online Performance in 2020–2021

Musicians across every genre participated in the creation of online livestreams and videos during the lockdowns of 2020–2021. Classical music made up an unusually high proportion, relative to the size of the market: according to an industry report surveying 1,484 UK-based musicians about livestreaming, classical music accounted for 29% of all new content, and 27% of online concerts attended. This is higher than the 18% proportion of classical music within all live performance attendances in the UK (over the decade up to 2015) (Arts Council England Citation2015, 15–17). Significantly, 71% of musicians and 68% of attendees believed that online streaming will continue to be a significant part of the music industry landscape into the future (Haferkorn, et al. Citation2020, 46).

There are many possible explanations for this overrepresentation, among them the importance of liveness to classical music, the highly developed infrastructures and platforms of classical organisations, or simply skewed survey data (Haferkorn, et al. Citation2020, 6–7). But it does suggest a high participation rate among classical musicians, and contemporary/experimental musicians, as they were very active creators of livestreams and other online content during this period despite being a small fraction of the larger music industry.

In this section, I attempt to give an overview of the approaches to online performance by contemporary/experimental musicians (taking relatively wide definitions of these genres). This list is naturally skewed towards my own British/Australian contemporary music networks and is not intended to be exhaustive, or to indicate artistic success. Rather, it emphasises the wide variety of approaches to online performance, distributed as livestreamed performances, mixtures of live and pre-recorded elements, and pre-recorded and edited videos. As contemporary music encompasses a huge variety of aesthetic and technical approaches, the number and variety of performances were vastly more than can be categorised in a single study. But I have attempted to include examples of all the major types of performance I observed.

Professionally Edited Concert Films

There were many concert films of performances by major institutions presented online during 2020–2021. In many cases, these were filmed for live audiences in previous years, such as the series of online broadcasts by the Metropolitan Opera.Footnote3 But there were also many professionally filmed and edited performances of newly commissioned work. Although these largely used conventional concert film techniques, they also provided a forum for reaching relatively large audiences, and they created high-production-value documentation for new contemporary orchestral, solo and chamber music in a time when live audiences could not be present.

Some festivals filmed their work for online audiences with large professional crews. The BBC Proms used extensive television crews to film their 2020 performances for online viewing, and even contemporary music festivals such as Tectonics were able to employ professional crews (in this case, through their association with BBCSSO). This professional concert film approach was used by Riot Ensemble for a series of commissions in collaboration with the online gallery Zeitgeist.Footnote4 Featuring many of the UK’s leading composers, portions of the series were also presented at Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, as part of an online-only festival event.Footnote5

These filmed performances allowed new works to reach audiences despite the lockdowns. However, they were not dissimilar to concert films that existed before the pandemic and that will exist far beyond it. Indeed, they provide a model for simultaneous viewing by live and online audiences which has been adopted long-term by venues/festivals such as Wigmore Hall and the 2021 BBC Proms (Royal Albert Hall). Although this method is obviously beneficial to contemporary music, other musicians and presenters explored modes of presentation that only emerged as a result of the pandemic, and which may not survive it.

Assembled Ensemble Performances

One of the most common approaches to ‘lockdown performances’ was the assembling of videos sent in by members of an ensemble or choir. This approach was particularly popular with vocal ensembles and choirs, including The Kings Singers, Rotterdam Philharmonic Orchestra, Orchestre National de Lyon, Opera North, La Scala Philharmonic Orchestra, Milwaukee Symphony Orchestra, Sinfonia Lahti, Baltimore Symphony Orchestra, and the Royal Opera House and Chorus, to name just a selection, alongside many amateur choirs and ensembles (Tilden Citation2020). However, most of these ensembles performed canonical repertoire, with very few new works composed for this format. Few contemporary music ensembles took this approach, preferring to record as groups in the same space, with the small numbers allowing for distanced recording sessions which would be impossible for large orchestras and choirs, except in very large venues. Assembled ensemble performances were also conservative in approach, with the priority being presenting the members of the orchestra/choir to the public (to inspire their audiences and also ask for support) and mimicking music documentary or concert film approaches to editing, rather than attempting to create a new approach to online performance.

However, there were newly commissioned works for this format, which also explored new approaches to presentation. O Cocoon (2020), for distanced ensemble, electronics and video by James O’Callaghan for the Toronto-based New Music Concerts musicians, is a particularly striking example, with ensemble members’ home films of their parts warped, looped and manipulated both sonically and visually to create a video that functions as both an illustration of the audio and as an additional contrapuntal layer.Footnote6

Radio Works

Like livestreaming, the medium of radio facilitated the creation of works that would not be possible in a live setting. One of the most inventive and constantly surprising of these radio works was an extended broadcast featuring Jennifer Walshe and Neil Luck. Anthem Study (2021) was created in a one-day studio session for the New Music Show on BBC Radio 3, and combined improvisation with collage-style editing to create a complex, long-form, interdisciplinary work. The ‘radio work’ format is many decades old: although well-suited to pandemic conditions, it long precedes this period, and will long outlast it.

