Abstract

Background

We investigated the knowledge of COVID-19 pathogenesis and prevention, attitude, and adherence to safe clinical practices among radiographers during the pandemic and made some informed policy recommendations.

Materials and methods

The study was an online cross-sectional survey. The questionnaire captured data on respondents’ demographics, knowledge of COVID-19, attitudes, practices, and standard precaution adherence during the pandemic. Data were analysed using descriptive statistics, Pearson’s correlation and one-way ANOVA tests.

Results

Of the 255 respondents, 17.3% were actively involved in the management of COVID-19 cases. Participants had high scores regarding their knowledge of COVID-19 pathology (82.46 ± 8.67%), prevention (93.43 ± 7.11%) and attitude (74.11 ± 11.61%), but low compliance to safety precautions (56.08 ± 18.56%). Knowledge about COVID-19 prevention strategies differed significantly across educational qualifications, F(3, 251) = 4.62, p = .004. Similarly, levels of compliance with safety precautions differed across educational qualification (F[3, 251] = 4.53, p = .004) and years-in-practice (F[4, 250] = 4.17, p = .003).

Conclusion

Participants’ adherence to standard COVID-19 precautions was low. The level of professional qualification influenced participants’ knowledge and safe practices during the pandemic. Upgrading the aseptic techniques and amenities in practice settings and broadening the infectious diseases modules in the entry-level and continuous professional education may improve radiographers’ response to COVID-19 and future pandemics.

Radiographers whose qualifications were lower than a bachelor’s degree had significantly less knowledge of COVID-19 prevention.

Generally, radiographers had a positive attitude towards safe practices during the pandemic, but inadequate education, standard operational guidelines and resources affected their level of adherence.

Apart from the shortage of personal protective equipment, poor infrastructural design and inadequate hygienic facilities such as handwashing stations, running water and non-contact hand sanitizer dispensers hampered adherence to COVID-19 precautions in low-resource settings.

Key messages

Introduction

The outbreak of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) was first reported in Wuhan, China on 8 December 2019 [Citation1]. The disease spread so fast, and it was declared a global pandemic by World Health Organization (WHO) on 11 March 2020 [Citation2]. The index case of COVID-19 was reported in Nigeria on 27 February 2020 [Citation3]. As of 27 January 2023, about 266,463 people have been infected in Nigeria, including health care workers (HCWs), and 3155 deaths have been reported in 36 states and the federal capital territory [Citation4,Citation5]. The Nigeria Centre for Disease Control (NCDC) continues to report new cases of COVID-19 [Citation5]. The global easing of public health measures coupled with the emergence of highly mutated variants of the virus, such as the delta and omicron variants will put the unsuspecting HCWs at risk [Citation6].

COVID-19 patients mostly present with respiratory disorders which require a radiological investigation for diagnosis [Citation7]. Lung imaging is usually mandatory for the assessment of disease severity and to guide clinical management [Citation8]. Radiographers are health care workers who conduct radiological investigations such as lung ultrasound, computed tomography of the lungs and chest X-ray of COVID-19 patients. Radiographers come in close contact with patients during positioning, equipment manipulation, and while performing a radiological investigation [Citation9]. Their close contact with the patients exposes them to this highly contagious and infectious disease. Hence, radiographers are among the professionals at risk of health care associated infection [Citation9,Citation10]. Moreover, there was a high sociocultural-related COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy among HCWs in West Africa [Citation11–13], including radiographers in Ghana whose 40.7% were reported noncompliant with vaccination [Citation13].

The WHO and NCDC have recommended safe practices such as thorough and frequent handwashing with soap and running water, use of alcohol-based hand sanitizer, social distancing (at least 2 metres), avoiding large gatherings, covering mouth and nose with a bent elbow or tissue paper when coughing and sneezing, restraint from touching the eyes, nose and mouth and the use of facemask to minimize the spread of infections [Citation7,Citation14]. Additional safe practices for health care workers include proper use of personal protective equipment (PPE), disinfection of surfaces and fumigation of hospital premises [Citation15].

