Abstract

Introduction

Recent prevalence and trends of gastric/duodenal ulcer (GU/DU) and reflux esophagitis (RE) are inadequate.

Methods

We reviewed the records of consecutive 211,347 general population subjects from 1991 to 2015.

Results

During the 25 years, the prevalence of GU and DU has gradually decreased (from 3.0% to 0.3% and from 2.0% to 0.3%) whereas that of RE has markedly increased (from 2.0% to 22%). The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori (HP) infection has decreased from 49.8% (in 1996) to 31.2% (in 2010). Multivariable logistic regression analyses demonstrated that HP infection was positively associated with GU/DU and negatively associated with RE with statistical significance. The panel data analyses showed that reduced rate of HP infection is proportionally correlated with decrease of GU/DU and inversely correlated with increase of RE. It is further suggested other latent factors should be important for changed prevalence of these three acid-related diseases. Age-period-cohort analysis indicated the significant association of older age, male gender, and absence of HP infection with RE.

Conclusions

The prevalence of GU and DU has gradually decreased whereas that of RE has markedly increased in Japan. Inverse time trends of peptic ulcer and reflux esophagitis are significantly associated with reduced prevalence of HP infection.

The prevalence of gastric and duodenal ulcer has gradually decreased whereas that of reflux esophagitis has markedly increased in Japan.

The prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in Japan has greatly decreased from 49.8% to 31.2% during the 14 years (from 1996 to 2010).

Inverse time trends of peptic ulcer and reflux esophagitis are associated with reduced prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection with statistical significance.

KEY MESSAGES

Introduction

Gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis are common benign disorders which have significant relation to gastric acid [Citation1,Citation2]. The prevalence and trends of these three acid-related diseases should be paid attention to from both the clinical aspects and the economic aspects. Although there have been several recent epidemiologic studies about reflux esophagitis [Citation2–4], recent long-term observation data on peptic (gastric or duodenal) ulcer and reflux esophagitis in the general population are insufficient. Those who have acid-related diseases often have slight or no symptoms [Citation4,Citation5] and usually do not undergo upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (UGI-ES). Therefore, it is difficult to grasp the precise prevalence or trends of these benign diseases in the general population. Consequently, the recent prevalence data concerning benign acid-related diseases are not adequate today.

Generally asymptomatic people in East Asia sometimes undergo UGI-ES, because the preventive measures against gastric cancer is widely accepted especially in Japanese and Korean society [Citation6]. In this study, the recent trends of three acid-related diseases were investigated based on the data of healthy UGI-ES examinees from 1991 to 2015 in Japan. In addition, the infection status of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) was examined twice in 1996 and 2010 [Citation7,Citation8], as it is important to comprehend the rate of H. pylori infection when the trends of acid-related diseases are considered. It is established that H. pylori is the definite risk factor of peptic ulcer [Citation1,Citation5,Citation9,Citation10] and the probable preventive factor of reflux esophagitis [Citation7,Citation11–13]. Furthermore, it is also known that secretion of gastric acid is increased in relation to antrum-predominant gastritis but is reduced in relation to corpus gastritis [Citation14,Citation15]. Both types of gastritis are mostly induced by chronic infection of H. pylori; the former is more common in young people with minor atrophy of gastric mucosa whereas the latter is more common in older people with severe atrophy of gastric mucosa. By evaluating the trends of peptic ulcer and reflux esophagitis based on the longitudinal data and changed prevalence of H. pylori infection, our data clearly showed the long-time trends of three major acid-related diseases in a typical country in East Asia, where the infection rate of H. pylori has rapidly decreased.

Materials and methods

Study subjects

The medical records of consecutive 211,347 healthy general population subjects who visited our medical institute (Kameda Medical Centre Makuhari, Chiba, Japan) from 1991 to 2015 were retrospectively reviewed. The study subjects were comprised of 132,679 men and 78,668 women (51.0 ± 9.3 years old; range 20–93 years), all of whom underwent upper gastrointestinal endoscopy as part of the medical check-up. This study has been conducted in accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki and was also approved by the ethics committee of the Kameda Medical Centre (No. 17-705). All data were fully anonymized before access by the researchers.