Lockdown Recordings

A number of composers and performers used the lockdowns as an opportunity to explore and record their solo practice. Café OTO was particularly active in releasing dozens of these recordings over 2020–2021 by a huge range of experimental musicians including Lucy Railton, Tim Parkinson, James Rushford, Rie Nakajima, and Aisha Orazbayeva, founding the TokuRoku label to distribute them. A prime example was Juliet Fraser’s release My Adventures with the TC Helicon Voicelive 3 (2020). She writes on the website of Café OTO,

Fast-forward to March 2020: I decided to take the plunge, to order my own and make this reunion a lockdown project that might save morale and sanity. What’s documented here are my little experiments, recorded over a 6-week period as I got to know the beast, fiddling around with the several hundred preset vocal effects, the manifold possibilities of individual effects (such as harmony and hardtune) and the loop function. Each track was made very fast, with no time for critical reflection.Footnote7

Fraser’s work on this album is exploratory, improvisational and intimate in a way that exemplifies the approach many musicians took to these recordings – it contrasts with the work she often performs as a live musician with ensembles, allowing her to develop this other side of her artistry.

Networked Live Performances

In contrast to the recordings, there were networked live performances where ensembles performed together via livestream, creating internet-based chamber music. There were weekly networked performances by Australian musicians as part of HiberNATION Festival (of which All My Time was a part). These ranged from electronic duos to full ensembles, including a performance I participated in by Ensemble Offspring featuring the live ‘unboxing’ of text scores and performance materials by selected composers, which the ensemble members then performed simultaneously.Footnote8

A more extreme networked performance from Australia was 84 pianos, created by Clocked Out (percussionist Vanessa Tomlinson and pianist/composer Erik Griswold), sound artist Leah Barclay, and video artist Greg Harm. A score by Griswold, originally written as a live work for all the pianos in the Brisbane Conservatorium, with the doors of all the rooms wide open, was sent to 84 pianists worldwide, who performed the work simultaneously. This was achieved by the use of a phone-based app, streaming the audio to Barclay and Harm who mixed these streams together and used them to create live visuals to accompany the performance. Although not all pianists’ streaming connections lasted through the work, and streaming through phones resulted in variable sound quality, the work was impressive for its ambition and the size of the networked ensemble, with more than 100 pianists in the performance (Tomlinson Citation2020).

Composer-performer collective Bastard Assignments extended this approach by commissioning works that featured musical and theatrical interaction, and played with video manipulations of their livestreams, creating ensemble works that were bespoke for the online medium. Of the 12 ‘lockdown jams’ they commissioned,Footnote9 the most arresting were Alexander Schubert’s Browsing, Idling, Investigating, Dreaming—performed on 17 June 2020—which required each of the four ensemble members to generate sounds and visuals from common internet sites (such as Google Maps and Spotify), Michael Brailey’s THISPERSONDOESNOTEXIST—performed on 29 April 2021—which used AI to create grotesque manipulations of each of the ensemble members’ video feeds, and Jennifer Walshe’s zusammen iii—performed on 7 December 2020—which featured the four musicians performing as different types of social media influencers (see ).

Bespoke Online Translations of Live Performance

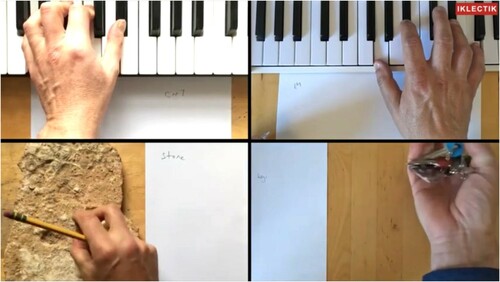

A number of performances used online platforms not just to present, but to translate live performance works into a format that is tailored to this medium. One particularly well-crafted example was No Concert (2021), an online performance by Parkinson Saunders (a duo consisting of Tim Parkinson and James Saunders) presented online by the London venue IKLEKTIK, on 28 May 2021.Footnote10 When playing to a live audience, the duo usually sit at adjacent tables, performing works for a variety of instruments and household materials. In this performance, they combined pre-recorded and live interactions, with closeups of their hands writing graphic and conventional notation, or playing a keyboard and guitar. The effect was a magnified perspective on their live performance practice (see ).