This study was grounded on a public health behavioural model – the health belief model proposes that people are most likely to take preventative action if they understand and perceive themselves to be personally susceptible to a serious health threat and the implication of risky behaviours far outweigh any benefit [Citation16]. We conceptualized that a higher COVID-19 knowledge among health care workers would lead to a better perception of the threat, positive attitudinal change, improve adherence to the safety recommendations and mitigate the transmission of COVID-19 [Citation15,Citation17,Citation18]. Disturbingly, a shortage of PPE has been reported worldwide, especially in low-resource countries such as Nigeria [Citation19]. It is uncertain whether the safety recommendations are being adhered to by the radiographers in Nigeria. Therefore, this study aimed to assess the knowledge, attitude and adherence to standard precautions among clinical radiographers in Nigeria during the COVID-19 pandemic. The main study hypothesis was that there will be no significant difference in the knowledge of COVID-19 symptomatology, knowledge of preventive measures, attitude to clinical practice and adherence to safety precautions across educational levels, years-in-practice, practice settings and regions among radiographers in Nigeria.

Materials and methods

Study design

A web-based, cross-sectional exploratory study was conducted from 13 May to 11 June 2020. This approach enabled the researchers to recruit a nationally representative sample during the second wave of the pandemic when face-to-face administration of questionnaires and access to remote areas was unfeasible. The study participants were certified radiographers in Nigeria. Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria (Reference number: NHREC/05/01/2008B-FWA0000245-1RB00002323). There are approximately 2000 registered radiographers in Nigeria, according to data from the Radiographers Registration Board of Nigeria (RRBN) [Citation10]. The post hoc sample size analysis using 255 participants showed a 5.75% margin of error and a 95% confidence interval. Our sample-to-population ratio was ≈ 1:7.84.

Instrument

The survey instrument comprised closed-ended questions. The 59-item questionnaire was divided into seven sections. Section A (nine items) asked about the most common symptoms of COVID-19, its transmission and diagnosis. Section B (five items) asked about the prevention and treatment of the disease. Section C (7 items) inquired about the respondents’ attitudes towards clinical practice during the COVID-19 pandemic. Section D (three items) asked questions about the kinds of PPE and sanitation measures needed in workplaces. Section E (six items) assessed the respondents’ adherence to standard safe practice measures. Section F (eight items) inquired about details of radiography practices during COVID-19 and whether a respondent had conducted a radiological investigation for patients with COVID-19, the type of investigation, the characteristics of such patients and their co-morbidity. Section G (13 items) obtained demographic information including years in practice, age, practice setting and sex. The instrument development involved an in-depth literature review, a focus group discussion among seven Nigerian radiographers selected through maximum variation sampling, three Delphi sessions involving a four-man expert validation panel (a professor of radiography, a chief clinical radiographer, an epidemiologist and an online survey expert) and two weeks online piloting [Citation20]. During piloting, the participants were allowed to comment on the questionnaire properties such as its length, adequacy, relevance of content and clarity of language [Citation20]. The concerns raised were addressed before the main survey. The internal consistency for sections A, B, C and E was analysed by completing Cronbach’s Alpha test on scores generated from 30 pilot-test participants, α ≥ a priori minimum value of 0.70.

Scoring of the Instrument

Each correct multiple-choice option in sections A, B and E was scored one point, corresponding to maximum scores of 25, 20 and 10, respectively, which were converted to percentages. Section C was a five-point Likert scale: strongly agreed (5), agreed (4), neutral (3), disagreed (2) and strongly disagreed (1) for positively worded questions and reverse coded for negatively worded questions. The total scores (range 7 to 35) were converted to percentages [Citation21,Citation22]. Nominal variables, sections D, F and G were not scored.

Procedures for data collection

The procedure was adopted from a previous national online survey among Nigerian physiotherapists [Citation23]. An online, web-based questionnaire was prepared using google form and made accessible using a web link. The link was emailed to the relevant radiographers’ associations in Nigeria requesting that the survey link be forwarded via their membership emailing list. The questionnaire was also posted on Nigerian radiographers’ social media platforms including WhatsApp, Twitter, and Facebook. Additionally, email was sent to practising radiographers, clinics, and diagnostic centres whose contacts were available to the authors. The purpose of the study and an informed consent form was attached to the first page of the questionnaire, including an instruction to exit the survey if the participant had answered the questionnaire in another forum. The participants either gave their consent by ticking ‘yes’ before proceeding to the questions or declined consent by ticking ‘no’ and exiting the survey. Therefore, all the participants that completed the questionnaire gave their consent. Additionally, the form was programmed to provide instant appreciation messaging to the respondent and cloud storage of data for easy accessibility and analysis.