Measurement of serum anti-H. pylori IgG

Serum anti-H. pylori IgG antibody titre of 6,452 healthy UGI-ES examinees in 1996 and 13,263 healthy UGI-ES examinees in 2010 were measured to evaluate the infection of H. pylori. We used two kits to examine the titre of serum anti-H. pylori IgG: GAP-IgG ELISA kit (Biomerica INC, California, USA) in 1996 [Citation7,Citation16] and E-plate “EIKEN” H. pylori antibody (Eiken Chemical, Tokyo, Japan) in 2010 [Citation8,Citation17]. For the former Biomerica kit, seropositivity was defined by optical density values according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For the latter E-plate Eiken kit, the titre above a cut-off value of 10 U/ml was considered as seropositivity of H. pylori. Seropositivity of both enzyme immune assay (EIA) kits was considered as the presence (positivity) of H. pylori infection.

Diagnosis of peptic ulcer and reflux esophagitis

Peptic ulcer lesions were endoscopically diagnosed according to the Sakita-Miwa classification and categorised into three stages: active, healing, and scarring stages [Citation18]. In all the analyses for peptic ulcer, active and healing stages were diagnosed as the presence of gastroduodenal ulcer. Reflux esophagitis was diagnosed according to the Los Angeles classification as like our previous report [Citation12]. All grades of reflux esophagitis (from LA-A to LA-D) were defined as the presence of reflux esophagitis. All the findings were first diagnosed by an endoscopist and rechecked by another endoscopist, and finally confirmed by the specialised conference comprised of about 20 endoscopists.

Statistical methods

All statistical analyses except for age-period-cohort analysis were performed using JMP 13.10 and SAS Universal Edition software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). In the univariate and multivariable analyses, age, sex, and the status of H. pylori infection were used as explanatory variables. In the univariate analysis, Pearson’s chi-squared test was used to analyse association with three acid-related diseases. In the multivariable logistic regression analyses, standardised coefficient and odds ratio of each variable were calculated. A two-sided p value of less than .05 was considered as statistically significant.

Concerning the panel data analyses, we used the data in 1996 and 2010 when the serum H. pylori IgG was measured. The two data in grouped format of cross-sectional study by year (1996 and 2010) were modelled as a frequency weighted regression. Since the response variable is binary, we performed a logistic regression based on a generalised linear model using count as a frequency weight. Count indicates the number of observations by pattern of response and explanatory variables.

For age-period-cohort analysis, all considerations behind the parametrizations were given in details in the Carstensen’s paper [Citation19]. In short, ages of the study subjects were classified into three groups (<44, 45–54, and 55> years old). About period, we used year 1996 and 2010, when the serum H. pylori IgG was measured. About birth cohort, six years of birth were used based on the subtraction of 41, 50, and 60 (the median of each age group) from 1996 and 2010 (years of period).

Results

Altered prevalence of H. pylori infection and three acid-related diseases in Japan

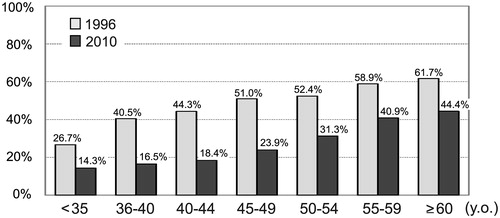

Of the 6,452 generally healthy persons in 1996, the seropositive rates of H. pylori increased from 26.7% to 61.7% with age (). Of the 13,263 generally healthy persons in 2010, the seropositive rates of H. pylori also increased from 14.3% to 44.4% with age ().

Figure 1. Rapidly changed prevalence of H. pylori infection from 1996 to 2010 in Japan. Seropositivity rates of anti-H. pylori IgG at ages <35 (20–34), 35–39, 40–44, 45–49, 50–54, 55–59, and ≥60 (60–88) years among the generally healthy persons are shown, based on the data of 6,452 subjects in 1996 and 13,263 subjects in 2010. Total numbers tested in each age group/year are in parentheses.

In all the age groups, the seropositive rates of H. pylori in 2010 were much smaller than those in 1996 (). From 1996 to 2010, the seropositive rate of H. pylori has changed from 49.8% (3,211/6,452) to 31.2% (4,136/13,263) in total. The prevalence of H. pylori infection has rapidly decreased during only 14 years in Japan.