Home-Based Recordings and Livestreams

Many solo performers also took the initiative to create and commission new works for performance from their homes. New York-based pianist Vicky Chow’s commissioning of Michael Gordon to compose JULY (2020) is a prime case: the work features 31 movements, each to be played on the corresponding day in July. Featuring a huge variety of post-minimalist textures, the work showcases Chow’s virtuosity, and could function just as well as a concert work. Like many solo performances, these were single-camera recordings; intimate, direct, and DIY. The performances were streamed on Instagram and Facebook by Chow.Footnote11 In July 2021, Chow invited an international range of pianists (including myself) to play different movements of the work, in videos which revealed the development of the home-performance aesthetic, with much more creative editing, lighting, and play of angles, without any pretence of the performance being live.

Another example (including solos and duos) can be found in the improvisation concert by musicians Andrea Pensado, James L Malone, and Yoni Silver (with visual editing by Tracy Lisk) presented by IKLEKTIK.Footnote12 This series of live improvisations came close to recreating the live interactivity of musicians in the same space, but it also capitalised on online presentation, with the live-stream switching between cameras to show the musicians in their living spaces as well as closeups of their instruments, creating an intimacy to the visual presentation that matched the music. In one such moment in Silver’s solo improvisation, the video feed splits into four, showing different livestream perspectives of Silver playing the bass clarinet while lying on his couch (a wide shot and closeups on the instrument), while the fourth shows a second couch—empty until Silver enters with a violin. The play of perspectives and the reframing of his 3D space for a 2D video presentation creates a contrapuntal presentation of the single instrument performance.

Another common approach by musicians was recording short performances and posting them to social media (rather than using the platforms’ live-streaming options). This allowed for some editing and multiple takes, while remaining spontaneous with a homemade, DIY aesthetic. One of the most acclaimed series of works of this type was Coronasolfege (2020–) by soprano Héloïse Werner.Footnote13 Utilising just her voice and body percussion (mostly on her face), she created 37 short video works. The series was featured on BBC World Service, BBC Radio 3, France Musique, Soho Radio, the Guardian, Classical Music Magazine, and Gramophone Magazine, and has started to generate musicological interest, with Werner discussing the work in a panel session at ‘The Art Song Platform – Art Song out of the Concert Hall’ conference in November 2020. The project received a commendation for the Inspiration Award in the Royal Philharmonic Society Awards 2020, and led to further commissions in the same style for CoMA and the Gesualdo Six. In this case, the success was not a product of digital wizardry, but of a display of very fine compositional and vocal craft in short packages that were ideal for attracting Twitter users’ attention.

There were also public platforms and presentations for homemade videos, with TUSK Festival presenting 76 homemade videos of performers, composers, and improvisors, and Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival featuring homemade performance films (which were, in many cases, filmed and edited at a near-professional standard).

Expanding on the possibilities for solo performance, a number of works edited multiple solo videos together to turn a single performer into an ensemble. Stephen Crowe’s Garfield featured the composer on saxophone and clarinet on 20 April 2021, filmed multiple times in the same location, with the different videos overlayed or intercut in unusual shapes or split-screen to create a solo duet with constantly shifting and surprising visual approaches (see ).Footnote14

Noises with Nina (2020–2021), a series of short video works composed by Nina Whiteman, expanded the home-recorded solo-ensemble concept with contrasting results. Using a variety of small synthesisers, DIY electronic instruments, and other small instruments such as a recorder and household items, she performed on videos around a screen creating increasingly complex textures. The videos are both intimate, using Whiteman’s distinctive direct-to-camera presentation style, as well as experimental in their techniques, with the videos expanding and rearranged across the screen as each new instrumental part is added.Footnote15

There were a few cases of single composers writing a series of works for musicians to record and film at home. Matthew Shlomowitz created a series of works, Music for Cohabitors (2020–2021), written for households of musicians. The series featured chamber ensembles of housemates and families (including young children) with works tailored to the unusual combinations and wide differences in ability.Footnote16 The series now numbers 56 works, including Vaudeville Ternary, featuring two professional musicians and their three sons, Minimal lockdown days, featuring a percussionist and her two daughters, Hexatonic cycle with calm Stanley, featuring a challenge laid out by the composer to his toddler godson, and Hocket drill, Rocket drill, a virtuosic hocketing work played by bass trombonist and bassoonist brothers. Despite the huge variety of performers and abilities, the works are remarkable for their compositional craftsmanship and wit.

Live Demonstration and Commentary

There were also a number of livestreams that had some similarities to performances, but were closer to live documentaries, featuring non-musical content and live commentary from the artist, in the style of video gaming livestreams. Andrew C Smith used Twitch (a platform commonly used by gamers) to livestream himself simultaneously composing on Ableton Live, writing his dissertation, live video chatting with a colleague and playing the game Age of Empires II.Footnote17 In contrast to the other performances listed, there is no attempt to present the video as a performance, or to define a beginning and end – it resembles a live feed into the composer’s computer rather than a deliberate broadcast. And yet the combination of the different musical, academic, video chat, and video-game elements is performative, a broadcasting of multi-tasking virtuosity, and the use of split screen to show the audience the multiple elements simultaneously is a type of compositional choice.