Data analysis

Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (IBM SPSS, Version 26) was used for data analysis. We completed descriptive statistics using frequency (percentage) for nominal and categorical data. Mean ± standard deviation was used to analyse the constructs: levels of knowledge of symptoms (A), knowledge of prevention (B), attitude (C) and adherence to standard practices (E). Participants’ cumulative scores for sections A, B, C and E (continuous variables) had no missing variables or significant univariate outliers – determined by a standardized Z-score greater than ±3.29. The variables met the assumptions of linearity assessed using scatter plots, normality determined using Shapiro-Wilk test and homoscedasticity tested using Levene’s test [Citation24]. Therefore, parametric inferential statistical tests were applied. Pearson’s correlation (r) was used to test the levels of correlation among the constructs, while one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify any significant mean difference in the constructs across years-in-practice, levels of education, regions, and practice settings. The test statistics were considered significant at p ≤ .05.

Results

Demographics

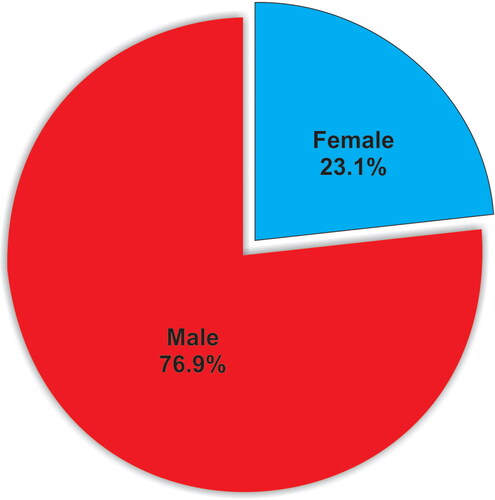

A total of 265 responses were received, however, only 255 responses were deemed complete and included in the analysis. Their sociodemographic characteristics were shown in . The radiographers were fairly distributed across the six geopolitical zones of Nigeria. They were mainly male radiographers (n = 196, 76.9%), aged between 30 and 39 years (n = 110, 43.1%), who held a Bachelor of Radiography (n = 160, 62.7%) and had practised within one decade after graduation (n = 171, 67.1%). and show the participants’ sex distribution and professional expertise, respectively. Participants were above-average in their knowledge of COVID-19 pathology (82.46 ± 8.67%), knowledge of the prevention and treatment (93.43 ± 7.11%), attitude towards clinical practice (74.11 ± 11.61%) and adherence to standard precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic (56.08 ± 18.56%). shows the participants’ attitudes towards clinical practice during the pandemic. More than half of the participants (58.5%) were willing to provide clinical services during the pandemic.

Table 1. Demographic characteristics of the survey participants (n = 255).

Table 2. Response percentage and median showing the attitude of the participants towards radiography practice during the COVID-19 pandemic (n = 255).

Knowledge of diagnosis, symptoms and transmission of COVID-19

The participants (n = 255, 100%) were aware of the COVID-19 pandemic and the pathogenic organism (n = 254, 92.9%). Most of the participants (n = 249, 97.7%) knew the accurate incubation period of COVID-19, while others thought it was longer than two weeks. Virtually all participants acknowledged that asymptomatic carriers could be infectious (n = 250, 98.0%). About half of the participants reported that Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (n = 109, 42.8%) or serology (n = 22, 8.6%) was the confirmatory test for COVID-19. However, 117 (45.9%) choose either rapid test kits, sputum culture microscopy, or temperature check. Seven (2.7%) believed there was no confirmatory test. Information on COVID-19 symptoms and SARS-CoV-2 transmission were shown in .

Table 3. Participants’ responses on COVID-19 symptoms, transmission and hospital infection (n = 255).