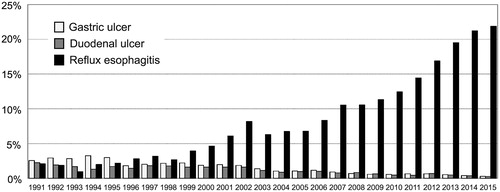

During the 25 years (from 1991 to 2015), the prevalence of peptic ulcer has gradually decreased (approximately from 3.0% to 0.3% for gastric ulcer and from 2.0% to 0.3% for duodenal ulcer, respectively) in proportion to the reduced rate of H. pylori infection (, Supplementary Table S1, Table S2). In contrast, the prevalence of reflux esophagitis has markedly increased (approximately from 2.0% to 22%) in reverse proportion to the reduced rate of H. pylori infection (, Supplementary Table S3).

Reduced rate of Helicobacter pylori infection has significantly associated with inverse increase of reflux esophagitis and proportional decrease of peptic ulcer

Using the data in 1996 and 2010, univariate analyses were performed to evaluate associations of the three acid-related diseases with age, sex, and H. pylori infection (). As for age, the prevalence of gastric ulcer tends to be higher in older people, but that of duodenal ulcer tends to be higher in younger people. For sex, the prevalence of three acid-related diseases was always higher in men compared to women. For H. pylori infection, the prevalence of peptic ulcer is much higher in H. pylori-positive persons but the prevalence of reflux esophagitis is much higher in H. pylori-negative persons.

Table 1. Univariate analyses of three acid-related diseases with age, sex, and H. pylori infection, based on the data of 6,452 generally healthy subjects in 1996 and 13,263 generally healthy subjects in 2010.

Multivariable logistic regression analyses (using the data in 1996 and 2010) were next performed (). As for age, the prevalence of gastric ulcer and reflux esophagitis tends to be higher in older people, but that of duodenal ulcer tends to be higher in younger people. However, associations of age were not so strong for all the three acid-related diseases. Concerning sex, men had higher likelihood to have gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, and reflux esophagitis compared to women with statistical significance (). Consistent with the univariate analyses, H. pylori infection showed a significant positive association with the presence of gastric ulcer (p < .0001 in 1996; p < .0001 in 2010) and duodenal ulcer (p < .0001 in 1996; p < .0001 in 2010). Contrastively, H. pylori infection showed a significant negative association with reflux esophagitis (p = .0305 in 1996; p < .0001 in 2010). Values of standardised coefficients for H. pylori in 2010 (1.033, 1.247, and –0.537) were much larger than those in 1996 (0.471, 0.552, and –0.207), suggesting that the influence of H. pylori got relatively larger during the 14 years ().

Table 2. Multivariable logistic regression analyses to evaluate associations of age, sex, and H. pylori infection with three major benign acid-related diseases using the data of 6,452 generally healthy subjects in 1996 and 13,263 generally healthy subjects in 2010.

By using age, sex, and infection status of H. pylori in 1996 and 2010 as explanatory variables, panel data analyses were additionally performed (). Concerning age, duodenal ulcer was significantly associated with younger age, which is compatible with the result of multivariable analyses (). However, apparent associations of age with gastric ulcer and reflux esophagitis could not be detected. For sex, consistent with the result of multivariable analyses, male gender is the strong risk factor for all the three acid-related diseases (). For H. pylori, the panel data analysis clearly showed that reduced rate of H. pylori infection was correlated with proportionally decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer (p < .0001) and inversely increased prevalence of reflux esophagitis (p < .0001; ). Values of coefficients accompanied with year 1996 indicate that other latent risks for peptic ulcer must be greater in 1996 than in 2010 (2.237 for gastric ulcer; 2.354 for duodenal ulcer). On the contrary, latent risk factors for reflux esophagitis must be smaller in 1996 than in 2010 (–1.965 for reflux esophagitis).

Table 3. Panel data analyses to evaluate variables using the data of 6,452 generally healthy subjects in 1996 and 13,263 generally healthy subjects in 2010.