A similar videogame playthrough style was used by Sam Rolfes in his VR and live CGI in livestreams. Using digital puppetry, Rolfes created live online VR performances, swimming and narrating a fish-like avatar through surreal landscapes (created for prior music videos for pop performers). These functioned as behind-the-scenes tours of these VR music videos, while also being performances in themselves.Footnote18

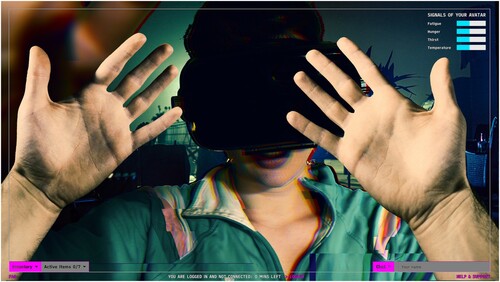

Audience Participation

Particularly ambitious were the lockdown performances that involved audience participation. One of the most groundbreaking projects was Genesis (2020) by Alexander Schubert, which he called a ‘live computer-game’.Footnote19 Users could book a slot to log onto a website, where they were then presented with the perspective of a performer in a room whom they could instruct to perform using a selection of tools (including percussion instruments). The performers wore VR headsets with cameras, allowing them to see the augmented reality perspective presented to online viewers (see and ). This was a rare work that facilitated live online interaction with live performers, creating a new type of participatory composition that transcended the ‘lockdown’ genre.

Figure 4. A performer viewpoint in Genesis by Alexander Schubert. © Alexander Schubert. Used with permission.

Figure 5. Photograph of the performers of Genesis by Alexander Schubert. © Gerhard Kuene. Used with permission.

Holly Herndon’s Holly+ (2020–) emerged out of the lockdown to become a longer-term online project. At the time of writing, Herndon is still inviting participants to submit recordingsFootnote20 that are merged with her voice through machine-learning tools, resulting in strikingly otherwordly sounds that the participating artists can use in their own works. Herndon’s project also facilitates the sale of the resulting works, with a large portion of the profits distributed back to the online participants, and a portion used to further develop the software tools, demonstrating a mutually beneficial model for online participation in new works.

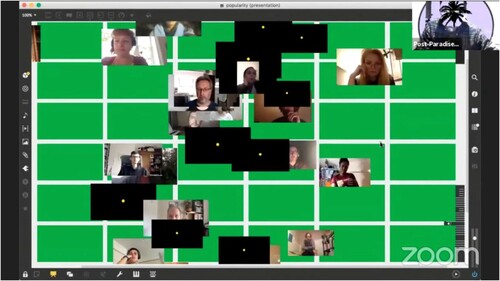

Maya Verlaak’s Popularity, hosted by the Post-Paradise Concert Series on 19 December 2020, had a small audience positioned on screen, similar to a Zoom call. Using a Max patch, Verlaak allowed audience members to appear and disappear by clapping, to change their size on the screen when singing, and to move their screens using blowing sounds (see ).Footnote21 These interactions are not dissimilar to common group improvisation exercises carried out in person (where sound is matched to movement), but translating this to a live online setting made for a particularly impressive audience participation work.

* * *

This huge variety and volume of activity is just a tiny fraction of the work of an entire industry that could not engage in live performance because of the COVID-19 pandemic. All of these examples work with the idiosyncrasies and limitations of online platforms, discovering new ways of using social media that could remain an important part of composition in the future. Before discussing the bigger trends across these many examples, I will discuss my own contribution to the genre, All My Time, a work that pushes the limitations of the medium.

All My Time: A Case Study in Online Performance

On 28 June 2020, I performed a new work co-created with composer Damian Barbeler, All My Time, for the online HiberNATION Festival. This Australian-based festival ran from April–July 2020, during the strictest period of global lockdowns. The work was intended as a collection of movements, each exploring a different approach to online performance. It was originally streamed via the festival website and is now available to view on YouTube.Footnote22 In this analysis, I will discuss the many games that this piece plays with audio-visual interaction and the ambiguity of virtual liveness.

The Performer’s Perspective as Extreme Liveness

As with many of the examples above, All My Time experiments with perspectives that move beyond those of a traditional performance film. When filming a pianist, the standard perspective is a wide shot from the audience’s position, with selected closeups of hands and face. By contrast, All My Time attempts to view the performance from the pianist’s eyes.