Knowledge of prevention and treatment of COVID-19

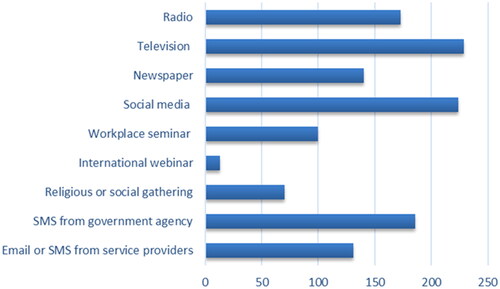

Some of these COVID-19 public health interventions were supported by the participants: laboratory screening (n = 166, 65.1%), quarantine (n = 249, 97.6%), isolation (n = 248, 97.2%), city lockdown (n = 245, 96.1%), physical distancing (n = 254, 99.6%), contact tracing (n = 245, 96.1%) and health education (n = 224, 87.8%). Other prevention strategies are shown in . Though many participants (n = 254, 98.0%) were aware of the public health agency in charge of COVID-19 responses in Nigeria, only 158 (62.0%) had the agency’s emergency response contact. The respondents’ sources of COVID-19 information are shown in .

Adherence to standard precautions in workplaces

Participants reported a paucity of PPE in their workplaces, with only 39 (15.3%) of them affirming a sufficient supply of all the required PPE. Many participants reported that the following items were insufficiently supplied at their workplaces: shoe covers (n = 138, 54.1%), goggles or face shields (n = 140, 54.9%), mouth/nose masks (n = 124, 48.6%), gloves (n = 117, 43.1%) and infectious disease gown (n = 117, 45.9%). A few participants (n = 4, 1.6%) were not supplied with any PPE at all because their employers expected them to provide it for themselves. However, materials for hand hygiene: running water, soap, sink and hand sanitizer were provided for most participants (n = 192, 75.3%). Handwashing and/or alcohol hand rub before and after procedures were among the standard recommendations. However, 29 (11.4%) of the participants did not comply, 20 (7.8%) were unsure, and the rest complied. The majority 182 (71.4%) adhered to the full recommendation of using alcohol hand rubs in addition to frequent washing of hands under running soapy water, for 20 min or more. Fifty-three radiographers (20.8%) worked in facilities without environmental disinfection practices, 136 (53.3%) practised in centres that fumigated the premises or disinfected fomites via surface cleaning, and the rest 66 (25.9%) worked in centres that did both.

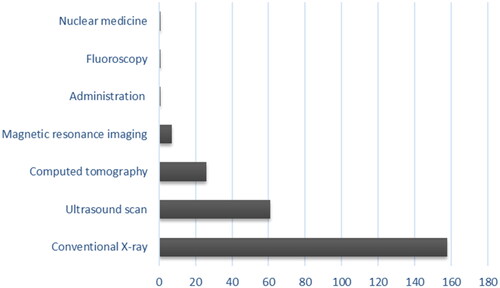

Radiography practice during COVID-19

Of the 255 participants, 96 (37.6%) worked in facilities that attended to patients with COVID-19, and 44 (17.3%) had imaged confirmed cases. Out of the 44 radiographers, 27 (61.4%) attended to COVID-19 patients brought into the radiology unit, 6 (13.6%) each imaged the patients in emergency and intensive care units, while the rest worked with stable patients in the isolation wards (n = 5, 11.4%). Two participants (4.5%) imaged COVID-19 patients who were under 15 years of age, 11 (25.0%) imaged people between 16 and 30 years, 22 (50.0%) imaged people between 31 to 45 years, 25 (56.8%) imaged people between 46 and 60 years, and others 19 (43.2%) imaged patients above 60 years of age. The comorbidities presented by the patients include diabetes, hypertensive heart disease, chronic kidney and liver diseases and prostate cancer, as was reported by 6 (13.6%) frontline radiographers. The indications for imaging received by this cohort were scans for the chest (n = 43, 97.7%), brain (n = 14, 31.8%), spine (n = 10, 22.7%) limbs (n = 9, 20.5%), vascular (n = 8, 18.2%), neurological (n = 7, 15.9) and abdominal scans (n = 1, 2.3%). Imaging modalities utilized were conventional X-ray (n = 34, 77.3%), CT (n = 17, 38.6%), ultrasound (n = 10, 22.7%), MRI (n = 2, 4.5%), fluoroscopy (n = 2, 4.5%) and ECG (n = 1, 2.3).