Other latent factors than age and H. pylori infection must have played an essential role in marked increase of reflux esophagitis

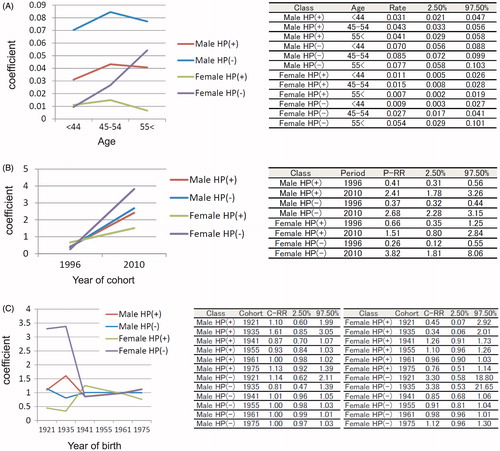

Furthermore, age-period-cohort analysis was performed to understand the time trend of reflux esophagitis by discerning three types of time-varying phenomena: age effects, period effects, and cohort effects (). Age-specific effect on reflux esophagitis indicates that older people tend to have reflux esophagitis, especially when they are male and negative for H. pylori infection (). It is also indicated that those with H. pylori infection tend to have reflux esophagitis, regardless of age or sex ().

Figure 3. Age-period-cohort analysis to evaluate the time trend of reflux esophagitis from 1996 to 2010 (A: age affect, B: period effect, C: cohort effect).

The most remarkable linear trend was observed in the period-effect (), indicating that other factors than age and H. pylori infection must have changed and played an important role in marked increase of reflux esophagitis. On the contrary, the birth cohort effect does not show clear tendency, regardless of age or H. pylori infection status of the study subjects ().

Discussion

The 25 year observation data of our medical institute clearly showed a markedly increased prevalence of reflux esophagitis and a gradually decreased prevalence of peptic ulcer in Japan (). Our result also showed that the prevalence of H. pylori infection has rapidly decreased in Japan (), which is consistent with several reports showing the similar time trend in Japan [Citation20,Citation21]. Epidemiologic changes of major benign upper gastrointestinal diseases have significantly associated with decreased rate of H. pylori infection (). Such time trends can apply to the general population subjects in many countries other than Japan, especially where rapidly decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection is observed. Even though there is some regional difference, the rate of H. pylori infection has reduced worldwide [Citation1,Citation22]. Therefore, our data can be globally useful when epidemiology of acid-related diseases is considered.

Since H. pylori infection is an established risk factor of both gastric and duodenal ulcer [Citation1,Citation5], it is understandable that decreased prevalence of H. pylori infection leads to lower prevalence of peptic ulcer. The cohort studies from China and Hongkong have reported the similar time trend of peptic ulcer and H. pylori infection [Citation23,Citation24]. Our results evidently showed that reduced infection rate of H. pylori had a strong influence on the prevalence of both gastric and duodenal ulcer. Values of coefficients in the multivariable analyses () and panel data analyses () both indicated that the status of H. pylori infection showed much stronger association with peptic ulcer than age and sex. In contrast, the prevalence of reflux esophagitis has been markedly and continuously increasing (). Though the previous cross-sectional design studies have already reported the inverse association between reflux esophagitis and H. pylori [Citation7,Citation12], our prospective observation revealed that increasing prevalence of reflux esophagitis was statistically associated with reduced prevalence of H. pylori infection. However, the influence of H. pylori infection on reflux esophagitis was not so strong as that on peptic ulcer ().

Increased values of coefficients in the multivariable analyses from 1996 to 2010 () suggested that influence of H. pylori upon peptic ulcer became relatively larger compared to age and sex. Such increased coefficient of H. pylori was also observed in the multivariable analyses for reflux esophagitis. We speculate that the effect of aging and the difference between men and women may have gotten smaller during the 14 years (from 1996 to 2010), which could lead to relatively strengthened effect of H. pylori infection.