The opening movements of the work all use a straightforward notated score. The music is meandering, almost improvisatory in nature within an extended tonal framework. These sections would be engaging but conventional if filmed from the traditional wide angle, but we instead chose an unorthodox and intensely intimate angle, streaming them live from a GoPro attached to a head strap (see ). The audience sees me looking at the keyboard, but in contrast to aerial shots in professional concert films, the effect is jumpy and seemingly chaotic, with an overload of information and movement as the audience experiences the sensory multi-tasking of the pianist. This pianist’s-eye-view feels further exaggerated in a movement using a graphical video score: the viewer watches my translation of painted swirls and flashing dots in real time, with the frantic alternation between score and keyboard creating a disorientation that matches the unpredictable score. A further, subtle disorientation is present through a mismatch between audio and visual perspectives: whereas the visuals present the perspective of the performer, the audio perspective is from microphones placed to the side of the instrument, which is a more traditional audio perspective, emulating the sound of the piano as heard by an audience member sitting in the front row. This is a prime example of Chion’s play of spatial and subjective audition, where there is a mismatch (though very subtle) between how the audience expects the piano to sound from the visual perspective, and the sound they actually hear (Chion Citation1994, 88). In later movements, filmed from a more traditional wide shot, the head-mounted GoPro is removed, creating the illusion that the earlier shots were streamed from the pianist’s own eyes.

This forced perspective, without the relief of wider cuts, makes this technique particular to the livestream genre. Whereas in a concert film, such a perspective would be either fixed, or on Steadicam, and used for quick closeups, the unchanging, unsteady closeup of the pianist’s-eye-view is disorienting and claustrophobic for an audience accustomed to conventional concert films. The perspective also demonstrates an extreme case of Auslander’s model of liveness: rather than facilitating a vicarious relationship to an audience, the viewer experiences the live performance in a vicarious relationship with the performer themselves.

Integration of the Domestic Setting

Like many of the livestreamed performances during lockdown, All My Time does not hide the domestic setting of the performance. Establishing shots from outside my house place the piano room in context (especially the opening single-shot from the street, into the house, and to the pianist’s perspective of the piano’s keyboard). The work also uses domestic appliances as accompaniments to the two synthesiser movements. The first of these pairs a Korg Minilogue with a microwave, whose drone forms a pedal note framing the frantic arpeggios of the synthesiser in a higher register (see ), while the second pairs a boiling kettle with a chorale of gradually swelling horn-like sounds from the Korg. In both cases, the appliance’s ‘finish’ (the water boiling, or the microwave beeping) forces the end of the work—the structure is determined by these domestic goods rather than the musician.

Figure 8. Duet between a Korg Minilogue and a microwave, from All My Time by Zubin Kanga and Damian Barbeler (27'01").

All these scenes help to magnify the claustrophobia of the domestic setting. Further shots away from the piano of wandering around the corridors and staircases of the house further accentuate the ‘lockdown’ experience of confinement. Far from turning it into a substitute concert hall, the house’s architecture and over-familiar contents are amplified.

Syncretic Play with Gin Bottles

A contrast to the piano movements is a short piece playing a set of gin bottles with spoons. Starting with two, bottles are gradually added to the ‘instrument’ creating a range of pitches and timbres, as well as being a humorous commentary on lockdown drinking habits (see ). But the scene is rendered uncanny through a subversion of Chion’s audio-visual contract. Although clearly in another small room in the house, the sound of the bottles resonates as though in a cathedral (using a reverb effect in Logic). The synchronisation of audio and video makes the viewer join the two as a type of ‘syncresis’, which Chion (Citation1994, 62) explains occurs ‘independently of any rational logic’. This audio manipulation makes the familiar strange, in a manner reminiscent of Viktor Shklovsky’s aesthetic theories:

[T]he technique of art is to make objects ‘unfamiliar’, to make forms difficult, to increase the difficulty and length of perception because the process of perception is an aesthetic end in itself and must be prolonged. Art is a way of experiencing the artfulness of an object: the object is not important (Shklovsky Citation1917, 2)

As an inverse to the synthesiser movements where the music is constrained by domestic sounds, this movement explodes domestic sounds in a way that liberates the viewer (and the musician) from the location. It also creates doubt in the listener about the ‘liveness’ of the performance, which is played with further in other movements.

Solo-Ensemble Performance vs Networked Performance

There are a couple of subtle nods to the genre of solo-ensemble performances (such as those of Whiteman and Crowe), including a scene where I stand in my hallway, before being joined by a second, overlayed, video of myself walking down the hall and standing on the opposite wall. In this case, the effect exaggerates the silence of the scene and the sense of waiting for the opportunity to perform live, an experience shared by many other musicians during the first period of lockdown.

As with many of the above examples, networked chamber performance allows another musician to enter what seems like a solo space. In this case, Barbeler was watching and listening to my livestream in London and improvising on his piano in Sydney, with his performance being played on a small speaker inside my piano. Filmed from the traditional wide shot, at first the audience experiences another subversion of liveness, with piano sounds emerging from the instrument when my fingers are not moving. Soon they can perceive a live duet between the live pianist and a hidden partner—the chamber setting is discovered rather than presented. This progression allowed us to play across all of Chion’s sonic zones, from non-diegetic to diegetic (as the audience realises the sound is coming from inside the piano, and interacting live with my performance rather than being pre-recorded) and from off-screen to on-screen.