Inferential statistics

Results from the one-way ANOVA () showed that there was no significant difference in the participants’ knowledge of diagnosis, symptoms and transmission of COVID-19 and their attitude to safe clinical practice across years in practice, educational qualifications, practice settings and regions of practice. In terms of knowledge of preventive measures against COVID-19 (F (3, 251) = 4.62, p = .004), the Tukey post hoc test showed that participants with professional diploma qualification had significantly lower knowledge of COVID-19 prevention than their counterparts with bachelor’s degree (mean difference [M.D] = −11.59%, 95% CI: −19.77%, −3.42%, p = .002), master’s degree (M.D = −11.87%, 95% CI: −20.20%, −3.55%, p = .002) and Doctor of Philosophy (M.D = −11.42%, 95% CI: −20.47%, −2.38%, p = .007).

Table 4. ANOVA: differences in the knowledge of symptoms and preventive measures of COVID-19, attitude and safe practices across selected demographic variables.

Similarly, shows that there was a significant difference in the extent of the participants’ adherence to standard precautions during the COVID-19 pandemic across the educational qualifications (F (3, 251) = 4.53, p = .004) and years-in-practice (F (4, 250) = 4.17, p = .003). The post hoc test showed that radiographers with a Doctor of Philosophy degree adhered better to safe practice guidelines than master’s degree holders (M.D = 15.72%, 95% CI: 3.57%, 27.86%, p = .005). Those who were under the first decade of practice reported higher precautions than their counterparts within 11 to 20 years in service (M.D = 0.96%, 95% CI: 0.19%, 1.74%, p = .007), there was no significant difference between other pairs. shows that there were no significant correlations among the participants’ knowledge of pathology, prevention and treatment of COVID-19, attitude towards clinical practice and adherence to safe practices during the pandemic.

Table 5. Correlations between knowledge of symptoms and preventive measures of COVID-19, attitude and safe practices (n = 255).

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has dominated medical discourse since its onset in 2019. This study was conducted to assess the state of knowledge and preparedness of Nigerian radiographers during the peak of COVID-19 community transmission in Nigeria. Radiographers and other frontline HCWs are exposed to higher risks of contracting the disease [Citation1,Citation25]. There were concerted efforts by policymakers and agencies of government to ensure that HCWs are protected from the virus. An infected HCW can spread the infection to their colleagues, depleting the valuable human resources in the sector and predisposing uninfected health-seeking members of the community to iatrogenic and nosocomial infections. The huge negative impact of the pandemic on HCWs necessitates policy actions such as continuous professional development, entry-level radiography curriculum upgrade, installation of minimal contact aseptic devices, provision of PPEs and strategies for rapid profiling at the intake areas.

Our study revealed that the majority of radiographers are knowledgeable about the cause of COVID-19 infection, the mode of transmission and standard methods of testing such as the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) laboratory test. This outcome agrees with the findings of Ogolodom and colleagues who posited that the majority of Nigerian HCWs have knowledge of the virus [Citation17]. However, a few participants did not know the confirmatory test for COVID-19. For example, some thought that the temperature check was a confirmatory test for COVID-19. Thus, there is a need for the relevant authorities to continue COVID-19 education for HCWs through webinars, workshops, and short courses. This outcome gives credence to the need for continuous professional development for radiographers who were expected to champion the dissemination of accurate information about the symptoms, modes of transmission and prevention of the disease as HCWs.

Participants with a diploma in radiography had lower knowledge of COVID-19 prevention than their colleagues with higher qualifications. This finding is important because HCWs are critical in breaking the chain of transmission during pandemics. Health care workers are expected to play informed roles in patient care, public health enlightenment and protection of themselves to curtail the chances of nosocomial infections. Previous studies suggested that knowledge of COVID-19 symptomatology and its precautions is necessary for modifying behavioural patterns and the willingness of health care workers to perform their clinical duties [Citation17,Citation26]. Professional literacy and competence may depend on the level of educational qualification [Citation27]. Although COVID-19 is a novel disease, HCWs with a broader knowledge of infectious disease modules tend to understand the prevention strategies better. This finding was similar to the result of an international COVID-19 literacy study among physiotherapists [Citation26] and buttresses the clamour for the scrapping of diploma programmes in radiography and upgrading the entry-level benchmark to doctor of radiography programme [Citation28].