Values of coefficients accompanied with year 1996 in the panel data analyses (2.237 and 2.354; ) indicate that latent risks for peptic ulcer got attenuated from 1996 to 2010. Though some other risks such as use of NSAIDs or low dose aspirin have become common in Japanese society [Citation25], total risk of peptic ulcer independent of age, sex, and H. pylori should have reduced during the 14 years. Of the analysed 13263 subjects in 2010, 385 regularly took NSAIDs, and among them five had peptic ulcer (1.3%) and two had duodenal ulcer (0.52%). The total disease rates of gastric and duodenal ulcer ulcer in 13263 subjects were 0.60% and 0.42%, respectively. The prevalence of peptic ulcer seems to be larger in NSAIDs users, but both were not significantly different from the total disease rates based on the statistical evaluation. Other risks such as long working hours and smoking [Citation26] have been gradually decreased in Japan, and it probably reflects the reduction of total risk of peptic ulcer. Our study population mostly consisted of working people (average: 51.0 years old) and the ratio of NSAIDs/low dose aspirin users was small in our cohort. The effect of NSAIDs/low dose aspirin may be larger in the retired aged persons.

On the contrary, the value of coefficient accompanied with year 1996 in the panel data analysis (1.965; ) indicates that latent risks for reflux esophagitis got worse from 1996 to 2010. Linearly increasing trend of coefficients of period effect in age-period-cohort analysis () also indicated that total risk of reflux esophagitis other than age, sex, and H. pylori infection has significantly increased from 1996 to 2010. To date, various risk factors including aging, genetic/racial factors, diverse lifestyles, environmental effects, etc. have been reported [Citation12,Citation27,Citation28]. Our study design could not identify such factors in detail, but the total risk of reflux esophagitis other than age, sex, and H. pylori infection has significantly increased from 1996 to 2010.

There are some limitations about our study. The first limitation is a historical cohort design, which has a potential to overlook some putative factors. We could not get the accurate information concerning the underlying disease, concomitant drugs, socio-economic background in childhood, etc. However, the panel data analyses and age-period-cohort analyses covered the weakness of multivariable logistic regression analyses to some extent. The second limitation is changed diagnostic accuracy of UGI-ES, since endoscopes used in daily clinical practice have been improved during the 25 years. The third limitation is the serum IgG-based diagnosis of H. pylori infection. Though accuracies of serum tests used in 1996 and 2010 were both more than 90% [Citation7,Citation29], additional examination like urea breath test or stool antigen test would make the evaluation of H. pylori infection more precise. The fourth limitation is the progressive spread of H. pylori eradication therapy from 1996 to 2010 in Japan. In 1996, very few of the participants had undergone eradication therapy because it was covered by national insurance in 2000 for the first time. About 5% of the subjects had already undergone eradication therapy in 2010 [Citation12]. The spread of H. pylori eradication therapy probably affected our results to some extent, because the titre of serum anti-H. pylori IgG after eradication is difficult to be predicted: some test positive for the titre of serum anti-H. pylori IgG and others test negative for it. Nevertheless, remarkable decrease of H. pylori positivity (from 49.8% to 31.2%) cannot be explained by the influence of eradication therapy.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (60.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Graham DY. History of Helicobacter pylori, duodenal ulcer, gastric ulcer and gastric cancer. World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(18):5191–5204.

- El-Serag HB, Sweet S, Winchester CC, et al. Update on the epidemiology of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Gut. 2014;63(6):871–880.

- El-Serag HB. Time trends of gastroesophageal reflux disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(1):17–26.

- Fujiwara Y, Arakawa T. Epidemiology and clinical characteristics of GERD in the Japanese population. J Gastroenterol. 2009;44(6):518–534.

- Malfertheiner P, Chan FK, McColl KE. Peptic ulcer disease. Lancet. 2009;374(9699):1449–1461.

- Leung WK, Wu MS, Kakugawa Y, et al. Screening for gastric cancer in Asia: current evidence and practice. Lancet Oncol. 2008 ;9(3):279–287.

- Yamaji Y, Mitsushima T, Ikuma H, et al. Inverse background of Helicobacter pylori antibody and pepsinogen in reflux oesophagitis compared with gastric cancer: analysis of 5732 Japanese subjects. Gut. 2001;49(3):335–340.

- Yamamichi N, Hirano C, Ichinose M, et al. Atrophic gastritis and enlarged gastric folds diagnosed by double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography are useful to predict future gastric cancer development based on the 3-year prospective observation. Gastric Cancer. 2016 ;19(3):1016–1022.