Divergence of Sound and Video and the Subversion of Liveness

Several of the previous movements manipulated the audience’s perception of the liveness of the performance, but the final movement goes a step further in subverting this expectation. The camera is for the first time focused on my face as a wild, furious, piano-spanning improvisation erupts (see ). But when I bring both my hands to my face as the music continues unabated, the audience perceives a disconnect between audio and visual, without knowing which is live (in this case, it was the audio, but this could have been switched). From the extreme liveness and collapsing of subjectivity of the opening, we here find the opposite, where the audience’s subjectivity becomes the focus—the live visuals of the performance are hidden, but the audience takes some time to realise this—leaving them without any trust in the experience of liveness (under any of Auslander’s definitions). In another context, such breaking of performer-audience trust could be seen as self-defeating, but in the context of lockdown livestreams of 2020, the result is a playful subversion of just-established tropes.

Figure 10 Staring into the camera during the violent improvised final movement, from All My Time by Zubin Kanga and Damian Barbeler (35′45″).

All My Time experimented with audio-visual techniques, and with the nature of online liveness, in ways that would not be achievable to the same extent in a live performance. However, it is also a work of its time, revealing the aesthetic obsessions and allowances of 2020—looking back from 2021, the work’s looseness, the jerkiness of the headset camera positions, and the obsession with the domestic setting date the work in a way that more conventional performance films do not. But perhaps this is also what makes All My Time and the more idiosyncratic online performances of 2020–2021 so fascinating—they have a distinct aesthetic, shared by musicians internationally, a convergence that may not occur again in the near future (or at least until the next global calamity).

Characteristics of the Pandemic-Era Performance

I have identified several salient features that can be observed across online performances of 2020–2021. Some of these features have since become part of the vocabulary for online concert documentation and livestreaming, while others have fallen out of use: experiments in online presentation that have been discarded or superseded.

Breakdown of Public/Private Divide

Social media breaks down the barriers between audience and musicians that were a feature of traditional media, and online performances can be seen as just another method by musicians to bypass traditional gatekeepers to reach their audiences directly. This breakdown of traditional barriers is not necessarily beneficial to musicians—their private spaces are made public, and audiences become accustomed to this type of intimate access. Although some artists relish the opportunity to perform all aspects of their lives, many musicians require privacy, introspection and a safe space for experimentation to create and innovate, as well as to rest and recuperate from the stresses of public performance. The contraction of this private space may seem to have little cost on the surface, but this conceals a bargain that many musicians made in 2020, trading the sanctity of their private practice for continued exposure and income.

Democratisation Through Common Platforms

Online performances also allowed musicians to bypass traditional avenues to performance by using platforms that are as equally accessible to freelance musicians as they are to institutions. Indeed, where some larger institutions struggled to create new content for online performances, focusing on assembled ensemble videos, soloists and small ensembles could be nimbler in finding lateral solutions, whether through networked performances, assembling recordings or commissioning works especially for the platform. This contrasts with the ability of institutions to access larger and more prestigious concert spaces, in comparison to freelancing soloists and ensembles.

Online Performance and Internet Culture

Many of the online performances by freelance musicians noted above can be viewed through the perspective of internet culture. Many of the musical games, translations and playful incongruity of these performances use strategies similar to memes to communicate within the musicians’ communities. Limor Shifman’s model is relevant here: ‘as public discourse, meme genres play an important role in the construction of group identity and social boundaries’ (Citation2014, 100). Just as memes gain currency through communicating to ‘insider’ audiences, we can see these online performances as successful in engaging their specific communities, even though they cannot compete with live performance for live public engagement. Shifman also discusses the use of humour and whimsy to engage insider communities, and a number of works (most notably Matthew Shlomowitz’s series of works, and Neil Luck and Jennifer Walshe’s Anthem Study) featured musical and theatrical humour that engaged with the specialised knowledge of contemporary music audiences.

The Limits of Online ‘Liveness’

Many of the works played with the ambiguity of online liveness through a blending of livestreaming, pre-recorded and edited videos, and recording ‘as-live’ with minimal editing. Although in some cases, this ambiguity was fruitful ground for experimentation and games of deception with the audience, in others it revealed the limits of performing liveness online, where audiences are naturally sceptical about what they view, in comparison to live performance. By 2021, this experimental attitude had disappeared, and a more polished approach to streaming performance has re-emerged on a much wider scale since before the pandemic, either employing television paradigms for filming live performance, or editing videos to ensure the quality of the results. Wigmore Hall’s current livestreaming of their live concerts exemplifies this paradigm—it remains to be seen whether this model of simultaneous livestreaming will remain long after the pandemic.