The majority of the participants had a positive attitude towards radiography practice during the pandemic. They reported their willingness to practice during the pandemic rather than staying at home. The attitudes, fears and perceptions of Nigerian health care workers in the COVID-19 pandemic have been previously reported [Citation17]. No specific study has focussed especially on radiographers who make close contact with patients during positioning, equipment manipulation and actual carrying out of required investigations.

Nonetheless, the lack of adequate PPE remains a huge global challenge, due to shortages in supply and rising demand globally [Citation19]. Consequently, only 15.3% of participants had a complete supply of PPEs. Moreover, the majority of participants worked in settings that lacked basic aseptic amenities such as installed wash-hand basins, running tap water, disinfectant equipment, and consumables. The perceived inadequacy of preventive measures in the face of the relaxing government’s public health policy has heightened the fears of contracting the disease among HCWs [Citation17]. Similarly, Refeai and colleagues reported that despite the inadequate provision of PPE to the HCWs in Egypt, they showed a positive attitude towards practice during infectious disease outbreaks [Citation18]. Priority should be given to the hospital settings while distributing scarce infectious diseases intervention resources; the regulatory agencies should ensure that clinics meet basic amenities and procedural requirements.

Our study showed that Nigerian radiographers engaged in the management of COVID-19-infected patients in their practice settings. It has been established that medical imaging plays a vital role in confirming the diagnosis in clinically suspected cases [Citation29] and the treatment of COVID-19 patients [Citation7]. Imaging helps in the differential diagnosis between COVID-19 and other viral respiratory illnesses which may present with similar symptoms [Citation30]. Our study participants reported that the majority of referrals were for chest imaging, of which chest radiography and CT were the most common. On a few occasions, lung ultrasound and MRI were requested. This supports the previous literature that chest radiography, chest CT, lung ultrasound and MRI were common imaging modalities in the evaluation of COVID-19 patients [Citation31–33].

Radiographers in Nigeria were expected to adhere to the WHO and NCDC recommended safe practices to curtail COVID-19 transmission. Notwithstanding, we found that the participants’ adherence to standard COVID-19 precautions were low. The post hoc analysis showed that radiographers with higher educational qualifications and years of practice adhered better to the safe practice guidelines. Radiographers with higher qualifications and clinical experiences may have acquired more knowledge and skills for practice in the infectious disease era [Citation34]. These findings suggest the need for the incorporation of safe practice guidelines against infectious diseases into radiography entry-level education and continuous professional development. Emphasis should be laid on competence with the use of PPE including techniques for donning and doffing the PPE. Barratt and colleagues reported that HCWs’ competence and familiarity with PPE were suboptimal during COVID-19 and recommended PPE training programmes [Citation15].

A major thrust of this study is to assess the impact of education, years of experience, region and practice setting on the knowledge and attitude of radiographers towards COVID-19 and their adherence to safe practice protocols. Our study showed no significant influence of the region and practice settings on the set parameters. However, it was noted that radiographers with higher educational qualifications and more years of practice showed a better understanding of prevention strategies and adhered better to standard precautions. The importance of this finding is that public health education is necessary and effective in creating awareness of the pandemic. However, improving prevention strategies and the capacity of radiographers to continuously discharge their duties without endangering themselves or patients will require further professional training [Citation25]. Since radiographers’ level of training and scope of practice, infrastructural design and installed equipment differs across countries and practice settings, low-resource countries may be at higher risk of nosocomial and iatrogenic infections [Citation35]. It is therefore necessary that national policies are tailored to bridge these gaps [Citation9,Citation28,Citation35].

There is no doubt that the practice settings, as well as radiographers’ responsibilities and expectations, have changed in the face of the pandemic. As noted by Akudjedu and colleagues, the pandemic has created a working environment, full of uncertainty and unexpected changes in organizational protocols and schedules [Citation36]. The associated increase in work-related stress may require a better coping strategy. Previous studies showed that epidemics can lead to the development of new or worsening psychiatric symptoms such as fear, anxiety, panic attacks and depression among HCWs [Citation37]. Adequate provision of PPEs and improved infrastructure in hospitals and practice settings will motivate radiographers to practise during COVID-19 and future pandemics. Therefore, we recommend a consistent public health campaign to encourage and sustain knowledge about the evolving variants of coronavirus among radiographers, through continuous training on the aspects of prevention and adherence to established safety protocols. In the long term, these experiences should be incorporated into curriculum updates.