- Hentschel E, Brandstatter G, Dragosics B, et al. Effect of ranitidine and amoxicillin plus metronidazole on the eradication of Helicobacter pylori and the recurrence of duodenal ulcer. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(5):308–312.

- Graham DY, Lew GM, Klein PD, et al. Effect of treatment of Helicobacter pylori infection on the long-term recurrence of gastric or duodenal ulcer. A randomized, controlled study. Ann Intern Med. 1992;116(9):705–708.

- Potamitis GS, Axon AT. Helicobacter pylori and Nonmalignant Diseases. Helicobacter. 2015;20(Suppl 1):26–29.

- Minatsuki C, Yamamichi N, Shimamoto T, et al. Background factors of reflux esophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease: a cross-sectional study of 10,837 subjects in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e69891.

- Labenz J, Blum AL, Bayerdorffer E, et al. Curing Helicobacter pylori infection in patients with duodenal ulcer may provoke reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1997;112(5):1442–1447.

- Sonnenberg A. Review article: trials on reflux disease – the role of acid secretion and inhibition. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2004;20(Suppl 5):2–8. Discussion 38-9.

- Kandulski A, Malfertheiner P. Helicobacter pylori and gastroesophageal reflux disease. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2014;30(4):402–407.

- Watabe H, Mitsushima T, Yamaji Y, et al. Predicting the development of gastric cancer from combining Helicobacter pylori antibodies and serum pepsinogen status: a prospective endoscopic cohort study. Gut. 2005;54(6):764–768.

- Ueda J, Okuda M, Nishiyama T, et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the E-plate serum antibody test kit in detecting Helicobacter pylori infection among Japanese children. J Epidemiol. 2014;24(1):47–51.

- Miyake T, Suzaki T, Oishi M. Correlation of gastric ulcer healing features by endoscopy, stereoscopic microscopy, and histology, and a reclassification of the epithelial regenerative process. Dig Dis Sci. 1980;25(1):8–14.

- Carstensen B. Age-period-cohort models for the Lexis diagram. Stat Med. 2007;26(15):3018–3045.

- Okuda M, Osaki T, Lin Y, et al. Low prevalence and incidence of Helicobacter pylori infection in children: a population-based study in Japan. Helicobacter. 2015;20(2):133–138.

- Wang C, Nishiyama T, Kikuchi S, et al. Changing trends in the prevalence of H. pylori infection in Japan (1908-2003): a systematic review and meta-regression analysis of 170,752 individuals. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):15491.

- Nagy P, Johansson S, Molloy-Bland M. Systematic review of time trends in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infection in China and the USA. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:8.

- Jiang JX, Liu Q, Mao XY, et al. Downward trend in the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections and corresponding frequent upper gastrointestinal diseases profile changes in Southeastern China between 2003 and 2012. Springerplus. 2016;5(1):1601.

- Xia B, Xia HH, Ma CW, et al. Trends in the prevalence of peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori infection in family physician-referred uninvestigated dyspeptic patients in Hong Kong. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;22(3):243–249.

- Fujita T, Kutsumi H, Sanuki T, et al. Adherence to the preventive strategies for nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug- or low-dose aspirin-induced gastrointestinal injuries. J Gastroenterol. 2013;48(5):559–573.

- Shimamoto T, Yamamichi N, Kodashima S, et al. No association of coffee consumption with gastric ulcer, duodenal ulcer, reflux esophagitis, and non-erosive reflux disease: a cross-sectional study of 8,013 healthy subjects in Japan. PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e65996.

- Moayyedi P, Talley NJ. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Lancet. 2006;367(9528):2086–2100.

- Yamamichi N, Mochizuki S, Asada-Hirayama I, et al. Lifestyle factors affecting gastroesophageal reflux disease symptoms: a cross-sectional study of healthy 19864 adults using FSSG scores. BMC Med. 2012;10:45.

- Yamamichi N, Hirano C, Takahashi Y, et al. Comparative analysis of upper gastrointestinal endoscopy, double-contrast upper gastrointestinal barium X-ray radiography, and the titer of serum anti-Helicobacter pylori IgG focusing on the diagnosis of atrophic gastritis. Gastric Cancer. 2016;19(2):670–675.