The Limits of Audience Engagement

The specific reach of online performances is difficult to determine. Although viewing numbers might be in the hundreds, the number of viewers watching an entire performance is small, with a sharp downturn in viewership after the first 3 minutes.Footnote23 This suggests that although overall numbers might compare favourably to a live performance, audience engagement is dramatically reduced. In the future, online performance may play a valuable role in showcasing work to a wider international audience, but live performances still have a greater impact and engagement.

The Limits of Virtual Communities

Assembled videos to create virtual choirs and virtual orchestras were a common sight early in the pandemic. These served a temporary purpose of maintaining a sense of community within these ensembles while still creating content for their audiences. However, the virtual group performance has fundamental flaws, as Anita Datta explains:

‘Virtual choir’ is, effectively, a misnomer. Technologically simulated ‘performances’ during isolation cannot synthesise place, time, affect and emotion, which are not contexts for music-making, but are revealed as integral textures in the fabric of crafting musical sound. (Datta Citation2020, 250)

These virtual choirs can never replace the act of creating music as a group, and the sophistication of in-person musical interaction. Streaming technology is improving toward the possibility of high-quality, low-latency live networked chamber performance, or even seamless hybrid live/networked performance, but that technology is still being researched and refined.Footnote24 Despite the success of ‘virtual choirs’ during 2020–2021, and of Whitacre’s pre-pandemic virtual choir, this type of choir will likely remain a novelty after the pandemic, given their many disadvantages in comparison to live choral singing.

The Future of Online Performance

If the online performances of 2020–2021 have a distinct aesthetic, and if this aesthetic has already had its day, then what is the legacy of these works? Will the experimental video techniques explored in these works find their way into concert works with film? Will experiments with liveness play a role in live works? And will DIY performances from musicians’ homes play any role in the industry?

It is too early to answer any of these questions with certainty, so I can only speak about my own plans. All My Time allowed me to experiment with film techniques that will develop in my future works with film, with further sophistication (for example, using a gyroscopic gimble attached to my body rather than a simple GoPro headset). Editing techniques using double exposure and fast montage will both remain part of my filmic repertoire. I have experimented with the relationship between live performance and video on stage in the past, and All My Time’s experiments with ambiguous or deceptive liveness, and with the blending of live and pre-recorded material on screen will no doubt play a role in future works. Finally, networked performances have huge potential for future live performances by musicians in different locations. Like All My Time, many lockdown works will not have further performances (and will garner few viewings) in the future, but their legacy will be a wider vocabulary for audio-visual experimentation and the play of virtual liveness through audio-visual media. The impact of this new vocabulary will become clear in the years to come—the most important pandemic-influenced works are yet to be written.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Zubin Kanga

Zubin Kanga is a pianist, composer, researcher and technologist. His work in recent years has focused on new models of interaction between a live musician and new technologies, including motion sensors, AI, VR, analogue synthesisers, new interactive instruments, bio-sensors, interactions with live-video, and internet-based scores. He has collaborated with many of the world’s leading composers and premiered more than 130 works. He has performed at many international festivals including the BBC Proms, Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival, Melbourne Festival, Festival Présences, Klang Festival, and November Music. He is a Lecturer in Musical Performance and Digital Arts at Royal Holloway, University of London as well as the Principal Investigator of Cyborg Soloists, a UKRI Future Leaders Fellowship project exploring new music-technology collaborations between artists and industry.

Notes

2 Perhaps paradoxically for such an internet-focused work, I did not perform WIKI-PIANO.NET online during 2020–2021, and I still feel it functions best in live performance. None of my filmed performances captures the charged atmosphere between live performer, audience, and anonymous online creators (some of whom are usually in the audience).

19 Work documentation retrieved at http://www.alexanderschubert.net/works/Genesis.php.

22 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gLQSp9YChIg. The video was uploaded to YouTube later, 23 September 2021.

23 This observation was noted and discussed by the panel members of the ‘SPARC: Looking Back and Looking Forward’ event at City, University of London, 8 June 2021. This concurs with the statistics from my own YouTube channel.

24 A current project exploring interaction between online and live musicians is the AHRC-funded project, ‘Hybrid Live: Preserving musical traditions and creating new practices performing over networks’, led by Atau Tanaka at Goldsmiths, University of London.

References

- Arts Council England. 2015. Taking Part 2014–2015: MUSIC [Industry Report]. https://www.artscouncil.org.uk/sites/default/files/download-file/Music_profile_2014_15.pdf

- Auslander, P. 2008. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Besada, J. L. 2022. “Cover, Custom, and DIY? Memetic Features in Multimedia Creative Practices.” Contemporary Music Review 41 (4). do:10.1080/07494467.2022.2087389.