Limitation

The use of the non-probability sampling method could limit the generalizability of the results of this study due to the lack of randomization and the potential for nonresponse bias. Moreover, similar to most questionnaire-based studies, the authors cannot vouch for the veracity of the responses. In this case, there could be potential for social desirability bias when radiographers were asked about their adherence to COVID-19 standard precautions in workplaces.

Conclusion

Nigerian radiographers had good knowledge of COVID-19 symptoms, transmission, and prevention. They also had a positive attitude towards clinical practice during the pandemic. However, adherence to standard precautions was low. Reported barriers against safe clinical practices include scarcity of PPE and poor sanitary installations in workplaces. Moreover, the level of education was observed to influence participants’ knowledge of COVID-19 pathology and their adherence to standard precautions. Further training on infectious diseases and an adequate supply of PPE could improve the overall public health response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Ethical approval

The authors obtained ethical approval from the Health Research and Ethics Committee of the University of Nigeria Teaching Hospital, Enugu, Nigeria (Reference number: NHREC/05/01/2008B-FWA0000245-1RB00002323).

Consent form

The objectives of the study were clearly explained to each participant who then signed an informed consent form.

Authors’ contributions

C.I.E., O.F.E. and O.K.O contributed to the conception of this study. C.I.E., O.F.E., C.J.A., A.W.I., C.N.A., A.A.A. and O.K.O made substantial contributions to the design, acquisition of data and performed the statistical analysis. O.F.E., C.J.A., C.N.A., A.A.A. and O.K.O. were responsible for drafting the article. C.I.E., O.F.E. and A.W.I. contributed to its critical revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript for publication.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge all the COVID-19 frontline Nigerian radiographers who participated in the study.

Data availability statement

The questionnaire used and datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request. Our institution’s ethics guidelines warrant that the primary investigator holds primary data for at least five years before making it publicly available.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Li Q, Guan X, Wu P, et al. Early transmission dynamics in Wuhan, China, of novel Coronavirus-Infected pneumonia. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(13):1–11.

- Cucinotta D, Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Biomed. 2020;91(1):157–160.

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. Coronavirus disease (Covid-19) frequently asked questions; 2020 [accessed 2021 Mar 4]. Available from: https://ncdc.gov.ng/themes/common/docs/protocols/173_1583156673.pdf

- World Health Organization Nigeria - WHO Coronavirus (COVID-19) dashboard; 2021 [accessed 2023 Jan 27]. Available from: https://covid19.who.int/region/afro/country/ng

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. COVID-19 Nigeria; 2022 [accessed 2022 Aug 18]. Available from: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/

- Hewins B, Rahman M, Bermejo-Martin JF, et al. Alpha, beta, delta, omicron, and SARS-Cov-2 breakthrough cases: defining immunological mechanisms for vaccine waning and vaccine-variant mismatch. Front Virol. 2022;2:849936.

- Adhikari SP, Meng S, Wu YJ, et al. Epidemiology, causes, clinical manifestation and diagnosis, prevention and control of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) during the early outbreak period: a scoping review. Infect Dis Poverty. 2020;9(1):29.

- Mongodi S, Orlando A, Arisi E, et al. Lung ultrasound in patients with acute respiratory failure reduces conventional imaging and health care provider exposure to COVID-19. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2020;46(8):2090–2093.

- Okeji MC, Ugwuanyi DC, Adejoh T. Radiographers’ willingness to work in rural and underserved areas in Nigeria: a survey of final year radiography students. J Radiogr Radiat Sci. 2014;28(1):6–10.

- Adejoh T. An inquest into the quests and conquests of the radiography profession in Nigeria. J Radiogr Radiat Sci. 2019;33(1):1–38.

- Adejumo OA, Ogundele OA, Madubuko CR, et al. Perceptions of the COVID-19 vaccine and willingness to receive vaccination among health workers in Nigeria. Osong Public Health Res Perspect. 2021;12(4):236–243.

- Gbeasor-Komlanvi FA, Afanvi KA, Konu YR, et al. Prevalence and factors associated with COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in health professionals in Togo, 2021. Public Health Pract. 2021;2:100220.

- Botwe BO, Antwi WK, Adusei JA, et al. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy concerns: findings from a Ghana clinical radiography workforce survey. Radiography. 2022;28(2):537–544.