- Chion, Michel. 1994. Audio-Vision: Sound on Screen. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Chiu, Remi. 2020. “Functions of Music Making Under Lockdown: A Trans-Historical Perspective Across Two Pandemics.” Frontiers in Psychology 11: 616499. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2020.616499.

- Couldry, Nick. 2004. “Liveness, ‘Reality,’ and the Mediated Habitus from Television to the Mobile Phone.” The Communication Review 7 (4): 353–361.

- Datta, Anita. 2020. “Virtual Choirs’ and the Simulation of Live Performance Under Lockdown.” Social Anthropology 28 (2): 249–250.

- Forde, Eamonn. 2020. “The Streaming Startups Trying to Save the Music Industry Mid-Pandemic.” The Guardian, 19 October. www.theguardian.com/music/2020/oct/19/streaming-startups-trying-to-save-music-industry-pandemic

- Frank, Allegra. 2020. “How ‘Quarantine Concerts’ Are Keeping Live Music Alive as Venues Remain Closed.” Vox, 8 April. www.vox.com/culture/2020/4/8/21188670/coronavirus-quarantine-virtual-concerts-livestream-instagram

- Freitas, J. 2022. “‘Make Classical Music Great Again’: Contemporary Music, Masculinity, and Virality in Memetic Media in Online Spaces.” Contemporary Music Review 41 (4). doi:10.1080/07494467.2022.2087392.

- Gopinath, Sumanth, and Jason Stanyek. 2019. “Technologies of the Musical Selfie.” In The Cambridge Companion to Music in Digital Culture, edited by Nicholas Cook, Monique M. Ingalls, and David Trippett, 89–118. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Haferkorn, Julia, Brian Kavanagh and Sam Leak. 2020. “Livestreaming Music in the UK.” [Industry Report]. https://livestreamingmusic.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/Livestreaming-Music-in-the-UK.pdf

- Hotson, Elizabeth. 2021. “Music Industry Turns to Livestreaming to Boost Revenue.” BBC, 29 July. www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-57817809

- Hunter-Timley, Ludovic. 2020. “Lockdown Launches a Stream of Live Concerts.” The Financial Times, 15 April. https://www.ft.com/content/c26e8bae-7e43-11ea-82f6-150830b3b99a

- Kanga, Zubin. 2020. “WIKI-PIANO: Examining the Crowd-Sourced Composition of Continuously Changing Internet-Based Score.” Tempo 74 (294): 6–22.

- Luck, Neil. 2020. “The Great Compression.” The Sampler, 7 April. thesampler.org/guest-editor/the-great-compression

- Onderdijk, Keley E, Freya Acar, and Edith Van Dyck. 2021. “Impact of Lockdown Measures on Joint Music Making: Playing Online and Physically Together.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: 642713. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.642713.

- Pareles, Jon. 2020. “Intimacy Is Overrated: Concerts in the Livestream Era.” The New York Times, 21 July. www.nytimes.com/2020/07/21/arts/music/livestreams-intimacy.html

- Rowley, Caitlin, and Josh Spear. 2021. “Schedule Meeting: Keeping it Live in Bastard Assignments’ Lockdown Jams.” Journal of Music, Health and Wellbeing (Autumn). https://www.musichealthandwellbeing.co.uk/musickingthroughcovid19

- Sanden, Paul. 2019. “Rethinking Liveness in the Digital Age.” In The Cambridge Companion to Music in Digital Culture, edited by Nicholas Cook, Monique M. Ingalls, and David Trippett, 178–192. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shifman, Limor. 2014. Memes in Digital Culture. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Shklovsky, Viktor. 1917 (2017). “Art as Technique.” In Literary Theory: An Anthology, 3rd ed., edited by Julie Rivkin and Michael Ryan, 8–14. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

- Tilden, Imogen. 2020. “Bittersweet Symphony: The Best Lockdown Orchestras and Choirs Online”. The Guardian, 15 April. www.theguardian.com/music/2020/apr/15/bittersweet-symphony-the-best-lockdown-orchestras-and-choirs-online

- Tomlinson, Vanessa. 2020. “84 Pianos: Pandemic Edition.” Resonate Magazine, 26 May. https://www.australianmusiccentre.com.au/article/84-pianos-pandemic-edition

- Viñuela, E. 2022. “‘What's So Funny?’: Videomemes and the Circulation of Contemporary Music in Social.” Contemporary Music Review 41 (4). doi:10.1080/07494467.2022.2087393.

- Ward, Meredith C. 2021. “The Sounds of Lockdown: Virtual Connection, Online Listening, and the Emotional Weight of COVID-19.” SoundEffects—An Interdisciplinary Journal of Sound and Sound Experience 10 (1): 7–26.

- Warnecke, Lauren. 2020. “Art and Performance During the Time of COVID-19 Lockdown.” Agenda (Durban, South Africa) 34 (3): 145–147.