- Nigeria Centre for Disease Control. Public health advisory on Covid-19; 2020 [accessed 2021 Mar 04]. Available from: https://covid19.ncdc.gov.ng/advisory/

- Barratt R, Shaban RZ, Gilbert GL. Characteristics of personal protective equipment training programs in Australia and New Zealand hospitals: a survey. Infect Dis Health. 2020;25(4):253–261.

- Hayden J. Introduction to health behavior theory. Massachusetts, USA: Jones & Bartlett Learning; 2022.

- Ogolodom MP, Mbaba AN, Alazigha N, et al. Knowledge, attitudes and fears of healthcare workers towards the corona virus disease (COVID-19) pandemic in South-South Nigeria. Health Sci J. 2020;1:002.

- Refeai SA, Kamal NN, Ghazawy ERA, et al. Perception and barriers regarding infection control measures among healthcare workers in Minia City. Int J Prev Med. 2020;11:11.

- World Health Organization. Shortage of personal protective equipment endangering health workers worldwide; 2020 [accessed 2021 Mar 04]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/03-03-2020-shortage-of-personal-protective-equipment-endangering-health-workers-worldwide

- Onyeso OKK, Umunnah JO, Ibikunle PO, et al. Physiotherapist’s musculoskeletal imaging profiling questionnaire: development, validation and pilot testing. S Afr J Physiother. 2019;75(1):1338.

- Batterton KA, Hale KN. The Likert scale what it is and how to use it. Phalanx. 2017;50(2):32–39.

- Sullivan GM, Artino ARJr. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert-type scales. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(4):541–542.

- Onyeso OK, Umunnah JO, Eze JC, et al. Musculoskeletal imaging authority, levels of training, attitude, competence, and utilisation among clinical physiotherapists in Nigeria: a cross-sectional survey. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):701.

- Garson GD. Testing statistical assumptions. Asheboro (NC): Statistical Associates Publishing; 2012.

- Ogolodom MP, Mbada AN, Nwodo VK, et al. The impact of covid-19 pandemic on academic and professional development programmes organized by the radiographers registration board of Nigeria. J Biomed Sci. 2021;10(1):1–6.

- Ezema CI, Onyeso OK, Okafor UA, et al. Knowledge, attitude and adherence to standard precautions among frontline clinical physiotherapists during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey. Eur J Physiother. 2023;25(3):138–148.

- Massing N, Schneider SL. Degrees of competency: the relationship between educational qualifications and adult skills across countries. Large-Scale Assess Educ. 2017;5(1).

- Maduka BU, Ugwu AC, Adirika BN. Perception of radiography lecturers towards the proposed doctor of radiography program. Egypt J Radiol Nucl Med. 2021;52(1):106.

- Adejoh T, Onwuzu SWI, Luntsi G, et al. X-ray special investigations rebook analysis (XSIRA). IOSR J Dent Med Sci. 2015;14(7):71–75.

- Stogiannos N, Fotopoulos D, Woznitza N, et al. COVID-19 in the radiology department: what radiographers need to know. Radiography. 2020;26(3):254–263.

- Revel MP, Parkar AP, Prosch H, et al. COVID-19 patients and the radiology department-advice from the. Eur Radiol. 2020;30(9):4903–4909.

- Yang W, Sirajuddin A, Zhang X, et al. The role of imaging in 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia (COVID-19). Eur Radiol. 2020;30(9):4874–4882.

- Dai W, Zhang H, Yu J, et al. CT imaging and differential diagnosis of COVID-19. Can Assoc Radiol J. 2020;71(2):195–200.

- Desta M, Ayenew T, Sitotaw N, et al. Knowledge, practice and associated factors of infection prevention among healthcare workers in Debre Markos Referral Hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. BMC Health Serv Res. 2018;18(1):465.

- Akudjedu TN, Mishio NA, Elshami W, et al. The global impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on clinical radiography practice: a systematic literature review and recommendations for future services planning. Radiography. 2021;27(4):1219–1226.

- Akudjedu TN, Lawal O, Sharma M, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on radiography practice: findings from a UK radiography workforce survey. BJR Open. 2020;2(1):20200023.

- Montemurro N. The emotional impact of COVID-19: from medical staff to common people. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;87:23–24.